36 results

Chapter 17 - Flute Theatre, Shakespeare and Autism

- from Part V - Reimagining Performance

-

-

- Book:

- Reimagining Shakespeare Education

- Published online:

- 02 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 February 2023, pp 271-280

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

About Shakespeare

- Bodies, Spaces and Texts

-

- Published online:

- 09 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 01 October 2020

-

- Element

- Export citation

271 - Film and Film Audiences

- from Part XXVIII - Shakespeare and Media History

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1935-1940

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Connecting the Globe: Actors, Audience and Entrainment

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare Survey

- Published online:

- 05 November 2015

- Print publication:

- 24 September 2015, pp 294-305

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Shakespeare and the London stage

- from Part III - Shakespeare on the stage

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century

- Published online:

- 05 August 2012

- Print publication:

- 19 April 2012, pp 161-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contributors

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century

- Published online:

- 05 August 2012

- Print publication:

- 19 April 2012, pp ix-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Falstaff's Belly: Pathos, Prosthetics and Performance

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare Survey

- Published online:

- 28 November 2010

- Print publication:

- 14 October 2010, pp 63-77

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Behind the scenes

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare Survey

- Published online:

- 28 November 2009

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2009, pp 236-248

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

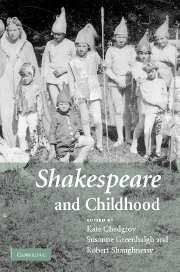

PART 1 - SHAKESPEARE'S CHILDREN

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp 13-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Shakespeare and Childhood

-

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007

1 - Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp 1-12

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp 277-284

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

APPENDICES

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp -

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note on the text

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on contributors

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

PART 2 - CHILDREN'S SHAKESPEARES

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare and Childhood

- Published online:

- 22 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 September 2007, pp 115-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Nazi Appropriation of Shakespeare: Cultural Politics in the Third Reich. By Rodney Symington. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2005. Pp. ix + 310. £74.95; $119.95 Hb.

-

- Journal:

- Theatre Research International / Volume 32 / Issue 2 / July 2007

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 July 2007, pp. 216-217

- Print publication:

- July 2007

-

- Article

- Export citation