64 results

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 196-217

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Drama in Public

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 160-188

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index locorum

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 218-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Out of the Shadows

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 14-33

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note to the Reader

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Politics and Propaganda

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 80-106

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

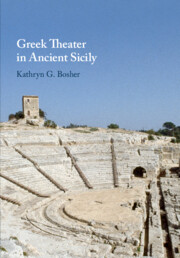

Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

-

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021

General Index

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 221-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Taking Theater Home

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 107-159

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Cult and Circumstance

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 34-79

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Foreword

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 1-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2021, pp 189-195

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - ‘Romantic Poet-Sage of History’

-

-

- Book:

- Herodotus in the Long Nineteenth Century

- Published online:

- 13 March 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 March 2020, pp 46-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Ancient Theatre and Performance Culture Around the Black Sea

- Published online:

- 12 November 2019

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2019, pp 490-541

-

- Chapter

- Export citation