On September 2, 2015, the Pentagon reported the visit of five People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) vessels to US territorial waters off the coast of Alaska.Footnote 1 It was the first ever incursion by Chinese navy boats into the Arctic region. Occurring only the day before China’s biggest-ever military parade, and just as US president Barack Obama was making his own first visit to Alaska to announce his new Arctic policies, PLAN’s brief voyage showcased China’s growing naval reach and desire to expand operations into Arctic waters. The five boats, consisting of three surface warships, an amphibious vessel, and a supply ship, had been participating in a military exercise with Russian forces near Vladivostok. They then voyaged thousands of kilometers north to the Bering Sea, where they transited the US Aleutian Islands, before heading home to Chinese waters.

The official US response was muted: China was simply playing the same game that the US Navy has played for years in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, exercising the right of innocent passage to show off its sea power. Behind the scenes, however, the message was clear – China was announcing that it had military interests in the Arctic and intended to expand its operations there. One month later, in late September and early October 2015, PLAN drove this point home, giving a further demonstration of emerging Arctic sea power by sending a destroyer, a frigate, and a supply ship on goodwill visits to Denmark, Finland, and Sweden.

The incursion into US territorial waters was much more than a stunning example of China’s growing maritime capacities and its ability to reach the polar regions. The frenzied international media attention over the boldness of China’s display, which drowned out Obama’s visit to the Arctic, underscored the broader import of China’s actions. The controversy associated with China’s expansion into the polar regions reflects its potential to upend the global order, just as it has done in multiple sectors of the global economy, in its nearby oceans through projection of its naval power, and even in outer space. In the past ten years, as part of its overall expanding global foreign policy, China has become a leading polar player with wide-ranging and complex interests in both the Arctic and Antarctic. China is now emerging as a member of the unique club of nations that are powerful at both poles. Polar states are global giants, strong in military, scientific, and economic terms. China’s leaders view their country’s expanding polar presence as a way to demonstrate China’s growing global power, and to achieve international recognition for this new status.Footnote 2

To anyone who was watching closely, China’s polar push has been advancing on numerous fronts, both public and private. In 2014, the Chinese polar icebreaker Xue Long helped in the dramatic rescue of the trapped Russian research vessel Akademik Shokalskiy in Antarctic waters. In 2012, Chinese entrepreneur Huang Nubo tried and failed to purchase a section of remote Iceland farmland to build a luxury hotel and eco-resort;Footnote 3 in 2014, he tried to purchase land in Svalbard, and finally succeeded in purchasing a massive tract of land in Tromsø, Norway.Footnote 4 In 2014, the China National Space Administration constructed a ground receiving station for the civil-military BeiDou-2 satellite navigation system in Antarctica, which will extend coverage to a global scale.Footnote 5 And in November 2015, China’s polar science program announced that it had attained “fully self-sufficient land, sea, and air capabilities at the poles.”Footnote 6

China’s rise as a polar power has been dramatic and rapid. When, in 2004, Chinese polar officials voiced the desire for China to overtake the level of research and involvement of developed countries active in Antarctica,Footnote 7 it seemed a far-off goal. In 2005, China’s leading polar scientist first mentioned in public the aspiration for China to become a “polar great power” (jidi qiangguo).Footnote 8 In 2013, a senior Chinese polar official stated that China was beginning the transition to achieving this status.Footnote 9 In 2013, senior Chinese polar officials publicly stated for the first time that China’s goal of becoming a polar great power was a key component of Beijing’s maritime strategy.Footnote 10

Then, in a speech given in Hobart, Australia, in November 2014, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary Xi Jinping used the term “polar great power” for the first time. Xi stated that due to “profound changes in the international system” and China’s unprecedented level of economic development over the past twenty years, China soon would be “joining the ranks of the polar great powers.” Xi told his audience, “Polar affairs have a unique role in our marine development strategy, and the process of becoming a polar power is an important component of China’s process to become maritime great power.”Footnote 11 Having China’s top leader refer to his country as a future polar great power was a signal to the entire Chinese political system that polar affairs had moved up the policy agenda. Following this speech, the polar regions were officially included in Xi’s bold new foreign policy direction, China’s “New Silk Road” (yidai yilu). In China’s bureaucratic system, the polar regions are categorized within maritime affairs. The goal of becoming a polar great power is now a key component of Beijing’s emerging maritime strategy.Footnote 12 China’s emerging status as a polar power is directly linked to its desire to seek a greater global role.Footnote 13 China’s thinking on the polar regions and global oceans demonstrates a level of ambition and forward planning that few, if any, modern industrial states can achieve. If China succeeds in its goals in the polar regions, the high seas, outer space, and cyberspace, then its quest for international status and power will be assured.

It has been difficult for China and international relations experts to grapple with China’s polar policies because the field is divided into different silos of specialists who do not have the requisite skill sets to connect the proverbial dots. Paradoxically, China’s dramatic polar rise has therefore flown under the radar – until this book. Political and strategic research on the polar regions has tended to be the preserve of a select number of Arctic-focused, and a very small group of Antarctic-focused, social scientists. Although scientists frequently integrate their research on both poles, very few social scientists talk about “polar studies” or discuss the two poles as a region. Meanwhile, the world’s most powerful polar powers, the United States and Russia, rarely use the term “polar great power” to describe their status and interests in the polar regions. Yet China is now widely using this term to sum up its aspirations and symbolize the significance of the polar regions to China’s national interests.

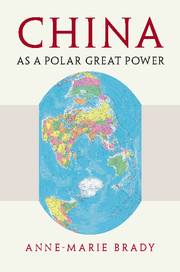

China’s focus on becoming a polar great power represents a fundamental reorientation – a completely new way of looking at the world. Nothing symbolizes this shift more than China’s vertical world map, the cover image for this book. This map, devised by Hao Xiaoguang, a brilliant geophysicist from Wuhan, has been used since 2004 by China’s State Oceanic Administration to chart voyages to the Arctic and Antarctic and, since 2006, by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as an official military map. The map was finally released to the public in 2014.Footnote 14 Hao also designed China’s new vertical national boundaries map, which for the first time included China’s controversial nine-dash-line claims in the South China Sea as part of Chinese territory, provoking a media storm of commentary.Footnote 15 Yet the international media missed the more far-reaching significance of China’s vertical world map, which was released at exactly the same time. Unlike the traditional world map, which has the Arctic and Antarctic at the edges of the world, China’s new vertical world map is dominated by a peacock-shaped Antarctic Continent and depicts the Arctic as a central ocean ringed by North America and Europe. The PLA has been using this vertical world map to help determine the location of satellites and satellite receiving stations for BeiDou-2, China’s strategic weapons navigating system,Footnote 16 in order to chart China’s new direction in the most literal sense. The map is the visual representation of China’s new global Realpolitik: pragmatic, assertive of China’s national interests, cooperative where it is possible to be cooperative, and yet ready to face up to conflict.

As the founder of modern geopolitics, H. J. Mackinder, pointed out early in the twentieth century, each era has its own geographical perspective.Footnote 17 China’s vertical map completely resets the world map to highlight the significance of the world oceans and the polar regions, creating a new geographical perspective more in keeping with modern realities. It exposes what Mackinder called the “World-Island” – the joint continent of Europe, Asia, and Africa.Footnote 18 Thus, China’s new global vision confronts the observer with how the various land masses, big continents and smaller islands, connect in one interlinked, inseparable world ringed by vast oceans. The vertical map places the rooster-shaped Chinese territory at the center of the new world order: visually dominating the Asia-Pacific, sidelining the United States, and dwarfing Europe. For centuries, geopolitical contention has centered on Europe and focused on land-based territories. And since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States has been the unchallenged global hegemon. But a new geopolitics is taking shape that reflects the unprecedented level of global interconnectedness of trade, communication, and people movement; the pressing concerns of the future, including food supplies and energy security; the consequences of climate change on geopolitics; and, ultimately, the rise of a new global power. China aims to be at the heart of this new order.

China’s declaration that it is poised to enter the ranks of the “polar great powers” reveals both a deep need for status change in the international system and an awareness of a gap in global geopolitics that China alone has the unique ability to fill. In setting its sights on the polar regions now, China is looking to the mid- to long term and planning for its future economic, political, and strategic needs.Footnote 19 The Chinese government’s stated core national interests in the current era – to maintain China’s social system and state security, to preserve state sovereignty and territorial integrity, and to ensure the continued stable development of the economy and societyFootnote 20 – all require access and engagement in the polar regions.Footnote 21 China has global interests and is well on the way to becoming a global great power. To succeed in this evolution, it must be dominant in the polar regions.

China, like other rising powers before it, seeks to improve its national security, and in doing so it inevitably will challenge the existing order. The polar regions are key sites for these new geopolitics. As Xi Jinping pointed out in his Hobart speech, the Arctic and Antarctic are ripe with economic, political, and military-strategic potential.Footnote 22 A new “Great Game” is well underway at both the Arctic and Antarctic, as various states compete for access and opportunities there.

Great powers are states that exhibit “global structural power,” or the ability to shape governance frameworks in the economic, military, and political-diplomatic sectors.Footnote 23 So how should we define polar great powers? In the polar regions, the measures – and means – of power are somewhat different. Along with more traditional forms of power and influence, in the Arctic and Antarctic a state’s investment in polar-related science is a fundamental indicator of power and intentions. Thus, to be considered a polar great power, a state must have high levels of polar scientific capacity and scientific research funding; a significant level of presence in the polar regions; and significant economic, military, political, and diplomatic capacity there; as well as a high level of international engagement in polar governance. This last factor is particularly important because, in the polar regions of the world – more perhaps than anywhere else – “structural power” comes from cooperation and participation in existing governance structures.

Going it alone in the polar regions is a strategy that only a regional hegemon, such as Russia in the Arctic, might consider taking. States that are able to dominate militarily at the two poles are truly powerful, controlling key choke points into strategic regions. Currently, only the United States, with its strong military presence in both the Arctic and the Antarctic, has this capability. Yet massive pressures on the US federal budget since the 2008 global financial crisis, which has capped spending on polar-related infrastructure and science, means that US polar capacity is steadily slipping backwards.

China’s modern strategic thought has long been greatly influenced by the ideas of late-nineteenth-century US naval strategist Alfred T. Mahan,Footnote 24 who advocated that rising powers should expand their navy, aim for global markets, and either establish colonies or else garner privileged access to resources.Footnote 25 China is following this advice to the letter. By China’s definition, the polar regions, the deep seabed, and outer space are all res nullius (literally, “no one’s property”), and hence are ripe for “colonization.” In 2015, the Chinese government announced that the polar regions, the deep seabed, and outer space are China’s “new strategic frontiers” (zhanlüe xin jiangyu),Footnote 26 strategically important areas from which China will draw the resources needed to become a global power.Footnote 27 Although this vision has only recently been made public by China’s senior leader Xi Jinping, the thinking behind it has been developing for many years.

China does not yet have a formal document outlining the government’s strategy for the polar regions, let alone formal individual strategies for the Arctic and Antarctic, but it does have a clear agenda and set of priorities and can be expected to make a formal public statement on some – but not all – aspects of its Arctic strategy during the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020). China’s polar policymakers are coy on the topic of China’s polar strategy, and in news stories aimed at foreign audiences they have publicly denied that China has one.Footnote 28 Yet in meetings for polar officials reported in specialist websites, and in classified materials, the topic of China’s current polar strategy (jidi zhanlüe / jidi guihua) and policies (jidi zhengce) are freely discussed, as are plans to formulate a more long-term, overarching, and possibly public strategy. China’s polar strategic priorities are focused on security (traditional and nontraditional), resources, and strategic science. Without a formal polar security strategy document in place, whether public or classified, China is currently acting out an undeclared foreign policy in the polar regions, and its actions provide a useful indicator of the Chinese attitude toward global governance issues more widely. In contrast to China’s opacity on its polar interests, both Russia and the United States have made formal public statements on their Arctic and Antarctic priorities and agenda in recent years, as has Norway, the only state with territorial claims at both poles, and prominent Antarctic states such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand.

China has a long-term agenda in the polar regions. Many of the opportunities in the Arctic and Antarctic that attract Chinese interest will not be available for several decades, and they will take considerable planning, coordination, and international diplomacy to maximize. The Chinese government is thus employing strategic ambiguity to defend its interests to the wider world. Hence, as two of China’s leading polar scholars point out, China works hard to “create an international image of China as a peaceful and cooperative state” in order to further China’s goals in the polar regions.Footnote 29 If international public opinion were to turn against China’s plans in the polar regions, it would harm the government’s abilities to achieve these goals. Thus, persuasion, framing, information management, and strategic communication play an extremely important role in China’s current polar strategy, and they are used to shape both domestic and global perceptions of China’s polar agenda.

Great Power Politics at the Poles

In the Cold War era, the United States and the Soviet Union dominated both the Arctic and the Antarctic. For most of the post–Cold War era, the United States has been the dominant power on the Antarctic ice, while it has treated the Arctic as somewhat of a geostrategic backwater. However, as US global power has declined, especially since 2008, a host of emergent states are beginning to take advantage of the power vacuum, and China is at the head of the pack. The Obama administration tried to rebalance to the Asia-Pacific, but became preoccupied in the Middle East and Europe. Now the Trump administration is alienating allies, accentuating perceptions of the decline of US power. The Arctic is important to the United States, as an Arctic littoral state, and yet it pays little attention to its own northern regions.Footnote 30 Relative to other foreign policy commitments, Antarctic affairs are even less of a priority for Washington. US capacities there are in a slow decline, as symbolized by the US administration’s inability to finance new icebreakers to service its bases in Antarctica and protect its interests in the Arctic.Footnote 31

Russia has more at stake in the Arctic than most countries do. It controls one-quarter of the Arctic coastline and 40 percent of the land area, and it is home to three-quarters of the Arctic’s population. Russia has been active in the Arctic region since the 1600s and receives 20 percent of its gross domestic product from Arctic economic activities such as natural resource extraction. Yet Moscow too has neglected its Arctic interests for many years. It is only now reasserting itself militarily in the region and looking for partners to open up its Arctic regions for development.Footnote 32 In the Antarctic, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia has become a weak but sometimes belligerent player, beset by aging infrastructure and limited budgets.

The Arctic is a vast sea surrounded by continents, while Antarctica is a continent surrounded by sea. Although the two poles have some physical and climactic similarities, from the point of view of governance they are vastly different. Arctic governance is in somewhat of a state of flux, whereas Antarctic governance mechanisms are considerably more settled and ordered. However, tensions are rising in both regions, and China’s emergence as a significant polar player is a contributing factor to these tensions. China’s economic power and increasing interest in garnering global influence is perceived by the more established Arctic and Antarctic states as a potential threat. Yet some also recognize China’s polar interests as an opportunity: as a chance to adjust existing balances of power, as a new source of polar scientific funding and capacity, as a source of new consumer markets, and as a deep-pocketed investor.

The Arctic has global significance as a region for a number of factors. In 2009, the US Geological Survey’s Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal study found that 22 percent of the total undiscovered oil and natural gas left on the planet is located above the Arctic Circle.Footnote 33 The Arctic region is also rich in uranium, rare earth metals, gold, diamonds, zinc, nickel, coal, graphite, palladium, and iron ore. All of these mineral resources are located on the territory of the Arctic states. The Arctic has rich fisheries and forestry, and is an important site for scientific research of global significance. Major climate change was first observed in the Arctic; the impact of climate change is much stronger there than in other parts of the world, and it has a global impact. The Arctic region is also an important site for strategic space-related research in such areas as the earth’s magnetic field and auroras.

The Arctic has also attracted intense international interest as a new shipping route. With the rapid onset of melting Arctic ice during the Northern Hemisphere summer months, many ocean-going nations are now exploring the possibility of the North and Northwest passages through Arctic seas as an alternative route between the Asia-Pacific and into northern Europe and the Americas. Though the Arctic route is hazardous and only seasonal, shipping companies are attracted to it because it can shave off a third of the time it takes to get between markets in Asia and Europe and the Americas, and it avoids chokepoints such as the Malacca Strait and conflict zones such as the Somali coast. The Arctic sea route will also be useful for the shipping of raw materials from the Arctic to industrial sectors in China, South Korea, and Japan.

The Arctic was a key site for US-Soviet military confrontation in the Cold War era, with both sides hosting significant military bases and strategic missile launch sites in the Arctic region. Virtually all of these sites were closed down or downsized in the 1990s. However, as the Arctic ice melts and tensions grow over access to Arctic resources and sea routes, many of the Arctic littoral states have been boosting their Arctic military presence. In 2013, the US government announced a 50 percent increase in the number of missiles stationed at its ground-based interceptor missile defense base in Fort Greely, Alaska. The missiles at Fort Greely are targeted at “rogue states” and the “theatre-missile threat”;Footnote 34 in other words, at North Korea, Russia, and China. In 2014, Russia announced that it planned to “militarize the Arctic,” that it was reopening a Cold War–era Arctic military base, and that its navy had begun patrolling the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic coast from the Kara Sea to the Pacific Ocean.Footnote 35 As a consequence of all these developments, Arctic geopolitics are experiencing a sea change. There is an increasingly complex Arctic security environment, while Arctic states are divided on a number of issues.

Antarctica was the site for imperialist expansion, exploration, and exploitation by leading states and their agents from the 1800s through the mid-twentieth century. Russia, the United States, Great Britain, Norway, France, Germany, and Japan were early key actors in the region, reflecting their respective power – or aspiration to power – in the global system at the time. States geographically close to Antarctica, such as Chile, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand, took a propriety interest in the territory, though they frequently lacked the capabilities of major powers to back up these interests. Then, as now, Antarctica has always been a mirror for the changing global balance of power and geopolitical rivalry. It is significant that Germany and Japan, the losers of the two major conflicts of the twentieth century, were both forced to renounce any rights to territorial claims in Antarctica as part of the terms of peace: Germany in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, and Japan in the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco.

Antarctica is widely believed to be rich in mineral resources; however, the scientific evidence of this so far is scant. Until recently, only relatively preliminary research had been done to ascertain the extent of the continent’s mineral, oil, and natural gas resources.Footnote 36 After the oil crisis of the 1970s, a number of countries engaged in exploratory mineral research in Antarctica. In a series of reports and maps published in the 1980s, a team of international researchers working with the US Geological Survey divided the Antarctic continent into three major geologic zones: the Andean metallogenic province, which is believed to contain mainly copper, platinum, gold, silver, chromium, nickel, diamonds, and other minerals; the Trans-Antarctic metallogenic province, which is speculated to be the world’s largest deposit of coal, along with copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, tin, and other minerals; and the East Antarctic iron metallogenic province, which contains significant amounts of iron ore, as well as gold, silver, copper, uranium, and molybdenum. The reports identify the key locations likely to have oil and natural gas deposits as the Ross Sea, Weddell Sea, Amundsen Sea, and the Bellingshausen Sea, with the Ross and Weddell seas likely to have commercially significant supplies.Footnote 37

China as a Polar Great Power

China’s emergence as a polar great power marks an important shift in its global presence and influence. Unlike the more established players in the polar regions, China has an increasing polar budget and program and plans for political, economic, scientific, and military expansion into the polar regions. China’s expanding polar program demonstrates the resources that Beijing now has at hand to project power globally. Current analysis of China’s growing power is essentially concerned with the question: As China becomes more powerful, will it attempt to change the existing global order? Power depends on the ability to influence others and achieve one’s own goals. This book analyzes China’s polar strategy, currently in the stage of doctrine formation and implementation, as a framework for understanding China’s global ambitions, its ability to achieve them, and its attitude toward existing norms and governance structures. It also examines the extent to which existing polar regimes will be able to cope with the changing balance of power and other new pressures.

Many observers speculate that China’s increased Arctic and Antarctic activities may challenge the interests of other states active in the Arctic and Antarctica. In recent years, there has been a flurry of policy papers and academic papers in English published on China and the Arctic.Footnote 38 In contrast, much less scholarly writing in English has been done on China and the Antarctic.Footnote 39 Yet China, like all the leading states in the global system, does not focus on one of the polar regions to the exclusion of the other. There is, as yet, no scholarly study in Chinese, English, or other languages of the range of China’s polar interests and current government policy, their possible effects on other polar players, and their potential position in China’s growing global role. Thus, China as a Polar Great Power breaks new ground to provide a detailed, in-depth study of China’s long-standing polar interests and their implications for global governance. It is also the first study to examine China’s overall polar activities and policies and locate them where they properly belong, within China’s evolving maritime strategy (haiyang zhengce). It will discuss the part that China’s polar initiatives play in other key concerns of the Chinese government, such as planning for China’s long-term energy needs, maintaining its economic development, developing a strategic space program, and boosting the Chinese government’s national and international prestige.

China as a Polar Great Power aims to help fill a gap in our understanding of China and its international relations and the challenges faced by current polar regimes. It explores a series of questions, including the following: What are China’s strategic interests in the polar regions? Will China’s rise in Antarctica impinge on the interests of other Antarctic Treaty nations, or of those that have not yet joined the treaty but have expressed an interest in the affairs of the Antarctic continent? Will China demand an upheaval of the Arctic Council to allow itself more of a voice in Arctic governance? Will China demand the establishment of a new Arctic body? Does China support the continuance of the Antarctic Treaty and its 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection? What are China’s views on polar governance more broadly? Who are the actors in China’s polar decision-making? What are China’s polar strengths and weaknesses? What position does China take on key policy issues in the polar regions such as sovereignty and the exploitation of resources? Will China’s growing interest in the Arctic impinge on the interests of the Arctic littoral states? And will China’s perspective on polar issues appeal more widely to other states, helping to shape new global norms?

This book places China’s polar involvement within the context of its evolving domestic and foreign policy, over eight chapters of analysis and discussion. Chapter 1 outlines the governance systems that manage the Arctic and Antarctic, and the range of rights that China and other states can access in these regions. Chapter 2 shows how China uses different framing techniques (including coded language and audience-specific messaging) to influence foreign and domestic public opinion on the polar regions, and examines the place of the polar regions in China’s national narrative. Chapter 3 discusses the three strategic drivers of China’s activities in the polar region – security, resources, and science – and chapter 4 discusses the CCP-state-military-market nexus in China’s polar policymaking. Chapter 5 evaluates China’s polar power from the point of view of polar presence, logistics capacity, budgets, scientific achievements, and polar leadership. Chapter 6 discusses China’s position on contentious issues in polar governance such as Arctic and Antarctic sovereignty, access to resources, and environmental protection. Chapter 7 analyzes what China’s polar engagement tells us about Beijing’s attitude toward global governance, and the extent to which China can now be considered a global great power. Finally, chapter 8 concludes and summarizes the findings.

China as a Polar Great Power draws on a combination of Chinese-language primary source materials, classified policy papers, discussion documents, and interviews. In addition, careful use has been made of open-source writing by Chinese scholars and policymakers on polar affairs, supported by interviews, primary documents, and secondary source materials in English and other languages. In many polar states, nongovernmental organizations, business interests, and public intellectuals play a major role in polar politics and policymaking. Currently, in China their influence is much more curtailed, but as this book will show, these external actors are already helping to shape some aspects of polar policymaking in China and may become more prominent in further aspects as time goes by. Every effort has been made to accurately reflect internal Chinese policy discussion on polar issues in this book. Because of the political sensitivity of this research, all Chinese interview sources have been protected with anonymity. Throughout the book, the realist (in international relations theory terms) perspectives of the Chinese-language sources are presented as an accurate reflection of official opinion on the polar regions. The level of forward planning within the Chinese bureaucratic system is a symptom of this realist theoretical mindset, which has an underlying assumption of states as the most important actors in the global system, competition for resources as a key driver of global politics, and the international order as a hierarchy of states.

My research into China’s polar interests was inspired by senior colleagues at the research center Gateway Antarctica in the University of Canterbury, who in 2006 asked me to investigate the topic of China and Antarctica because, as they told me, “China is spending a lot of money there, and we don’t know why.” The answer to that question has taken me in directions neither they nor I ever could have predicted. Researching this book has been like putting together a giant jigsaw puzzle, requiring a massive amount of academic detective work. In the following pages, I lay out the various pieces of this puzzle – China’s polar interests, its polar capacity, and its polar policymaking process – and show how the pieces fit in to China’s current global economic, political, and military expansion.

China’s push into the polar regions encompasses maritime and nuclear security, the frontlines of climate change research, and the possibility of a resources bonanza. China’s growing strength at the poles will be a game changer for a number of strategic vulnerabilities that could shift the global balance of power. The Chinese navy is not far off from developing a credible sea-based deterrent, and access to the polar regions is crucial to this endeavo – as is China’s strategic space science which will enhance the PLA’s C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) and cyberwarfare capacities. In the past ten years, China has spent a lot of money at the poles – investing more in capacity than any other nation – because access to all the opportunities available in the Arctic and Antarctic are essential for China to achieve its goal of restoring its international status and becoming “a rich country with a strong army” (fu guo qiang bing). Both the Arctic and Antarctic have unresolved sovereignty issues, so China has acted like any great power would, dramatically extending its presence there and responding to any initiatives to restrict access to the poles with great resistance. A new international order is emerging, and the polar regions offer front row seats to observe this changing geopolitics.