Samuel Felsted has been hailed by researchers and performers of his music as Jamaica's ‘first-documented’ composer, as the author of ‘the first complete oratorio composed in the Western Hemisphere’, and as a ‘true Jamaican’.Footnote 1 Yet, as a so-called ‘creole white’Footnote 2 who was born in Jamaica and who lived at the peak of the slave-trade era, he remains an obscure and ambivalent figure in the island's colonial past. He is still virtually unknown to musicology: the gradual rediscovery of his 1775 oratorio Jonah in the 1980s–1990s and, more recently, the commemoration of the two hundred and twentieth anniversary of his death in 2022 passed with relatively little mention in academic circles, although in the same year a live-streamed concert of some of his works was held simultaneously in Jamaica and Austria.Footnote 3

What is presently known about Felsted is set out in journal articles written by Thurston Dox (an American musicologist) and Pamela O'Gorman (a former director of the Jamaica School of Music). Together they brought the story of Felsted's rediscovery, his biography and his known musical works at the time – Jonah and a set of organ voluntaries – to the academic community.Footnote 4 Dox's remark about Felsted having been a ‘true Jamaican’ might suggest sympathies with ideologies that are linked to Jamaica's post-independence nationalism. Jamaica declared its independence from the United Kingdom on 6 August 1962, and its national motto – ‘Out of Many, One People’ – sets a tone of acceptance and inclusivity with regard to the country's varied history leading up to that point. But Dox was writing over thirty years ago, which, incidentally, was around the last time Felsted received serious scholarly attention.

The fact is, neither Felsted's heritage (which is indisputable) nor the detail that he happens to be Jamaica's ‘first composer’ – that is, the first on record – make him particularly remarkable.Footnote 5 There is currently a rising public interest in better documentation of the history of the slave-trade era and its present-day implications. Following the start of the Black Lives Matter movement and the widespread efforts for decolonization that it has sparked, Commonwealth nations like Jamaica are seeking a different kind of relationship with their former colonial power. Even though Felsted was ‘a true Jamaican’, the time is ripe, today, to reconsider what makes him relevant and noteworthy as a historical figure.

Current projects that aim to assert the relevance of Felsted's musical, cultural and historical legacies must evaluate him in isolation from the ideological pressures of Jamaican nationalism. Likewise, musicologists need to resist the temptation to situate his music simplistically within the ‘fringes’ of the canon of Western art music. There is little unique about the sound of Felsted's music. It is devoid of the kinds of African elements that might make it identifiable as Jamaican, and it draws, instead, emphatically on the musical idioms of urban eighteenth-century Britain. Stylistically, Felsted's music is reminiscent of the church and stage works of his English contemporaries such as Thomas Arne, Samuel Arnold and William Shield. It also draws from George Frideric Handel (reflecting the increasing reverence for his works in the decades after his death in 1759) and from Continental composers who emigrated to or sojourned in Britain like Tommaso Giordani and Johann Christian Bach. In its sonic values, Felsted's music is inherently British. Yet, as I explore in some detail below, archival materials surrounding the composer's life link his music unequivocally with the location in which it was conceived, and this is what I would argue makes it interesting. His little-known second oratorio The Dedication is especially important because of the connections that can be drawn between the text's themes and Felsted's social context.Footnote 6 This work survives in the British Library as a neatly handwritten and full orchestral score bound as a single volume and written on eighty-three folios; it does not bear a date.Footnote 7

This article does not offer a detailed musical analysis,Footnote 8 nor is it a political critique of the design of music curricula. Rather, I will explore a different model of colonial music historiography by reconceptualizing Felsted's life and by contextualizing his oratorio The Dedication in the process. At the time when Felsted lived in and around Kingston, the Jamaican economy was underpinned by profits accrued from the sale of enslaved people of African origin and products derived from their coerced labour, mainly connected with the manufacture of sugar.Footnote 9 Enslaved people and their descendants made up the overwhelming majority of the Jamaican population. But the topic of Felsted's connection to his black contemporaries has continued to be carefully sidestepped by scholars of his life and performers of his music alike. As a musicologist of black British and specifically Jamaican heritage, I want to know more about how Felsted's music demonstrates his sources of influence and how he benefited from living in a society that was made up of people of African descent who were reduced to mere chattels.Footnote 10

This article, therefore, takes the opportunity to offer a more complex and multiply informed evaluation of Felsted's life and output. I use an anti-colonialist lens to visualize this man and his social environment through a kind of ‘black gaze’.Footnote 11 That is to say, my historicization of Felsted is fixated on the indefinite, yet palpable black presence surrounding him and his activities. My choice of the term ‘anti-colonialist’ here refers to the lens through which I approach the colonial music archive. It is intended to acknowledge, but also to create, a distinction from the work of decolonization, which, I would argue, is not possible in the context of a colonial composer such as this one. My aim is to write about Felsted, his music and his colonial context in ways that minimize the risk of reinscribing the harmful effects and perspectives of colonialism.Footnote 12 Rereading the colonial music archive ‘along the bias grain’, this article attempts the long overdue task of exploring the extent to which it is possible to reverse the erasure of the black presence in Felsted's biography.Footnote 13

The relevance of Jamaican music history to global issues of African slavery and the rise of capitalism has featured in the work of scholars of various disciplines, and this article contributes to discussions recently set out by David Hunter, Maria Ryan and Mary Caton Lingold.Footnote 14 Prior to their work, European musical culture in late eighteenth-century Jamaica had been examined by only a handful of scholars.Footnote 15 The most informative overview of the music of the time and place was provided by Richardson Wright, in his book Revels in Jamaica (first published in 1937).Footnote 16 Yet this work, as well as the two monographs that followed it – Ivy Baxter's Arts of an Island (1970) and Errol Hill's The Jamaican Stage (1992) – are all dominated by discussion of historic Jamaican theatre. They neither contain detailed references to sacred music nor mention Felsted.Footnote 17 In fact, the only detailed source of information about the music of the Church of England in eighteenth-century Jamaica is a ten-page segment of Richard Minter's Episcopacy without Episcopate (1990).Footnote 18 Minter's study is important because it contains an overview of church-vestry accounts held at the Jamaica Archives and Records Department that are now too fragile to be consulted.

What follows is structured in three parts. In the first part I sketch some relevant information about life in late eighteenth-century Kingston. In the second, I set out details about some of Felsted's connections to non-whiteFootnote 19 Kingstonians, focusing on people of African and Afro-European descent. Then, in the final part, I show why Felsted's Dedication might reveal details about how he was influenced by his environment, and the seismic political change that Jamaicans witnessed around the time of the Haitian Revolution.

Eighteenth-Century Kingston

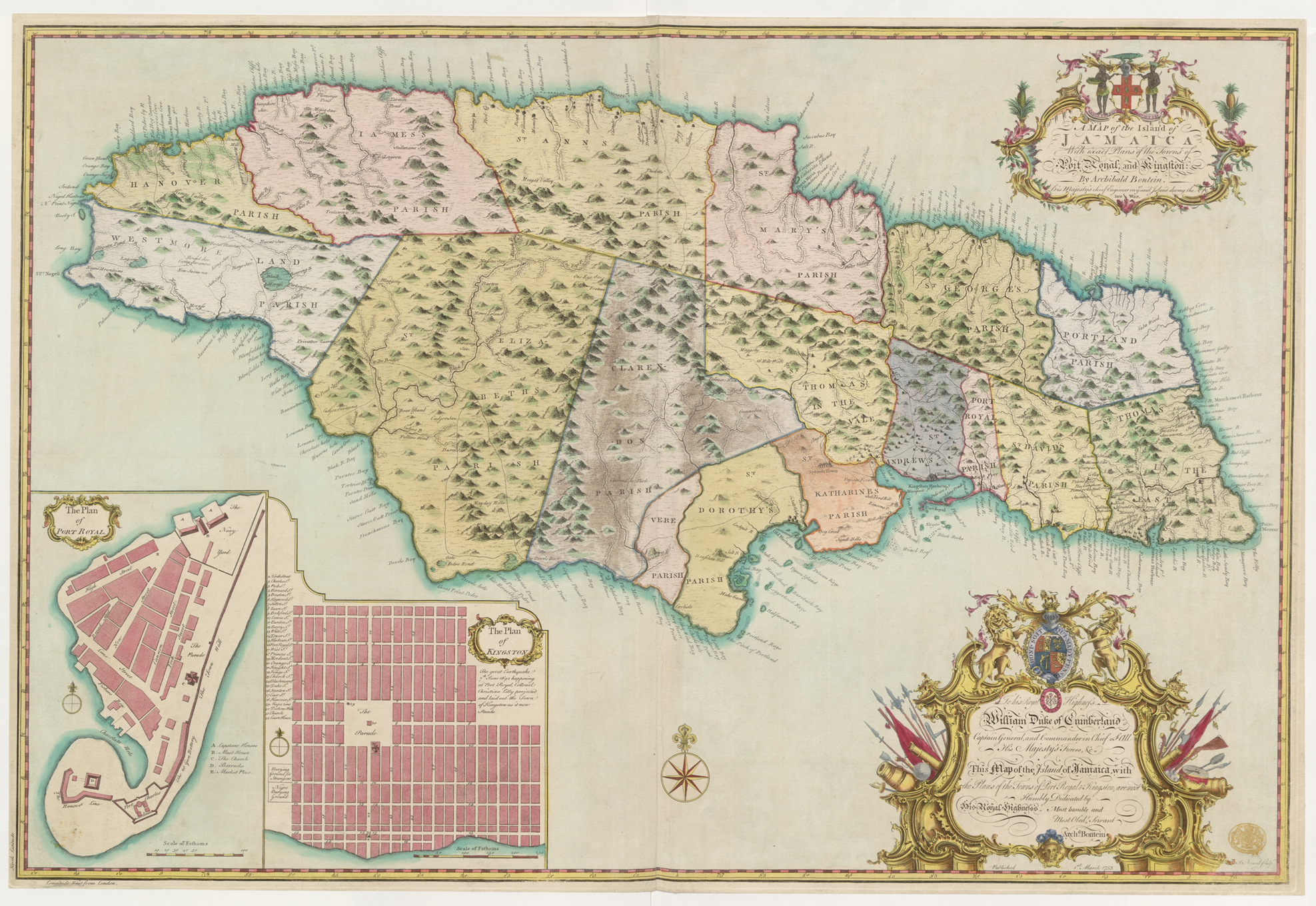

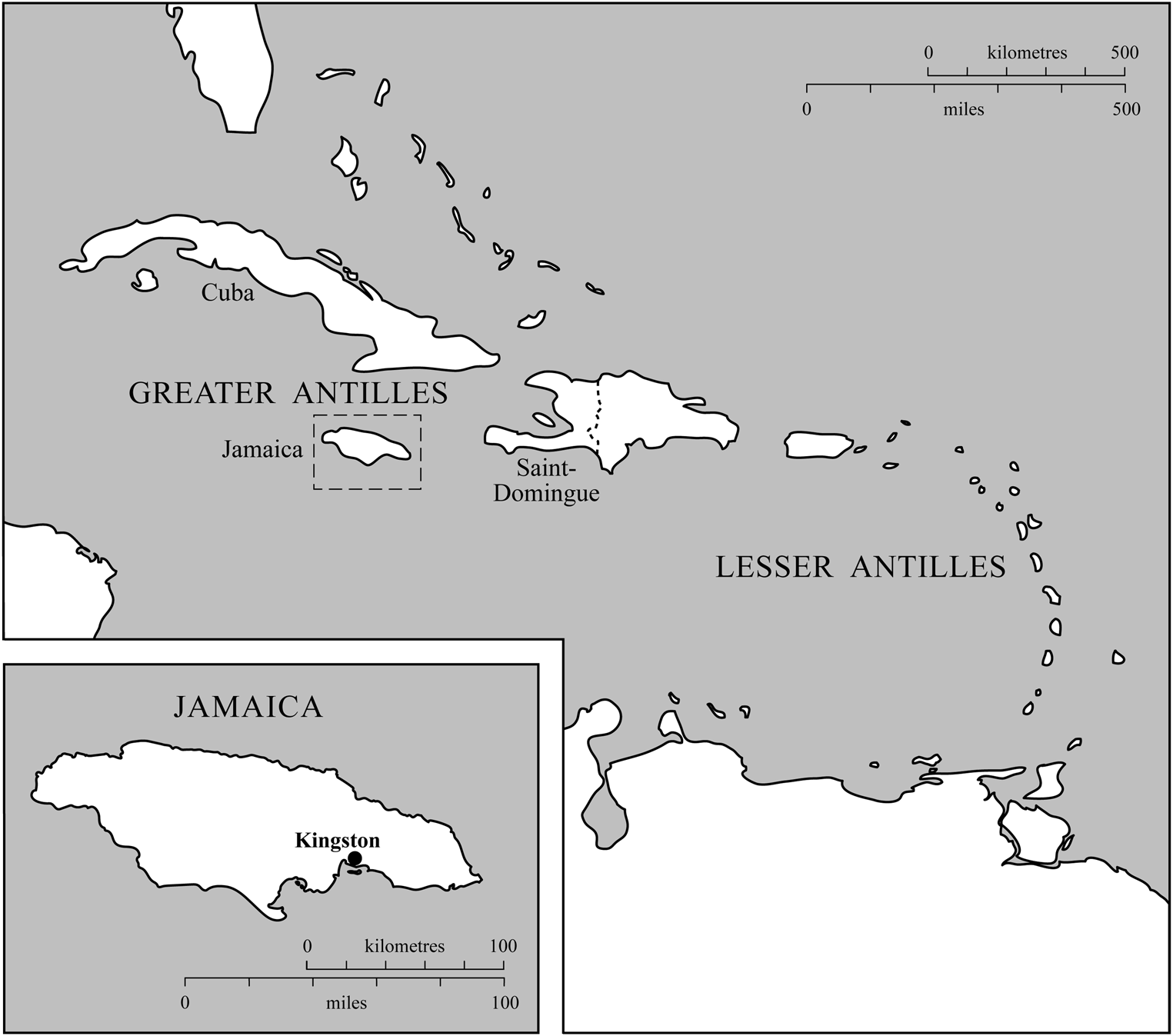

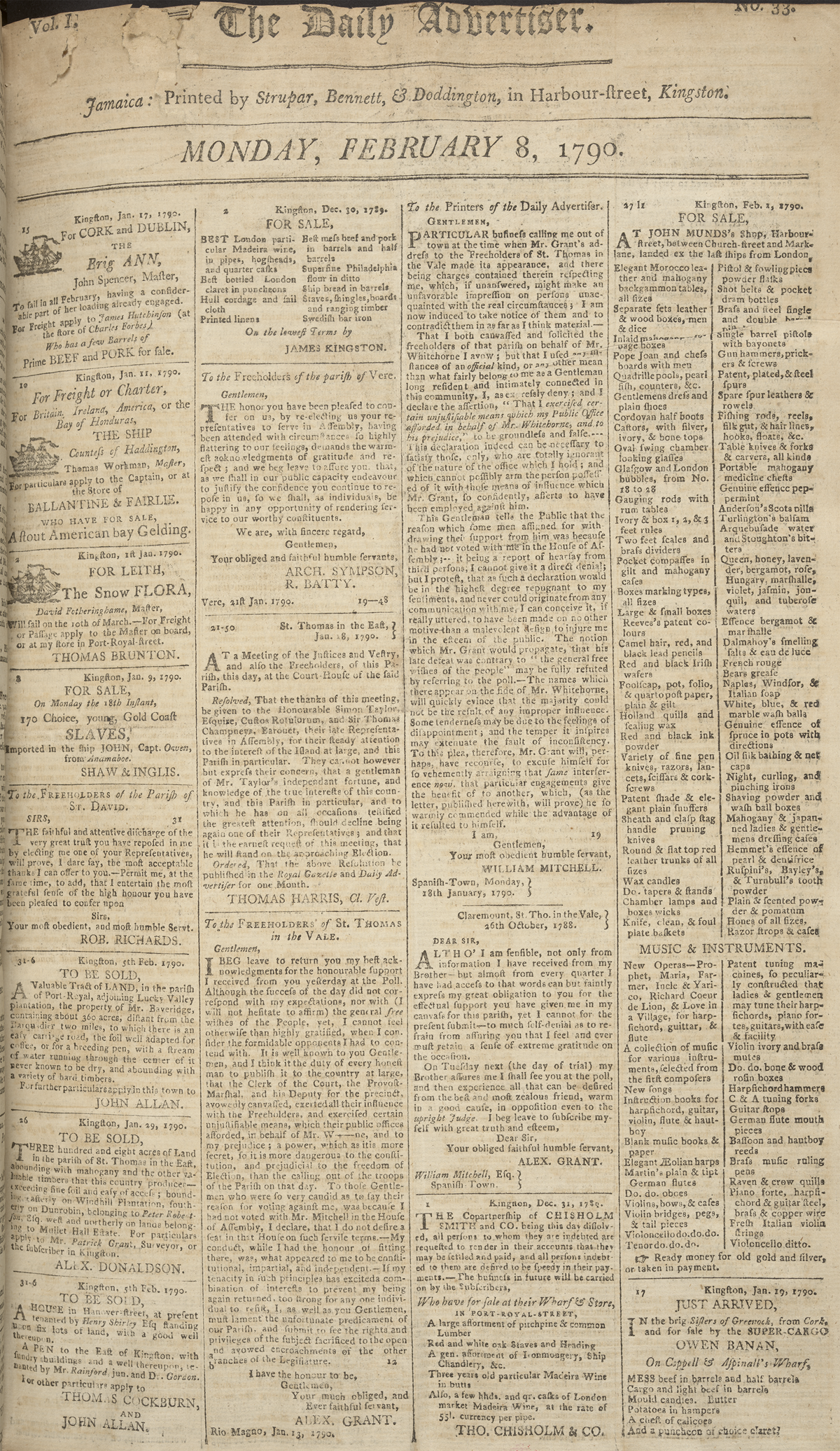

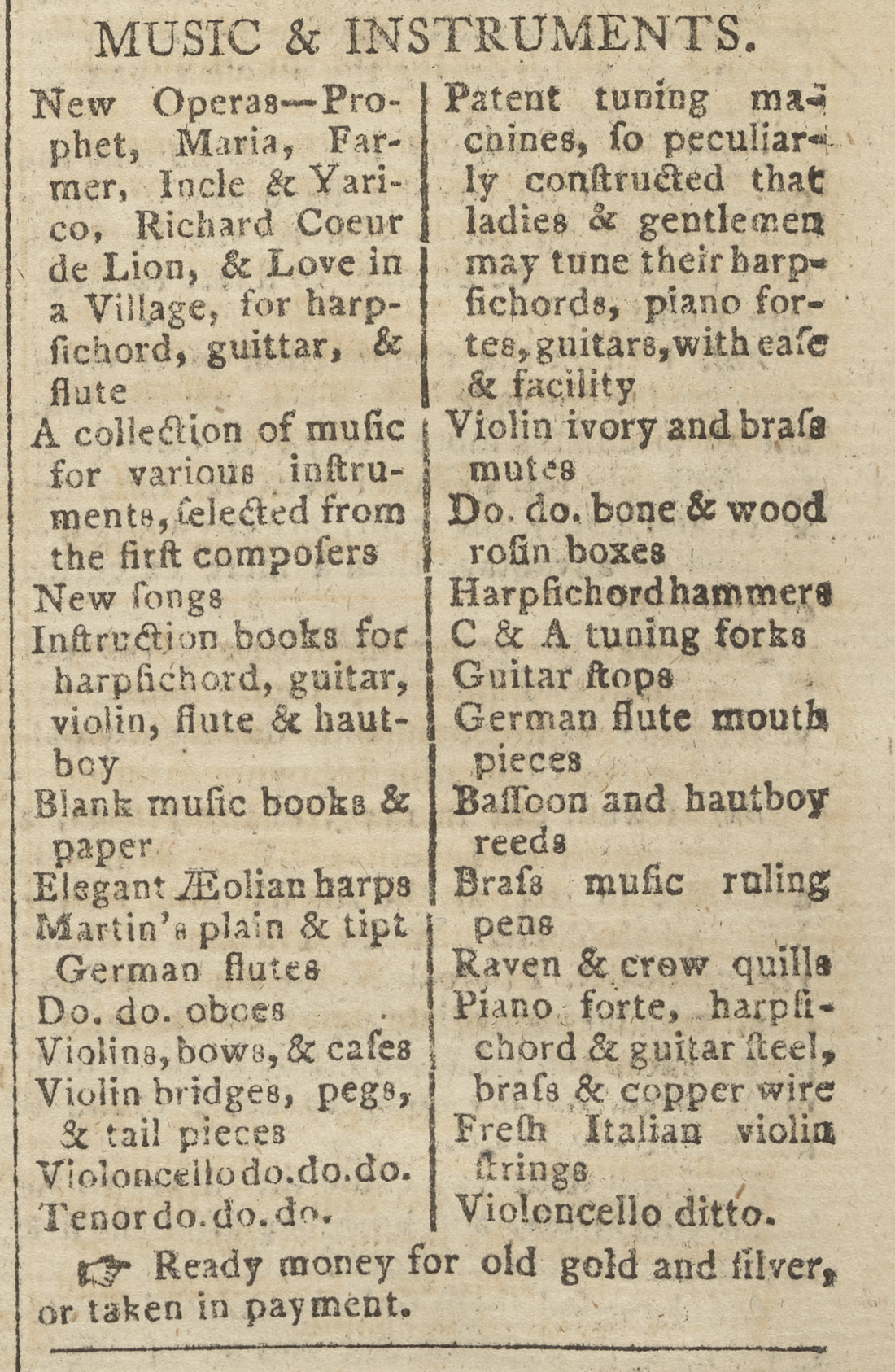

Located in a natural harbour on the south coast of Jamaica (see Figure 1), eighteenth-century Kingston was a kind of social crucible. Home to ‘blacks, browns, Jews and whites’, a ‘cacophony of voices’ and a ‘jumble of complexions’, eighteenth-century Kingston had the largest enslaved population in Jamaica and was the ‘fourth largest town in the British Atlantic’.Footnote 20 For the period between 1774 and 1789 Jamaica's total population has been estimated at 250,000, with around ten per cent of that figure (26,000) making up the number of Kingston's inhabitants.Footnote 21 This made it comparable in size with New Orleans at the time,Footnote 22 but Kingston's many more enslaved persons (estimated to have been 16,659 around 1788) would have made its look and feel altogether quite different.Footnote 23 As the chief port in the anglophone Caribbean, Kingston sat at the centre of Britain's vast commercial and trading network in the Americas (see Figure 2). Day by day ships arrived bringing precious cargoes of food, clothing, stationery, books, music and news, and carrying passengers both European and African, free and enslaved. Announcements and ‘for sale’ notices were published in local newspapers such as The Daily Advertiser (examples of which can be seen in Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Archibald Bontein, A Map of the Island of Jamaica (1753), The British Library, Maps K.Top.123.50. © British Library Board. Used by permission

Figure 2. Map showing Jamaica and Kingston in their broader geographical contexts

Figure 3. Cover page of The Daily Advertiser (Kingston, 8 February 1790). © British Library Board (PENN.NT328, fol. 64). Used by permission

Figure 4. Cover page of The Daily Advertiser (Kingston, 8 February 1790), detail

Away from the busy harbourside, the northern part of Kingston – close to Half-Way Tree (a town in the neighbouring parish of St Andrew) – was a comfortable home for some of the colony's wealthiest merchants. But Jamaica was still a hostile place. While blacks were either subjected to brutal regimes of slave labour or marginalized as so-called ‘free’ citizens, whites lived in constant fear of death at the hands of black rebels, tropical disease and Jamaica's supposedly degenerative climate.Footnote 24 Inevitably, the sensation of displacement was also felt by some of the black inhabitants, who, longing to return to their homelands, reportedly composed songs about their captivity and the absenteeism of their white owners.Footnote 25 An example of one such song was printed in the book West India Customs and Manners by J. B. Moreton, as follows:

Because of the various challenges that their host environment presented, many of Jamaica's white inhabitants imagined the island as a temporary place of residence. Acknowledging this helps to underline why, at the time, they appear to have looked beyond Jamaica for sources of their culture. As Trevor Burnard has explained, ‘the colony was full of transients with relatively little commitment to developing a coherent community ethos and collective identity in the ways that happened in established colonies of British North America’.Footnote 27

Nevertheless, Kingston was home to a thriving commercial European music scene.Footnote 28 It was underpinned by the efforts of entrepreneurs such as the shop owners James Costard (died 1775) and John Munds (1760–1821), military musicians like Henry Andrew Francken (c1720–1795) and sojourning actor-singers including David Douglass (c1720–1786), Lewis Hallam (1740–1808) and James Mahon (fl. 1767–1799).Footnote 29 Most of the surviving details about day-to-day musical performances relate to the ballroom, concert hall and theatre.Footnote 30 Specific evidence of Felsted's involvement with the Kingston theatre has not survived. Nevertheless, evidence that he was influenced by the theatre can be deduced from the fact that each of the six scenes of The Dedication opens with a brief but detailed note about staging.Footnote 31 Felsted's dramatic stipulations are likely to have been influenced by the oratorios of Handel, which were known in Jamaica at the time.Footnote 32 It is also known that Felsted owned manuscripts produced by Handel or his copyists.Footnote 33

Though they are the easiest people to trace in the archive, the white male musicians of eighteenth-century Jamaica (such as those named above) did not exist on their own. They had wives and families who were also musically active. They were attended by servants and slaves of African and mixed heritage, and many white males were the fathers of illegitimate children of mixed ancestry.Footnote 34 Very few non-white Jamaicans were able to transcend the boundaries that were imposed by the white male property-owning society; slaves were only manumitted in exceptional circumstances, by private acts passed by the island's governing assembly. The only portion of Jamaican society to see any natural growth during the period in question was the racially mixed ‘people of colour’ group. Meanwhile, around the end of the American Revolution, Kingston's black population as a whole was bolstered by newly arrived evacuees, many of whom had been granted their freedom by fighting as part of the loyalist campaign. In the following section, I will explain some of the links between Felsted and his black contemporaries living in Kingston. These connections existed through enslavement and its related social contexts but also through Felsted's religious and military associations.

The Afro-Jamaican Presence in Felsted's World

It was into the cosmopolitan environment that I have sketched out here – with all its dynamics of white privilege, power imbalances, racial inequality and black subjugation – that Samuel Felsted's music was born. The oratorio Jonah, which Felsted described as his ‘first attempt at composition’, was probably completed and sent to London for publication sometime in 1774. At this point, Felsted was serving as the organist of the St Andrew Parish Church in Half-Way Tree,Footnote 35 a role he had assumed after his father's death in 1767.Footnote 36 The cost of publishing Jonah appears to have been met by a subscription of more than 240 individuals, who collectively ordered over 280 copies of the work, to be printed by Longman, Lukey and Broderip of Cheapside, London.Footnote 37

It is unknown whether any of the subscribers were people of colour, though several were parents of children with mixed Afro-European heritage.Footnote 38 Hugh Clarke, probably a relation of Dugald Clarke (died c1798), could have been one such non-white subscriber. Dugald Clarke – a self-identified ‘free mulatto’ – was an engineer and inventor who had been granted special rights as a ‘free person of colour’ by a private act passed by the Jamaican Assembly in 1772.Footnote 39 Effectively this meant that Clarke's race was rarely mentioned thereafter. However, despite his freedom and special privileges, a reference in Robert Hibbert's diary to an occasion when he and others ‘declined an invitation from Livingstone in consequence of his hav[in]g. expressly excluded Clarke on acc[oun]t. of his colour’, illustrates the kind of social stigma that Clarke still faced.Footnote 40 Though Felsted's link with Hugh Clarke is uncertain, it is plausible that his interests in engineering and invention would have led to encounters with the Clarke family.Footnote 41

During his tenure at the St Andrew Parish Church, Felsted set about producing an oil painting of a townhouse owned by Emanuel Baruh Lousada (Figure 5).Footnote 42 His name and the date of 1778 are clearly noted in the lower left-hand corner (see Figure 6). Details about the connections between Felsted and Lousada have not survived, but the latter was a merchant of Jewish-Iberian heritage and a prominent member of Kingston's Sephardic community. His house stood on the road linking Kingston and Half-Way Tree (Felsted's hometown), and it is likely to have been a building that Felsted passed frequently. The composer's artworks provide a helpful stimulus for thinking broadly about the kinds of non-white people that might have been involved with his music or affected by it. What is important about the Lousada painting for me here is not the house, its imposing point of focus. Rather, it is the two black figures – a coach driver and the attending page – whom Felsted captured in the lower right corner of his work, and the opportunities they afford for what Saidiya Hartman has termed ‘critical fabulation’.Footnote 43

Figure 5. Samuel Felsted, A North-East View of the House of Mr Emanuel Lousada (1778). Private collection; courtesy of Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York. Photograph by Eric Baumgartner. Used by permission

Figure 6. Felsted, A North-East View of the House of Mr Emanuel Lousada, detail

Dwarfed by the house, the two figures are depicted in motion, appearing – quite unlike other contemporaneous illustrations of blacks – to bustle purposefully into the frame.Footnote 44 Dressed in bright blue house livery, they ride on a beautifully decorated carriage (Figure 7). Felsted's choice to portray these men could have reflected an artistic convention: they might simply have been intended to allow the viewer to gauge the scale of the house. However, it is also conceivable that they were known to him personally. Perhaps they were free people of colour who, in another context, formed part of a local militia regiment. They might have attended the sorts of mustering ceremonies that Felsted was required to superintend from 1782 as Kingston's Deputy Mustermaster-General.Footnote 45 The driver and page might also have been musicians themselves, performing as drummers or trumpeters.Footnote 46 Perhaps, on the other hand, they were enslaved domestic servants attached to the Lousada household and, as part of their duties, were required to convey their owners to concerts, operas and assemblies.Footnote 47 It is reasonable to assume that while waiting outside for their owner's return, they overheard whatever music was going on inside. They therefore could also have been present when Felsted's oratorio Jonah was performed for the first time.

Figure 7. Felsted, A North-East View of the House of Mr Emanuel Lousada, detail

Whilst Felsted's painting of the Lousada mansion brings the question of his relationship with the local black inhabitants into high relief, there are various other kinds of link to be drawn. Felsted, like various members of his extended family, was a slaveowner. His ownership of slaves is mentioned in his will, which he signed on 29 May 1797.Footnote 48 Of these people, Felsted singled out one – a woman named Patience – for special mention. Felsted explained that his slaves could, if necessary, be sold in order to repay his outstanding debts after his death but in ‘acknowledgement’ of her continued ‘attention’, Felsted bequeathed Patience to his wife. The document does not contain further details about Patience beyond the fact that she had nursed Felsted through an illness that he referred to as a ‘long continued indisposition’.Footnote 49

Margaret Felsted, a ‘free black woman’ who was baptised in Kingston in 1806, is another person whose enslavement bound her to the Felsted family.Footnote 50 Her birth year (c1741) is close to Samuel Felsted's (1743) and her name is strikingly similar to that of his wife, who appears variously in historic documents as Margaret, Mary (in the list of subscribers to Felsted's Jonah) and Maria.Footnote 51 The Kingston slave register for 1817, for instance, documents a woman named Margaret Mary Felsted as owning thirteen slaves.Footnote 52 Dox identified Felsted's wife as ‘Maria Laurence’ the daughter of Richard Laurence (a Jamaican estate owner), which might lead historians to the conclusion that she was a white woman.Footnote 53 However, a manumission record for ‘Mary’ – also referred to by the name ‘Maria’ – that dates from 1762 explains that her freedom was secured by Felsted's father, William, for ten shillings in the local currency.Footnote 54 Could this formerly enslaved woman have become Samuel Felsted's wife? Or could she have been the illegitimate child of William Felsted and a woman of African heritage?Footnote 55 Perhaps the simplest answer is that the woman's former owner granted her permission to pay William Felsted to arrange and oversee the process of her manumission. In any case, it is clear that the woman was closely connected to the Felsteds, if only through the act of her emancipation.

In his role as the organist of Kingston Parish Church, to which he had been appointed in 1783,Footnote 56 Felsted would have performed from the church's west-end gallery (an acoustic vantage point). This space would have been peopled by the Afro-Jamaican congregants during services.Footnote 57 The conspicuous presence of African-descended worshippers would have been a familiar aspect of the weekly Divine Services that took place in Jamaica's spaces of Anglican worship. In the words of one Jamaican rector living during Felsted's lifetime, ‘on Sundays the people of Colour make three fourths of my Congregation, nay, many times I would not have A Congregation without Them’.Footnote 58 The fact that it has gone undocumented in archival sources does not preclude the likelihood that Jamaican organists such as the Felsteds performed the labour of psalm and hymn accompaniment from within an acoustic enclave of black singing. Could the organists have provided musical instruction for the black congregants as they were sometimes required to do for the ‘poor children of the parish’?Footnote 59 Could a version of the English church-gallery choir have existed in the black space of Jamaica's pre-emancipation organ loft?Footnote 60 The surviving sources do not offer concrete evidence to answer these questions. But they do allow us to imagine how, with their supposed ‘good ears’ for ‘tune and time’, worshippers of African descent – at least in the minds of whites – learned hymns and psalms quickly. Singing from memory, they would likely have performed this church song in their own characteristic manner.Footnote 61

Writing in the 1760s and early 1770s, Edward Long (1734–1813) – the pre-eminent historian of Jamaica at the time – explained that municipal organists were generally required to play for the funerals of non-white Christians, and they received additional pay on top of their reasonable up-to-£130 salary for doing so.Footnote 62 In Jamaica, Christians who were black appear to have been laid to rest in the same burial grounds as those who were white.Footnote 63 And church sextons, like Samuel Felsted's father (who was also an organist), were paid per burial.Footnote 64 The Kingston vestry's mandate of 1781 – that ‘the Church Bell’ was to be tolled for ‘no longer than five Minutes’ unless for funerals ‘of white persons’ – implies that the bell might have been deliberately rung for people who were not white for long periods.Footnote 65 Whether enslaved or free, Kingston's bellringers were probably people of colour.Footnote 66 Kingston Parish Church could, therefore, have become a kind of contested space in which certain aspects of white hegemony might become distorted or even deliberately subverted by certain acts of black autonomy.

Given that Felsted was ‘baptised an Anabaptist in 1763’, his personal faith also probably brought him into proximity with George Liele (1750–1828) and other Anabaptists of African descent who were part of the church he established in Kingston around 1783.Footnote 67 Liele was a free black man who, having arrived in Jamaica after the evacuation of Savanna in 1782, held a variety of professions. These included being a militia trumpeter and a preacher.Footnote 68 Given their military and religious associations, and the fact that Liele seems to have been known to Felsted's brother-in-law, Stephen Cooke,Footnote 69 Felsted and Liele may plausibly have been acquainted.

Further evidence of Felsted's connection to the black community in Kingston can be found in newspapers detailing the events surrounding his dismissal (or resignation) from the post of organist at Kingston Parish Church in late 1790.Footnote 70 Newspaper articles published around this time mentioning Felsted's name seem to portray him as a public figure, a kind of philanthropist, called upon to arbitrate on the behalf of an unknown individual in a dispute over the use of funds by the trustees of the local free school. In the Daily Advertiser issue of 7 October 1790, there appeared an anonymous article entitled ‘Certain Questions to Certain Persons’ and signed ‘A. B. C’. This text publicly criticized the Wolmer's School board – an act which must have met with the consternation of the rector of the parish at the time – and also the local assembly for their poor handling of ‘disserted, sick, disabled and aged negro and other slaves’.Footnote 71 It is telling, then, that when Felsted was summoned to answer to the Kingston vestry at the local courthouse (on 9 October 1790), he sought to assert his rights as a free subject of the king, ‘free to think, or act as any of themselves’.Footnote 72 In the summary of court proceedings that was published in the Daily Advertiser on 18 October 1790, Felsted ‘voluntarily, acknowledged that he was the author of the Queries inserted in the Daily Advertiser of the 7th inst’.Footnote 73 Later (on 22 November 1790), the Daily Advertiser published a column titled ‘Origin of the Asylum’ that contained a list of twenty male and female slaves who had been left to perish on Kingston's streets from January to November of that year. Felsted's name appears in block capitals underneath letters calling for support to remedy what is described as a ‘growing evil’ and declaring it ‘a disgrace . . . th[at] this nu[i]s[a]nce has been so long suffered [t]o exist . . . a disgrace to our police, as well as to our feelings as men, for the sufferings of our fellow creatures’.Footnote 74 Notably, the texts refer to the slaves as ‘miserable wretches . . . superannuated and past labour’ and, in an uncommon reversal of the language of the time, their owners are branded as ‘inhuman’.Footnote 75 In using the word ‘nuisance’, however, it does not seem as if the author is describing the individuals as such, but rather the situation as a whole. Of course, this kind of ambivalence in the sources relating to Felsted does not allow us to make an absolute judgment about his relationship with people of African descent in Kingston.

It is not clear what other grievances were brought against him in the days that followed, but Felsted's post as organist was advertised in the same newspaper that set out the information about his court appearance, and by January 1791 it is clear that he had been replaced.Footnote 76 It is likely that, as a municipal organist, Felsted was viewed by the vestry as a public servant. He might simply have been dismissed because his outspoken views struck defiantly at his employers (the vestry) and at the centre of the very establishment of which he was ostensibly a part. It is with these contexts in mind that I will now show how Felsted's non-white and Afro-Jamaican connections might have inspired and influenced his composition of The Dedication.

Slavery, Freedom and The Dedication

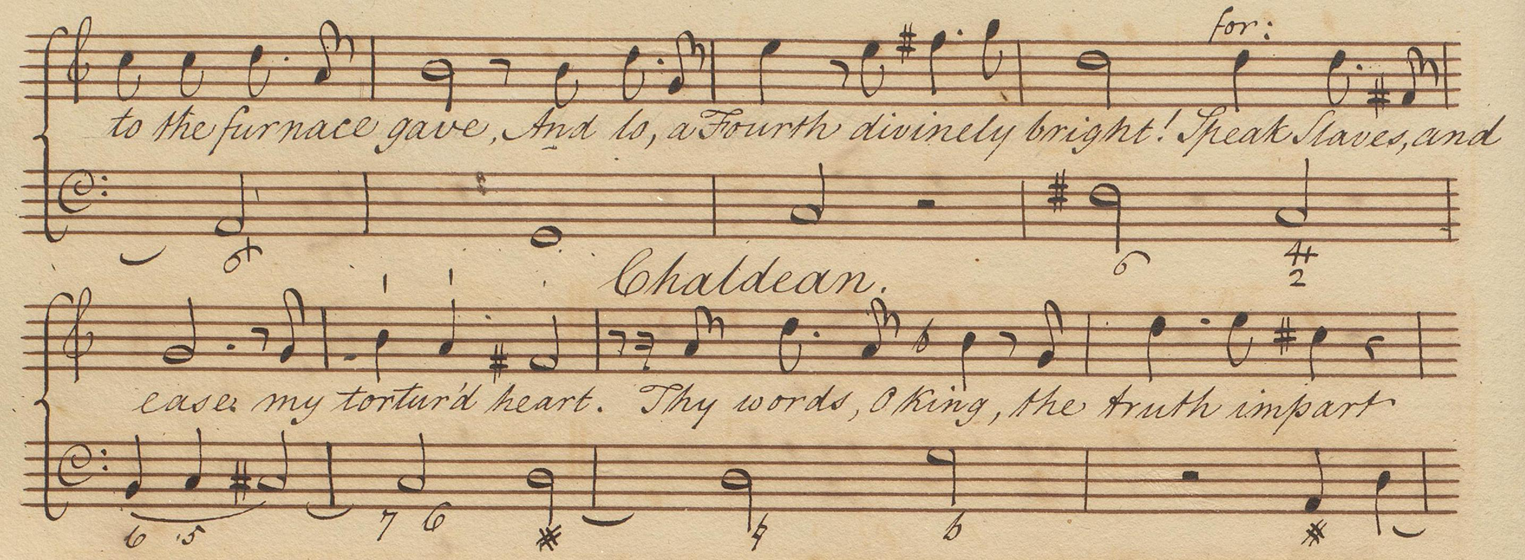

Set in ancient Babylon, Felsted's Dedication is an adapted and poeticized version of the Old Testament narrative about Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah (friends of the prophet Daniel), and their condemnation to death in a furnace. The sentence was handed down by King Nebuchadnezzar II as punishment for the men's refusal to worship his idol (such a practice is forbidden by Jewish law).Footnote 77 Seeing their religious devotion, God took pity on the men and sent an angel who appeared beside them inside the furnace, ‘divinely bright’ (to quote Felsted's text; see Figure 8).Footnote 78

Figure 8. Samuel Felsted, The Dedication, The British Library, R.M.21.f.2, 110 (fol. 127v). © British Library Board. Used by permission

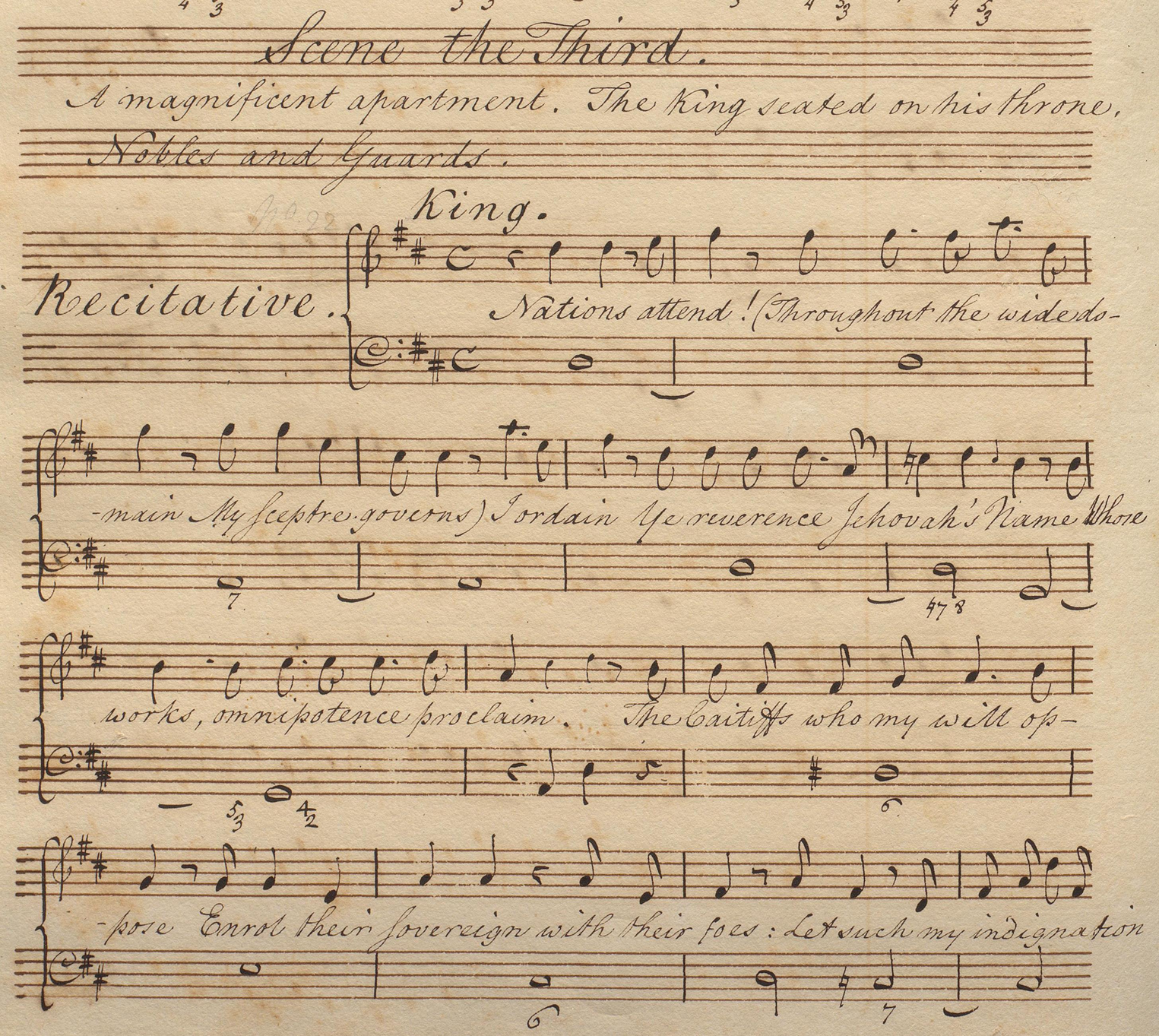

Astonished by their survival and convinced of God's intervention, the king called for the men to be released and promoted them to the highest positions within his court. Then he made the proclamation (as set by Felsted; see Figure 9) that all his subjects ‘reverence Jehovah's Name, Whose Works omnipotence proclaim’.Footnote 79 The essential message of the text thus invites its audience to follow God's commandments and to put their trust in him. After all, it was precisely their trust in God that had saved the Israelites in their time of greatest peril.

Figure 9. Felsted, The Dedication, 120 (fol. 137v)

Rather than its sonic properties, what resonates most with Felsted's world in The Dedication is the biblical material on which his libretto is based, and this is where we must look in order to consider the significance of the work within the social contexts in which it was produced. Babylon's Israelite inhabitants – like the many Africans who arrived on the Jamaican shore in Felsted's lifetime – were captives. Once removed to Babylon they were renamed.Footnote 80 Daniel, who was a prince (and thus a royal captive), and his three friends were all highly educated. Their experiences were less severe than those of the other Jewish exiles. For instance, rather than working as labourers, they were allocated roles within the Babylonian administration. Meanwhile, the rest (who were coerced labourers), were forced to live in hardship and were thus essentially slaves. The fact that the king refers to the Israelites as slaves at various points in the libretto makes it clear that Felsted intended for them to be perceived as such.

Although influential Jamaicans attended churches, prayer houses and synagogues, surviving sources offer few explicit suggestions that they made comparisons between biblical depictions of slavery and the kind that existed in their own world. Nevertheless, Felsted's decision to compose an oratorio based on the book of Daniel – the narrative of someone who could be considered akin to a slave, being a captive and an exile – might have been motivated by several factors. Felsted may have taken inspiration from people living around him (such as those I have already mentioned), people who had lived (or were indeed still living) in Jamaica who were said to be descended from African royalty, and people who were written about in the British publications that were read in Jamaica.

An example of a text about an enslaved person of African royal descent that was known in Britain during the period in question is Aphra Behn's tragic novella Oroonoko (1688). Having been adapted for the stage, the work was performed for the first time in London in 1695. Oroonoko may have been the earliest source of the Royal Slave trope (in anglophone literary sources), but one of the most popular ballad operas that was performed in Kingston in Felsted's own day was Inkle and Yarico (1787) by Samuel Arnold (1740–1802) and George Colman the younger (1762–1836). In this work, Yarico, an Indigenous woman (who might have been portrayed as an African princess in later stagings), falls in love with an English sailor named Thomas Inkle, having rescued him from a shipwreck. Though the two are supposedly in love, the plot takes a sinister turn when the money-thirsty Inkle wickedly conspires to sell Yarico and their unborn child into slavery.Footnote 81

In addition to the examples already mentioned, Felsted may have learned of the real-life and widely publicized (though exceptional) case of William Ansah Sessarakoo (c1736–1770), who, having escaped enslavement in Barbados, travelled to England, where he was ushered into the metropolitan elite.Footnote 82 Another example, the child-prodigy violinist George Bridgetower (1778–1860), was reported in newspapers announcing his first public concerts in England in late 1789 and early 1790 to be the grandson of an African prince.Footnote 83 A further example of a person descended from African royalty who was discussed in the metropolitan literature of Felsted's day is Toussaint Louverture (1743–1803), undoubtedly because of his central role in the Haitian Revolution (c1789–1804).

It is worth considering whether the developing crisis in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) in the late 1780s and early 1790s might have been a source of motivation for Felsted to compose The Dedication, especially since many Jamaicans were, in fact, better informed of the events than the local newspapers of the time suggest.Footnote 84 With regard to Felsted's motivations, I am referring to three issues in particular. The first concerns the various kinds of trial and suffering (particularly those involving fire) that occurred during the conflict. Felsted's decision to preface the score of The Dedication with biblical passages referring to ‘the fiery trial’ and ‘sufferings of this present time’ (see Figure 10) resonates as much with the real-life trials of the various disenfranchised inhabitants – the ‘poor whites’, ‘slaves’ and ‘free blacks’ – of late eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue (and Jamaica) as with the plot of the oratorio.Footnote 85 Although I am highlighting the events of the Saint-Domingue Rebellion in this article (because of its particularly wide-reaching impact on the Jamaican society), various other disturbances could have led Felsted to compose The Dedication. These include several fires that broke out in Kingston in the 1780s and the particularly devastating fire that left most of Montego Bay ‘reduced to ashes and bare walls’ in 1795.Footnote 86 The latter anticipated a large-scale rebellion of the Maroon communities living nearby.Footnote 87

Figure 10. Felsted, title-page of The Dedication, fol. 3r

Though the possibilities are numerous, the fact that Felsted felt the need to assert his own freedom during his courthouse appearance suggests that he could have been aware of the worsening situation in neighbouring Saint-Domingue and, in particular, traumatic events like the burnings of Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien) of August 1791 and June 1793.Footnote 88 Though Felsted was reasonably well paid, he too was a ‘poor white’, and as such may have sympathized in various ways with his neighbouring colonists in Saint-Domingue.

Another issue related to Haiti concerns the fact that the rebels were eventually led by Toussaint Louverture. Louverture was a devout Christian, and, reportedly, a former slave descended from African royalty. As such, his fame stretched across the Caribbean, and he was known to Jamaican colonists.Footnote 89 Both this point about Louverture and my final point on this matter – the collective faith of the black insurgents – are related. Being enslaved or the descendants of slaves, the insurgents in Haiti were initially concerned (like the author of the articles undersigned by Felsted in the Daily Advertiser) with securing better treatment.Footnote 90 A letter that they addressed to the governor of Saint-Domingue in 1791 set out their compulsion to trust that ‘God who fights for the innocent [would be] their guide’, in precisely the way that God had guided the Israelites in the various scenarios of the Old Testament.Footnote 91 It is telling that when the rebels chose to express themselves, they did so in a manner that was so heavily steeped in biblical – and specifically Old Testament – rhetoric.

It is because of these various resonances that I suggest that Felsted composed The Dedication during the early 1790s. Of course, while oratorios appear to have been scarce in the British American colonies of his day, Felsted was the not the first composer to turn to the Bible in order to create some kind of commentary on the world in which he lived. Handel's oratorios, for instance, might have conveyed similar political themes.Footnote 92 Such ideas could, of course, be dangerous to express at the time, which might explain why The Dedication seems not to have received any public attention in the composer's lifetime. One possible explanation for why the piece ended up in England as a neat manuscript might be because it was sent for publication in London, like Felsted's earlier works.

Concluding Remarks

I introduced Samuel Felsted at the start of this article with a critique of some of the accolades that were apportioned to him when his first oratorio, Jonah, was rediscovered in the late twentieth century. Although meaningful on a surface level, these kinds of tributes reveal little about what I would argue is the real importance of Felsted's historical legacy. What they do show us, however, is that Felsted has been valorized in ambivalent, elitist, nationalistic and specifically Eurocentric terms in the past.

As part of my exploration of his pertinence to today's music historians, I have offered a new kind of biographical study of Felsted: in short, it is one that takes a critical approach to the reading of the archive in order to lift the contradictory veil of silence that has enshrouded the experiences (and even the existences) of enslaved people and their descendants living around him. Whether or not it changes the record on Felsted's modern-day reception, it is not right that we continue to hail him as Jamaica's ‘first composer’ without acknowledging the contributions of his African-origin contemporaries. Be it in his conversation with the black coach driver and page who he chose to paint, in the labour of the enslaved woman he called Patience and bequeathed to his wife, or through his interactions with musicians such as George Liele and the singing black worshippers of the Kingston Parish Church organ gallery, Felsted's creative and social outputs were shaped by people of African origin. This is illustrated compellingly from his choice of biblical subject material for his second large-scale oratorio, The Dedication. As I have suggested, Felsted is likely to have composed this work in the 1790s in response to reports of the rising insurgency in Saint-Domingue.

The emerging picture of the real Felsted is, inevitably, an ambiguous one. He neither championed the chattel slavery system on which he and his society relied (as his newspaper criticism suggests), nor did he condemn it outright (as is clear from his slave ownership). What he did do, however, was sympathize with and comment on the suffering that he witnessed in the world around him. The point I want to emphasize at the end of this article is, needless to say, not a new one. We as scholars and performers of historical music today must choose carefully how we shape the musical legacy that is inherited by future generations. The relevance of Felsted's compositional output lies in the exploration and juxtaposition of both its overtly European elements and – although obscured by their fleetingness in the archive – its Afro-Jamaican contributions, which are no less relevant. As I hope to have demonstrated here, we surely need to scrutinize and re-evaluate colonial musicians like Samuel Felsted from multiple and diverse perspectives.