Alemtuzumab, a humanised anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, is a potent disease-modifying therapy used in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).Reference Cossburn, Pace and Jones 1 Secondary autoimmune disorders have been reported following treatment, thyroid disease being the most common.Reference Cossburn, Pace and Jones 1 There have been few reports of alemtuzumab-induced renal disease. Three cases of membranous glomerulonephritis, one of which also had weak positive anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies, and five cases of anti-GBM disease have been described.Reference Meyer, Coles and Oyuela 2 – Reference Singer, Alroughani and Brassat 5 In all five, anti-GBM disease was renal limited with no reports of pulmonary involvement or Goodpasture’s syndrome.

Here we report the first case of anti-GBM disease presenting as Goodpasture’s syndrome 3 months after the second course of alemtuzumab for treatment of RRMS.

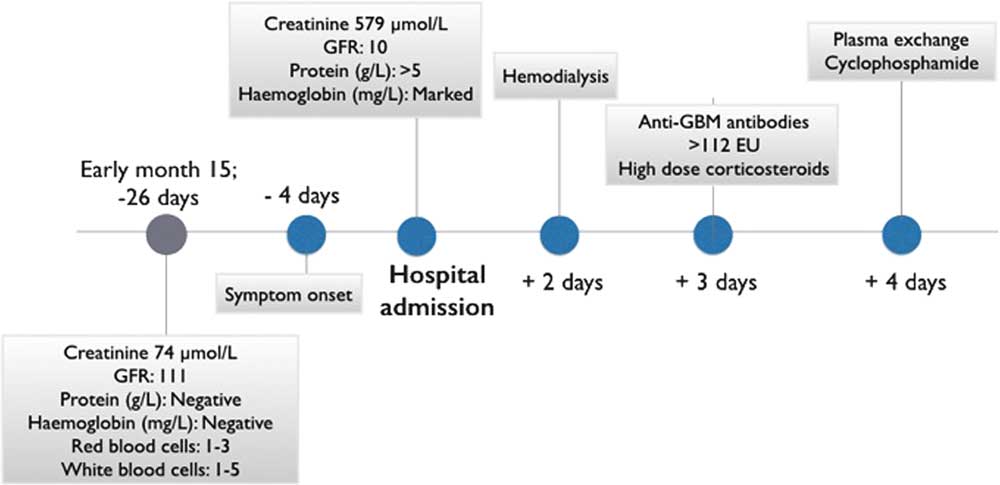

A 37 year-old Caucasian man, active smoker, with active RRMS of 8 years duration previously treated with interferon beta-1a received two courses of alemtuzumab for a cumulative dose of 96 mg. Results of follow-up routine investigations including creatinine and urinalysis were normal up to 3 months after completion of the second cycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Clinical evolution. Timeline of the evolution of the case depicting the main events from the last normal routine monitoring, including symptoms onset, hospital admission and management. Rapid progression from symptoms onset can be appreciated.

Twenty-two days after the last renal function testing, he developed low-grade fever, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. He noted one episode of gross hematuria and became abruptly oligoanuric. He presented to his local hospital 3 days after onset of symptoms with acute kidney injury and creatinine of 579 μmol/L. Urinalysis showed haemoglobinuria, proteinuria (≥5 g/L), and no casts. He was started on dialysis within 48 hours of admission and developed frank hemoptysis with CT findings suggestive of limited pulmonary haemorrhage (Figure 2). Anti-GBM antibodies came back highly positive (>112 European Units). Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. The patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroids, plasma exchange, and oral cyclophosphamide.

Figure 2 CT of the chest. An area of limited pulmonary hemorrhage is observed in the right middle and upper lung zones.

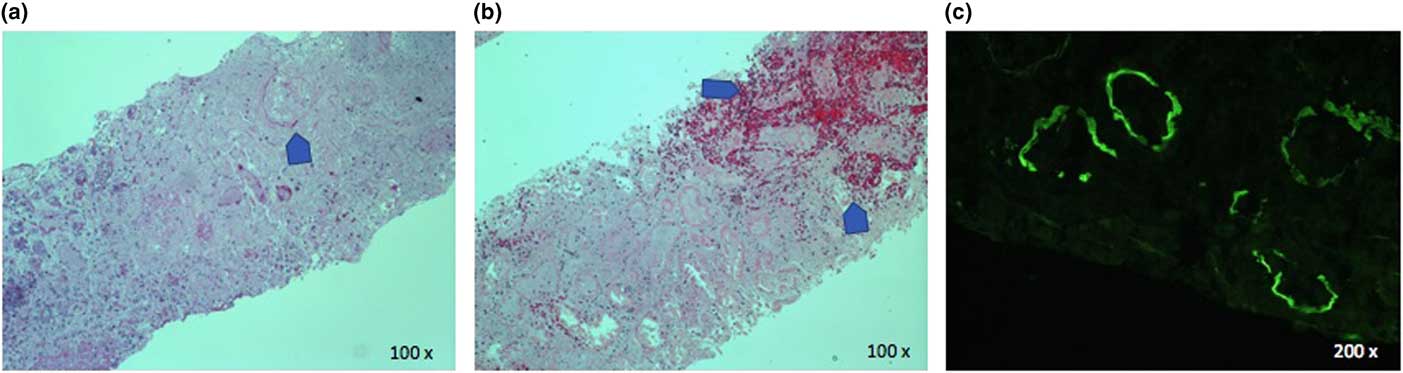

Renal biopsy showed haemorrhagic infarction of the cortex with no viable glomeruli and mixed inflammatory infiltration in the interstitium. Immunofluorescence revealed tubular basement membrane staining for IgG, C3, and kappa light chain (Figure 3). Despite the non-confirmatory biopsy, Goodpasture’s syndrome was considered the most probable diagnosis given the clinical presentation and high anti-GBM antibody titer. While the pulmonary haemorrhage resolved, there is still no renal recovery 9 months after diagnosis.

Figure 3 Renal biopsy. H&E stains show complete loss of glomerular architecture (panel a) and infarction and hemorrhage (panel b). Direct immunofluorescence shows linear tubular basement membrane staining for IgG (panel C).

Anti-GBM disease is a rare autoimmune disorder mediated by autoantibodies against an antigen of type IV collagen expressed on the glomerular and alveolar basement membranes.Reference Peto and Salama 6 It accounts for about 20% of all cases of rapidly progressive glumeronephritis.Reference Peto and Salama 6 The majority of patients present with concurrent pulmonary alveolar haemorrhage, eponymously referred to as Goodpasture’s syndrome,Reference Peto and Salama 6 although this is the first reported case with pulmonary involvement following alemtuzumab therapy in multiple sclerosis (MS) (Table 1). The progression of symptoms was unusually rapid in this case in comparison to the previously reported cases of anti-GBM disease following alemtuzumab therapyReference Meyer, Coles and Oyuela 2 – Reference Singer, Alroughani and Brassat 5 and to the known evolution of Goodpasture’s syndrome. In a retrospective analysis of 28 patients with Goodpasture’s syndrome, only 4% of the patients had developed acute onset of symptoms in the week preceding admission, whereas in up to 39% the symptoms had evolved over a month.Reference Lazor, Bigay-Game and Cottin 7 Oligoanuria, creatinine >500 μmol/L and immediate dialysis requirement at diagnosis, as in the present case, are strong predictors of long-term dialysis dependence.Reference Peto and Salama 6 , Reference Alchi, Griffiths and Sivalingam 8 Recovery is generally variable in anti-GBM disease.Reference Peto and Salama 6 , Reference Alchi, Griffiths and Sivalingam 8 Although few cases have been reported, permanent kidney injury has occurred in alemtuzumab treated MS patients who develop this complication with three of the five previously reported cases having evolved to chronic dialysis or transplant.Reference Meyer, Coles and Oyuela 2 – Reference Singer, Alroughani and Brassat 5

Table 1 Summary of previously reported cases of anti-glomerular basement membrane disease following alemtuzumab therapy in multiple sclerosis

Secondary autoimmune events occurrence is delayed following alemtuzumab therapy.Reference Baker, Herrod and Alvarez-Gonzalez 9 The most frequent autoimmune adverse event is thyroid disease, affecting 42% of the MS patients treated with alemtuzumab in the phase 3 studies through year 6.Reference Devonshire, Phillips and Wass 10 Thyroid events peak in year 3, with the most frequent being hyperthyroidism, including Grave’s disease.Reference Devonshire, Phillips and Wass 10 Immune thrombocytopenia is the second most frequent autoimmune adverse event, with an incidence of 2.3% in the alemtuzumab clinical development program.Reference Devonshire, Phillips and Wass 10 It also has a delayed occurrence with a mean timing of onset from the last alemtuzumab course of 17 months.Reference Devonshire, Phillips and Wass 10 Anti-GBM disease was diagnosed between 10 and 39 months after the last course of alemtuzumab in the previously reported MS cases, consistent with the timing of onset in this case.Reference Meyer, Coles and Oyuela 2 – Reference Singer, Alroughani and Brassat 5 The mechanisms underlying the development alemtuzumab-induced autoimmunity are not well understood.Reference Baker, Herrod and Alvarez-Gonzalez 9 Both B-cells and T-cells are involved in the pathophysiology of anti-GBM disease or Goodpasture’s syndrome,Reference Peto and Salama 6 and T and B cell reconstitutions after depletion by alemtuzumab have been postulated to drive secondary autoimmunity.Reference Baker, Herrod and Alvarez-Gonzalez 9 B-cells repopulate rapidly relative to T-cells and thus do so in the absence of regulation from T-cells, which could lead to the development of antibody-mediated autoimmune conditions such as Goodpasture’s syndrome.Reference Baker, Herrod and Alvarez-Gonzalez 9 MS and other autoimmune disorders can co-occur, and at least one case of anti-GBM disease has been described in an untreated MS patient.Reference Coles, Cox and Le Page 3 Some MS patients could have enhanced genetic susceptibility to anti-GBM disease, as the HLA-DRB*1501 allele has been associated with both conditions.Reference Peto and Salama 6 In addition, this patient had a first-degree relative with myasthenia gravis with antibodies to Muscle-Specific Kinase (MuSK) and he was an active smoker. A family history of autoimmune disease and current or past smoker status has both been identified as risk factors for secondary immunity in alemtuzumab treated MS patients, with odds ratio of 7.31 and 3.05, respectively.Reference Cossburn, Pace and Jones 1 Smoking also increases the likelihood of pulmonary involvement in Goodpasture’s syndrome and might have prompted the occurrence of lung haemorrhage in this case.Reference Peto and Salama 6

In summary, this case reflects the potential for extremely rapid progression and unfavourable outcome of Goodpasture’s syndrome developing after treatment with alemtuzumab in MS. It highlights the importance of periodic monitoring of creatinine and urinalysis following treatment, especially in light of the non-specific clinical presentation which may delay the treatment to preserve renal function.Reference Peto and Salama 6 Baseline testing of anti-GBM levels is of unclear predictive value as these autoantibodies may exist in asymptomatic carriers.Reference Peto and Salama 6 However, a high index of suspicion should be maintained for every alemtuzumab treated MS patient, and creatinine and urinalysis disturbances should be monitored closely with early referral to nephrology and anti-GBM testing. Caution should be exercised when prescribing alemtuzumab to active smokers and patients with a family history of autoimmune disorders who may be at increased risk of secondary autoimmunity.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Alexander Magil, renal pathologist at St-Paul’s Hospital, University of British Columbia, Canada, for providing pictures of the kidney biopsy.

Statement of Authorship

Each author has been involved in the case management, preparation, and revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures

EL has received consulting fees from EMD Serono, Biogen, and Hoffmann La Roche, as well as speaker fees from Genzyme and EMD Serono. BM and PN have no disclosures. KB has received compensation for consultation and a travel grant from Sanofi Genzyme Canada. ALT reports grants from MS Society of Canada, grants and personal fees from Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Chugai, Teva and Roche.