78 results

Understanding Iago, An Italian Film Adaptation Of Othello: Clientelism, Corruption, Politics

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare Survey 75

- Published online:

- 24 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 08 September 2022, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Shakespearean Cinemas/Global Directions

- from Part I - Adaptation and Its Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen

- Published online:

- 11 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 52-64

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Three - Hamlet and the Moment of Brazilian Cinema

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 92-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Two - Thematizing Place: Hamlet, Cinema and Africa

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 59-91

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter One - Hamlet, Cinema and the Histories of Western Europe

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 23-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 284-292

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Six - Gendering Borders: Hamlet and the Cinemas of Turkey and Iran

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 188-218

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A note on texts and titles

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp xv-xv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 1-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 256-283

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp viii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp x-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Five - Hamlet and Indian Cinemas: Regional Paradigms

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 153-187

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Filmography

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 252-255

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Four - Pairing the Cinematic Prince: Hamlet, China and Japan

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 121-152

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Seven - Materializing Hamlet in the Cinemas of Russia, Central and Eastern Europe

-

- Book:

- 'Hamlet' and World Cinema

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019, pp 219-251

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

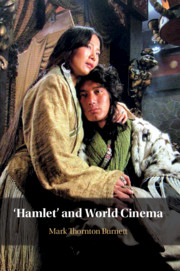

'Hamlet' and World Cinema

-

- Published online:

- 21 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2019