Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Kropotkin and the development of the theory of anarchist communism

- Part II Kropotkin and the development of anarchist ideas of revolutionary action by individuals and small groups (1872–1886)

- 3 Revolutionary action and the emergent anarchist movement of the seventies

- 4 Propaganda by deed: the development of the idea

- 5 Kropotkin and propaganda by deed

- 6 Kropotkin and acts of revolt

- 7 The Congress of London 1881 and ‘The Spirit of Revolt’

- 8 The trial of Lyon 1883 and response to persecution

- Part III Kropotkin and the development of anarchist views of collective revolutionary action (1872–1886)

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

7 - The Congress of London 1881 and ‘The Spirit of Revolt’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Kropotkin and the development of the theory of anarchist communism

- Part II Kropotkin and the development of anarchist ideas of revolutionary action by individuals and small groups (1872–1886)

- 3 Revolutionary action and the emergent anarchist movement of the seventies

- 4 Propaganda by deed: the development of the idea

- 5 Kropotkin and propaganda by deed

- 6 Kropotkin and acts of revolt

- 7 The Congress of London 1881 and ‘The Spirit of Revolt’

- 8 The trial of Lyon 1883 and response to persecution

- Part III Kropotkin and the development of anarchist views of collective revolutionary action (1872–1886)

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The object of convoking the Congress of London had been to revive the International which had languished in the repressive atmosphere following the fall of the commune and the quarrels that had developed amongst the internationalists themselves. The proposal for the Congress came from the Bureau Fédéral de L' Union Révolutionnaire Belge. Unfortunately, the very fact that the initiative came from Belgium may have generated some misgivings because of the abortive efforts of the Parti Socialiste Beige (PSB) to unite the socialist movement there. Certainly from the beginning, as Kropotkin's correspondence with his friends suggests, there was an atmosphere of suspicion and tension in anarchist circles about the proposed Congress. Indeed at the outset the Spanish Federation, even though agreeing to participate, had complained about the proposal to revive the IWA arguing indignantly that it still existed in Spain and elsewhere.

In fact, Kropotkin's assertion that the Congress might be disastrous for the movement proved distressingly near the truth. Although the marxist and blanquist authoritarian influences which Kropotkin had feared most do not seem to have materialised, there can be little doubt that the sinister influence of Serraux did a great deal of damage by fostering a near hysterical obsession with violence. At the same time, the delegates, who in their anxiety to avoid any taint of authoritarianism seemed unable to decide whether they really wanted an organisation or not, set up a corresponding bureau which had no clear role except to help the groups keep in touch with one another.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

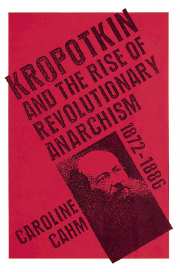

- KropotkinAnd the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism, 1872-1886, pp. 152 - 177Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1989