Patrimonialism has been the prevailing form of political order that must be overcome in constructing rule-bound, effective, and legitimate government. Post-conflict countries are no exception to this pattern. In Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, international interventions that sought to establish one particular conception of political order found themselves in competition with the neopatrimonial practices preferred by domestic elites. The dynamic contest between these two visions of political order is especially apparent in the aftermath of a peacebuilding presence, when domestic elites and their supporters reassert patrimonial forms of politics that undermine the formal institutions of governance transplanted by interventions. As a result, a decade and more after the transformative peacebuilding missions in the three countries considered here, what is apparent is that patrimonial and rational–legal authority coexist in a quintessential neopatrimonial hybrid form – with personalized politics practiced within the institutional trappings of Weberian bureaucratic effectiveness and electoral democratic legitimacy.

Neopatrimonial political order operates through a system of rent-seeking and rent distribution through patronage.Footnote 1 Patron–client relationships form and persist on the basis of these distributional strategies, which bind elites to each other as well as to their social sources of support. In the liberal ideal associated with modern political order, by contrast, elites endowed with legitimate authority through the vote should use the rationalized bureaucracy to deliver programmatic public policies and collectively oriented goods and services. It is apparent from the experiences in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan that post-conflict elites, like their counterparts across the contemporary developing world, find that it is both easier and more profitable for them to focus, for the most part, on distributing narrowly targeted public rents and patronage goods to their clients in exchange for political support. One major insight of historical institutionalist theory is that actors use a variety of strategies to achieve change in political outcomes “beneath the veneer of apparent institutional stability.”Footnote 2 One such process is that of “conversion,” whereby actors can reshape institutions and policies to achieve objectives very different from the purposes for which they were originally created.Footnote 3 Thus, the characteristically hybrid nature of neopatrimonialism suits their ends very well: they perform their major functions in the formal institutional realms of state administration and electoral politics while maneuvering in more hidden and less risky ways to represent their own interests and those of their major client groups.

Analytical approaches that rely on more short-term measures of peacebuilding success and evaluate interventions as exogenous treatments are unfortunately restricted in seeing these gradual and endogenous processes of institutional change that continue to unfold. This chapter addresses this blind spot by tying international interventions to their aftermath, viewing the creation of post-conflict institutions as the beginning of the next phase of political contestation. It thus devotes further attention to the consequences of the institutional decisions made during the transitional governance process and the unfolding domestic political dynamics, as I assess the degree of state capacity and democratic consolidation in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan. Hewing to the historical institutionalist perspective, I examine how governance power shifts and settles through the institutional system, paying particular attention to the manner in which domestic elites use the institutional infrastructure to their advantage in consolidating their own grip on power. Two core elements of the nature of neopatrimonial political order in the three cases are highlighted. First, I emphasize that the effects of the transitional governance strategy last into the final phase of the peacebuilding pathway. Political elites thus continue to use the strategies of institutional change on display during the transitional governance period as they work to consolidate their preferred neopatrimonial political order in the aftermath of intervention. Second, the chapter recognizes that post-intervention Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan vary in the extent to which they can be characterized as peaceful, democratic, and well-governed. The governance qualities of the specific hybrid order that forms in each country rest on the particular system of rent extraction and distribution that emerges in each, which results, in turn, from how transitional governance interventions interacted with antecedent conditions in each case. The consequences of these peacebuilding attempts can only truly be understood when they are viewed as pivotal points in time.

Power dynamics evolve in ways that can be hidden unless enough time has elapsed to view their outcomes, especially when path-dependent feedback loops are involved.Footnote 4 The previous chapter emphasized that because UN peace operations must govern, they asymmetrically empower one group of domestic elites to dominate the transformative peace process and its aftermath. This has lasting consequences. Paul Pierson identifies five mechanisms through which power can beget power: the transfer of a stock of resources to victors; their subsequent access to a stream of resources over time; the signal that political victory sends about relative political strength and capability and the alignment of other actors to these signals; shifts in political and social discourse, or the cultural power to change society's preferences; and the inducement of preference changes that benefit those in power through targeted investments, institutions, and policies.Footnote 5 The evidence presented in this chapter shows that these mechanisms apply as much to those elites conferred power by the international community as to those who win it under their own steam.

Post-Intervention Cambodia: Exclusionary Neopatrimonialism and the Threat of Violence

The United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia declared victory and left the country having held free and fair elections in May 1993 and having overseen the process of constitution-drafting in the months that followed. On the ground, however, the power-sharing coalition between FUNCINPEC and the Cambodian People's Party that resulted from the 1993 elections created legislative and executive gridlock. The CPP continued to hold power across the organs of government and to administer the country just as it had before the elections, as the State of Cambodia, and, before UNTAC itself, as the Vietnam-installed regime known as the People's Republic of Kampuchea. The co-governing arrangement between Ranariddh and Hun Sen, nominally the first and second prime ministers respectively, was a fiction from start to finish. The latter wielded true power while the prince spent much of his time enjoying the perks of office and the two men intensified their competition to win power outright for their factions. Formal institutions and arenas of political contestation were stripped of meaning as they were used by Cambodian elites to do nothing more than mask the real political competition under the surface.

The power-sharing agreement concerned the top strata of government and, in practice, FUNCINPEC's authority was restricted to the cabinet level while the CPP retained its monopoly on administrative power exercised through the state hierarchy. In the ministries, FUNCINPEC found itself in a weak position – although it appointed many party functionaries to senior ministry and provincial positions, it simply lacked the bureaucratic capacity to have the necessary presence further down the hierarchy. Until 1993, FUNCINPEC had been a resistance movement rather than a political party and it proved unable to quickly develop any deeper institutional strength. In the provinces, FUNCINPEC-appointed governors and senior officials found that rank-and-file bureaucrats simply ignored their bidding and followed the instructions of their CPP leaders instead. Finally, the security apparatus was brought entirely under the control of the CPP and, increasingly, Hun Sen's faction within it – who portrayed the incorporation of the other Cambodian factions into political life as a threat to the nation.Footnote 6 Overall, the government bureaucracy and the military, ostensibly two organs of the state, became organs of the party. The CPP achieved this result by extending and strengthening the patron–client network within and among the state, party, and military apparatuses.

Continuing bureaucratic factionalism has prevented the development of national institutional capacity to this day. Institutions such as a neutral and effective bureaucracy, a nonpartisan army, an independent judiciary – let alone precedents for peaceful power transfer – have not taken root in Cambodia. A promising sign under UNTAC and immediately after the first election was the flourishing of NGOs and media outlets, and growing subnational political participation. UNTAC was innovative in helping to establish Cambodian NGOs dealing with human rights, democracy, and development, even giving them start-up advice and funding.Footnote 7 But these advances could not amount to much in the broader political environment.

In effect, it had already become clear by 1995–96 that the Cambodian political system fell far short of the pluralist, representative, accountable, and efficient government envisioned by the framers of the Paris Peace Agreement and the UNTAC mandate. Institutional capacity aside, Ashley points out that Cambodia's post-electoral power-sharing system did not emerge from, nor contribute to, the desire for reconciliation on the part of the country's elites and thus, unsurprisingly, did not lead to a political transformation of the type sought by the international community.Footnote 8 Not only did the power-sharing system fail to foster reconciliation among the factions and build a new political system based on compromise and inclusion. Worse still, the power-sharing system created dual governments as FUNCINPEC brought its supporters into the already bloated state structure. This deadlocked effective decision-making and governance and perpetuated parallel crony-based political networks. Having failed to secure electoral legitimacy or an administrative power base, FUNCINPEC leaders instead mimicked the CPP in rent extraction and distribution networks, entering into “a tenuous compact among competing patronage systems.”Footnote 9 The power-sharing system thus failed to foster true reconciliation among the factions. More perversely, it served in replacing outright elite conflict with a dual system of rent-seeking and predation. Operating both within and outside the state, these “[h]ierarchical patron–client networks…have expanded and subsumed the formal state structure.”Footnote 10

These patronage conditions have underpinned an ever-expanding dynamic of elite rent-seeking and rent distribution that undermines democracy and state capacity. The CPP and FUNCINPEC were united in their desire to protect their patronage resources and sought to ensure that their interests were not threatened through reforms. Both parties, for example, were anxious to ensure that their own supporters survived a process of civil service reform, which prevented a necessary retrenchment program; and attempts to modernize the public financial management system and increase state revenues also stalled since they were seen as a threat to the ability of the two patronage networks to extract off-budget rents.Footnote 11 The consensus principle of the coalition government endowed the CPP in particular, with its control of the state, de facto veto power over any reforms that threatened its political, financial, or institutional interests. The capacity of the state to deliver public goods and services had been weak under the State of Cambodia. Post-UNTAC administrative reforms became increasingly unlikely. The state had no nonpartisan, technocratic constituency to support institutional reform and the building of state capacity and to defend itself against the elite's desire to cement the patron–client networks upon which its popular support depended. UNTAC, in emphasizing elections over statebuilding, missed the window of opportunity to build that coalition for the reform and strengthening of the state, which, in turn, has hampered the international community's efforts to build state capacity and improve Cambodian governance into today.Footnote 12 Caroline Hughes observes that the government has, in particular, prevented development partners from having any real influence over the civil service, judiciary, and natural resource sectors in order to maintain these core elements of the administrative apparatus as “a sphere of discretionary political action and an instrument of political control.”Footnote 13 Measures of government effectiveness in Cambodia demonstrate that while state capacity may have improved slightly in the late 1990s, it has since declined and has stagnated at a relatively low level in comparison to its per capita income peers.Footnote 14

The capture of the state apparatus, a hallmark feature of neopatrimonial political order, doomed Cambodia to an inevitable backslide in terms of democratic consolidation and it also hampered statebuilding. UNTAC's failure to move the CPP toward depoliticizing the state structure was its true legacy for post-1993 Cambodia, having much more of an impact on the country's later course than UNTAC's success in holding elections. The international community lost the opportunity to build a countervailing locus of authority in the Cambodian state apparatus that could potentially prevail against a corrupt, violent, and cynical political elite and form the basis for a genuine political settlement to come out of peacebuilding through transitional governance. The power-sharing coalition, viewed by the international community as an encouraging move toward legitimate governance, was a mismatch for Cambodia's zero-sum, “winner-takes-all political culture.”Footnote 15 The consolidation of two parallel patron–client networks embedded in the state also affected internal party dynamics, concentrating power in the hands of Hun Sen and Ranariddh. The two leaders managed to work together for the first three years of their coalition government, avoiding contentious issues and pursuing enough economic liberalization to satisfy foreign reform demands. Indeed, Cambodia scholars have argued that the privatization and marketization reforms introduced in the country in 1989 made the expansion of dual party-based clientelist networks easier and more profitable.Footnote 16 In this regard, too, the international community's policy preferences enabled post-conflict elites to achieve their own objectives more effectively.

Yet, even as they cooperated in rent extraction and distribution, Hun Sen and Ranariddh continued to jockey for absolute power in the still-evolving political context. Tensions quickly mounted between the two leaders; by 1996, Ranariddh began to complain vocally about inequality in the coalition and the imbalance between the two prime ministers and their parties became increasingly obvious. The Khmer Rouge still managed to exert an influence on governance in the country even as a spent military and political force, when Ieng Sary, one of the faction's top leaders, announced that he would defect to the government and bring with him both a large proportion of Khmer Rouge troops and the resource-rich territory around his stronghold of Pailin. Hun Sen and Ranariddh, each eager to decisively tip the power balance their way, both offered large sums of money and the promise of future rent streams to entice Ieng Sary to join their respective sides. In the end, this was another political battle won by Hun Sen.Footnote 17

Anticipation of the 1998 national elections set off a series of events through which Hun Sen and the CPP were able to consolidate their political power. The three main opposition parties – FUNCINPEC, the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party, and the new reformist Sam Rainsy Party (SRP) – formed a coalition to contest the elections and challenge the CPP's grip on power. In turn, the CPP became increasingly concerned about the increased attractiveness to voters of the opposition coalition. Violence erupted in the charged political atmosphere when an opposition rally led by Sam Rainsy was bombed in March 1997. In July of the same year, troops loyal to Hun Sen and the CPP staged a coup d’état, bringing tanks onto the streets of Phnom Penh, skirmishing with and defeating royalist troops, and forcing Ranariddh, Sam Rainsy, and other non-CPP politicians into exile. Hun Sen's pretext for this move to oust Ranariddh from the political scene was the oft-invoked specter of renewed civil conflict, based on the accusation that Ranariddh was about to strike a reintegration deal with the Khmer Rouge. This coup marked the breakdown of the attempt to share power between elite groups and the emergence of a de facto one-party system led by the hegemonic CPP.Footnote 18

More broadly, the 1997 coup and the series of elections that have followed represent a sequence that has returned Cambodia to the often-violent, inherently undemocratic, and traditionally clientelist manner of asserting political order in the country. The expanding and tightening grip on Cambodia's administrative and political systems exerted by the CPP and Hun Sen has thwarted any meaningful progress in either state capacity-building or democratic consolidation. A new election was held in 1998 with the exiled politicians returning to Cambodia to participate after almost a year of post-coup negotiations and pressure from the international community. Yet FUNCINPEC and the SRP did not have the deep party roots at the subnational level that were necessary to challenge the CPP's organizational strength and claim to state authority across the country. In the announced election results, decreed free and fair by international observers, the CPP won a plurality, while FUNCINPEC and the SRP split the majority. (Official electoral results from 1998–2013 are presented in Table 5.1.) It was common knowledge that the CPP controlled this election, dominating new oversight institutions such as the National Election Committee and restricting opposition politicians’ access to the media.Footnote 19 In another ostensibly power-sharing arrangement, Hun Sen was renamed prime minister and Ranariddh was made the president of the National Assembly. Some space for the representation of opposition parties was made at subnational levels of governance, but the CPP continued its entrenched hold on the structures of the state. In practical terms, little changed “the view that FUNCINPEC and SRP representatives took part in government essentially on the sufferance of the CPP.”Footnote 20

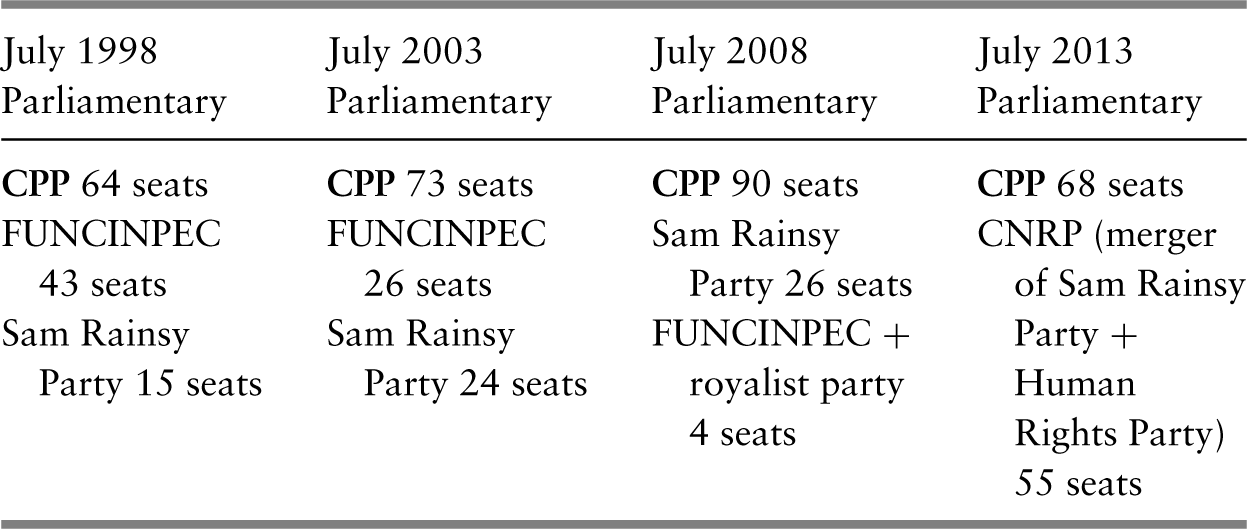

Table 5.1 Electoral results in Cambodia, 1998–2013

| July 1998 Parliamentary | July 2003 Parliamentary | July 2008 Parliamentary | July 2013 Parliamentary |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CPP 64 seats FUNCINPEC 43 seats Sam Rainsy Party 15 seats |

CPP 73 seats FUNCINPEC 26 seats Sam Rainsy Party 24 seats |

CPP 90 seats Sam Rainsy Party 26 seats FUNCINPEC + royalist party 4 seats |

CPP 68 seats CNRP (merger of Sam Rainsy Party + Human Rights Party) 55 seats |

This familiar pattern was repeated in the July 2003 elections: after an electoral process marked by voting fraud and violence, the CPP won over half the seats in the national assembly, although it did fall short of the two-thirds majority needed to form a government. One year of stalemate followed, with negotiations to form a government beginning in July 2004 and culminating in yet another deal on paper with FUNCINPEC. In practice, the control exercised by the CPP and Hun Sen on the country's levers of power simply became more concentrated, even as the CPP continued to gain a veneer of international legitimacy from these elections, which it has prided itself in organizing efficiently. Although international observers have certified all of Cambodia's series of post-conflict elections as free and fair, the CPP's electoral strategy is common knowledge: in 2003, its guidance to party representatives was to offer clear voting instructions and easy poll access for their supporters, combined with misdirection for other parties’ supporters.Footnote 21

Within a decade of UNTAC's withdrawal, the formal institutional and electoral space was simply no longer the true arena of political contestation. As he further consolidated political power, Hun Sen continued to strengthen the CPP's control over the state and its lucrative patronage networks. The CPP-dominated Royal Government of Cambodia has created and reinforced a system of resource generation and distribution for paying off rivals and supporters that runs parallel to the formal trappings of government through access to large off-budget “slush funds.” What should be public goods and services for the rural population – such as schools, health clinics, roads, and bridges – are branded as targeted “gifts” provided by the CPP and its senior leaders to the population, instead of being presented as programmatically delivered government outputs.Footnote 22 Villages across the country thus receive “Hun Sen schools” and health centers bearing the names of Hun Sen's wife and other prominent CPP elites. From 1998 onward, this particularist approach was a pillar of the CPP's electoral strategy and proved crucial in their increasing vote share in the 1998 and 2003 national elections and the 2002 and 2007 local elections. Through its clientelist strategy, the CPP has claimed for itself the mantle of being the only party that could effectively deliver public services – notwithstanding the need to rely on personal networks or bribes to access these services. In 2003, for example, the CPP's electoral message was, “We are the party that gets things done; don't bite the hand that feeds you.”Footnote 23

The patronage machine has also been indispensable to the processes of elite accommodation within the country – and has, in turn, freed the government and party elites, to a great extent, from the need to be accountable to the Cambodian population. With the CPP hegemonic, a “shadow state” system developed, with elites focusing on developing predatory and exclusive control over high-rent economic activity, thereby assuring their hold on power.Footnote 24 The army and police have been complicit in the patronage system, relying upon the valuable resource concessions they have been granted by the political elite to enrich individual officials and strengthen their bureaucratic power through an array of illegal and predatory activities.Footnote 25

Cambodia's political elites have expanded their patronage networks both vertically, to accumulate uncontested power at the subnational level, and horizontally, to include wealthy business interests and military leaders, who control, together with politicians in mutually beneficial arrangements, access to most of the country's lucrative natural resources, including timber and now oil.Footnote 26 An elite strata of Cambodian businessmen accrue rents in partnership with government and party officials, through channels such as preferred access to government procurement contracts and government-brokered land grabs in anticipation of lucrative development projects. Cambodian newspapers are filled with reports of protests about evictions in Phnom Penh and other towns.Footnote 27 Rural areas are also affected by this phenomenon: Hughes reports that what was a fairly egalitarian land-holding system in the countryside in 1989 was transformed into a highly unequal one by 2006, where 70 percent of the land was owned by the richest 20 percent of the population, resulting in a considerable “dispossession of the poor” in the context of the rural subsistence economy.Footnote 28 Overall, a process of privatization of state assets – forestry, fisheries, minerals, water, petroleum, and land – has generated revenues for the government to distribute as clientelist payments for political support; and has fortified a mutually symbiotic relationship between Cambodia's political and economic elites.

As these predatory patterns have increasingly permeated the country's political economy, the role of violence and intimidation in influencing election results gave way, for over two decades, to an increasing reliance on patronage distribution aimed toward uncontested political dominance. In this way, elite predation has replaced outright conflict as the main avenue through which Cambodians experience insecurity and vulnerability in everyday life – but “the threat of violence [remains] an ever present prop to the system.”Footnote 29 In addition to patronage distribution, the CPP's other core electoral strategy has been the mantra that it alone can ensure security and order in the country and prevent it from descending again into conflict; when, ironically, the only real insecurity in Cambodia emerges from within the CPP and as a result of its tactics. Hun Sen and other party leaders regularly raise the specter of renewed civil war in the event that the CPP's governing legitimacy were to be challenged. Yet the opposition persists – in the elections of 2013, even in the face of the typical widespread enticements for CPP voters and the intimidation of opposition supporters, Cambodian voters delivered surprising gains at the polls to opposition parties on the back of high levels of expressed discontent with poor government services, corruption, land grabs, and poor economic opportunity. Still dominating oversight and executive functions within government, the CPP persuaded Sam Rainsy and his new opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), to end a boycott of parliament and enter into a working relationship with the governing regime. By late 2015, what appeared to be a promising rapprochement had ended, with a bitter stand-off between Hun Sen and a newly self-exiled Sam Rainsy in full force. Opposition leader Kem Sokha marked the twenty-fourth anniversary of the Paris Peace Agreement in October 2015 by denouncing the CPP government for having failed to deliver on the promises set out in the peace deal.Footnote 30 Hun Sen, in turn, reverted to his dire warnings of the return of civil strife and violent conflict if voters fail to support the CPP.Footnote 31

It may be the case that the logic underpinning the neopatrimonial political order provided by the CPP in post-conflict Cambodia is in the process of changing from one of enforcing internal security to one in which the regime will need to deliver a greater measure of public services and some level of collective goods in order to retain political support for itself. The 2013 election results were viewed as a watershed in this respect, especially since the basis for the regime's legitimacy appears to be shifting as an older generation scarred by the civil war and genocide becomes superseded politically by a new generation with little direct memory of war and more modern demands of government. In 2014, it seemed that the CPP regime recognized that it would have to start doing something differently or else be at real risk of being voted out.Footnote 32 Perhaps, twenty-five years after the end of the Cambodian civil war, post-conflict incentives are finally being truly reoriented. In the immediate post-conflict environment, it was apparent that the time horizons were extremely short, orienting the country's elites toward high levels of extractive behavior – and even collusion if necessary, as evidenced in the CPP's and FUNCINPEC's dual rent networks. Now, with some degree of demand for accountability, government performance in terms of service delivery, and renewed attention to electoral legitimacy, the time horizon may finally be lengthening – and it appears likely that the CPP will have to better deliver some measure of public goods in order to get the minimal level of public support necessary to stay in power legitimately. If this were to become true, it will not have been the international peacebuilding intervention that achieved these results; the changes will have been the outcome of a more organic process of evolution in governance.

Post-Intervention East Timor: Inclusionary Neopatrimonialism and Latent Conflict

After East Timor attained independence, the UN designated two successive missions, the United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor (UNMISET, 2002–2005) and the UN Office in Timor-Leste (UNOTIL, 2005–2006), to assist with the program of continued reconstruction. The central dimension of both those mandates was to provide continued capacity-building assistance to the East Timorese administration. Although by September 2001, UNTAET had established the East Timor Public Administration as part of an all-Timorese transitional government, this embryonic civil service had only a very limited capacity. The civil administration was highly dependent on international assistance to make up for a low level of professional skills, particularly in the central government functions of human resources and public financial management.Footnote 33 Timorese political leaders’ emphasis on political incorporation had meant that little attention was paid to the state-strengthening dimension of the peacebuilding program. Measures of government effectiveness in East Timor demonstrate that state capacity did not much improve after the transition to independence and has remained at low levels.Footnote 34

FRETILIN's domination of the political process after the transitional period – facilitated by UNTAET's slow moves to incorporate broader political participation and the sequencing of the Timorization of government – proved problematic for the strengthening of the state and the longer-term consolidation of democracy in East Timor. FRETILIN, in essence, “placed the new National Parliament in clear subordination to a government intent on using its majority to push through its ambitious legislative program.”Footnote 35 It also quickly began to consolidate its patronage networks throughout the country by politicizing civil service hiring in district administration, ensuring positions were filled by FRETILIN cadres.Footnote 36 By mid-2005 it became apparent that, notwithstanding its grassroots support and dominating organizational presence throughout the country, the population at large did not necessarily share FRETILIN's goals for the country.

The FRETILIN leadership's particular history and contemporary policymaking style and content increasingly compromised the party's political legitimacy. The party compounded a pattern of Timorese elitist political behavior that threatened true democratic consolidation. In an oft-cited example of what was viewed as the FRETILIN leadership's political tone-deafness and elitist orientation, it chose Portuguese as the official national language, marginalizing the Indonesian-educated and Bahasa-speaking urban youth who were in the process of forming their own increasingly significant political constituency. Timorese civil society representatives have criticized the country's hierarchical and closed political culture, pointing out that although it may have contributed to the success of a national resistance movement it has since been detrimental to democracy.Footnote 37 The opposition began to mobilize – the Catholic Church, for example, began to take on a more activist and populist role, opposing the government over certain pieces of legislation.Footnote 38

Politically motivated violence erupted in April 2006, reflecting deep and long-standing political animosities among the elite, emerging state capture and competing patterns of patronage behavior, and an absence of elite efforts to engage with community and customary forms of governance.Footnote 39 This conflict turned violent as FRETILIN proved unable to assert legitimate control over armed groups – the breakdown in authority resulted in an episode of arson and looting in Dili and its environs. Over the course of several months of severe political instability, 38 people were killed and 69 wounded, 1,500 houses were destroyed, and 150,000 people were internally displaced.Footnote 40 Eventually, the majority of the population had their wishes fulfilled when FRETILIN Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri was forced out of office at the behest of Xanana Gusmão and other revolutionary leaders.

The 2006 conflict marked the onset of internal strife and political instability, distinct from both the decades-long resistance and the 1999 conflict associated with the independence vote. It revealed deep-seated social tensions in East Timor and some saw it as an outcome of UNTAET's failure to broker a domestic political settlement at independence.Footnote 41 The “crisis,” as it became known, was triggered by rising tension between factions in the armed forces and police. There was some truth to the notion that this dispute reflected long-standing animosities between the Western and Eastern factions within the armed forces – more Western commanders were killed during the Indonesian occupation and Western soldiers complained that their treatment under mostly Eastern commanders was unfair. The tension was a concrete manifestation of decisions made during the transitional governance period: when the East Timor Defense Force was created at independence, the first of its two battalions was recruited from the ranks of the FALINTIL guerrilla fighters in a process that disproportionately favored Gusmão loyalists and troops from the eastern districts of the country.Footnote 42 Some of this tension was also the outcome of political intrigue: the Minister of the Interior Rogério Lobato, with the implicit consent of Alkatiri, established loyalist groups inside the armed forces as a counterweight to those troops loyal to Gusmão. A UN Security Council assessment mission found that Lobato also supplied an irregular paramilitary group involved in the violence with arms intended for the police and that he instructed the group to use the weapons against political opponents.Footnote 43 Yet the crisis quickly spiraled to encompass a number of sociopolitical grievances and dimensions – escalating because it became a vehicle for key groups, particularly resistance veterans and Dili residents, to rally against the unpopular Alkatiri government.Footnote 44

Overlaid on the political scene was the fact that during this period East Timor had rapidly become one of the most petroleum-dependent countries in the world, with oil and natural gas revenues providing about 90 percent of government revenues, on average, since petroleum production commenced in 2004. In retrospect, observers point to the role played by petroleum revenues in lubricating the 2006 civil conflict and political fight.Footnote 45 At the time of independence the FRETILIN government had to operate with a very small budget and refused to borrow to finance more spending. As the country began to reap its first hydrocarbon revenues in 2004, the opposition disapproved of the continued austerity measures in the face of this windfall. By 2005–06 FRETILIN's decision not to spend the country's petroleum wealth to relieve poverty, kick-start growth, and create much-needed employment had contributed substantially to the population's widespread disaffection with the party.

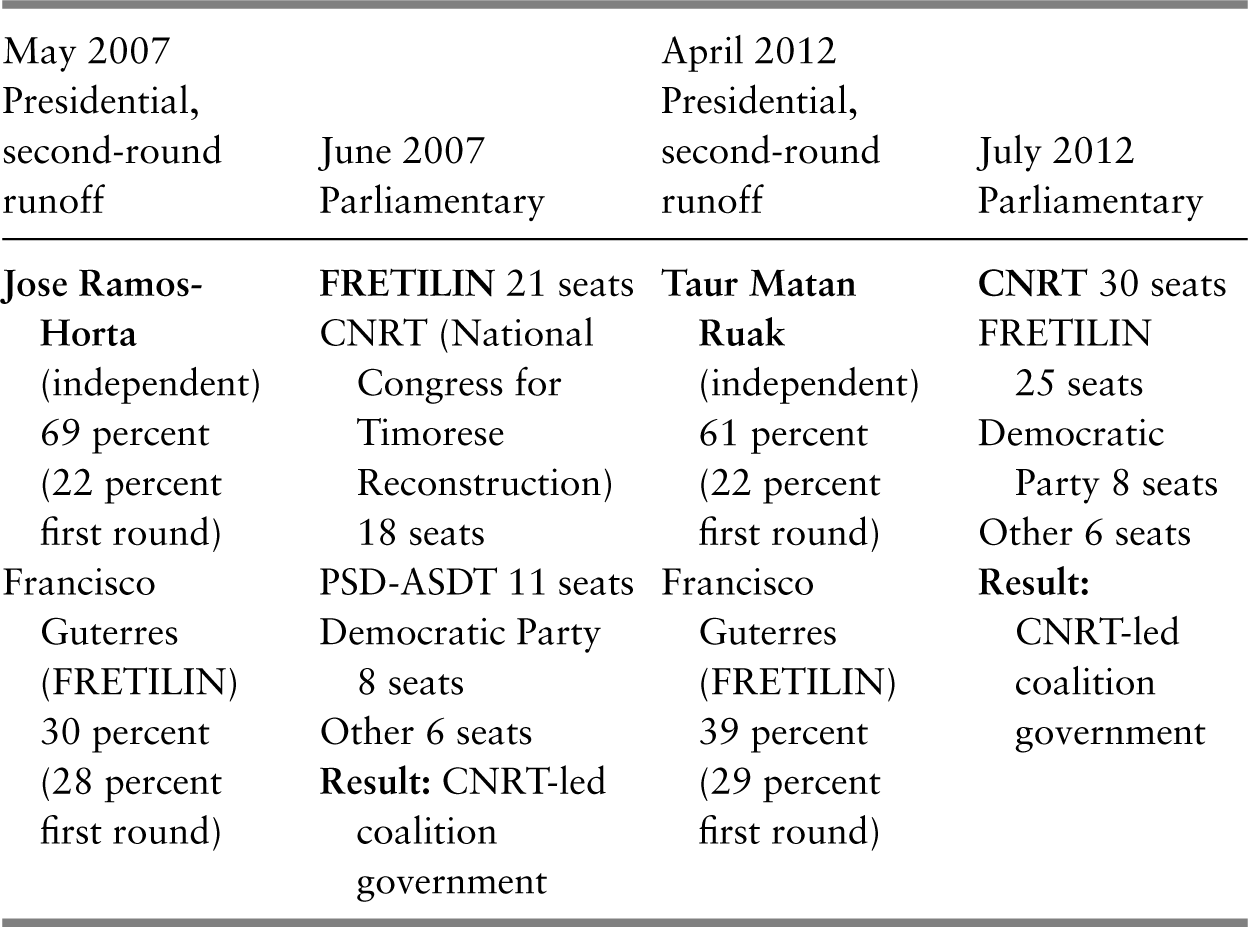

New presidential and parliamentary elections were held in May and June 2007, respectively. Xanana Gusmão stepped aside as president to run for prime minister, the real seat of power in the country, and his ally José Ramos-Horta easily won the presidential election against the FRETILIN candidate. In the parliamentary elections, FRETILIN received the largest number of votes but, in a serious rebuke from the voters, it saw its tally slip from 57 percent in the 2001 elections to 29 percent and it was unable to form a coalition government. (Official electoral results from 2007–2012 are presented in Table 5.2.) Gusmão's new National Congress for the Reconstruction of East Timor or CNRT – conveniently the same acronym of the enormously popular national resistance front under whose banner the independence referendum was won in 1999 – won 23 percent of the vote, the next highest share after FRETILIN's. In a contentious decision, President Ramos-Horta exercised his constitutional right in selecting the CNRT to form the new government – but Gusmão was only able to do so at the head of a volatile new coalition.Footnote 46

Table 5.2 Electoral results in East Timor, 2007–2012

| May 2007 Presidential, second-round runoff | June 2007 Parliamentary | April 2012 Presidential, second-round runoff | July 2012 Parliamentary |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Jose Ramos-Horta (independent) 69 percent (22 percent first round) Francisco Guterres (FRETILIN) 30 percent (28 percent first round) |

FRETILIN 21 seats CNRT (National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction) 18 seats PSD-ASDT 11 seats Democratic Party 8 seats Other 6 seats Result: CNRT-led coalition government |

Taur Matan Ruak (independent) 61 percent (22 percent first round) Francisco Guterres (FRETILIN) 39 percent (29 percent first round) |

CNRT 30 seats FRETILIN 25 seats Democratic Party 8 seats Other 6 seats Result: CNRT-led coalition government |

A precedent for the peaceful transfer of power was thus set relatively early in East Timor's post-conflict years. Yet this was still a government where authority was concentrated in the hands of a small group of revolutionary-era political elites. The crisis had also clearly thrown the country into a serious constitutional and political crisis, the resolution of which was not uncontentious. For example, observers criticized Gusmão for having initially compromised the constitution by demanding Alkatiri leave office; yet there is no legal process in East Timor for determining the constitutionality of his actions as president. There appeared to have been a reversal of some degree of earlier behavioral democratic consolidation among core political elites – but public attitudes toward democracy remained encouraging. In a more promising sign of renewed political institutionalization, smaller parties were proliferating and growing in strength, capitalizing on the frustration of young, urban, and educated East Timorese with the older, Portuguese-speaking, conservative leaders of FRETILIN and attempting to better channel the political participation of the East Timorese population. On the statebuilding front, the insistence on political participation and development on the part of both the UN and the Timorese elite continued to overshadow responsibility being undertaken for reconstructing the still-eviscerated structures of state. Although the formidable statebuilding challenge may have been obscured by the attempts to repair the country's fragile democracy, the lack of attention to institutional and human capacity-building contributed in no small part to the political instability experienced in 2006.

Under the Gusmão-led coalition government, the neopatrimonial nature of politics in East Timor has become increasingly apparent. Political elites began to benefit from the oil price spike and the significant stream of petroleum revenues in the late 2000s, distributing the patronage made possible by these fiscal receipts and gaining political support on that basis. East Timor thus began to follow a pattern familiar to rentier states, with public sector hiring and pay increasing along with growing concerns over elite capture of petroleum concessions and lucrative procurement contracts.Footnote 47 The new governing coalition viewed the Timorese population's dissatisfaction upon failing to see some immediate benefits emerging from the country's newfound peace and its petroleum wealth as a key dimension in the downfall of FRETILIN. The electoral campaign run by Xanana Gusmão's CNRT thus pledged to increase social spending rapidly in order to deliver a peace and petroleum dividend. Once in office, Gusmão's administration delivered on that promise by initiating social transfers to specific groups in the population and opening up decentralized mechanisms for rapidly increasing public infrastructure spending – with immediate and sustained results. Capital spending climbed from less than $25 million in 2005 to about $180 million in 2008 and $600 million in 2011.Footnote 48 Cash transfers constitute a very large share of the budget – $234 million, or 13 percent of the 2012 budget, and a great deal more than the $153 million spent on the health and education sectors.Footnote 49 These spending increases were made possible through the government's repeated annual requests to Parliament to exceed the legally prescribed level of petroleum revenue spending established to prevent the short-term squandering of resource wealth.Footnote 50

In short, since the 2007 elections, it has become both legitimate and relatively easy for the government to engage in the neopatrimonial distribution of ever-higher shares of the country's petroleum rents. Viewing the various public spending measures in the best possible light, the new coalition government acted in the aftermath of the 2006 crisis to “buy the peace” with the country's best interests in mind. From this viewpoint, the government fulfilled its campaign promises and perceived mandate to distribute rents in the form of public expenditures to key constituencies – thereby maintaining post-election political stability by pacifying the social dissent and controlling the internecine elite conflict that had together led to the 2006 crisis. A preliminary analysis of the geographic allocation of public spending in East Timor found that the government was spending more – in terms of both cash transfers and public investment allocation – in those districts most strongly supportive of the coalition partners in the 2007 election.Footnote 51 The coalition was rewarded with another victory in the 2012 elections, in which FRETILIN failed to make an expected comeback in the polls; and there has been no return to widespread conflict since 2006.

Yet this is an equilibrium underpinned by a neopatrimonial political order, rather than the effective and legitimate governance envisaged by the international community and the major UNTAET intervention. A small group of political–economic elites has cemented its place in authority by dispensing patronage in exchange for broad political support. The coalition government, for example, has targeted its major clientelistic practices to very deliberately and very successfully co-opt the veterans of the clandestine resistance. High-level veterans are best understood as being still-armed militia leaders who represent a substantial threat to political stability. They are the specific individuals dispersed throughout the country who still have the capacity – and, if their demands are unmet, the expressed willingness – to mobilize civil conflict and even violence against the regime.Footnote 52 Of the aggregate spending on cash transfers, $85 million – a full 5 percent of the total 2012 budget – went to veterans.Footnote 53 The official annual veteran payment averaged just under $3,200 per beneficiary in 2011, representing 137 percent of the Timorese average total household budget.Footnote 54 These transfer payments to veterans have been framed as recognition for past service to the country rather than as a form of social assistance and outpace and crowd out other social spending. Veterans have also been explicitly targeted as the beneficiaries of the government's decentralized public investment efforts. Several interviewees in 2013 urged me to imagine the counterfactual – asking, in particular whether political stability would have persisted had major patronage distribution through government spending channels not been initiated and targeted to veterans.Footnote 55

A different dimension of the neopatrimonial political order has manifested itself at the national level, through elite rent-seeking and the capture of significant elements of the government's public investment program and recurrent public sector contracts. In contrast to the distribution of government spending to different groups of the population, this latter channel of rent distribution benefits only an extremely small and concentrated political–economic elite and their clients. Reports abound of well-connected contractors – especially the family members and business partners, both Timorese and foreign, of senior government officials – winning single-sourced contracts, in contravention of the procurement law, with extremely high profit margins.Footnote 56

This type of predatory rent capture by elites is a typical rentier state syndrome – but the East Timor experience exhibits an interesting twist. During the term of the first coalition government from 2007 to 2012, there was the sense that individuals and companies with particular ties to the coalition partners were capturing the lion's share of the contracts, thereby excluding those connected with the opposition from the lucrative rent streams. Since the government's re-election in 2012, however, there have been signs that opposition elites are also being incorporated into the system of rent-sharing. In one sign of this increasingly collusive elite behavior and capture of petroleum rents, the CNRT government and FRETILIN opposition in February 2013 came to a budget agreement behind closed doors that led to an unprecedented unanimous budget vote in Parliament. Many surmised that the implicit quid pro quo for the opposition's agreement was their increased access to rents through preferred procurement channels.Footnote 57 As in Cambodia, it appears that neopatrimonial practices may be as important, if not even more important, to establishing inter-elite compromises and accommodation as they are to bolstering popular support for the governing party and the reigning political order. At the same time, the Timorese population has also demanded cleaner and more efficient government. In February 2015, Gusmão stepped aside as prime minister to make way for a new generation of leadership. In a sign of a continuing thaw in elite political rivalries – combined with a move toward a more technocratically inclined executive – Gusmão and his ruling CNRT party recommended FRETILIN member Rui de Araujo, the country's successful health minister at independence, to be prime minister.

Elite collusion in neopatrimonial governance is unsurprising in the context of East Timor's contemporary political history. Leaders across the political spectrum in the small country come from a small slice of society – being primarily drawn from three main groups: the mestiço elite; smaller groups of Indonesian-Chinese-affiliated businessmen; and a handful of “Timorese–Timorese” leaders of the clandestine resistance, many of whom come from indigenous royal houses. The current generation of leaders for the most part grew up together while attending one of two major Portuguese seminaries near Dili; divided themselves into opposing factions in the 1975 civil war; and then came together again, albeit playing diverse roles, during the resistance and the post-independence UN transitional period. Their political–economic incentives are, for the most part, aligned – especially in the context of the relatively short time horizons in place as a result of the known end circa 2022 of the revenue stream from the country's only operational major gas field and the projected depletion at current spending rates of the country's petroleum revenues by 2028.Footnote 58 The number of politically and economically powerful families in East Timor has certainly multiplied since independence, with the Indonesian–Chinese-affiliated group particularly in the ascendant. Nevertheless, the core political–economic elite in East Timor represents, in essence, a very small winning coalition necessary to remain in power.Footnote 59 Over the past five years, moreover, through a deliberate neopatrimonial strategy, this elite has elicited and reinforced the political support of the only real potential spoilers, veteran leaders, by distributing just enough of the gains to pacify dissent and secure an element of legitimacy across the country.

Post-Intervention Afghanistan: Competitive Neopatrimonialism and Persistent Insecurity

The inauguration of the new Afghan national assembly on December 19, 2005 marked the official conclusion of the Bonn peace process as Afghanistan met its milestones. UNAMA's role in the aftermath of the Bonn process was to support the new government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in its various dimensions of peacebuilding, including the identification of a new security framework, the improvement of governance, and the promotion of development. A new roadmap, known as the “Afghanistan Compact,” was drawn up at the London Conference on Afghanistan held in early 2006. At this gathering over sixty countries and international agencies committed themselves, in partnership with Afghan government leaders, to the principles and targets laid out in the Compact, which was to guide the international community's support to Afghanistan in state capacity-building and the institutionalization of democracy. The express goal of the compact was to rely more heavily on Afghanistan's nascent institutions, with pledges of financial support from the international community.

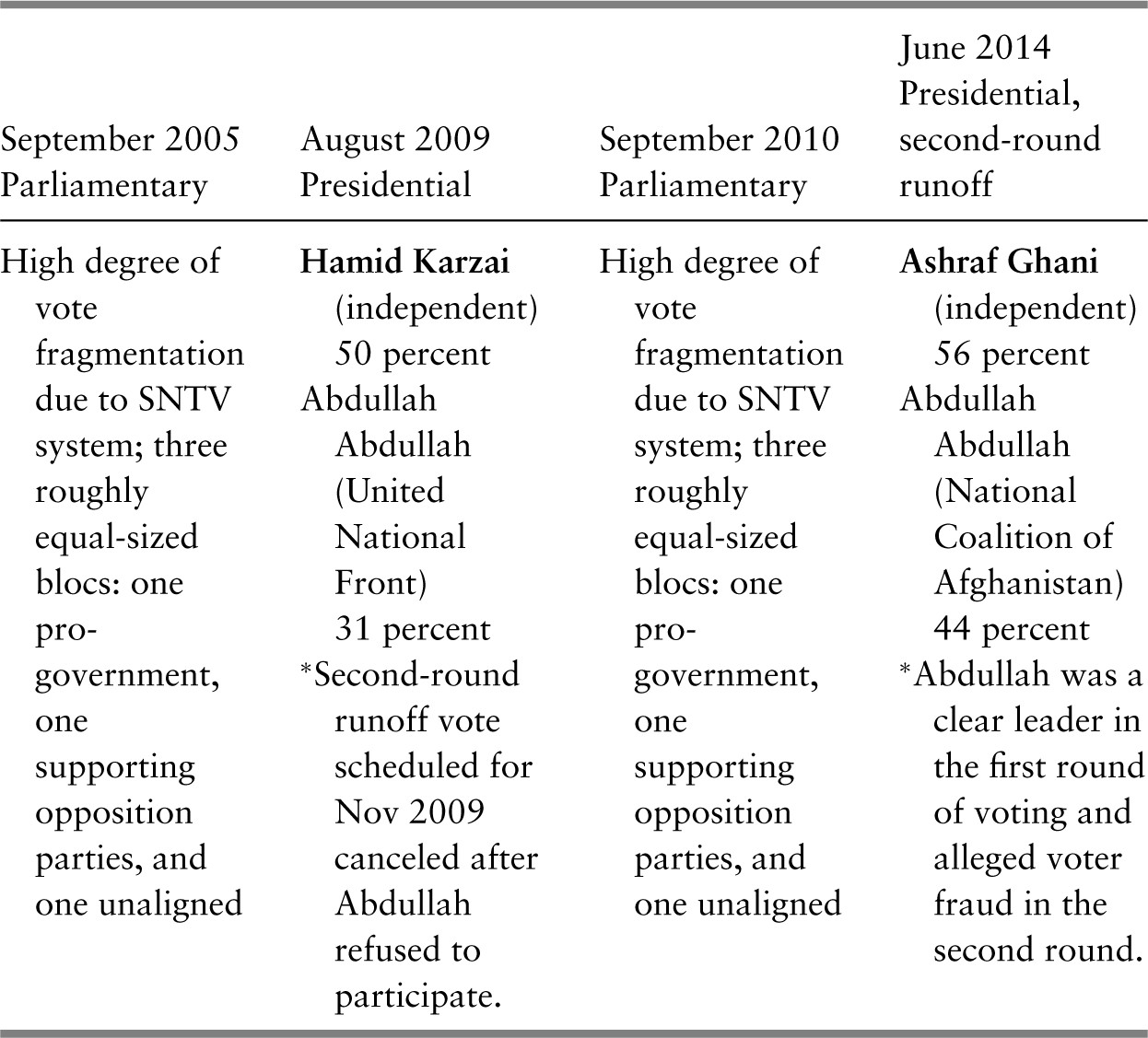

Political stabilization, implicitly the international community's overarching goal in Afghanistan, has proceeded in fits and starts. Many have guessed that the fragmented parliament that resulted from the single non-transferable voting system adopted for the 2005 parliamentary elections was what Karzai intended in order to keep the executive stronger than the legislature: the elections led to three roughly equal-sized blocs in the assembly – one pro-government, one comprising the opposition parties, and one unaligned.Footnote 60 Even for the supposedly empowered executive, however, a fragmented parliament can make the formation of government and legislative politics very hard to handle. Legislative gridlock is undesirable everywhere and in post-conflict situations can even be dangerous given the immediate need for effective governance to underpin political stability. Constitutional experts consider a stable party system to be an asset in post-conflict democracies. The SNTV system typically impedes party-building, making electoral alliances personality-driven and beholden to regional and other particularist power bases rather than being formed on the basis of programmatic and collectivist appeals articulated by ideologically coherent parties. The parliamentary fragmentation induced by the SNTV system impeded Karzai's reform agenda, since in practice it meant that for each executive initiative he had to assemble anew a legislative coalition through piecemeal deals and logrolling.Footnote 61 Moreover, since Karzai was unable to maintain a coalition of support for his program, the Afghan parliament was able to assert itself vis-à-vis the government. In May 2006, for example, the legislative body approved most of Karzai's proposed cabinet – but only after refusing to rubberstamp the whole body and insisting on individual hearings for each member.

Power tussles with parliament aside, Karzai acted to make the cabinet more his own by dropping the powerful trio of Panjshir Valley leaders who dominated the political and military scene after the Taliban's defeat and finally freeing himself from accusations that his government was under the control of the Northern Alliance faction. The move was seen as a step away from the “compromise government” that Karzai and his foreign allies built initially as a power-sharing mechanism. Later iterations of the cabinet included more technocrats as well as some remaining leaders of ethnic and political groups from around the country. Bringing local leaders to govern in the capital had the added benefit of neutralizing their influence in their regional strongholds. Thus, in the mid-2000s, it seemed that the Karzai administration was making progress in curbing the most egregious displays of patronage – for example, by moving Ismail Khan out of the governorship of Herat and into the post of Minister of Energy and Water, by demoting Gul Agha Shirzai from the governorship of Kandahar province to that of Nangahar province, and by removing Marshal Mohammed Fahim from his post as defense minister. By later in the decade, however, more ominous patterns of neopatrimonialism had asserted themselves.

Core choices made about Afghanistan's institutional architecture during the Bonn process and under UNAMA's supervision have had lasting effects on both state capacity-building and democratic consolidation in the country. Analysts have argued that the international community's preference for a “broad-based,” compromise government over the course of the Bonn political process had the drawback of setting aside the pursuit of federalism, which many believed would have been a more natural fit for delivering public services and building governing legitimacy in the ethnoregionally diverse country. Federalism proponents argued that political contestation could have been transferred fruitfully to places other than Kabul, thereby recognizing the true loci of power – military, political, economic, and administrative – in the country. In attempting to create a strongly centralized national-unity government – which grew, in turn, out of UN efforts to solve the civil war dating back to the 1990s – critics argued that the international community fell prey to wishful thinking rather than designing appropriate institutions for the fissiparous reality of Afghan politics.Footnote 62

Others have maintained that the appropriate solution to state collapse in Afghanistan was indeed a centralized state that could build effectiveness and maintain a credible monopoly on violence. In this view, decentralized or federal systems create insurmountable center–region tensions.Footnote 63 The highly centralized, unitary state model was intended to bring the provinces, once and for all, firmly under Kabul's political, administrative, and financial control – something that had not been achieved in modern Afghanistan. Many Afghan policymakers and observers themselves preferred the strong central state model, believing that persuading local strongmen to incorporate their power bases into a Kabul-led statebuilding process was an effective way to neutralize their extralegal power, and that decentralization or devolution could come later if still desired. Amin Saikal, for example, emphasized that meaningfully incorporating Afghanistan's “micro-societies” into the new fabric of the state was essential but possible within either a centralized or devolved state structure.Footnote 64

One of the key aims of the broad-based coalition idea advocated by the international community was to ease fears that Pashtuns, who accounted for two-fifths of the Afghan population, making them the largest single ethnic group, would grow too strong. Pashtuns, on the other hand, believed that the concept of broad-based government was actually “code for rule by non-Pashtun figures from the old anti-Taliban coalition, the Northern Alliance,”Footnote 65 and that the Interim and Transitional Administrations overly represented these other groups. During the transitional period precisely the ethnic dynamic that national unity government proponents were trying to avoid was set in place, whereby Pashtuns, with the encouragement of Karzai, reasserted themselves politically and aroused the suspicions of Afghanistan's other major ethnic groups. The October 2004 presidential elections took on a significantly ethnic cast as a result of this ethnic electioneering, with Tajik, Hazara, and Uzbek leaders leading the vote in provinces dominated by their own ethnic groups.

In a promising sign for political institutionalization, some of these leaders – the Tajik Yunus Qanooni and the Uzbek Rashid Dostum foremost among them – would later form political parties in the run-up to the September 2005 parliamentary elections in order to broaden their appeal across ethnic lines. Despite the reluctance of Karzai and other senior officials to see the formation of parties for fear that they would deepen ethnic divisions, more than fifty parties registered prior to those elections. A few months ahead of the parliamentary elections, Qanooni announced the formation of an opposition front to compete in the elections, intended to forge a serious opposition bloc to Karzai's government.Footnote 66 Such moves toward party-building and other elements of political institutionalization could represent important advances in terms of behavioral consolidation of democracy among core political elites.

Yet the perception of corruption and personal empowerment and enrichment has also been a constant in the narrative of contemporary Afghan democracy. In August 2009, Hamid Karzai failed to secure an outright majority in the presidential election, being dogged by accusations of corruption in his administration and concerns about his attempts to secure victory by allying with unsavory warlords with documented human rights abuses. He nonetheless won re-election when the runner-up, Abdullah Abdullah, refused to participate in the second-round run-off due to widely acknowledged problems of voter intimidation, media censorship, and electoral fraud perpetrated by government supporters. (Official electoral results from 2005 to 2014 are presented in Table 5.3.)

| September 2005 Parliamentary | August 2009 Presidential | September 2010 Parliamentary | June 2014 Presidential, second-round runoff |

|---|---|---|---|

| High degree of vote fragmentation due to SNTV system; three roughly equal-sized blocs: one pro-government, one supporting opposition parties, and one unaligned |

Hamid Karzai (independent) 50 percent Abdullah Abdullah (United National Front) 31 percent *Second-round runoff vote scheduled for Nov 2009 canceled after Abdullah refused to participate. | High degree of vote fragmentation due to SNTV system; three roughly equal-sized blocs: one pro-government, one supporting opposition parties, and one unaligned |

Ashraf Ghani (independent) 56 percent Abdullah Abdullah (National Coalition of Afghanistan) 44 percent *Abdullah was a clear leader in the first round of voting and alleged voter fraud in the second round. |

Even in the face of elite acrimony around elections, the consolidation of democratic attitudes among the Afghan public showed early signs of progress, in that Afghans quickly embraced the concepts of elections and democracy. Over the course of successive elections, voter turnout has remained quite high, although it fell from 84 percent in the 2004 presidential election to just about 60 percent in the 2014 presidential election, in part due to increased Taliban intimidation in the run-up to the latter. Richard Ponzio's 2005 public opinion survey also found significant internalization of democratic norms.Footnote 67 But, in a sign that power is still bifurcated between formal and informal, Afghans’ voting behavior does not necessarily match with their views on where power lies in their society. Ponzio's survey data also revealed that religious leaders were seen as having the most power and influence in local communities, followed by roughly equal perceptions of militia commanders, provincial and local government administrators, and tribal leaders, with elected officials coming in a relatively distant last in power and influence perceptions.Footnote 68

The need to neutralize or incorporate alternative loci of power in the political system continues to be the major obstacle besetting both statebuilding and democratic consolidation in Afghanistan. While provincial governors and district officers are appointed by the center, most governors received their posts in the interim, transitional, and subsequent administrations because of their independent and traditional power bases. Andrew Reynolds noted that of the 249 legislators elected to the first national assembly 40 were commanders still linked to militias;Footnote 69 moreover, nearly half of all the original crop of MPs were mujahideen veterans of the war against the Soviets in the 1980s.Footnote 70 The persistent and instrumental patron–client culture associated with the militias has yet to be replaced by government and civil society institutions that offer public services in an accountable and programmatic manner. A frequent complaint of Afghans living in Kandahar, for example, is that life has reverted to the chaos under warring mujahedeen factions.Footnote 71

Most subnational leaders, initially appointed in recognition of their power and granted renewed legitimacy through the transitional governance process, have further entrenched their predatory activities and bolstered their patronage networks. These warlords have developed sophisticated political–economic strategies to sustain their power bases, managing their own resources and position in regional economic networks, both licit and illicit, while also tapping into international support.Footnote 72 Dipali Mukhopadhyay notes, however, that there is important variation in terms of the behavior of local strongmen and their strategy for governing provincial areas, when granted formal power by the central government to do so.Footnote 73 She observes how some of the government's most formidable would-be competitors, the regional warlords, have turned into valuable partners in governing the country and establishing a political order that, albeit suboptimal in comparison to the modern political order sought by the international community, is certainly better than what came before. Even as they practice traditional clientelist politics, some local strongmen are delivering an important measure of provincial governance on that basis.Footnote 74

The political accommodation choices made over the course of the Bonn process exposed two major political consolidation challenges in Afghanistan. On the one hand, the Karzai government has not been able to extricate its reliance – sometimes problematic, sometimes surprisingly beneficial – on the successful warlords, among the winners at the end of the conflict, who have since posed problems for the representativeness of democracy and the legitimacy and authority of the central government. On the other hand, the political process in Afghanistan has been unable – because of the unwillingness of successive Afghan governments and their foreign backers – to incorporate the Taliban, the losers of the conflict. Violent clashes increased in the run-up to the 2004 and 2005 elections, with Taliban militants stepping up attacks against soft government targets, particularly in Afghanistan's majority Pashtun southern and eastern provinces; these intensified again around the 2009 and 2010 elections.

These attacks increasingly undermined the government's legitimacy and, by the end of the decade, the steadily mounting clashes also compromised the government's authority, resulting in large swaths of territory in those provinces being ceded to the control of the Taliban and its allies. In short, the question of how to handle the Taliban re-emerged with pressing urgency after 2006, when the movement stepped up its campaign of instability and attacks against the governing authorities, both central and provincial. The Bonn Agreement was clearly a winners’ deal – but it was not necessarily the case that the longer-term political arrangements that emerged from the transitional process had to exclude the Taliban. By 2007, the Karzai government was holding informal talks with Taliban insurgents about bringing peace to Afghanistan, yet neither side has met the other's conditions to begin formal peace talks.

The challenges of political consolidation and government effectiveness that resulted, in part, from the narrowness of the Bonn peace deal threatened the stability of the Karzai government on dual fronts. While the deal itself probably needed to be narrow to be struck, the Bonn process and international involvement subsequently continued to constrain the outcomes of the political transition in specific ways, especially because the United Nations and the United States were concerned with political expediency and having a government counterpart they could rely on. One manner in which both the warlord and the Taliban problem could have been dealt with outside the political process would have been through a substantial, focused effort on structuring a political economy as well as a political and civil society arena in which the benefits of participation were clearly more rewarding than continued opposition. Afghanistan has the ingredients for a robust and vibrant civil society, made up of interlocking layers of tribe, religion, ethnic, and linguistic networks – what Saikal terms “micro-societies.”Footnote 75 The transitional governance process through which the international community instinctively pursued political stabilization failed in many ways to tap into the sources of legitimacy embedded in these micro-societies in a meaningful manner in order to leverage their salience and their power for central governance purposes.

Instead, it seems clear, as Hamish Nixon and Richard Ponzio argue, that the international community's peacebuilding strategy “resulted in the privileging of elections and institutions – however fragile and ill-prepared – over a coherent and complete vision for statebuilding and democratization.”Footnote 76 Nixon and Ponzio observe that key international players, including the United States, and Karzai wanted power strengthened in the president's hands in order to be able to co-opt or defuse regional strongmen – hence, in order to fulfill political stabilization goals, the parliament was deliberately kept weak and the broader democratization and statebuilding agendas were adversely affected. They provide another example with the story of the Provincial Councils, which are intended to provide local representation and bottom-up development coordination and planning. Although these have been hailed as an essential part of the Afghan statebuilding process, they have yet to be endowed with the resources or competency to perform their stated functions.Footnote 77

Progress on the statebuilding front has proven even more disheartening, although this is perhaps unsurprising since political stabilization was prioritized regardless of its longer-term impact on state capacity or effectiveness.Footnote 78 Measures of government effectiveness in Afghanistan demonstrate that state capacity may have improved somewhat in the last few years of the Taliban regime and the first few years of international presence, the latter probably due to the large amounts of service delivery and even central governmental functions carried out by aid organizations, but government effectiveness declined quite quickly once international attention drifted away from the country and it remains extremely low to this day.Footnote 79 A key measurable dimension of state capacity is the government revenue to budget ratio, an indicator of the ability of a state to finance its governing priorities and activities. In Afghanistan, Astri Suhrke reports, the government's 2002 tax revenue was less than 10 percent of the national budget and there was no change by 2004–05, when domestic revenues were expected to cover only 8 percent of the total national budget and the gap to be financed by donor funds; furthermore, this pattern was projected to continue for five years.Footnote 80 Based on this heavy dependence on external resources, Suhrke goes so far as to diagnose Afghanistan as a rentier state. Continued reliance on these external aid flows, no matter how efficiently handled, hampers the government's ability to strengthen its own legitimacy and authority vis-à-vis the population. Moreover, the Afghan government did not have the capacity necessary to absorb large inflows of aid – much of the money went to financing international consultants, who were not focused on transferring skills to their few Afghan counterparts and hence did not contribute to long-term capacity-building in the Afghan government.

Recognizing the immense reconstruction challenges still ahead of the country at the close of the Bonn process, the Afghan government and international donor community signed the Afghan Compact in December 2006. This strategy framed international assistance, tying it to government planning over five years; and follow-up meetings have since been held. In an equally promising development, alternative visions have begun to emerge in the country as the government attempts to continue the logic of the Bonn process. An opposition group formed in April 2007, the National Front, called for changes to the constitution to elevate the post of prime minister to share governance responsibilities with the president and demands direct elections of provincial governors, who are currently appointed by the president. This new opposition front, which included some members of Karzai's cabinet, formed to challenge the president amid growing frustration with his rule and the government's progress.

A decade after the conclusion of the Bonn Process, however, the deep elite power struggles at the heart of Afghanistan's political instability persist, continuing to manifest themselves in a center–periphery contest over political order and stability. Early successes in constitution-making and elections through the transformative peacebuilding approach gave way to a deteriorating security environment and setbacks in the international community's pursuit of modern political order in the country. Many hoped that the 2014 presidential elections would mark a turning point for post-conflict Afghanistan, as it began the transition away from Karzai's weak and fractious regime, which was also regarded as increasingly petulant in the eyes of the international community. The new president, Ashraf Ghani, is viewed widely as a modernizing technocrat. Yet the 2014 presidential election was, like the one preceding it, marred by widespread allegations of voter fraud and intimidation. Abdullah Abdullah, the Northern Alliance leader and then foreign minister under Karzai, was a clear leader in the first round of voting and insisted that he was the victim of large-scale electoral fraud in the second round – an assertion later confirmed by European Union election monitors. The standoff threatened to boil over into violence until the two politicians eventually came to a co-governance compromise, with the Pashtun Ghani taking the presidency and the Tajik Abdullah assuming the newly created position of the government's Chief Executive Officer.

Since taking office, however, Ghani has acted to centralize power in the office of the presidency, marginalizing both Abdullah and his own vice president, the Uzbek warlord Rashid Dostum. Albeit in the guise of fighting endemic administrative corruption, Ghani has undermined state capacity in several ways. He has, for example, brought billions of dollars of government procurement under the direct purview of his office, bypassing the line ministries that are supposed to handle this state business; his aides, too, are taking policy formulation and implementation into their own hands, sidelining appointed officials. Even those who support Ghani's consolidating reforms are reported to be concerned about the effects of his changes on the prospects for sound governance.Footnote 81

Afghanistan's foremost challenge to the consolidation of effective and legitimate governance comes from the continued salience of the traditional neopatrimonial equilibrium – a political order organized around subnational strongmen at the head of complex patronage networks endowed with alternative sources of authority, legitimacy, and wealth that empower them vis-à-vis the central government. Having failed in the first instance to incorporate their resources into the central government, the Karzai regime then acted to neutralize the salience of these patrimonial networks by competing with them at their own game: it attempted to build its own clientelist base in the provinces by distributing government positions to allies. Timor Sharan describes how, in return, this strategy delivered the quid pro quo of electoral support for the Karzai regime, which warned tribal leaders that if they failed to support the Kabul administration they would be excluded from local government and its attendant patronage spoils in the form of jobs, aid, and other privileges.Footnote 82

The international community's strategy of prioritizing the stabilization of the country through a combination of democratization and political deal-making appears to have acted against the peacebuilding imperative by reinforcing traditional fragmentary loci of power, many of which have now come to operate in zero-sum opposition to the central state rather than in cooperation with it.Footnote 83 Antonio Giustozzi argues that, compared with previous periods of political development in Afghanistan, political parties in the country are now intent on securing for themselves a system of electoral support in exchange for patronage distribution. Examples of such political mobilization include parties associated with the Uzbek leader Rashid Dostum and the Hazara leader Haji Mohammed Mohaqeq: in both cases, organizational development took place around the logic of securing and distributing patronage instead of along the lines of ideological or programmatic goals.Footnote 84 This system of patronage is fed, in turn, by internationally provided resources, such that the post-conflict intervention in Afghanistan can itself be said to have cemented in place a rentier-driven neopatrimonial political economy in the country.Footnote 85 William Maley goes so far as to argue that flaws with the peacebuilding enterprise, including decisions to put in place a presidential and centralized political system, have driven Afghanistan from “institutionalization in the direction of neopatrimonialism.”Footnote 86

Those dynamics – which have resulted both from the narrowness of the Bonn peace deal and from the transitional governance strategy itself – have contributed to a lack of consolidation of modern political order. The transitional governance process privileged and legitimized Karzai at the center and subnational elites in the provinces, many of whom are now enmeshed in a predatory political economy equilibrium where state structures are fragmented and captured. The drug economy and other avenues of patronage and corruption have both created pockets of stability in some parts of the country and fuelled sociopolitical breakdown and violent conflict in others.Footnote 87 As Barnett Rubin predicted, the criminalized peace economy has expanded rapidly in the country, leaving power-holders as unaccountable as they were under previous governing regimes.Footnote 88 Jonathan Goodhand notes, for example, that the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission reported that an estimated 80 per cent of parliamentary candidates in the provinces had some form of contact with drug traffickers and armed groups.Footnote 89 Poppy cultivation reached an all-time high in 2014, “stoking corruption, sustaining criminal networks, and providing significant financial support to the Taliban and other insurgent groups.”Footnote 90 Pervasive corruption, drug-related and otherwise, has undermined both state capacity and the government's legitimacy; political groups out of power, including the Taliban, use the widespread patronage and corruption to perpetuate a sense of injustice and legitimize continued fighting against the government.Footnote 91 The transitional governance process through which the international community instinctively pursued political stabilization was co-opted by domestic elites into this conflictual neopatrimonial environment. The Afghan state remains splintered, both politically and administratively – in turn making the quest for sustainable peace in the country elusive.

Neopatrimonial Political Order in Comparative Perspective

Francis Fukuyama cautioned, in his sweeping study of political order, that patrimonialism “constantly reasserts itself in the absence of strong countervailing incentives.”Footnote 92 Neopatrimonial political order has been reasserted in post-conflict Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, despite the enormous resources devoted to achieving modern political order through transformative peacebuilding interventions. The political elites in the three countries who were empowered by the transitional governance approach to peacebuilding are, unsurprisingly, as motivated to retain control over the state as they were to seize it initially. Through their control of the administrative apparatus of government, these elites have access to sanctioned streams of rent creation and distribution, which underpin, in turn, the clientelistic networks of support that keep them in power. But neopatrimonialism is a hybrid form of political order – the elements of rational-legal authority that behoove elites persist. Patron–client relationships are not coercive – they are instrumental and centered on reciprocal exchange, such that the patron uses his influence and resources to provide benefits or protection to the client, who reciprocates with political support and personal services.Footnote 93 Hence elites build and support some minimal degree of state capacity and continue to rely on the legitimacy bestowed upon them by elections, both of which are necessary to retain support from the population and international community and to continue a strategy of rent extraction.