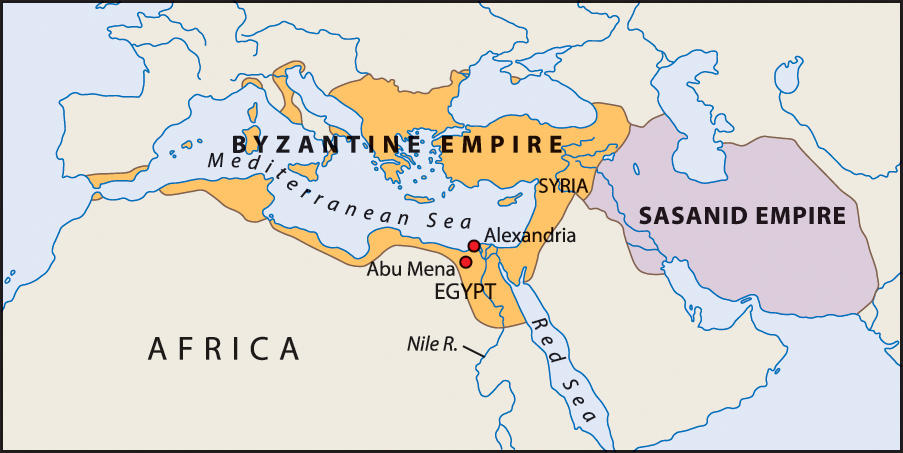

Manufactured at a local Egyptian workshop in the sixth or seventh century, this pilgrim’s flask, or ampulla, subtly reveals the militaristic world of its place and time. Saint Menas (d.c.300) was, according to his Passio, or martyrdom account, an Egyptian by birth. A soldier in the Roman army, he was put to death for his faith during the persecutions of Emperor Diocletian and brought to his burial place at Abu Mena, near Alexandria, Egypt, by camels. This explains why Menas here appears to be dressed in military garb. Surrounded by a circle of dots, he stands in the early Christian pose of prayer, hands raised to God, two Greek crosses flanking his head, and two camels kneeling at his feet on either side. The emphasis on camels is important: miraculously, the animals stopped at Abu Mena of their own accord and refused to move the body of the saint any further. The image is repeated on the other side of the flask. The vessel is far from being unusual: numerous flasks like this one were sold to pilgrims arriving at Abu Mena from all across the Christian world.

Egypt, c. 600.

When Menas was martyred, Christianity was a minority religion. But, later in the fourth century, when it became the official religion of the Roman Empire, Menas proved to be an extremely popular saint. One of the earliest churches in Constantinople was built in his honor. Pilgrims flocked to the modest shrine built over his grave at Abu Mena, and in the fifth century, Emperor Zeno (d.491) sponsored the construction of a grand complex there. Eventually, it included the Martyr Church, later enlarged; another, bigger church built to the east of the first one and connected to it; arcaded streets; and many buildings ranging from a grand palace to baths to modest shelters for the poor. To the south was a semi-circular building probably used as a hospital. In the early seventh century, Sophronius, the patriarch of Jerusalem, had good reason to describe the site as “the pride of all Libya.” It was one of the best-known Late Antique pilgrimage spots.

Pilgrimage was integral to the Christian experience in every way. In the early fifth century, Augustine, the North African bishop of Hippo, famously wrote that the very life of the Christian was a pilgrimage. Born into the City of Man, the believer made use of its institutions not to pursue a career or for pleasure or to make money. Rather, the “things of the world”—food, clothing, languages, schools—were to be “used” on life’s pilgrimage to the City of God, where peace, friendship, and happiness reigned eternally. The intercession of saints like Menas helped people on this arduous journey to the heavenly city. Saints could intercede with God on behalf of supplicants, especially of those who made an effort to trek to the shrine and make their petition. But this was not easy. By the seventh century, the famous Roman road system was in disrepair and highway robbery was common. Indeed, the hardships of pilgrimage were considered the necessary preparation for access to a holy relic: the effort expended on travel was a sure way to convince a saint of one’s true devotion.

What sort of help did Menas give the faithful? Stories about his posthumous miracles, recorded in the seventh and later centuries, were written in several languages, including Coptic, Ethiopian, and Greek. They tell vivid tales of Menas’s healings, conversions, and even how he brought about a resurrection from the dead. One amusing story recounts that while at the shrine, a crippled man is encouraged by the saint to climb into bed with a mute woman; the woman awakens screaming, the man flees swiftly in shame; at once they understand that they have been healed of their afflictions. Sometimes, Menas took instant revenge on wrongdoers. In one story, a man who comes to pray to the saint is hacked to pieces by a murderer who covets his gold, only to have Menas appear, revive the dismembered man, and punish the transgressor. Another miracle claims that a woman who was nearly raped by a stranger on her way to the shrine was saved when the saint caused the would-be rapist’s horse to drag him to the crowded shrine, where he was shamed before a jeering audience. Still another miracle suggests that in some parts of the early seventh-century Byzantine Empire, Jews were still seen in a positive way, as a people ready for conversion: that story has Menas come to the rescue of an honest Jew who is swindled by his dishonest Christian friend. The Christian seeks forgiveness, and the Jew decides to be baptized. There was, in fact, a baptistery just to the west of the mausoleum housing the tomb of Saint Menas. It had two separate rooms, one probably reserved for the baptism of women, the other for men.

The arrival at the tomb of Saint Menas was carefully orchestrated. In order to reach the shrine, all the pilgrims were obliged to follow a wide, colonnaded avenue that narrowed dramatically until it met a large rectangular space lined with porticoes and shops. Once at the saint’s mausoleum, the pilgrim still had to navigate a steep stairway as well as the dark and circuitous underground passageway to the crypt. But that made the goal all the more welcome. In the vicinity of the tomb, the pilgrim would have seen a stone relief carving of Saint Menas—probably the model for the design on this and other flasks, which were sold by vendors near the shrine. Then, entering the crypt, the petitioner would have arrived at the tomb itself, framed by a hanging dome covered in a gold mosaic that sparkled in the light shed by oil-burning lamps. The shrine’s guardian, an archpriest, led the pilgrim to the tomb to experience the “kiss” of the saint, symbolized by a bit of oil from one of the lamps. Many pilgrims planned to stay a night or two by the tomb, a period of “incubation,” to be sure that the saint would indeed intervene on their behalf.

Before returning home, the faithful filled the flasks with some substance sanctified by the mere proximity to the revered body: a handful of earth from around the shrine, water from a nearby spring, a bit of oil from the lamps that burned by the tomb or from an alabaster vessel that stood in front of the church altar. The ampulla was then sealed with a stopper that in some cases may also have borne the image of the saint. At some shrines, oil or water was poured through special openings over the holy relics and then collected at another opening, at the bottom, to be stored in flasks. Believers returned from pious pilgrimages wearing the ampullas at their belts or around their necks. Such objects had become eulogiae or “blessings”—and, indeed, some of them were inscribed with the word “blessing” or “gift.”

Gifts, indeed, were important for the devout. Pilgrims sought to extend their connection to the saints well after they returned home. Often, they left votive offerings (ex-votos) at the shrines, both in gratitude for the effected cure and in the hope that their virtual presence would continue to assure the saint’s assistance. The flasks, too, prolonged the pilgrims’ bond with the sacred places they visited, allowing the faithful to recall and re-live their pilgrimage spiritually. No wonder the devout were sometimes buried with their flasks. These objects were far more than souvenirs: they were bits of heaven to take home, expressions of hope that the pilgrim’s journey through life would end safely in the City of God.