Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

2 - Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

Summary

‘The devil knows what's in our heads.’

A Georgian Proverb.‘The Persians are but women compared with the Afghans, and the Afghans but women compared with the Georgians.’

A Persian ProverbStalin and his enemies appeared to agree about one source of his identity as a political man. ‘I am not a European man’, he told a Japanese journalist, ‘but an Asian, a Russified Georgian.’ Trotsky cited Kamenev as expressing the views of the Central Committee in 1925: ‘You can expect anything from that Asiatic’, while Bukharin more pointedly referred to Stalin as the new Ghenghis Khan. Although they employed the term Asiatic to mean different things, their point of reference was the same. Stalin was born, raised, educated, and initiated as a revolutionary in a borderland of the Russian Empire that shared a common history and a long frontier with the Islamic Middle East. In this context, borderland refers to a territory on the periphery of the core Russian lands with its own distinctive history, strong regional traditions and variety of ethno-cultural identities. In a previous article, I sought to demonstrate how Stalin as a man of the borderlands constructed a social identity combining Georgian, proletarian, and Russian components in order to promote specific political ends including his vision of a centralised, multicultural Soviet state and society.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

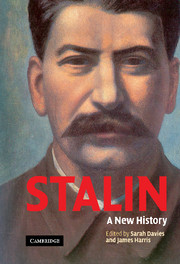

- StalinA New History, pp. 18 - 44Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005

- 5

- Cited by