11.1 Introduction

From 2000 to 2007, the United States experienced the most dramatic boom and bust in household debt since the Great Depression. Household debt increased at a steady pace through the 1990s, and then jumped by $7 trillion from 2000 to 2007. The boom in debt ended badly: by 2009, the delinquency rate on debt had reached above 10 percent, much higher than seen since the Great Depression. Figure 11.1 shows these patterns.

Figure 11.1 Aggregate Household Debt and Defaults

The left panel of this figure (Panel 1) plots nominal household debt according to the Federal Reserve Flow of Funds. The right panel (Panel 2) plots the default rate on household debt according to our sample of credit reports.

Our previous research on the housing and household debt cycle of 2000 to 2010 in the United States, summarized in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014a), made four main points:

From 2002 to 2005, there was an expansion in the supply of mortgage credit for home purchase toward marginal households that had previously been unable to obtain a mortgage, and this expansion was unrelated to improved economic circumstances of these individuals. We have referred to this fact as the extensive margin of mortgage credit expansion.

The expansion in mortgage credit availability and the increase in house prices were closely connected, but the expansion in credit was not merely a passive response to higher house price growth. Credit expansion was prevalent even in areas that experienced slow house price growth, and there is substantial evidence that house price growth during the boom was itself a result of credit expansion.

Existing homeowners borrowed aggressively against the rise in home equity values through cash-out refinancing and home equity loans, and this behavior explains the substantial rise in the household debt to GDP ratio from 2000 to 2007. This borrowing was strong among the bottom 80 percent of the credit score distribution. Only the top of the credit score distribution was unresponsive. We have referred to home equity–based borrowing as the intensive margin of mortgage credit expansion in previous research.

The sharp rise in delinquencies on household debt in 2007 was driven primarily by lower credit–score individuals living in areas where the house price boom and bust was most severe.

We have argued that these four points collectively support the credit supply view in which an increase in credit supply unrelated to fundamental improvements in income or productivity was the shock that initiated the household debt boom and bust shown in Figure 11.1.

In this study, we provide new evidence and highlight other research that supports the previously listed four points. In the process, we also discuss criticism of the credit supply view, which argues that credit played only a passive role in the housing boom and bust of 2000 to 2010. In this passive credit view, put forward most strongly by Foote, Gerardi, and Willen (Reference Foote, Gerardi and Willen2012) and Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016), mortgage credit simply followed the housing bubble and played no independent role.1 This alternative view is difficult to reconcile with numerous studies that show that the expansion in mortgage credit had a causal effect on house prices during the boom. The dramatic growth in house prices from 2000 to 2006 depended at least in part on the expansion of credit availability.

The credit supply view is not incompatible with the idea that unreasonable house price growth expectations were important. In particular, the initial credit supply shock may have been due to lenders having unrealistic beliefs about house prices. Further, existing homeowners likely borrowed so aggressively because they believed house prices would continue to rise. But the expansion in credit supply intermediated by the financial sector was a necessary ingredient in generating the boom and bust in household debt seen in Figure 11.1. This view has been formally modeled in a number of recent studies, including Favilukis, Ludvigson, and Van Nieuwerburgh (Reference Favilukis, Ludvigson and Van Nieuwerburgh2017) and Justiniano, Primiceri, and Tambalotti (Reference Justiniano, Primiceri and Tambalotti2015).2

Why are we still debating the causes of the housing boom and bust, eight years after the height of the mortgage default crisis? Determining whether credit played an active or passive role is important for a number of reasons. First, in the credit supply view, the financial sector plays an important role in explaining the mortgage boom and bust. As a result, an analysis of financial-sector activities during the boom such as incentives in securitization or fraudulent underwriting of mortgages is important to understanding what happened. Further, distributional issues come to the forefront because the financial sector transforms savings of some into borrowing by others. In contrast, under the passive-credit view, the financial sector is largely a sideshow. It simply followed the housing bubble like everyone else, and its actions had little independent effect on either the boom or the bust. Put differently, finance and capital structure play no role in this alternative view.

Second, the two views have different implications for economic modeling and our understanding of boom-and-bust episodes. A large body of research has shown a systematic relation between increases in household debt and subsequent economic downturns and financial crises (e.g., Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor Reference Jordà, Schularick and Taylor2016; Mian, Sufi, and Verner Reference Mian, Sufi and Verner2015). A growing body of theoretical models relies on changes over time in borrowing constraints, credit supply, or risk premia (as opposed to productivity shocks) to explain fluctuations in house prices, debt levels, and the real economy (e.g., Farhi and Werning Reference Farhi and Werning2016; Favilukis, Ludvigson, and Van Nieuwerburgh Reference Favilukis, Ludvigson and Van Nieuwerburgh2017; Justiniano, Primiceri, and Tambalotti Reference Justiniano, Primiceri and Tambalotti2015; Korinek and Simsek Reference Korinek and Simsek2016; Martin and Philippon Reference Martin and Philipponforthcoming; Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe Reference Schmitt-Grohè and Uribe2016). We believe the experience of the Great Recession supports the assumptions and conclusions of these models. The evidence and theory line up nicely, and they suggest that we have a solid understanding of the drivers of severe economic downturns. On the other hand, in the passive-credit view, we have little understanding of the ultimate causes behind boom-and-bust episodes such as the one we witnessed in the United States from 2000 to 2010.3

Third, and closely related to the previous point, the policy conclusions one reaches are different depending on which narrative is true. In the passive-credit view, regulation can accomplish little. For example, Foote, Gerardi, and Willen (Reference Foote, Gerardi and Willen2012) write that “critics might contend that treating bubbles like earthquakes is reminiscent of a doctrine often associated with Alan Greenspan: policy makers should not try to stop bubbles, which are not easily identified, but should instead clean up the damage left behind when they burst. To some extent, we concur with this doctrine, because we believe that policy makers and regulators have little ability to identify or to burst bubbles in real time.”

In contrast, the credit supply view argues that a consistent pattern emerges from the data: debt-fueled asset price booms, especially in real estate, typically end badly, and should therefore raise a red flag for regulators. The credit supply view suggests that more equity-based contracts may help reduce the amplitude of real estate booms, and make their busts less painful. Policies such as macro-prudential regulation targeting household debt-to-income ratios also follow naturally from the credit supply view. These policies are theoretically justified (e.g., Farhi and Werning Reference Farhi and Werning2016; Korinek and Simsek Reference Korinek and Simsek2016), and they have been implemented by the Bank of England, the Bank of Israel, the Bank of Korea, and the Swedish financial supervisory authority.

We use a number of datasets in the analysis that follows. We will describe most of the datasets as we utilize them, and others are already described in our previous research. The main dataset we utilize is individual-level Equifax credit bureau data, which is the same dataset used in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011). It is based on a 0.45 percent random sample of individuals in 1997 who were residing in ZIP codes for which Fiserv Case Shiller Weiss data are available. We sample these individuals and then obtain yearly credit bureau data through 2010. Although this sample is based on a limited number of ZIP codes, and new entrants are not included, the aggregate debt patterns for this sample closely match aggregate debt from the Federal Reserve Flow of Funds. We discuss these issues in more detail in the appendix.

11.2 Mortgage Credit Expansion on the Extensive Margin

The first main fact supporting the credit supply view is that lenders from 2002 to 2005 became more willing to extend home purchase mortgages to households that were traditionally denied credit. The increased willingness to extend credit to these households was not due to an improvement in the permanent income or productivity of these individuals. Let us first examine the aggregate evidence, and then we will present evidence from microeconomic data.

11.2.1 Aggregate Evidence

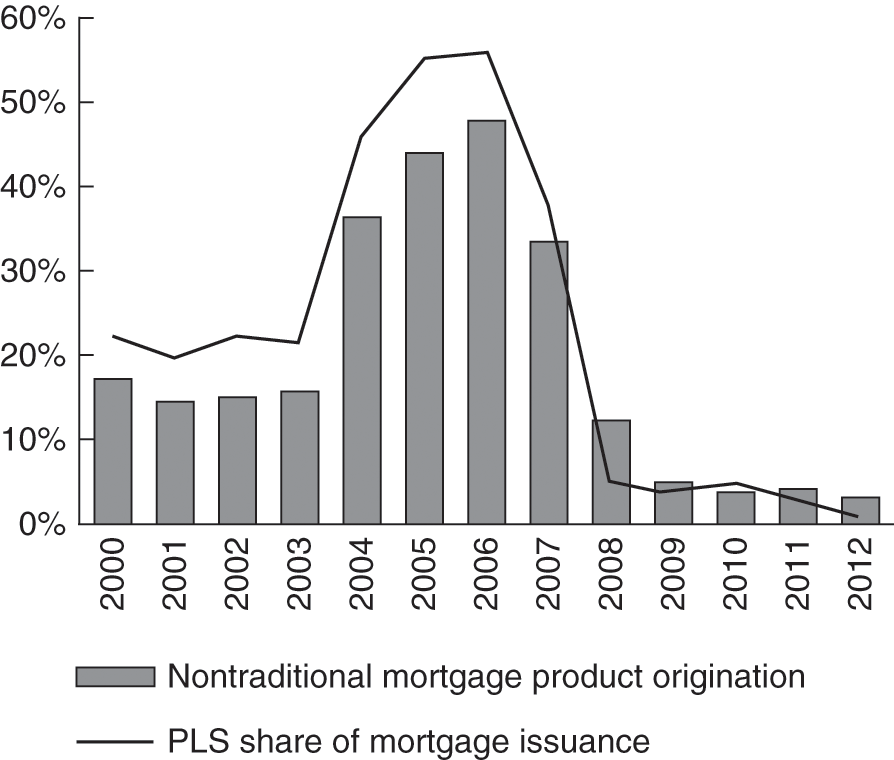

Levitin and Wachter (Reference Levitin and Wachter2012) show a dramatic expansion of mortgage credit originated and sold into the private-label, mortgage-backed security market from 2002 to 2005. The private-label, mortgage-backed security market went from 22 percent of originations in 2002 to 46 percent of originations in 2004 and then more than 50 percent in 2005. The total dollar amounts originated jumped from $200 billion to $800 billion (see 1198, fig. 2). As they put it, this was a market designed for “nonprime, nonconforming conventional loans.” In terms of interest rates, Demyanyk and Van Hemert (Reference Demyanyk and Van Hemert2011) show that there was a steady decline in the subprime mortgage to prime mortgage interest spread from 2001 through 2006 once loan and borrower characteristics are taken into account. They also suggest that their calculation understates the decline in the risk-adjusted spread because unobservable characteristics likely deteriorated more for subprime than prime borrowers.

During the mid-2000s, there was a simultaneous increase in the quantity of credit originated for nonprime borrowers and a decline in the interest rates faced by nonprime borrowers, exactly as would be expected with an expansion in credit supply.

Data from the American Community Survey show an increased willingness of lenders to originate credit for households that were traditionally denied mortgages. In Figure 11.2, we present the average characteristics of survey respondents who say that they both moved within the prior year and have a mortgage. We refer to these households as “recent homebuyers with a mortgage.” As a comparison, we also plot characteristics of all homeowners. The three characteristics we examine are income, age, and race. We pick these three characteristics because ZIP code–level evidence from 1997 reveals higher denial rates on mortgage applications for individuals living in lower-income, younger, more Hispanic, and more black ZIP codes.

Figure 11.2 Characteristics of Marginal Borrowers

This figure plots the characteristics of individuals with a mortgage that bought a home within the prior year and the characteristics of all homeowners. Compared to recent homebuyers in 2000, 2005 recent homebuyers with a mortgage saw a decline in income, a decline in age, and an increase in the fraction that was Hispanic.

As the top left panel of Figure 11.2 shows, from 2000 to 2005, the real median income of recent homebuyers with a mortgage actually fell. This is the only time from 1980 to 2005 such a decline occurred. The individuals buying a home with a mortgage in 2005 had lower real income than those who bought a home with a mortgage in 2000, which is strong evidence that a credit supply shift toward more marginal borrowers occurred during these years. As a comparison, real median income for all homeowners grew from 2000 to 2005, but at a slower pace than previously.

Over the same time period, the average age of recent homebuyers with a mortgage fell, which is also the only time this happened in the 1980 to 2005 period. The fraction of recent homebuyers with a mortgage who are of Hispanic origin increased substantially, while the fraction who was black remained constant. Relative to 2000, recent homebuyers with a mortgage in 2005 had lower income, and they were younger and more likely to be Hispanic. These are all characteristics associated with higher mortgage denial rates prior to 2000. These changes were unique to recent homebuyers with a mortgage: the average characteristics of all homeowners remained on a similar trend.

The expansion of credit to marginal borrowers is also seen in homeownership rates. As the left panel of Figure 11.3 shows, the homeownership rate increased sharply from 2002 to 2004, falling only slightly in 2005. However, we believe the homeownership rate is not the ideal measure of an increase in homeownership due to credit expansion. The homeownership rate is measured as the number of owner-occupied units scaled by the number of owner-occupied and renter-occupied housing units. This measure is problematic for two reasons. First, because the number of owner-occupied units is in both the numerator and denominator, an increase in the number of owned units will mechanically have a reduced effect on the homeownership rate through an increase in the denominator. Second, movements in the number of renter-occupied units can have an effect on the homeownership rate, and such movements are not directly related to extensive margin changes in homeownership. We discuss these two issues at more length in the appendix. A better measure of the extensive margin of expansion in homeownership is the total number of owner-occupied homes scaled by the adult population. We plot this ratio in the right panel of Figure 11.3, which shows a sharp rise from 2002 to 2004, and continues to rise from 2004 to 2005. A disadvantage of this measure is the numerator is only available from 2000 onward.

Figure 11.3 Homeownership Increased from 2002 to 2005

The left panel (Panel 1) plots the homeownership rate, which is defined as the number of owner-occupied housing units divided by the total number of occupied housing units. The right panel (Panel 2) shows the owner-occupied units per adult ratio, which is defined as the number of owner-occupied housing units divided by the total population of individuals 15 years old and above.

The homeownership rate data are collected by the Census. The Census also provides homeownership rates by subgroups including race, age, and income. Table 11.1 shows the change in the homeownership rate from 2002 to 2005, and from 2003 to 2005 for these subgroups. We provide the changes for both time periods because the homeownership rate for subgroups tends to be noisy. Consistent with the evidence from the American Community Survey, the Census homeownership rate shows a large increase in homeownership rates for young and Hispanic households for 2002 to 2005 or for 2003 to 2005. However, the evidence on income is less conclusive. From 2002 to 2005, the homeownership rate increased by more for households above median income, but from 2003 to 2005 we see the opposite pattern.

Table 11.1: Change in Homeownership Rates during the Mortgage Credit Boom

This table plots the change in the homeownership rate during the mortgage credit boom by age, race, and family income. All data come from the Census.

| Change in Homeownership Rate by Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 35 | 35 ≤ Age < 45 | 45 ≤ Age < 55 | 55 ≤ Age < 65 | 65 ≤ Age | |

| ∆ 2002 to 2005 | 1.025 | 0.725 | 0.050 | −0.075 | −0.075 |

| ∆ 2003 to 2005 | 1.550 | 0.875 | 0.150 | −0.100 | 0.200 |

| Change in Homeownership Rate by Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Hispanic | |

| ∆ 2002 to 2005 | 1.075 | 0.800 | 2.525 |

| ∆ 2003 to 2005 | 0.475 | 0.125 | 2.825 |

| Change in Homeownership Rate by Family Income | ||

|---|---|---|

| Above Median | Below Median | |

| ∆ 2002 to 2005 | 1.525 | 0.850 |

| ∆ 2003 to 2005 | 0.575 | 1.125 |

In general, homeownership rates by income from the Census are especially noisy. The coefficient of variation for the quarterly homeownership rate from 2000 to 2006 for those below the median income is substantially larger than the coefficient of variation for the U.S. homeownership rate. We have some evidence that potentially illustrates why. In 2010, the Census changed its methodology to impute income for households that do not report income. As a result of the imputation, the homeownership rate for individuals below the median increased by 1.9 percentage points in 2015 relative to without this imputation. It increased by only 0.2 percentage points for those above median family income. In other words, there appears to be systematic bias in the households that do not report income: they tend to be poorer. It is difficult to know whether this bias leads the Census to understate or overstate the rise in homeownership from 2002 to 2005 among low-income individuals. But we believe both the noisiness of the data and the fact that there is systematic bias in who reports income levels should lead researchers to use extreme caution with these data.4

11.2.2 ZIP Code– and Individual-Level Evidence

In Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), we utilized ZIP code–level data from Equifax and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), and we showed stronger growth in home-purchase mortgage originations in ZIP codes with a higher share of subprime borrowers as of 1996. We split ZIP codes into quartiles based on the fraction of subprime borrowers in 1997. From 1991 to 2002, the total dollar amount of home-purchase mortgages grew at a similar rate for the top and bottom quartile. However, from 2002 through 2005, the home-purchase mortgage amounts skyrocketed in low credit–score ZIP codes. The expansion of mortgage credit on the extensive margin in low credit–score ZIP codes from 2002 to 2005 was unprecedented in the 1991 to 2008 period.

In Figure 11.4, we use data from DataQuick by CoreLogic on the number of housing transactions in a ZIP code. In order to isolate housing transactions that are purchased for owner occupation, we match the address of the property to the address of the buyer where tax documents are sent.5 We also isolate the sample to transactions in which a mortgage was present.6 So Figure 11.4 measures the growth in owner-occupied transactions in which a mortgage is present, which should purge any effect coming from investment purchases. Similar to the analysis in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), we split ZIP codes into quartiles based on the fraction of subprime borrowers in 1997.

Figure 11.4 Number of Owner-Occupied Transactions, ZIP Code–Level Evidence This figure shows that both the number of owner-occupied housing purchases financed with a mortgage grew rapidly in low credit–score ZIP codes from 2002 to 2005. ZIP codes are split into quartiles based on the share of individuals with a credit score below 660 in 1997, and we show the top quartile (most subprime) and bottom quartile (most prime) by this measure. The number of owner-occupied transactions with a mortgage uses data from DataQuick by CoreLogic. All series are normalized to be 100 in 1998. The sample of ZIP codes is those that are in the Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) sample and are located in counties for which DataQuick has transaction data available for 1998 through 2010.

See the appendix for more details.

As Figure 11.4 shows, the number of owner-occupied housing transactions in the most subprime 25 percent of ZIP codes was similar from 1998 to 2000 relative to the most prime ZIP codes. There is a slight increase from 2000 to 2002, and then a large increase from 2002 to 2005. The number of properties bought for primary residence with a mortgage grew much more rapidly in low credit–score ZIP codes during exactly the period when credit supply expanded along the extensive margin.

Owner-occupied transactions increased substantially more in low credit–score ZIP codes from 2002 to 2005. In Table 11.2, we test whether investors increased their presence in these same low credit–score ZIP codes. Using DataQuick, we classify investor purchases in two ways. First, we classify a purchase as an investor purchase if the street name is different on the tax mailing address compared to the property address. Second, we use the ZIP code on the tax mailing address compared to the property address. Table 11.2 shows that, if anything, there was a relative decline in the investor share of purchases from 2002 to 2005 in low credit–score ZIP codes. Investor purchases cannot explain the larger mortgage credit and transaction growth in low credit–score ZIP codes from 2002 to 2005.

Table 11.2: Did the Investor Share of Purchases Rise in Low Credit–Score ZIP Codes?

This table uses DataQuick data from CoreLogic to examine whether the change in the investor share of purchases from 2002 to 2005 was larger in low credit–score ZIP codes. In columns 1 and 2, the definition of an investor is based on whether the street name of the tax mailing address is different that the street name of the property purchased. In columns 3 and 4, the definition is based on whether the ZIP code of the tax mailing address is different than the ZIP code of the property purchased. The sample includes ZIP codes from Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) that are also in DataQuick.

| ∆ Investor Share 2002 to 2005, Street | ∆ Investor Share 2002 to 2005, ZIP Code | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Fraction Subprime Borrowers, 1996 | −0.078*(0.030) | −0.052**(0.017) | −0.018(0.027) | −0.012(0.015) |

| Constant | 0.042** (0.010) | 0.034** (0.006) | 0.025** (0.009) | 0.023** (0.005) |

| County FE? Observations | No 1923 | Yes 1923 | No 1925 | Yes 1925 |

| R2 | 0.003 | 0.778 | 0.000 | 0.779 |

Growth patterns in mortgage debt among low credit–score individuals are also consistent with an expansion of credit along the extensive margin. In Figure 11.5, we use the individual-level Equifax data and we split the sample into five quintiles based on the Vantage Score in 1997. Individuals are placed into one of these five quintiles based on their 1997 credit score, and they remain in the same quintile throughout the sample period. Given the large number of individuals with zero debt, we aggregate the debt of all individuals within the category before estimating the growth rates, as opposed to taking the average of the individual growth rates. As the left panel shows, the bottom 20 percent of the credit score distribution saw a 300 percent increase in debt from 2000 to 2006. The growth rates are uniformly smaller as the credit score gets larger.

Figure 11.5 Low Credit–Score Individuals Experienced Largest Growth in Debt

This figure plots debt growth for individuals in credit bureau data, sorted by their credit score in 1997. Each quintile contains 20 percent of the population. In the right panel, we partial out age fixed effects to ensure that stronger growth for the lowest credit–score individuals is not merely an artifact of their younger age on average.

Is the higher growth rate in debt among lower credit–score individuals purely a function of age? Individuals in the low credit–score bin are younger, with an average age as of 1997 of 37 versus 44 for the middle quintile and 58 for the highest quintile (see the appendix for the differences across credit score quintiles). However, there is enough variation in age for individuals within the same credit score quintile that we can extract the growth effect independent of age. To produce the right panel of Figure 11.5, we first aggregate individuals into credit score by age bins, where we use the five quintiles of credit scores and age as of 1997 for the age bin. For each year of the sample, we regress annual growth of credit for each credit score by age bin on a set of age indicator variables and indicators for the five credit score bins. The coefficients on the credit score bins then give us the differential growth rate for each credit score quintile, controlling for age.

As the right panel of Figure 11.5 shows, such an age adjustment decreases the relative growth rate of the low credit–score quintile over the other quintiles. But even with these detailed controls for age, low credit–score individuals saw the largest growth in debt from 2000 to 2006. Finally, controlling for age in such a rigorous manner is an example of too many control variables. Prior to the debt boom, younger individuals were more likely to be denied credit. As a result, stronger mortgage credit growth by younger individuals could be interpreted as evidence of an expansion of mortgage credit on the extensive margin. Nonetheless, mortgage credit grew by more for low credit–score individuals, even taking out the age effect.

While Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) and the findings presented earlier emphasize the shift in credit supply toward marginal borrowers previously denied credit, credit supply likely expanded on other margins as well. For example, even consumers with high credit scores applying for mortgages may have faced lower interest rates or less stringent verification of income during the mortgage boom.

11.2.3 Other Research

In addition to Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), several other studies conclude that the early 2000s witnessed a dramatic expansion in mortgage credit toward marginal borrowers. For example, Mayer, Pence, and Sherlund (Reference Mayer, Pence and Sherlund2009) use a variety of datasets on subprime mortgages and conclude that “lending to risky borrowers grew rapidly in the 2000s … we find that underwriting deteriorated along several dimensions: more loans were originated to borrowers with very small down payments and little or no documentation of their income or assets in particular.”

Demyanyk and Van Hemert (Reference Demyanyk and Van Hemert2011) conducted one of the first academic explorations of the LoanPerformance data. As they wrote, “we uncover a downward trend in loan quality … we further show that there was a deterioration of lending standards and a decrease in the subprime-prime mortgage rate spread during the 2001–2007 period. Together, these results provide evidence that the rise and fall of the subprime mortgage market follows a classic lending boom-bust scenario, in which unsustainable growth leads to the collapse of the market.” Levitin and Wachter (Reference Levitin and Wachter2012) come to a similar conclusion: the “[housing] bubble was, in fact, primarily a supply-side phenomenon, meaning that it was caused by excessive supply of housing finance … the supply glut was the result of a fundamental shift in the structure of mortgage-finance market from regulated to unregulated securitization.”

Justiniano, Primiceri, and Tambalotti (Reference Justiniano, Primiceri and Tambalotti2016) use the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel and CoreLogic data to show that both mortgage debt growth and house price growth were stronger from 2000 to 2006 in ZIP codes with a high fraction of subprime borrowers as of 1999. This is similar to the results shown previously, and suggests that the results are robust to using alternative data sources. The authors further show that such a finding can be rationalized in a model where the fundamental shock is an outward shift in credit supply.

The results are also confirmed by Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016), who show in their summary statistics that home-purchase mortgage credit growth from 2002 to 2006 was strongest in ZIP codes with the lowest per capita income as of 2002. They show this using both the total amount of the mortgages, and the total number of mortgages. They also show that these same low-income ZIP codes saw the worst income growth from 2002 to 2006.

The fact that mortgage credit expanded along the extensive margin toward more marginal borrowers was viewed as relatively uncontroversial until recently. For example, Foote, Gerardi, and Willen (Reference Foote, Gerardi and Willen2012) wrote, “to our knowledge, no one has disputed the fact that from 2002 to 2006, credit availability increased far more for subprime borrowers than for prime borrowers – this growth was widely discussed as it occurred.”

11.3 Mortgage Credit and House Price Growth

In this section, we discuss the large body of evidence showing that expansion in mortgage credit availability caused an increase in house price growth; the evidence contradicts the argument that credit passively followed the housing boom.

11.3.1 Evidence from Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009)

In Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), we conducted two main tests to support the view that the expansion of mortgage credit pushed up house prices. First, we showed that house price growth was significantly stronger in low credit–score ZIP codes, despite the fact that these ZIP codes saw a decline in income compared to high credit–score ZIP codes within the same city. This was especially true in cities where geographical barriers induce a low elasticity of housing supply. To our knowledge, proponents of the passive credit view have never addressed this pattern. An explanation for the housing boom must explain why house prices rose the most in low credit–score neighborhoods within inelastic housing supply cities. The credit supply view provides a clear explanation: mortgage credit for home purchase was expanding rapidly in these neighborhoods, which pushed up housing demand. In inelastic housing supply cities, house prices rose in response to the demand shock.

The second technique we used in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) to support the view that credit supply pushed up house prices was to examine very elastic housing supply cities. In cities with very elastic housing supply, there was little house price growth from 2002 to 2006 and there was little reason to expect house price growth from an ex ante perspective. Yet even in these cities, mortgage credit expanded by more in low credit–score ZIP codes seeing a decline in income growth. When we shut down the house price growth expectations channel by focusing on elastic housing supply cities, we still see an expansion in mortgage credit to low credit–score individuals. This supports the view that the expansion in mortgage credit supply was not simply a function of house price growth or house price growth expectations. To our knowledge, advocates of the passive-credit view have not addressed this test from Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009). If the expansion of mortgage credit supply to marginal households was purely a function of house price growth expectations, why did such an expansion occur even in elastic housing supply cities with no house price growth?

Neither of these results implies the absence of a feedback effect from house price growth onto credit. As we acknowledged in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), “we want to emphasize that there may be a feedback mechanism between credit growth and house price growth … increasing collateral value may also increase credit availability for previously constrained households, which forces a cycle by further pushing up collateral value … in fact, our results lend support to such a feedback effect.”

11.3.2 Evidence from Other Research

The idea that an increase in mortgage credit supply caused an increase in house prices prior to the Great Recession is supported by an extensive body of research. Di Maggio and Kermani (Reference Di Maggio and Kermaniforthcoming) use variation in state anti-predatory laws in combination with the federal preemption of national banks in 2004 from such laws as an instrument for credit supply. They show that an exogenous increase in credit supply increased house price growth significantly. As they write, “a 10% increase in loan origination, through a local general equilibrium effect, leads to a 3.3% increase in house price growth, which resulted in a total increase of 10% in house prices during the 2004 to 2006 period.” They also show that credit supply expansion predicts the decline in house prices during the bust.

Landvoigt, Piazzesi, and Schneider (Reference Landvoigt, Piazzesi and Schneider2015) build an assignment model designed to understand the sources of house price growth within a city. They focus on San Diego county during the early 2000s to quantify the model. They conclude that “cheaper credit for poor households was a major driver of prices, especially at the low end of the market.” Using a completely different methodology, Landvoigt, Piazzesi, and Schneider (Reference Landvoigt, Piazzesi and Schneider2015) come to a similar conclusion as Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009): mortgage credit expansion caused an increase in house price growth, especially in neighborhoods with a disproportionate number of individuals previously denied mortgage credit.

Favara and Imbs (Reference Favara and Imbs2015) exploit the deregulation of restrictions on bank branching across the United States from 1994 to 2005. They show that such deregulation caused an increase in mortgage credit supply, and that the expansion in mortgage credit supply caused a rise in house prices. They also show that the effect of deregulation on house prices is mitigated in elastic housing supply cities, consistent with the idea that a credit-induced rise in housing demand increases house prices more in inelastic housing supply areas. The magnitude is large: the authors show that between one-third and one-half of the increase in house prices from 1994 to 2005 can be explained by the expansion in mortgage credit supply. While the sample period is not exactly the 2002 to 2006 period studied by others, the findings show that house price growth is affected by increases in mortgage credit supply.

Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2014) also show that exogenous increases in mortgage credit supply affect house prices. They exploit exogenous changes in the conforming loan limit set by the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and they find that houses that become eligible for cheaper funding because of these changes see a rise in value. While the average effect is small, they find that credit supply shifts “have a strong impact on particularly constrained households.”

It is worth mentioning that these studies each use a different empirical methodology to isolate exogenous shifts in mortgage credit supply. And they all find that an expansion in mortgage credit supply causes a rise in house prices. While the exact magnitude remains a debated point, the core conclusion does not: movements in house prices should not be viewed as independent of changes in mortgage credit supply.7

11.3.3 Investors, Speculation, and Housing Supply Elasticity

While the expansion of credit supply to marginal households was a chief determinant of house price growth during the 2000 to 2007 period, we do not mean to suggest it was the only factor. A recent body of research argues that speculation by investors, defined broadly as individuals or companies buying for a purpose other than residing in the property, was an important determinant of house price growth (Chinco and Mayer Reference Chinco and Mayer2016; Gao, Sockin, and Xiong Reference Gao, Sockin and Xiong2016; Nathanson and Zwick Reference Nathanson and Zwick2016).8

One of the key insights from these studies is that house price growth and construction were strong in some cities in the medium part of the housing supply elasticity distribution such as Phoenix, Las Vegas, and the Central Valley in Northern California. The studies show that strong house price growth in these cities was related to purchases by investors who were speculating on house prices. This point is related to the critique given by Davidoff (Reference Davidoff2013; Reference Davidoff2016) that housing supply elasticity is not a legitimate instrument for house price growth.

These studies convincingly show that the presence of investors was higher in elastic housing supply cities experiencing strong house price growth. In Table 11.3, we explore this finding to see how it is related to credit supply expansion. The house price growth data are from CoreLogic, and the housing supply elasticity measure is from Saiz (Reference Saiz2010). All of the regressions are weighted by the total population in the Core-based-statistical area (CBSA).

Table 11.3: House Price Growth and Housing Supply Elasticity: The Outliers

This table presents CBSA-level regressions relating measures of house price growth from 2000 to 2006 to housing supply elasticity. As has been pointed out, housing supply elasticity does not fully explain house price growth. However, controlling for housing supply elasticity, the extent to which marginal borrowers live in the CBSA prior to the housing boom has a strong effect on house price growth. All regressions are weighted by the total number of households in the CBSA as of 2000.

| House Price Growth, 2000 to 2006 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Housing Supply Elasticity | −0.246** (0.022) | −0.471** (0.047) | −0.494** (0.046) | −0.543** (0.047) | −0.428** (0.052) |

| Housing Supply Elasticity Squared | 0.041** (0.008) | 0.043** (0.008) | 0.046** (0.008) | 0.037** (0.008) | |

| Fraction Subprime Borrowers, 2000 | 1.422** (0.324) | ||||

| Ln(average income per capita, 2000) | −0.638** (0.119) | ||||

| Homeownership Rate, 2000 | −0.568* (0.282) | ||||

| Constant | 1.129** (0.045) | 1.351** (0.060) | 0.911** (0.116) | 8.064** (1.252) | 1.655** (0.162) |

| Observations | 253 | 253 | 253 | 253 | 253 |

| R2 | 0.339 | 0.405 | 0.448 | 0.467 | 0.415 |

In columns 1 and 2, we follow Gao, Sockin, and Xiong (Reference Gao, Sockin and Xiong2016) by regressing house price growth in a city on both the linear and squared housing supply elasticity measure. There is a very strong negative correlation between house price growth and housing supply elasticity, and the squared term is positive in column 2. However, the R2 is not 1, and so there are outliers to the relation.

In columns 3 through 5, we include measures of the presence of marginal borrowers in the city before the housing boom. In contrast to the within-city ZIP code–level variation in the presence of marginal borrowers used in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), we focus here on the between-city variation in the presence of marginal borrowers.

As columns 3 through 5 show, after controlling for housing supply elasticity, house price growth in a city from 2000 to 2006 is strongly positively related to the presence of marginal borrowers. The fraction of subprime borrowers is positively related to house price growth, and higher ex ante homeownership rates and income levels are negatively related to house price growth. The statistical power is very strong: the R2 including the income variable increases by 0.06.

The results in columns 3 through 5 of Table 11.3 show that the residual variation in house price growth after controlling for housing supply elasticity is closely related to the presence of marginal borrowers in the city prior to the boom. This is not to say that the investor channel proposed in the existing research is incorrect. But it does suggest that between-city variation in credit supply may have been an important factor explaining why some elastic housing supply cities saw rapid price growth. Indeed, Davidoff (Reference Davidoff2013) suggests the exact same mechanism in his critique of housing supply elasticity as an instrument. He points to the fact that Washington Mutual, one of the most aggressive subprime mortgage lenders of the 2002 to 2005 period, had a large market share as of 2001 in many of the elastic housing supply cities that saw strong house price growth.

11.4 Home Equity–Based Borrowing on the Intensive Margin

The expansion of credit supply to marginal borrowers alone could not possibly explain the tremendous rise in household leverage from 2000 to 2007. Marginal borrowers are a small part of the population, especially if one weighs by ex ante debt amounts in 2000. In Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011), we showed that the rise in household debt was driven primarily by existing homeowners borrowing heavily against the rise in house prices. While the marginal propensity to borrow out of a rise in home equity was strongest among low credit–score individuals, it was also positive among all but the top 20 percent of the distribution.

This fact can be seen in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014b), where we show the marginal propensity to borrow against home equity by credit score. Using the Vantage Score from Equifax as of 1997, we show that the marginal propensity to borrow out of a one-dollar rise in home value was 0.25 for individuals having a credit score below 700, 0.22 for individuals having a credit score between 700 and 799, and 0.10 for individuals between 800 and 899. For individuals with credit scores above 900, the marginal propensity to borrow is almost exactly zero. In our sample of homeowners, only 10 percent of individuals had a credit score above 900 as of 1997. In other words, homeowners throughout almost the entire distribution borrowed against home equity; only the very top of the distribution was unresponsive. While both Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011) and Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014b) use various strategies to isolate causality as best as possible, the basic insight can be seen in correlations. In Table 11.4, we use the individual-level Equifax data and we split the sample by both credit score in 1997 and house price growth from 2000 to 2007 of the ZIP code in which the individual lived in as of 2000. Each credit score bin contains exactly 20 percent of the population, and each house price growth bin also contains approximately 20 percent of the population.

Table 11.4: Share of Rise in Debt, by Credit Score and House Price Growth

This table shows means by 1997 credit score quintile and by house price growth from 2000 to 2007. Each individual is assigned the house price growth from 2000 to 2007 of the ZIP code in which he or she resided in 2000. The bottom panel shows the share of total debt increase from 2000 to 2007 for each cell.

| Credit Score Quintile | Share of Population, 1999 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Price Growth Category | |||||

| lt 40% | 40–75% | 75–105% | 105–130% | gt 130% | |

| 1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 5.4 |

| 2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 4.8 |

| 3 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 |

| 4 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| 5 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Credit Score Quintile | Debt level, 2000 (thousands $) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Price Growth Category | |||||

| lt 40% | 40–75% | 75–105% | 105–130% | gt 130% | |

| 1 | 32.3 | 34.0 | 32.4 | 33.9 | 28.9 |

| 2 | 63.6 | 69.0 | 65.4 | 68.8 | 59.5 |

| 3 | 75.4 | 84.2 | 76.8 | 82.1 | 73.8 |

| 4 | 65.2 | 78.0 | 66.3 | 68.7 | 64.0 |

| 5 | 76.0 | 90.1 | 77.1 | 84.0 | 76.3 |

| Credit Score Quintile | Share of Debt Increase, 2000 to 2007 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Price Growth Category | |||||

| lt 40% | 40–75% | 75–105% | 105–130% | gt 130% | |

| 1 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 5.6 |

| 2 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 6.9 |

| 3 | 3.7 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| 4 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| 5 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

The top panel in Table 11.4 shows the distribution of the population. If house price growth and 1997 credit scores were uncorrelated, there would be 4 percent of individuals in each bin. This is not the case, as low credit–score individuals tend to live in ZIP codes experiencing stronger house price growth from 2000 to 2007 (Mian and Sufi Reference Mian and Sufi2009). As the second panel shows, the level of debt in 2000 is closely related to credit scores, with the lowest credit–score individuals having the smallest amount of debt. As a result, even though the growth in debt was quite dramatic for these low credit–score individuals (reflecting the expansion of credit on the extensive margin), the increase in the total level of debt should be expected to be less dramatic than the growth rates.

Figure 11.6 shows how the level of debt evolved for individuals in each quintile based on 1997 credit scores. The level of debt went up substantially for the bottom 60 percent of the credit score distribution. It went up the least for the top 20 percent of the distribution. The total level of debt went up by the highest amount for individuals in the 20th to 60th percentile of the credit score distribution.

Figure 11.6 Increase in the Level of Debt, by Credit Score

This figure plots the average level of debt for individuals in the Equifax data, sorted by their credit score in 1997. Each quintile contains 20 percent of the population.

The bottom panel of Table 11.4 shows that the rise in the level of debt was closely related to house price growth. It presents the share of the total aggregate rise in debt by both 1997 credit score and house price growth from 2000 to 2007 bins. The six cells at the top right of the panel represent the low and middle credit–score individuals living in the high house price–growth ZIP codes. These individuals account for 33 percent of the aggregate rise in household debt, despite making up only 25 percent of the total population.

Further, as Table 11.4 shows, every credit score bin shows a larger rise in household debt as house price growth increases with the exception of the top credit score bin. There is no relation between house price growth and the rise in debt for the top credit score bin. Individuals with the highest credit scores were unresponsive to higher house price growth, as shown in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011) and Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014b).

11.5 Defaults

In Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009), we argued that the mortgage default crisis as of 2007 was “significantly amplified in subprime ZIP codes, or ZIP codes with a disproportionately large share of subprime borrowers as of 1996.” In Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011), we showed that the default rate for low credit–score homeowners who had borrowed aggressively against home equity during the boom rose sharply in 2007 and 2008. These facts suggest that credit expansion on the extensive margin in combination with aggressive borrowing against home equity by low credit–score homeowners were main factors explaining the initial sharp rise in defaults in 2007. Mortgage defaults triggered losses among large financial firms, and these losses mark the beginning of the financial crisis episode that peaked in the fall of 2008.

A real-time analysis of the media in 2007 confirms that the mortgage default crisis was triggered by defaults on mortgages to low credit–score individuals, and subprime mortgages in particular. For example, a MarketWatch story from February 27, 2007 reports: “shockwaves have been rippling through financial markets as more signs emerge that relaxed lending standards during the housing boom of recent years are leading to escalating defaults and rising losses for lenders and owners of securities backed by such loans.” New Century Financial Corporation, described in an article by Reuters on March 9, 2007 as “the largest independent U.S. subprime mortgage lender,” saw its shares fall 17 percent on March 9, 2007. In a March 13, 2007 article titled “Subprime shakeout could hurt CDOs,” MarketWatch discussed how losses in the subprime mortgage market would impact financial institutions through the mortgage-backed securities market.

In July and August 2007, the media emphasized losses on Bear Stearns’ hedge funds with large subprime mortgage exposure. An article on the German press website Spiegel Online on August 15, 2007 led with the sentence: “The US subprime mortgage crisis has hit banks and stock markets worldwide.” Regulators were also emphasizing problems in the subprime market quite early in 2007. For example, on May 17, 2007, Chairman Ben Bernanke gave a speech on rising defaults in the subprime mortgage market. This explains why the first wave of academic research focused on this market (i.e., Demyanyk and Van Hemert Reference Demyanyk and Van Hemert2011; Keys, Mukherjee, Seru, and Vig Reference Keys, Mukherjee, Seru and Vig2010; Mayer, Pence, and Sherlund Reference Mayer, Pence and Sherlund2009).

The individual-level credit bureau data confirm the anecdotal evidence from the media. Figure 11.7 shows the default rate among individuals based on their credit score as of 1997. As it shows, the default rate from 2005 to 2007 increased by seven percentage points for individuals in the lowest 20 percent of the credit score distribution. The default rate hardly budged for those in the top 40 percent of the distribution. In 2008 and 2009, default rates rose significantly for even higher credit–score individuals. However, this likely reflects the fallout of the initial mortgage default crisis, as banks pulled back heavily on mortgage lending and house prices began to rapidly fall. At the very least, the default rate among higher credit score individuals in 2008 and 2009 cannot be viewed as independent of the subprime mortgage crisis that erupted in 2007.

Figure 11.7 Default Rate, by 1997 Credit Score

This figure plots the default rate for individuals in credit bureau data based on their 1997 credit score. Each quintile contains 20 percent of the sample.

One concern about the default rate evidence in Figure 11.7 is that while default rates may be high for low credit–score individuals, the total credit outstanding to low credit–score individuals was quite small. We examine the total amount in default in the left panel of Figure 11.8. Recall that our Equifax sample is based on a 0.45 percent random sample of ZIP codes that make up about 45 percent of the U.S. population. We scale up the defaulted amounts by this sampling frequency to obtain total defaults.9

Figure 11.8 Total Defaults and Foreclosures, by 1997 Credit Score

This figure plots the total defaults and foreclosures for individuals in our credit bureau data based on their 1997 credit score. Each quintile contains 20 percent of the sample. The left panel (Panel 1) plots the total amount in delinquency for each quintile. The right panel (Panel 2) shows total foreclosures, which is measured as a flag in credit bureau data for a foreclosure in the past 24 months. We scale up the total defaults and foreclosures by the sampling frequency to obtain aggregates.

In 2007, of the $900 billion of delinquent household debt, $660 billion came from the bottom 40 percent of the credit score distribution. Only $81 billion came from the top 40 percent of the credit score distribution and $160 billion from the middle quintile. Put another way, let us suppose that borrowers in the top 60 percent of the credit score distribution did not default on one single dollar of debt. Even in such a counterfactual, total delinquent household debt would have been $660 billion in 2007, which is twice as much as the total delinquent debt as of 2003. Such a large amount of delinquent debt would have constituted an unprecedented default crisis, even had individuals in the top 60 percent of the credit score distribution avoided defaults entirely. Table 11.5 shows the share of all delinquent debt in 2007 by credit score quintile and house price growth quintile. Individuals in the bottom 40 percent of the credit score distribution with the highest house price growth during the boom make up more than 22 percent of defaults in 2007, despite being only 10.4 percent of the population.

Table 11.5: Share of Delinquencies, by Credit Score and House Price Growth

This table shows the share in delinquencies in 2007 by 1997 credit score quintile and by house price growth from 2000 to 2007. Each individual is assigned the house price growth from 2000 to 2007 of the ZIP code in which he or she resided in 2000.

| Credit Score Quintile | Share of Delinquent Debt, 2007 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Price Growth Category | |||||

| lt 40% | 40–75% | 75–105% | 105–130% | gt 130% | |

| 1 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 12.8 |

| 2 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 9.7 |

| 3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

By 2008 and 2009, the default crisis spread to higher credit–score borrowers. However, the bottom 40 percent of the initial credit score distribution continued to account for the lion’s share of delinquencies: 69 percent in 2008 and 66 percent in 2009. Individuals in the top 40 percent of the initial credit score distribution never accounted for more than 15 percent of total dollars in delinquency, even at the height of the mortgage default crisis. As the right panel shows, the exact same pattern is seen for foreclosures, where we use the flag in the credit bureau data for an individual experiencing a foreclosure in the past 24 months.

Our reading of the evidence in Figure 11.8 is that the default crisis was primarily associated with defaults among low credit–score individuals, especially at the beginning of the crisis during the financial sector meltdown.

11.6 Contrasting with Recent Research

In this section, we describe some of the reasons for disagreement in recent research on the source of the mortgage credit boom and bust. We begin with two conceptual points, and then discuss more detailed data issues that lead to different conclusions.

11.6.1 The Extensive versus Intensive Margin of the Rise in Household Debt

One source of disagreement in recent research is based on confusion between the extensive margin and intensive margin of household debt expansion. The analysis in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) was focused uniquely on the extensive margin of credit expansion, or the expansion of credit that allowed households that previously were unable to obtain a mortgage to buy a home. The article does not claim that expansion in mortgage credit for home purchase to marginal borrowers explains the rise in aggregate household debt.

This point is emphasized in our follow-up work: in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014a), we wrote, “let’s recall that households in the United States doubled their debt burden to $14 trillion from 2000 to 2007. As massive as it was, the extension of credit to marginal borrowers alone could not have increased aggregate household debt by such a stunning amount. In 1997, 65% of U.S. households already owned their homes. Many of these homeowners were not marginal borrowers – most of them already had received a mortgage at some point in the past.” Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011) and Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2014b) focused on the rise in aggregate household debt, and these studies show that home equity extraction by all but the top 20 percent of the distribution was the most important factor in explaining the rise in aggregate household debt.

Many of the findings in Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) support the credit supply view of expansion on the extensive margin. Their summary statistics show that low-income ZIP codes saw stronger growth in home-purchase mortgage originated amounts from 2002 to 2006, while households in these ZIP codes saw lower income growth. They also show in the aggregate that the share of mortgages for home purchase by low-income ZIP codes increased from 2002 to 2006.

Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) also show that the growth in average mortgage size conditional on origination is positively correlated with IRS income growth. As we show in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2017), this finding is an artifact of improper calculation of total mortgage size in Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016). More specifically, Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) treat first and second liens as separate mortgages instead of combining them when calculating the total mortgage size used in a home purchase. Second liens are smaller than first liens, and second liens expanded more in low income–growth ZIP codes, which makes it appear as if average mortgage size decreased in low income–growth ZIP codes. Once first and second liens are properly combined, Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2017) show that average mortgage size increased in low credit–score, low income–growth ZIP codes during the mortgage credit boom.

In general, it is crucial to emphasize that the credit supply view of the mortgage boom does not imply that the lowest-income or lowest credit–score individuals were responsible for the aggregate rise in household debt. The aggregate rise in household debt was driven by homeowners borrowing against the rise in home equity, and as already mentioned, this was prevalent in most of the distribution except at the very top. The key finding in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2009) is that credit expanded to marginal households previously unable to obtain credit, and this was unrelated to improvements in income.

11.6.2 Falling House Prices versus Credit Expansion?

A second conceptual point is the assertion in some studies that falling house prices “caused” the mortgage default crisis, and therefore the credit supply view is incorrect. This is a conceptually flawed assertion. A homeowner with positive equity will never default on her mortgage. Instead, she will sell the house, pay off the mortgage, and pocket the equity value of the home. As a result, negative equity is a necessary condition for default. In any hypothesis explaining the mortgage default crisis, a decline in house prices will be necessary to generate a rise in defaults. Put differently, the fact that falling house prices generate a default crisis is almost a tautology: it does not help discern different hypotheses for why the default crisis occurred.

The key question is: what explains the rise and fall in house prices? As already mentioned, a substantial body of evidence shows that the expansion in mortgage credit supply pushed up house prices, and this expansion was unsustainable given that it was not based on fundamental improvements in income. There are also convincing studies showing the role of speculators, investors, and mortgage fraud in explaining the rise and fall in house prices. But any hypothesis for what caused the mortgage default crisis must take a stand on the fundamental cause of the dramatic rise and fall in house prices. Simply stating that house price declines caused mortgage defaults is insufficient.

11.6.3 Using Share of Defaults over Time

The evidence in Figures 11.7 and 11.8 show that default rates and total defaulted amounts were highest for low credit–score individuals during the mortgage default crisis. However, recent research questions this conclusion, asserting that middle and even high credit–score borrowers played a more important role (Adelino, Schoar, and Severino Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016). What explains this disagreement?

The main source of this disagreement is how the basic facts are interpreted. Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) in particular focus on the share of total defaults over time, and they show that the share of total defaults for richer and higher credit–score individuals went up during the mortgage default crisis relative to previous years. There is no disagreement on this basic fact; one can see this also in our Figure 11.8.

The fact that the share of defaults increased for high credit–score individuals is interesting, and perhaps informs us on important questions about the default crisis. However, in our view, this fact does not imply that high credit–score individuals drove the default crisis. Even with a higher share of total defaults in 2008, individuals in the top 40 percent of the credit score distribution had total delinquent debt of only $178 billion. Individuals in the bottom 20 percent of the credit score distribution had $530 billion of delinquent debt in 2008, three times larger.

A focus on the change in the share of defaults over time can lead to faulty conclusions on the source of overall defaults during the crisis. For example, in 2003, the top 20 percent of the credit score distribution made up only 2.3 percent of total defaults. In 2008, their share increased to 3.9 percent of defaults. This rise is a large increase in the share of defaults relative to the baseline in 2003. But in 2008, the top 20 percent had a total amount in default of $59 billion, which is only one-third the amount of defaults by the lowest 20 percent of the credit score distribution in 2003. Defaults in the crisis by the top 20 percent of the credit score distribution were small even relative to defaults of the lowest credit score bin in a normal year. In general, we believe the best way of assessing who drove the default crisis is to look at who made up most of the dollar amount in default during the crisis, not by a comparison of default shares in a crisis versus non-crisis year. It is unambiguous that low credit–score individuals accounted for the lion’s share of defaults during the crisis.

11.6.4 Other Data Issues

Two other data issues help explain some of the disagreements in recent research. First, the use of fraudulently overstated income reported on mortgage applications leads to incorrect conclusions. While Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) confirm that total mortgage origination growth for home purchase is negatively correlated with IRS income growth in a ZIP code from 2002 to 2005, they find a positive correlation between total mortgage origination growth and the growth in income reported on mortgage applications in a ZIP code.

The reason for this finding is that income reported on mortgage applications was fraudulently overstated during the mortgage credit boom, and this fraudulent overstatement was pronounced in ZIP codes with low income growth. The fact that fraudulent overstatement of income was a prominent part of the mortgage credit boom is one of the most rigorously established facts in the literature (Avery et al. Reference Avery, Bhutta, Brevoort and Canner2012; Blackburn and Vermilyea Reference Blackburn and Vermilyea2012; Garmaise Reference Garmaise2015; Jiang, Nelson, and Vytlacil Reference Jiang, Nelson and Vytlacil2014; Mian and Sufi Reference Mian and Sufi2017). We address this issue in more detail in a companion piece (Mian and Sufi Reference Mian and Sufi2017) and we show that researchers should not use mortgage application income in low credit–score ZIP codes as true income. It leads to mistaken conclusions on the nature of the credit supply expansion.

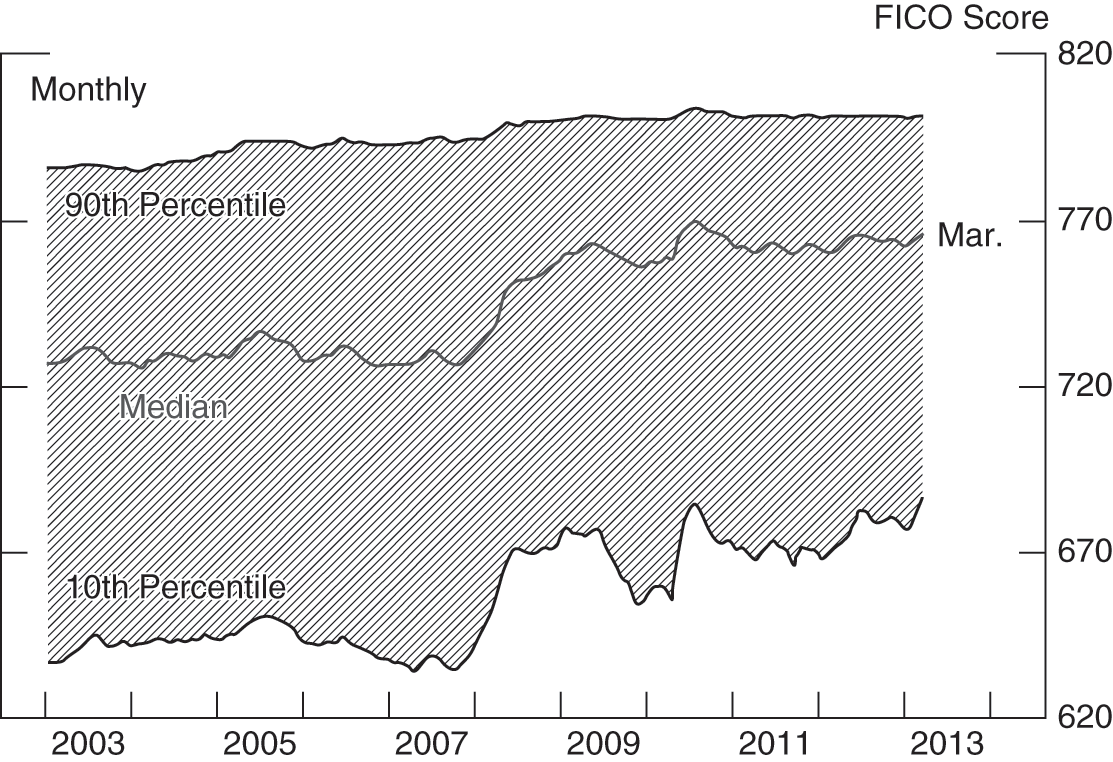

A second data issue is the measurement of credit scores. Our research always sorts individuals or ZIP codes based on their credit score prior to the mortgage credit boom, and then follows the same group over time. We sort based on ex ante credit scores because credit scores become endogenous to the mortgage credit boom from 2002 to 2006. In contrast, many researchers dynamically sort individuals into groups based on their credit score during the boom. For example, Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (Reference Adelino, Schoar and Severino2016) sort individuals into groups based on the credit score at origination on home purchase mortgages in 2006.

Sorting on credit scores during the mortgage credit boom mechanically biases the correlation between credit scores and default rates upward because credit scores increased more for individuals in high house price–growth areas who were borrowing heavily against home equity. As we show in Mian and Sufi (Reference Mian and Sufi2011), low credit–score individuals living in high house price growth areas saw a sharp decline in defaults from 1997 to 2005 (see the middle panel of their figure 5). In that study, we argue lower default rates were due to the ability of homeowners in high house price–growth areas to extract equity to avoid default in case of a negative shock such as unemployment (e.g., Hurst and Stafford Reference Erik and Stafford2004). When house prices crashed, the pattern reverses and default rates increase by far more for the same households that saw the largest drop in default rates during the boom.

Because of lower default rates during the boom, low initial credit–score homeowners in high house price–growth areas saw the largest increase in their credit scores from 2000 to 2006. Table 11.6 shows that the largest increase in credit scores occurred among the lowest 40 percent of the credit score distribution living in high house price–growth areas (the top right four cells). We know from Table 11.5 that these individuals made up the largest share of defaults during the crisis. In other words, conditional on the 2006 credit score, the increase in credit scores from 2000 to 2006 predicts higher defaults during the crisis.

Table 11.6: Change in Credit Scores, by Credit Score and House Price Growth

This table shows the change in the Vantage Score from 2000 to 2006 by 1997 credit score quintile and by house price growth from 2000 to 2007. Each individual is assigned the house price growth from 2000 to 2007 of the ZIP code in which he or she resided in 2000.

| Credit Score Quintile | Change in Vantage Score, 2000 to 2006 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Price Growth Category | |||||

| lt 40% | 40–75% | 75–105% | 105–130% | gt 130% | |

| 1 | 30.1 | 40.0 | 38.6 | 43.1 | 43.9 |

| 2 | 31.2 | 42.2 | 45.1 | 47.6 | 48.5 |

| 3 | 32.1 | 38.7 | 40.5 | 43.4 | 43.4 |

| 4 | 22.7 | 26.3 | 24.7 | 26.8 | 24.6 |

| 5 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 8.1 |

We confirm this result in a regression framework reported in Table 11.7. Using the individual-level Equifax data, we first show that a higher credit score as of 2006 predicts a lower propensity to default during the crisis. However, conditional on the credit score in 2006, an increase in the credit score from 1998 to 2006 is positively related to defaults during the crisis. As column 5 shows, the increase in credit scores from 2002 to 2006 in particular strongly predicts defaults. This shows the endogeneity of credit scores during the mortgage credit boom, and it shows that sorting on credit scores during the boom will mechanically push up the correlation between credit scores and default propensities.

Table 11.7: Increases in Credit Scores during Boom Predicts Default during Bust

This table presents regressions in individual-level credit bureau data of the probability of default during the crisis on credit scores prior to 2007. While the level of the credit score in 2006 is negatively correlated with subsequent defaults, the change in credit scores from 1998 to 2006 is positively related to subsequent defaults.

| (1) Default in 2008 | (2) Default in 2008 | (3) Default in 2009 | (4) Default in 2010 | (5) Default in 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Score, 2006 | −12.527** (0.061) | −13.423** (0.068) | −12.731** (0.069) | −12.153** (0.068) | −12.424** (0.070) |

| ∆ Credit Score, 1998 to 2006 | 2.318** (0.079) | 3.655** (0.084) | 3.981** (0.083) | ||

| ∆ Credit Score, 1998 to 2000 | 2.279** (0.116) | ||||

| ∆ Credit Score, 2000 to 2002 | 3.653** (0.126) | ||||

| ∆ Credit Score, 2002 to 2004 | 4.775** (0.127) | ||||

| ∆ Credit Score, 2004 to 2006 | 5.717** (0.126) | ||||

| Constant | 114.384** (0.534) | 120.476** (0.576) | 114.819** (0.580) | 109.569** (0.577) | 111.899** (0.591) |

| Observations | 245308 | 244299 | 244299 | 244299 | 240502 |

| R2 | 0.213 | 0.216 | 0.176 | 0.161 | 0.165 |

11.7 Conclusion

In their classic history of financial crises, Kindleberger and Aliber (Reference Kindleberger and Aliber2011) provide an axiom: “asset price bubbles depend on the growth in credit.” They show that even classic asset price bubble episodes such as the tulip mania in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century were associated with significant leverage. An established body of economic models shows how changes in leverage can have a causal effect on asset prices (e.g., Allen and Gale Reference Allen and Gale2000; Geanakoplos Reference Geanakoplos2010). We believe that the evidence from the United States during the first decade of the twenty-first century is most consistent with the view that credit expansion played a prominent role in explaining the rise in house prices.

The view in which credit expansion played no independent role in the mortgage debt boom and subsequent default crisis is inconsistent with the evidence. Further, it leads to a mistaken conclusion that we have no understanding of the nature of boom-and-bust episodes.

This not to say we understand everything about the U.S. experience from 2000 to 2010. There are a number of open questions. For example, what was the fundamental driver of the increase in credit supply? The increase in global savings, especially from East Asian and oil-producing countries, is a likely culprit. Levitin and Wachter (Reference Levitin and Wachter2012) make a compelling case that private-label securitization took on a fundamentally different character in the early 2000s. Research by Bruno and Shin (Reference Bruno and Shin2015), Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (Reference Miranda-Agrippino and Rey2015), and Rey (Reference Rey2015) suggests that monetary policy is also an important driver of credit supply shifts. A rise in income inequality in the United States may have helped fuel higher credit availability.

Also, what is the exact interaction between behavioral biases, fraud, and leverage? In one extreme view, the originators of mortgage credit knew that they were feeding an unsustainable bubble, and were preying on both the buyers of homes and the ultimate holders of the mortgage-backed securities. On the other extreme, perhaps the originators of mortgage credit expanded lending because of their own beliefs about house prices. Cheng, Raina, and Xiong (Reference Cheng, Raina and Xiong2014) provide evidence to support the latter view. However, the sheer scale of the fraud by mortgage originators and banks is difficult to resolve with the view that the financial sector was an innocent bystander simply caught up in a bubble (e.g., Griffin and Maturana Reference Griffin and Maturana2016b; Piskorski, Seru, and Witkin Reference Piskorski, Seru and Witkin2015). Regardless of whether lenders had flawed expectations or not, their decision to extend credit was an important driver of the housing boom.

Finally, models in which a credit supply shock drives house prices typically do not take into account the feedback effect of house prices on consumption. While the credit supply view holds that the fundamental shock is an expansion in credit supply, the macroeconomic effects are mainly driven by homeowners borrowing against the rise in home equity. This feedback effect should be present in models, and research is needed to understand exactly why homeowners borrow so aggressively. Flawed expectations formation or other behavioral biases are likely important.

Authors’ Note

This research was supported by funding from the Initiative on Global Markets at Chicago Booth, the Fama-Miller Center at Chicago Booth, and Princeton University. We thank Seongjin Park, Jung Sakong, and Xiao Zhang for excellent research assistance. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of any other institution. We appreciate the comments from many colleagues at various universities. A previous version of this manuscript circulated as: “Household Debt and Defaults from 2000 to 2010: Evidence from Credit Bureau Data.” The appendix is available on our websites at this link: http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/amir.sufi/data-and-appendices/miansufi_creditsupplyviewappendix.pdf. Mian: (609) 258–6718, atif@princeton.edu; Sufi: (773) 702–6148, amir.sufi@chicagobooth.edu.

12.1 Introduction

Real estate is vulnerable to procyclicality, with real estate booms and busts often leading to financial and economic instability.1 The Great Recession in the United States was triggered by the collapse of securitized finance, which had spawned a credit-fueled bubble in residential real estate (Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2012; McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Pavlov and Wachter2009). The bursting of the twin real estate and credit bubbles ultimately crippled the U.S. financial system and the real economy (Levitin, Pavlov, and Wachter Reference Levitin, Pavlov and Wachter2012; Levitin and Wachter Reference Levitin and Wachter2012).

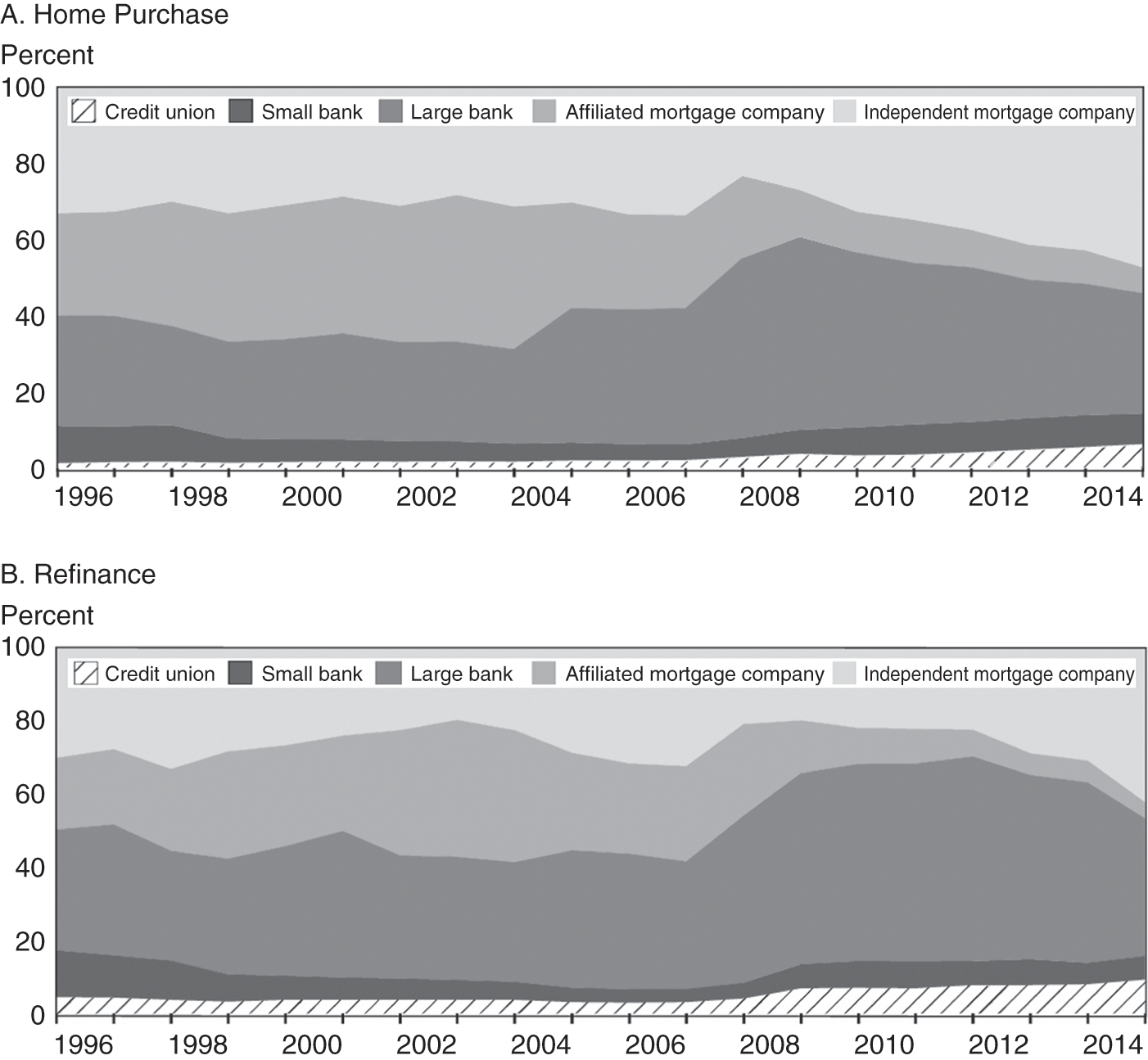

In hindsight, we know that securitization was accompanied by a decline in underwriting standards that exacerbated the subsequent economic downturn and that contractual obligations in the form of representations and warranties did not deter this decline. Through securitization, originators pass virtually all mortgage risk to the market. Thus, in order to align the incentives of originators with those of investors in residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), originators are subject to put-back risk for violations of representations and warranties. The purpose of these contractual obligations is to assure maintenance of underwriting standards.

This chapter examines why representations and warranties failed to accomplish this key requirement for the integrity and sustainability of the securitization process. These provisions in loan sale agreements for RMBS are paradoxical in nature. Representations and warranties did not stop the wave of bad loans from capsizing the U.S. housing market in 2007 and 2008 and the expectation that they would, arguably, worsened the crisis. Yet more recently, liability for the breach of those representations by originators and other securitization participants, along with loan losses themselves, have been linked to bank lenders’ withdrawal from the market and overly tight lending standards, which slowed the recovery process. Post-crisis, lenders’ fears over put-back exposure appear to have contributed to a contraction in lending to creditworthy borrowers.2 This contraction has coincided with the return of thinly capitalized nonbank lenders, who have little capital at risk for future mortgage repurchase claims.

If both are true, then the representations and warranties in securitization documents through 2008 were simultaneously too weak and too harsh, engendering procyclicality.3 During the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, these representations gave investors false assurance that mortgage loans were being properly underwritten, contributing to overinvestment in underpriced MBS. Moreover, there was virtually no enforcement of those provisions during the bubble, which exaggerated their cyclical effects. Only later, after the harm was done, did the pendulum swing to excess enforcement and fear of penalties, which encouraged undue restrictiveness in the origination of mortgages and hampered the economic recovery.

Is this paradoxical outcome due to surprise that these agreements would ever be enforced and surprise about how they were enforced; or due to the unforeseen events that made these agreements actionable; or due to misaligned incentives that led agents to knowingly ignore these contractual obligations? Or to some combination of these differing interpretations of ignorance or malfeasance? More critically, going forward, for the integrity of the securitization process, can representations and warranties be reformed to buttress the integrity of the securitization process, or are there intrinsic limitations on the use of contractual terms to assure this outcome?

This chapter proceeds as follows. Part 2 provides an overview, describing the intended role of representations and warranties in deterring loose underwriting and providing compensation for breach, how these contractual provisions failed to halt the deterioration in underwriting during the credit bubble, and the efforts to enforce these provisions following the 2008 crisis. In Part 3, we survey the market responses to put-back litigation, including contraction of credit by bank lenders and the concomitant surge in market share by more lightly regulated nonbank lenders, and propose reforms. In particular, we contend that representations and warranties will not have teeth unless they are accompanied by countercyclical provisioning and capital standards. Part 4 concludes.

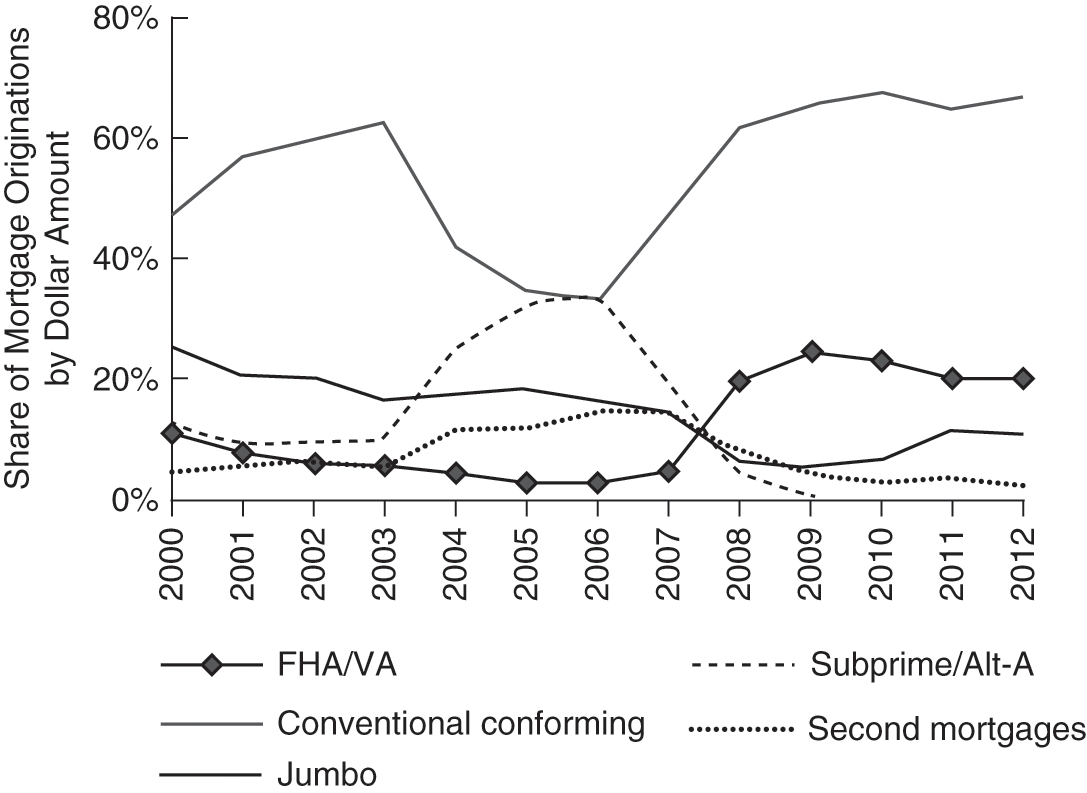

12.2 Historical Background and Overview of Recent Mortgage Put-Back Liability

The current controversy over mortgage put-backs emanates from the shift of U.S. housing finance from a bank-based system to a capital-markets system over the past 50 years. Fifty years ago, mortgage originators usually held loans in portfolio. But that all changed in the 1970s with the invention of MBS,4 which gave mortgage lenders the ability to move newly originated mortgages off their balance sheets by bundling those loans into bonds sold to private investors. Over time, securitization became the predominant means of mortgage finance and three securitization channels emerged: Ginnie Mae for FHA-insured and VA mortgages, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for other conforming mortgages (also known as agency mortgages), and the private-label (Wall Street) market for nonconforming mortgages (most notably jumbo loans and subprime and Alt-A mortgages).5 Securitization offers benefits to depository institutions by solving the term-mismatch problem arising because bank liabilities (in the form of demand deposits) are considerably more liquid than their long-term mortgage assets (Diamond Reference Diamond2007).