Book contents

- Schumann’s Music and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Fiction

- Schumann’s Music and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Fiction

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Music examples

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Chrysalis, 1827–1834

- 2 Notions of resonance and expression

- 3 A musical carnival, 1834–1837

- 4 Form, content and conception

- 5 Dream images, 1837

- 6 ‘In possession of the secret’, 1836–1838

- 7 New worlds, 1838

- 8 Associations and expressiveness in Schumann’s ‘Hoffmann works’

- 9 Antimatter, 1839–1840

- 10 ‘The closed book’

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

- Schumann’s Music and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Fiction

- Schumann’s Music and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Fiction

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Music examples

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Chrysalis, 1827–1834

- 2 Notions of resonance and expression

- 3 A musical carnival, 1834–1837

- 4 Form, content and conception

- 5 Dream images, 1837

- 6 ‘In possession of the secret’, 1836–1838

- 7 New worlds, 1838

- 8 Associations and expressiveness in Schumann’s ‘Hoffmann works’

- 9 Antimatter, 1839–1840

- 10 ‘The closed book’

- Appendices

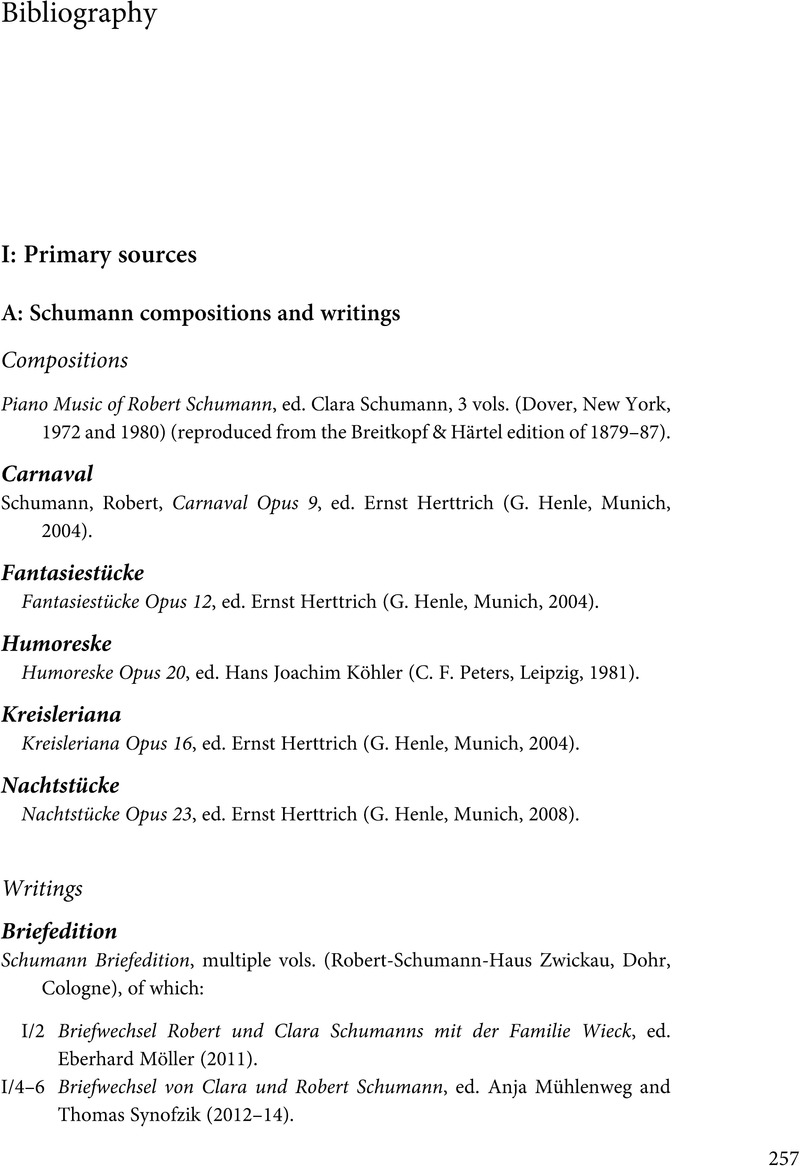

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Schumann's Music and E. T. A. Hoffmann's Fiction , pp. 257 - 274Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016