Male sex work as an occupation is as old as its female counterpart. There is little evidence from the historical record that male sex work was not present in any society where female sex work operated. Then and now, the primary buyers and sellers of male sexual services have been men. As such, male sex work has always carried the added stigma of homosexuality, causing male sex to be socially distinct from the more widely practiced female sex work. In ancient Greek culture male prostitution went by the name porneia. The term distinguished male sex work both from the accepted paederastia, relationships that existed between old and young men, porne (female prostitution), and hetaera, female mistresses.1 This distinction was more than linguistic. There were social restrictions on what a male sex worker could do and be even if he were no longer active in the profession, which did not apply to those in paederastia.2 Greek law forbade those who had been involved in porneia from addressing the Athenian assembly. Even in a culture with relatively lax attitudes towards homosexual sex, men providing sexual services to other men commercially were not granted the full privileges of citizenship.3 Whether or not porneia was a crime was beside the point, the very involvement in the market as a man who sold sexual services to another man was enough to render one socially cut off from political power.

Scholars have claimed that male sex work in ancient Greece operated to exacerbate existing class inequalities. Young men of the upper classes could avail themselves to a sexual and social mentor via paederastia, while young men from less advantaged backgrounds participated in porneia and faced the lifelong consequences of those choices. The actual practices between the two differed primarily through the social expectations of the relationship. While young men in paederastia could expect to be mentored by their older patrons and exposed to the arts, politics, and social norms of the upper classes, young men in porneia could not. The explicit commercial exchange inherent in porneia relegated it to an undesirable social exchange.

In the Roman Empire, men could legally engage in sexual acts with other men in exchange for money as long as their participation was voluntary and their services were not offered as servants.4 Male sex work could be secured by anyone – unlike other services in the Roman Empire, one need not be a citizen to be a buyer. Given the social class hierarchy, Roman citizens were discouraged from offering a sexual service to slaves, foreigners, or others of lower social standing. These social restrictions on male sex work made the practice particularly unappealing for Roman citizens. This meant that male sex workers largely came from the slave or foreigner classes. By the fourth century BCE political acts which restricted the number of slaves and foreigners reduced the supply of sex workers and led to increasing prices for male sex work. Polybius noted that male sex workers were regularly secured for a talent (more than several months of wages for the average worker) and Cato complained that sex workers were priced higher than farmland.5 With little in ways of counts of male sex workers, however, it is difficult to know how much of the price increases were driven by increased demand from Roman gentry as opposed to the supply restrictions.

The large-scale acknowledgment of the practice in the Roman Empire also comes from public policy. Beginning with Caligula (37 CE) and lasting approximately until 500 CE, the Roman Empire taxed the earnings of all sex workers and formal registration of the occupation was common. Historians now believe that while these policies legitimized male sex work, they also brought the profession to light and therefore discouraged many men from entry. The private practice could be tolerated, but public disclosure of the occupation was not. Archeological work has found evidence of male brothels, however, suggesting that public meeting places for male sex workers and their clients occurred with some regularity. The brothels have been identified through markings and depiction of homosexual sex in the building. The presence of male brothels in the Roman Empire has been used as evidence of the relatively open attitudes towards male homosexuality.6 In ancient Greece, young men would grow their hair out and wait at male establishments such as barbershops for clients.7

As with Greek language, different terms were applied to male sex workers in the Roman Empire. Male sex workers were referred to as exoleti, while younger sex workers were known as pueri delicate and catamati. Unlike its earlier Grecian form, male mentorship by elders did not include sexual interaction. The lack of sex in mentoring relationships may be related to the professionalization of sex work. Another factor would be the growing Christianization of the Roman Empire, which led to decreasing social acceptance of male sex work and homosexuality in general.8 By the end of the sixth century a growing distinction related to homosexuality caused even starker social distinctions between male and female sex work. As early as 390, penalties were harsher for selling a male into prostitution, and by 533 all homosexual acts, commercial, consensual, and coerced, were punishable by death.9

The history of male sex work is not confined to the West, although there are fewer historical sources specifically referencing the practice. In Japan, for example, kabuki was a place for commercial sex between men. While monks and Samurai warriors engaged in pederasty in a manner similar to the practice in Greece, kabuki commercial sex was largely practiced between social classes. This practice continued until the seventeenth century, when sexual conduct between men of different social classes was outlawed by the Tokugawa government.10

The existing literature on the history of male sex work does lead to some general assumptions on the way the practice existed in historical settings. The ancient practice of male sex work was socially and legally distinct from older/younger sexual relations and from female sex work. A key distinction in historical male sex work was the class difference or similarity between buyers and sellers. Class differences were grounds to label the practice as sex work, and this meant that the historical practice of sex work was, in general, something that took place between classes. Male sex work was a service procured by those of high social status and supplied by those of low social status. Within the same social class, however, the practice was generally taboo and discouraged. From the historical scholarship, we find that the commercial aspects of the market were embedded in social ideas about who could (and should) supply and demand sexual services between men.

Male sex work has always had to contend with changing attitudes toward homosexuality. In periods and places where homosexuality was socially accepted, male prostitution was more likely to be professionalized along with its female counterpart.11 When and where homosexuality became taboo, male sex work and all homosexual practices were commonly grouped together and sanctioned. Even in ancient times, the social acceptability of homosexuality had direct effects on the social acceptability of male sex work. This is not to say that male sex work disappeared, but the social recognition of male sex work appears to be related to the social recognition of homosexuality. This is in stark contrast to female sex work, which was commonplace, and was always separated socially and legally from heterosexual social relations such as marriage.

In medieval Europe, social sanctions on male homosexuality continued the practice of the late Roman era, which grouped male sex work and homosexuality together. In many instances, both were punishable by death. Indeed, in order to be allowed entry the priesthood, a man could not be discovered to have been involved sexually with another man.12 Despite these legal and social sanctions, male sex work continued to be practiced. Historical records now point to a renewed linguistic distinction between homosexuality in general and male prostitution in particular in the Renaissance, where the term bardassa came into use to describe men engaged in sex work.13

By the end of the seventeenth century male prostitution was institutionalized in almost every major European city. This institutionalization included public knowledge (for those desiring such information) of the places where male sex work could be purchased and a language that facilitated the commercial activity. In Victorian London, for example, the Piccadilly Circus was well known as a place where one could purchase male sex work services. Men would adopt styles that would advertise their occupation, such as playing with one’s lapel or wearing distinctively colored clothing. There is also some evidence that the urban male sex work of this time had changed from passive young men seeking to sell their services to dominant older men, to one where passive older men sought the sexual services of dominant young men.14 Without comprehensive information, however, it is difficult to draw general conclusions. While still a criminal act, the prosecution of such crimes was relatively lax. When punishment was meted out, it was rarely as draconian as in earlier periods, owning to the relatively liberal attitudes toward homosexuality in European urban centers.

American male sex work predates the founding of the United States. Although the colonies prosecuted men for sodomy, and in more than ten cases executed men for the crime, some of these cases are known to have involved elements of solicitation. In May of 1677, Nicholas Sension was tried for the crime of sodomy. A deeper reading of the historical record reveals that the crime was not simply one of homosexuality, but of solicitation. In the court documents it was revealed that Sension had a long history of propositioning young men in the surrounding community for sex. Sension had been privately reprimanded for his activity at least twice over more than 20 years of known attempts to have sex with other men in return for compensation. In his sodomy trial it was revealed that he had, in at least two instances, offered payment in exchange for sexual services. Samuel Barboe testified that Sension offered him a bushel of corn if he would disrobe for him, and Peter Buoll testified that Sension offered him gunpowder in exchange for “one bloo at my breech.” Sension was convicted of sodomy, but his sentence did not meet with any jail time.15

Historians note that this trial, and its instances of sex for payment, reflects the class distinctions in male sex work that were present in ancient times. Sension was a prosperous landowner in Connecticut and most of the men who accused him were of lower social class. Sension was first privately sanctioned to stop propositioning young men, and was only publicly tried when he attempted to sue his indentured servant for slander because that servant, Daniel Saxton, wished to be released from service due to Sension’s numerous sexual advances. Only after Sension took legal action against his servant was he investigated and brought to colonial justice. As Saxton defended himself against slander, he showed that Sension had a history of sexual advances toward young men that involved payment. Given the private investigations and warnings that had been issued in the past, it is likely that Sension’s acts would have gone uninterrupted had he not sought to silence Saxton.

In the nineteenth century, male sex work on both sides of the Atlantic was institutionalized in large industrial cities. Part of this was due to ever-increasing urban population and the greater personal freedom allowed in urban areas, but there were also legal developments in Europe. In the early nineteenth century, the Napoleonic Code ended legal sanctions against sodomy. Given the fact that the First French Empire ruled a significant portion of the continent, the decriminalization allowed the male sex trade to flourish from Paris to Berlin. Male sex also flourished in American cities. For example, in 1899 the New York City Vigilance League found that the Bowery district contained more than five places where male prostitution was well known. Reports at the time suggested that there were more than 100 male sex workers in New York City. Given the size of the city and the generally hostile attitudes toward expressions of same-sex desire, this number of male sex workers speaks to the prominence of male sex work in urban areas at the time.16

This modern form of male sex work operated under different norms than earlier variants. While it was still the case that clients were older than providers, on average, the sexual roles assumed by each took on a different routinized pattern. The class distinctions of the earlier era married to a new form of industrial masculinity, which conferred upon young working-class men an authentic masculinity that they traded for money. The higher-class clients were more likely to assume a passive sexual role and the male sex workers were prized for their masculine appearance and sexual conduct. Men in the military were particularly popular as sex workers if they acted as “trade,” presumably heterosexual men who were temporarily engaging in homosexual sex for compensation. Weeks (Reference Weeks1989b) notes that military members were also thought to be more trustworthy and ethical in their dealings with clients.

Modern sex work was more intimately tied to increasing recognition of sexuality and masculinity. While cities openly noted that the fairy – effeminate man – was a commonly encountered urban inhabitant, male sex work in urban centers was not focused on effeminate men. There were cross-dressers and transgender sex workers, who sold either the illusion of femininity or transgender sex work to male clients, but male sex workers were primarily prized for their masculinity.17 The sexual identity of male sex workers was less important than their ability to provide an authentic masculinity to clients who desired the new industrial masculinity that was developed during this time. With the primacy on masculinity, the earlier notion of the young sex worker gave way to an older sex worker would could more reasonably convey adult masculinity. Sex work moved from being about youth to being about adult men engaged in a commercial exchange for sex.

The dawn of the twentieth century presented a modern form of sex work that bore striking similarities and differences with regard to ancient and medieval practices.18 First, sex work then and now constituted an average age difference between client and sex worker. Older men, who were more likely to be able to afford such services, made up the largest proportion of the client base. Young men, some of whom were in fragile economic circumstances, were likely to be service providers. Second, there were significant class differences between sex workers and their clients. As Friedman (Reference Friedman, Minichiello and Scott2014) notes, this was different from the earlier class distinctions in male sex work, in that the new class distinction was predicated on the authentic masculinity afforded to working men in the modern era. Third, the change in the relationship to one that was transaction-specific was due to the fact that the circumstances surrounding sex work had changed. No longer was sex work part of the mentored relationship between men that also included some monetary and perhaps non-pecuniary compensation. Sex work by the end of the nineteenth century was an occupation.

By the beginning of the Gay Rights movement in the twentieth century, male sex workers had carved out a key niche in urban gay spaces. They had become an archetype in gay culture and they played a key role in public representations of gay people. Importantly, sex work became embedded into gay communities in a different way than it was for heterosexuals. Part of this is because the history of male sex work sought clear distinctions between commercial and noncommercial relationships between men. Without the sanctions of marriage and other traditional recognitions for family forms, the sexual relationships between men have been placed in a different sphere, putting them into closer social contact with male sex work and male sex workers.19 For example, in the early and mid-twentieth century United States, many gay establishments would be frequented by male sex workers and men who desired noncommercial sexual encounters. This is not necessarily because the two groups desired to be in close contact, but because the limited number of social spaces safe for male homosexuals left little room to demarcate spaces for subcultures.

This close social relationship has allowed male sex workers a prominent position in social representations of male homosexuality. When anti-gay political commentators made note of the alleged perversity of gay men, they most commonly cited the cases of young men who entered into prostitution relationships with older men as a rhetorical technique to label gay men as pedophiles and gay relationships as inherent power imbalances between old and young men. Young men became natural embodiments of “innocents” who were “victimized” by older men who could entice them into sexual exchanges that provided money that the young men needed to survive. Ironically, these charges were coming at a time when young men as a fraction of the male sex worker population were on the decline given the changing nature of male sex work. Still, the age distinction between clients and sex workers and the ingratiation of male sex work into urban gay spaces proved to be problematic as gay men sought social acceptance for homosexuality, while at the same time maintaining close contact with an arrangement considered as vice even in its heterosexual form.

At the other end of the spectrum, gay men themselves had begun to develop an archetype of the gay male hustler, a presumably heterosexual man (but clearly an adult) who provided sexual services to other men. The development of a unique gay masculinity in urban spaces borrowed from the archetype of masculinity offered by male sex workers. Although the growing acceptance of homosexuality in urban communities led some gay-identified men to provide commercial sex services, the archetype of the male hustler (and the industrial masculinity he offered) did not fit into the anti-gay narrative, but rather molded into contemporary constructions of urban gay masculinity.20 The male hustler was a man’s man – a masculine man with few (if any) observable traits that would label him a homosexual. In the scholarship on male prostitution in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, this modern male hustler archetype featured prominently.21 This type of male sex worker was a “hoodlum” or “thug” who sought to use prostitution for wage income, rejecting the formal labor market. The fact that these men were presumably heterosexual added to their allure in a gay subculture that socially celebrated nontraditional representations of masculinity, but still held traditional male masculinity as a sexual ideal. In fact, the development of modern male physique and bodybuilding industries has direct links to male sex work. Men in the earliest era of bodybuilding would seek male sponsors, an arrangement that would allow them to concentrate on weight training. The early history of physique modeling is replete with men who used their masculine and muscular appearance in exchange for remuneration that freed them from the formal labor market.

The fusion of modern conceptions of masculinity, which imbued working-class and lower-class presentations of aggressive men as inherently masculine, did have effects on the ways that male sex work operated in modern urban environments. Some male sex workers who adopted gay identities found that clients demanded “trade” – men who did not identify as gay but who participated in homosexual sex. Gay identified male sex workers would be inclined to describe and present themselves as “trade” for their clients. In a market where desire and demand are closely intertwined, male sex work began to take on more performance elements than before. This also meant, however, that the range of sexual practices expanded and could not be presumed on the basis of one’s position as client or sex worker.

In the most popular depictions of male sex work in mass media, male (homosexual) sex work has been depicted as a last resort for heterosexual men. Although the films Sunset Boulevard (1950), Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), Midnight Cowboy (1969), American Gigolo (1980), and Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo (1999) as well as the television series Hung (2009) and Gigolos (2011–) are the most popular media images of male sex workers, they actually present the least-typical part of the market. Women are very rarely the clients of male sex workers. In fact, the (heterosexual) male escort agent featured on the reality television series Gigolos noted that the escorts he employs cannot support themselves through work with female clients. Indeed, the program, despite being billed as authentic, has had to remunerate female participants, and some have never been clients of the featured escort service. The popular image of a male sex worker as a gigolo stands in contrast to the limited evidence that women have ever made up anything more than a negligible fraction of the client base for male sex workers.

Gay films and art films of the same era depict male sex in a manner closer to the most common experience, which is to say they depict male sex work as homosexual activity. My Hustler (1965) contains two half-hour vignettes of male sex workers. Both of the scenes are explicit in noting that male sex work is the buying and selling of sexual services by and for men. The documentary style of the film and its explicit homoerotic content were some of the first homosexual representations of male sex work. In The Boys in the Band (1972), a male sex worker is hired as a birthday gift, and the price of his services is discussed in the production. As public and academic discussion of homosexuality and prostitution moved to the mainstream, so did the concept of the homosexual male sex worker. The later representations of male sex work in film also reflected a new gay sensibility about gay life in the United States. For example, both My Own Private Idaho (1991) and The Living End (1992) feature the reality of HIV/AIDS as part of the lives of male sex workers. Later works focused on the professional lives of male sex workers and their personal selves. Boy Culture (2006) featured an openly gay male escort who was seeking to form a long-term, monogamous relationship despite his involvement in the commercial sex industry.

These gay films better reflect the reality of modern male sex workers. While the most popular representations suggest that gigolos are common, they have never been a substantial fraction of the male sex worker market. In historical times and at present, male sex work, in the vast majority of cases, is a homosexual activity. Sex workers and clients are male and are selling and purchasing homosexual sex. Earlier scholarship has always noted this, but has tended to concentrate on sex work as a form of deviance (not necessarily for its homosexual orientation but due to its taboo nature and illegal status), or as a means to study psychological factors related to entry into sex work. With the advent of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, research concentrated on male sex work as a vector of transmission of sexually transmitted infections, where sex workers could spread disease.

While all of these scholarly goals are admirable, the reality of sex work as a market has been obscured. Neither in the past nor now is male sex work primarily about these factors. It is about the supply and demand for sexual services from a man by another man. That fact is reflected in the ways in which male sex work takes place – that is, how male sex workers secure clients and how clients choose between sex workers. Given that the gay male population is relatively small, sex work is better aided by technology than female sex work, as cities would have relatively small “street tracks” where male sex workers would congregate. Male sex workers needed to reach their client base (homosexually identified men), and as of the mid-twentieth century were using gay media to reach clients. Magazines and newspapers of the time regularly featured the advertisements of male sex workers in the back pages. There are examples of escort advertisements in the pages of the Bay Area Reporter, the San Francisco Bay Area’s local gay newspaper. The use of gay media was common in early sex work advertisements. It created the largest local market possible for male sex work services while also keeping the activity relatively discreet – clients would phone sex workers and arrange appointments. The earliest forms of communication provided coarse information for clients. Escorts typically listed a form of contact and a brief physical description, and, in many cases, the sexual services they offered to clients.22 There was one national magazine devoted to male sex worker advertisements, and it ceased publication only when male sex workers had cheaper options to secure clients.

The Internet changed the dynamics of male sex work entirely, in a manner similar to the transformation of gay society in general. While not fully supplanting the advertisements in local gay newspapers, the Internet allowed for easier entry and exit from the market, and the “feedback” features of the Internet allowed sex workers to establish reputations. The Internet has become the primary medium through which male sex workers secure clients. As the Internet has flourished, escorts have been able to distinguish themselves by creating online personas that were not possible in earlier modes of communication.23

The medium provided by the Internet allows the analysis of male sex work, for the first time, to fully embrace its economic underpinnings. Male sex work is not charity – it is a service provided by a seller to a buyer. For most of its history, however, we had little information about what was actually being provided and at what price the services were being sold. This is in contrast to female prostitution, where prices from a variety of sources have been known for some time.24 For historical periods, we have few sources for pricing of male sex work. Even in contemporary settings, the best estimates of the market price come from individual responses in work devoted to the experiences of a small number of sex workers.

For economic analysis this poses several problems. First, price variation in a market like male sex work could come from a variety of sources. Smaller samples of sex workers are usually confined to small geographic areas. Differences between sex workers, local market prices, and the substitutability of sex workers in markets can all play a role in the prices observed. Economic analysis of a market requires extensive information about the market. For nearly all economic analysis, this implies quantitative data. Measures of prices, quantities, product quality, firm size, and consumer characteristics are standard. Throughout this work, quantitative data will be emphasized, and the sources of that data are described below.

Second, sex workers themselves may be more or less willing to divulge their prices to surveyors. That is, the price information we have from surveys may be driven by selection, where only certain sex workers provide their prices. If this is related to other attributes (say, only sex workers who are successful and popular are willing to divulge their prices), we will be unable to describe the market in any detail. In other words, we would like the same price information that a consumer of male sex services would see. This would ensure that the analysis of the market is working from the same base of information that clients use.

This book exploits two primary sources of data to empirically analyze male sex work and its social and economic underpinnings. The first source of data is advertisement data for male sex workers. This is drawn from the largest and most comprehensive data on male sex workers in the United States. The advertisement data has been the key source for analysis of the market to-date. Since escorts post their prices publicly, the advertisement data gives a direct measure of prices, which differs from the usual approach of surveying or inferring prices.25 Inferring prices runs the risk of spurious correlation – prices may or may not be related to the factors that are assumed to be sources of price variation. The data used here comes from the universe of male sex workers advertising on the chosen website in the United States at the time of data collection. As such, these data represent the entire population.

Relative to other data sources, online advertisement data has several advantages. First, this data allows one to collect information on escorts’ attributes, prices, and information without regard to some of the selection problems that one would encounter in a survey of escorts. For example, escorts who charge very high (or very low) prices may not respond with accurate prices in a survey. Another concern would be that escorts in general would not report their typical price but, instead, the highest price they had ever charged. This would result in an average price that would be far above the prices actually charged. Second, escorts have one account on the website and may list themselves in multiple cities that they serve. Third, the escort characteristics are entered by escorts from dropdown menus; this is particularly advantageous for features one would like to control for in pricing models, such as body type or hair color, whereas free-form responses may be difficult to evaluate consistently or may be missing altogether. There are other sources that allow for free-form escort responses; these sources are not as comprehensive as the one used here. Fourth, the website is free for viewing by all: there is no charge or account required to view any advertisements, photos, or reviews of escorts.

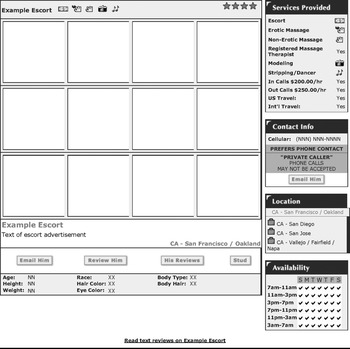

In particular, the advertisement data is a set of nearly 2,000 men from the largest and most comprehensive website for male sex workers in the United States. Beyond its geographic coverage, there is a rich amount of information that can be exploited to uncover more about male sex workers than before. Figure 1.1 shows a diagram of an escort advertisement. Escorts list their age, height, weight, race, hair color, eye color, body type, and body hair type. They give clients contact information and also their preferred mode of contact (phone or e-mail), their availability to travel, and their prices and availability for in-calls and out-calls. In-calls occur when a client travels to the escort; out-calls when an escort travels to the client. Escorts also provide clients with the range of services they offer in addition to escort work such as modeling, erotic massage, and stripping. Escorts have a simple table they can use to let clients know their weekly availability. There is also the actual text of the advertisement itself, which allows escorts to write about their services and quality. The largest piece of the advertisement is made up of the escort’s pictures, which are uploaded by the escort. These pictures may be of any feature of the escort that he chooses, and may be clothed or nude.26

Figure 1.1 Diagram of online escort advertisement

One unique feature of the advertisement data source is that it provides two types of reputation measures that come from clients. These are proxies for escort quality, which is an important component in any service such as male sex work. These are survey reviews (similar to feedback on eBay.com) and detailed reviews of escorts. The survey reviews ask the reviewer five questions about the escort (four of which are “Yes/No”) and a rating on a four-star scale.27 The detailed reviews, “text reviews,” are the detailed, free-form client reviews described earlier. In addition to providing a review of escort services, clients also give the date of their encounter with the escort, the type of appointment made (in-call, out-call, or an extended appointment such as an evening or weekend), and the price paid, which I term the “spot price,” as it reflects the price paid in a specific transaction.28 As noted earlier, a key advantage of these reputation measures is that escorts have no control over their reviews – all reviews of both types are retained if the escort allows reviews, not a selected sample that is posted or chosen by the escort. However, a key disadvantage to note is that anyone can post a review, including an escort, though this sort of thing is likely to make up only a small percentage of the reviews.

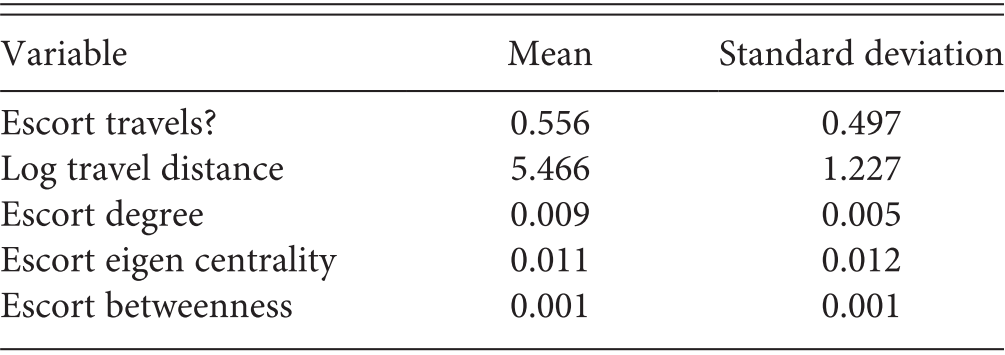

Table 1.1 shows the summary statistics for the escorts in the advertisement data. First, the data contains nearly 2,000 male sex workers who advertise online. This is a large number of sex workers, and at a minimum, it establishes that the number of participants in the market is substantial. Second, male sex work is well compensated. On average, escorts charge more than $200 an hour. This is consistent with other estimates of escort services, which are close to the $200-an-hour range.29 Escorts are reasonably fit – on average a male sex worker is 5 feet 10 inches tall and weigh around 165 pounds. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the average man aged 20–74 in the United States is 5 feet 9.5 inches tall and weighs 190 pounds, which implies that escorts are slightly taller and thinner than the average adult male in the United States.

Table 1.1 Summary statistics for the escort advertisement data sample

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. | Physical trait | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. | Behavior | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hair color | |||||||||||

| Price | 1,476 | 216.88 | 64.46 | Black | 1,932 | 0.37 | 0.48 | Top | 1,932 | 0.16 | 0.37 |

| Log of price | 1,476 | 5.34 | 0.29 | Blonde | 1,932 | 0.13 | 0.34 | Bottom | 1,932 | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| Weight | 1,932 | 167.11 | 24.54 | Brown | 1,932 | 0.46 | 0.50 | Versatile | 1,932 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| Height | 1,932 | 70.43 | 2.69 | Gray | 1,932 | 0.02 | 0.13 | Safer | 1,932 | 0.19 | 0.39 |

| BMI | 1,932 | 23.64 | 2.89 | Auburn/red | 1,932 | 0.01 | 0.11 | ||||

| Age | 1,932 | 28.20 | 6.93 | Other | 1,932 | 0.01 | 0.10 | ||||

| Asian | 1,932 | 0.01 | 0.12 | Eye color | |||||||

| Black | 1,932 | 0.22 | 0.41 | Black | 1,932 | 0.02 | 0.14 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1,932 | 0.14 | 0.35 | Blue | 1,932 | 0.18 | 0.39 | ||||

| Multiracial | 1,932 | 0.08 | 0.28 | Brown | 1,932 | 0.55 | 0.50 | ||||

| Other | 1,932 | 0.01 | 0.10 | Green | 1,932 | 0.11 | 0.31 | ||||

| White | 1,932 | 0.54 | 0.50 | Hazel | 1,932 | 0.14 | 0.35 | ||||

| Body hair | |||||||||||

| Hairy | 1,932 | 0.04 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| Moderately hairy | 1,932 | 0.30 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| Shaved | 1,932 | 0.17 | 0.38 | ||||||||

| Smooth | 1,932 | 0.49 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| Body build | |||||||||||

| Athletic/swimmer’s build | 1,932 | 0.48 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| Average | 1,932 | 0.13 | 0.34 | ||||||||

| A few extra pounds | 1,932 | 0.01 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Muscular | 1,932 | 0.30 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| Thin/lean | 1,932 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

Price is the out-call price posted by an escort in his advertisement.

See the data appendix for variable definitions.

The average male sex worker is 28 years old. While 28 is certainly young, it is a far departure from the young men described in historical accounts of male sex work. The median age of male sex workers in the data is 26.30 Escorts are also racially diverse: while more than half of all escorts are White, more than a fifth are Black and more than a tenth are Hispanic. Escorts in the data are racially diverse – 54 percent are White, 22 percent are Black, 14 percent are Hispanic, 8 percent are multiracial, and 1 percent are Asian.

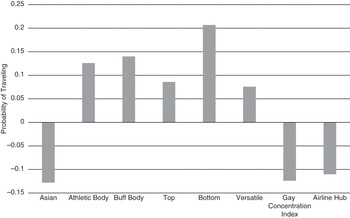

For physical traits, escorts are likely to have black (36 percent) or brown (46 percent) hair (fewer than 15 percent are blond). More than half of all escorts have brown eyes (55 percent), although significant fractions have blue (18 percent) and hazel (14 percent) eyes. Nearly half of all escorts are smooth (49 percent), and 17 percent shave their body hair, but more than a third are hairy or moderately hairy (34 percent). Very few escorts are overweight (1 percent), and relatively few are thin (8 percent); the majority of escorts claim to have athletic (48 percent) or muscular (30 percent) builds. For sexual behaviors, 16 percent of escorts offer penetration to clients (this is known as being a “top”), while 6 percent offer to be penetrated (and are known as “bottoms”), and 21 percent of escorts list themselves as “versatile.”31 In addition, 19 percent of escorts advertise that they exclusively practice safer sex. Overall, the summary statistics for the men in the data are similar to the descriptive statistics noted by Cameron et al. (Reference Cameron, Collins and Thew1999) for male escorts in British newspapers in the 1990s and Pruitt’s (Reference Pruitt2005) more recent sample of male escorts who advertise on the Internet.

Overall, this diversity points to there really being no “typical” male sex worker. They come in a variety of ages, races, physical appearances, and sexual behaviors. At one level, this is what we would expect from sex work. Clients could have demand for a variety of men, and this demand should lead a variety of men to supply sex work. At another level, this diversity reflects the fact that earlier descriptions of male sex work that make appeals to a monolithic experience are somewhat outdated to the extent that this diversity in male sex worker supply requires a more careful description of the men involved in sex work. Lastly, the compensation offered to male sex workers shows it to be a lucrative profession. At $200 per hour, a male sex worker who sees one client per day Monday to Friday would earn more than $50,000 per year. This is more than the median household income in the United States, and matches the median earnings of male college graduates in the United States.

The second data source comes from transaction-specific data from client reviews of escort services. The data come from the online reviews hosted by Daddy’s Reviews (www.daddysreviews.com), the oldest and most popular client-based forum for reviews and discussions of male sex workers. This website has been in existence since 1998 and provides a rich structure for clients to review male sex worker services. The website contains both a forum (message board) for clients to discuss male sex workers and a review feature where clients provide detailed reviews of their specific encounters with male sex workers. The individual reviews of male sex workers are the data used here. A key for this data is that all reviews of male sex workers are held in a holding tank and individually verified by the website administrator before they are posted. Male sex workers cannot remove reviews, and reviews are flagged if they are suspicious (for example, entered by a competing male sex worker or by the sex worker himself). As described by Logan (Reference Logan, Cunningham and Shah2016), Logan and Shah (Reference Logan and Shah2013) and discussed earlier, this website acts to police male sex workers, allowing clients to inform each other about the quality of male sex workers – and this function minimizes the opportunity for male sex workers to exploit clients. Logan and Shah (Reference Logan and Shah2013) also note that it is extremely difficult for a male sex worker to create new identities for himself, as clients track them over time using this source. When a male sex worker changes his location, over time all of his previous reviews are retained and linked to him, and the same is true if the male sex worker changes his professional name. Male sex workers who have retired are not removed from the website, but are listed as “retired.” Male sex workers do have the ability to post comments on reviews. Male sex worker reviews can be searched by individual male sex worker name or geographically.

For each male sex worker’s review page, the male sex worker’s contact information is listed as well as all reviews, which are listed in reverse chronological order (newest to oldest). Figure 1.2 shows an example of a client review on the website. (Because client free-form reviews are sexually explicit, that field is obscured in Figure 1.2.) Reviews were collected using a script that pulled the information from the website into a database organized by the fields in the advertisement. As the figure shows, reviews detail the date and location of the transaction, the length of the appointment, the price paid, the client’s perception of features of the escort (height, weight, age, etc.), and the sexual behaviors that took place in the given transaction.

Figure 1.2 Example of escort review

The reviews also allow for clients to enter free-form text that describes their encounter in more detail. This field is read manually and coded for sexual behaviors not categorized in the reviews. In addition, clients rate the experience. At the end of the review, clients identify themselves with a unique “handle” username. The total sample contains 6,269 transactions for 1,418 male sex workers in the United States over a 6-year period. Table 1.2 shows the summary statistics for the data. The majority of transactions (60 percent) are hourly appointments, and another 25 percent are less than 3 hours. Slightly more than a tenth of the appointments are of long duration (more than 4 hours).

Table 1.2 Summary statistics for the client reviewed transactions data sample

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transaction measures | |||

| Hourly rate* | 5,452 | 227.07 | 299.23 |

| 1-hour appt. | 6,269 | 0.59 | 0.48 |

| 90-min. appt. | 6,269 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 2-hour appt. | 6,269 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| 3-hour appt. | 6,269 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| 4-hour appt. | 6,269 | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| > 4-hour appt. | 6,269 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escort characteristics | |||

| Asian | 1,418 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Black | 1,418 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| White | 1,418 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Other race | 1,418 | 0.30 | 0.49 |

| Latino | 1,418 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| Endowment (in.) | 1,418 | 8.00 | 1.04 |

| Circumcised | 1,418 | 0.76 | 0.43 |

| Age 20s | 1,418 | 0.38 | 0.49 |

| Age 30s | 1,418 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| Age 40s | 1,418 | 0.05 | 0.22 |

| Age 50s | 1,418 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| BMI | 1,418 | 24.79 | 2.71 |

| (BMI)^2 | 1,418 | 621.87 | 140.82 |

| Height (cm) | 1,418 | 179.81 | 6.58 |

| Weight (kg) | 1,418 | 80.35 | 10.74 |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual behaviors | |||

| Versatile | 6,269 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| Top | 6,269 | 0.37 | 0.44 |

| Bottom | 6,269 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| No anal sex | 6,269 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Kissing | 6,269 | 0.62 | 0.49 |

| Masturbation, mutual | 6,269 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Masturbation, receives | 6,269 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| Masturbation, provides | 6,269 | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| No masturbation | 6,269 | 0.43 | 0.07 |

| No condom | 6,269 | 0.20 | 0.29 |

Note: Sexual behaviors are defined from the perspective of the escort.

* Hourly rate is defined for appointments lasting less than 4 hours.

“No condom” requires that the client noted penetration in the transaction.

For the transactions, I find that the average price of an hourly session is $227, consistent with other estimates of male sex worker services from escort advertisements and the advertisement data. As a check against the advertisement data, the basic features are quite comparable. In terms of escort characteristics, the largest proportion of male sex workers in the transaction data are White (49 percent), while a significant share are another race (30 percent). For age, nearly 40 percent of escorts are noted by clients to be in their twenties, and more than a quarter in their thirties (26 percent).

The transaction data establishes that male sex work does involve sex. In terms of sexual behaviors, 37 percent of transactions involved male sex workers penetrating clients, 17 percent involved clients penetrating sex workers, and 40 percent involved both client and male sex worker penetration. Only a small fraction of transactions, fewer than 5 percent, involved no penetration.

Other sexual details show that male sex work involves more than just sexual services, but extends to other intimate behavior. More than half (62 percent) of transactions involved kissing and more than half (54 percent) involved masturbation. In addition, 80 percent of transactions involved sex with condoms, which suggests that male sex work is nearly as likely to involve condoms as noncommercial gay sex.32 Overall, the summary statistics for the male subjects (age, race, height, weight, etc.) are similar to the descriptive statistics noted by Cameron et al. (Reference Cameron, Collins and Thew1999), Pruitt (Reference Pruitt2005), Logan (Reference Logan2010), and Logan (Reference Logan, Cunningham and Shah2016) in analysis of male sex worker advertisements. The behaviors described in the transactions are also consistent with the patterns seen in small-sample surveys of clients, such as those in Grov et al. (2013).

These two data sources give us information on both the supply and demand for male sex work services. The advertisements give us a rich set of information akin to that used in most market studies. From all comparisons, the data appears to be consistent with data from smaller samples, but is more diverse than the smaller samples in that it is national in scope and contains a more diverse range of men – racially, physically, and sexually. In addition, the availability of price information is particularly important as these two data sources are the largest available sources of information on the prices of male sex work in the United States. Since both data sources also contain additional personal and geographic measures, there are a number of additional items in advertisements and transactions that allow us to test whether there are significant price differentials that are driven by economic or social phenomena. Obtaining prices and detailed information for such a large illegal market is rare, and the recent criminal prosecution of male sex worker websites decreases the likelihood that this sort of analysis can be consistently performed into the future. Nevertheless, the remaining chapters of this book will investigate the present (and, perhaps, future) status of male sex work in the United States.

Male sex work presents a number of challenges for traditional market analysis. Despite its appearing online in a manner similar to that of other products in the age of the Internet, an economic approach to male sex work must begin with by considering several preliminaries that we usually neglect in economic analysis because we can safely assume them away. For example, in a traditional market we are not usually worried about whether prices in the market accurately reflect equilibrium prices – the point where producer supply and consumer demand intersect. When we observe a price in an online marketplace we take that to mean that the firm is choosing the price to maximize profit, and implicitly assume that the maximization takes into account consumer demand for the good.

If the prices in the market do not reflect underlying economic principles, it is difficult to know how this market operates, or if it operates at all. A traditional supply-and-demand approach would be inappropriate if observed prices had little relationship to economic primitives. The illicit nature of the transactions in male sex work make it difficult to argue that the market “gets prices right” simply because they are publically posted online. After all, in what other illegal market are the prices of goods and services openly displayed? The basic tenets of market analysis require that we first confirm that the prices in the market reflect underlying fundamentals about consumer and producer behavior. The first question to answer is the most basic: Does this market work? (And if so, how does it work?)

To answer this question, we must step back and think more abstractly about what a sex worker transaction is. At its most basic level, sex work is a contract. Whether purchasing gasoline, a candy bar, or a home, transactions are contracts. A good or service is sold at a specific price offered by a seller to a buyer at a specific place and time. The contract does not have to be formal or written, and the law acknowledges that most contracts are informal ones whose terms are implied by the context of the transaction itself. Payment terms are stipulated and our legal system enforces these contracts if they are disputed. This helps both buyers and sellers – if the good or service is not delivered as advertised, or if payment is not received, either party can turn to the courts to have the contract enforced.

If a consumer were purchasing shoes from an online retailer, for example, the customer would be confident that the product he or she ordered would be the product they would receive. If this turned out not to be the case, they could resort to a payment service, the vendor, or even the courts if they were duped and either sold a different product or received nothing. In other words, they would buy with confidence – if not confidence in the seller, than certainly confidence in a system that would enforce or void their contract, depending on the situation. The same applies for the seller. For that reason, analysis of the market would proceed with an understanding that both buyers and sellers are acting with full faith that their transactions will be completed. The analysis of markets usually presumes that contracts will be enforced.

In an illegal market such as male sex work this presumption does not hold. Courts will not aid those seeking to enforce contracts for illegal acts. This poses a problem for market analysis of male sex work because we cannot assume that buyers and sellers are acting with any confidence that their transactions will be enforced. We therefore lose confidence that what we observe from the illegal market is what actually occurs. In other words, we need to first check that the prices we observe from these online sources are plausibly related to actual transactions.

In addition to formal enforcement, information is also critically important in markets. Economists have long recognized that information exchanged between buyers and sellers helps to ensure that more transactions will take place. Even with contract enforcement, it is still possible that information will improve market function, lead to more transactions, and increase consumer welfare. In the classic example, if a seller offers a used car for a certain price, any reasonable buyer would have to fear that the car may be worth (much) less than the advertised price. Unless the seller can provide additional information about the car’s quality or offer a guarantee, it is unlikely that a buyer will be found at the price advertised. In this case, the seller has more information than the buyer, and a smart buyer will realize this and naturally fear that he or she can be duped by the seller. This case of asymmetric information can stop transactions before they start. In the most extreme case, no buyer will be found.1

Even when there is contract enforcement, buyers and sellers would rather not use them. Contract enforcement is costly in both time and money, and buyers will rightly be wary of sellers whom they do not trust. The seller must therefore provide a great deal of information to the buyer in order for the transaction to take place. As such, information helps to make transactions possible because they build trust between a buyer and seller. The market can and does take information into account, and the more objective the information the better. One reason this information can be taken into account is because it, too, is an implicit part of the transaction.

Male sex work does not necessarily have this market structure. While the information structure of the online market is quite rich, the transactions themselves are completely illegal. This is the reason the Department of Homeland Security moved to close Rentboy.com in 2015 – the federal government argued that the website was facilitating prostitution through the website, even though the website did not profit from transactions. Every transaction that takes place within male sex work is done with full knowledge that any agreements between sex worker and client cannot be enforced. For economic analysis, this creates a serious problem. Formal enforcement is often seen as the cornerstone of contracts. While information can overcome the problems of asymmetric information, this assumes that the information provided is credible and verifiable, which is made more likely when contracts can be enforced.2 At a minimum, if the information were false economists assume that there would be a means of redress for fraud. While the use of formal institutions such as courts is rare relative to the volume of transactions, the standard argument is that the presence of formal institutions gives contracts their authority and information its credibility. In Schelling’s classic terminology, “the power to sue and be sued” gives parties the ability to make credible exchanges of information and enforceable commitments, a prerequisite to most transactions.3

Without any means of redress, the information that buyers and sellers share would have little value. Since there would be no punishment for misrepresentation, a reasonable consumer would heavily discount all promises made by sellers. With no recourse for fraud, gross misrepresentation, or failure to provide the service, the market might not exist at all – no buyer would trust any of the information provided by a seller, and honest sellers would not be able to distinguish themselves from fraudulent ones. This implies that what we see online is an illusion with little connection to the actual practice of male sex work.

This is not to say that economists are naïve and always assume that formal enforcement is necessary or available. There are many transactions that take place without formal enforcement, and some that do not require the presence of formal enforcement. Numerous studies have documented how informal networks, long-term relationships, and reputations overcome problems of asymmetric information. Indeed, researchers have developed large literatures that look at limited contractibility and situations where formal enforcement is costly, as a way to consider the additional mechanisms that must be in place if existing institutions are lacking or unable to settle disputes.4 The literature has not developed an empirical answer to whether the value of information without formal enforcement approaches its value when formal enforcement is present, however.

This question matters a great deal for the study of the market for male sex work. Without an answer to this question it is not clear that this market behaves in a way that can be described by traditional economic theory. There is information transmitted in the market, but the question is whether (and how) it is valued. In most illegal markets this is not a problem because the good exchanged (say, narcotics) is done in a face-to-face process. Reputations, networks, and relationships are key in most illegal markets, and prices are private and negotiated directly between buyer and seller. In the modern world for male sex work, however, this is not so. Male escorts are not hired off of the street. Rather, they are selected online in a highly impersonal process. There are few escort agencies that could act to vouch for a sex worker – the websites simply host advertisements. Reputations established online could be entirely false. Men enter the market regularly, and new entrants need to be able to establish themselves in the industry like any other service provider, but there are few ways to do this in an illegal market. Most important, every client knows this to be the case.

The question, “Does this market work?” is therefore actually two related questions: Are formal enforcement mechanisms necessary in order for the information that male sex workers and clients share to have value? And if not, what is the value of information in this environment without formal enforcement? These questions are refinements of the basic question asked before, and get to the heart of the issue – in order to study the market for male sex work in a traditional way, we first need to know whether the market functions like a traditional market. In traditional markets, information has value, and if the information in this market has no value, then it is unlikely that the prices and quantities correspond to what we would assume in traditional supply and demand analysis.

The problem is most illegal markets have coarse information environments. Take the example of illegal narcotics. It is rare that someone looking to purchase drugs can choose between several sellers the way that someone shopping for a book would. Most illegal markets are also highly secretive and heavily dependent on personal connections. Unlike regulated businesses, illegal markets work by word of mouth and knowledge of the goods and services being provided is not usually in plain view. In these markets, reputations and networks operate to ensure that transactions take place. Given the types of networks, it is challenging to obtain information on prices, quantities, and consumer and producer behavior, making empirical answers to these questions especially difficult. The online market for male sex work must overcome the problems posed by asymmetric information but in an impersonal manner for an illegal service, a very tall order.

So, then, how does this market work? Does it get prices right? In this chapter, I show how the male sex work market leverages high technology and a rich information structure to make this market work. I begin by documenting the ways in which the clients of male sex workers informally police the market: by informing other clients of deceptive sex workers and by reviewing sex workers on independent, client-owned websites. The informal policing in the market is critically important and allows this market to function. In economic terms, the policing raises the cost of misrepresentation for would-be fraudulent escorts and simultaneously rewards the truthful self-disclosure of honest escorts. This acts to encourage credible escorts to enter or remain in the market and to prevent fraudulent escorts from entering or persisting in the market. In an illegal market such as male sex work this policing works as one of the only means of enforcement, and it is entirely informal.

I exploit this institutional knowledge further to identify the specific information clients treat as a signal of escort quality. Both clients and escorts explicitly mention face pictures in discussions of escort credibility and misrepresentation. Using narrative evidence from qualitative studies, news reports, and online forums, I show that clients look for face pictures in an escort’s advertisement as a sign that the escort is trustworthy. Being mentioned as the signal of escort trustworthiness is one thing, though, and whether the market values that information is another. If this market is well functioning, the signal of quality should have value.

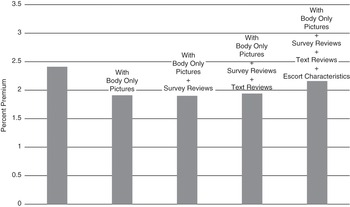

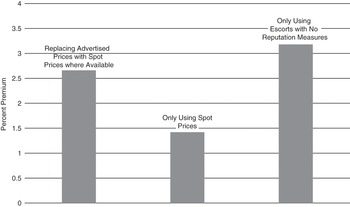

The market values face pictures, and escorts who post face pictures are able to earn 11 percent more than escorts who do not, on average. In dollar terms, this would be in excess of an additional $10,000 per year in earnings. Spot prices – specific transaction prices recorded by clients – independently confirm the estimates from advertised prices. This is important because spot prices are prices we know that clients actually paid, which could be different from the prices that have been advertised. Consistent with the institutional analysis, I find that escorts who post pictures of their faces receive a sizable price premium: twice the premium to that on pictures in general. Indeed, the premium that accrues to pictures is actually completely attributable to face pictures.

This finding is robust with regard to a number of considerations. First, it holds when looking at escorts who have no reputation measures in their advertisements. This implies that new entrants to the market understand the value of face pictures, and price their services accordingly. Second, the premium holds when looking at spot prices only. This means that the premium is not an artifact of escorts with face pictures simply posting higher prices than others – clients actually do pay more for the services of escorts who post their face pictures. Third, I find that the premium is not driven by beauty. It could certainly be the case that only attractive escorts show pictures of their faces, and this would mean that the value of face pictures is not about information in an abstract sense but about the physical features revealed in face pictures. I find that the premium remains even when controlling for the physical beauty of the male escort.

Male sex workers and their clients successfully overcome the problem of asymmetric information in an illegal market. I show how this market functions without formal enforcement, describing how clients police the market and identify the specific information consumers take as the signal of quality in this market. Interestingly, the per-picture price premium I estimate, 1.7 percent, is similar to the per-picture premium observed for used automobiles on eBay.com.5 Irrespective of the reputational concerns of escorts, I document how client policing can increase the costs of doing business for low-quality escorts. Increasing their cost is one of the primary ways of minimizing their numbers. While previous empirical work looks at how information technology improves market function, I provide the first evidence that an illegal online market is quite responsive to information, even when it cannot be verified or where misrepresentations cannot be punished.6

The market for male sex work provides a case where the richness of the information environment overcomes some of the problems of asymmetric information. The illegality of the market and the near-impossibility of guaranteeing truthful disclosure imply that the market should disappear or be a market where information has dubious value. However, I find that clients informally police the market, successfully punishing misrepresentation and rewarding credible escorts. This enables male escorts to signal their quality and allows prices in the market to respond accordingly. Despite its being an illegal market, male sex work exploits high technology to ensure that the market functions well. The answer to the question, “Does this market work?” is, despite obstacles generally presented by illegal markets, “Yes.”

The Online Market for Male Escort Services

The male sex work market now largely takes place online.7 Although female sex work has recently begun to appear online in Internet forums such as Craigslist.com, male escorts have had access to large and profitable websites devoted to the male sex trade for well over 15 years.8 Unlike escort agencies and other online, two-party transactions such as eBay.com purchases, the websites themselves do not derive any profits from the transactions escorts conduct with clients; they simply allow escorts to post their advertisements and contact information. The websites charge a set fee to escorts for hosting an advertisement and act as a clearinghouse where escorts advertise their services and clients choose between escorts. Consequently, these sites do not screen clients for escorts or vice versa, make no claims or guarantees about the quality of the escorts, and offer no recourse to clients in cases of poor escort performance or fraud.

The large number of male escorts and their ability to price directly without intermediaries create a market setting similar to others that are compatible with competitive market assumptions.9 Competitive markets generally rest on relatively simple criteria: many buyers and sellers, free entry and exit of sellers, the same good or service is sold by all sellers, and buyers and sellers have the same information. Under these conditions we expect markets to function well. Since this market is an illegal market, however, there is a potential for escorts to mislead clients and engage in fraud. In particular, an escort’s ability to post unreliable information and to misrepresent himself should lead to adverse selection in the market. The adverse selection here would be one where fraudulent male escorts would be the predominant actors in the market.

While escort claims are verifiable ex post, there are no formal institutional penalties for ex ante misrepresentation. Similarly, it is unclear how much weight a reputation in an illegal online market carries, and whether any client would respond to claims of high-quality service. Without formal enforcement and with the stakes particularly high (especially for men who are married or not generally assumed to partake in homosexual behavior), it is unclear whether a rich information environment alone can prevent the adverse selection described above. Previous research based on newspaper advertisements for male escorts found no differences in pricing due to information.10 Since the market has moved online, however, there are more service providers and more likely clients than before. The open question is whether the rich information environment offered by the Internet increases opportunities for escorts to disclose information about themselves, which could signal their trustworthiness, and whether the pricing of male escort services is related to this information.

The market for escort services is one of the few instances where illegal behavior is openly advertised. While this is extremely rare for illegal markets, there are reasons why escorts publicly announce their prices for services. First, and somewhat counterintuitively, is that it minimizes the legal risks of sex work. In most police stings for solicitation, the sex worker and the client must agree to both a price and sexual conduct. In order to be prosecuted for prostitution the illegal contract must specify, verbally or otherwise, the terms of the transaction. By posting prices and sexual behaviors online, clients and escorts obviate the need to discuss payment, prices, and sexual behaviors at the same time. In fact, escorts are wary of clients who discuss prices, as this is taken as evidence that they could be police officers.11 In fact, how-to guides for clients and escorts advise both to keep contractual discussions to a minimum:

Understand, though, that they might not be able to fully describe over the phone what they do because they don’t want to get busted … Most escorts will not discuss specific sexual acts for sale. Such is illegal and their services are for time and companionship only. Money is exchanged for time only, the decision to have sex would be a mutual and consensual decision two adults make. Upon meeting the escort, you may be asked certain questions about any possible affiliation with law enforcement.12

Second, escorts compete with one another on these websites. While clients calling a traditional escort agency can be steered to a particular sex worker, clients of male escorts can freely choose between hundreds of options. This is close to the assumption of a market with many sellers. In such a market, clients may be unwilling to engage escorts who do not post their prices or who appear to be less forthcoming about the services they offer, especially if their competitors are forthcoming. Some qualitative interviews with escorts have revealed that escorts post prices as a way to ensure that clients who contact them can afford their services.13

Third, by setting their prices publicly, escorts avoid the time otherwise spent haggling with clients over prices, a staple of street prostitution.14 Escorts assume that any client contacting them knows their price and will pay the posted rate for services, just as any other business owner would expect customers to pay the advertised rate. While the online advertisement sites are clear that money is not exchanged for sex and is only compensation for an escort’s time, the value of that time is not subject to negotiation, either. Despite this publicly posted information about illegal activity, police raids of online male escorts are surprisingly rare.

There are several sources that describe the generic male escort encounter.15 Clients contact escorts directly and arrange for appointments either at the home of the escort (an “incall”) or at the home or hotel of the client (an “outcall”). In the most basic form of an outcall, a client will search escort advertisements and choose an escort. If an appointment is immediately desired, such as the same day, the client will usually phone the escort. Appointments for future dates may be arranged by e-mail, although some escorts prefer to make all appointments by phone. Escorts generally encourage clients to describe the length of the desired appointment and to note any circumstances of which the escort should be aware (e.g., manner of dress required by client and clients who may be disabled). Escort and client then discuss the time and location of the appointment. Once the escort arrives at the location, he meets the client and the two may have a brief discussion to reaffirm the earlier phone conversation. Payment is almost never discussed face-to-face. Money is usually exchanged after the appointment ends, but clients are encouraged to place the money in plain view, such as on a dresser or desk, either before the escort arrives or at the beginning of the appointment.

Interestingly, one reason the street market may be preferred to the online market, from a client perspective, is that misrepresentation would be rare. On the street, a client can see the available sex workers and choose one after negotiation. The problem is that the client can only choose from the escorts available at the time he is looking – he cannot schedule a future meeting nor can he see all of the available sex workers. Itiel (Reference Itiel1998) notes that male escorts and clients have less leeway to informally penalize misrepresentation than street sex workers and their clients. While street sex workers and clients can freely disengage from a transaction for whatever reason by simply walking away, the clandestine nature of an “incall” or “outcall” makes it difficult for either party to escape penalty free if there has been any misrepresentation. For example, once the escort has arrived at the hotel door or home of a client, it may be difficult to induce him to leave without payment of some sort. Also, once the misrepresentation is revealed, the client (and potentially the escort) is already exposed: the escort knows the client’s location, almost certainly some form of contact information, and the client may be open to blackmail and harassment depending on his circumstances. Moreover, clients cannot appeal to an intermediary’s reputation to minimize their exposure. There is no pimp, madam, or escort agency acting as a guarantor. The very nature of the male sex market alters the usual interpretation of the risks involved in sex work. While male escorts are seen as a “safer bet” than male street sex workers, the overall structure in the market is one in which the client is at risk of harm.16

Unlike female sex workers, who are at greater risk of being violated by clients, male sex workers are more prone to violate their clients. Clients are at risk in a number of ways, and the harm from hiring an unsavory escort can have serious consequences. First, escorts may simply rob clients; a traditional scam is to request payment up front and then feign an excuse to leave, never to return. Another common ploy is to steal the client’s wallet in the course of an appointment. In online forums, by far the most frequent complaint from clients is that escorts take payment but do not deliver services.

Second, an escort may blackmail a client or expose his client’s sexual behaviors. As noted earlier, clients and escorts usually communicate by way of telephone or e-mail before the appointment. Most escorts refuse calls from clients who have a “blocked” phone number, and this exposes clients to a risk of blackmail because escorts can trace the client’s phone number. Escorts could threaten to “out” a client, to inform his family of his sexual practices, to contact his employer, or even to contact legal authorities, since the client has solicited prostitution. The case of Ted Haggard (the former president of the National Association of Evangelicals, who became embroiled in a sex scandal involving a male escort in 2006) is one in which the escort kept voicemail messages from the client and later released them to the press. The additional social stigma attached to being exposed as a homosexual, particularly for men who hold positions of power in conservative religious or political organizations, can be career ending.

Several prominent political careers have been damaged by allegations of involvement with male sex workers.17 In addition to the well-publicized national cases, local politicians have also been exposed. In 2003, Utah State Representative Brent Parker (R) resigned when accused of soliciting an undercover police officer. In 2006, Tom Malin lost a Democratic primary bid for the Texas State Legislature when it was revealed that he had formerly been an escort.

Finally, since escorts are relatively young and virile men, physical violence is not uncommon. While escorts usually have someone they will keep abreast of the location and contact information for every appointment in case of an emergency, clients are less likely to let others know of their whereabouts, leaving themselves particularly vulnerable.18 In online forums, clients themselves mention instances in which escorts either attacked them or threatened them with bodily harm. Clients describe being punched, kicked, threatened or attacked with knives, guns, and other deadly weapons. For example, one client noted “The time an escort grabbed me by the throat and slammed me up against wall rifling my pockets for my wallet. Then punched me a couple of times for not bringing my ATM and credit card.”19 Moreover, these crimes are likely to be unreported, since the client would be forced to reveal how he came to know the escort in question.

Unlike the markets for other services, where clients may not choose to pursue legal redress for small matters, clients of male escorts do not have the option of seeking redress for any grievance, regardless of size. While one may be compensated in-kind for poor service at a restaurant, for example, there is no evidence of similar arrangements in the male escort market, even for relatively petty grievances. Escorts are not known to offer compensation or in kind services to dissatisfied clients.

The dangers that clients face increase their incentive to police the market. Without some form of policing, the market would be difficult for clients to navigate. Even with policing by clients, there are limits to how effectively an illegal market can be policed. Even in well-functioning online markets there are fraudulent sellers, and online services spend a great deal of time screening sellers. In the next section, I show exactly how clients informally police the market to minimize the probability that they will hire an unscrupulous escort.

Evidence from the Demand Side of the Male Escort Market

Informal Enforcement in the Male Escort Market

Why would clients be driven to police the market for male escort services? While policing helps the market to function, it comes at a cost to individual clients that benefits not only themselves but also clients who do not police the market. The precise motivations behind client policing are difficult to ascertain. The clients active in policing are providing a service to the market that enhances its ability to operate. It may be due to egalitarian feelings, a desire to protect others, or knowledge that their activities are critical to a market they are eager to be active in.

When a firm discloses information it is inherently making a promise to the consumer. Theoretically, in order for the signals that escorts send to be informative, there must be a reasonable basis for the client to trust the accuracy of the signal.20 Most economic models of signaling assume that signaling is truthful and that misrepresentation does not exist. In these types of models, when an escort signals, his sending a signal acts as a commitment device.21

The key issue when misrepresentation is forbidden is whether to disclose information at all, since the information must be truthful. This issue is pertinent for firms that would expose themselves to significant liability if they were to knowingly mislead consumers. In an illegal market, however, such guarantees cannot be made and informal policing may be the only option. Clients may police the market because they have little choice if they would like to minimize the probability of dealing with a deceptive escort. Since the websites that host advertisements for male escorts derive no income from clients and maximize profits by hosting the largest number of advertisements, they pay little attention to clients’ complaints about deceptive escorts who advertise on the websites. Interestingly, one client framed the situation in the classic used-car reference familiar to most economists:

That site is an advertising site, not an agency. If the used car you buy turns out to be a lemon, do you take it up with the paper that ran the classified ad for it? Could you imagine what managing that he said/he said would be like?

Just as the purchaser of a car advertised in the newspaper does not hold the newspaper responsible for the car being a lemon, clients of escorts cannot hold the website responsible for hosting advertisements of escorts who turn out to be fraudulent, dangerous, or deceptive.22