Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

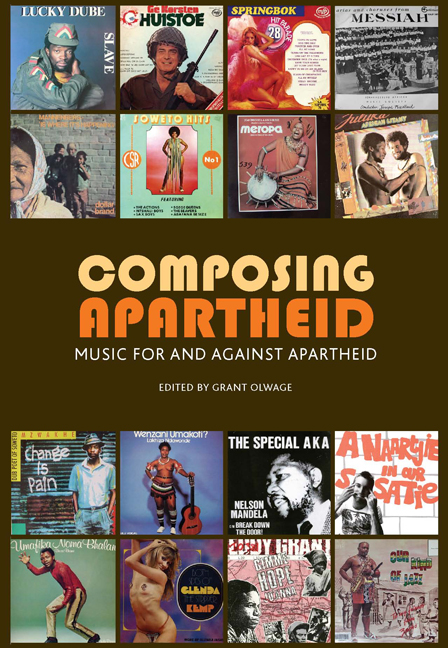

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Chapter 2 - Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

Imperial relations

Like most South African genealogies, apartheid's origins are a mixed up, miscegenated affair. Apartheid's gestation, however, is typically said to have occurred during the segregationist era, the half-century or so immediately prior to apartheid's official birth in 1948. Historians tell us that in the first decades of the early twentieth century, predominantly English-speaking ‘liberals’ sowed the seeds for a project of socio-political engineering they themselves named segregationism, ‘a composite ideology and set of practices seeking to legitimise social difference and economic inequality in every aspect of life’ (Beinart and Dubow, 1995: 4). Significantly, segregation was also in tune with imperial policy, both in the metropolis and in the colony for the representatives of Empire. For, if the growth of segregationism in South Africa was in part British-led it was because it had British interests at heart. This has been well documented for the large-scale political economy. But imperial relations were established also on the terrain of culture.

One area in which there's a clear (ongoing) relationship between imperialist capitalism and culture is, of course, the recording industry. The early history of the recording industry in South Africa is sketchy at best; the details we have pertain largely to the new media as it impacted on the black music market: black listeners were buying gramophone records already in the first decade of the twentieth century, black consumption of recordings increased dramatically in the 1920s, and the first recordings of black South African musicians were made more often in Britain than in South Africa (see Coplan, 1979: 143). Many of the first South African sonic products, then, were ‘manufactured’ elsewhere: materially produced in, and with, the Empire's capital, ideologically fashioning the Empire's subjects in order to make money. To put this bluntly: the segregated state of things in early twentieth-century South Africa, I argue, abetted imperial money-making in the music industry.

In the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century form of British imperialism, Empire was imagined (even if it did not always act) as functioning like a sort of multinational corporation with its headquarters in London. It follows that the idea, and ideologies, of Empire became important for consumerism in the Empire at large. In what Anne McClintock calls ‘commodity racism’, for example, race was imported into capitalism's marketing machinery (1995: chap. 5).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Composing ApartheidMusic for and against apartheid, pp. 35 - 54Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2008