1. Introduction

Over the last decade there has been growing worldwide attention and momentum building around the issues of the empowerment and equality of women. Increasingly these issues are being considered both within society as a whole and more specifically within workplaces. Influential international organisations have made contributions to addressing and raising the profile of women's equality, including the World Health Organisation, the United Nations, the International Labour Organisation and the European Union, among many others who are also promoting these matters (WHO, 2009; UN, 2016; ILO, 2017a; EASHW, 2020). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which include gender equalityFootnote 1 (United Nations, 2016), along with the ‘me too’Footnote 2 campaign, have also made significant contributions to keeping gender in the spotlight, while the International Labour Organisation (ILO) has contributed to raising awareness of the gender labour gap (ILO, 2017a) and workplace gender diversity (ILO, 2017b). Collectively these initiatives have helped to provide a platform for more open debate surrounding gender diversity, equality and empowerment. However, there is still much global inequity regarding the treatment of, and behaviours and attitudes towards, women and there remains a long way to go to address this balance. The United Nations recently claimed that ‘Today not a single country has achieved gender equality’, citing barriers that include both law and culture (United Nations, 2019). There is an urgent need to harness the current focus on women's equality and build on the important momentum that has been gathering in this area.

The shipping industry has traditionally been male dominated, and it remains so, often perpetuated by masculine references surrounding the language used by the industry (Zhang and Zhao, Reference Zhang, Zhao, Kitada, Williams and Froholdt2015; Kitada et al., Reference Kitada, Pineiro and Mejia2019). Although there have been some advances over the last decade ( Tansey, Reference Tansey, Kitada, Williams and Froholdt2015; IMO, 2019), globally only about 2% of seafarers are women, and most serve on board cruise ships or passenger vessels (Ship Technology, 2017; IMO, 2019). Just one third of global shore-based maritime positions are filled by women. These figures perpetuate the difficulties of recruiting women into an industry that lacks female role models, especially in higher ranks (Kitada, Reference Kitada2013; Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie, Kitada, Williams and Froholdt2015). The industry is often seen as unattractive to women (IMO, 2019) and has been recognised as one in which the lived, workplace experiences of women often fall short of those of their male counterparts and can include prejudice, discrimination and harassment (Sampson, Reference Sampson2013; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Bloor and Little2013; Acejo and Abila, Reference Acejo and Abila2016). As Kitada and Langåker (Reference Kitada and Langåker2017) make clear, being part of a minority group can be challenging, both for the individual and for the wider industry.

Seafaring is also recognised as one of the world's oldest and most hazardous occupations. According to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), shipping is perhaps the most international of all the world's great industries – and one of the most dangerous (IMO, 2020). In addition to substantial risks to their safety, there is increasing recognition that seafarers also face higher risks to their mental (Carol-Dekker and Sultan, Reference Carol-Dekker and Sultan2016; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lee and Lee2017; Sliskovic, Reference Slišković and MacLachlan2017; Lefkowitz and Slade, Reference Lefkowitz and Slade2019) as well as physical health than those in the general working population.

Against this backdrop, the Gender Empowerment and Multicultural Crew (GEM) Project was an international study designed to consider seafarers’ welfare in relation to gender and multi-cultural crew environments across three countries – China, Nigeria and the UK (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016). This paper focuses on data, analysis and findings solely from the project's UK-based research and considers: (a) the gender-related experiences of women seafarers working in the UK shipping industry; and (b) the views of key industry stakeholders on how those experiences might be improved. It then reflects on the policy and practice implications of moving towards an industry that actively tries to understand and minimise gender inequality and its consequences for seafarers.

The gender-related experiences focused on, which were those the GEM Project's female seafarer participants most often reported, are now widely recognised as commonly experienced occupational safety and health (OSH) problems. In addition to isolation, which is increasingly experienced by both male and female seafarers [see, for example, Sampson and Ellis (Reference Sampson and Ellis2019)], these included harassment, sexual harassment and abuse which, as is discussed below, have very significant consequences for mental and physical health and wellbeing [see, for example, Women and Equalities Select Committee report (2018)], as well as for personal and wider safety (Swaen et al., Reference Swaen, van Amelsvoort, Bültmann, Slangen and Kant2004; van der Klauw et al., Reference van der Klauw, Hengel, Roozeboom, Koppes and Venema2016). They are defined as follows:

• Harassment is behaviour that makes someone feel intimidated or offended (Acas, Reference Acas2021).

• Sexual harassment occurs when an individual engages in unwanted behaviour of a sexual nature. Its purpose or effect is to: violate someone's dignity, creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the individual concerned. ‘Of a sexual nature’ can cover verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct including unwelcome sexual advances, inappropriate touching, forms of sexual assault, sexual jokes, displaying pornographic photographs or drawings, or sending emails with material of a sexual nature.

• Abuse is behaviour done to another person, without their full understanding or consent, which harms them in some way. This may consist of a single act or repeated acts.

The UK Merchant Navy has a long-established strongly hierarchical and patriarchal structure. In common with the wider and increasingly globalised maritime industry, it has seen significant changes in recent decades, particularly in relation to the increasing use of a range of fluid crewing strategies, with seafarers deployed to different ships on contracts of varying type and length. Both these contexts are of relevance to the findings presented below, and so are areas that will be returned to later in the paper. It is also important to note here, however, that another key change has been the increasing numbers of women in the UK industry. In 2019, 3⋅23% of seafarers (4⋅74% deck and 1⋅39% engine) were women (DoT, 2018). Furthermore, 10% of new SMarT (Support for Maritime Training) entrants in the UK in 2018/19 were female, up from 5% in 2017/18 (DoT, 2019). This all compares favourably with global figures.

In addition, the shipping industry is relatively highly regulated both nationally and, given its global nature, at the international level (Exarchopoulos et al., Reference Exarchopoulos, Zhang, Pryce-Roberts and Zhao2018). Key features of the regulatory context in terms of this paper include: the UK Equality Act, 2010, which prohibits discrimination and unwanted behaviour (including harassment) in the workplace, including that related to gender; and the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), 2006, which has been ratified in the UK and which establishes seafarers’ rights to decent working conditions. While the impact on the industry of the latter has been significant, there has been recognition that it could be amended to further enhance its role in addressing the maritime gender gap (Dragomir, Reference Dragomir2018; Pineiro and Kitada, Reference Pineiro and Kitada2020). Recent steps have been taken in this regard, in particular, for example, the 2019 amendments under which governments and shipowners are expected to adopt measures to better protect seafarers against shipboard harassment and bullying using guidance published jointly by the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) and the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). In addition, the International Safety Management (ISM) Code requires shipping companies to implement onboard safety management systems to protect seafarers. The ISM Code emphasises both the importance of seafarers’ participation in OSH management and the commitment of senior management to safety (Shan and Zhang, Reference Shan and Zhang2020). This reflects other international regulations, such as the European Working Time Directive (2003/88/EC), the European Framework Directive (89/391) and ILO Convention 155. Additionally, the importance of a participatory approach to OSH management arrangements is recognised, which should be developed and administered within the context of strong management commitment and management of regulatory oversight (Walters and Nichols, Reference Walters and Nichols2007, Reference Walters and Nichols2009).

Taken together, these employment rates and regulatory contexts suggest that the experiences of women seafarers working in the UK shipping industry considered in this paper are likely to be among the most positive of women seafarers globally.

2. Methods

The GEM Project, conducted between 2015 and 2016, was designed to consider seafarers’ welfare in relation to gender and multi-cultural crew environments. In order to reflect the global nature of the industry and the diverse experiences of seafarers working within it, the project focused on three countries, selected for their range of differences in maritime culture, population, economic status and attitudes to women working within the industry: China, Nigeria and the UK. The findings presented in this paper are drawn from the UK data; for the Nigerian findings see Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016) and for the Chinese findings see Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016) and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Zhao, Zhang, Wu, Pike and Broadhurst2017).

The GEM Project followed a mixed-methods approach, comprising a literature review, a questionnaire survey, a focus group, semi-structured interviews and panel discussions as part of a conference for industry stakeholders; for full details see Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016). The literature review allowed the identification of key areas in relation to the gender-related experiences of women seafarers and ways in which the participation and retention of women in the industry might be improved. From this, key questions were developed for measurement in the survey and subsequently explored in more depth in the focus group and the semi-structured interviews; with the collection of reaction to the findings, together with the identification of potential avenues for the development of policy and practice, taking place during the panel discussions.

2.1 Data collection

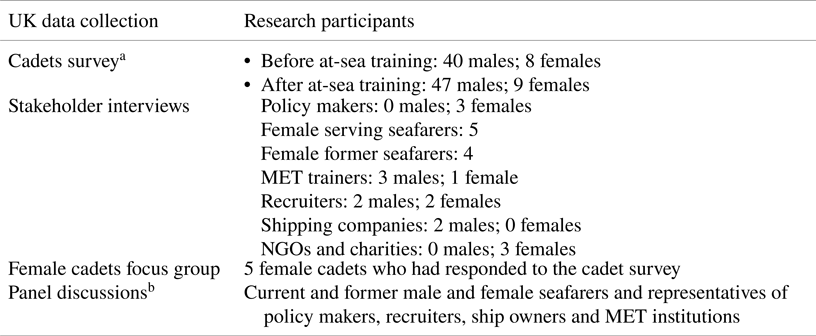

A paper-based self-complete questionnaire collected data anonymously from cadets at Warsash Maritime Academy in a classroom situation before and after their first phase sea training session. Following the ‘after’ survey, female respondents were invited to take part in a focus group to further explore the key issues identified in the survey. This took place in an informal setting and was recorded and transcribed. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with key stakeholders, including: policy makers, maritime education and training (MET) institution trainers, recruiters, shipping companies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and both current and former women seafarers. Most interviews were carried out by phone, though some were held face-to-face; all were recorded and transcribed. Lastly, at the GEM conference in 2016, public panel discussions were held with participants including: industry policy makers, educators, career developers, seafarers and maritime NGOs (see Table 1).

Table 1. Data collection and participants

Note.

a Numbers of respondents to the before and after first at-sea training surveys vary reflecting the cadets present when each survey was administered.

b The panel discussions were part of a public discussion forum held at the GEM Conference, ITF Seafarers’ Trust, London, June 2016.

All the research materials (questionnaires, focus group, interview and panel discussion guides, participant information sheets and consent forms) were developed in accordance with Solent University's ethical standards and approved by the University's Research Ethics Committee. As indicated above, the questionnaires were developed following an extensive literature review to identify key topics. They were finalised after piloting among representatives of the relevant participant groups. The focus group and interview guides were developed following the collection of the survey data and the panel discussion guide following the analysis of all the other primary data collected. All data collection methods used appropriate language and questions for the participants involved and took careful account of factors including gender and role. In addition to demographic and occupational data as appropriate, the topics covered included gender-related expectations ahead of first sea training, experiences during first sea training, experiences during a seafaring career, and factors influential over those experiences. Questionnaires were gender specificFootnote 3 and participants were able to self-identify their gender and complete the surveys they felt most appropriate to them.

A pragmatic approach was taken to sampling. All cadets in their first year at Warsash Maritime Academy in 2015 were invited to take part in the survey, and all the female cadets who completed the survey were invited to take part in the focus group. Response rates of the student cadets who were available during the survey time frame of two weeks was 86% responding to the survey and 71% to the focus group. Interviewees and panel discussion members were identified to represent key industry stakeholders and were approached directly.

The findings presented below draw primarily on the qualitative data set, which was coded and analysed thematically to consider the experiences of female seafarers and participants’ views on how such experiences might be improved. Supporting quantitative data, relevant to the themes considered, are used descriptively.

3. Results

The findings presented below first explore respondents’ perceptions of the experiences of women at sea; and second describe their views on how this experience might be improved.

3.1 What is the experience of women at sea?

Perhaps not surprisingly, it was clear from all of those who participated that the experiences of women at sea were mixed. Many spoke positively:

‘It felt like a family because [there were] only several of us on the ship. We were all very close to each other, just like a family…’ Female seafarer, interview 20

‘I had very positive experience on that ship. Many passengers were from Russia. I talked to them and we sometimes swap small gifts to each other.’ Female seafarer, interview 05

However, there were also substantial areas of concern that were specific to gender. These fell broadly into two groups: harassment (including sexual harassment, and physical and mental abuse) and isolation; both of which are considered in the following sub-sections.

3.1.1 Harassment and abuse

When asked before their first time at sea what they thought would be the biggest issue facing women on board, the cadet respondents in the study most commonly identified sexual harassment and abuse (19% N = 10), which included: anxiety of exploitation, rape, and concerns that some men would be under the impression that the women on board would be sexually interested in them. This was followed by sexism (12% N = 6), loneliness, isolation and segregation (8% N = 4); other issues included difficulties in gaining respect from fellow crew members, anxiety about sexist comments and inappropriate remarks, and being viewed as lacking in ability. When they returned from their sea time, sexual harassment had become a reality for some of the female seafarers, having been experienced five times (16% N = 8), with sexism experienced three times (9% N = 5). ‘Old school seafarers’ holding more traditional viewpoints, including negative stereotypes of women working on board, were reported twice (6% N = 3), as was gender discrimination (6% N = 3).

As a snapshot of the first-time experiences of a relatively small group of cadets, this level of harmful experience is particularly concerning. Even more worryingly, it clearly reflected the prevailing view among the industry stakeholder representatives, who identified the main issues that women face at sea as being: (1) sexual harassment and bullying, (2) job retention, and (3) discrimination. Respondents suggested that it was inevitable that women seafarers who remained and progressed in the profession as far as a senior officer rank, would have experienced some form of harassment or abuse during their career:

‘… a female Captain, she has had to go through cadet level up to Captain and she almost certainly at some point through her career would have had sexual harassment issues to deal with; however, she has dealt with them. I think it is inconceivable that she wouldn't have at some point.’ Male ship owner, interview 22

‘I would suspect if you asked any female cadet who've had some period at sea or close to their qualifying sea time, have they suffered some form of abuse harassment or bullying during their time at sea? The answer would be yes.’ Male ship owner, interview 21

‘I've met lots of young female seafarers who had said to me that the first issue was trying to get a particular colleague from a particular country to understand that “no” really does mean “no”, and when I am being nice to him I am not flirting with him and trying to get him to take me seriously as a professional and so on.’ Female recruiter, interview 19

‘If you're the only woman and if you're too friendly you're just after sex or whatever, or you're only there for one thing. If you're not friendly enough then you're a stuck up cow.’ Female seafarer, interview 12

As indicated above, the terms harassment and abuse cover a multitude of experiences, from illegal and violent behaviour through to inappropriate language. However, participants also recognised that considering whether or not to report such incidents of any type or severity was another difficulty that women working at sea routinely experienced. There was a clear view that reported cases likely represented just the tip of the iceberg, with under-reporting in part reflecting women fearing that incidents could be dismissed as ‘banter’:

‘Less easy to sort of illustrate or to explain to a captain, is what could be seen as joshing which perhaps takes a slight sexual connotation but not too much and then does the women just not have a sense of humour? At what point does she feel, now I need to complain? But now I shouldn't because this is not so bad … But now it is something else. And that sort of intermediate, grey area which I think a lot of women at sea do face and they don't know whether they should complain because then they are not one of the boys and then they are being a pain.’ Female policy maker, interview 3

‘ … so I got called up to the captain and he said, “Well I think you're making a mountain out of a molehill” [referring to the cook entering her cabin uninvited at night and a case of attempted sexual abuse] … I remember crying in my cabin thinking somebody, somebody come and rescue me but then a week or two later we're back in Sweden – the guy, the cook, had had a couple of drinks and he beat the mate up and he got the sack for that.’ Female seafarer, interview 12.

‘There is an awful lot of discrimination on board, sexism every day. If you don't respect your leader your base line is gone completely. I think that it comes down to company ownership and leadership as well. … As a cadet you can report, but if the person at the top is not strong enough to deal with it and isn't supporting those issues, then a lot of it will be silent and will [not be dealt with].’ Anonymised Conference Panel member

In practice, respondents indicated that the experience and expectation of abuse tended to lead to women trying to keep a low profile on board. One female cadet said she:

‘ ….. felt that I couldn't join in with the crew for fear of them being inappropriate.’ Female cadet, survey No. 3

This was perhaps exacerbated by the widely held view that women's behaviour on board would be judged very differently from men's:

‘… physical relationships between men and women on board is a thing that does happen … and it can damage the female's career, not greatly so for the men.’ Anonymised Conference Panel member

As a result, the experience of being a woman seafarer was recognised by many of the participants from across the industry as potentially lonely and isolating, which has serious implications for their occupational safety, mental health and wellbeing.

3.1.2 Isolation

Isolation is widely recognised as being a significant issue for seafarers generally (Sampson and Ellis, Reference Sampson and Ellis2019), but particularly for women, as well as other minority groups and younger people. Respondents recognised this and its impact on the retention of seafarers within the industry:

‘Isolation can drive people to leave. It is difficult, especially when you are young.’ Female policy maker, interview 1

This again was reflected in the views of the respondents who indicated that, over time, a seafarer's life has become less sociable.

‘I think all seafarers are vulnerable to isolation, the very unique conditions on board ships but being a woman on board, without necessarily having that support network there makes them more vulnerable to that issue.’ Female ex-seafarer, interview 9

‘I feel quite isolated a lot of the time.’ Female seafarer, interview 12.

Smaller crew sizes, increased bureaucracy and time-consuming paperwork, shorter port calls and multicultural crews leading to groups of those with a shared language, were identified as contributing to the potential for isolation (The Seafarer's Happiness Index, 2020). Additionally, lack of web-based connectivity or inconsistent or chargeable Wifi could compound the problem, particularly amongst younger crew who have grown up with this technology and are rarely without it onshore (Inmarsat, 2018).

Activities where crew can socialise together have arguably decreased since alcohol was banned onboard most vessels, with many seafarers choosing to relax alone in their cabins following their shift rather than meeting up socially (The Maritime Executive, 2020). Although living and working at sea means seafarers are in close proximity to other crew, the unique environment on board can be isolating for many:

‘If the norm on board the ship is for different crews just to go back to their cabins at the end of the day as soon as they have finished their shift … then I think Yes, there is a problem’. Female policy maker, interview 2

‘… the ship is an isolated workplace and it's not easy to supervise it – so it is very different from being an office, a factory, a workshop or whatever. It does make it a much harder work environment for women to operate in.’ Male ship owner, interview 21

Being in a minority group working at sea, such as being the only one of your gender or nationality, was recognised as having the potential to compound feelings of isolation:

‘… if you are one person from a certain culture and everybody is a different culture, there can be a sense of loneliness … she'd experienced the same thing but because of being a female, she was the only female on board and she experienced a sense of loneliness.’ Male MET representative, interview 14

‘… with multinational crews, the opportunity for social interaction is often, but not always, reduced. People don't speak the language of the others; they don't share the same interests and so you have increasing isolation.’ Male ship owner, interview 21

‘… there are relatively few female Asian seafarers in the first place in deck or officer positions and secondly those who are in those positions are more likely to go into the cruise sector where there are additional female seafarers on board, because they don't feel so isolated … From an individual level, European cultures, probably have less of a problem with that. You can't discount culture in this process – it isn't just about gender.’ Male ship owner, interview 22

3.2 What do participants think will improve the experience of women at sea?

The need for consistent and high standards of education, training and mentoring were identified by respondents as being key to improving the experiences of women working at sea. The importance of incorporating wellbeing and diversity into training was also identified as key both to preparing cadets for embarking on their first sea time and to equip senior management to deal with issues such as harassment, abuse or isolation should they arise on board. This is consistent with recent work by Pineiro and Kitada (Reference Pineiro and Kitada2020), who noted that seafarers’ training tends to be focused around technical skills and far less on the non-technical aspects of seafaring, such as leadership and management. Similarly, there was a widely held view that providing experienced mentors for cadets and new crew had the potential to be effective, recognising that a shift towards making the duty of care the predominant on board culture would significantly contribute to enabling young crew, particularly those in minority groups, to work in a safe and supportive environment:

‘It all comes down to tolerance on board and as a culture. You can't influence a culture in the short term, but you can influence the climate and I think the climate that the ship owners are setting needs to be of zero tolerance and enforced support structures in place on board vessels whereby the lines of communication for certain comeback.’ Interview 17 female recruiter

The conference panel discussion noted that some shipping companies have introduced training schemes covering these areas:

‘Not only gender, but diversity and multi-cultural issues … preparing their workers to work in a multi-cultural environment … This kind of training has to be repeated from time to time to remind them [the seafarers] that these are the policies of the company and this is the code of conduct that this company is asking you to follow and if you misbehave this is the consequences, it has to be clear.’ Anonymised conference panel member

However, respondents felt that such arrangements were unusual and that, more generally, appropriate training and mentoring arrangements were lacking.

4. Discussion

The findings present a concerning picture of the experience of women working at sea. Cadets about to embark on their first sea training identified sexual harassment and abuse as the biggest issues they expected women working at sea to face. On their return from that first sea training, approximately one in six reported experiencing (or witnessing the experience of) sexual harassment. This is consistent with earlier findings, which suggest that sexual harassment of female seafarers by male crew is commonplace (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Bloor and Little2013) and indicates worryingly little progress over time. Relatedly, and of even more concern, representatives of stakeholders from across the industry indicated that this was the norm and it was the widely held view that all women who remained and progressed in the industry would have experienced sexual harassment at least once in their working lives.

In addition, some respondents spoke in ways that reflected unconscious bias, for example, by suggesting that certain job types, industry sub-sectors and so on, were more appropriate than others for women to work in, and implying that pastoral and duty of care obligations in relation to female, as opposed to male, staff would be different and could make additional and burdensome requirements on senior staff. Furthermore, these findings, in common with those from other industries (Berdahl and Moore, Reference Berdahl and Moore2006; EU, 2018; TUC, 2019; Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2020) suggest that the experience of harassment and abuse was common not only among women and other minorities on board, but also among lower ranked and younger crew members generally (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016). This, of course, is bound to contribute to concerns about reporting, evident in the data, particularly where senior crew members are the perpetrators.

Studies from outside the shipping industry suggest that anywhere from around 25% to over 80% of women experience sexual harassment in their lifetimes (Feldblum and Lipnic, Reference Feldblum and Lipnic2016). In a recent UK study, over half of women respondents reported experiencing sexual harassment at work, with half of those women saying that they had been subjected to unwelcome sexual jokes in the workplace more than six times in their lives (TUC, 2016). These findings come from a relatively small sample, but they suggest rates are likely to be even higher among women working at sea. This is concerning given the well-recognised consequences of the experience of sexual harassment. As the recent Women and Equalities Select Committee report (2018) states:

Sexual harassment can have a devastating impact on those who are subjected to it. Mental and physical health often suffer, leading to anxiety, poor sleep, depression, loss of appetite, headaches, exhaustion or nausea. Victims feel humiliation, mistrust, anger, fear and sadness.

The experience of isolation when working at sea was also regarded by the respondents as commonplace, particularly among women and other minority groups. This was, in some instances, related to the experience of harassment or abuse. Participants indicated that women who had experienced harassment or abuse sometimes withdrew, as far as possible, from on board life outside work as a means of self-protection. This is consistent with earlier findings suggesting that, in this male-dominated culture, female seafarers frequently manage their identity in ways that prioritise work over their individual needs (Kitada, Reference Kitada2010).

In addition to the occupational health and wellbeing consequences of such experiences to women seafarers themselves, the potential implications for their physical safety, and more widely the safe operation of the vessel, and therefore the safety of the crew, cargo and environment, are particularly worrying. For example, research from the construction sector, a similarly male-dominated industry with relatively high levels of physical risk, indicates that workers who reported the experience of violence and harassment by colleagues more frequently reported involvement in an occupational accident than those without such experience (van der Klauw et al., Reference van der Klauw, Hengel, Roozeboom, Koppes and Venema2016). This is consistent with earlier research identifying psychosocial work characteristics as risk factors for workplace accidents (see, for example, Swaen et al., Reference Swaen, van Amelsvoort, Bültmann, Slangen and Kant2004), and suggests that seafarers experiencing harassment are likely to be at greater risk of physical accident, perhaps as a result of the impact on both their personal mental and physical health and wellbeing and the dynamics of the workplace in which such harassment occurs.

As outlined in the Introduction, seafaring is a unique working environment, and there are several inherent factors that provide context to the onboard experience of seafarers reported by the participants in this study, in particular: the hierarchical structure of the Merchant Navy and the ways in which seafarers are deployed within the industry.

4.1 Hierarchy

The Merchant Navy, much like the Royal Navy or other defence navies across the world, has a steep hierarchical structure that provides a command and control system where the captain's word is historically not questioned. Together with a long tradition of a strong patriarchal structure, this inevitably enables an arena in which bias and stereotyping can flourish, albeit not necessarily with any conscious intent.

On board, the hierarchical rank system means that senior officers, particularly the captain, are the primary influence in establishing the onboard culture determining which behaviours are acceptable and which are not. These officers, therefore, are in a position to instil a culture of tolerance and respect on board and so contribute to the development of a more inclusive and accepting work environment. As indicated above, respondents to this study clearly recognised this potential, just as they did the current widespread failure to exploit it within the industry. So, when asked about ways in which the experience of women working at sea might be improved, training, in relation to leadership skills, was commonly identified.

4.2 Crewing strategies

Much of the Merchant Navy operates by deploying seafarers to a different ship for each voyage, as well as staggering crew changes and issuing contracts of different lengths and types (such as permanent or for a single voyage) to seafarers of different ranks or nationalities. As a result, seafarers are frequently working on unfamiliar vessels and with unfamiliar colleagues, who may change during their time on board. While this approach to crewing may mean that an abusive colleague leaves the ship, so providing relief for the remainder of a seafarer's tour, it also has the potential to contribute to experiences of isolation and loneliness and is unlikely to lead to a workplace environment in which women, particularly those in more junior roles, would feel confident of support when reporting the experience of abuse. This approach to crewing is a reflection of the wider industry focus on efficiency and value for money, which has led to relentless pressure to reduce crewing costs and has very substantial implications for seafarers’ occupational health, safety and wellbeing (Walters and Bailey, Reference Walters and Bailey2013). In contrast, a recent study indicated that stable crewing strategies, in particular where the top fourFootnote 4 senior officers are kept in place for more than one voyage, provide an environment engendering diversity and supporting a strong onboard safety culture (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Butt, Neale, Wincott and Passman2019b). This highlights the central role of shipping companies and shore-side management in the way in which seafarers are trained and deployed, expectations of on board culture, and commitment to the provision of a safe and supportive work environment in which seafarers or their representatives are able to participate in the development of the arrangements made to manage their occupational health, safety and wellbeing. Ultimately, these organisations can introduce the changes needed to improve the experiences of women, and indeed all those working at sea. As one of the participants put it:

‘… a lot of seafarers blame people ashore who have never been to sea for not understanding them and therefore communicating poorly with them because they don't know what life at sea is like. But by the same token we hear just as many complaints about, for example, Superintendents ashore who have been to sea having poor management skills and therefore sort of a militaristic approach to management which they take from sea to shore with them and then impose back upon the ship they are dealing with now that they are ashore, having just as deleterious an impact on the seafarer as the communication style of those who were ashore who've never been to sea.’ Interview 19, male recruiter

This also means that, although leaders still have an important role on board, they are less likely to be invested if there is a constant fluidity of crew and officers (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Honebon and Harland2019a). The implication is that training is required at sea and ashore to provide leadership skills to ensure that pastoral care is adequately provided to all seafarers, and crewing policy changes may have a role to play in creating an appropriate culture and environment.

In addition to changes on board achieved through developments in shore-side management policy, progress requires strategic and policy development at the industry level. Some indications of progress include the guidance on addressing bullying and harassment published jointly by the Maritime UK's Women in Maritime Taskforce initiative ‘to improve the gender balance at all levels in the maritime industry both at sea and on shore’ (DoT, 2019). However, as yet there is little to no sense of the urgency or reach and depth of change that will be required for wholesale reform.

There was widespread agreement amongst the participants that training, particularly in leadership skills and mentoring, were key to improving the experiences of women working at sea. While they were able to point to some instances of progress in these areas, generally the respondents indicated that such schemes were sorely lacking. This was exacerbated by an impression that, to some extent, senior officers may mimic the behaviours they experienced as junior seafarers, so perpetuating poor behaviour across the industry – a trait that has been recognised in other sectors (Zellars et al., Reference Zellars, Tepper and Duffy2002). The underlying assumption among some employers is that women seafarers tend not to remain in the industry as long as men and are more costly, and therefore are a poorer investment than their male counterparts. Despite evidence to the contrary (Thomas, Reference Thomas2004), these beliefs persist and perpetuate both low recruitment rates and the failure to make progress in improving the experiences of women seafarers.

This research had limitations. Despite representing most of a cohort of new cadets at a major UK maritime academy, the absolute sample size of the survey was small. Additionally, in common with all research, across the range of methods used the study is likely to have captured only the views of those with an interest in the areas being studied. Nevertheless, the work represents one of the first attempts to directly address gender equality and the experiences of women seafarers both with seafarers themselves and with representatives from across the industry. The extent of consensus among the participants, together with the widespread recognition of stakeholders from across the sector of the experiences of serving women seafarers captured by the project, suggest that the findings reflect prevailing industry conditions. Nevertheless, further examination of the issues raised, with larger and potentially more representative samples, is still needed, in particular to more fully understand the sectoral and workplace contexts in which the kinds of experiences reported by the participants occur and so how policy and strategic changes might improve such experiences.

5. Conclusions

These findings suggest that female seafarers are likely to be at even greater risk than their male counterparts because of their higher likelihood of encountering sexual harassment on board. The data demonstrate an expectation of sexual harassment as normalised behaviour on board and, in this regard, the findings make it clear that there is a long way to go to before the industry is anywhere near gender equality. In addition, working under stress and enduring harassment in any work setting has wider safety implications (van der Klauw et al., Reference van der Klauw, Hengel, Roozeboom, Koppes and Venema2016). In the case of seafaring, these extend to other seafarers, as well as to the vessel, its cargo and the environment.

The data in this study relate to the maritime industry in the UK and are likely to represent generally more positive experiences than those faced by women seafarers elsewhere in the world (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Broadhurst, Zhao, Zhang, Kuje and Oluoha2016). As ITF points out, in some countries MET institutions are not allowed to recruit and train women to nautical courses. Where they can train, women seafarers can be subject to discrimination and harassment, may face prejudice from ship owners who do not employ women, can face lower pay for work that is equivalent to that of their male colleagues, and are sometimes denied the facilities or equipment available to male workers (ITF, 2020).

Global momentum has opened up debate surrounding gender and it is crucial that opportunities arising from this new visibility are not lost and that policy makers focus on ensuring that the maritime industry takes urgent steps to improve the work experiences of minority seafarers. While it is vital to ensure that technical skills are kept up to date as new technologies advance and working practices evolve, balancing technical with non-technical training is vital. This should include the teaching of leadership and soft skills to ensure that seafarers are better equipped to function in a fast-changing industry. Key to this is training at all levels, from cadets to senior officers, and the maritime syllabus must be updated and revised accordingly.

There is increasing recognition across the industry of the urgent need to address the risks that seafarers face to their physical and mental health on a daily basis, and so reduce the very large number of preventable work-related seafarer deaths and illnesses globally. Recent work, for example, Lefkowitz and Slade (Reference Lefkowitz and Slade2019) and Sampson and Ellis (Reference Sampson and Ellis2019), identifies both seafarers’ work and employment conditions, and their training, as key areas in which changes to support improved mental health, wellbeing and safety must be made. The findings in this paper relating to the experiences of women seafarers support these conclusions and suggest that such changes have the potential to improve the experiences of all those working at sea, particularly those minorities currently enduring the poorest workplace experiences. As one of the female policy participants said:

‘If you want people to come back for a second tour of duty and you want them to see it as a career for life, then you have to make it an environment where they want to work. And it's not just men, it's women as well. The way that you need to do things to make it attractive to women are also required to encourage men to stay on board. … What we would accept 50 years ago isn't the case anymore and you have to create an environment that everybody would want to work in.’

Achieving this requires wholesale commitment, buy-in and substantial investment from employers, as well as policymakers, across the industry; but crucially it cannot be realised without actively listening to and acting on the views of seafarers themselves and their representatives. In short, what is needed now is a sea change.

Funding

This work was supported by ITF Seafarers' Trust [grant reference 1073].

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the project sponsor, The ITF Seafarers' Trust, UK and all the maritime stakeholders who kindly gave their time to participate in the research. We would also like to thank Katie Stickland from Solent University for her endless support with this paper. Grateful thanks also to Dr Amos Kuje, Assistant Director of the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency and Nancy Obluoha from the Nigerian National Maritime Academy for their help on the wider project from the Nigerian perspective.