I. Introduction: A Gold Mine Owns Up at Last

In Valunia chiefdom, in southern Sierra Leone, Cluff Gold Company mined for fifteen years without paying rent or compensation to the communities whose land it was using. Every time people complained, company officials claimed they were “only doing mineral exploration, not actively mining gold.” The paramount chief and a few elders visited the mining ministry office in Bo, the district capital, several times, but they were always told to go and come back.

When a paralegal named Prince Wudie began to work in Valunia, residents asked if he could help them take on Cluff Gold. Prince explained that Sierra Leone’s mining law was consistent with what the community knew intuitively: a mining company must pay surface rent to its hosts. Prince and chiefdom leaders initially tried to reach out to the company directly, but company officials refused to meet.

Prince and several community representatives also returned to the mining authority in Bo, but they too were told to go and come back. They then took a trip to Freetown and, with the help of the director of Prince’s organization, presented their case at the national directorate of the Ministry. The official in Freetown responded that the company was clearly in breach. He wrote to the firm, stating that its mining license was at risk if it could not come to an agreement with the people of Valunia.

Staff from the company told Prince they were willing to talk. The negotiation involved meetings with large numbers of community members, to hear their grievances and desires, as well as smaller discussions between company officials and Valunia’s chiefdom administration. The process took eight months. Ultimately, all sides agreed to a written agreement that stipulated, among other things:

An annual payment of surface rent to landowning families of up to 150,000,000 SLL (US$46,875) with a 3 percent increase every year during the life of the lease.

Backlog payment of surface rent for the previous eight years.

The construction of water wells and latrines for communities in the mining lease area.

Improvement on the main road linking the chiefdom headquarter town and other major towns.

Preference for employment of local youths in both skilled and unskilled jobs.

This was not a perfect solution. The company committed to paying eight years of back rent, for example, rather than the fifteen it owed. And the agreement did not include environmental protections. But after years of impunity, it was a meaningful step toward justice. The communities asked Prince to help monitor implementation of the agreement going forward. An elder who was active throughout the process said, in Sierra Leonean Krio:

If den man yah nor bin put wi en di company pipul den togeda, wi nor bin fo get dis wan word, en wi nor bin for benefit tay di company comot na yah.

If the paralegals did not bring us and the company management together, we would never have found this common ground, and the company would have finished mining and left this place without us benefiting.

Community paralegals emerged in Sierra Leone after the end of an eleven-year civil war as a way of providing basic access to justice and repairing the ties between citizens and state. The first paralegal organization, Timap for Justice, was founded in 2003, drawing explicitly on the long experience of community paralegals in South Africa. Since then, several groups have deployed paralegals, together serving as much as 40 percent of the population. In 2012 the government adopted a legal aid law that recognizes the role paralegals play in delivering justice services and calls for a paralegal in every chiefdom of the country.

This chapter aims to illuminate the experience of paralegals to date and the outlook for their work going forward. We start with a brief history of paralegal efforts in the country. Next, we present data from case-tracking research we conducted with three organizations deploying paralegals. We then draw on that data, as well as interviews with key actors, to explore the nature of paralegal efforts in Sierra Leone. We discuss the kinds of cases paralegals take on, how paralegals work, how they interact with the state, and how they’re funded. We close with a reflection on the role of paralegals in deepening Sierra Leonean democracy.

II. Paralegals in Sierra Leone, From Post-conflict to Post-Ebola

Between 1991 and 2002 some 50,000 people – 1 out of every 100 Sierra Leoneans, most of them civilians – were killed in a brutal civil war. A rebel faction called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) started the conflict by challenging Sierra Leone’s weak army in the east. Eventually the RUF captured the capital Freetown in 1997 in partnership with a group of disgruntled army officers called the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council. The war was characterized more by attacks on civilians than by conflict between combatants. West African regional forces, the United Nations, and the British military all intervened over the next several years, finally leading to peace under a civilian government in 2002.

Among the root causes of the conflict were arbitrariness in government and maladministration of justice.Footnote 2 The Special Court for Sierra Leone was established in 2002 for retrospective accountability – to try those most responsible for crimes against humanity during the war. At the same time several civil society groups expressed a desire to improve accountability going forward, by helping people who face injustice in their daily lives.

A coalition called the National Forum for Human Rights received seed funding for this purpose from an international organization, the Open Society Justice Initiative. A young Sierra Leonean lawyer, Simeon Koroma, and one of us, Vivek Maru, served as founding directors.

It was an open question what legal aid would look like. Sierra Leone has a dualist legal system. The formal system based on British law is concentrated in the capital. In 2003 there were 100 lawyers in the country total, and more than ninety of those lived in Freetown. A “customary” system, including “local courts” in each chiefdom, and lower chiefs’ courts that operate illegally, handle the majority of disputes. These institutions apply customary law, which varies by region and tribe and is uncodified. Lawyers have no standing in customary courts.Footnote 3

So a lawyer-based model of legal aid would have been unworkable. Instead, drawing on the experience in South Africa, the coalition proposed to experiment with a paralegal approach. It was thought that paralegals could work closely with communities, and engage customary and formal institutions alike. At the outset Koroma and Maru recruited thirteen paralegals – two in Freetown, and the others from five out of Sierra Leone’s 149 chiefdoms. Initial training focused on basic Sierra Leonean law, the structure and procedures of Sierra Leonean institutions, and skills like fact-finding, mediation, organizing, and advocacy.Footnote 4

In contrast to the way lawyers typically treat clients – as victims requiring a technical service – the paralegals sought to advance “legal empowerment”: to bolster the knowledge and agency of the people with whom they work. Not “I’ll solve it for you,” but “we’ll solve it together.”Footnote 5

In 2005, this effort became an independent Sierra Leonean organization called Timap for Justice. Timap means “stand up” in Krio. According to Daniel Sesay, one of the original paralegals, “When we began, we had no recipe for … how paralegals could address any of the myriad and complex injustices that Sierra Leoneans face.”Footnote 6 Paralegals developed methods through trial and error, by taking on real cases. Over time, they built relationships with local leaders and government officials. In a small number of severe cases, Simeon Koroma took formal action in the courts. Sesay writes, “We made this road by walking.”Footnote 7

In the years after the war several other groups besides Timap began to deploy community paralegals. The Catholic Church founded the Access to Justice Project in the Northern Province in 2005, for example, with a focus on survivors of sexual violence.Footnote 8 Another group, Advocaid, started in 2006; its paralegals and lawyers assist women in prison. In 2007, Timap itself doubled in size, growing to serve ten chiefdoms in the North and South.

A team from the World Bank led by Pamela Dale completed a study of Timap in 2009. Researchers randomly selected cases from three of Timap’s offices, and interviewed all the parties involved. An imam in Bo District said to the researchers, “Before Timap, people who didn’t have money to sue to the chiefs or court resorted to either fighting or swearing or sorcery as a way of investigating or satisfying their desire to seek justice.” The study found that clients were attracted to Timap because its service was “free, fast, and fair,” and “associated in many respondents’ minds with fair solutions.”Footnote 9

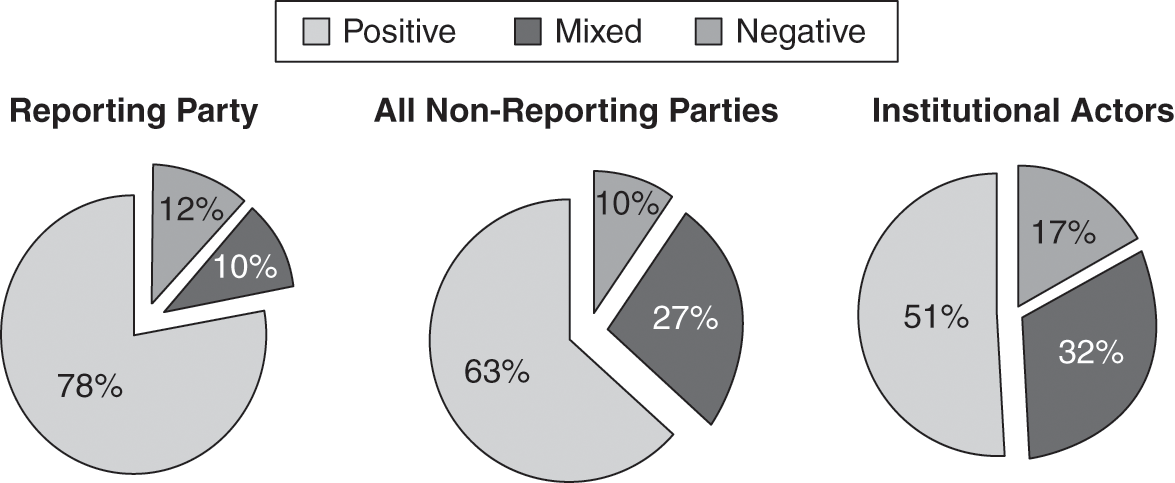

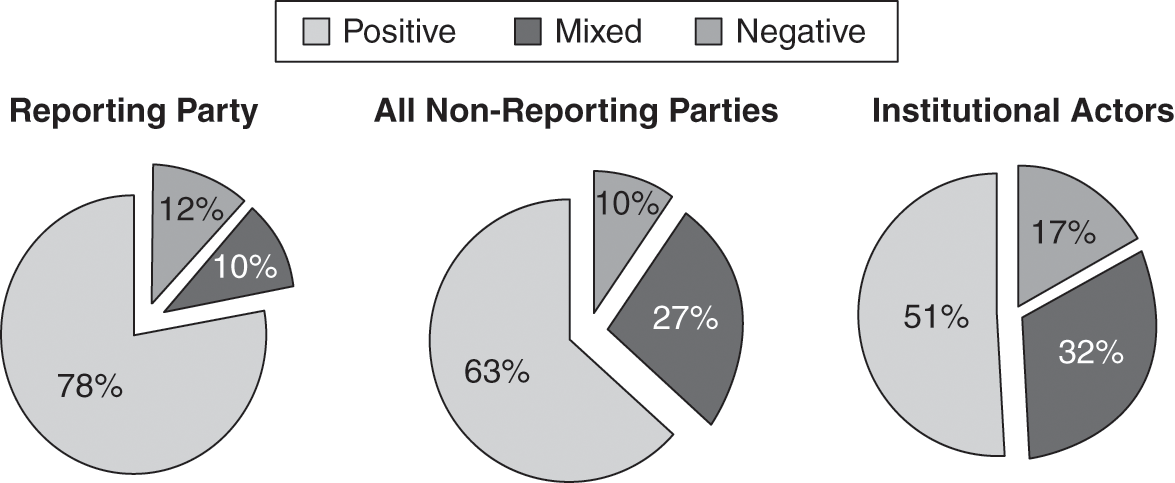

Figure 6.1 Satisfaction with Timap, reporting versus non-reporting parties.

Fifty-five percent of cases sampled in the World Bank study involved family law – issues like alimony and child custody – though paralegals addressed many other kinds of problems as well: violations of labor rights, disputes over land and debt, and assault. In addition to the random sample, researchers asked paralegals to identify a few “high impact” collective cases in each site – these included supporting workers at a sugar factory to seek compliance with a collective wage agreement, and supporting several villages to advocate with the Sierra Leone Roads Authority for repair of a broken bridge on the main road connecting them to the provincial capital.

Dale found that a large percentage of reporting (i.e., those who brought cases to paralegals) and non-reporting parties, and even a narrow majority of institutional actors – whom paralegals sought to hold accountable – spoke positively of their experience working with Timap.

Clients – especially women and young people – reported that “Timap’s presence and advocacy … encouraged them to demand rights that may otherwise have gone unrecognized.” Many informants perceived that “police, chiefs, and courts … were more thorough, fair, and fast in their dispute resolution” as a result of monitoring and advocacy by the paralegals.Footnote 10

Dale identified several areas for improvement. A few respondents indicated that paralegals had taken on cases involving family members and friends. Dale recommended better enforcement of Timap’s conflict of interest policy, which would require paralegals to recuse themselves from those cases. Dale also found that many clients could not describe Timap’s work in detail beyond their own cases; she recommended clear, consistent communication on the role Timap plays in the community. She also noted that some case files were missing or incomplete, and emphasized the importance of more rigorous management of case information.Footnote 11

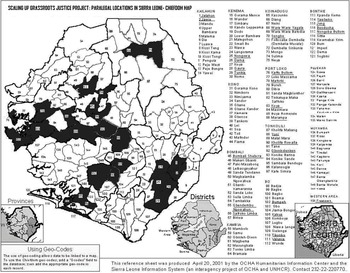

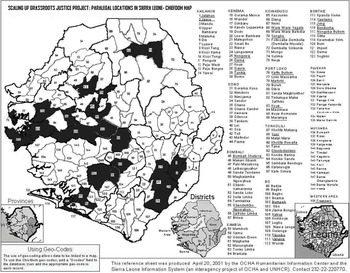

Figure 6.2 Scaling up grassroots justice: Chiefdoms served by paralegals as of 2011.

In 2010, President Koroma and the Open Society Foundation agreed to support a further scale-up of community paralegals. Timap, the Catholic Access to Justice Project, two other faith-based groups – the Methodist Church and the Catholic Justice and Peace Commission – and the Bangladeshi NGO BRAC all agreed to apply the Timap model with common systems for training, data collection, and paralegal supervision. A small team from the Open Society Justice Initiative coordinated the coalition and supported new partners to adapt Timap’s methodology.

Together, by the end of 2010, the organizations deployed more than seventy paralegals in eight out of Sierra Leone’s twelve districts, and served an estimated 38 percent of the population in the country.

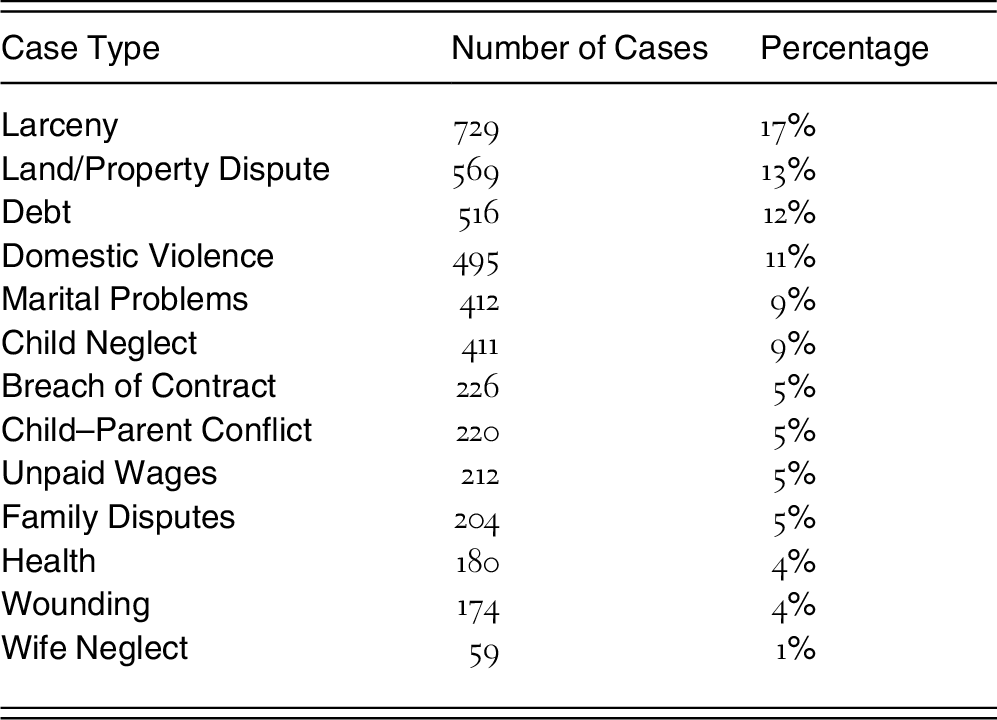

In 2013, paralegals from the five organizations collectively opened 6,031 new cases and resolved 4,306. The cases were diverse – they included abuse of power by local authorities, accident compensation, unpaid wages, and breaches in the delivery of basic services like water and health care. The following tables show the most prominent case types and the kinds of actions paralegals took to address them.

Figure 6.3 Common case types (2013)

| Case Type | Number of Cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Larceny | 729 | 17% |

| Land/Property Dispute | 569 | 13% |

| Debt | 516 | 12% |

| Domestic Violence | 495 | 11% |

| Marital Problems | 412 | 9% |

| Child Neglect | 411 | 9% |

| Breach of Contract | 226 | 5% |

| Child–Parent Conflict | 220 | 5% |

| Unpaid Wages | 212 | 5% |

| Family Disputes | 204 | 5% |

| Health | 180 | 4% |

| Wounding | 174 | 4% |

| Wife Neglect | 59 | 1% |

Note: Some cases involve more than one issue. This table is based on the most prominent issue per case.

Starting in 2010, this group of organizations began to advocate for formal recognition from government for the role paralegals play. In 2012, Sierra Leone passed the Legal Aid Law that establishes a national Legal Aid Board and, among other things, calls for a paralegal in every chiefdom. Government has been slow to implement this law, and many government functions were interrupted during the Ebola epidemic. But the Legal Aid Board was constituted, and a director appointed, in 2015. As of this writing in 2018, the Board has begun to support some paralegals assisting pretrial detainees, but it has not certified or funded paralegals serving communities on a wider range of justice issues.

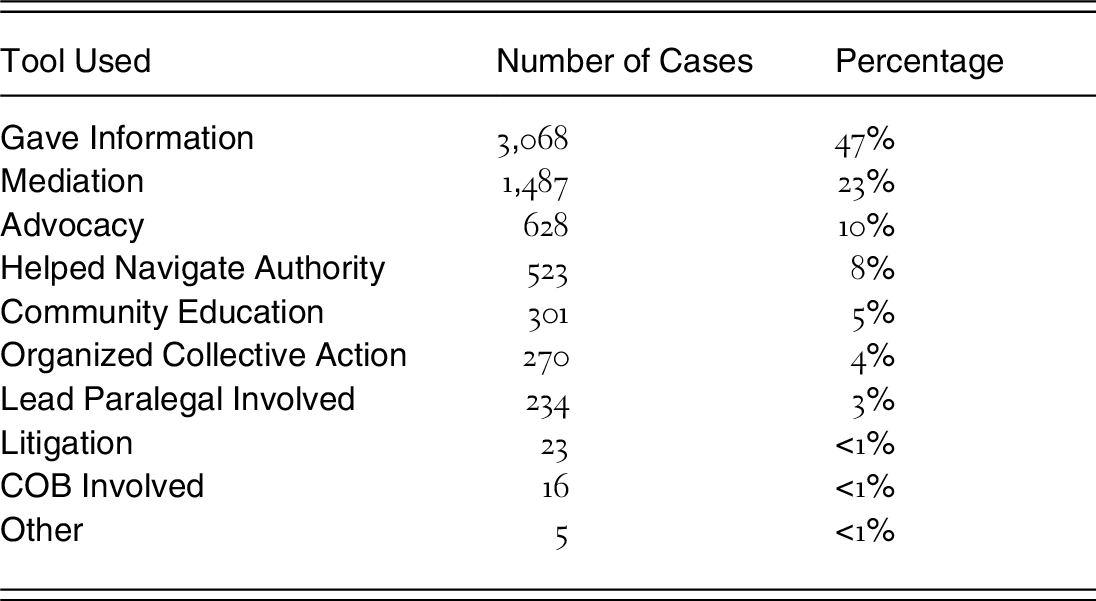

Figure 6.4 Primary action taken by paralegals to resolve cases (2013)

| Tool Used | Number of Cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gave Information | 3,068 | 47% |

| Mediation | 1,487 | 23% |

| Advocacy | 628 | 10% |

| Helped Navigate Authority | 523 | 8% |

| Community Education | 301 | 5% |

| Organized Collective Action | 270 | 4% |

| Lead Paralegal Involved | 234 | 3% |

| Litigation | 23 | <1% |

| COB Involved | 16 | <1% |

| Other | 5 | <1% |

Note: Paralegals take more than one type of action in many cases. This table is based on the one approach to which paralegals gave the greatest emphasis in any given case.

In the meantime, some paralegals have honed their focus on cases involving the greatest imbalances of power, like conflicts between rural communities and mining or agriculture companies.

To offer a closer look at how paralegals work, we turn now to present data from our case-tracking research.

III. Case Tracking of a Representative Sample of Paralegal and Non-paralegal Cases

A. Methods

We collaborated with a team of field researchers to study in detail the work of three organizations – Timap for Justice, the Network Movement for Justice and Development, and the Methodist Church of Sierra Leone – across five chiefdoms. We chose cases at random from the dockets of these organizations.Footnote 12

If clients from selected cases consented to take part in the study, researchers reviewed the case file. They then interviewed clients, paralegals, and all other major actors in the case, including officials and parties against whom complaints were brought. These interviews were semi-structured; based on each interview the researchers filled out standard data collection instruments.

To create a basis for comparison, we conducted similar case tracking in five chiefdoms where paralegals were not operating. There, we generated “dockets” by asking people involved in dispute resolution – chiefs, elders, religious leaders – about cases they had handled. We selected cases at random from that list, and then followed a similar process, interviewing all parties involved in each case, and filling out the same standard data collection instruments.

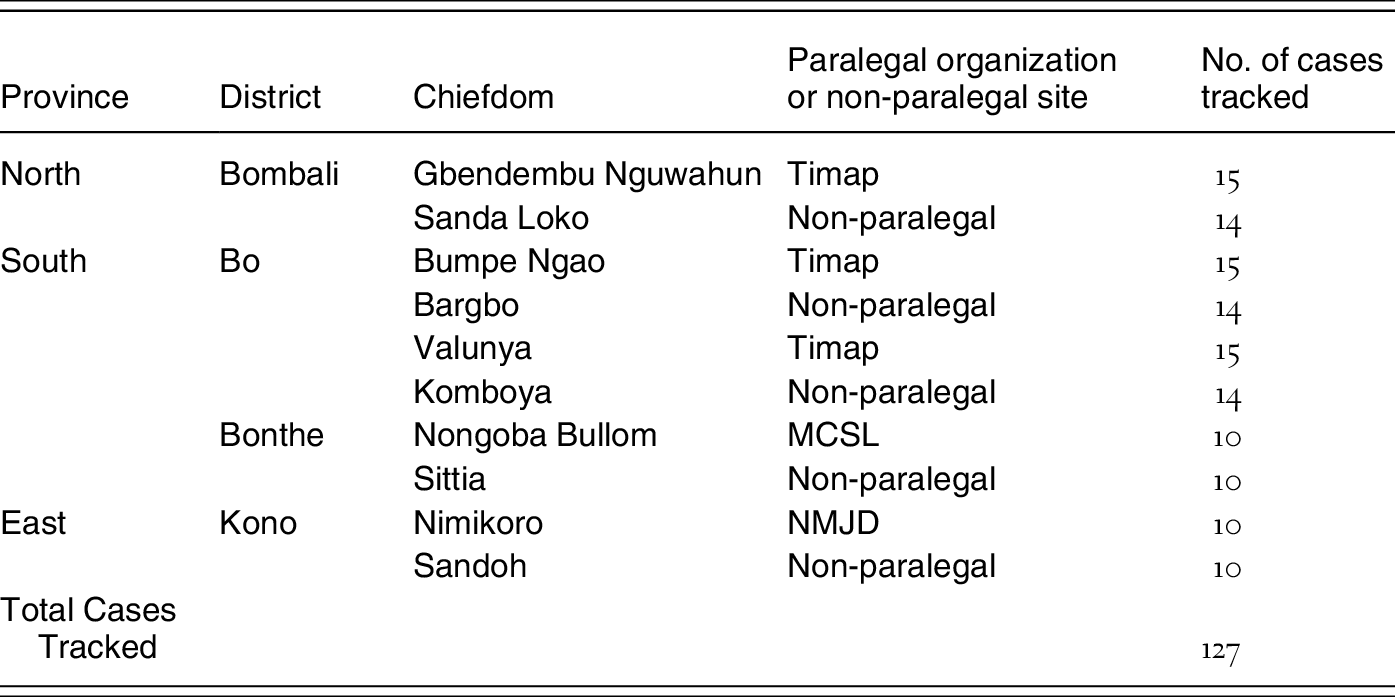

In all, a team of five researchers, under the close supervision of two of us, Lyttelton Braima and Gibrill Jalloh, conducted a total of 460 interviews to track 127 cases. The table that follows shows the distribution of cases tracked across location and paralegal organization.

Figure 6.5 Distribution of cases tracked

| Province | District | Chiefdom | Paralegal organization or non-paralegal site | No. of cases tracked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Bombali | Gbendembu Nguwahun | Timap | 15 |

| Sanda Loko | Non-paralegal | 14 | ||

| South | Bo | Bumpe Ngao | Timap | 15 |

| Bargbo | Non-paralegal | 14 | ||

| Valunya | Timap | 15 | ||

| Komboya | Non-paralegal | 14 | ||

| Bonthe | Nongoba Bullom | MCSL | 10 | |

| Sittia | Non-paralegal | 10 | ||

| East | Kono | Nimikoro | NMJD | 10 |

| Sandoh | Non-paralegal | 10 | ||

| Total Cases Tracked | 127 |

B. Results

The following tables summarize results across paralegal and non-paralegal sites on questions like who initiated cases, what issues were involved, and how fair the parties perceived the outcomes to be. Several of the differences between paralegal and non-paralegal organizations are statistically significant, but we omit formal tests because of possible bias in the selection of non-paralegal cases – we discuss this under “perceptions of fairness” later in this chapter. The number of respondents varies from table to table because not all interviewees answered all questions.

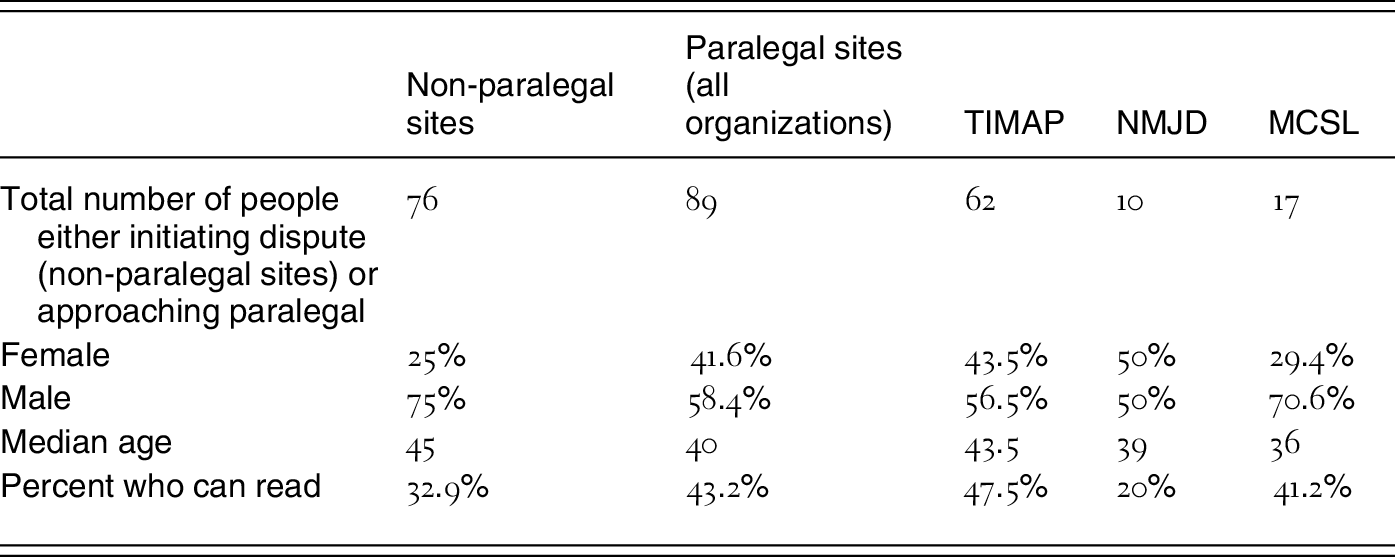

Figure 6.6 Who brought complaints?

| Non-paralegal sites | Paralegal sites (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of people either initiating dispute (non-paralegal sites) or approaching paralegal | 76 | 89 | 62 | 10 | 17 |

| Female | 25% | 41.6% | 43.5% | 50% | 29.4% |

| Male | 75% | 58.4% | 56.5% | 50% | 70.6% |

| Median age | 45 | 40 | 43.5 | 39 | 36 |

| Percent who can read | 32.9% | 43.2% | 47.5% | 20% | 41.2% |

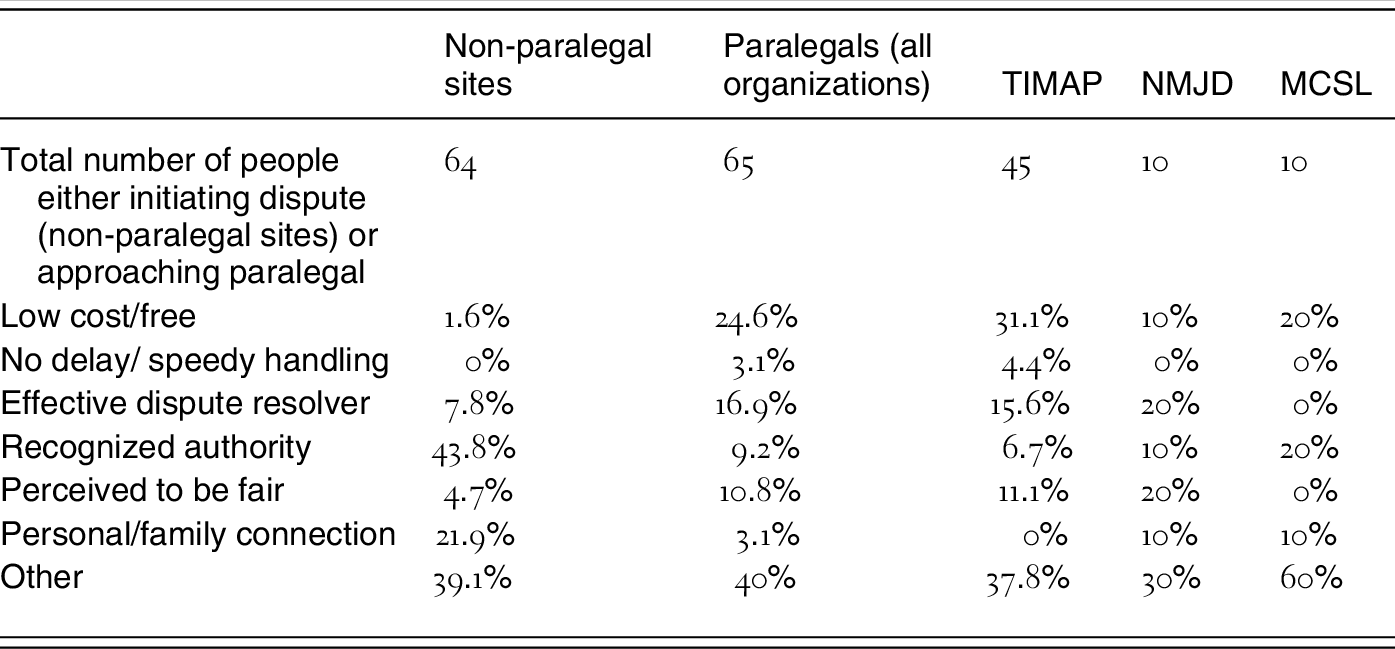

Figure 6.7 Why did they choose the institution or organization they approached?

| Non-paralegal sites | Paralegals (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of people either initiating dispute (non-paralegal sites) or approaching paralegal | 64 | 65 | 45 | 10 | 10 |

| Low cost/free | 1.6% | 24.6% | 31.1% | 10% | 20% |

| No delay/ speedy handling | 0% | 3.1% | 4.4% | 0% | 0% |

| Effective dispute resolver | 7.8% | 16.9% | 15.6% | 20% | 0% |

| Recognized authority | 43.8% | 9.2% | 6.7% | 10% | 20% |

| Perceived to be fair | 4.7% | 10.8% | 11.1% | 20% | 0% |

| Personal/family connection | 21.9% | 3.1% | 0% | 10% | 10% |

| Other | 39.1% | 40% | 37.8% | 30% | 60% |

Note: Respondents could identify more than one reason for choosing their forum, so percentages in most columns total more than 100 percent.

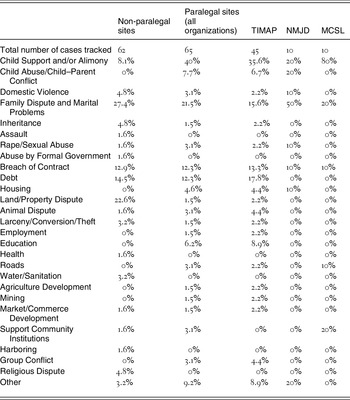

Figure 6.8 What kinds of cases?

| Non-paralegal sites | Paralegal sites (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of cases tracked | 62 | 65 | 45 | 10 | 10 |

| Child Support and/or Alimony | 8.1% | 40% | 35.6% | 20% | 80% |

| Child Abuse/Child–Parent Conflict | 0% | 7.7% | 6.7% | 20% | 0% |

| Domestic Violence | 4.8% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 10% | 0% |

| Family Dispute and Marital Problems | 27.4% | 21.5% | 15.6% | 50% | 20% |

| Inheritance | 4.8% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Assault | 1.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Rape/Sexual Abuse | 1.6% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 10% | 0% |

| Abuse by Formal Government | 1.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Breach of Contract | 12.9% | 12.3% | 13.3% | 10% | 10% |

| Debt | 14.5% | 12.3% | 17.8% | 0% | 0% |

| Housing | 0% | 4.6% | 4.4% | 10% | 0% |

| Land/Property Dispute | 22.6% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Animal Dispute | 1.6% | 3.1% | 4.4% | 0% | 0% |

| Larceny/Conversion/Theft | 3.2% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Employment | 0% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Education | 0% | 6.2% | 8.9% | 0% | 0% |

| Health | 1.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Roads | 0% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 0% | 10% |

| Water/Sanitation | 3.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Agriculture Development | 0% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Mining | 0% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Market/Commerce Development | 1.6% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Support Community Institutions | 1.6% | 3.1% | 0% | 0% | 20% |

| Harboring | 1.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Group Conflict | 0% | 3.1% | 4.4% | 0% | 0% |

| Religious Dispute | 4.8% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Other | 3.2% | 9.2% | 8.9% | 20% | 0% |

Note: Cases can involve more than one issue, so percentages in each column total more than 100 percent.

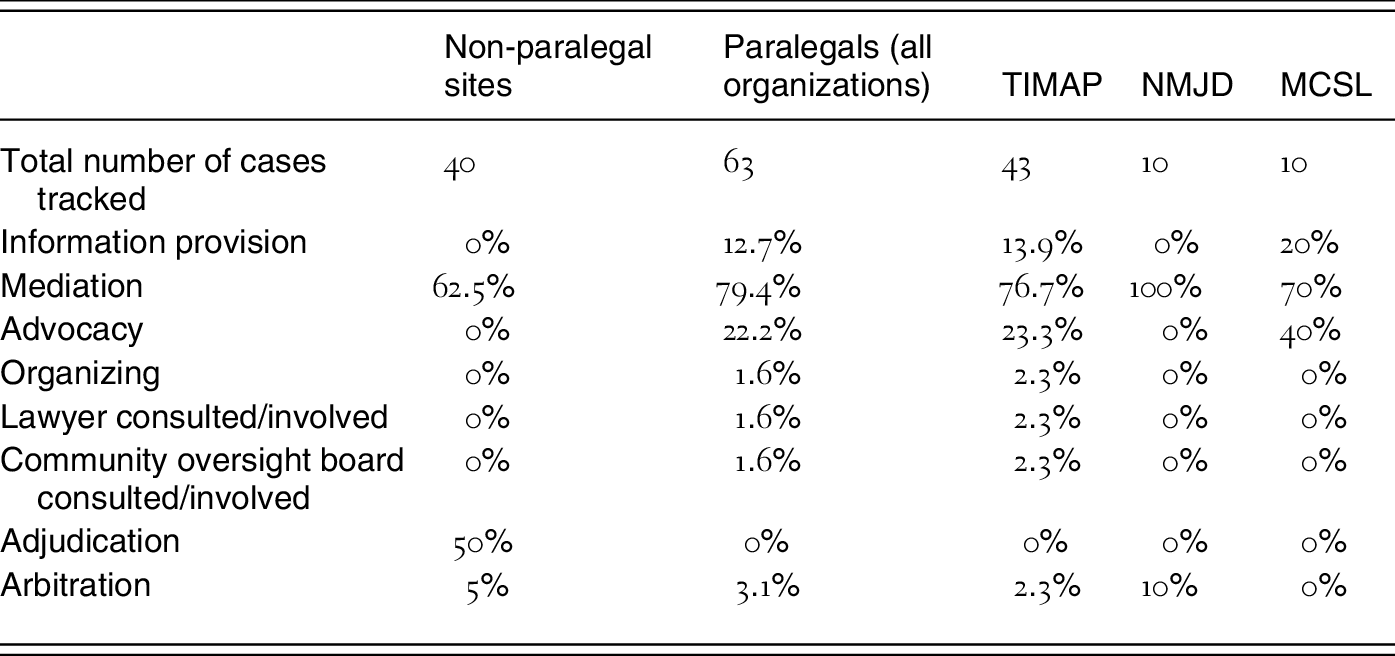

Figure 6.9 What methods were used in addressing the case?

| Non-paralegal sites | Paralegals (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of cases tracked | 40 | 63 | 43 | 10 | 10 |

| Information provision | 0% | 12.7% | 13.9% | 0% | 20% |

| Mediation | 62.5% | 79.4% | 76.7% | 100% | 70% |

| Advocacy | 0% | 22.2% | 23.3% | 0% | 40% |

| Organizing | 0% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 0% | 0% |

| Lawyer consulted/involved | 0% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 0% | 0% |

| Community oversight board consulted/involved | 0% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 0% | 0% |

| Adjudication | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Arbitration | 5% | 3.1% | 2.3% | 10% | 0% |

Note: Paralegals and dispute handlers in non-paralegal sites sometimes employ multiple strategies in a single case, so percentages in most columns total more than 100 percent.

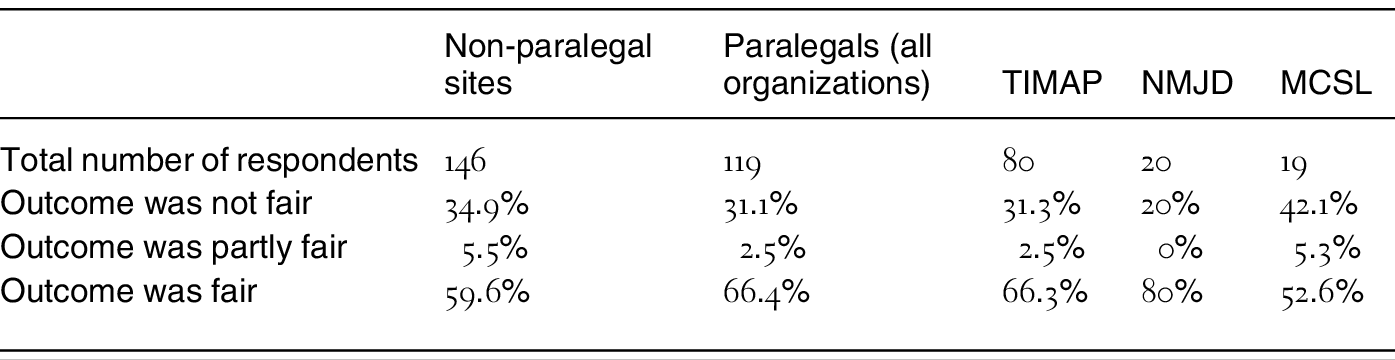

Figure 6.10 How did parties perceive the outcomes? (all interviewees)

| Non-paralegal sites | Paralegals (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of respondents | 146 | 119 | 80 | 20 | 19 |

| Outcome was not fair | 34.9% | 31.1% | 31.3% | 20% | 42.1% |

| Outcome was partly fair | 5.5% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 0% | 5.3% |

| Outcome was fair | 59.6% | 66.4% | 66.3% | 80% | 52.6% |

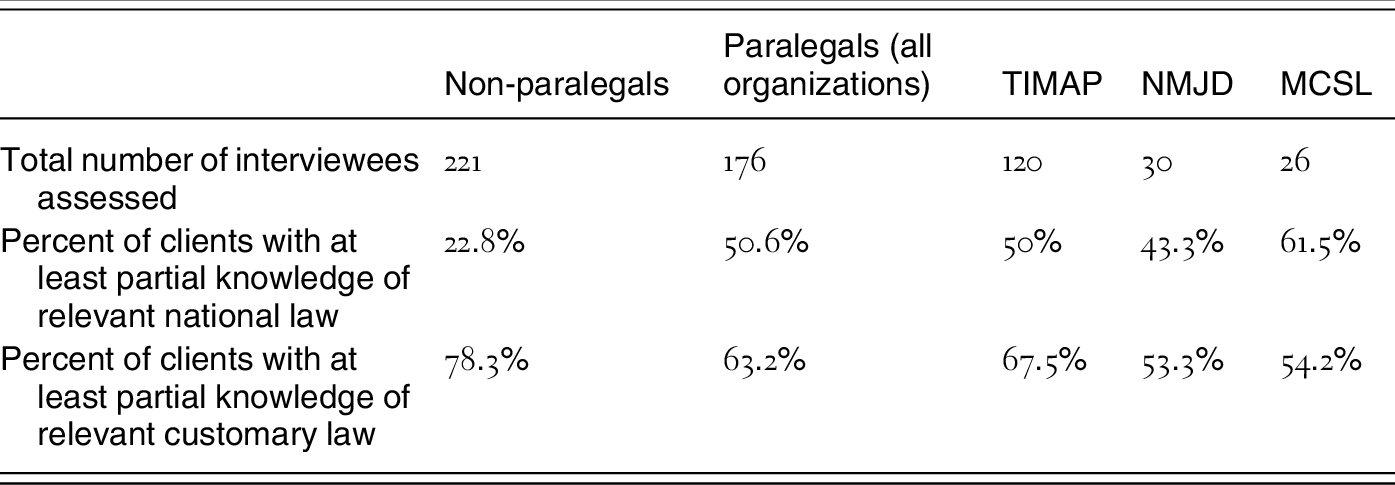

Figure 6.11 Were participants aware of relevant law?

| Non-paralegals | Paralegals (all organizations) | TIMAP | NMJD | MCSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of interviewees assessed | 221 | 176 | 120 | 30 | 26 |

| Percent of clients with at least partial knowledge of relevant national law | 22.8% | 50.6% | 50% | 43.3% | 61.5% |

| Percent of clients with at least partial knowledge of relevant customary law | 78.3% | 63.2% | 67.5% | 53.3% | 54.2% |

Note: These data are based on assessments by the interviewing researchers.

We completed the case tracking in 2011. In addition, we interviewed paralegals, lawyers, and government officials – that research continued into 2018. We now draw on both the case-tracking data and the stakeholder interviews to explore the institutional, cultural, and organizational factors that shape the work of paralegals in Sierra Leone.

IV. Discussion

A. Compared with Traditional Institutions, Paralegals Focus More on the Rights of Women and on State and Corporate Accountability

We found significant differences between, on the one hand, the types of cases people brought to paralegals and, on the other hand, the types of cases handled by dispute-resolving institutions in the sites where paralegals were not active. Together, child support, alimony, and rape/sexual abuse made up 43 percent of all cases handled by paralegals, for example, but less than 10 percent of the cases we encountered in non-paralegal sites.

All of these cases involved complaints by women against men. We infer that women are bringing these cases more often to paralegals and less often to local authorities because of the bias of existing institutions. Customary and formal institutions alike offer weak protection for the rights of mothers, wives, and survivors of sexual violence.Footnote 13

Legal empowerment organizations prioritize gender equity. Paralegals receive training on, for example, three 2007 laws that expanded the legal rights of women and girls – the Domestic Violence Act, the Devolution of Estates Act, and the Child Rights Act.Footnote 14 Women see the paralegals as a source of help with problems that they would otherwise find difficult to resolve.

Forty-two percent of all clients approaching paralegals were women; in contrast 25 percent of the people initiating disputes in non-paralegal sites were women. One client, a mother of two children from Gbap village in Nongoba Bullom chiefdom, described the work of paralegals this way (translated from Krio):

Since the human rights [paralegals] came here, any time our men forsake us or beat us, the human rights people talk for us women. Like this my own case, if the human rights people weren’t here to talk for me, I would have been taking care of myself and my child alone, my man wouldn’t have lifted his hand to help.Footnote 15

Two other categories made up a significant proportion of the cases of one of the paralegal organizations, Timap for Justice, but were comparatively rare in non-paralegal sites. Grievances with respect to public services and infrastructure – education, health care, housing, roads, water, and sanitation – made up 15.5 percent of Timap’s cases, but less than 5 percent of the cases in non-paralegal sites. Grievances with respect to livelihood development and/or the private sector – agriculture, mining, employment, market development – made up another 8.8 percent of Timap’s cases but only 1.6 percent of the cases in the non-paralegal sites.

Here too, we attribute the differences at least in part to the nature of existing institutions. The local authorities we approached in non-paralegal sites – chiefs, chiefdom administrators, religious leaders – tend to have little power or inclination to challenge corporations or the administrative state.Footnote 16 As a result their constituents often do not bother to bring those kinds of grievances to them. Moreover, failed public services are so much the norm that many Sierra Leoneans would not think to complain about them at all.Footnote 17

Timap paralegals, in contrast, proactively encourage communities to take action on exactly these kinds of issues. The paralegals conduct community meetings on topics like education and agriculture policy. The discussions often reveal that a specific state failure or a corporate abuse is not only a moral wrong – it’s a violation of law. Paralegals then suggest channels by which communities can pursue redress. Paralegals support clients to go beyond local authorities – to engage district councils, line ministry officials, and company managers.

The other two organizations in our study were relatively new and had provided less training to their paralegals at the time of the research. Our findings were consistent with what those organizations told us – that their paralegals were as yet focused primarily on intra-community disputes rather than problems involving the state or private firms.

B. In Intra-community Disputes, Paralegals Advocate for a Fair Solution if Mediation Does Not Result in One

When paralegals help people take on intra-community disputes, they play a different role from traditional dispute resolvers. Chiefs in Sierra Leone are technically barred from adjudication, but in practice they run their own courts.Footnote 18 Indeed half the cases we observed in non-paralegal sites involved adjudication. Other dispute resolvers – religious leaders, elders, youth leaders – engage in either mediation (63 percent of cases in non-paralegal sites) or arbitration (5 percent of cases in non-paralegal sites).Footnote 19

Paralegals mediate in intra-community disputes as well – they did so in 79 percent of the cases in our sample – but in a different way. Paralegals prioritize educating people about national law, and they attempt to mediate in its shadow. We found that paralegal clients were more than twice as likely to have at least partial knowledge of relevant national law than parties to disputes in non-paralegal sites.Footnote 20

If mediation does not result in an agreement that paralegals and clients consider reasonably just, paralegals help clients to advocate with authorities for a remedy. Paralegals engaged in advocacy in 22 percent of their cases; dispute resolvers in non-paralegal sites did not engage in advocacy at all.

These differences between paralegals and existing dispute resolvers are reflected in the reasons people cited for choosing to approach them. Compared with people in non-paralegal sites, paralegal clients were more than twice as likely to cite “perceived to be fair.” Clients also chose paralegals to avoid what are often described as abusive fees charged by chiefs – 25 percent of paralegal clients cited “low cost/free,” as compared with 2 percent of parties in non-paralegal sites.

In contrast, people in non-paralegal sites were more likely to choose their resolution forum because it was a “recognized authority” or a “personal or family connection” (44 percent and 22 percent, respectively, as compared with 9 percent and 3 percent among paralegal clients). People approach paralegals, in sum, because paralegals do not charge fees and because they will advocate for a solution that is fair to the weaker party.

C. Mr. Bona, from Bumpeh Ngao Chiefdom, and His Land Dispute

The case of Mr. Bona,Footnote 21 from Bumpe Ngao chiefdom, illustrates how paralegals engage in mediation to assist parties whose rights are being abused. Mr. Bona supported a family of eighteen by cultivating a parcel of land near Fulaninahun village. He said the land has been in his family for generations, and that he had tilled it himself for more than a decade without dispute. But in 2010 Mr. Kapuwa, from a neighboring village, claimed the land belonged to his family instead. This sparked a bitter dispute.

Local chiefs barred both families from the land until the matter was resolved. Mr. Bona pleaded with the chiefs not to impose the ban until he harvested cassava he had already planted for that season. The chiefs refused; instead, they promised swift resolution of the matter.

Mr. Bona obeyed the ban. But the chiefs’ inquiry dragged on, and Mr. Bona struggled to feed his family while the crops he’d planted began to rot on the ground. Mr. Bona’s nephew (a junior high school pupil and one of his dependents) took part in a legal awareness session organized by paralegals in another village. The nephew suspected collusion between the chiefs and Mr. Kapuwa to confiscate his uncle’s land. He advised his uncle to approach the paralegals.

On receiving the complaint, paralegal Joseph Sawyer went to the two villages and first met with the chiefs, then with Mr. Kapuwa. After gathering facts and viewpoints from both sides, Sawyer initiated a mediation including the disputing parties and traditional leaders.

The first stage of mediation resulted in the relaxing of the ban on the farm, allowing Mr. Bona to harvest his cassava while the mediation continued. Ultimately seven witnesses addressed the group, and all but one confirmed that Mr. Bona’s family had farmed the land since the founding of the village. Mr. Kapuwa agreed to abandon his claim on the condition that Mr. Bona perform a swearing ritual in which he would affirm his true ownership of the land. Mr. Bona accepted, and swore in the presence of the paralegal Joseph Sawyer and the chiefs.

Mr. Bona told researchers that Sawyer “restored the lifeline of my family,” something he attributed to Sawyer’s skill in mediation. Bona’s nephew said Sawyer “demonstrated inclusiveness and fairness in handling the matter.”

Sawyer did not invoke a specific national law in this case, but he said his association with law in general – and a lawyer who could litigate in select cases – served as a check on abusive behavior by chiefs. The solution itself – the swearing ritual – was based on custom. An advantage of the paralegal approach in Sierra Leone is its ability to straddle the customary and formal systems.

D. Increasing Focus on Land and Environmental Justice

Our case-tracking research was completed in 2011. Since then, some paralegals have shifted focus away from intra-community disputes and toward cases involving state institutions and private firms, on the view that the imbalances of power are greater and the added value of paralegals is higher. In those kinds of cases – like the one involving Cluff Gold Company, with which we opened the chapter – paralegals do not engage in mediation at all; instead they help communities to advocate with authorities and negotiate with firms.

In particular, there is an acute need to protect community rights to land and environment. In the past decade government has aggressively courted large-scale agriculture and mining investments. The government has doubled down on this strategy as a way of restarting the economy after the Ebola epidemic.Footnote 22 Most land is held by communities and families under customary tenure, without recognized maps or clear processes for decision-making. The combination of weak land rights and increased investment interest has led to inequitable, environmentally irresponsible deals and sometimes outright theft.Footnote 23

Institutional context shapes the way paralegals support communities in relation to these threats. Namati, an international legal empowerment group, works with paralegals focused on land and environmental justice in both India and Sierra Leone.Footnote 24 In India, the paralegals help communities pursue remedies from administrative institutions, including pollution control boards, coastal zone management authorities, and district governments.

Many communities there have lived near industry for decades. They have often attempted on their own to request relief from firms, with little success. The contribution of paralegals is to help people invoke law and the regulatory authority of the state instead.Footnote 25

In Sierra Leone, in contrast, large-scale development projects are relatively new, environmental law is nascent, land law is outdated,Footnote 26 and regulatory institutions are very weak. Paralegals and communities in Sierra Leone have tried repeatedly but never succeeded in persuading the Environmental Protection Agency to take enforcement action, for example. They have had greater – though still modest – success negotiating directly with firms.Footnote 27

Even when those negotiations result in a partial remedy, they do not strengthen the regulatory function of the state. Namati Sierra Leone advocates for better rules and stronger institutions based on its case experience, but the state’s fundamental lack of capacity is a major limitation.

Paralegal efforts in relation to land and environment are also shaped by the place of chiefs in Sierra Leonean society. Under customary law no one owns land per se – it belongs to the ancestors and the descendants who are not yet born. Chiefs are stewards, not owners. Families have strong use rights, and in principle decisions about land can only happen with their consent.Footnote 28 But in practice many chiefs make decisions on their own.Footnote 29 As a result collective cases are often vulnerable to elite capture.

E. Securing Partial Redress from the Sierra Leone Diamond Corporation

A case from Bumpeh chiefdom illustrates both of these trends: the tendency to negotiate directly with firms for remedies rather than engage the state, and the risk of chiefs undermining collective action. The case involved what was then called Sierra Leone Diamond Corporation (SLDC), now called African Minerals Limited.

SLDC made grand promises – cash payments to landowning families, jobs for youths, a school, roads – in exchange for the chance to mine on what was previously farmland across six villages. The company mined for several years while fulfilling almost none of those promises. Then it closed its operations without notice. The company left behind several unfilled pits that were each one to two stories deep and about the length of an Olympic swimming pool.

SLDC had dammed the river Kpejeh, which caused flooding on people’s farms, and its trucks had broken the single bridge that connected the six villages to the main road. Several community members visited the office of SLDC in Bo Town, the capital of the southern province, to complain. They were ejected from the premises by security guards.

The communities then approached paralegal Marian Tebbi, who was based in Kaniya, one of the six affected villages. Marian worked with farmers to document the damage and record what if any compensation had been paid. For a large case like this, she invoked her vertical network – lead paralegal Daniel Sesay and directors Vivek Maru and Simeon Koroma.

Together they researched mining law. Substantively, the firm’s actions constituted clear legal violations.Footnote 30 But procedurally, at the time in 2006, there was no administrative process or institution through which communities could seek redress for grievances against mining companies.

The courts might have been an option, but Timap and other legal empowerment groups treat litigation as a last resort. Courts are expensive, slow, and sometimes subservient to the executive branch. Moreover, the process of litigation is so technical and removed that it’s difficult to fulfill the legal empowerment ideal of placing clients in the driver’s seat. Litigation can easily become “I’ll solve this for you” rather than “we’ll solve it together.”

Instead Timap and the communities decided to petition SLDC directly. They wrote a letter outlining the harms and specifying the violations of law. Even without court or administrative action, the invocation of law can have some sway.Footnote 31 The firm was initially responsive and expressed a willingness to remedy the damages.

But after about a month company officials stopped answering calls or taking meetings. Timap tried extending the vertical network one more notch, by contacting Clare Manuel, a lawyer in the United Kingdom who engaged in pro bono work related to corporate accountability. Ms. Manuel wrote to SLDC’s office in London, asking for remedial action in Bumpeh and threatening a complaint to the ombudsman of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Almost immediately, the Timap team started receiving calls from SLDC officials in Freetown. “Our bosses in London want this resolved. How can we solve this problem?” After a meeting with Timap staff, including paralegal Marian, and representatives from the six villages, the company took several concrete steps. It removed the debris blocking the river Kpejeh, it repaired the bridge, and it paid community members to fill the pits.

The negotiations stalled, however, on the point of compensation. Timap and the communities requested monetary damages for the loss of crops and fruit and palm trees. Marian created a detailed docket on the specific claims of each farmer.

On a day when Marian had left her village to attend a training in Freetown, SLDC’s public relations officer visited Kaniya. He offered free mobile phones and the equivalent of about US$2,000 in cash to chiefs of the six villages. He asked the chiefs to put their thumbprints on an agreement that settled all claims. Timap had requested that the communities not interact with SLDC without contacting Marian, and had made the same request to SLDC in writing.

This was during what Sierra Leoneans call “hungry season” – the months before the annual harvest, when crops from the previous year are running low. The chiefs took the money and phones, and offered their thumbs. Timap found out when Marian returned. Many of the affected farmers were furious. The chiefs had distributed much of the cash among village residents, but the sums were paltry compared with what the farmers felt they were owed.

At a long community meeting several weeks later, the chiefs apologized to their own citizens and to Timap. The chief of Kaniya said, “the hunger and the cash made us blind.” Timap leadership said it would be difficult to pursue the case further, and indeed SLDC never returned and never paid another Leone.

F. Advocating for Effective Regulation: Collaborating when Possible and Crossing the Line between Law and Politics

International lawyers like Ms. Manuel can be helpful in cases involving multinational firms. But they are no substitute for a functioning regulatory regime. In 2013, the Environment Protection (Mines and Minerals) Regulation laid out clearer procedures for addressing community grievances,Footnote 32 but those procedures have not been implemented as of this writing.

To pursue remedies from the state, communities need to have access to the regulatory conditions under which firms operate. In India, when community members approach a paralegal with a complaint about a company – air emissions are causing sickness, say, or water pollution is killing fish – the paralegals’ first move is to obtain the firm’s regulatory clearances and permits.

Those typically include an environmental clearance from the ministry of environment, a consent to operate from the pollution control board, and sometimes, depending on the location, a forest clearance or a coastal clearance. Paralegals translate those documents into the local language and explain in simple terms the conditions contained in them.

A factory might be required to use a specific air filtration system, for example, or run its effluents through a treatment plant, or mitigate dust pollution with a boundary wall of a specific height. Paralegals and communities can then compare what’s in the conditions with reality, and use the discrepancies to file an administrative complaint.Footnote 33

In Sierra Leone, similar regulatory permits exist in principle. Most industrial and agricultural projects need an environmental license, for example, which should contain binding conditions growing out of the environmental impact assessment process.Footnote 34

But Namati Sierra Leone, which focuses exclusively on land and environmental issues, has not been able to access a single environmental license. Paralegals have filed requests using Sierra Leone’s Right to Information law; those requests have been ignored. As of this writing, Namati is considering litigation under the Right to Information Act to obtain licenses and other project documents. Legal empowerment is difficult if people are not allowed to see what the law requires.

The opacity may stem from an even deeper problem: corruption.Footnote 35 In one case involving a Chinese iron ore mine in the north of the country, where poisonous tailings were flowing openly onto farmland, and drinking water was severely contaminated, an officer of the Environmental Protection Agency said to Namati paralegals: “We’re glad you’re working on this. We’re not going to be able to do much about it though, because the President is personally interested in the project.”Footnote 36

Legal empowerment groups try to help build the state their clients need. Namati offered extensive suggestions for Sierra Leone’s 2015 Land Policy, for example, based on challenges and patterns that emerged from case experience. The parliamentary committee overseeing the policy insisted that Namati’s inputs be incorporated. Namati is now partnering with the Ministry of Lands to pilot provisions in the policy that would allow communities to receive formal tenure over their customary lands.

In a similar spirit, the director of Timap for Justice, Simeon Koroma, represents civil society on the governing body of the Legal Aid Board. Koroma aims to help the board fulfill the progressive potential of the 2012 Legal Aid Law.

But legal empowerment groups sometimes conclude that collaborative engagement is not enough. Faced with many environmental justice cases in which firms are intransigent and government is unresponsive, Namati Sierra Leone joined with others to launch a public pledge, “Our Land Our Future,” in advance of Sierra Leone’s 2018 national election. The pledge asks candidates to commit to a set of reforms. These are measures that communities and paralegals identified as most important based on their attempts to seek justice.

There are eleven measures in all; here are two: “Establish accessible grievance redress mechanisms that provide real remedies for social and environmental violations by corporations” and “Ensure the public, and in particular the communities directly affected, have full access to key information related to mining or agriculture projects. This includes environmental licenses, land lease agreements, community development action plans, and any private financial interest in companies held by politicians or public officials.”Footnote 37

As of this writing, ten local organizations, a private university, and several thousand citizens, many of whom come from communities where Namati paralegals work, have endorsed the pledge. The pledge represents an acknowledgment that an effective state can’t be built without politics.

This move from a legal frame to an openly political one poses risks. If one major party adopts the pledge and another doesn’t, paralegals could be seen as partisan. Depending on who wins the election, paralegals might experience less cooperation and greater retaliation from government.

The popular nature of the pledge – it is a consensus position by many organizations and citizens – may mitigate that danger. And work on land and environmental justice is risky no matter what.Footnote 38 Namati team members felt they would not be faithful to their mission if they did not evolve their work in this way. The goal of legal empowerment is to equip people to understand, use, and, when necessary, shape the law. The third of these, the shaping dimension, is ultimately and unavoidably political.

G. Organizing to Prevent Elite Capture

Alongside organizing for national change, paralegals organize locally to prevent elite capture.Footnote 39 When communities request support, Namati paralegals help them to select committees who will lead the effort to seek a solution. Paralegals ask that the committees include not just chiefs but women, young people, and what are called “strangers,” non-indigenes living in the affected community.

Paralegals also ask that any communication or information from the other party – usually mining or agricultural companies – be shared with all committee members and the paralegals, and that no decision be taken without consulting the affected population as a whole. Hassan Sesay, a former Timap paralegal who now works with Namati, says he spends a good deal of his time supporting these committees to function in an equitable and accountable way.

H. Financing and Recognition

In Sierra Leone, as in all the countries featured in this volume, paralegal groups grapple with the question of how to source sustainable and resilient revenue. The costs are relatively low. According to one estimate, paralegals could serve the entire country for US$2 million per year, or $0.34 per capita,Footnote 40 which is, by way of comparison, 3 percent of what the government allocated to health care in 2013.Footnote 41 But it is not clear where the money should come from over the long term.

The faith-based groups do draw on the considerable infrastructure of their sponsors, the Catholic and Methodist Churches. BRAC is the largest development NGO in the world, with more than US$600 million in annual revenue. In Bangladesh BRAC gives some support to its paralegal program from its wider operations, and to some extent the same is true in Sierra Leone.

But despite this institutional backing, those paralegal efforts and all the others in the country are presently funded largely by external donors – bilateral institutions like the British Department for International Development or Ireland’s Troicare, philanthropic groups like the Open Society Foundation, and multilaterals like the UN Development Program.

Reliance on foreign donors can be hazardous. The resources are time-bound and subject to factors unrelated to the work. For example, legal empowerment organizations successfully advocated that a British-sponsored justice sector reform project dedicate a portion of funds – about £2 million out of £25 million GBP over 2012–17 – to support community paralegals. The groups saw this as a chance to sustain paralegal efforts that grew with the help of the commitment from Open Society Foundations from 2009 to 2013.

But in the end a large portion of the funds allocated for paralegals under the UK project was spent on foreign consultants, and the remainder was pegged to specific project districts. As a result some existing paralegal efforts in districts not chosen by the project were forced to scale down, while in some districts that were chosen, the project struggled to find effective grantees.

Reliance on foreign donors also makes legal empowerment groups vulnerable to the charge of foreign interference. When governments seek to weaken domestic civil society, they often exploit the fact of foreign funding – by revoking permission to receive funds from abroad, for example, or by restricting the activities of foreign-funded NGOs.Footnote 42 The Sierra Leone government has not pursued a systematic policy of this kind as of this writing, but this is a risk to consider, especially as paralegals challenge larger-scale corruption.

One way to diversify from dependence on international donors is to pursue public funding. Legal empowerment groups advocated strenuously, over several years, for the 2012 Legal Aid Law and in particular the provisions recognizing the role of paralegals as legal aid providers. They saw statutory recognition as a source of legitimacy and a pathway to government revenue. In advocating for the law the organizations had to overcome opposition from Sierra Leone’s small private bar.

Sonkita Conteh began “10 Misconceptions about Paralegals in Sierra Leone,” an op-ed that ran in several Sierra Leonean papers in 2010, with this:

A few among the many lawyers I have had the opportunity to discuss the subject of “paralegals” with initially seemed to have deep suspicion of paralegals and their activities. Minutes into our conversation they realise that there is really no firm evidential basis to warrant a conviction so they drop all charges. Since I may not be able to talk to every individual lawyer or person who might have an unflattering opinion about the work of paralegals, I thought it prudent to … correct some of the most common misconceptions of paralegals.

The top four misconceptions in his list are “paralegals will impersonate lawyers,” “paralegals will charge fees,” “paralegals will want to appear in court,” and “paralegals are not properly trained.”Footnote 43 Conteh argues that there is little to no overlap between the clients paralegals serve and the ones who can pay for services from private lawyers. And just as microfinance initiatives have ultimately brought more people into the formal banking system, paralegals may ultimately increase business for lawyers, as a small percentage of their clients will require litigation.

A joint statement endorsed by twelve civil society groups argued:

Community-based paralegals can provide approachable, culturally acceptable, quick, inexpensive and effective ways to access justice. A legal aid framework that combines the proven utility of community based paralegal interventions with the representational role of legal practitioners has a more significant chance of making a dent in the huge access to justice deficit that the government seeks to reverse.Footnote 44

The 2012 law was a significant normative victory for the legal empowerment movement, and it has been cited in legislative debates elsewhere.Footnote 45 But with the exception of a small pilot focused on pretrial detainees, the law has not yet led to public financial support for paralegals.

In the meantime, some groups have explored the possibility of sector-specific solutions to the problem of sustainable revenue. Namati and others successfully argued, for example, that Sierra Leone’s 2015 Land Policy should require firms interested in land to contribute to an independent basket fund that will in turn support legal empowerment via paralegals for landowning communities.Footnote 46 The provision has not been implemented as of this writing, but in principle it could provide funding for paralegal efforts to address one set of problems for which they are needed.Footnote 47

If substantial funding does eventually flow from either the Legal Aid Board or the proposed land-focused legal aid fund, legal empowerment organizations will need to manage the risk of state interference in their work. The Legal Aid Board and the land-focused fund are both meant to be independent from the executive. But the Sierra Leonean government has arguably grown more authoritarian in recent years, and authoritarian regimes often find ways to steer ostensibly independent institutions.Footnote 48

Just as governments can restrict the activities of groups receiving foreign funds, similarly they can limit the activities or organizations to which domestic public funding is dedicated. Governments in general are often disinclined to pay for work that holds them accountable.Footnote 49

Even if public funding does go to some case-specific work that challenges abuses or failures by the state, it’s unlikely that government funds would support the systemic change campaign on land justice described in an earlier section. Those more explicitly political efforts would need to be financed independently.Footnote 50 So sole reliance on public revenue would also put the mission of legal empowerment at risk.

Another way to diversify revenue is to look to clients themselves. People are drawn to paralegals in part because they do not demand payment, and indeed the Legal Aid Act prohibits paralegals from charging for their services.Footnote 51 But it is possible for clients and communities to make voluntary contributions, in kind or otherwise. All the chiefdoms where Timap works have offered land on which Timap can build permanent offices, for example. And communities who have achieved remedies in large-scale land cases have sometimes contributed chickens, bags of rice, and money out of gratitude.

To date programs have not requested these donations, and the amounts do not defray a significant proportion of program cost.Footnote 52 It may be worth exploring whether programs can encourage community contributions without deterring those who cannot pay or damaging the reputation of paralegals for integrity. In principle community support can decrease the dependence of paralegals on outsiders and deepen the connection between paralegals and the people they serve.

Every source of funding has risks. For legal empowerment groups to be active in Sierra Leone for decades to come, they will need to find diverse enough revenue to weather the vicissitudes.

I. Perceptions of Fairness, Vertical Networks, and the Role of Case Data

At the outset of our research, we hypothesized that clients who worked with paralegals might express greater satisfaction with the way their cases were resolved as compared with cases in non-paralegal sites. That turned out to be true, but only by a narrow margin. Sixty-six point four percent of all interviewees in paralegal sites thought the outcome of their case was fair, as compared with 59.6 percent of interviewees in non-paralegal sites.

Three factors may have contributed to such a modest result. First, as we described earlier, paralegals were taking on different kinds of disputes from the ones we found in non-paralegal sites. Paralegals were more likely to be working on cases involving women’s rights and corporate or state accountability. In those areas, the institutional and cultural norms are particularly inequitable. So comparing the uphill battles in paralegal dockets with the more routine cases in non-paralegal sites may be like asking why a dozen pieces of cassava aren’t sweeter than a dozen mangoes.

Second, there was a difference in sampling methods between paralegal and non-paralegal sites. Where there were paralegals, we were able to take a random sample from case records. In non-paralegal sites, we relied on dispute resolvers to provide us with a list of cases from which we then selected a sample. Our field researchers felt chiefs and other dispute resolvers may have tended to share more successful and harmonious cases, and omit ones that involved abuse or exploitation. If true, this sampling bias in the non-paralegal sites would dilute any “fairness advantage” in paralegal cases.Footnote 53

Third, we observed variation in effectiveness, among individual paralegals and also among organizations. For three of the ten paralegals whose work we studied, 100 percent of the parties interviewed from their cases said the outcome of the case was fair; for three other paralegals, the average was below 60 percent. Of interviewees in cases handled by NMJD, 80 percent thought the outcome was fair; the proportion was 66.3 percent for Timap and 52.6 percent for the Methodist Church. So the variation across individual paralegals and across organizations was greater than the difference between paralegal and non-paralegal sites.

What causes this variation in paralegal effectiveness? Our qualitative findings suggest that the biggest factor is ongoing support and supervision. Where paralegals were part of a vertical network – they had a “lead paralegal” visiting them regularly and watching their performance, they had a lawyer whose help they could seek out in difficult cases – we saw paralegals handling cases well.

The SLDC and Cluff Gold cases described earlier are examples of the vertical network responding to tough problems. Paralegals Marian and Prince were able to make progress because of the help they had from lead paralegals and lawyers. Where paralegals were trained initially but then left largely on their own, as was the case with the one paralegal whose work we studied from the Methodist Church, we saw serious lapses, including disorganization and poor follow-up.Footnote 54

A rigorous system for tracking case information makes supervision and support possible. If there is a clear record of what has happened in every case, a supervisor can easily review strategy and progress during a visit. Better still, if those data are analyzed in aggregate, the organization can observe trends across paralegals and identify both common problems and useful innovations.

Rigorous data collection is crucial for a second reason. Data from across cases create a picture of how laws and systems are working in practice, something often no one else has. Organizations and the communities they serve can use that information to identify and advocate for positive systemic reforms. Tracking, aggregating, and analyzing data is time-consuming and difficult, especially because of Sierra Leone’s poor internet connectivity. But the returns in program quality and evidence-based advocacy seem worth the investment.

V. Conclusion: Can Paralegals Deepen Democracy?

Sierra Leone found peace after war. It regularly holds relatively free and fair elections. And it managed to extinguish Ebola. But from the perspective of many Sierra Leoneans, government steals from its people rather than serving them. The singer Emerson chants this, in his 2016 hit “Munku boss pa matches.”

Emerson doesn’t specify the identity of Adebayor, but it’s clear that he’s pointing at the state.Footnote 55

By equipping ordinary people to understand, use, and shape the law, community paralegals are attempting to deepen Sierra Leonean democracy. They are fighting to replace kleptocracy, authoritarianism, and impunity with a society in which rules and institutions work for everyone, including the least powerful.

It’s a bold vision. The cases paralegals and their clients manage to win make it tangible. But the opposing forces are strong. At best, it’s a long journey ahead.