1 - The word οἰκέτης in late antiquity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2011

Summary

The word οἰκέτης is, along with δοῦλος, one of the two most common terms for slave in late antique Greek (for the early history of the word, see Gschnitzer 1976, 20–1, 71). It is effectively synonymous with δοῦλος, and authors regularly use the two as exact equivalents. The primary distinction is that δοῦλος lends itself more readily to abstract usages, whereas οἰκέτης is a highly concrete, situational term. So, for instance, δουλεία is the primary word for the abstract quality of slavery, whereas the equivalent οἰκετεία is virtually never used (for a rare example, see Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae, 8.6.3). When Libanius, for example, wants to claim that slavery is a peaceful condition that allows the slave to sleep at night without the worries of a free man, he uses δουλεία for the condition, οἰκέτης for the slave who is sleeping (Progymnasmata 9.6.16: Οὐδὲν τοσοῦτον ἡ δουλεία. ὁ μέν γε οἰκέτης καθεύδει ῥᾳθύμως ταῖς τοῦ δεσπότου φροντίσι τρεφόμενος…). In the discussion that follows, I will try to support four claims about the word οἰκέτης in the social idiom of late antique Greek. First, the term οἰκέτης is an equivalent of δοῦλος and ἀνδράποδον. Second, οἰκέτης implies unfree legal status. Third, the οἰκέτης was a chattel slave, not a servant. Fourth, the word οἰκέτης is not equivalent to “domestic slave.” After this discussion I will consider objections to the view that οἰκέτης should be exclusively indicative of slave status.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

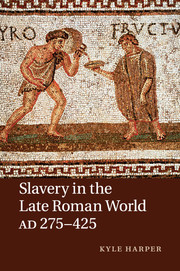

- Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425 , pp. 513 - 518Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011