English Poetry Night

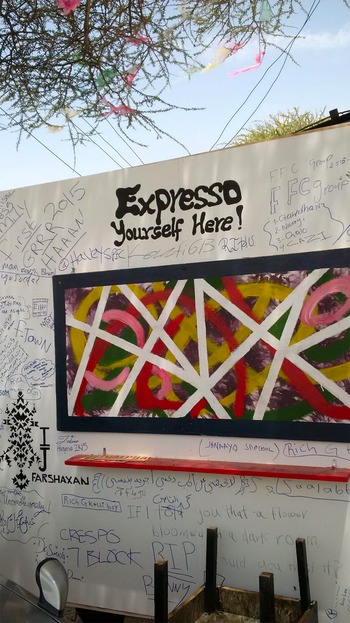

We were at Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse for a poetry night in the summer of 2015 when the discussion about authentic and inauthentic Somaliness arose. Inspired by the creativity of its founders, Sarah Haji and Kamal Haji, this café had initiated several artistic/cultural projects as a way to keep its patrons entertained as they enjoyed their coffees. There were several opportunities for creative and didactic amusement, among them a huge whiteboard planted outside the café for purposes of self-expression. On this board was written “Expresso Yourself Here!” (See Figure 2, below). This phrase, “Expresso Yourself,” common in coffeehouses, is a witty wordplay on a type of coffee called espresso; this pun is interpreted as a call for anyone to “express themselves” as they enjoyed coffee. In the context of Cup of Art, however, it had acquired a new meaning: A black ink marker rested permanently at the deck of the board, and anyone could use it to write or draw anything they wanted on the board—from simply writing their names and phone numbers in self-aggrandizement to illustrations of themselves, incomprehensible graffiti, or their dreams for Hargeisa. There was no restriction or guidance on what one might imprint on the board. It signalled either a longing for freedom of speech and expression or a celebration of creativity, identity, and belonging [see Figure 2 below]. Like that board, the coffeehouse offered other avenues for creative expression in events such as English poetry night, fashion nights (especially for female patrons), and quiz night. Responding to public demand, the café later diversified its poetry platform, adding Arabic Poetry Night and Somali Poetry Night.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Above: A poet reads before an audience at Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse, August 2015. Photo courtesy of the author

Figure 2. Left: The White Board: Expresso Yourself Here! August 2015. Photo courtesy of the author

The fashion and poetry nights were the most popular events, with a clientele composed mostly of diaspora returnees from the UK and North America. Other patrons included “high-end” Hargeisans and expatriate employees of international NGOs. These events were enabled by the ways in which the café packaged itself in an overtly “cosmopolitan fashion” compared to other coffeehouses and eateries, and which would ultimately be the source of its troubles and contestations.

The tradition of the poetry nights was that after the reading, the audience had the opportunity to interact with the poet by way of questions or comments. Questions would come from the audience in any of the three main languages—Arabic, English, and Af-Soomaali—as the questioner felt proficient. One night during an English poetry session, a female poet who expressed herself in English and Arabic had to respond to several questions coming her way in the Somali language. It was quite provocative, as it is common for homebred Somalis to mock their diaspora-returnee kindred as lacking in linguistic proficiency and needing reorientation in the culture, what is locally termed as dhaqan celis (see also Mahdi & Pirkkalainen Reference Mahdi and Pirkkalainen2011). One of the questioners, speaking in Af-Soomaali despite having a good knowledge of both Arabic and English, asked whether the poet considered herself Somali, although she claimed to express herself better in Arabic. In response, in not fluent Somali (judged by the audience), the poet said:

“I am Somali; I was born in Yemen, and have grown up in Egypt. I speak Somali but Arabic comes more easily to me than Somali.”

“Are you then Somali or Arab?” the questioner pressed on.

After a slight pause, the poet challenged rhetorically, still in Af-Soomaali, “I am Somali. Both my parents are Somalis. My clan is here. What else would I be!”

Shaking his head in disapproval, the questioner turned to his friend, and quipped in English, loud enough for all to hear: “These Somalis are not Somalis!” and the entire house responded with hearty laughter.

Besides the hilariousness of the questioner’s quip, it was packed with meaning and multiple subjectivities, which I want to address in this article. First, in using the plural “these Somalis” and not the singular “this Somali,” the questioner was not referring to the single poet in front of him but rather a section of Somalis who shared the poet’s story of being born and raised in other countries and possessing “cultural deficiencies” that manifested in different forms such as language. Second, the questioner simultaneously offered approval and disapproval of the poet’s Somaliness, which actually speaks to an enduring dilemma; while he agreed that the poet was Somali by parentage, he rejected her Somali identity because she lacked something, namely, Somali language proficiency. Here, we are given a glimpse into, and made to appreciate, the multiple layers of Somaliness and the ingredients that make a complete or thoroughly authentic Somali. With that single statement, the gathering was led into a discussion, which is at the core of Somaliland’s new imaginary as an independent country from Somalia: the question of identity and belonging.Footnote 2 On the one hand, this discussion relates to the centrality of language in cultural expression, with language being a carrier of history and culture, questioning how one can identify with one cultural community but speak a different language. On the other hand, the discussion speaks to Somaliland/Somalia’s blighted history, which ended in civil war. The protracted condition of insecurity has forced the dispersal of many Somalis across the globe, and their return reveals them as dislocated from their homeland. Also, this discussion relates to Somaliland’s relationship with the world and other traditions: Is Hargeisa willing to embrace identities and modernities that are deemed to be steeped in foreign traditions—even when they are carried by people with Somali blood—in a world that has become more connected through capitalism and our opposition to it (Ahmad Reference Ahmad1992) or as conscripts of a colonial modernity (Scott Reference Scott2004)?

The picture that emerges from the incident at the poetry night event is that while all self-identifying Somalis were in fact Somali, some were more Somali than others, and some may not be Somali at all, despite retaining the lowest common denominator of Somaliness: blood and parentage. This article pulls these different strands into the conversation on identity in late postcolonial Africa, that is, after the collapse of the dreams (such as development, freedom, peace, and democracy) that animated the anticolonial struggle. This discussion is certainly not new. Several theorists and scholars, including Aimée Césaire (Reference Césaire1972) and the entire Négritude movement, Frantz Fanon (Reference Fanon1961), Partha Chatterjee (Reference Chatterjee1986), Lidwien Kapteijns (Reference Kapteijns2009), David Scott (Reference Scott2004), and others have previously dealt with questions of national identity in the postcolonial context. However, in the immediate postcolonial moment, roughly between 1950 and the 1980s, responses to these questions seemed directly addressed to an outside-driven colonial force that the African postcolonial intelligentsia had the power to resist, while building its own “authentic” identity. This meant a longing for “complete decolonization” (see, for example, Ahmed Reference Ahmed1995; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996; Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns2009). The intelligentsia (scholars and activists) of this time quickly found themselves in a dilemma, which Chatterjee (Reference Chatterjee1986) termed the “liberal-rationalist dilemma.” This dilemma was marked by the challenge to be traditional but modern at the same time (Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns2009). Reflecting on this dilemma, Chatterjee writes that nationalist thought in that moment (with regard to identity and nation-building) was

…both imitative and hostile to the models it imitates… It is imitative in that it accepts the value standards set by the alien culture. But it also involves a rejection: in fact, two rejections, both of them ambivalent: rejection of the alien intruder and a dominator who is nevertheless to be imitated and surpassed by his own standards, and rejection of ancestral ways which are seen as obstacles to progress and yet also cherished as marks of identity. (Reference Chatterjee1986:30)

The problem was that while new nation-states wanted to escape a colonial modernity, they had to build on the institutions that colonialism had left behind. These institutions were not only discursive but also of a political and administrative nature. The critique of the present—that is, after the postcolonial state “failed” with civil wars and massive underdevelopment, as has been the case in Somalia leading up to 1991 and onward—is that the actors of that time failed to completely and fully decolonize and do away with any trappings of colonial modernity. There was a time when it was actually fashionable to blame all of Africa’s problem on the “unending legacy of colonialism.”Footnote 3

David Scott has persuasively challenged this view, noting that even the intelligentsia of that time, besides having agency, never set out to make this mistake, of longing for “total revolution.” It was not even a dilemma they faced in the Chatterjeean sense of offering them choices, but rather a process of conscription. According to Scott (Reference Scott2004), they were conscripts to a colonial modernity, not volunteers to it. They could not choose to be traditional or modern; they had to exercise their agency in the “problem space” that postcolonialism offered them. As may be seen in the case of Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse, questions of “authentic identities” display a blindness to the problem space in which individuals exercise their agency. Former refugees who return from the diaspora to Somaliland did not choose to adopt a Western colonial modernity and sensibility, but their refugee status conditioned them to this specific modernity as they received sanctuary in Europe and North America, which also ended up re-ordering their cultural and political worldviews. Incidentally, and perhaps unfortunately, the actively mobilized Somaliland public identity assumes that the embrace—partial or complete—of Western modernities (such as cultural norms relating to family, language, community values, and cuisine) partly explains the inefficiencies and tribulations of postcolonial regimes (Somalia), and thus keeping some values authentic and uncorrupted is not simply essential moving forward but also contains socio-political safeguards. What is true here is that the Somalilanders, in imagining a new future which is bereft of modern/Western or colonialist corruptions are reading from a familiar playbook, one that explains Africa’s problems as the legacy of colonialism. Writing in 1996, Mahmood Mamdani argued that all attempts at writing a script for an African legal renaissance, for example,

…shared a common dilemma, for all tried to overcome the colonial legacy formally rather than substantively. Whether customary rules were simply restated in writing or were also codified through unification or whether they were integrated into a single body of law, the distinction between the customary and the modern remained. (Reference Mamdani1996:131–32)

With this distinction being etched permanently, Mamdani proposed that effective opposition against this unending legacy, and thus reforming the African continent, would mean effectively linking the rural to the urban (1996:297), creating a singular sensibility about governance—say, governed by a common law. Thus, Mamdani argued that the failure to make these linkages possible, which meant sustaining the bifurcating legacy of colonialism, explains the several challenges of the postcolonial African state. But criticizing the postcolonial intelligentsia for failing to “substantively” end the legacies of colonialism is to be blind to the impress of history. It is to assume that they were “volunteers” to a colonial modernity, and not its “conscripts” (Scott Reference Scott2004:135). This article does not seek to question the claim of longing for total revolution, but rather to focus attention on the conceptual-theoretical challenges and conditioning limits of such framing.

The questions that defined the incident at Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse on that poetry night were the same questions that the venue had had to deal with since its opening: How authentic and truly Hargeisan was a café located in Hargeisa but named “Cup of Art,” and “Italian,” in a context where Somaliland is seceding from and demanding international recognition from Italian-colonized Somalia? In this context, the reference to “Italian” mobilizes and makes legitimate the problematic marriage that British Somaliland had with Italian Somalia in June 1960. How traditionally Somali was “Cup of Art” in an “organic,” Islamic, and traditionally self-identifying city? This Somaliland coffeehouse, owned by a Somaliland-born diaspora returnee investor, appeared to ignore not only the present cultural sensibilities of being Somali in Somaliland but also the political aspirations of the Somaliland state––secession from Somalia––making it not only “un-Somali” but also politically “anti-Somaliland.”

To discuss the above problematic and other related matters, this article, which is about unpacking the imagery of Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse in Hargeisa and its rebel life and legacy, will begin by visually painting this rebel café and then ethnographically describing what I term as “organic” Hargeisa. The idea is to show how the two often collided over questions of identity and belonging—and authenticity and inauthenticity. Building on theoretical debates in the scholarship on authenticity and civilization/traditions being narrative of contact (Mursić Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013; Asad Reference Asad2009), and publics and counterpublics (Warner Reference Warner2002), the article draws conclusions about the theoretical foundations of the politics of identity in Hargeisa in a post-civil war and secessionist context, and discusses broader debates on the contest between authentic African traditions and Western modernities, pointing to the dilemma and problems of seeking “authenticity” as response to the failings of the postcolonial state.

As a Ugandan academic, I first travelled to Somalia/Somaliland in 2012 and visited the country for at least a month every year thereafter. Fieldwork for this article took place mostly in 2015 in the course of my substantive PhD fieldwork, which lasted eight months. As a scholar in cultural studies, popular culture, and anthropology, the café spoke to me directly, especially since I was often involved in organizing the event nights. On normal days, I spent extended hours in this space, sometimes simply hanging out—as anthropologists tend to do––and sometimes conducting my interviews here, or oftentimes writing.

The Rebel Coffeehouse

After close to two years of service, in August 2016, Cup of Art closed its doors to its customers. The reasons for its closure are mostly outside the cultural-identity debate that informs this article. But this coffeehouse embodied the identity question in Hargeisa in its contemporary time. Hargeisa continues to craft itself into (ironically) the cosmopolitan capital of Somaliland, open to traditions from elsewhere, and especially more moderate in its Islamic hue than its neighbor Somalia to the south, which has been branded extremist in most media discourses. Against the background of the civil war and a quest for international recognition as an independent nation-state, questions of identity, with tradition on the one hand and Western/colonial modernity on the other, have been a major bone of internal contestations. Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse was one of those many spaces that embodied this push and pull in a more radical way. The contest played out in ways that involved mild moments of violence, with attempts by the police to close it down for its cultural inappropriateness. (Other spaces of smouldering controversy include Hiddo Dhawr Tourism Village, Xarunta Dhaqanka e Hargeisa [the Hargeisa Cultural Centre], especially during the 2015 Hargeisa International Book Fair, and the National Theatre).

Located in the Shacab area, about three hundred meters from the presidential palace, this café enjoyed a location at the intersection between the “two Hargeisas,” if a class differentiation were loosely forced onto this small town. The eastern side of Hargeisa is wealthier, swankier, and more organized than the western side, which is considered “downtown.” Like the presidential palace, Cup of Art sat somewhere in the middle. Hargeisa’s main highway, along which this coffeehouse was located, is part of the road from Berbera Port on the western side of the Red Sea, running through Hargeisa to Gebiley on the Eastern side and then to Wajale on the border with Ethiopia. This road also intersects with another feeder road running from Egal International Airport, which most international visitors to the country use on their way to Hargeisa’s most popular and biggest hotel, Maan Soor Hotel. From downtown, after Shacab, one travels through the posh neighborhoods of Jig-jiga yar, Badacas, and Boqol iyo Konton.Footnote 4 For most of its active life, the café lay in this area, but it later moved off the main highway, and would close shop a few months thereafter. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3. Night lights at Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse, located in the Shacab area. Photo courtesy of the author

Figure 4. Inside an empty Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse: Sarah Haji and her staff at work. Photo courtesy of the author. Note the writing on the wall at right: “Great coffee is a pleasure, Great Friends are a treasure”

Opening in March 2015, Cup of Art was a conspicuously “multicultural” hangout in Hargeisa among those that never closed until late in the night. There were other eateries and teashops in town, which exhibited characteristics similar to Cup of Art. These included Summertime, 4 Seasons, Fish and Steak (which used to be called Obamas), and Royal Lounge. All these are located on the same side of the capital––the wealthier side. Their English names exposed an affiliation with European and North American landmarks and features, and this set them apart from the other food and coffee joints as they depicted a fondness for the outside world. Other eateries and teashops around town were often named after individuals, using the distinctively “Somali” names, or had names of villages or words in Somali or Arabic, such as the Guleid Hotel, Damal Hotel, Hanah Restaurant, Saba Restaurant, or Lalys Restaurant, among others. Other names were Somali vocabularies such as Maan Soor, which literally means “satiated.” As my ethnographic description of Cup of Art will reveal, neither of the other coffeehouses in its category was as revolutionary or as rebellious. This particular café exhibited a peculiar uniqueness unseen before in Hargeisa.

I will discuss three distinct but related features and performative practices that defined Cup of Art as a rebel coffeehouse in Hargeisa. The first was its name and outward appearance. As discussed above, its sub-name—Italian Coffeehouse (in British-colonized Somaliland)—was rebellious enough, as it referenced the difficult history of the country, especially with the nemesis being Italian-colonized Somalia in the south. As one random client would comment to me, “this Italian thing should have been opened in Mogadishu,” registering disapproval of the name. The second is a series of practices with overt appeal toward Englishness and elitism: On its four walls, the coffeehouse was adorned with paintings, poems (in English), quotes, and slogans depicting cultural and literary traditions from different places around the world. These included quotes ranging from celebrations of the sweetness of coffee and love to quotes from the novels of Sherlock Holmes and Alexander Pope’s poetry. There were impressions of the British and Swedish flags, and an abstract painting of Turkish whirling dervishes.Footnote 5 (In the line of flags, the national flag of Somaliland was conspicuously missing, and it only came later on the insistence of the proprietors’ parents after they received several complaints from elderly patrons).Footnote 6 One could not miss a modest collection of notable romantic English fictions piled on a shelf for any interested reader to investigate. With most of the writings on the walls in English, and a menu serving a wide variety of teas and coffees “brewed to the perfection of European and regional tastes,”Footnote 7 Cup of Art was conspicuously exotic.

The third example of rebellious behavior included the inversion of closely observed café traditions in Hargeisa: Cup of Art made a practice of playing background music (Western pop and band music) for its patrons the entire time its doors were open. Music is strictly forbidden in open places in Hargeisa. Indeed, for playing soft music in its background, the café owners often received vigilante elders asking them to desist from the practice, suggesting that they perhaps should play audios of recitation of the Holy Quran instead. Cup of Art management rebelliously, almost stubbornly, never changed their policy about music but instead played more and even louder.

The café’s main waitress was the owner, Sara Haji, who as a woman was not allowed to attend to customers. But Sara Haji often attended to her customers and was the major marketing face of the café. This represented a major inversion, since in Hargeisa, females, despite being free to own cafes and restaurants, are expected not to wait on customers—something understood as “Islamic tradition.” Thus, male servants are often hired for this function, although females are free to do other jobs such as cleaning. For attending to her customers (having worked as a barista and waitress in London for years, and in hotel management in Muscat, Oman), Sara Haji was often accused of “embarrassing her clan.” She was plenty of times called a “whore,” in relation to her freely mingling with men as she served them at her coffeehouse.

This condition was not helped by the fact that Cup of Art would often stage music shows for the group Black East Band, whose music was overtly “un-Somali,” so to speak. Although music is generally abhorred in Somaliland for religious sensibilities, a certain genre of music is openly respected and listened to. This is often called the Heeso, or simply traditional music with modern instruments and beats.Footnote 8 However, no music can be played in public except in specific moments such as national celebrations, weddings, and on television. On a few occasions, shows were staged at the Crown Hotel and other places, including Hiddo Dhawr Tourism village. Because of this, these places—Crown Hotel and Hiddo Dhawr—are viewed with subtle disdain by certain sections of the community. Indeed, the proprietor of Hiddo Dhawr, Sahra Halgan, had to resign from her political party, as her business was being used to discredit her party for having a member involved in promoting “moral corruption.” All this is despite the popularity of music composition and production, and Hargeisa being heralded as the music and arts capital of the Somalis.Footnote 9

Against such a background, Black East Band, whose music was a combination of rap, American R&B, and Nigerian pop music beats, often in English, performed at Cup of Art, inside and outside the café’s compound. Indeed, in August 2015, Cup of Art was shut down for two days, for holding a Black East Band event. In the aftermath of this August closure, the café’s proprietor went to the nearby police station to demand its re-opening, and she was told that “many cases” of “indecent” behavior (especially including playing music, and the “un-Islamic” conduct/fashion of its revellers) had been reported to the police station, although the police had been reluctant to follow up on these complaints. To put this narrative in proper context, we need to turn to the city of Hargeisa, its public organization, and its imagined public identity.

Organic Hargeisa

To understand why Cup of Art might be considered rebellious or nonconformist, one has to appreciate what, after Michael Warner (Reference Warner2002), I have called the Hargeisa “public identity predefined.” Writing about predefined publics as opposed to ordinary publics that are supposed to be self-organizing/self-mobilizing, the American literary critic Warner compares a “predefined public” to a bureaucracy or an administration-organized public, such as where one goes to apply for a driver’s license or membership in a professional organization, and the bureaucracy or administration would have set the criteria for belonging. The rules are pre-set, and (new) members are expected to conform without deviation. Such publics are totalitarian in nature, Warner warns: “Such is the image of totalitarianism: non-kin society organised by bureaucracy and law. Everyone’s position, function and capacity for action are prescribed for her by the administration” (Reference Warner2002:69).

Under a predefined public, individual agency and creativity are conditioned to the bureaucracy and administration. Every member who belongs to this public must operate from within the prescribed boundaries. Warner notes that in such a situation, the individual is rendered powerless, as any attempts at deviation are heavily censured. This is not simply about the punishment of deviation, but rather about the authority of institutional and discursive practices that sustain this predefined public. The community thus effaces individual agency by predetermining their sensibilities and identity aspirations, and it also makes sure there is absolute conformity through a series of practices, sometimes reinforced by the use of violence. I use Warner’s theorization of the two types of publics, one that mobilizes itself (such as the ways in which texts mobilize their own reading publics), and the other that is predefined through bureaucracy and administration to contextualize Hargeisa’s imagined public identity—which I find to be predefined. I have called this “organic Hargeisa,” picking the term from the German-American political scientist William Safran.

My reading of Hargeisa as an “organically” organized community builds on Safran’s reading of the German society that fostered the “myth of return” into its diaspora communities: the idea that “Germany is not a country of immigrants” (Reference Safran1991:86). Safran noted that German society was traditionally defined ‘“organically” rather than “functionally,” with “citizenship that often tended to be based on descent rather than birth (or long residence)” (Reference Safran1991:86). It was the fear not just of inundation by foreigners, but also of cultural contamination, say through Islamization, which undergirded this sense of identity and belonging (Reference Safran1991:86). The German elite and policymakers, in different ways, often reminded “newcomers” that they would eventually have to go back to their original homelands. My appropriation of the term is not to underscore the idea that Somaliland may not allow citizenship to “foreigners” who have stayed long or those “foreigners” born in the country. Instead, I use it to emphasize the notion that in the cultural-social domain, there is an aspiration for a “descent,” “organic,” or autochthonous form of cultural/public behavior in Hargeisa, something organically contained—and opposed to contamination. As German society would despise Islamization, Hargeisa despises any display of “Westernization,” meaning practices that are often problematically classified as un-Somali or un-Islamic (Abdile & Pirkkalainen Reference Mahdi and Pirkkalainen2011). In the process, the conclusion is that certain cultures and practices are not welcome and should remain where they were born. This can mean that Somaliland is not a home for foreign cultures, which suggests that Hargeisa’s public and sense of belonging are, to return to Michael Warner’s terms, not self-organized but pre-organized/predefined. Part of my contention here is that in Hargeisa, certain practices have become inherently foreignized, and are openly chastised—both discursively and institutionally. But how did it all start?

Following the rehabilitation and declaration of Somaliland statehood in 1991, a new national identity continues to be imagined that seeks to separate Somaliland from Somalia. During the 1960 unification between British-colonized Somaliland and Italian-colonized Somalia, cultural homogeneity—language and religion—were adduced as central grounds for the union. Hargeisa, as the financial and political capital of this new secessionist country, has also remained the main center for cultural and political production.Footnote 10 An identity has to be crafted and mobilized in Hargeisa for the new country of Somaliland. It is evident that Somaliland has sought to define itself as a Muslim city with binding Islamic principles and symbolism. This journey perhaps started in 1981–82 during the war against Siad Barre, when the Saudi-based wing of exiles that identified as Islamist and separatist headed the Somali National Movement (SNM), the rebel group that later became the secessionist champions in Somaliland (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2008:64, 175). When the Saudi-based wing was in charge of the SNM under the leadership of Sheikh Yuusuf Ali, “SNM committed itself to Shari’a law and to instruct its fighters, who were renamed mujahedeen (holy warriors), in Islamic teachings and practices” (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2008:64). This influence continued even after the troops moved to Ethiopia and the leadership of the London-based faction had returned. Indeed, years later, Hargeisa, headed by SNM cadres, continues to nurture a correspondingly stricter Islamic symbolism for this identity. On many occasions in Hargeisa, a discussion of Somali culture encompasses a fusion of Islam and select elements of tradition. Despite the difficulties in resisting external influences, ethnography in Hargeisa suggests that Islam in Somaliland is a strictly guarded and revered public commodity.

From the symbolism of the national flag, which has the first pillar of Islam—there is no God but Allah, and Muhammad (PBUH) is His Messenger—at its center, Somaliland has several other representative features that suggest Islam as a core ingredient of its national-cultural imaginary. Several examples in popular culture stand out: The Islamic calendar operates alongside the Gregorian calendar, with Thursday and Friday being the weekend days, not Saturday and Sunday as in the rest of East Africa. The beginning of the New Year in the Islamic calendar—the day of Muharram—is a public holiday. Dress codes, especially for women, are strictly enforced. The wearing of all-covering capacious dresses and veiling for women as a symbol of Islamic modesty is strictly observed. Airport security requires female visitors to Somaliland to be dressed in capacious garments with (sometimes symbolic) head covering. The same is expected of all females living in the country, especially when they are entering the public domain. A simple head covering leaving the ears and neck region uncovered—which is common with diaspora returnee females—is also viewed with contempt.

In popular advertisements on billboards and artistic paintings on walls, women are depicted wearing proper Islamic covering. For the males, on the other hand, sporting a pair of beach shorts and T-shirt is also contemptuously looked upon as un-Somali, if not outright foreign, as reinforced in the short film by Amazing Technology Group (ATG).Footnote 11 It is important to note some difference with regard to fashion between gender divides. Fashion enforcement standards for men are not as stringent as they are for women, with females being officially policed at airports and roadblocks, and by vigilantes and other elders in market squares and restaurants.Footnote 12

Premarital sexual encounters, and indeed any potentially extramarital affairs, are forbidden in the Islamic tradition. In Hargeisa, efforts are made to enforce this religious requirement. At the reception desks of several hotels, and sometimes inside the hotel rooms, there are notices hung on the walls asking clients to show proof of marriage—that is, with a marriage certificate—if they are to have visitors of the opposite gender in their rooms. With relation to prayer, for example, it is a cultural observance for all shops and restaurants to close their doors as soon as the call to prayer is made. Even if those inside may not dash out for prayer, in the spirit of respect for prayer time, shop doors close and are opened again only after prayer is finished. This position is cemented by the annual growth in the number of mosques in the city. In 2010, Hargeisa had a total of 500 mosques; by 2011, the number had grown to 550.Footnote 13 We can note here that Hargeisa aspires to a sort of closed, pure, and pristine identity, which is mostly predefined through stricter notions of Islam and traditions such as the Heer, the moral commonwealth which ensures unity of all Somalis in their different clans.Footnote 14

Among other things, Islam is referenced as one of the most important ingredients for peace and unity in Somaliland (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2008; Jhazbhay Reference Jhazbhay2008; Renders Reference Renders2007)—peace and unity which have eluded its hostile neighbor, Somalia. Islam is a major ingredient in Somaliland’s idea of collective identity, as immortalized in the national flag (Bradbury Reference Bradbury2008); it is credited for taming clannism, the mechanism through which internecine conflicts have tended to be mobilized. For example, residence in Hargeisa is determined by clan affiliation. Different sub-clan communities predominate in specific districts of the city, to the point that specific subclans view government installations in their areas as possessions of their subclan. Even diaspora returnees tend to seek hotels and rentals in areas where their clansmen and women are most concentrated. With a city that identifies through the lens of subclans and a community that still finds security and justice through family and clan structures, Islam is a major unifying and harmonizing ingredient.Footnote 15 This explains the longing to keep this traditionally and religiously inspired public identity free from the corruptions of Western modernity.

In the context of this revered predefined public identity, the invasion of “foreign traditions” as embodied and exhibited in Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse often met with resistance. This yearning for authenticity and authentic identities is epitomized by the quip at the beginning of this article, “These Somalis are not Somalis.” While the statement focused on an element of language—Arabic as opposed to Somali—the overall idea of authentic Somaliness revolves around an Islamic personhood and identity, and encompasses other performative practices including fashion, language, design, and cuisine, with Islam the envelope for all others.

Debating Authenticity in Post-conflict, Postcolonial Hargeisa

Against this background, Somaliland has developed practices of monitoring social interaction for the good of this public identity that is demonstrably predefined according to an Islamic ethic: self-appointed vigilantes, security servicemen, elderly women, clan or village elders, and religious leaders consider it their obligation to ensure the sanctity of Islam in the public domain. The religious leaders are even more powerful, as they have a more elevated platform. During the Friday summons, the imam has the right to criticize any section of society that is deemed to be destabilizing the status quo. Since the religious leaders command a great deal of power and influence for their role in society (see Ducale Reference Ducale2002), their word of disapproval or approval is powerful—and could result in a person’s social downfall. A combination of these practices from different centers of power ensures the sustainability of this predefined public identity. Cup of Art’s apparent transgression of the predefined society ethic as seen by vigilantes—including vigilantes of language and good speech—and security servicemen makes three things apparent: first, a contest between predefined linguistic and Islamic identity, and articulations of identity by Somalis coming from elsewhere; second, the presence of discursive and institutional structures which monitor and enforce the predefined public identity and make sure it is not destabilized; and third, the longing for authentic identities as one of the yardsticks of legitimating belonging and sharing whatever Somaliland has to offer. But what do these claims of and aspirations for authenticity mean for a postcolonial nation-state building afresh after undergoing civil war and large-scale violence? What does this aggressive push and pull between tradition (linguistic and Islamic strictness) and supposed western influences mean in these later stages of postcolonialism, after the original dreams of the anti-colonial struggle ended first in colossal failure (evident in spiralling cases of corruption, civil wars, and re-colonization) and now are manifest as secessionist movements/nationalisms?

In an illuminating essay published in 2013, the Slovenian cultural anthropologist and theorist Rajco Muršič notes that our claims and yearnings for authenticity make us feel good but count for absolutely nothing. They are not only ahistorical but also bereft of conceptual clarity, yet overly charged with negative energy. Muršič begins by acknowledging the powerlessness of the term, noting that “authenticity” has no solid base, as it simply exposes a fascination for items that we see as ‘still resisting’ the aggression by more forces such as colonialism or capitalism. He writes: “In these times where everything solid is ineluctably melting into thin air, the notion of authenticity is widely used to define that which is resisting. However, this resistance is not necessarily liberating” (Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013:47).

This resistance is not necessarily liberating because the world has eternally become more connected through legacies of contact, and that which is “authentic” or original to a group is difficult to define. Muršič continues, however, that the history of the term “authenticity” tends to be found, problematically, in the resistant traits—those that appear not to be changing through the legacies of contact with neighboring traditions, colonialism, or empires. But this is a difficult one, too: How does one determine how much has remained of a tradition, or a piece of music, and how much has changed? Muršič then draws our attention to the motivation behind aggressive claims of authenticity, pointing not just to the uselessness of these notions, but also to the dangers associated with their becoming the “excuse for suppression, repression, prevention and cleansing.” Muršič continues that the tendency has been to use authenticity “to prove ancient rights on land or as constitutive basis for national formation or as the unquestioned kernel of any recognizable social group.” But the intentions are never benevolent: “…it is difficult to find any use of the notion of authenticity that does not provoke harm either as an agent of homogenization or as a tool of exclusion. Its draconian variants may be observed in racism, nationalism and all other kinds of exclusivism” (Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013:46–47).

We need to note here that Muršič, in the first instance, is drawing our attention to the fact that any claims of authenticity often seek to create a wedge between “us” and “them” (Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013:55), which thereby grants access and privileges only those who pass the authenticity test. It then denies the claims of those who fail the same test, yet the terms of the tests have tended to ignore the conditions in which the new variants or corrupted versions emerged. Thus, claims of authenticity serve as technologies “for suppression, repression, prevention and cleansing,” as is the practice in genocide and ethnic cleansing campaigns (see for example, Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns2013). Muršič points to the political economy that is often behind these claims of authenticity. In other words, claims for authenticity are not innocent cultural nostalgia but loaded with material interests, and could serve as the basis for conflict. Thus, he concludes, it is difficult to find any use of the notion of authenticity that does not provoke harm, either as an agent of homogenization or as a tool of exclusion.

Indeed, claims of authenticity often tend to problematically translate into claims of homogeneity of both structure and practice. As seen in Hargeisa’s predefined public, the “real Somali” is defined in homogenized terms, and differentiation is bound to be rejected. So tradition and Islam are being presented not just as one and the same, but also in a homogenous fashion. Yet, as the scholarship on Islam demonstrates, it is a discursive context-specific tradition/religion (Asad Reference Asad2009). Why, then, would a Hargeisan public attempt to homogenize and fix its time and place? Muršič’s identification of authenticity claims as the basis for notions such as racism is worth considering a little more deeply. This would help us problematize the scholarship on Somaliland that praises the hybrid political process as the hallmark of peace in the region (Walls Reference Walls2009, Reference Walls2014; Hansen & Bradbury Reference Hansen and Bradbury2007), on the one hand, yet ignores the discursive ingredients such as cultures and traditions on the other, which are potential causes for conflict. Racism (in this case, authenticity), Muršič notes, “is built on the idea that there is hereditary characteristic of human populations and that pure and authentic genes will become spoiled and destroyed by mixing” (Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013:55). In Hargeisa’s public identity, the fight against alien cultural-social practices common in Somalis born and raised abroad has the potential for dangers that are common with racism. This is evident in the way Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse was constantly attacked, rebuked, and raided, on the grounds of, in Asad’s (Reference Asad2009) parlance, peculiar practices of Islam that are mobilized to sustain a “pure” Islamic identity.

There is another line of analysis that Muršič inspires while discussing authenticity. His beginning point moves the term “authenticity” from claims of autochthony or purity to the relational realm. He writes, “What is authentic to some people is inauthentic to other people…And if everything can be at least in one way authentic, then there is no sense in using the term” (Reference Muršič, Fillitz and Saris2013:48) even if authenticity were understood as place-specific. This way, we appreciate that even in its supposedly original form, what could be perceived as “authentic” is often a product of several earlier moments of contact that could be unknown to the people in the present, and thus claims of originality and purity could be ahistorical, inconclusive, and thereby misinformed. This actually means that claims for authenticity are often a product of unawareness of these histories of contact, which then become manipulated into justification for exclusion and inclusion.

Conclusion

The claims of the un-Somaliness of some Somalis—for their lack of competence/fluency in the Somali language––and the opposition that Cup of Art Italian Coffeehouse received for its allegedly “inauthentic” Somali identity as a café located in Somaliland’s capital should be understood as an indirect route, with the potential for conflict building on cultural/religious and/or linguistic differences. However, it also might end in a contest over resources—with one group being excluded for its inauthenticity. This then imposes upon us a different reading of the context of Somaliland politics and stability, and the essentialism of the present actors insisting on a traditionally defined modernity as a way of resisting foreign values and languages as guarantors for stability. This is problematic as we enter a new phase of postcolonial post-conflict reconstruction, which also includes campaigns of secessionism. If the failure of the Somali Republic in 1991, under whose banner independent Somaliland continues to live, is explained as a failure to accord tradition and religion their due respect, and these two—authenticity in language and religion—are considered the basis for stability and security in Somaliland, this position ought to be understood as problematic, since the original conceptual premise of authenticity is itself a difficult one. We need to be reminded that the war against Siad Barre was a contest over resources (Besteman Reference Besteman1996; Kapteijns Reference Kapteijns2013), although it was oftentimes couched in the language of tradition.

In the age of capitalism and modern nation-states—where the world has become more connected through capitalism, production, consumption, and laborers’ opposition to capitalism (Aijaz Reference Ahmad1992)—traditions involuntarily come into contact with several other traditions, and thus they will often involuntarily remake each other. Actors in this new ‘problem space’ are constrained to interact within this space (Scott Reference Scott2004) and cannot imagine new horizons outside of the conditioning limits imposed by the problem space. To be “inauthentic” in the eyes of the other is never a conscious choice, but a product of conscription—not choosing—to a modernity which could have rendered one “inauthentic.” The political-cultural project of forcefully silencing the fruits of contact through claims of protecting authenticity risks engendering extremism and internecine conflict. This explains why the imagined predefined Hargeisan public is placed in a difficult position regarding how to deal with Somalilanders who are cherished for returning home and investing, but who, at the same time, present a danger to this predefined public identity. As one diaspora returnee from Toronto said to me, “They [kindred] like us for our money, but as soon as we get here, they love to hate us for our appearances and practices.” It is my contention that steps toward peace ought to involve bridging these internal contestations, especially the aspirations for purity of public identity as played out at Cup of Art Italian coffeehouse.