Book contents

- Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval England

- Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval England

- Copyright page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations, Quotations and References

- Chapter 1 Prologue

- Chapter 2 ‘Hele alle maner of schabbis’

- Chapter 3 ‘Who by prudence Rule him shal’

- Chapter 4 ‘Þe leef torned’

- Chapter 5 ‘Rede … and ʒe may se’

- Chapter 6 ‘This is the copy’

- Chapter 7 Conclusions

- Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- General Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 May 2022

- Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval England

- Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval England

- Copyright page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations, Quotations and References

- Chapter 1 Prologue

- Chapter 2 ‘Hele alle maner of schabbis’

- Chapter 3 ‘Who by prudence Rule him shal’

- Chapter 4 ‘Þe leef torned’

- Chapter 5 ‘Rede … and ʒe may se’

- Chapter 6 ‘This is the copy’

- Chapter 7 Conclusions

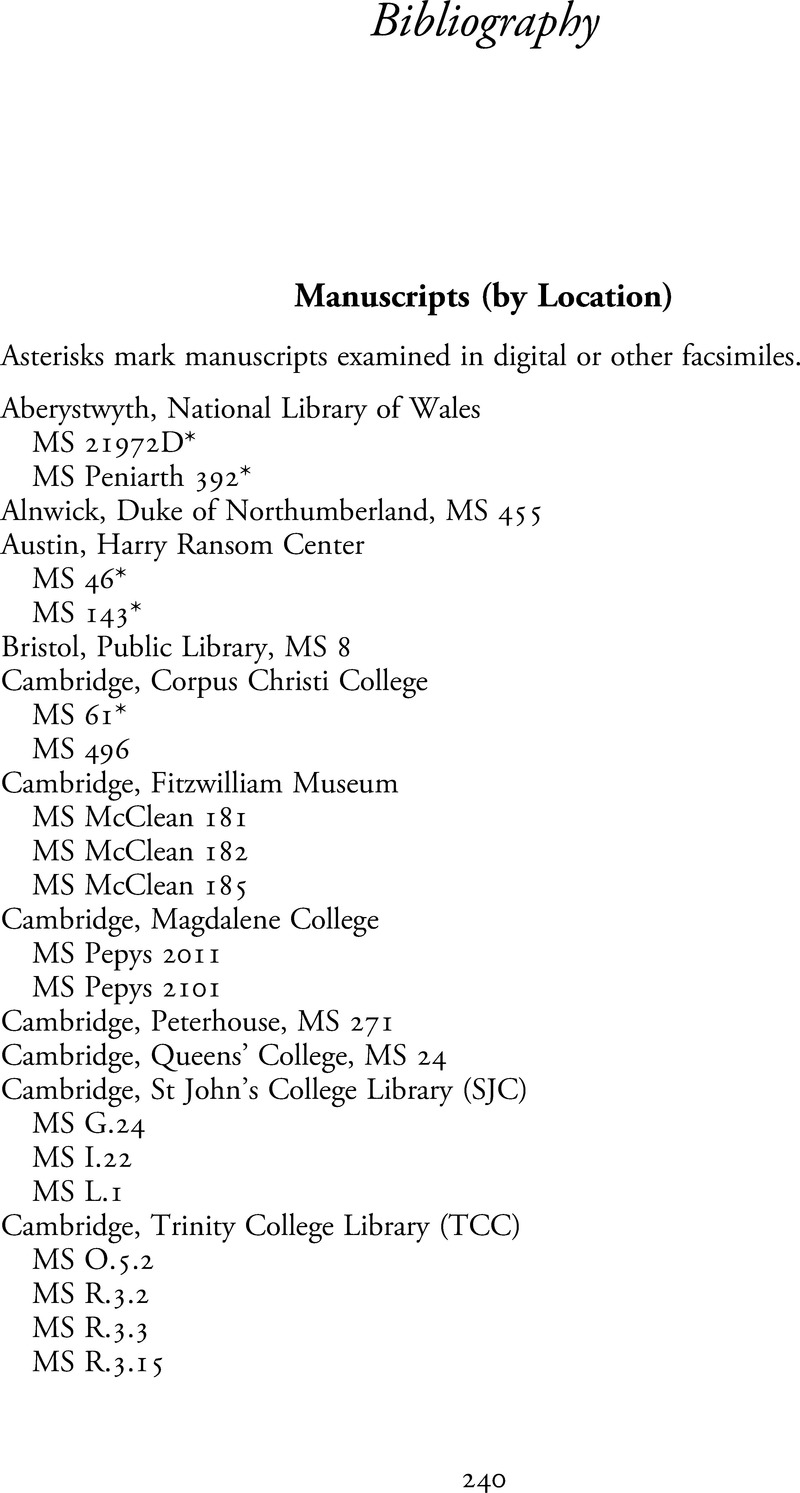

- Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- General Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Immaterial Texts in Late Medieval EnglandMaking English Literary Manuscripts, 1400–1500, pp. 240 - 273Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022