Breast-feeding, and in particular exclusive breast-feeding as defined in Table 1, provides optimal infant nutrition(1–3). Human milk contains numerous immunological components that directly protect infants. Studies have shown that exclusive breast-feeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in the respiratory, gastrointestinal and urinary tracts(Reference Stuebe and Schwarz4–Reference Chantry, Howard and Auinger8), and that it protects premature children from neonatal sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis(Reference Rønnestad, Abrahamsen and Medbø9–Reference Quigley, Henderson and Anthony11). In addition, the immunological components of human milk support the development and maturation of the infant’s own immune system, which may explain some of the long-term health benefits observed in breast-fed children(12). Recent studies have also indicated long-term health benefits of lactation for the mother, such as a reduced risk of breast cancer(1, Reference Gartner, Morton and Lawrence2).

ORS, oral rehydration salt.

*Partial breast-feeding is similar to ‘complementary feeding’ in the WHO document(54).

Breast-feeding is influenced by a variety of factors. These include sociodemographic, biomedical, health service-related, psychosocial and cultural factors, as well as public breast-feeding policy(Reference Yngve and Sjöström13, Reference Rogers, Emmett and Golding14). The factors associated with cessation of any breast-feeding are well documented(Reference Rogers, Emmett and Golding14–Reference Scott and Binns16), while less is known about the factors associated with the cessation of exclusive breast-feeding and full breast-feeding. Fully breast-fed infants are defined as those who are either exclusively breast-fed or who receive water-based supplementation, but no solid food or formula (Table 1). Current WHO recommendations(3) highlight the desirability of 6 months of exclusive breast-feeding. This necessitates studies of the factors associated with the cessation of exclusive or full breast-feeding.

The Norwegian health authorities recommend exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life, echoing the WHO recommendation(3, 17). Almost all mothers in Norway initiate breast-feeding (98 %)(18). Some 80 % still breast-feed at 6 months, but only 9 % do so exclusively. The largest decrease in exclusive breast-feeding, from 63 % to 46 %, occurs between 3 and 4 months(18).

Early supplementation with infant formula, water or water-based supplements like sugar water is associated with a shorter duration of exclusive or full breast-feeding(Reference Chantry, Howard and Auinger8, Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich19–Reference Alikasifoglu, Erginoz and Gur23). However, supplementation with water or sugar water has been studied less than formula supplementation(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich19, Reference Martin-Calama, Bunuel and Valero20, Reference Perez-Escamilla, Segura-Millan and Canahuati22). Knowledge about the possible influence of other health service-related factors is limited. Few studies have reported associations between the duration of exclusive or full breast-feeding and breast-feeding problems, transfer to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or the size of the birth institution(Reference Cernadas, Noceda and Barrera24–Reference Scott, Binns and Oddy27). In addition, studies investigating the association between delivery by Caesarean section (CS) and cessation of exclusive or full breast-feeding have also been inconclusive(Reference Alikasifoglu, Erginoz and Gur23, Reference Cernadas, Noceda and Barrera24, Reference Cattaneo and Buzzetti28).

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined the association between these health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding among mothers who are still breast-feeding. Moreover, many previous studies have ignored the fact that these associations may differ at different points in time during the first 6 months after birth. The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), a large, prospective pregnancy cohort, enables examination of both issues.

The objectives of the present study were: (i) to describe the prevalence of full and partial breast-feeding during the first 6 months in mothers participating in MoBa; and (ii) to study the associations between health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding among mothers still breast-feeding at three different time intervals during the first 6 months.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample

The data set is part of the MoBa cohort, initiated and maintained by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. In brief, MoBa is a pregnancy cohort that in the years from 1999 to 2008 has included ∼107 000 pregnancies. Women were recruited to the study through a postal invitation in connection with a routine ultrasound examination offered to all pregnant women in Norway during weeks 17–18 of gestation. The participation rate was 43 %(Reference Magnus, Irgens and Haug29). Three questionnaires (Q1–Q3) were completed during pregnancy, and the first questionnaire after birth (Q4) was completed at 6 months. The respective response rates for questionnaires Q1–Q4 were 95 %, 93 %, 92 % and 97 %. The self-completed questionnaires covered health, chemical and physical factors in the environment, nutrition, lifestyle and background factors(Reference Magnus, Irgens and Haug29) (the questionnaires may be downloaded from http://www.fhi.no). The cohort database is linked to the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN)(Reference Irgens30). The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical Research and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate(Reference Magnus, Irgens and Haug29).

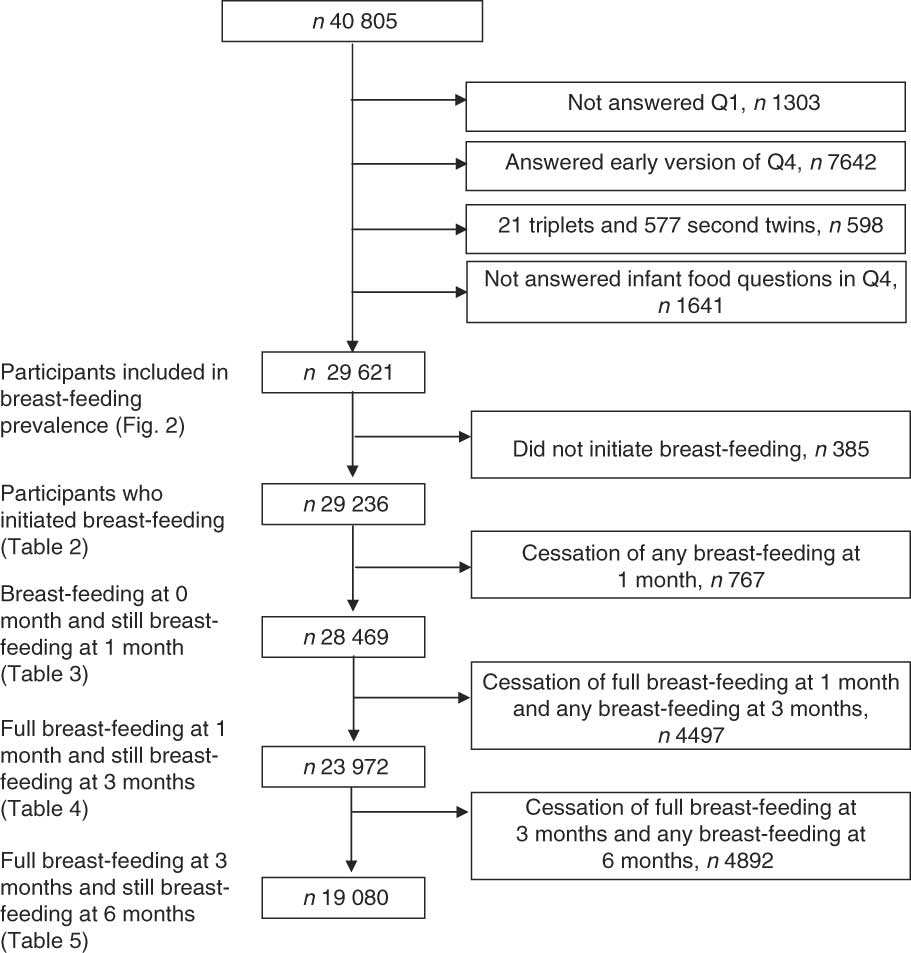

At the time of the present analysis, Q4 was available for 40 805 mother–infant pairs (taken from the quality-assured data file (version 3) made available for research in 2007). Our study sample included all participants who had answered both Q1 and version b of Q4. The infants were born during the period 2002–2005. Triplets and second twins were excluded. Pairs of twins were represented by twin 1. There was no difference in breast-feeding prevalence between twin 1 and twin 2 during the first 6 months (all P > 0·05). Mothers who did not answer all questions about infant nutrition (questions 15–18 in Q4) were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 29 621 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram for inclusion of participants for the study from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort

Variables

The breast-feeding data are based on three questions about infant nutrition in Q4. The questions were asked retrospectively 6 months after birth. The first question asked about infant feeding during the first week after birth and offered the following alternatives: ‘breast milk’, ‘water’, ‘sugar water’, ‘infant formula’, ‘other’ and ‘don’t know’. The second question was: ‘What kind of milk did your baby receive at months 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6?’ The possible answers were: ‘breast milk’, ‘formula’ and ‘other milk’. For both of these questions more than one liquid could be marked. The last question was: ‘In which month did you start giving complementary food to the child?’ The answers to this final question covered seventeen different food items, which were collapsed into one complementary food variable.

The breast-feeding categories used in the present study were based on WHO definitions (Table 1). The category ‘exclusive breast-feeding’ could only be studied the first week of life, as the use of water, water-based drinks and fruit juice in the period 0–5 months was not included in all versions of the questionnaire. The ‘full breast-feeding’ variable used in the regression analysis describes infant feeding ‘since birth’, except for supplementation during the first week of life. In the present article, ‘breast-feeding’ must be understood as ‘breast milk feeding’, as no data were available on the feeding practice.

The following health service-related factors were investigated: (i) use of supplementation during the first week of life; (ii) CS delivery; (iii) breast-feeding problems; (iv) transfer to NICU; and (v) size of birth institution. Data about the use of supplements during the first week of life and breast-feeding problems are derived from Q4. Information on CS delivery, transfer to NICU and size of birth institution are taken from the MBRN. Breast-feeding problems for which health personnel were contacted during the first month after birth were combined into a dichotomous variable, which was coded as ‘no’ if there were no problems and ‘yes’ if the mother reported (i) mastitis, (ii) sore nipples or (iii) other undefined breast-feeding problems. The breast-feeding problems were of such severity that health personnel were contacted during the first month after birth. Supplementation during the first week of life was classified into four categories: ‘only breast milk’, ‘breast milk and water’, ‘breast milk and sugar water’ and ‘breast milk and infant formula’. Five categories were offered for size of institution (number of births per year): <500, 500–1499, 1500–2999, >3000 and unknown. Three categories were offered for transfer to NICU: ‘no’, ‘yes’ and ‘unknown’, while delivery method was assessed by reference to a dichotomous variable: ‘vaginal’ or ‘Caesarean section’.

Pre-pregnancy BMI and smoking status were derived from Q1, administered in weeks 17–18 of gestation. Educational level, household income, smoking status during lactation and marital status were derived from Q4. Birth year, sex and birth weight of the infant, plurality, maternal age, parity and place of residence were obtained from the MBRN(Reference Irgens30). Birth-weight data not available from the MBRN (n 72) were calculated using data taken from maternal reports in Q4. We used data on smoking during pregnancy in the analysis of full breast-feeding cessation during the first two time intervals, and for the full breast-feeding cessation between 3 and 6 months we used smoking data from Q4.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s χ 2 test was used to test for differences between proportions. Multivariable Poisson regression with robust variance estimates was used to calculate relative risk (RR) with 95 % confidence interval for cessation of full breast-feeding, at the different time intervals and for all health service-related factors, with and without adjustment for maternal age, maternal education, smoking, marital status, region of birth, household income, birth year, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, sex of the infant, birth weight and plurality.

We first examined the associations between the selected health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding, for each month. Due to the similarity of the findings for months 1 to 6 (data not shown), only three outcomes were selected: cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month, cessation in the time interval between months 1 and 3, and cessation in the time interval between months 3 and 6. Only mothers fully breast-feeding at month 1 were included in the second regression analysis (Table 4), and only the mothers fully breast-feeding at month 3 were included in the third regression analysis (Table 5). The criteria for inclusion in the groups are shown in Fig. 1.

All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Poisson regression was analysed using the STATA statistical software package version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participants who were excluded for not having answered the infant feeding questions (n 1641) did not differ from the other participants with regard to maternal characteristics, but were more likely to be smokers (P = 0·019).

The prevalence of full breast-feeding during the first week was 81·7 % (n 24 210). The proportion of those exclusively breast-feeding was 70·5 % (n 20·872), while 11·3 % (n 3338) were predominantly breast-feeding. Among those who did not fully breast-feed, 17·0 % (n 5026) were partially breast-feeding and 1·3 % (n 385) were not breast-feeding at all.

The women who did not initiate breast-feeding (n 385) exhibited lower educational level, higher pre-pregnancy BMI, greater incidence of smoking, greater number of CS deliveries, greater number of twin births and lower infant birth weights than the women who initiated breast-feeding. No differences were found with regard to maternal age, household income, parity and infant gender (Table 2).

Table 2 Sample characteristics of mothers by reference to breast-feeding initiation in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

*P value calculated using Pearson’s χ 2 test.

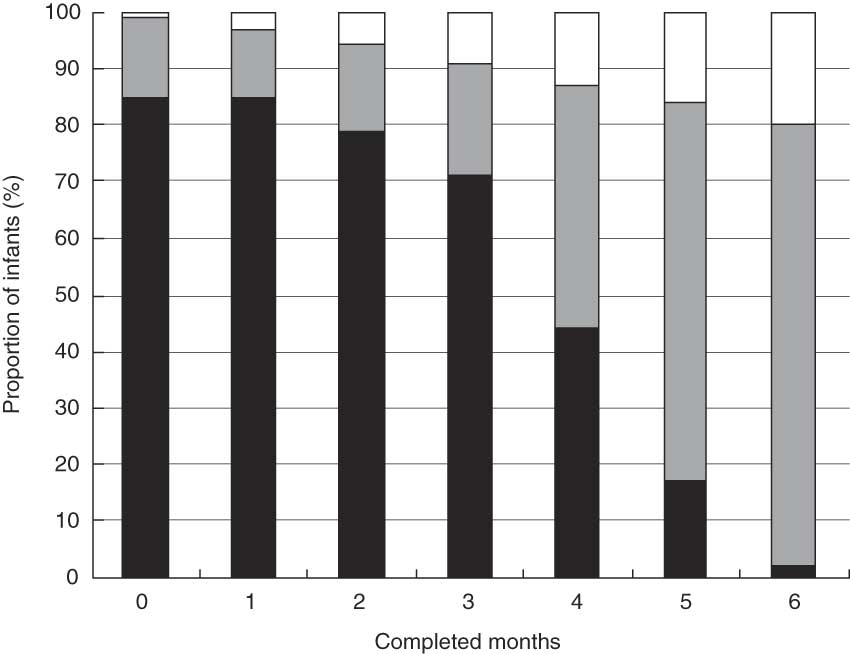

While 80·0 % of the children were breast-fed at 6 months, only 2·1 % were fully breast-fed at this point in time. There was a pronounced decline in full breast-feeding starting from 3 months, with a 26·9 % decline (from 70·9 % to 44·0 %) between 3 and 4 months and a further 27·3 % decline (from 44·0 % to 16·7 %) between 4 and 5 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Prevalence of full (▪), partial (![]() ) and no breast-feeding (□) during the 6 months after birth for 29 621 women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

) and no breast-feeding (□) during the 6 months after birth for 29 621 women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

An increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month of life was associated with supplementation with water, sugar water or formula during the first week of life, CS delivery and breast-feeding problems, but not institution size. Transfer to NICU was associated with a lower risk. Supplementation with formula was associated with a sixfold risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month (RR 5·99; 95 % CI 5·58, 6·42; Table 3).

Table 3 Health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding in mothers still breast-feeding during the first month after birth (total n 28 469), Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

RR, relative risk; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

*Adjusted for the other variables in the table and maternal age, maternal education, smoking during pregnancy, marital status, region of birth, household income, birth year, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, sex of the infant, birth weight and plurality.

†Sugar water could include water.

‡Formula-fed could include sugar and/or water.

§Including 207 births outside institution.

CS delivery and supplementation with water, sugar water or formula during the first week of life were still associated with an increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding in the time interval between months 1 to 3. The greatest risk was associated with supplementation with sugar water during the first week of life (RR 1·48; 95 % CI 1·34, 1·64; Table 4).

Table 4 Health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding in mothers still breast-feeding between 1 and 3 months after birth (total n 23 972), Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

RR, relative risk; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

*Adjusted for the other variables in the table and maternal age, maternal education, smoking during pregnancy, marital status, region of birth, household income, birth year, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, sex of the infant, birth weight and plurality.

†Sugar water could include water.

‡Formula-fed could include sugar and/or water.

§Including 207 births outside institution.

Supplementation with water or sugar water during the first week was still associated with the risk of cessation of full breast-feeding in the time interval between months 3 to 6 (RR 1·02; 95 % CI 1·01, 1·02; Table 5).

Table 5 Health service-related factors and cessation of full breast-feeding in mothers still breast-feeding between 3 and 6 months after birth (total n 19 080), Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 2002–2005

RR, relative risk; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

*Adjusted for the other variables in the table and maternal age, maternal education, smoking during pregnancy, marital status, region of birth, household income, birth year, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, sex of the infant, birth weight and plurality.

†Sugar water could include water.

‡Formula-fed could include sugar and/or water.

§Including 207 births outside institution.

Discussion

The key finding of the present study is the association between supplementary feeding with formula, water or sugar water during the first week of life and the increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding, not only during the first month but also in months 1 to 3 of life.

The main strengths of the study include the large sample size and the link to the MBRN. Participants were recruited from both urban and rural regions, and represented all age and socio-economic groups. Further, the study enables the investigation of important factors associated with the cessation of full breast-feeding, as well as adjustment for various confounders. In contrast to most other studies of cessation of full breast-feeding, we studied health service-related factors by reference to mothers who were still breast-feeding. Moreover, our examination of the associations of these factors for different time intervals after birth differs from most other studies, which presented hazard ratios during the first 6 months. Proportionality of hazards during the whole period of observation is a necessary assumption for such analyses, which was not the case in the present study. In addition, the use of risk ratios facilitates better interpretation of the results and avoids overestimation of the risk when events are common, which might be the case when logistic regression is used and when results are presented as odds ratios(Reference Bland and Altman31).

A limitation of the present study was the retrospective approach, which implied a 6-month recall of infant nutrition. The long recall period may have caused overestimation of the duration of full breast-feeding(Reference Bland, Rollins and Solarsh32). However, Merten et al. reported no differences in the proportion of fully breast-fed infants when comparing 24 h recall and retrospective data(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich19). Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured confounders may have influenced the associations.

The participation rate in MoBa is only 43 %(Reference Magnus, Irgens and Haug29). The potential bias due to self-selection in MoBa was recently evaluated by Nilsen et al.(Reference Nilsen, Vollset and Gjessing33); no statistically relative differences in association measures were found between participants and the total population regarding eight exposure–outcome associations evaluated.

The primary aim of the present study was to describe breast-feeding prevalence in the MoBa cohort. The findings regarding initiation of breast-feeding and breast-feeding prevalence closely mirror the findings made in the representative Norwegian Infant Nutrition Survey (SPEDKOST) of children born in 1998(Reference Lande, Andersen and Baerug34).

SPEDKOST (n 2383) also employed retrospective questionnaires administered 6 months after birth to collect data on infant nutrition. However, it reported on ‘exclusive breast-feeding’, which was defined as including water and thus differs slightly from ‘full breast-feeding’ as used in the present study. In SPEDKOST, the prevalence of full breast-feeding was only 1–2 % higher than that of exclusive breast-feeding (B Lande, personal communication). Accordingly, the data on exclusive and full breast-feeding in the two studies can be compared, even if the terms have been defined slightly differently. The only material difference in breast-feeding prevalence between SPEDKOST and MoBa can be observed at 6 months: SPEDKOST shows 7 % exclusive breast-feeding while MoBa shows only 2·1 % full breast-feeding. The lower prevalence at 6 months observed in MoBa may be explained by differences in the questions asked about infant feeding at that point in time.

We observed a large decline in the incidence of full breast-feeding starting at 3 months (Fig. 2). One possible explanation could be that the traditional practice of introducing solid food between months 4 and 6 is still in use. The Norwegian health authorities amended its infant feeding advice in 2001, and have since then recommended exclusively breast-feeding during the first 6 months.

The breast-feeding initiation rate of 98·7 % is higher than in most industrial countries, but comparable to other Nordic countries, some European countries and Australia. The proportion of any breast-feeding at 6 months (80·0 %) is among the highest in Europe and the industrialized world(Reference Callen and Pinelli35, Reference Cattaneo, Yngve and Koletzko36). The proportion of fully breast-fed infants at 4 months (44·0 %) equals the European average, while a rate of 2·1 % for fully breast-fed at 6 months seems low compared with other European countries(Reference Cattaneo, Yngve and Koletzko36). However, differences in data collection, breast-feeding definitions and participant selection make comparison difficult.

Supplementary feeding with water, sugar water or formula during the first week of life was associated with an increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month. A sixfold higher risk was observed where the infant received formula (Table 3). A representative survey from the USA reported a strong association between supplementation (formula or/and water) in the maternity unit and not being exclusively breast-fed at week 1(Reference Declercq, Labbok and Sakala37). Moreover, several studies have linked the use of formula during the first week to shorter overall duration of exclusive or full breast-feeding(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich19, Reference Alikasifoglu, Erginoz and Gur23, Reference Riva, Banderali and Agostoni38, Reference Ekström, Widström and Nissen39).

Perez-Escamilla et al. identified an association between shorter duration of exclusive breast-feeding and pre-lacteal feeds with water but not feeds with water-based liquids such as tea, juice or sugar water(Reference Perez-Escamilla, Segura-Millan and Canahuati22). On the other hand, Nylander et al. identified links between supplementation with sugar water and a shorter duration of exclusive breast-feeding(Reference Nylander, Lindemann and Helsing40), where exclusive breast-feeding was defined as in Table 1 (G Nylander, personal communication). In our study we also found an association between supplementation with formula, water or sugar water during the first week and cessation of full breast-feeding between 1 and 3 months (Table 4). This suggests a late effect on cessation of full breast-feeding of supplementation during the first week. To the best of our knowledge, such late associations have not been described previously. In a Spanish study, no differences were found regarding the introduction of formula at 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks when a group receiving sugar water as a supplement was compared with a control group receiving no supplementation(Reference Martin-Calama, Bunuel and Valero20).

The associations between cessation of full breast-feeding and supplementation with water or sugar water remained statistically significant in the time interval 3–6 months, but were very weak and thus of no clinical relevance (Table 5).

One feasible explanation for the associations between supplementation during the first week of life and cessation of full breast-feeding reported here is that supplementation during the first week is an indicator of delayed lactogenesis or problems with the initiation of breast-feeding not reported or included in our category of breast-feeding problems. Alternatively, supplementation during the first week may disturb the normal lactation physiology, and lead to reduced milk production and cessation of full breast-feeding. The associations may also be explained by unknown factors.

In the present study we did not obtain any information about the amount of formula administered, any reason why supplement was given or the frequency of its use. It has been reported that the increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding associated with formula supplementation can be modified by altering the frequency of supplementation(Reference Howard, Howard and Lanphear21). Supplementation with infant formula may also occur when maternal motivation to breast-feed exclusively is lacking.

Avoidance of supplementation without medical indication is one step in the WHO/UNICEF ten steps for a Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI)(41). This is an important tool for reducing unnecessary supplementation by promoting early breast-feeding, feeding on demand, rooming-in and avoiding the use of a pacifier(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich19, Reference Declercq, Labbok and Sakala37, Reference Giovannini, Riva and Banderali42, Reference Merten and Ackermann-Liebrich43). Today, the majority of infants born in Norway are born in a BFHI-designated hospital. Nevertheless, 29·5 % of the infants in our study were not exclusively breast-fed during the first week of life. However, this figure is low compared with other European countries and the USA, where 63–70 % of infants receive supplements in the maternity units(Reference Declercq, Labbok and Sakala37, Reference Riva, Banderali and Agostoni38, Reference Merten and Ackermann-Liebrich43).

The question arises whether there are medical reasons for introducing supplements to nearly one-third of the infants in our study sample. Supplementation for medical reasons has been reported to have no influence on duration of exclusive breast-feeding(Reference Ekström, Widström and Nissen39), although non-medical reasons are reported to be the most common cause of supplementation(Reference Howard, Howard and Lanphear21, Reference Alikasifoglu, Erginoz and Gur23, Reference Kurinij and Shiono26). Water has no nutritional value and there is no medical indication for use, while sugar water may include glucose polymers given as a treatment for hypoglycaemia. Supplementation with formula may have health implications for the infant (related to early introduction of foreign proteins to the mucosa/gut) and should, according to WHO, be considered only when indications are convincing(Reference Weaver, Laker and Nelson44, Reference Catassi, Bonucci and Coppa45).

We found that CS was associated with a higher risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month (Table 3) and between months 1 and 3 (Table 4). This is in line with several previous studies(Reference Kurinij and Shiono26, Reference Cattaneo and Buzzetti28, Reference Khassawneh, Khader and Amarin46). CS has also been associated with delayed initiation of breast-feeding and late onset of lactation(Reference Rowe-Murray and Fisher47–Reference Dewey, Nommsen-Rivers and Heinig49). However, not all studies have found an association between CS and cessation of full breast-feeding shortly after birth, or between CS and a shorter overall duration of exclusive breast-feeding(Reference Alikasifoglu, Erginoz and Gur23, Reference Cernadas, Noceda and Barrera24, Reference Scott, Binns and Oddy27, Reference Chung, Kim and Nam50). The results of studies are difficult to compare regarding the association between CS and breast-feeding due to differing CS delivery rates and post-delivery practices. In Norway, CS is predominantly used in connection with medical and obstetric high-risk conditions, and not upon maternal request. The CS rate in the present study was 12·9 % while the national CS rate in Norway is approximately 15 %(Reference Tollanes, Moster and Daltveit51). CS has been described as an obstacle to early breast-feeding initiation also in BFHI-designated hospitals, and separation of mothers and infants after CS should be avoided when possible and uninterrupted and prolonged skin-to-skin contact should be facilitated after birth(Reference Rowe-Murray and Fisher47).

In the present study, 12·9 % of the mothers reported breast-feeding problems during the first month. These included mastitis, sore nipples and other undefined breast-feeding problems (Table 3). The breast-feeding problems were of such severity that health personnel were contacted. Breast-feeding problems were associated with a higher risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month (Table 3). Studies that have examined the association between various breast-feeding problems (such as poor latch-on or nipple problems) have observed a shorter duration of exclusive or full breast-feeding during the first 6 months(Reference Cernadas, Noceda and Barrera24, Reference Santo, de Oliveira and Giugliani25, Reference Scott, Binns and Oddy27). Severe breast-feeding problems are almost always very painful, and may lead to cessation of full breast-feeding due to poor latch-on and consequent reduced milk production. However, our results showed that if mothers succeeded in breast-feeding fully during the first month despite experiencing breast-feeding problems, there was no associated increased risk of cessation of full breast-feeding during later time intervals. This supports the concept of a critical period during the first few weeks after birth during which breast-feeding women require more intensive follow-up and support.

There was a lower risk of cessation of full breast-feeding by the end of the first month when the infant was transferred to an NICU after birth (Table 3). This may be explained by the high prevalence of milk banks in Norway and the corresponding high use of human milk, especially for infants with birth weights of less than 1500 g(Reference Rønnestad, Abrahamsen and Medbø9, Reference Grøvslien and Grønn52). Mothers may also be more concerned about full breast-feeding when the infant is ill immediately after birth. Alternatively, these mothers may receive more help with breast-feeding.

Conclusions

Despite almost universal initiation of breast-feeding and a high proportion of breast-feeding, very few mothers reported full breast-feeding at 6 months in this large cohort of Norwegian women. The most pronounced decline in full breast-feeding occurred between months 3 and 4. Supplementary feeding with water, sugar water or formula during the first week, CS and breast-feeding problems were associated with cessation of full breast-feeding during the first month. Associations were also observed between cessation of full breast-feeding between months 1 and 3 and supplementation during the first week and CS.

In the context of the WHO guidelines to exclusively breast-feed for 6 months, our results suggest that supplementary feeding with water, sugar water or formula during the first week, breast-feeding problems and CS should be used as indicators for giving breast-feeding mothers extra support and follow-up during hospital stay and after discharge. These findings also support a restrictive approach to supplementation during the first week of life and warrant further study of the necessity of such supplementation.

Acknowledgements

The MoBa Study was supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant no. N01-ES-85433), the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant no. 1 UO1 NS 047537-01) and the Norwegian Research Council/Functional Genomics (grant no. 151918/S10). The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors have made a substantial contribution to the study concept and design. A.-P.H. is the main author and performed the statistical analyses in collaboration with A.L.B. A.M.G. was responsible for the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and critically revised the manuscript. Laura Haiek is acknowledged for her valuable reading of the final manuscript.