Joseph Mukani, the manager of Mbeere Community Development Programme (MCDP), hurries into the small, cluttered office where I am waiting to interview him.Footnote 1 The office is located among the row of brightly painted, single-story shops, hair salons, and cafés that briefly line one side of a dusty dirt road, arising abruptly after miles of sparsely inhabited farmland and quickly disappearing again into fields punctuated by mud buildings with roofs made of thatch or iron sheeting. I have come to learn about NGO programming in the rural district of Mbeere, Kenya from this small organization, which is the local implementing partner of a large US-based nonprofit active in thirty countries around the world.Footnote 2

Mukani tells me about the NGO's activities, including training programs in agriculture, health, finance, and business development. He describes one training seminar the organization conducted on improving livelihoods through goat rearing, attended by self-help groups from around the district, as well as Ministry of Livestock officers eager to learn new techniques to pass on to others during their extension service activities. As he speaks, I wonder how effective the training – one of very many I heard about or witnessed – would be in changing habits on the ground, and whether paying for the government officials’ time and transportation to the seminar was worth the expense.

Mukani also describes a deworming program the organization conducted in the district to help the Ministry of Health. The deworming drugs, meant to be distributed to schoolchildren across Mbeere, were donated by a Scandinavian government aid agency and brought to the district office of the Ministry months earlier. The pills had not been distributed, however, as the Ministry office had neither a vehicle nor the funds to transport a staff member to schools throughout the district. MCDP stepped in to provide transportation and an allowance for a government officer to administer the pills to schoolchildren. “The government has the drugs, but they just expire if they don't get facilitation. So we add that,” he tells me. He is pleased with the interaction with the ministry. “It's a true partnership,” he says.

In addition, the organization works to support schoolchildren through a child sponsorship program for primary and secondary school students and early childhood development programs, and by rehabilitating and furnishing existing public school buildings. MCDP's goal is to provide a safety net for disadvantaged families in the area, and they rehabilitate three to six government schools each year. They have also improved government water services by extending pipeline several kilometers to reach a village that had not been connected to the public service previously.

When I ask explicitly about the organization's interactions with the government, the response is complex. Mukani states that MCDP makes its programmatic decisions independently from the government, but then says that he works closely with the Ministries of Agriculture, Livestock, Education, Health, and Public Works, and that he is a member of the District Development Committee, a government-led group that is meant to manage development activities in the district as a whole. He complains weakly about government inefficiencies, saying, “Government doesn't move that far the way we do. It takes them so much time [to do things].” But he then suggests that things are changing, since, “Service contracts are new in government, but are old at NGOs.” And he insists that, “NGOs also need government. They have certain institutions enabling [NGOs] to do their jobs.” At the end of the interview, he explains that most people in Kenya are more concerned about whether or not they get goods and services than about the type of organization the resources come from. He opines that government is needed for the long term. “NGOs came [to Kenya] when donors wouldn't give to government. If government worked, NGOs wouldn't be needed. NGOs know they're short term. Government should continue,” he concludes.

Much of the academic work on NGO–government interactions describes a hostile, conflictual relationship and asserts that NGOs often undermine developing states.Footnote 3 This view is encapsulated in Fernando and Heston's claim that “NGO activity presents the most serious challenges to the imperatives of statehood in the realms of territorial integrity, security, autonomy and revenue” (Reference Fernando2011, 8). The interview just described and most others I conducted in Kenya between 2002 and 2012, however, point to changes in this relationship and to a more complex reality on the ground. Rather than threatening the state, nongovernmental organizations have come to comprise part of the de facto organizational makeup of the state in many developing countries of the world. Under the right conditions, they have become part and parcel of public service administration through interpenetration with government. NGOs support state capacity and along the way enhance state legitimacy in the eyes of the citizens, who maintain both a pragmatic and wary view of the state and those who control it. Such a change is significant for weakly institutionalized states and their citizens, with both positive and negative implications.

This book traces the interactions between states, NGOs, and citizens to bring to light this emerging pattern of governance in developing countries. In doing so, it provides detailed answers to a number of important and related questions about NGOs, service provision, and state development. The book also addresses key questions about four “elements of stateness” – territoriality, governance, administrative capacity, and legitimacy:

What does NGO provision of services look like on the ground – what factors draw NGOs to work in particular locations, and what implications does NGO location have for territoriality?

How has the governance of service provision changed with the growth of NGOs over time? What changes do we see, not only in the way decisions are made and implemented, but also in the relationships between NGOs and governments? Under what conditions do we see collaboration or conflict in these relationships?

Does (or to what extent does) the provision of services by NGOs allow a government to shirk its duty to provide for the people? How has administrative capacity been affected?

Do citizens respond differently to provision of services by NGOs than they do to those provided by governments? Specifically, does NGO service provision undermine citizen perceptions of the state, or could it instead bolster state legitimacy?

The book draws on extensive evidence from in-country research in one developing country, Kenya, supplemented with data from Latin America, the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, and South, Central, and East Asia. It provides the reader with interrelated arguments about the changing nature of NGO–government relationships, the governance of service provision, state–society relations, and state development, which are outlined in this brief introduction.

What are NGOs?

A considerable literature has developed in order to conceptualize NGOs and related organizations (Salamon Reference Salamon1994, Uphoff Reference Uphoff1993, Vakil Reference Vakil1997, Werker and Ahmed Reference Werker and Ahmed2008). Most scholars agree that NGOs are private, not-for-profit organizations that seek to improve society in some way. Variation among organizations can be found in: where the organization first developed or is headquartered in the world; how it obtains funding; the scope of its activities (local, national, cross-national, international); whether it is a locally-formed, grassroots initiative of the poor or an elite-formed organization; whether it is a membership association or a professionalized organization; and whether it is secular or religious. NGOs are usually secular organizations, though they are sometimes registered in association with a church or other religious organization, making the strict characterization of NGOs as “secular organizations” inaccurate.Footnote 4 In Kenya, NGOs register with the NGO Coordination Board (NGO Board) of the government.

This book employs the definition of NGOs used by the Kenyan government at the time of research. The government defines NGOs as

A private voluntary grouping of individuals or associations not operated for profit or for other commercial purposes but which have organized themselves nationally or internationally for the benefit of the public at large and for the promotion of social welfare, development, charity or research in the areas inclusive but not restricted to health, relief, agricultural, education, industry, and supply of amenities and services.

I use this definition since most of the data in the book comes from Kenya, and the definition guided my data collection. In Kenya, it is also a useful definition because the government draws legal, regulatory, and registration distinctions between professionalized, formal NGOs and their Community-Based Organization (CBO) cousins. Most foreign-based, other-oriented charity groups and organizations are classified as NGOs, along with similar Kenya-based organizations.

Why are there so many NGOs now?

For the past 25 years, states around the world have witnessed the rapid growth of nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations providing goods and services in their territories. NGOs can be global players like OxfamFootnote 5 and CAREFootnote 6 that are headquartered in the West and have offices in nearly 100 countries; organizations like BRAC,Footnote 7 which began as a home-grown organization in Bangladesh and spread throughout the world; regionally important actors like Kenya-based AMREFFootnote 8 in Africa; large, single-country organizations; or small but formalized organizations working in one country or community. All NGOs undertake not-for-profit programming that aims to better the lives of individuals and societies. NGO work usually falls into the areas of healthcare, education, agriculture, the environment, humanitarian relief, and basic water and sanitation infrastructure.

Estimates vary widely on the present number of NGOs. According to the World Bank, international development NGOs based in rich countries grew from 6,000 to 26,000 between 1990 and 1999.Footnote 9 By 2010, thousands of NGOs were employing millions of people in Nigeria (Smith Reference Smith2010); nearly 8,000 NGOs were operating in Kyrgyzstan (Pugachev nd); tens of thousands of NGOs were in Bangladesh, with at least one in nearly 80 percent of villages (Rahman Reference Rahman2006); and more than one million organizations were operating in India (McGann and Johnstone Reference McGann and Johnstone2006). Regardless of the exact number of NGOs, the position of these nongovernmental organizations has shifted from that of minor and little-discussed players focusing on the welfare of the poor to major, central actors on the world stage of development, receiving, in some cases, more donor funds than their state counterparts (Chege Reference Chege1999, Doyle and Patel Reference Doyle and Patel2008, Batley Reference Batley2006, Mayhew Reference Mayhew2005).

NGOs rose to the forefront of discussion in international development conversations as part of a paradigm shift from a belief in government-led development to dedication to private-led development (Kamat Reference Kamat2004). While the particulars differ, the historical patterns are similar in developing countries around the world. In the years following World War II, post-colonial states promised to improve basic services such as education, infrastructure, and security for their citizens. Initially, states were able to make good on these promises. From the 1940s through the 1970s the consensus among not only national policymakers, but also international economists and development banks, was that the state was the actor capable of developing an economy due to the many market imperfections in poor countries (Bates Reference Bates1989, Hirschman Reference Hirschman1981). Young “developmental state” (Johnson Reference Johnson1982) governments therefore became pervasive, involved in all elements of the economy, service provision, and welfare (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire2001). In much of sub-Saharan Africa, states quickly became the largest employers, creating thousands of new jobs in the civil service, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), schools, clinics, and infrastructure projects.Footnote 10 In many poor countries, growing numbers of university-educated students saw the civil service as their future employer (Prewitt Reference Prewitt1971, Barkan Reference Barkan1975), and were actually guaranteed employment (van de Walle Reference van de Walle2001). With governments focused on import-substituting industrialization, state-owned factories and manufacturing plants absorbed many graduates.

For many states this period of easy expansion was short-lived. Patronage-based systems resulted in politically – not economically – rational policies (Bates Reference Bates1981). Goods and services were distributed to loyal clients in exchange for votes and support. Over time, these patterns created economic problems and perverse incentives within organizations (Ekeh Reference Ekeh1975). In many countries, farmers withdrew from commercial markets, reducing tax revenues (Bates Reference Bates1981). Added to these challenges were a series of economic disasters in the 1970s and early 1980s: oil shocks, plunging world market commodity prices, truncated industrial capability due to the increasing relative costs of imports, and a string of debilitating droughts.

By the late 1980s, most of the developing world had experienced prolonged economic stagnation. Meanwhile, an ideology of liberalization had gained strength in the West, where policymakers promoted deregulation, privatization, and reduced trade barriers as pathways to economic growth. International financial institutions and other donors quickly began to insist on economic liberalization as a precondition to loans and grants for developing countries. States were often required to liberalize exchange rates and financial markets, privatize or outsource public services, reduce trade barriers, trim national budgets, and maintain sustainable monetary policies in order to receive aid.Footnote 11

The role of the government in service provision changed dramatically over this period. Governments retreated from welfare and public good provision in order to reduce public expenditure and comply with the donor push for privatization. For example, Tanzanian social services as a percentage of government expenditure halved between 1981 and 1986, at the same time as fees for public services increased dramatically (Tripp Reference Tripp and Sandberg1994). In Kenya, spending on education dropped from 18 percent of the budget in 1980 to 7.1 percent in 1996, and in the health sector, government spending decreased from $9.82 million in 1980 to $6.2 million in 1993 and $3.61 million in 1996 (Katumanga Reference Katumanga and Okello2004, 48). By the end of the 1980s, political scientist Michael Bratton could write, “especially in the remotest regions of the African countryside, governments often have had little choice but to cede responsibility for the provision of basic services” (1989, 569).

Throughout the developing world, “the ‘roll-back of the state’ was accompanied by a growth in NGO service provision and the replacement of government structures by informal, nongovernmental arrangements” (Campbell Reference Campbell1996, 2–3 citing Farrington Reference Farrington, Bebbington, Wellard and Lewis1993, 189 and Bennet 1995, xii). Donors, armed with the norms of world society, strongly supported the growth of NGOs, and associations proliferated as these norms made headway (Schofer and Longhofer Reference Schofer and Longhofer2011). In the 1990s, for example, official development assistance (ODA) to NGOs increased 34 percent (Epstein and Gang Reference Epstein and Gang2006), and by 1999, most of USAID's $711 million in aid to Africa went to NGOs (Chege Reference Chege1999).Footnote 12 By contrast, in Kenya, ODA to the government halved between 1990 and 1994, and it halved again by 1999 (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2013), as donors maintained distrustful relationships with the government (Mosley and Abrar Reference Mosley, Abrar, Koeberke, Stavreski and Walliser2006). In such places, donors bypassed states with low capacity for governance, giving money to NGOs when they believed doing so would enable their support to achieve their intended outcomes (Dietrich Reference Dietrich2013). At the same time, many governments continued to channel monies, including aid, into maintaining patronage networks and procuring votes (Jablonski Reference Jablonski2014).

More recently, in the mid-2000s almost 50 percent of funds from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) and nearly 45 percent of funding for the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was directed toward NGOs around the world (Doyle and Patel Reference Doyle and Patel2008). In the 2010s, countries like Cambodia received as much as 20 percent of their international aid via NGOs (Suárez and Marshall Reference Suárez and Marshall2014). Nonprofits have been touted as more efficient, effective, flexible, participatory, democratic, accountable, and transparent than their government bureaucracy counterparts.Footnote 13

Over the years, NGOs have moved from providing supplemental charity and relief work to being increasingly involved in basic development and service provision based on a participatory approach (Brodhead Reference Brodhead1987). For example, in the Kenyan health services sector alone, NGOs now run nearly 90 percent of clinics and as many hospitals as the government (World Resources Institute 2003, 87). Alongside ministries of health, education, agriculture, and public works, we now see NGOs providing education, healthcare, child and women's assistance, agricultural extension services, employment, and even, in some cases, roads, wells, and other infrastructure. Thus, many of the goods and services that are today provided by NGOs were traditionally associated with states and governments; these services form part of the social contract between a state and its citizens (Campbell Reference Campbell1996, 9; Cannon Reference Cannon1996; Whaites Reference Whaites1998; Heurlin Reference Heurlin2010). Because of this overlap, many governments – especially those dependent on the distribution of patronage goods – exert strategies to maintain control over NGOs working in their territory (Bratton Reference Bratton1989). Despite these government efforts to maintain leverage over NGOs, we have come to see significant changes in the nature of NGO–government relationships, the governance of service provision, and state–society relations due to NGO activity.

What changes have resulted from NGOs?

The changing nature of NGO–government relationships

Comparative historical analysis of NGO–government relationships in Kenya and other countries reveals an increase in collaborative working relationships between NGOs and governments over the past 25 years. Where NGO–government interactions in developing countries were once dominated by mutual suspicion, distrust, conflict, and governmental control, over time they have become more cooperative, even positive and, in some cases, actively collaborative. This trend is not universal, but tends to be true in the presence of certain conditions: high-performing NGOs that focus on service provision rather than politics, human rights or corruption; stable government regulations, actions, and policy that demonstrate commitment to development and grant space for organizational autonomy; lack of competition for funding between NGOs and governments; and both types of organizations deliberately striving to create positive working relationships. Where these conditions are wholly absent or on the decline, however, conflictual relations become more common or even the norm.

In most parts of the world, however, collaboration and the conditions that facilitate it are driven by two factors. First, donor and funding organizations – not only multi- and bilateral donors, but also dominant philanthropic organizations – started requiring collaboration as a condition of funding (Ndegwa Reference Ndegwa1996). As specific examples, the percentage of World Bank projects that require active civil society organization participation increased from approximately 20 percent at the start of the 1990s to greater than 80 percent by 2010.Footnote 14 Likewise, the Global Fund, which disbursed US$2.5 to 3.5 billion annually between 2009 and 2012, requires recipients to work in partnerships of government, NGO, community, and private sector actors.Footnote 15 Governments and NGOs have had no choice but to work together, at least on a surface level.

Yet even in the absence of consistent donor presence, government and NGO relationships have tended to become more positive over time. This trend points to the importance of a second factor: social learning. Representatives from both NGOs and government agencies have grown over time to understand that it is in their mutual interest to work together. Through repeated interactions that facilitate the slow development of trust, leaders and managers in both types of organizations come to realize that there are win–win outcomes of engagement with the other sector. As Clark reminded us two decades ago, “Even ‘bad’ governments often have ‘good’ departments with which NGOs can work” (Clark Reference Clark1992, 153).

A limited number of academic articles have begun to document such changes across a range of countries and contexts, suggesting a generalizable phenomenon. Comparing West Africa's Gambia to Ecuador and Guatemala in Latin America, for example, Segarra (Reference Segarra, Chalmers, Vilas, Hite, Martin, Piester and Segarra1997) and Brautigam and Segarra (Reference Brautigam and Segarra2007) show that in all three countries, NGOs and governments failed in their first attempts at donor-encouraged partnerships in the 1980s and 1990s. By the 2000s, however, NGOs and their government counterparts were engaged in the collaborative implementation of programs and creation of policy to a great extent in Gambia and Ecuador, and to a lesser but apparent degree in Guatemala (ibid.). Segarra and Brautigam argue that these changes stem from the creation of trust during repeated iterations of interactions over many years, which allowed both governments and NGOs to learn that working together was in their mutual interest (ibid.). They cite a Gambian government official as saying “ten years ago … NGOs were seen as interfering, but we have now seen that they have strategic advantages” (Brautigam and Segarra Reference Brautigam and Segarra2007, 160). Like researchers working in other areas of the world (Rose Reference Rose2011, Pugachev nd), Brautigam and Segarra also credit donor requirements for collaboration as a crucial impetus for beginning interactions, and seeing partnerships as mutually beneficial (ibid.).

Elsewhere in Africa and Latin America, we find comparable stories. In Ghana, Atibil (Reference Atibil2012) documents a similar trend spanning Rawlings's transition from a military regime to an electoral system. She argues that psychological factors – specifically mutual perceptions of civil society organizations and the government – changed over time, creating space for positive relationships as well as political opening.

These trends are likewise visible in Asia. In a survey of Cambodian NGOs, nearly 60 percent of respondents reported positive working relations with government, and 40 percent shared complaints that they heard from community members with the government (Suárez and Marshall Reference Suárez and Marshall2014). In the health sector in Pakistan, moreover, governments increasingly recognize the boost that they receive from collaboration with NGOs to increase service provision (Ejaz, Shaikh, and Rizvi Reference Ejaz, Shaikh and Rizvi2011). Over time, the Government of Pakistan has learned that working with NGOs allows it to do things that it could not have done by itself (ibid.) and it has changed some of its policies accordingly to increase complementarity of service provision (Campos, Khan, and Tessendorf Reference Campos, Khan and Tessendorf2004). As a result, collaboration between the government and NGOs has grown over the past two decades. Similar trends are occurring in the health sector in Bangladesh, although relationships can still become hostile (Zafar Ullah et al. Reference Zafar Ullah, Newell, Ahmed, Hyder and Islam2006). Governmental policy and regulation have changed over time to facilitate these more collaborative relationships (ibid.). Although tensions between NGOs and governments persist in both countries and in India, “the policies of partnership have not only come to stay but are also becoming increasingly institutionalized” due to donor pressures and changing socio-political environments (Nair Reference Nair2011, 253).

Even in China, local governments are increasingly collaborating with charities and nonprofits to deliver services like education and healthcare (Teets Reference Teets2012). Although these relationships generally take the form of contracting rather than co-production, they are still signs of growing government willingness to work with nongovernmental organizations. These collaborations reflect movement away from direct control of the society by the state, and instead toward state supervision of the market and society, integrating civil society into a more pluralistic policy environment (ibid.).

The governance of service provision

These collaborative NGO–government interactions have led to significant changes in the governance of service delivery, both in the implementation of services among public and nongovernmental organizations and in decision-making around public service provision. In both domains, increased collaboration has resulted in a blurring of the boundaries between government and nongovernmental organizations and programs, as NGOs gain de facto or “practical” authority (Abers and Keck Reference Abers and Keck2013) alongside government actors in the country. At times, it is difficult to tell where the government ends and the NGO begins.

On the implementation side of governance, NGOs and governments have increasingly worked together to provide services. In Kenya, NGOs and line ministries pool resources for joint projects, NGOs pay for activities that allow the government to fulfill its mandate, experts from government ministries are seconded to NGOs to oversee the implementation of technical programs, and NGOs rent office space within government ministry buildings, physically co-locating. NGOs raise the capacity of the state to provide services by extending the reach of government some degree farther than it could go in the NGOs’ absence – sometimes quite literally, as when an NGO provides petrol to power a Ministry of Agriculture vehicle to a remote village to work with farmers. Rather than letting governments “off the hook” in their promise of service provision, NGOs supplement government activities. Individual civil servants involved in joint programs – especially extension officers – report doing more of the work they were trained to do, not less. In most parts of the country, government organizations of service administration remain the primary provider of services. Yet in far-flung places that are remote or difficult to reach, NGOs often play the part of government, broadcasting public service provision to a greater swath of the territory.

On the decision-making side of governance, similar patterns emerge. In most places, governments take the lead in service delivery decision-making. Yet rather than dictate what NGOs are to do, the government now invites NGOs to sit on national and local policymaking committees and integrates NGO plans and budgets into national and local planning. As a representative example, one district of Kenya proposed 149 service delivery projects in its five-year planning document (2008–2012); of these, 44, or just less than 30 percent, were to be funded or implemented by NGOs working in the area, based on the NGOs’ own plans.

One important result of collaborative service provision comes in the form of a very slow movement toward greater transparency and accountability within the civil service in Kenya. In essence, we see a process of institutional isomorphism within agencies of government, as they very slowly adopt the practices of their NGO partner organizations. This shift gradually raises the administrative capacity of the state. It must be stressed that these changes are small and slow, and that the quality of service provision and of government accountability still remain extremely low in places like Kenya.

Still, we should not dismiss movement toward democratic governance, however slight. Some of these changes come from deliberate strategies that government agencies use to obtain capacity-building training programs from NGOs or bring successful NGO leaders into prominent government positions. Others changes appear to be less intentional outcomes of social learning (Segarra Reference Segarra, Chalmers, Vilas, Hite, Martin, Piester and Segarra1997); government workers see the praise NGOs providing services get, and they mimic NGO activities. As Ndegwa (Reference Ndegwa1996) has shown, even NGOs’ “mundane activities” of everyday service provision can empower grassroots communities to engage their government.

Despite small signs of such changes, however, NGOs’ methods of service implementation make it difficult to clearly or objectively measure the impact of NGO programs. This measurement challenge is due in part to collaborative working relations, in which indirect NGO funding makes it impossible to tease out causality in increases or decreases in service provision. Yet it is also difficult to measure impact because NGOs are not always particularly effective or efficient organizations. They do not, for example, necessarily spend their funds in the most cost-effective manner – sometimes, this inefficiency is due to their own donors’ conditions or requirements, but on other occasions it is because there is “a lot of cheating done by NGOs” with money (2007–1Footnote 16). Many of the funds that NGOs bring to programs must be used for one-time expenses on durable goods, such as vaccines, school buildings, or boreholes, or on educational training programs, most of which end up being short-term seminars. Many NGOs (and the public or private donors behind them) are rightly criticized for favoring short-term, financially sustainable programming, such as single-day trainings on any number of topics, rather than long-term investments in human capital via health or education programs’ staff salaries, or intensive, long-term education for promising individuals.

On the flip side, NGOs do tend to have the resources and the flexibility to experiment with new types of programs in a way that governments do not. Much as US states are seen as a testing ground for US federal policy, NGOs can be seen as testing grounds for national policy in developing countries. Several clear programmatic successes have come from these experiments, most notably forms of conditional cash transfers.

Service provision, the social contract, and state–society relations

How do such changes to service provision and governance affect the people receiving services? More specifically, how does NGO provision of services affect perceptions of the state? It has been argued elsewhere that nonstate service provision can sever the social contract between state and society: as people receive services from nonstate actors rather than from their government, their loyalty to the state declines as their loyalty to the NGOs increases. NGO provision of services can, therefore, threaten a state's legitimacy (Bratton Reference Bratton1989, Jelinek Reference Jelinek2006, Doyle and Patel Reference Doyle and Patel2008, Batley and McLoughlin Reference Batley and McLoughlin2010, McLoughlin Reference McLoughlin2011). With such logic in mind, authoritarian governments throughout the world have clamped down on NGO activities, even those that are explicitly apolitical and do not seek social change. At various times in the past decade, for example, governments in Russia, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Kenya, India, Sri Lanka, China, and Afghanistan have reacted by banning some or all NGOs and their funding sources.

Evidence reveals that such action is unnecessary. Rather than reflecting poorly on the government, receiving services from NGOs has either no effect on or in fact improves Kenyans’ perceptions of the state. The strongest explanation for this phenomenon is somewhat paradoxical: Kenyan expectations of their government are exceedingly low; as such, the provision of services – regardless of their origins – is seen in positive terms, and credit for service provision is diffuse. Government actors, especially politicians, often slyly claim credit for the work done by NGOs, but Kenyans also appear to be willing to give government agents credit. This attribution is not due to people confusing NGOs with the government; Kenyans generally know the origins of services they receive. Most Kenyans do not link NGO service provision with government failure to fulfill the social contract because they seem to understand and even accept the limitations of their government.

Implications for state development

The foregoing arguments have crucial, yet mixed implications for developing states, whose very nature is changing because of NGO penetration. For decades in many of these states, the modal form of the state has been neopatrimonialism (Bratton and Walle Reference Bratton and Walle1997) or “personal rule” (Jackson and Rosberg Reference Jackson and Rosberg1984b, Leonard and Strauss Reference Leonard and Strauss2003). These states are characterized by highly concentrated power and extremely high levels of patronage, largely arising in many countries as a legacy of colonialism (Ekeh Reference Ekeh1975). As NGOs gain salience, the manner of governing in these patrimonial states may also change, albeit very gradually.

The growth of NGOs and the mindset they put forth encourage more equitable, participatory, and a politically motivated distribution of resources and services, since private actors, and international nonprofits in particular, tend to be less subject to clientelistic demands. Governments, seeing the positive response NGOs get from the people, mimic these strategies. As a result, the growth of NGOs providing a range of services within developing countries allows more to be done. On the whole, even when many NGOs are not particularly effective or efficient organizations, more services are provided to more people where NGO engagement is high than would occur in their absence. As NGOs and governments work together, moreover, government actors, especially civil servants in public administration, learn from their NGO counterparts, who have experimented with a range of program options. Improved accountability trickles into the public service, raising the level of public administrative capacity.

NGOs do more than run parallel programs or train civil servants, however. NGO presence can change the nature of the state in the twenty-first century, as NGOs become part and parcel of public service delivery – in essence, part of the institutionalized, organizational form of the state in development. In territorially far-flung places in particular, NGOs act as the state in service provision. They have gained “practical authority” alongside state actors, as they demonstrate problem-solving capacity and gain recognition for doing so (Abers and Keck Reference Abers and Keck2013). In bringing services, they also bring hope for the future to people with few expectations that their government will provide, despite its rhetoric.

In an age where scholars have asserted the “erosion of stateness” in Africa (Young Reference Young, Rothschild and Chazan2004) and have famously declared traditional forms of development aid to be noxious and “dead” (Moyo Reference Moyo2009), this study provides an important empirical assessment of both aid via NGOs and the developing state. It shows that where states are relatively weak, NGOs bolster public services and governance.

Thus the state has not been supplanted by NGOs; rather, it has been supplemented by them. This is not without potential downsides, however. Although there is currently a clear role for private nonprofit organizations in governance, the long-term viability of relying on NGOs for the governance of service provision is questionable. First, funding for NGOs fluctuates considerably, leaving recipient countries that depend on them in a precarious position. Second, reliance on NGOs often puts some degree of decision-making in the hands of foreign actors, including NGOs’ donors (Morfit Reference Morfit2011), which may be objectionable if we believe in home-grown solutions. Even if we accept foreign-originating ideas, relying on donor-funded NGOs is only a tenable state of affairs as long as the donors are benevolent. Third, although NGOs do tend to have the interests of recipient communities in mind, they are not democratically accountable to citizens of developing countries, and are financially accountable only to their donors. Fourth, NGOs, unlike governments, can pull out of a country or a community without notice or explanation. Citizens of such communities rarely have recourse when this occurs, since NGO programs tend to exist on a voluntary basis.

Governments of developing countries, unlike NGOs, are in a country for the long haul, and they are, at least in principle, accountable to their citizens. Because of this status, investing in government development, meaning the development of purely public agency capacity, may be a more fruitful means of ensuring service provision over the long term.

The question is not only one of reliance on NGOs or governments, however; negative implications of NGO activities can be more complex. In many developing countries, governments do not seem to have the interests of their citizens at the forefront of their minds. Many governments are corrupt, if not downright predatory. In such cases, NGOs providing services to the population may actually prolong the tenure of a bad government. By providing services that lend legitimacy to the state, NGOs run the risk of propping up such regimes. In some cases, NGOs cannot prevent governments from taking credit for their work, but if their services are placating the populace, such action may not be in a country's long-term interests. NGO work certainly can and has been co-opted on many occasions as well – sometimes governments engage with NGOs for precisely that purpose. It is thus imperative that we think critically about the proper role for NGO engagement in service provision in developing countries.

Research design: multiple forms of analysis; multiple sources of data

This book is about the effects of NGOs on the developing state. To assess these outcomes, I use an “effects of causes” design (Goertz and Mahoney Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012, 41): rather than beginning with an outcome, Y, and determining how that outcome came to be, I begin with a causal factor, X, and examine how it has affected Y. In concrete terms, I begin with an empirical phenomenon, the proliferation of NGOs in the global South (X), and analyze how it has affected the state (Y).Footnote 17

The analysis in this book employs a mixed-method approach that weaves quantitative evaluation of original datasets and survey work together with qualitative analysis of the cross-national literature on NGOs, in-depth interviews, case studies, and other information gathered during twenty-two months spent in Kenya.Footnote 18 Secondary source materials from a range of government ministries, independent think tanks, NGOs, and donor organizations supplement primary source evidence.Footnote 19

The quantitative analyses employ three original datasets, one of which combines existing data in novel ways and two of which stem from surveys created for this research.Footnote 20 The first, used in the chapter on Territoriality (Chapter 4), contains information on NGOs, development indicators, and service provision levels across seventy administrative districts.Footnote 21 Data from government censuses, UNDP Human Development Reports, and seven different Kenyan government agencies and ministries were collected and combined with a complete database from the Government of Kenya's NGO Coordination Bureau (NGO Board), the government agency responsible for registering, monitoring, and assessing NGOs’ work in the country. The database not only lists each of the 4,210 NGOs operating in Kenya at the time of research, but also provides information on the areas of the country in which they work, facilitating analysis of territorial implications throughout the country.

The second dataset, used in Chapter 7, compares data from the early post-independence period of the late 1960s to the present day. Specifically, it uses my 2008 replication of a survey of secondary school students in Eastern Province first conducted in 1966–1967.Footnote 22 The survey asked questions about citizenship, nation building, and the state in Kenya. Comparing the two iterations of survey responses helps measure the causes of changes in perceptions of state legitimacy over time.Footnote 23

The final dataset, used in Chapter 8, comes from an original survey of 500 adults and determines current perceptions of the state, linking state legitimacy to governmental and nongovernment service provision more concretely. Respondents were asked from whom they receive the core state services of education, healthcare, and policing, the extent of their familiarity and interactions with NGOs, their views on NGOs and the government, and their level of political participation.Footnote 24 Some of the questions in this survey were modeled on Afrobarometer questions (see www.afrobarometer.org), facilitating comparison to Afrobarometer's national samples from the same year on particular questions, but most were original.

These statistical analyses are complemented by qualitative assessment of NGOs’ impact.Footnote 25 The book draws on semi-structured interviews I conducted with more than one hundred governmental and nongovernmental workers, government officials, and Kenyan citizens. Interviews covered such topics as the programs offered by NGOs and government respectively, organizations’ goals and motivations, funding sources, and relationships with local and national government offices and officers. They also probed the relationship between NGOs, Kenyans, and the state. I selected respondents from registries of NGOs working in the three primary districts as well as through snowball sampling.Footnote 26

These interviews provided much of the understanding that allows meaningful interpretation of statistical results in the manuscript. In particular, information gleaned from interviews facilitates understanding of causal mechanisms, and also provides data on the NGO sector in Kenya, NGO–government interactions historically and in the present time, service provision methods, and administrative processes.

I complement data from Kenya, a typical-case (Gerring Reference Gerring2001) study, with review of existing scholarship on NGOs, service provision, and governance in South America, Africa, the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, and Asia. I reviewed hundreds of academic articles on NGOs, in addition to work on state capacity, governance, and legitimacy. This secondary research facilitates statements on the generalizability of the Kenyan experience, which strengthens the validity of the results.Footnote 27

A typical case with temporal and subnational variation

Kenya is an important country of focus for research on NGOs and the state for a variety of reasons. Kenya is representative of many developing countries, and not only those in Africa. While Kenya is a fairly strong state by African standards, it falls near the middle of less-developed countries internationally: Kenya ranked 128th out of 169 countries in the 2010 Human Development Index (UNDP 2010), putting it at the very top of the “low human development” category, but below such “medium human development” countries as Cambodia (ranked 126), Equatorial Guinea (119), Honduras (108), and Turkmenistan (83). Likewise, Freedom House scored Kenya an average “partly free” 3.5 out of 7 in its annual Freedom in the World index (Freedom House Reference House2011), placing it squarely in the middle of the range of countries. Unlike some extremely poor or weak African countries, moreover, Kenya has a developed manufacturing and export sector, as well as a growing information technology sector, making it comparable with many of the countries of Latin America and Asia.

The Kenyan government has worked to track the development of the NGO sector in the country, and has made this and other statistical information available to researchers, allowing a general picture of the NGO sector in the country to be drawn. The Kenyan government allows foreign researchers to work in the country, provided they have the necessary, easily obtained research clearance and it does not limit research topics to any observable degree. Given these conditions, studying Kenya is pragmatic as well as representative.

The country also facilitates study of temporal and subnational variation. As Chapter 3 will detail in earnest, Kenya, like many states in Latin America, Africa, and Asia (Atibil Reference Atibil2012; Brautigam and Segarra Reference Brautigam and Segarra2007; Nair Reference Nair2011), has experienced changes in NGO–state interactions over time. It shifted from highly conflictual to much more collaborative state–society relations. Analyzing this case allows us, therefore, to understand the conditions that undergird both conflictual and collaborative NGO–state relations, as well as the factors that facilitate the change from the former to the latter.

In addition to interesting temporal variation, Kenya is a diverse country with significant subnational differences, which shed light on important trends related to NGOs. The number and per capita density of NGOs at the district level, for example, varied significantly across Kenya's 72 districts at the time of research, which facilitates an analysis of the ecological conditions that draw NGOs to locate their programs in particular places at the subnational level (see Chapter 4).Footnote 28 Subnational variation also comes in the form of level of urbanization, which can shape NGOs’ effects. In particular, the rural–town–urban divide is important in shaping how citizens view the state in relation to their interactions with NGOs. In studies of NGOs, street-level interactions in rural districts are often overlooked, yet NGOs have a greater capacity to address governance at the local level than they do at the national horizon (Clayton Reference Clayton1998). Individuals, moreover, are affected by the everyday acts of low-level civil servants and local politicians and not just by decisions made by elites in the capital city.

Subnational districts of interest

Original research for this manuscript was conducted primarily in urban Nairobi, the capital city; in a large town, Machakos town; and across two rural districts, Machakos and Mbeere. Supplemental interviews in the Naivasha, Nakuru, Kisii, Migori, and Narok districts of Rift Valley and Nyanza Provinces confirmed the validity of the findings.

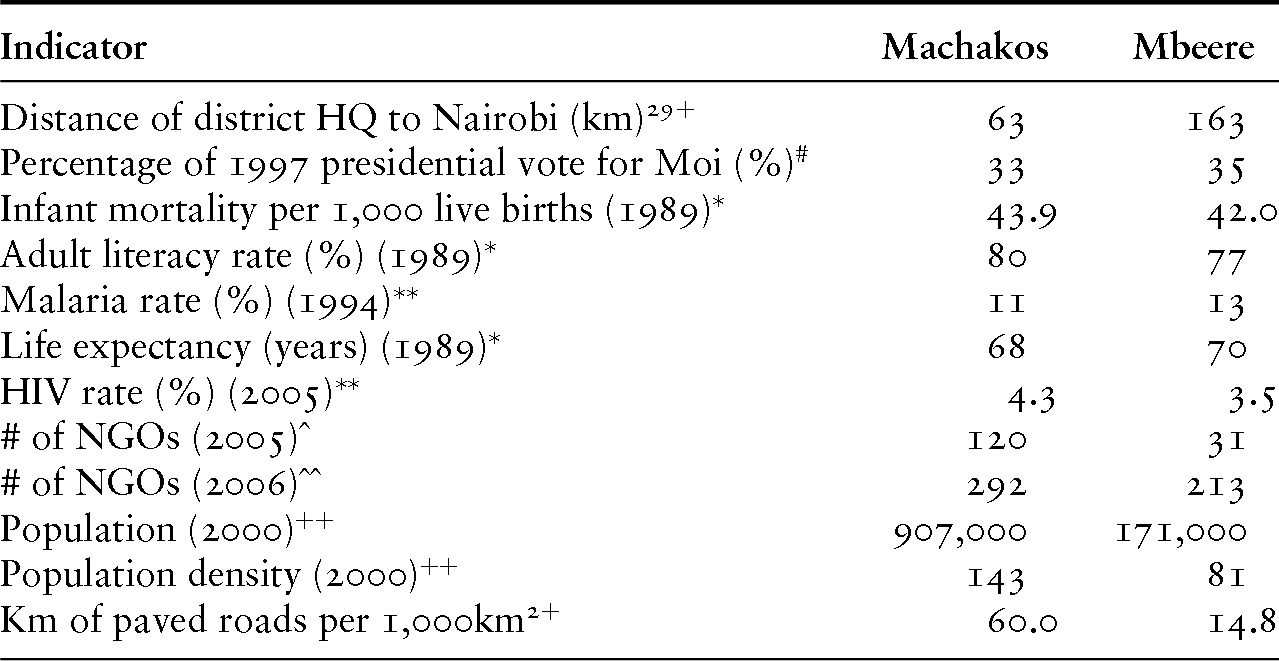

Machakos and Mbeere districts were chosen because they were similar in many regards during field research, but different in an important way, following Mills’ method of difference (see Table 1.1). The districts were approximately equidistant from the capital in terms of the time it took to reach them, and they had similar voting records in presidential elections, comparable infant mortality, literacy, HIV and malaria rates, and approximately the same life expectancy. At the time of research the two full districts had approximately the same level of NGOs per capita.Footnote 30

Table 1.1. Characteristics of Machakos and Mbeere districts

| Indicator | Machakos | Mbeere |

|---|---|---|

| Distance of district HQ to Nairobi (km)Footnote 29+ | 63 | 163 |

| Percentage of 1997 presidential vote for Moi (%)# | 33 | 35 |

| Infant mortality per 1,000 live births (1989)* | 43.9 | 42.0 |

| Adult literacy rate (%) (1989)* | 80 | 77 |

| Malaria rate (%) (1994)** | 11 | 13 |

| Life expectancy (years) (1989)* | 68 | 70 |

| HIV rate (%) (2005)** | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| # of NGOs (2005)^ | 120 | 31 |

| # of NGOs (2006)^^ | 292 | 213 |

| Population (2000)++ | 907,000 | 171,000 |

| Population density (2000)++ | 143 | 81 |

| Km of paved roads per 1,000km2+ | 60.0 | 14.8 |

Sources:

+ Republic of Kenya (2007).

# Arriola (Reference Arriola2013).

* Government of Kenya Census (1989).

** UNDP (2006).

^ National Council of NGOs (2005).

^^ NGO Coordination Bureau (2006).

++ Government of Kenya Census (1999).

The districts vary, however, in terms of level of urbanization. Machakos is more urban, with more towns – including an important commercial center, higher population density, and a higher proportion of paved roads than Mbeere. The districts’ headquarters were representative of these differences. Machakos town is a bustling, vibrant small city (municipal population of approximately 150,000) on the Nairobi–Mombasa highway, the overland artery of the country. Machakos town is also the seat of the County Council and the town with the greatest concentration of NGO offices, facilitating NGO–government interactions.

Siakago town, however, is very small, lacking both municipal status and a paved access road, which made travel to Mbeere's seat of government costly. It is about an hour's drive from the nearest city of Machakos town's size, Embu town. Mbeere district split from Embu district in 1996, but much of the activity in Mbeere still gravitates toward Embu town rather than Siakago.

The selection of these districts of focus reflect one significant trade-off (Gerring Reference Gerring2001) made in designing the research for this book – in data gathered in 2008, I controlled for political alignment and post-election violence, which partially limited variation in ethnicity and patronage. This was a conscious and necessary decision. On theoretical grounds, controlling for these other political factors allows us to isolate the generalizable effects of NGOs in service provision, rather than of ethnic patronage politics, which may be collinear. Politically, both Machakos and Mbeere and their majority ethnicities were aligned with the Kibaki administration during the time of research, but neither area was considered strongly supportive or strongly critical of Moi during his long tenure as president. In both districts, Moi earned about one-third of votes cast in 1997.

On practical grounds, much of the data collection for this book occurred in late 2008, not long after post-election ethnic violence wracked several parts of Kenya, resulting in the death of more than 1,000 people and the displacement of half a million others (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2008). The focus on Machakos and Mbeere controls for this violence, since there was limited or no violent conflict in them.Footnote 31 Note that most districts of Kenya experienced very little electoral violence (see http://legacy.ushahidi.com/ for a map of electoral violence in 2008), so the selection of districts without violence represents the norm. Most interviews and survey respondents identified as ethnically Kamba or Mbeere, but in Nairobi and the follow-up interviews, I also spoke with individuals from the Kikuyu, Kisii, Luo, and Maasai communities.

A roadmap of the chapters ahead

The analysis of NGOs and state development proceeds as follows. Chapter 2 provides conceptualizations of key terms used throughout the book, and it theorizes the relationship between NGOs and the state, specifically looking at four “elements of stateness”: territoriality, governance, administrative capacity, and legitimacy. In so doing, it introduces important scholarly theories that help the reader to understand changes occurring around the world related to NGOs, including those on civil society, governance and privatization, institutional isomorphism, and the social contract between a state and its people. It also provides the reader with an analysis of the various conditions under which NGOs and their government counterparts either collaborate or conflict with one another. These concepts, theories and conditions are then applied throughout the remaining chapters of the book.

Chapter 3 comprises a contextual background of the country case study, Kenya. The chapter provides the reader with a brief overview of the Kenyan political economy, followed by a detailed history of nonstate actors providing social services, and of NGO–government relationships within the country. Here, it primarily chronicles the transition from hostile NGO–government interactions during the Moi administration (1978–2002) to largely collaborative relationships during the Kibaki administration (2002–2012). The final section of the chapter turns to an overview of the NGO sector in contemporary times. It details the types of organizations present in Kenya, activities done, and the ways in which citizens engaged with NGOs in the early years of the twenty-first century.

Chapters 4 through 8 address the four elements of stateness, analyzing NGO implications for territoriality, governance, capacity, and legitimacy by turn. Chapter 4 examines the interplay between NGOs and territory, probing the factors that determine how NGOs choose the locations in which they work, and the impact that locational variation has on the territoriality of the state as a whole. It is worth noting that data from Kenya demonstrate that NGO placement is not determined by patronage politics, unlike most other service provision, but instead by a combination of need and convenience factors. On a per capita basis, moreover, data reveal that NGOs contribute to the territoriality of the state by locating in places where the state is weak and assisting the state to broadcast governing presence.

Chapter 5 probes the issue of governance, investigating how NGO involvement in service provision is changing patterns of both policymaking and policy implementation. The chapter demonstrates that NGOs have become intertwined with their government counterparts in service provision, resulting in increasingly robust overall provision. This change reflects a move toward polycentric governance, in which roles are shared and boundaries are blurred; NGOs become part of the organizational form of the state in service provision. At the same time, such changes are not without exception and limitations, which are analyzed in the latter half of the chapter. The chapter ends with a discussion of areas of continued tension between NGOs and government officials and potential downsides to NGO integration.

Chapter 6 moves inside the bureaucracy to examine changes to administrative capacity resulting from the proliferation of NGOs. Data from Kenya reveal that the blurring of boundaries and activities described in Chapter 5 resulted in increased capacity, as government actors learned the benefits of collaboration with NGOs and mimicked successful NGO strategies. At the local level, service-providing agencies became increasingly transparent, accountable, and participatory – a very slow movement toward more democratic governance of service provision. Overall levels of administrative capacity remained extremely low, however. Concerns exist, moreover, about how participatory, efficient or effective NGOs actually are.

Chapters 7 and 8 investigate NGOs’ impacts on state legitimacy. They use two different original survey instruments, Afrobarometer data, and in-depth interviews, to understand whether popular support for government changes in the presence of NGO activity, and to explain variation in such support. Chapter 7 investigates whether the legitimacy of the Kenyan state decreased in the face of NGO proliferation, comparing survey data from 1966, before NGOs, to replicated results in 2008, after NGO numbers surged. The data reveal that legitimacy levels in the 2000s were nearly identical to those in the early post-independence era. Endemic insecurity and corruption are negatively associated with state legitimacy levels, but NGOs are not.

Chapter 8 reveals that NGOs did not undermine state legitimacy in the early twenty-first century in Kenya. Although most Kenyans had more positive opinions about NGOs than they did about the government, NGO presence improved perceptions of government or had little effect. Support for NGOs clearly did not translate into a distaste for government. Qualitative analysis of interview data explains the main reason for this finding: the people of Kenya expected exceedingly little from their government, so they tended to be pleased to receive any services at all, regardless of the source.

The concluding chapter, Chapter 9, ties the threads together in an analysis of how our understanding of the state has changed as nonstate actors gain salience in many of the world's least-developed countries. In addition to synthesizing the findings of the empirical chapters, I draw on research from Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, and South, Central and East Asia, to show the applicability of my findings in Kenya to the situation in the wider world. The chapter concludes with discussion of remaining questions and implications for state development in the future.