Book contents

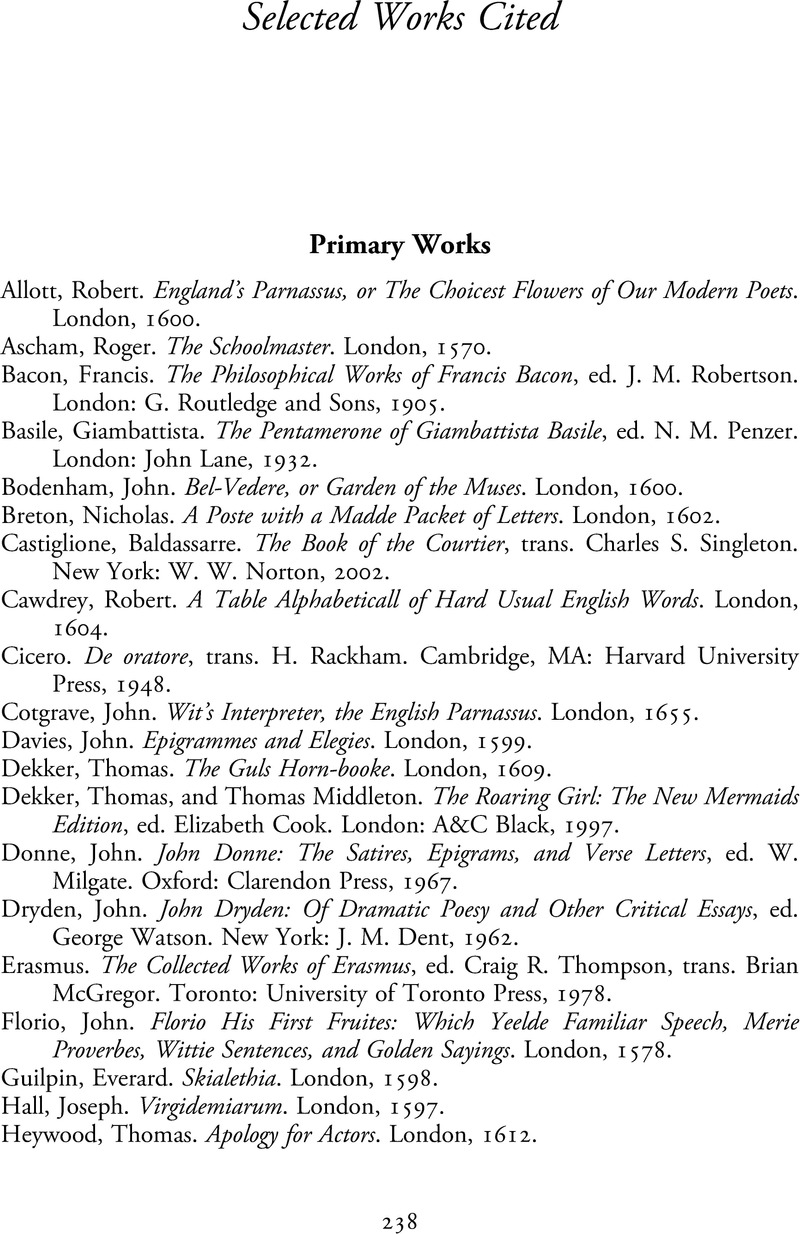

Selected Works Cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 August 2022

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Pursuit of Style in Early Modern DramaForms of Talk on the London Stage, pp. 238 - 250Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022