Introduction The bonfire of the humanities?

A spectre is haunting our time: the spectre of the short term.

We live in a moment of accelerating crisis that is characterised by the shortage of long-term thinking. Even as rising sea-levels threaten low-lying communities and coastal regions, the world’s cities stockpile waste, and human actions poison the oceans, earth, and groundwater for future generations. We face rising economic inequality within nations even as inequalities between countries abate while international hierarchies revert to conditions not seen since the late eighteenth century, when China last dominated the global economy. Where, we might ask, is safety, where is freedom? What place will our children call home? There is no public office of the long term that you can call for answers about who, if anyone, is preparing to respond to these epochal changes. Instead, almost every aspect of human life is plotted and judged, packaged and paid for, on time-scales of a few months or years. There are few opportunities to shake those projects loose from their short-term moorings. It can hardly seem worth while to raise questions of the long term at all.

In the age of the permanent campaign, politicians plan only as far as their next bid for election. They invoke children and grandchildren in public speeches, but electoral cycles of two to seven years determine which issues prevail. The result is less money for crumbling infrastructure and schools and more for any initiative that promises jobs right now. The same short horizons govern the way most corporate boards organise their futures. Quarterly cycles mean that executives have to show profit on a regular basis.1 Long-term investments in human resources disappear from the balance sheet, and so they are cut. International institutions, humanitarian bodies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) must follow the same logic and adapt their programmes to annual or at most triennial constraints. No one, it seems, from bureaucrats to board members, or voters and recipients of international aid, can escape the ever-present threat of short-termism.

There are individuals who buck the trend, of course. In 1998, the Californian cyber-utopian Stewart Brand created the Long Now Foundation to promote consciousness of broader spans of time. ‘Civilization is revving itself into a pathologically short attention span’, he wrote: ‘Some sort of balancing corrective to the short-sightedness is needed – some mechanism or myth that encourages the long view and the taking of long-term responsibility, where “the long term” is measured at least in centuries.’ Brand’s charismatic solution to the problem of short-termism is the Clock of the Long Now, a mechanism operating on a computational span of 10,000 years designed precisely to measure time in centuries, even millennia.2

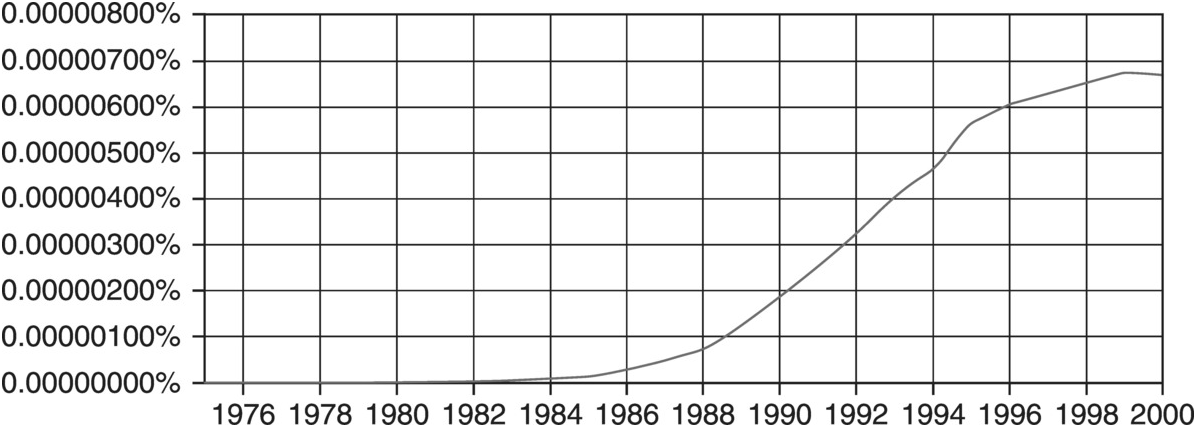

But the lack of long-range perspective in our culture remains. The disease even has a name – ‘short-termism’. Short-termism has many practitioners but few defenders. It is now so deeply ingrained in our institutions that it has become a habit – frequently followed but rarely justified, much complained about but not often diagnosed. It was only given a name, at least in English, in the 1980s, after which usage sky-rocketed significantly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Usage of ‘short-termism’, c. 1975–2000

The most ambitious diagnosis of short-termism to date came from the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations. In October 2013, a blue-ribbon panel chaired by Pascal Lamy, former Director-General of the World Trade Organization (WTO), issued its report, Now for the Long Term, ‘focusing on the increasing short-termism of modern politics and our collective inability to break the gridlock which undermines attempts to address the biggest challenges that will shape our future’. Though the tone of the report was hardly upbeat, its thrust was forward-looking and future-oriented. Its motto might have been the words quoted in its introduction and attributed to former French premier Pierre Mendès France: gouverner, c’est prévoir – to govern is to foresee.3

Imagining the long term as an alternative to the short term may not be so difficult, but putting long-termism into practice may be harder to achieve. When institutions or individuals want to peer into the future, there is a dearth of knowledge about how to go about this task. Instead of facts, we routinely resort to theories. We have been told, for instance, that there was an end to history and that the world is hot, flat, and crowded.4 We have read that all human events are reducible to models derived from physics, translated by economics or political science, or explained by a theory of evolution that looks back to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Editorials apply economic models to sumo wrestlers and palaeolithic anthropology to customs of dating.5 These lessons are repeated on the news, and their proponents are elevated to the status of public intellectuals. Their rules seem to point to unchanging levers that govern our world. But they do little to explain the shifting hierarchy of economies or the changes in gender identity and reconfigurations of banking witnessed in our own time. Only in rare conversations does anyone notice that there are long-term changes flowing around us, ones that are relevant and possible to see. The world around us is clearly one of change, irreducible to models. Who is trained to steadily wait upon and translate them for others, these vibrations of deeper time?

Even those who have assigned themselves the task of inspecting the future typically peer only shortsightedly into the past. Stewart Brand’s Clock of the Long Now points 10,000 years ahead but looks barely a century backwards. The Martin Commission searched for evidence for various ‘megatrends’ – among them, population growth, shifts in migration, employment, inequality, sustainability, and health care – but the Commission included no historians to tell them how much these trends had changed over a lifespan, or the truly long-term of centuries or millennia. In fact, few of the examples the Commission cited in Now for the Long Term came from before the late 1940s. Most of the evidence entertained by these self-proclaimed futurologists came from the last thirty years, even though the relevant section of the report carried the title, ‘Looking Back to Look Forward’. Such historical myopia is itself a symptom of the short-termism they are trying to overcome.

Indeed, the world around us is hungry for long-term thinking. In political science departments and over dinner tables, citizens around the world complain about political stagnation and the limits of two-party systems. A lack of serious alternatives to laissez-faire capitalism is the hallmark of contemporary world governance from the World Bank to the WTO. Currencies, nations, and sea-levels fall and rise. Even the professions in advanced economies that garnered the most secure jobs a generation ago are no longer stable. What sort of an education prepares individuals for so volatile a run through the journey of life? How does a young person come to learn not only to listen and to communicate, but also to judge institutions, to see which technologies hold promise and which are doomed to fail, to think fluidly about state and market and the connections between both? And how can they do so with an eye to where we have come from, as well as where we are going to?

Thinking about the past in order to see the future is not actually so difficult. Most of us become aware of change first in the family, as we regard the omnipresent tensions between one generation and the next. In even these familial exchanges, we look backwards in order to see the future. Nimble people, whether activists or entrepreneurs, likewise depend on an instinctual sense of change from past to present to future as they navigate through their day-to-day activities. Noticing a major shift in the economy before one’s contemporaries may result in the building of fortunes, as is the case for the real estate speculator who notices rich people moving to a former ghetto before other developers. Noticing a shift in politics, an amassing of unprecedented power by corporations and the repeal of earlier legislation, is what precipitated a movement like Occupy Wall Street. Regardless of age or security of income, we are all in the business of making sense of a changing world. In all cases, understanding the nexus of past and future is crucial to acting upon what comes next.

But who writes about these changes as long-term developments? Who nourishes those looking for brighter futures with the material from our collective past? Centuries and epochs are often mysteries too deep and wide for journalists to concern themselves with. Only in rare conversations does anyone notice that there are continuities that are relevant and possible to see. Who is trained to wait steadily upon these vibrations of deeper time and then translate them for others?

Universities have a special claim as venues for thinking on longer time scales. Historically, universities have been among the most resilient, enduring, and long-lasting institutions humans have created. Nalanda University in Bihar, India, was founded over 1500 years ago as a Buddhist institution and is now being revived again as a seat of learning. The great European foundations of Bologna (1088), Paris (c. 1150), Oxford (1167), Cambridge (1209), Salamanca (1218), Toulouse (1229), and Heidelberg (1386), to name only a few, date back to the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries, and there were universities in mid sixteenth-century Peru and Mexico decades before Harvard or Yale was chartered. By contrast, the average half-life of a twentieth-century business corporation has been calculated at seventy-five years: there may be only two companies in the world that can compare with most universities for longevity.6

Universities, along with religious institutions, are the carriers of traditions, the guardians of deep knowledge. They should be the centres of innovation where research takes place without regard to profit or immediate application.7 Precisely that relative disinterestedness has given the university particular room to ponder long-term questions using long-term resources. As the vice-chancellor of the oldest university in Oceania, the University of Sydney (1850), has noted, universities remain ‘the one player capable of making long-term, infrastructure-intensive research investments … Business generally seeks return on investment over a period of a few years. If universities take a similar approach, there will simply be no other entities globally capable of supporting research on 20-, 30-, or 50-year time horizons.’8

Yet the peculiar capacity of the university to foster disinterested inquiries into the long term may be as endangered as long-term thinking itself. For most of the history of universities, the responsibility for passing on tradition and subjecting it to critical examination has been borne by the humanities.9 These subjects now include the study of languages, literature, art, music, philosophy, and history, but in their original conception extended to all non-professional subjects, including logic and rhetoric, but excluding law, medicine, and theology. Their educational purpose was precisely not to be instrumental: to examine theories and instances, to pose questions and the means of their solution, but not to propose practical objectives or strategies. As the medieval university mutated into the modern research university, and as private foundations become subject to public control and funding, the goals of the humanities were increasingly tested and contested. For at least the last century, wherever the humanities have been taught or studied there has been debate about their ‘relevance’ and their ‘value’. Crucial to the defence of the humanities has been their mission to transmit questions about value – and to question values – over hundreds, even thousands, of years. Any search for antidotes to short-termism must begin with them.

Yet everywhere we turn the humanities are said to be in ‘crisis’: more specifically, the former president of the American Historical Association, Lynn Hunt, has recently argued that the field of ‘history is in crisis and not just one of university budgets’.10 There is nothing new in this: the advantage of a historical perspective is knowing that the humanities have been in recurrent crisis for the last fifty years at least. The threats have varied from country to country and from decade to decade but some of the enemies are consistent. The humanities can appear ‘soft’ and indistinct in their findings compared to the so-called ‘hard’ sciences. They can seem to be a luxury, even an indulgence, in contrast to disciplines oriented towards professional careers, like economics or law. They rarely compete in the push to recruit high-profit relationships with software, engineering, and pharmaceutical clientele. And they can be vulnerable to new technologies that might render the humanities’ distinctive methods, such as close reading of texts, an appreciation for abstract values, and the promotion of critical thinking over instrumental reasoning jejune. The humanities are incidental (not instrumental), obsolescent (not effervescent), increasingly vulnerable (not technologically adaptable) – or so their enemies and sceptics would have us believe.11

The crisis of the university has become acute for several reasons. The accumulation and dissemination of knowledge through teaching and publishing is undergoing changes more profound than at any point in the last five hundred years. In many parts of the world, but especially in North America, parents and students have inherited a university retooled into a specialised engine of expertise, often dominated by the star disciplines of physics, economics, and neuroscience, designed to manufacture articles at record numbers, and often insensitive to other traditions of learning. The latest ‘crisis of the humanities’ has been much discussed and its causes broadly debated. Enrolments in humanities courses have apparently declined from historic highs. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) seemed to portend the extinction of small-group teaching and the intimate process of interaction between teachers and students. The shifting boundaries between humanistic and scientific disciplines can make this manner of engaging the humanities seem quaint or superfluous. Squeezes on public revenues and private endowments create pressures from outside universities to deliver value and from inside them to demonstrate viability. For teachers of the humanities, battling these challenges from within and from without can feel like a struggle against the many-headed Hydra: Herculean – and therefore heroic – but unremitting, because every victory brings with it a new adversary.

Administrators, academics, and students alike struggle to face all these challenges at once. They must strive to find a way forward that will preserve the distinctive virtues of the university – and of the humanities and historical social sciences within them. Importantly, they need experts who can look past the parochial concerns of disciplines too attached to client funding, the next business cycle, or the next election. Indeed, in a crisis of short-termism, our world needs somewhere to turn to for information about the relationship between past and future. Our argument is that History – the discipline and its subject-matter – can be just the arbiter we need at this critical time.

Any broader public looking for solutions to short-termism in the History departments of most universities might have been quite disappointed, at least until very recently. As we document in later chapters, historians once told arching stories of scale but, nearly forty years ago, many if not most of them stopped doing so. For two generations, between about 1975 and 2005, they conducted most of their studies on biological time-spans of between five and fifty years, approximating the length of a mature human life. The compression of time in historical work can be illustrated bluntly by the range covered in doctoral dissertations conducted in the United States, a country which adopted the German model of doctoral education early and then produced history doctorates on a world-beating scale. In 1900, the average number of years covered in doctoral dissertations in history in the United States was about seventy-five years; by 1975, it was closer to thirty. Command of archives; total control of a ballooning historiography; and an imperative to reconstruct and analyse in ever-finer detail: all these had become the hallmarks of historical professionalism. Later in the book, we will document why and how this concentration – some might say, contraction – of time took place. For the moment, it is enough to note that short-termism had become an academic pursuit as well as a public problem in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

It was during this period, we argue, that professional historians ceded the task of synthesising historical knowledge to unaccredited writers and simultaneously lost whatever influence they might once have had over policy to colleagues in the social sciences, most spectacularly to the economists. The gulf between academic and non-academic history widened. After 2000 years, the ancient goal for history to be the guide to public life had collapsed. With the ‘telescoping of historical time … the discipline of history, in a peculiar way, ceased to be historical’.12 History departments lay increasingly exposed to new and unsettling challenges: the recurrent crises of the humanities marked by waning enrolments; ever more invasive demands from administrators and their political paymasters to demonstrate ‘impact’; and internal crises of confidence about their relevance amid adjacent disciplines with swelling classrooms, greater visibility, and more obvious influence in shaping public opinion.

But there are now signs that the long term and the long range are returning. The scope of doctoral dissertations in history is already widening. Professional historians are again writing monographs covering periods of 200 to 2000 years or more. And there is now an expanding universe of historical horizons, from the ‘deep history’ of the human past, stretching over 40,000 years, to ‘big history’ going back to the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago. Across many fields of history, big is definitely back.13 The return of the longue durée is how we describe the extension of historians’ time-scales we both diagnose and recommend in this book.14 In the last decade, across the university, the rise of big data and problems such as long-term climate change, governance, and inequality are causing a return to questions about how the past develops over centuries and millennia, and what this can tell us about our survival and flourishing in the future. This has brought a new sense of responsibility, as well as urgency, to the work of historians who ‘should recognize that how they tell the story of the past shapes how the present understands its potential, and is thus an intervention in the future of the world’, as one practitioner of history’s public future has noted.15

The form and epistemology of these studies is not new. The longue durée as a term of historical art was the invention of the great French historian Fernand Braudel just over fifty years ago, in 1958.16 As a temporal horizon for research and writing the longue durée largely disappeared for a generation before coming back into view in recent years. As we hope to suggest, the reasons for its retreat were sociological as much as intellectual; the motivations for its return are both political and technological. Yet the revenant longue durée is not identical to its original incarnation: as the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu classically noted, ‘returns to past styles are never “the same thing” since they are separated from what they return to by a negative reference to something which was itself the negation of it (or the negation of the negation)’.17 The new longue durée has emerged within a very different ecosystem of intellectual alternatives. It possesses a dynamism and flexibility earlier versions did not have. It has a new relationship to the abounding sources of big data available in our time – data ecological, governmental, economic, and cultural in nature, much of it newly available to the lens of digital analysis. As a result of this increased reserve of evidence, the new longue durée also has greater critical potential, for historians, for other social scientists, for policy-makers, and for the public.

The origins of this new longue durée may lie in the past but it is now very much oriented towards the future. In this sense, it does mark a return to some of the foundations of historical thinking, in the West and in other parts of the world. Until history became professionalised as an academic discipline, with departments, journals, accrediting associations, and all the other formal trappings of a profession, its mission had been primarily educative, even reformative. History explained communities to themselves. It helped rulers to orient their exercise of power and in turn advised their advisors how to influence their superiors. And it provided citizens more generally with the coordinates by which they could understand the present and direct their actions towards the future. The mission for history as a guide to life never entirely lapsed. Increasing professionalism, and the explosion of scholarly publishing by historians within universities, obscured and at times occluded its purpose. But now it is returning along with the longue durée and the expansion of possibilities – for new research and novel public engagement – that accompanies it.

We have organised this short book about the long term into two halves, each of two chapters. The first half maps the rise and fall of long-term thinking among historians; the second, its return and potential future as a critical human science. Chapter 1 traces the fortunes of two trends in historical writing and thinking over a longue durée of centuries and then a shorter span of decades. The initial trend is history’s purpose as a guide to action in the present, using the resources of the past, to imagine alternative possibilities in the future. The other tendency is the more recent genesis of an explicit history of the longue durée, particularly in the work of the highly influential group of French historians associated in the twentieth century with the journal Annales. Pre-eminent among them was Fernand Braudel, the greatest proponent of his own peculiar but enduring conception of what the longue durée meant, in terms of time, movement, human agency (or the lack of it), and human interaction with the physical environment and the structural cycles of economics and politics. Building on earlier models of the longue durée, in this chapter, we set forward three approaches that history offers to those in need of a future: a sense of destiny and free will, counterfactual thinking, and thinking about utopias. Those freedoms of history, as we shall show in the chapters ahead, set aside historical thinking from the natural-law models of evolutionary anthropologists, economists, and other arbiters of our society. They are a crucial remedy for a society paralysed by short-term thinking, because these future-oriented tools of history open up new patterns of imagination with which to understand possible futures.

Almost as soon as the longue durée was named, it began to dissipate, as we show in Chapter 2. From the 1970s to the early twenty-first century, historians across the world began to focus on shorter time-scales. Their motivations were various. Some turned to the command of archives in order the better to fulfil the requirements of professionalisation; others to experiment with theories imported from neighbouring disciplines; still others, because professionalisation and theory offered a safe zone for writing out of their political commitments to radical causes that coincided with contemporary movements: in the United States especially, the Civil Rights movement, anti-war protest, or feminism. Out of these various desires, a new kind of history was born, one that concentrated on the ‘micro-history’ of exceptional individuals, seemingly inexplicable events, or significant conjunctures.

Micro-history was not invented to kill historical relevance but, as we shall see, even historians are haunted by the law of unintended consequences. Dedicated to the cause of testing and debunking larger theories about the nature of time and agency, historians in the English-speaking world who adopted the techniques of micro-history often concentrated upon writing for readers or communities only just finding their political voices. In the process, these micro-historians found themselves bound up with another larger contemporary force in intellectual life: the inward turn of academics towards an ever greater specialisation of knowledge. Still passionate about reform within their activist cells, micro-historians were increasingly rare in conversations about the old ambition of the university to be a guide to public life and possible futures. They were not the only ones. What have been called ‘grand narratives’ – big structures, large processes, and huge comparisons – were becoming increasingly unfashionable, and not just among historians. Big-picture thinking was widely perceived to be in retreat. Meanwhile, short-termism was on the rise.

One consequence of the retreat of historians from the public sphere was that institutions were taken over by other scholars, whose views of the past were determined less by historical data and more by universal models. Notably, this meant the rising profile of economists. As we show in Chapter 3, economists were everywhere – advising policies on the Left, advising policies on the Right; arbitrating grand debates in world government; even talking about the heritage of our hunter-gatherer ancestors and how their economic rationality determined our present and our future. In at least three spheres – discussions of climate, discussions of world government, and discussions of inequality – economists’ universalising models came to dominate conversations about the future. At the end of Chapter 3, we set out the reasons that these views of human nature as static, not historical, are limiting. We outline an alternative approach to the future, and we recommend three modes of thinking about a future that we think good history does well: it looks at processes that take a long time to unfold; it engages false myths about the future and talks about where the data come from; and it looks to many different kinds and sources of data for multiple perspectives on how past and future were and may yet be experienced by a variety of different actors.

We partially explain what is replacing climate apocalypticism and economic predestination in Chapter 4, where we argue that short-term thinking is being challenged by the information technology of our time: the explosion of big data and the means now available to make sense of it all. Here we highlight the ways that scholars, businesses, activists, and historians are using new datasets to aggregate information about the history of inequality and the climate and to project new possible futures. We foreground the particular tools, many of them designed by historians, which are enhancing these datasets and drawing out qualitative models of changing thought over time. We show that this new data for thinking about the past and the future is rapidly outpacing the old analytics of economics, whose indicators were developed between the 1930s and the 1950s to measure the consumption and employment habits of people who lived very differently than we will in the twenty-first century. In coming decades, information scientists, environmentalists, and even financial analysts will increasingly need to think about when their data came from if they want to peer into the future. This change in the life of data may determine a major shift for the university of the future, where historical thinkers will have an increasingly important role to play as the arbiters of big data.

Our Conclusion ends where we started, with the problem of who in our society is responsible for constructing and interpreting the big picture. We are writing at a moment of the destabilisation of nations and currencies, on the cusp of a chain of environmental events that will change our way of life, at a time when questions of inequality trouble political and economic systems around the globe. On the basis of when we write, we recommend to our readers and to our fellow-historians the cause of what we call the public future: we must, all of us, engage the big picture, and do so together, a task that we believe requires us to look backwards as well as ahead.

The sword of history has two edges, one that cuts open new possibilities in the future, and one that cuts through the noise, contradictions, and lies of the past. In the Conclusion, we will claim that history offers three further indispensable means for looking at the past, which have more to do with history’s power to sort truth from falsehood when we speak about our past and present situation. This sorting out of truth is part of the legacy of micro-historical examination, but it pertains equally to problems of big data; in both cases, historians have become adept at examining the basis of claims. History’s power to liberate, we argue, ultimately lies in explaining where things came from, tacking between big processes and small events to see the whole picture, and reducing a lot of information to a small and shareable version. We recommend these methods to a society plagued by false ideas about the past and how it limits our collective hopes for the future.

There is never a problem with short-term thinking until short-termism predominates in a crisis. By implication, never before now has it been so vital that we all become experts on the long-term view, that we return to the longue durée. Renewing the connection between past and future, and using the past to think critically about what is to come, are the tools that we need now. Historians are those best able to supply them.