To Mrs. —–.

In my discussion of Hester Mulso’s coterie fame in Chapter 1, I suggested that the penetration of this fame into the print medium could not occur until Mulso, as Mrs. Chapone, became part of a more egalitarian coterie – that of Elizabeth Montagu. This transition, however, did not occur until the 1760s, leading directly to Chapone’s widely disseminated print publications of the 1770s – a process I will trace to its completion in Chapter 3. At the time of Mulso’s initial coterie fame, Montagu’s circle did not yet exist, let alone showing any sign of the cultural influence it achieved in the subsequent decades. At the start of the 1750s, the Yorke circle and those of the elderly Duchess of Somerset at Percy Lodge, whom Catherine Talbot visited at this time, and of Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, the Duchess of Portland at Bulstrode,2 seem to have been the strongest centers of gravity for persons of letters who were members of the elite and gentry. Like members of the Yorke circle who also came into Richardson’s orbit, friends of the Duchess of Portland overlapped with the North End coterie discussed in Chapter 1. In particular, Mary Granville Pendarves (after 1743 Mrs. Delany, wife of the Irish clergyman Patrick Delany) and Anne Donnellan, two of the Duchess’s closest connections, were Richardson’s visitors and correspondents during the period of Sir Charles Grandison’s composition. As a young woman, Elizabeth Robinson, later Montagu, had been an intimate friend and companion of the Duchess, who was five years her senior, but after Elizabeth’s marriage in 1742 the relationship cooled. Thus, the correspondence with the Duchess of Portland falls off significantly in this decade, replaced by letters to and from Montagu’s husband Edward, her cousin Gilbert West, and through him, George Lyttelton. And it was not through Bulstrode adherents and their connections to Richardson that Montagu encountered Carter but through the print manifestation of the latter’s connection to Talbot – her translation of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus.

The aim of this chapter is to trace the coalescence and emergence into cultural prominence in the latter half of the 1750s of a literary coterie centered on Elizabeth Montagu. While this coterie formed part of the extended network that has become commonly known as “the Bluestockings,” the term can be slippery in its reference, initially being used loosely to refer to small, mixed-gender conversational evenings, then expanding to indicate the larger assemblies of “beaux esprits” hosted by Montagu, Frances Boscawen, Hester Chapone, and others – but particularly Elizabeth Vesey, in her “Blue room” in Clarges Street. The gendering of the label in the late 1770s and beyond has had a backward-reaching influence as well, so that its use is as likely to invoke the dozen or more intellectual women of the mid- to late eighteenth century who represent two generations of remarkable accomplishments in the arts, but who are connected in a much looser network than that of the small circle I explore here.3 This chapter will thus use “the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie” to designate the intimate network of Elizabeth Montagu between about 1758 and 1773, beginning soon after the death of Gilbert West with the growing friendship of Montagu and George Lyttelton (Sir George from 1751, 1st Baron Frankley from 1756), and ending with the latter’s death. I will focus chronologically on the movements of Carter and Montagu toward the formation of the group; its first, intensely productive period which saw both manuscript jeux d’esprits and the publication of Lyttelton’s 1759 Dialogues of the Dead, to which Montagu contributed three dialogs, and Carter’s Reference Carter1762 Poems on Several Occasions; and a second period of productivity with Montagu’s 1769 Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear and Lyttelton’s history of Henry II (1767–71). Throughout, my interest is in the characteristics and conditions that produced its range of literary expression and engagement as a coterie balanced between the interpenetrating scribal and print-based media systems of the time. I will then look at the literary projects initiated by the group, with a special focus on its role in the career of Hester Mulso Chapone.

I will also discuss, by contrast, the complicated position of Catherine Talbot who, despite her widely recognized literary talent, her friendships with Carter and Montagu, and her central role in furthering Carter’s fame, never became fully engaged with the newly formed Montagu–Lyttelton circle. If Talbot’s situation is thus a foil, setting in relief the contextual and motivational dynamics involved in the formation of a coterie, Samuel Johnson’s career path in the 1750s plays a shadow role in this chapter in that his articulation of the terms of reference for professional authorship came to the fore as Talbot, Carter, and other members of Richardson’s circle attempted to patronize The Rambler. This encounter between the values and practices of the print author in juxtaposition to those of the manuscript-exchanging coterie can be seen as prefiguring the terms of the ultimate rupture between Johnson and adherents to coterie values – particularly Montagu and then-Lord Hardwicke, Philip Yorke – in the 1780s (see Chapter 5). In its ensemble, this chapter traces from the perspective of media choice the formation of one branch of the group that has become known to literary history as the Bluestocking circle, while demonstrating the ways in which individuals might adopt an approach to media modes and practices that served their unique ends.

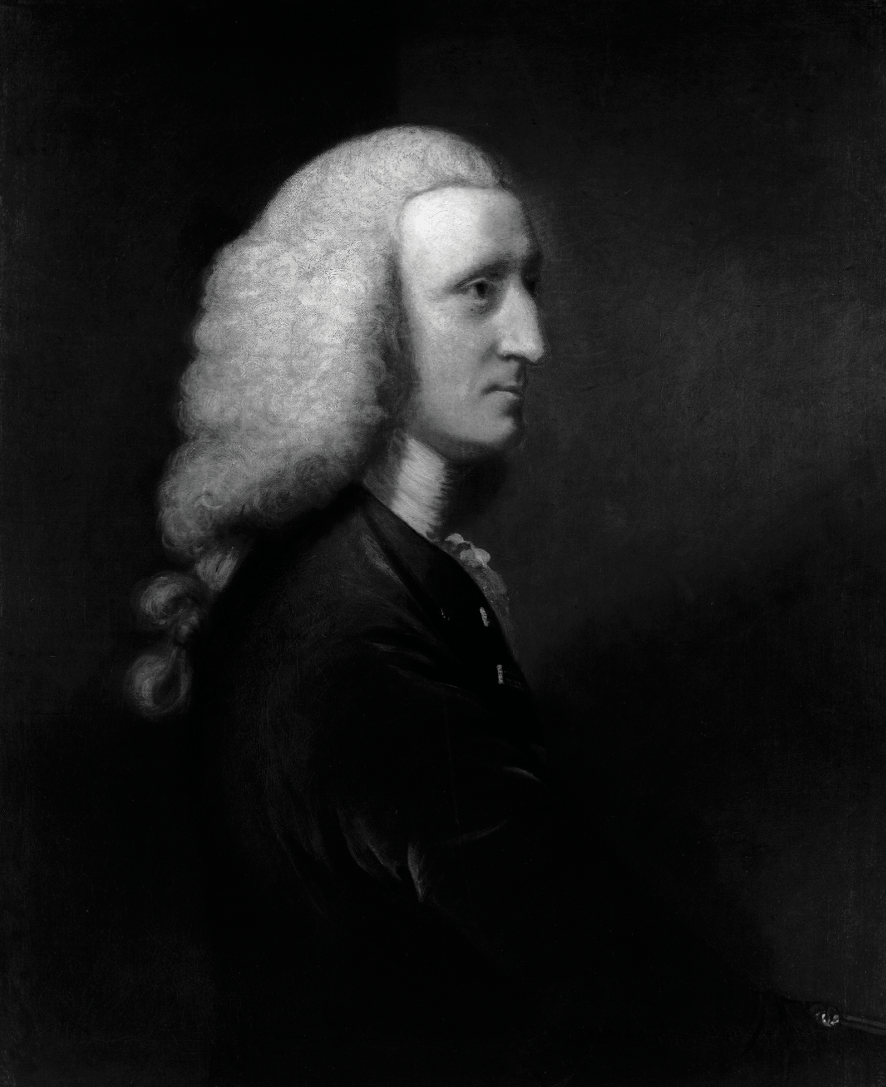

The core members of the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie were linked by intense friendships, as the number and contents of letters exchanged by Montagu with Lyttelton, Carter, and William Pulteney, Earl of Bath, attest. But while Montagu also maintained an active correspondence during this period with her husband, her sister Sarah Scott, and other women friends such as Boscawen and Vesey, the network ties of the Montagu–Lyttelton group stand out as being founded to a significant degree on mutual encouragement and admiration of literary talents – Montagu’s epistolary skills, Lyttelton’s writings in poetry and prose, both past and in progress, Carter’s learned and morally improving Epictetus and poems, and even Bath’s witty conversation and occasional epistolary flourishes – which crossed lines of gender, economic status, and, to an extent, political affiliation. This network was dense, with direct social ties between each of Montagu, Bath, and Carter, who would often see each other multiple times in a day when in London, and spent periods of time together at Tunbridge Wells; Lyttelton, by virtue of his extensive family circle, his building and landscaping projects at Hagley, and the pressing concerns of his young children in these years, was often based at his Hagley estate and connected to the group primarily through correspondence with Montagu, when they were not both in residence in their Hill Street homes in London.4 (The doctor Messenger Monsey and the philosopher and naturalist Benjamin Stillingfleet were directly connected with this coterie, but there is a clear difference in the continuity and closeness of the ties. Elizabeth Vesey, after 1761, became an increasingly important connection for Montagu, Lyttelton, and Carter; while she played an important role in the coterie’s adoption of Ossianic tastes and practices, her primary interests and talents seem to have been social and conversational, rather than literary.) Two portraits known to link members of the group in this period – one of Carter, painted by Katherine Read and owned by Montagu (Figure 2.1), and another of Montagu, by Allan Ramsay and possibly for presentation to Bath, who took an active interest in its production – convey in their openness and informality the sense of mutual trust, intellectual engagement, and lively intimacy between members of the group; a third, informal portrait of Lyttelton, tentatively dated 1756, likely arises out of a similarly sociable context (Figure 2.2).5

Figure 2.1 Katherine Read, Elizabeth Carter, c. 1765.

Figure 2.2 Artist unknown, George Lyttelton, 1st Baron Lyttelton, c. 1756.

Like the Yorke–Grey and Richardson coteries discussed in Chapter 1, the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie used scribal production and circulation to seal its group identity; its epistolary exchanges also record critical discussion of events in the world of letters (both transnational and local), the initiation and development of its print publishing projects, the patronage of other writers, and, not incidentally, the hope of influencing the national political sphere through all of these activities.6 The particular character of this group, not only in relation to such print-oriented professionals as Samuel Johnson, but also within the larger “Bluestocking” phenomenon, throws into relief how mid-century individuals might fashion a balance between media modes and practices that served their unique purposes. Thus, the Montagu–Lyttelton circle took advantage of the interpenetrating scribal and print-based media systems of the 1750s and 1760s to pursue its goals of self-improvement, of increasing the fame of the deserving, and of directing contemporary society, particularly literary culture, toward the ends of individual moral and intellectual improvement and collective British advancement.

Elizabeth Carter becomes a coterie author: criticism, patronage, and Johnson’s The Rambler

I have already suggested, in Chapter 1, Elizabeth Carter’s reluctance to be drawn into the tight orbit of Samuel Richardson in the early 1750s. As noted, the relationship had begun badly when Richardson broke the rule of respecting a scribal author’s wishes regarding publicity, inserting the anonymous “Ode to Wisdom,” as “by a lady,” into his Clarissa. The transgression illustrates the common fate of a manuscript poem once copies circulated beyond the author’s control; as Richardson explained, it had been impossible to seek permission because his inquiries could not identify the author. It was Talbot who informed Carter of the print appearance of her poem, with which she was obviously familiar through scribal channels, and the mediator in the case was Susanna Highmore. Richardson went on to ask Highmore in 1750 to seek permission from Carter to print the ode in its entirety in the third edition of his novel. Carter replies, “When you write to Mr. Richardson I beg you will be so good to make my Compliments to him. the ode is intirely at his Service.”7

It was in this scribal context that Carter developed her sense of the potential of the epistolary form. In a detailed and nuanced discussion of Carter’s career that in many respects parallels and elaborates my overview here, Melanie Bigold has shown how Carter self-consciously pursued a hybrid model of patronage and collaboration based on scribal practices, on the one hand, and a selective use of print to intellectually and morally exemplary ends, on the other, concluding that “adherence to manuscript exchange and exemplarity was not, in artistic, intellectual, or moral terms, a constraining mode of practice” for Carter. While Bigold emphasizes a lifelong pattern of cultivating contacts with persons of letters, I will show here specifically how Carter developed coterie relationships in the 1740s with Talbot, Highmore, and Mulso especially, leading to the establishment of her position as a central member of the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie. Already a well-published and applauded print author by the end of the 1730s, through her work for the Gentleman’s Magazine and her translations of French and Italian treatises, she was slower to exploit the possibilities of the literary coterie. Her earliest letters, chiefly to close female friends in Kent or to Edward Cave in London, are brief and functional, alternating between the gossipy chat required to maintain the bonds of a close-knit Deal community (updates on the expectations of dress in London and apologies that Crousaz, whom Carter had translated, “is too metaphysical for you”) in the one case, and the necessary business of carrying on relations in the London world of letters in the other (requests that recent publications be shipped to her, messages for fellow writers, the search for “a red short Cloak” left behind somewhere).8 Through the 1740s and early 1750s, however, her correspondence with Talbot, first, and then Highmore and Mulso drew out her developing critical voice and encouraged a sense of her potential for cultural influence as an acknowledged and accomplished woman of letters.

The Talbot–Carter correspondence interweaves exploration of moral questions related to the practice of everyday life with discussion of a very wide range of reading, from Akenside to Young in English alongside French, Italian, and classical authors on philosophy, education, and literature. Carter and Highmore carried on their own literary exchange from at least 1748, when the former writes to thank her friend “for the charming [odes] you were so good to send me.” Highmore’s letters to Carter accomplish other coterie functions: they propose subjects of critical discussion and/or translation (such as the works of Charlotte Lennox, Sarah Fielding, Metastasio, Boileau, and Horace) and they publicize the upcoming subscription edition of Mary Leapor’s poems, organized by Isaac Hawkins Brown and Richardson. In the latter case, Carter politely declines to write a “vouching” poem for the volume, protesting, “Indeed Dear Miss Highmore you pay me much too great a Compliment in supposing me capable of writing upon any Subject that is proposed to me” and insisting that “her [Leapor’s] memory will be celebrated by so many others who are capable of doing it a much greater Honour”; she does, however, ask Highmore to send her the subscription proposal, implying that she will promote the project among her acquaintance.9 In the case of Mulso, as shown in Chapter 1 and elaborated below, Carter served as a valuable older female friend, but presumably also gained the stimulation of engaging with a sharp wit and the confidence of standing in the position of an authority figure. Thus, through her association with members of Richardson’s coterie, Carter found new opportunities for sociable literary criticism and patronage, key activities she would be involved in as a member of Montagu’s circle.

One significant opportunity for these female correspondents to put their cultural resources into action was the patronage of Samuel Johnson’s periodical The Rambler. While working on his Dictionary project, Johnson published the periodical anonymously; it appeared twice weekly, beginning in March of 1750, for a total of 208 issues. The Rambler did not sell as well as hoped in its periodical format, ceasing publication after two years, but it was almost immediately reissued in a six-volume collected edition and remained popular throughout the century. In its collected form, demand for The Rambler was immediate, steady, and widespread; there were nine London “editions” by the time of Johnson’s death in 1784. Paul Korshin suggests that we have here the deliberate construction of a classic – that the goal from the start was to “create a following and, through publication in a collected version, widen an author’s reputation.” The Rambler persona himself articulates in his earliest essays a desire to circumvent “the difficulty of the first address on any new occasion” in preference for “the honours to be paid him, when envy is extinct, and faction forgotten, and those, whom partiality now suffers to obscure him, shall have given way to other triflers of as short duration as themselves.” For this reason he will seek the favorable regard of “Time,” who “passes his sentence at leisure.”10

As Johnson’s references to “faction” and “partiality” hint, this choice of orientation toward a future audience can be read as a decision against seeking coterie patronage. It is useful to recall that for the mid-century London author by trade, there were two, usually intersecting, routes of possible escape from a hand-to-mouth existence: one was to produce works whose built-in durability would make them profitable investments for booksellers, and for which, therefore, immediate copy payment and potential further remuneration could be substantial. The other was to find subscribers, generous patrons, and even long-term posts or pensions in a patronage system. This system persisted, as my discussion of the Yorke–Grey circle has demonstrated, in the personal relations fostered by the coterie; indeed, Dustin Griffin shows in his 1995 study Literary Patronage in England, 1650–1800 that it was evolving to meet new and ongoing cultural needs of authors and those who supported, and wished to be known to support, British letters.

From the perspective of such would-be patrons, Johnson’s choice against such support seems to have been incomprehensible. Foremost among these scribal commentators are Highmore, Talbot, and Carter; in attempting to create a readership for The Rambler by talking it up and writing about it, these individuals were taking upon themselves the role of patronage brokers – advising the author and seeking to widen the circle of the periodical’s advocates and audience. The socially superior Talbot’s careful channelling of advice through Carter as a former London colleague of Johnson’s shows their self-consciousness not only about the role they were playing but also about the complicated blend of social inequality and emerging professional pride that could make it difficult for an author to straddle the line between the two systems; she writes, “He ought to be cautioned … not to use over many hard words. This must be said with great care … Any hint that is known to come from you will have great weight with the Rambler, if I guess him right, particularly given in that delicate manner you so well understand.” Carter even seems to have had vague hopes of some sort of pension for Johnson, a hope she articulates in its disappointment, in response to Mr. Rambler’s farewell: “For some minutes it put me a good deal out of humour with the world, and more particularly with the great and powerful part of it … In mere speculation it seems mighty absurd that those who govern states and call themselves politicians, should not eagerly decree laurels, and statues, and public support to a genius who contributes all in his power to make them the rulers of reasonable creatures.”11

Ultimately, Carter’s and Talbot’s letters reveal their frustration at the paper’s failure to construct a sociable author–reader relationship. Despite their best efforts on both the producing and the receiving ends, the author stubbornly refused to cater to the tastes of worldly contemporary readers, and readers refused to be told what they should like. A letter from Jemima Grey indicates that Talbot’s advocacy for the periodical targeted members of the Yorke–Grey coterie; on June 28, 1750, Grey writes from Wrest, “Look-ye, my dear Miss T—t, if you really are the Writer of the Rambler, or if any particular Friend of Yours is an Assistant, (& without one of these I can’t guess how you should be so well acquainted with the Author’s Thoughts or Designs) You should have given me a Hint that I might be more cautious in my Remarks upon it. But as it is too late now, & I have already done as bad as I can do, I must e’en plunge on, & support the Sentence given at this Place.” Grey’s comment makes it clear that the arguments fell on deaf ears, and Talbot finds herself writing a post-mortem for the periodical to Carter:

I assure you I grieved for [the death of that excellent person the Rambler] most sincerely, and could have dropt a tear over his two concluding papers, if he had not in one or two places of the last commended himself too much; … Indeed `tis a sad thing that such a paper should have met with discouragement from wise, and learned, and good people too – Many are the disputes it has cost me, and not once did I come off triumphant.

Carter commiserates in reply, “It must be confessed … that you shewed an heroic spirit in defending his cause against such formidable enemies even in London. Many a battle have I too fought for him in the country but with very little success.”12

What The Rambler’s first and friendliest readers were observing, then, was Johnson’s deliberate rejection of one media culture’s modes of relation in favor of another’s. Chapter 3 will demonstrate that Carter (and the Montagu and Shenstone coteries in general) did understand the appeal of the potentially transhistorical and disembodied audience offered by print. But as a committed practitioner of social authorship, Carter did not share Johnson’s view that the model of reader-as-patron should, or even could, be circumvented, and for the early 1750s she was right. Pensions aside, the publishing world of mid-century London remained one dependent upon recommendations, whether through personal contacts within the trade or through an overlap of commercial and patronage networks; the very determination with which Talbot, Carter, and others pursued their goal of influencing both The Rambler papers and their reception affirms the potentially decisive role of social interactions in determining the “reach” of an author in this hybrid, geographically centralized literary culture.13 Yet the contest over The Rambler’s immediate reception stands as a moment of differentiation, in which the social embeddedness of periodical writing as continuous with oral and manuscript communication was at odds with the increasing generalization of context into which print was moving with the rapid expansion of readerships and distribution networks.

If the debate over Johnson’s Rambler put pressure on the bonds holding scribal and print-trade practices together, Elizabeth Carter’s major literary project of the 1750s, her translation of the writings of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus from the Greek, demonstrated how well the system could work. The translation originated in 1748 as a personal project requested by Talbot (apparently to assist her in dealing with her grief over the death of Secker’s wife Catherine early in that year) and supported by the scholarly expertise of Thomas Secker; over the first five years of its gestation, the Carter–Talbot correspondence records the steady encouragement, even pressure, brought to bear on Carter by Talbot and by Secker through Talbot, as the translation competed with Carter’s duties of educating her brother and keeping house for her father’s family. In this sense, the work arose out of the mutually nurturing sociability of the coterie without the need of print publication to justify it. Yet the print medium offered itself as the best means to fulfill the project’s goal as expressed from the beginning in discussions between these three individuals: to capture Stoic philosophy in a manner that would speak forcefully to contemporary readers. To maximize the potential impact of the translation, Secker urges Carter to adopt a plainspoken style that will not only accurately represent the original but also “be more attended to and felt, and consequently give more pleasure, as well as do more good, than any thing sprucer.”14

In convincing Carter to do public good by harnessing the power of print, her friends were simultaneously harnessing the power of their social connections to support the project. Secker used his contacts to ensure that no rival translation was in the offing, mediated consultations with the classicist James Harris about difficulties in the Greek, and debated with Talbot and Carter how best to adjust the tone and contents of the textual apparatus. As Carter writes of the discussions with Harris, “This has made the scheme public, however; and so this poor foolish translation, if it ever does appear, instead of the comfort of sneaking quietly through the world, and being read by nobody, will be ushered into full view, and stared quite out of countenance.” While Talbot graciously declined having her name printed as dedicatee (“Your inscription I would have you consider as already made, and in manuscript thankfully accepted; nor can I ever forget the goodness you have had in undertaking on my idle request so laborious a work. But further than this your request cannot possibly be granted”), the published work was fittingly prefaced with a commendatory ode by Carter’s coterie friend Mulso. The initial subscription of 1031 names – according to Carter’s nephew and memoirist Montagu Pennington, who says some of these names were written into Carter’s own copy – earned Carter a modest financial independence. It seems to have been this subscription, moreover, that brought Carter to the attention of Elizabeth Montagu, who pursued her acquaintance as she did those of others from whom she could benefit intellectually and morally. In this respect, the coming together of these two women at the center of a coterie in the late 1750s was a culmination, for Carter, of the formation she had undergone through her sociable literary connections of the 1740s and early 1750s.15

Elizabeth Montagu constructs a coterie

Meanwhile, Carter’s contemporary Elizabeth Robinson Montagu was embarked on a similar trajectory with respect to sociable literary exchange, albeit from the starting point of a talent for lively and entertaining letter-writing. As the young Duchess of Portland’s teenaged companion in the 1730s, Elizabeth Robinson displayed a ready wit that led to an early reputation in coterie circles, reflected in the circulation of stories of “Fidget’s” bon mots and in a letterbook kept by the Duchess of extracts from Elizabeth’s correspondence. Anne Donnellan, a member of the Duchess’s circle, writes to Montagu in 1745 in terms that demonstrate both the literary value attached to the familiar letter in general and the particular value attributed to this writer’s compositions: “Your letter is in your own strain … tis a valuable piece to add to my invaluable collection which I shall leave to posterity as a trophy that I had a friend who coud think so justly & so brightly, & in both or touch the collections of Pope Swift &c.” By 1754, Montagu’s written critique of Bolingbroke’s recently published Philosophical Works is being shown to the Archbishop of Canterbury.16 Montagu’s letters from the start display a tendency toward set-pieces – for example, on the significance of the sea, in the above-referenced letter to Donnellan – that might show up in altered form to different correspondents, suggesting her self-consciousness about the genre she is cultivating.

It is in her deliberate cultivation of ever-more accomplished correspondents and in her increasing tendency to discuss reading and ideas that Montagu parallels Carter’s exploration of the possibilities of scribal culture. As Markman Ellis has demonstrated in an illuminating analysis of Montagu’s epistolary networks of the 1750s, she moved steadily through a series of corresponding circles, from one comprised principally of family, wherein she discusses books with her husband and her sister Sarah and is assisted in Latin by her cousin William Freind, to one that centers on the poet Gilbert West (another cousin) and his family, and then through West (who died in 1756) to a core literary group consisting of Lyttelton (from at least 1756), Benjamin Stillingfleet (from 1757), Carter (from 1758), and Bath (from 1760). Ellis notes that by the late 1750s, Montagu’s correspondence with the members of her incipient coterie can be sharply distinguished from that with almost all her other contacts (the exceptions are her husband and her sister Sarah) by its discussions of reading, indicating the importance of intellectual exchange to this group’s identity. Of most importance to the identity and stature of this coterie, besides Montagu, was Lyttelton; as she writes after his death in 1773, “He was my Instructor & my friend, the Guide of my studies, ye corrector of ye result of them. I judged of What I read, & of what I wrote by his opinions. I was always ye wiser & the better for every hour of his conversation.” Lyttelton’s biographer Rose Mary Davis has asserted, in turn, that her subject’s “principal claim to importance at the time of his death was his position in the Blue-stocking circle.”17

A high-profile friend of Bolingbroke and member of the emerging Whig opposition to Walpole during the 1730s, Lyttelton held positions in the ministry from 1744 to 1756 while achieving considerable acclaim as an author (in 1747, his forthcoming Monody commemorating his first wife is announced by Birch to Philip Yorke as a notable literary event)18 and patron (Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones was dedicated to Lyttelton, and he is commemorated in the 1744 edition of James Thomson’s The Seasons). Nevertheless, Lyttelton’s political fortunes waned in the 1750s, in part because of his shift in allegiance from William Pitt to Chancellor Hardwicke and the Duke of Newcastle, and after the mid-1750s he found himself more or less in retreat at his country estate of Hagley (inherited from his father in 1751) and dealing with the fallout from an unfortunate second marriage. It was in this situation that his friendships with his cousin West, and through him, Montagu, developed. Even more deeply in the political wilderness since his widely condemned acceptance of an earldom in the negotiations following the 1742 fall of Walpole, Bath was seventy-six and had been widowed two years earlier when he became a member of Montagu’s inner circle in 1760. As these pre-histories show, although the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie made relatively intermittent use of print as a medium in comparison to its voluminous private writings, its members brought to the group established public identities.

Montagu makes some explicit statements, during the process of her own and her coterie’s formation, about her use of conversation and letters as the framework of a program of study that will allow her to develop intellectually and morally. Early in her marriage she writes gratefully that “Mr Montagu … is always ready to give me Instructions in whatever I am reading” and reports to him that in his absence she “rise[s] as soon as it is light & stud[ies] very hard when [she is] not obliged to be in Company.” In 1752, she writes about the Wests, “I am very happy in such neighbors, the whole compass of [our] Island does not contain Persons I esteem more highly nor in whose conversation I could find greater pleasure & improvement.” Six years later, she confesses to Carter,

I may be accused of ambition in having always endeavourd to ally my mind to its superiors, but I assure you vanity is not the motive, it is much more the happiness than the honour of Miss Carters friendship that I desire … When I was young I was content with the brilliant, if there was lacquer enough – I thought the object fine; now the brightest gilding, the finest varnish woud da[mp]en me, I must have solid gold, where ye real value surpasses even the apparent.19

Connections with literary circles did not simply mean second-hand knowledge gained through conversation; they could also mean first-hand access to the latest publications, at times even before they went to press. Thus, we hear the excitement in Montagu’s voice when she writes to her husband in 1746 that Conyers Middleton, her step-grandfather, has visited and let her read in manuscript “an account of the Roman Senate” that he will publish imminently, or to West in 1752 that she is sending him Archbishop John Tillotson’s life, left for him by its author, “Mr Birch himself,” after she has “read it thro’, & [been] charm’d with ye character.”20 For both Montagu and Carter, though from rather dissimilar starting points, expertise in the multimedia world of mid-eighteenth-century communications necessarily included the development of a sociable literary network and was embedded in its practices of conversation and epistolary exchange.

Thus, Montagu’s own fame expanded in the late 1750s as a natural continuum of that achieved already through her coterie activities as correspondent, conversationalist, and hostess. By the mid-1750s, Carter’s reputation as the joy of Plato and admiration of Newton, “equal’d by few of either sex for strength of imagination, soundness of judgment, and extensive knowledge,” was celebrated by John Duncombe in his Feminiad (1754); this reputation was only heightened by her Epictetus.21 By the time Montagu sought out Carter to become a member of her coterie in 1758, her epistolary overture shows a consciousness of the exchange being negotiated between her own social status, wealth, and reputation as hostess and conversational wit, on the one hand, and the learned accomplishment and moral force Carter will bring to the friendship, on the other. Montagu delicately positions herself as intellectually and morally inferior to Carter in order to offer a point of equilibrium to her diffident correspondent:

I can perfectly understand why you were afraid of me last year, and I will tell you, for you won’t tell me; … you had heard I set up for a wit, and people of real merit and sense hate to converse with witlings; as rich merchant-ships dread to engage with privateers: they may receive damage and can get nothing but dry blows. I am happy you have found out I am not to be feared; I am afraid I must improve myself much before you will find I am to be loved.22

What Montagu’s feminocentric coterie offered, then, was a kind of meritocracy that would allow middle-class individuals, especially women, to participate fully. Frances Burney’s much-later, rather satirical depiction of Montagu’s salon circle, as laid out “with a precision that made it seem described by a Brobdignagian compass” in its placement of “the person of rank, or consequence, properly, on one side, and the person the most eminent for talents, sagaciously, on the other,”23 nonetheless captures in a vivid image what must have been the coterie’s unique appeal in the 1760s and 1770s.

Literary production in the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie: script

As already suggested, the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie was the point of origin for a number of modes of literary production, making use of both script and print media. First and foremost of these was the familiar letter, the form at which Montagu excelled. Continuing the pattern already noted for the Bulstrode circle, a common entertainment of members of the coterie was reading preserved series of letters. At one point, for example, Bath offers an extended reader response to the Montagu–West correspondence of the early 1750s, which she has given him to read:

Ten thousand thanks to you Dear Madam, for the most agreable entertainment, I ever had in my Life, from reading. Nothing but your own Conversation can come up to it. My Passions were agitated just as I read; Sometimes in the highest Spirits, & then again dejected, & thrown into a sudden lowness of them from a melancholy line or two. If I found you under Affliction, for your friends, or describing your own sufferings, from Spasms, Convulsions and Reumatism’s, it was impossible not to suffer with you, & shed a Tear for your misfortunes. Then again, in an Instant Elated with excessive Joy, on the return of your health & Spirits, describing your Visit to Courayer, going thro’ a shopful of Toys and Vanitys to arrive at Wisdome, & clambering up a very difficult narrow pair of Stairs to get at Philosophy or relating a most ridiculous story of your Kinsman, young Worth, being caught in a Peice of roguery, & being in danger of the Galleys. In short your chearful descriptions of the beauty & Innocence of the Country, or your just severitys and Censures of the Follys and Wickednesse’s of the Town, are equally agreable.24

At another, in 1762, Bath has received from Lyttelton her letters discussing elements of dramatic tragedy in general, and of Shakespeare’s plays in particular; while he enjoys the manuscripts in their own right, we glimpse the germination of the project that was eventually published as the Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear, discussed below.

Such letter circulation served first and foremost, however, to establish and reinforce ties between members of the group. Truly exclusive circulation, explicitly designed for only one or two members of the coterie, is relatively rare in the surviving collection of its correspondence,25 while occasional poetry and other writings are used to reinforce group solidarity. One witty exchange, begun in late 1760, initiates a lengthy string of references that ties together the Montagu–Bath correspondence over a period of at least two years. The sequence begins with the eighty-year-old Bath addressing the forty-year-old Montagu in the plaintive strains of a dying lover; Montagu responds by graciously promising to hear his suit when she is double her present age, launching a millennium of love in the year 1800 (although Bath gallantly calculates the doubling of her age to arrive in a mere twenty years); Bath pleads for a reduction of the waiting period, protesting that while he can die for her he can’t promise to live for her. Subsequent letters refer constantly back to the tedious waiting period this admirer is enduring, mention that Carter is writing the epithalamium, compare Scott’s newly published novel A Description of Millenium Hall to the lovers’ proposed idyll, and so on. Although the original sequence appeared posthumously in the selected 1813 edition of Montagu’s letters, its contemporary “fame” was entirely based upon manuscript circulation. Thus, the Montagu collection itself contains two copies, at least one in a copyist’s hand, of Montagu’s letter to Bath, while she writes to her sister that she is enclosing a copy of “the billet doux of the witty and the gay Lothario [Bath]” (presumably with her reply included). At the same time, the earliest letters in the sequence trace the parallel circulation of a manuscript pastoral letter written by the Bishop of London, Thomas Sherlock, to the newly ascended George III. Montagu has received a copy from the Bishop (produced by his Secretary), which she sends on to both Lord Bath and the Duchess of Portland, requesting that Bath keep the letter “honourably placed … in [his] cabinet,” for fear “that by some accident it may be degraded by an appearance in a magazine or chronicle”; she “think[s] it necessary to put those restraints on the friends to whom I communicate it as may secure me from blame if ye letter should be made publick.”26

If Bath and Montagu are particularly gifted at creating letters with exchange value, it is Carter and Lyttelton who use poetry to articulate important moments in the coterie’s history. I will discuss later the odes produced by Carter to celebrate her visit to Tunbridge Wells with Montagu, Bath, and Lyttelton in the summer of 1761; in July of 1762, it is the turn of Lyttelton to send a poem entitled “The Vision” to Montagu in honor of a June visit to Hagley made by the Montagus, Lord Bath, the Veseys, and several others. This poem, of which a manuscript copy remains in the Montagu collection, was sent by Montagu to Vesey, Carter, Talbot, and perhaps others. Set in the author’s landscaped grounds, “The Vision” describes the speaker’s dream of a bard who first sees Bath as a towering oak, tended by Pallas and the druids, dispensing oracular wisdom to the British state, and then Montagu as a fragrant myrtle nursed by the muses and the virtues, sheltering Apollo. Thus the poem celebrates the physical gathering of the core members of the coterie and their spouses at Hagley (only Carter was absent), while asserting the importance of its members to the nation.

On another occasion, Montagu encloses to her close friend Lyttelton a witty, 139-line poem by their mutual friend Messenger Monsey spun out of a brief conversational exchange of December 5, 1758 (the exchange, apparently, consisted of “L: I must go to Eaton; M: You shall not go to Eaton”). Lyttelton replies to Montagu: “I return you Monsey’s Verses with some of my own. Upon reading his over again since I left you and Miss Carter together, his Muse caught and inspired me all in a sudden, as the Spirit of Fanaticism catches the Audience at one of Whitfields Sermons. If you like them, you may send them to him; if not, my excuse is, that they were conceived, born, and drest as you see them, in less than half an hour.” The poem itself and the surrounding exchange reinforce the mutual characterizations of the group: Montagu as beautiful and sensible lady, risking her own health in concern for her friends, Lyttelton as devoted admirer and cultivated courtly poet who can compose extempore, Monsey as whimsical and extravagant conversationalist. Similarly, the work a single letter can perform to reinforce the circle of the cultivated while excluding the uncultivated peer and the object of patronage is illustrated by a single paragraph in an undated letter of 1766 from Montagu to her Irish friend and fellow-salon hostess Elizabeth Vesey: “Lord Lyttelton desires Lord Orrerys wretched letters on ye English history may not be attributed to him neither as to ye matter or ye manner. I enclose a letter Mr Walpole wrote to Rousseau in ye name of ye King of Prussia. I have taken ye liberty to enclose 4 proposals for my friend Mr Woodhouse [a former shoemaker, discovered by Shenstone as a poet, and patronized by Montagu], as you love virtue & verse I am sure you will be glad to dispense of them for him, & it will be of great service to him to be introduced into Ireland under yr patronage.”27

These brief examples begin to demonstrate the circulation patterns of manuscript materials in the Montagu coterie and its associated networks: items move both within an inner circle of Montagu’s most intimate correspondents – Carter, Bath, Lyttelton, Monsey, Vesey – and also flow in from, and out toward, intersecting circles that include the likes of Scott, the Bishop of London, Walpole, Thomas Gray, Lord Kames, the Duchess of Portland, and at its farthest reaches, Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin. While some of the materials circulated in this way are political, they are not partisan in an early eighteenth-century sense – they are better described as nationalist and socially conservative. Their restricted circulation thus appears at once to elevate the social capital of the person who has obtained them (as was the case for Birch in Chapter 1) and to maintain links among a well-educated, patriotic but cosmopolitan elite that relies on manuscript circulation to maintain its shared sense of values.28

Literary production in the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie: print

This scribally reinforced solidarity translated into the conception and staunch support of publications on the part of members of the coterie. In 1759, Lyttelton published Dialogues of the Dead, which contained three dialogs by Montagu. The latter were contributed anonymously, but their authorship soon became known, and Lyttelton took pleasure in reporting their praises both before and after the general discovery of their authorship. Bath seems to have become acquainted with the volume through his friendship with Montagu, writing to her, “Last night after I left you, I read near threescore Pages, of Lord Littletons charming Book. You may divert your self, with your french Authors if you please, but I will back my Lord, against them all, either in Verse, or prose, throwing any Voltaire & Rousseau into the bargain, and leaving Old Aristotle or your friend Longinus, to decide the controversy.”29 The first publishing project of the fully fledged coterie, however, was the edition of Carter’s Poems on Several Occasions, published by Rivington in January of 1762.

Carter’s letters to Talbot during the Tunbridge visit of summer 1761 stand out for their light-hearted pleasure in the company of Montagu, Bath, and Lyttelton, entering into their teasing about her competition with the card-playing Lady Abercorn for the attentions of Bath, for example, and enthusing about drinking tea with Montagu after dark on the wild rocks of the seashore. It is in these letters that she half-complains of the “very serious difficulty” she is in as a result of “a plot contrived by Lord Bath and Lord Lyttelton, aided, abetted, and comforted by Mrs. Montagu,” to publish her poems.30 Immediately following the Tunbridge summer of 1761, as already mentioned, Carter produced two odes: one to Bath and another “To Mrs. [Montagu]” (which forms the epigraph to this chapter), celebrating the life of the coterie there, where “philosophic, social Sense” brightened the “Noon-day Sky” and softened the “peaceful Radiance of the silent Moon,” but also asserting that “lasting Traces” remain of those “happier Hours,” in the ensuing hours that the group’s members devote “to each Improvement …/ Which Friendship doubly to the Heart endears.”31 Montagu’s correspondence with Carter in the following months interweaves discussion of this ode with plans for the edition of poems. Thus, questions about the propriety of displaying the coterie in print – whether or not to include the names of Montagu and Bath, dedicate to Bath, and insert a Lyttelton poem written in praise of Carter at Penshurst Park – alternate with regret for the days of Tunbridge and with debates about the size of the print run. Lyttelton supplies copy, in the form of his Penshurst poem, Bath offers to pay for Carter’s stay in London during the preparation of the edition, and Montagu writes, “Let me have yr manuscript sheets, let me have the printed sheets, let me have as much to do as possible in ye business of your Book.”32

In the final phase of the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie, after the death of Bath in 1764, two very long-term projects issued from the press. One, Lyttelton’s History of the Life of King Henry the Second, published in five volumes between 1767 and 1771, was the labor of decades, during the latter of which Montagu had faithfully urged him on, and both she and Carter had read the manuscript; Lyttelton was complaining of slow printing as early as 1763, and reading parts of the work to Montagu in 1764. The second was Montagu’s 1769 Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear, Compared with the Greek and French Dramatic Poets, with Some Remarks upon the Misrepresentations of Mons. de Voltaire, a critical work which, as noted earlier, originated in epistolary discussions with Lyttelton initiated in about 1760 and which Bath had read as early as July 1762, immediately after the Hagley visit. Bath writes,

I will not yet send you back your own most Charming Letters to Lord Lyttelton, I will read them over & over again, and am greatly rejoyced to hear you design to go on with them … Observations, & Comparison’s of Modern Authors, with Ancients, Shakespear with Sophocles, is a work worthy of your Pen. Why do you say it shall never be seen, by any body but Lord Lyttelton, Mrs carter, and my self; for the vanity, or the praise it may bring, you need not print it, but surely the world ought not to be deprived of such a work, when it is finished.

In addition to illustrating the early genesis and coterie origin of the project, Bath’s exhortation offers a variation on the common theme of public usefulness with which the coterie’s members urged one another into print. While Montagu demurred, insisting that “as people generally profess to write for their own Amusement, and the instruction of their readers, on the contrary, I shall write for my own instruction, and the Amusement of my few readers,” the encouragements of Lyttelton, Carter, and Montagu’s sister eventually bore fruit. Even in the final extant letter of Lyttelton to Montagu before his unexpected death in August of 1773, potential publishing projects are being discussed: he responds to her urging that he write about the Roman history that, although the subject has been “exhausted” by “the most acute Understandings and most elegant Pens both of ancient and modern times,” “if the English Minerva [Montagu] will inspire my Genius with some portion of her Sagacity and Judgement, I will not despair of being able to say something New and worthy of Attention.”33

Two other cultural contributions of the coterie should be noted. The first is the epistolary travel writing of its central figures Elizabeth Montagu and George Lyttelton. The influence of such writings on the development of the commercially important genre of the domestic tour, and on the explosion in popularity of such tourism through the latter decades of the century, will be discussed in some detail in Chapter 6 of this study. The second significant development is in the group’s reception of the ballad and bard poetry of the second half of the century. If the manuscript circle and esthetic values cultivated by William Shenstone (see Chapter 3) led directly to the young Thomas Percy’s 1765 publication of the Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, Montagu, Lyttelton, and Vesey were in the vanguard of enthusiastic interest in, and critical reception of, such work. The coterie embraced the Ossianic poetry of James Macpherson from the time of its first publication in 1760 in Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the Highlands of Scotland, and Montagu’s correspondence shows her to be actively engaged in debates over the poems’ authenticity. The Montagu collection includes not only manuscript passages from Macpherson’s work circulated in advance of their publication but also an Ossianic imitation by Lyttelton and several related items of unknown origins – “Malvina’s Dream,” “The Death of Ela,” and “Down in yon Garden Green the Lady as She Goes” (a kind of Ossian-ballad hybrid labeled “For Mrs. Montagu”).34 In addition, the members’ correspondence includes frequent references to Vesey’s Bower of Malvina at her Irish home of Lucan, and London gatherings hosted by Montagu and Vesey are called “feasts of shells” and feature numerous “bards.” While in part the Ossianic language served as a cohesion device, almost a secret code, for the group, JoEllen DeLucia has also noted “the central role played by the Ossian poems in creating Montagu’s particular brand of Bluestocking sociability, which cast women as lead actors in the development of civil society.”35 Despite the disappointment of her desire to believe the Ossian writings authentic, Montagu does not waver in her tastes from her 1760 description of them as displaying “ye noblest spirit of poetry,” agreeing with Lyttelton’s assessment that if Macpherson has composed the works, he is “certainly the First Genius of the Age.”36 In this instance, we glimpse the coterie contributing to “modern” taste in endorsing the “past.”

Thus, the history of the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie and of the fame it attained through manuscript production and collaboratively conceived writing projects demonstrates the close integration of manuscript and print in mid-eighteenth-century literary culture and calls for a closer examination of the mechanisms governing this media interface. For a start, it is clear that a simple sequential model of media succession is inadequate to explain the dynamics at work in this moment, when manuscript and print media collaborated both to reinforce coterie culture and to establish literary reputations. These reputations, moreover, were not simply those of the core group; in the next section of this chapter, I will return again to Hester Mulso, now Hester Chapone, as an example of the effective patronage model practiced by Montagu.

Patronage in the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie: Hester Mulso Chapone

One feature of Montagu and Carter’s friendship from 1758 was a practice of pooling Carter’s middling and small-town connections with Montagu’s financial means and elite social networks to find suitable situations for women in various kinds of need. It was therefore inevitable that when Hester Mulso Chapone’s husband of only nine months died in September 1761, leaving his wife with almost no material assets, Carter would bring her young friend to Montagu’s benevolent attention. Montagu’s first expression of sympathy for Chapone comes in a letter written to Carter right after John Chapone’s death, and in the summer of 1762 she reports visits to Chapone, who was leading a peripatetic existence between the homes of various family members. We have already seen that a middling sort of egalitarianism had in part been the attraction of Richardson’s coterie, but also that theory fell victim to gender practices in the case of the unmarried Mulso and perhaps other young female members of the group. Montagu’s frequent representation of herself to Carter as the gainer by their relationship is very likely the approach she used in putting Mulso, now the widowed Chapone, at ease as well. Chapone writes to Carter in 1762 thanking her for making her acquainted with Montagu and adding that “I begin to love her so much that I am quite frightened at it, being conscious my own insignificance will probably always keep me at a distance that is not at all convenient for loving.”37

Montagu did bring the resources of her connections into play in an attempt to find a suitable employment income for Chapone. Montagu’s exchanges with her sister in the fall of 1762 show them discussing with their friend the Duchess of Beaufort the possibility of a position as governess and companion to the Duchess’s daughters. The sticking point was the fact that Chapone would not have been admitted to dine at the Duchess’s table, making her a servant rather than companion. Significantly, Montagu understands and respects Chapone’s position, writing to Scott:

I imagine Mrs Chapone wd not accept of service on any terms whatever. Her Brother who is very fond of her is in very good business, her Uncle is Bishop of Winchester, & tho she has a very small income of her own, yet leisure & liberty are of infinite value, to such a Person. She spent this summer at Kensington with her Brother who had taken a very genteel house there, & he treats her with great respect as well as kindness, & I imagine as soon as Mr Chapones affairs are settled ye Bishop will give her something decent, or get her some bounty in pennsion or employment of the King.

Montagu does not fault the Duchess, agreeing that she herself could never accept the notion of a female companion (“I must own I should as soon keep a person to blow my nose as to amuse me”), but she seems in this case to be able to imagine Chapone’s merit as demanding reciprocity across status lines.38

In fact, Montagu proudly cites to Carter a passage from a Lyttelton letter of October 1762 in which he places her in a triumvirate of female wits that includes Carter and Chapone; Lyttelton has written that “I have lately read over again our Friend Miss Carter’s Preface to Epictetus, and admire it more and more. I am also much struck with the Poem prefixed to it by another female Philosopher, whose name I wish you would tell me. If you will but favour the World with a few of your compositions, the English Ladies will appear as superiour to the French in Witt and Learning, as the Men do in Arms.” “The fine Ode is our friend Mrs. Chapones, but she does not own it,” Montagu replies to Lyttelton. It seems she continues to promote Lyttelton’s positive assessment of Chapone, so that in 1770, as the two women plan a trip to the North, Lyttelton writes courteously of his anticipation of their stop at Hagley en route: “I long to show my Park [to Mrs. Chapone], as her old acquaintance and friend, and as she is one of the English Muses, to whose Divinities it is consecrated.” On their return from the same tour, Montagu writes to Lyttelton, “When I have the pleasure of seeing your Lordship in Town I will shew you some poetical performances of Mrs Chapones which you will admire.”39 It is plausible that a little manuscript booklet of Chapone’s early poems, those of the Richardson era, found in the Montagu collection, dates from this promise to Lyttelton.40 Knowing Lyttelton’s commitment to those he patronized, it seems that the stage was being set for the coterie’s next push toward print, this time on behalf of Chapone.

From this same Northern tour, Chapone reports to Carter, “I am grown as bold as a lion with Mrs. Montagu, and fly in her face whenever I have a mind; in short I enjoy her society with the most perfect gout, and find my love for her takes off my fear and awe, though my respect for her character continually increases.” It appears that, as Montagu’s friend and now travelling companion, Chapone achieved with her an equilibrium that balanced the latter’s wealth, social power, and recent publishing success with her Essay on Shakespeare against Chapone’s monitoring of her friend’s practice of virtue in high life. Thus, this same letter to Carter continues, “[Mrs. Montagu’s] talents, when considered as ornaments, only excite admiration; but when one sees them diligently applied to every useful purpose of life, and particularly to the purposes of benevolence, they command one’s highest esteem.” And in 1772, Chapone writes approvingly to Montagu about the latter’s attentions to her mentally ill brother John: “Surely next to the happiness of self-approbation is that of seeing a friend engaged in a course of action that confirms & heightens all one’s esteem & admiration! No one bestows more of this gratification on their friends than yourself, and I must thank you as well as love you for being so much what I wish you to be.” This is a remarkable expression of moral monitorship on the part of a woman who, in the same letter, laments the fact that her “own little home” does not “admit air enough for [Montagu] to live in two or three hours sometimes,” and concludes by hoping “for the favour of a Summons when you are settled & composed in Hill Street after yr Journey.”41

Montagu, in her turn, is “charm’d with the rectitude of [Chapone’s] heart & soundness of understanding. She is a diamond without flaw.”42 It is from this post-Richardsonian coterie context, founded upon similitude of gender and intellectual interests and exhibiting a carefully calibrated balance of material property and status versus uncompromising moral rectitude, that Chapone’s second phase of fame issued. While financial need was certainly an incentive, Chapone’s stance of moral authority can be seen in the first choice of work, an educational treatise in the form of letters to a younger woman (originally her niece) entitled Letters on the Improvement of the Mind. But the work also proudly wears the endorsement of the particular coterie to which Chapone belongs, in the dedication acknowledging Montagu’s encouragement, critical judgment, and suggestions for revision. It is “the partiality of [Montagu’s] friendship” which has led the author to believe that the letters might be “more extensively useful”; in effect, the coterie authorizes the print publication as a means of meeting its broad social aims.43

As Sylvia Harkstarck Myers asserts and the bibliographical work of Rhoda Zuk has confirmed, Chapone’s Letters “was the most widely read work of the first generation of Bluestockings.”44 Thus, Mrs. Chapone, through a second experience of a literary coterie, was put into a position that allowed her to make constructive use of the “uncommon solidity and exactness of understanding” that Elizabeth Carter had recognized in Miss Mulso twenty-three years earlier, but which had contributed to uneasy relations in the Richardson circle at North End. E.J. Clery has suggested that Chapone’s Letters served as “a manual for the creation of future generations of Clarissas” and therefore as a realization of Richardson’s hopes for Mulso and his fostering of her abilities “by private debate.” While this claim is valid in its recognition of the continuity between the two apparently disparate phases of Hester Mulso Chapone’s career, it is only ironically so, because a coterie with Richardson at its center could never quite give its blessing to the notion of, in Clery’s terms, “private debate as preparation for more public interventions.”45 By contrast, as Chapone’s experience with the dedication of her Letters to Montagu illustrates, the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie was prepared to exert its collective cultural influence by endorsing print publishing projects, such as Chapone’s, that it deemed of personal and public benefit.

Catherine Talbot’s rejection of coterie authorship

And what of Catherine Talbot, another woman admired by Richardson and Edwards for her literary accomplishments, as we saw in Chapter 1? What was her trajectory through this shifting landscape of coteries? The final portion of this chapter will trace the sequence of Talbot’s significant engagements with several coterie networks, while noting her paradoxical determination to shield her literary productions, whether in script or print, from every sort of public exposure. Her story thus underscores by contrast the fact that well-received coterie writing did not inevitably lead either to print or to the identity of author, even in the interdependent media climate of the mid-eighteenth century. As already noted, Talbot’s primary, mostly elite literary connections were with members of the Yorke–Grey coterie, established through her childhood friendships with Mary Grey and Jemima Campbell and carried on into the exuberant and creative coterie life at Wrest Park. In the year 1751, however, Talbot and her mother underwent the upheaval of moving from their longtime home, the rectory of St. James, Piccadilly, in the most fashionable part of town, to the Deanery house of St. Paul’s Cathedral, in the heart of the City. While the friendship with the Marchioness and other women of the Yorke family continued, there seem to have been tensions marring the former intimacy and trust. Shortly after the move Talbot is hopeful that, paradoxically, she will see more of her friends because more formal planning of visits is necessary, but she often expresses a sense that the geographical divide is paralleled by a growing psychological and social gulf separating her from the leisured lives of Grey and the others of the Yorke circle: “they live in a world vastly separate from ours, and cannot enliven many a lonely evening when you, dear Miss Carter, will be kindly at hand,” and they are victims of “that cruel influenza, the enchanted circle of dissipation and amusement.” For Grey’s part, she regrets “the Confinement & Tristesse of St. Pauls” to which her friend is subject.46 An important connection formed in the early 1750s reinforces the sense that Talbot was consciously seeking relationships of greater intellectual and moral depth: in 1753 she sought out the elderly Duchess of Somerset, who as the Duchess of Hertford was at the center of the coterie that had anchored Elizabeth Rowe’s late-life fame, and had more recently been an important patron of James Thomson.47 The two women formed an immediate and strong bond that was cut short by the Duchess’s death in 1754. Though brief, the friendship was characterized, again, by the typical practices of scribal culture – while visiting the Duchess at Percy Lodge, Talbot read the manuscripts of Rowe; she in turn introduced the Duchess to Edwards, with whose sonnets the Duchess was “charmed”;48 and she composed an educational fairy tale for the Duchess’s grandson.

The Duchess’s death, however, left Talbot with the just-genteel, morally earnest Richardsonian circle, discussed in Chapter 1, as ballast to her relations with the more elite “enchanted circle of dissipation” in which she was required to participate to some extent but about which she felt highly ambivalent. Indeed, it was shortly before this that Talbot encountered and greatly admired Clarissa, writing to Carter, upon discovery of Richardson’s insertion of Carter’s “Ode to Wisdom,” “Are you so happy as to be acquainted with these Richardsons? I am sure they must be excellent people, and most delightful acquaintance.”49 As Clery puts it, “by making Clarissa and Anna Howe studious, articulate, critical, perpetually scribbling young women from genteel families, [Richardson] made a direct appeal to their counterparts in real life.” She goes on to suggest that the conjunction of Johnson’s Rambler and Richardson’s work on Grandison, together with new publications by Cockburn and Lennox that she promoted, “aroused in Talbot a renewed enthusiasm for participating actively in the literary public sphere.”50 Talbot obviously felt a strong affinity for the novelist’s thematic preoccupations and supported his authorial aims; with the move to St. Paul’s, she became his neighbor and began to record his regular visits in her journal.

Indeed, this relationship drew Talbot into intense editorial involvement in the writing of Sir Charles Grandison. While Richardson’s biographers imply that Talbot overestimated her position as in reality only one among many “ladies” whose counsel Richardson never really intended to follow, they acknowledge that “there is no reason to doubt that a good many of her painstaking corrections were accepted.”51 Indeed, there is no record of a similarly extensive editorial role to that played by Talbot (with the participation of Secker). She devotes eighteen or more months to “our Incomparable Manuscript which I am reviewing as Carefully & I could almost say as Conscientiously as I can” and engages in hours-long consultations with the author, during one of which “four Volumes [are] dispatched.” That Richardson too was taking this process very seriously is implied when Edwards indicates in the summer of 1752 and again in 1753 that his friend is waiting with bated breath for the return of his manuscript or printed sheets from Cuddesden, the summer home of Secker and the Talbots. Carter writes to Talbot, upon receiving from Richardson the first four volumes of the novel, that “Every body, I am sure, will be struck with the advantageous differences of the language, though but few can observe it with the peculiar pleasure that I do.”52 Given the unique combination of attributes Talbot brought to the project – intelligence, good taste, an insider’s knowledge of the manners and attitudes of social elites, and a sincere commitment to their moral improvement – her advice must have been invaluable in the composition of a book that, if criticized by some of her friends for such features as Harriet Byron’s talkativeness and Sir Charles’s foreign education, was by the same measure successful in becoming the subject of fashionable conversation.53

Although she retained her loyalty and respect for Richardson when other members of the coterie had distanced themselves, Talbot’s outsider position with respect to her two coterie groups is neatly captured in her 1756 report to her friend Anne Berkeley, widow of the Bishop of Cloyne, that she has visited Richardson in his new suburban residence of Parson’s Green, in “an Arbour as pleasant as a Yew Arbour can be, that is besides decorated with indifferent Shells & bad Paintings, but the Air was sweet, the Garden gay with Flowers & the Company Agreeable.”54 At the same time, even more than for Mulso, it seems to have been her relationship with Carter that served as ballast for Talbot through this period of division. I have shown throughout this study how the two women debated and collaborated in their relationships with Richardson and Johnson as authors – it was this bond with one another that flourished beyond the life of the Richardson coterie, as Talbot embarked on the long project of assisting with and obtaining subscriptions to Carter’s publication of her translation of Epictetus, which finally appeared in 1758, and indeed beyond Richardson’s death in 1761.

Talbot, of course, did not need the patronage of either Richardson or Montagu. While Carter was becoming Montagu’s friend in the aftermath of Epictetus, she was taking up life at Lambeth Palace as a member of the household of Thomas Secker, now Archbishop of Canterbury; there she often served as his secretary and as a conduit for managing the clerical patronage that went along with his office. References to Montagu in the Talbot–Carter correspondence as Carter and Montagu become increasingly close suggest that she and Talbot were not prior friends, though by the 1750s Montagu was moving in a similar social sphere, and there is a reference in the Mary Delany correspondence for 1754 to a simultaneous visit from Miss and Mrs. Talbot, Montagu, and the Duchess of Portland. We see Carter initially mediating the relationship, with Talbot writing in June 1758 that she now loves Montagu “twice as well as usual for the justice she does to you, though, she must be blind not to see and feel your merit,” and Carter expressing the wish, in November 1758, that Talbot “will see [Montagu] often, as I am persuaded the better you are acquainted with her, the more you will be convinced of the excellency of her character.”55 By the 1760s, both Talbot’s and Montagu’s letters to Carter mention regular contacts between them in the form of notes, messages conveyed by mutual friends, and visits. Often the two women combine forces to patronize or promote worthy junior clergy, women fallen on hard times, and authors of morally improving works.56

Nevertheless, Montagu’s references to Talbot in her correspondence with Carter frequently mention the awkwardness of their friend’s residence at the Archbishop’s palace in Lambeth, on the south side of the Thames, suggesting that once again a geographical barrier separates Talbot from full participation in a literary coterie. This physical impediment can be taken to stand for not only the more insurmountable social barriers of Talbot’s duties in relation to her elderly mother and the Archbishop (exacerbated by the relatively public nature of his household) but also the more long-standing psychological or ideological ones of Talbot’s extreme reluctance regarding any sort of circulation of her writings. Thus, just as Richardson’s surviving correspondence contains only one brief, rather formal note of New Year’s greeting from Talbot, there is but a single surviving letter from Talbot to Montagu. Demonstrating the importance of Carter’s mediating role in this relationship, the witty and engaging letter sent to Tunbridge in 1761 responds to the plan being devised for the publication of Carter’s poems, addressing Montagu as “the Lady of the Rose colour’d Gown” and assuring the circle at Tunbridge of Talbot’s own “readiness to obey the Commands of Lady Ab:s Tunbridge Cotterie.” The letter concludes with the hope that Montagu will “sometimes in your Airings … have the Charity of bringing an Hours Cheerful Improvement to this Retirement [Lambeth], which wants so many of the Rural Joys of the real Country, that only such a Neighbour as You can reconcile one to its nearness to London.” And yet, where the recipient might have been drawn into further correspondence in response to this jeu d’esprit, Talbot in fact shuts any such possibility down, facetiously observing that Montagu is now in Talbot’s debt for a reply after an entire year’s interval, “for since you have been rash enough to begin I am resolved I will be wise enough to go on.” Knowing well the rules of scribal exchange and possessing the literary talent to shine in this milieu, Talbot nevertheless chooses to remain on its margins rather than fight against the circumstances that have placed her there.57

If Talbot did not need patronage to live, she certainly eschewed the publicity afforded by coterie circulation of manuscripts. It is possible that her determined efforts to avoid such publicity – what she would have considered notoriety – explain the above-noted lack of letters in the correspondence of individuals such as Richardson and Montagu, both of whom were well known for the circulation and reading of letters within their coteries and beyond. Her consistently expressed dismay at the propagation of her manuscript writings appeared extreme even to her fellow coterie members, who teased her with threats of sending her letters to the Magazine of Magazines, or were simply bewildered, in the case of the Duchess of Somerset, when she would not even allow the Duchess’s grandson’s tutor to see the educational fairy story she had written for the child.58 But despite her efforts at secrecy, Talbot’s juvenile writings, especially, continued to circulate in scribal networks, returning to haunt and discomfit her. In 1745, for example, she writes with dismay of a group of visitors to Wrest including a Mrs. 15.5 [“P—e” in Talbot’s code] who “struck me down at once with talking of Verses of Mine forsooth that she had seen at Bath 14 Years ago. Well, if she did then see some follies of a Child, are they to be reproached her on to Four score … They [Yorke and Grey] make themselves vastly merry with the numberless Persecutions I undergo, & my hatred to this detestable Fame.59

Birch’s letter-books contain copies of one of the works Mrs. 15.5 might have heard of – not a child’s poem, but a more recent witty letter of welcome to her newborn cousin, written in 1742. Sometime after 1761, Talbot writes to Eliza Berkeley, wife of George, in response to having been sent a copy of this same 1742 letter, of her disappointment a finding “the Ghost of my own poor Letter (that has been dead & gone so many Years) still walking about the World & Haunting me even here.” Zuk reports that a revised version of the letter appeared in print in The Gentleman’s Magazine a month after Talbot’s death, as “Letter from the late Miss Talbot, to a new-born Infant, daughter of Mr. John Talbot, a Son of the Lord Chancellor.”60 Talbot’s experience with the long-term uncontrolled circulation of her manuscript writings thus makes her the unwilling proof of Harold Love’s observation that “[s]cribal publication, operating at relatively lower volumes and under more restrictive conditions of availability than print publication, was still able to sustain the currency of popular texts for very long periods and bring them to the attention of considerable bodies of readers” – even in the supposedly more attenuated scribal culture of the mid-eighteenth century.61

By contrast, Carter’s publication of Talbot’s works, shortly after her friend’s death from cancer in January 1770, was presented as entirely a print undertaking rather than as mediated by a coterie: unlike the edition of her own Poems eight years earlier, Carter had the works published at her own expense and presented them directly “to the World in general,” rather than as a subscription edition or as in some way endorsed by a group. Zuk records seven London editions between 1770 and 1772 of a Talbot work completed in manuscript as early as 1754, the devotional Reflections on the Seven Days of the Week; this success was followed by compilations of her essays and poems. Thus, although Talbot’s posthumous reputation was eventually absorbed into that of the “Bluestocking” women through her association with Carter and the publications of Carter’s nephew Montagu Pennington, her fame was for some decades her own.62

From a media cultures perspective, therefore, Talbot’s writing life serves as a foil to that of Chapone: instead of achieving the continuity between coterie and print modes represented by the title of Chapone’s Reference Chapone1775 Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, By Mrs. Chapone, Author of Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Talbot’s career remained fragmented to the observer until Carter created the posthumous vehicle that coalesced and shaped her reputation. This fragmentation, I wish to underscore, is the consequence not of a life lived in coterie circles, but rather of a lack of desire, or freedom, to exploit the modes of circulation offered by either manuscript or print practices of the period. Where Chapone was able to multiply her effectiveness as an author by joining the forces of coterie and print cultures, Talbot worked assiduously to thwart their combined efforts to draw attention to her. Nevertheless, her achievements in actively proposing, encouraging, and furthering the writing of others, not only in terms of patronage, but also to the extent of significant editorial labor, should not be undervalued. In these respects she was playing almost all the important roles of the member of a literary coterie, and during her lifetime, her influence on the world of print was arguably as great, however invisible, as it could have been through her own print publications.

Although the core members of the Montagu–Lyttelton coterie held no current institutional offices and subordinated any participation in the commercial literary world to their identities as aristocrats, retired politicians, coalmine owners, estate managers, salon hostesses, housekeepers, educators, and friends, they saw themselves as holding a position of public significance. The mixed-gender coterie centered by Elizabeth Montagu registered successes on the multiple fronts of social, literary, and even political power. It might be said, and surely was felt at the time by members of this circle, that they had acquired the ability to fully exploit the potential of the interconnected media forms they cultivated, when schoolboys were assigned compositions comparing Carter and Montagu to “determin[e] the just merits & standard of a literary female,”63 or French and English observers debated the effectiveness of Montagu’s attack on Voltaire in her Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear, or extensive networking procured an Oxford doctoral degree and a royal pension for her protégé James Beattie in 1773.

Indeed, a letter written to Montagu by Sir John Macpherson of Madras India in 1772 draws together her literary and political power in a compliment she must have relished:

How much, Madam, have I been obliged to the Genius of Shakespear illustrated by thine! For a whole year, that I spent at Sea in my passage to this place, both afforded me the highest pleasure I could enjoy in my Situation … I sincerely hope the dark gloom of politicks which deaden’d ingenious and Elegant life in London in the years 69–70 has vanished before now. George the third does not know how much he is indebted to the chearful and Classic Assemblies of your Chinese Room. You gave that sweetness and refinement to the thoughts of our Statesmen which could alone counteract the acid and gloom of their Dispositions … indeed, Madam, we are all indebted to you; and that without your being sensible of it.64

Such recognition, especially the acclaim with which Montagu’s Essay on Shakespear was received, along with its symbolic engagement of Johnson’s own 1765 edition of Shakespeare, might have appeared to vindicate equally the dual routes to cultural power taken by Johnson and by Carter, Montagu, Chapone, and even Talbot. In Chapter 5, however, I will explore the fortunes of Montagu after the death of Lyttelton, tracing how Montagu’s embrace of her patronage power and her broad, print-based fame, along with changing conditions in the literary landscape, created conflicts that erupted in the quarrel of Montagu and her friends with Samuel Johnson over the latter’s “Life of Lyttelton,” published in 1781.