Among the extensive collection of jewellery in the Victoria and Albert Museum, there is a beautiful but macabre object: a pair of earrings made from the stuffed heads of two hummingbirds (Figure 1.1). Mounted on gold bases, the little birds stare blankly at the viewer through red glass eyes. Their delicate feathers glisten red, green and yellow and their tiny, gold-embossed beaks probe the air. The museum’s catalogue states that the earrings were manufactured around 1865 by Harry Emanuel, a London jeweller who worked in both feathers and ivory. They belonged to Mrs Sidney Matilda Adams (1806–86) and were donated to the museum by her great-great-granddaughter, Katharine Mortimer.Footnote 1

Figure 1.1 Hummingbird earrings, c.1865.

The sight of two dead birds on women’s jewellery is shocking to a modern viewer and strikes us as bizarre, ghoulish and repulsive. In the nineteenth century, however, the practice of wearing birds’ corpses on earrings, dresses and, most commonly, hats was regarded as the height of fashion. From the 1860s until the First World War, women adorned themselves with the plumage of hummingbirds, egrets and other attractive birds, competing with one another to achieve the most elaborate creations. One lady, attending a drawing room at Dublin Castle in 1878, wore a dress ‘trimmed with the skins of 300 robins’.Footnote 2 Across the Atlantic, a correspondent of the American magazine Forest and Stream spotted ‘on 700 hats 542 birds’ walking down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1886, ‘the common tern and quail being the most frequent’.Footnote 3 In such a setting, a pair of shimmering hummingbird earrings would certainly not have seemed out of place.

This chapter examines the craze for birds’ plumage in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and assesses its severe environmental impact. A product of new manufacturing techniques, changing tastes and expanding commercial networks, the plumage trade was big business. It provided stylish headgear for women in Europe and the USA and drew upon a global workforce of hunters, merchants and milliners. It was also, however, a highly controversial industry that attracted searing criticism from conservationists and humanitarians. The chapter traces the rise and fall of the trade in feathers and explores the ethical and ecological implications of this arresting but destructive fashion. It looks, too, at the organisations that emerged to protect endangered birds and the challenges they faced in changing laws and attitudes.

While almost any creature with feathers was a target for the plume hunter, two birds in particular bore the brunt of the demand: the egret (Ardea alba) and the ostrich (Struthio camelus). The former, a type of heron, was slaughtered on a massive scale for its handsome breeding plumage and was all but wiped out in Florida; it became the cause célèbre of the bird protection movement, playing a prominent role in much of its propaganda. The latter, the largest living species of bird, was also initially hunted for its feathers, and it too faced extinction. From the 1860s, however, ostriches began to be domesticated and farmed in Cape Colony, offering what most contemporaries saw as a sustainable and humane source of plumes. This chapter explores the contrasting fates of these two birds and shows, in the case of the egret, how milliners propagated lies to defend a coveted commodity.

The Plumage Trade

In the 1860s, a fashion took hold for adorning women’s hats with the plumage of dead birds. The craze began with British birds, such as robins, wrens, goldfinches and kingfishers, but quickly extended to more exotic species such as hummingbirds. Feathers – and later whole birds – appeared on bonnets, dresses, fans, earrings and even shoes.Footnote 4 In 1875, a lady appeared at a ball wearing a dress ‘trimmed with the plumage of eight hundred canaries’.Footnote 5

The birds desired by milliners came from across the globe. Hummingbirds emanated from the West Indies and America, where they were caught in nets, to prevent damage to their feathers, or ‘killed by sand being blown at them by means of a tube’.Footnote 6 Birds of paradise arrived from New Guinea, shot ‘with blunted arrows’ by indigenous hunters, ‘so that stunned, they fall to the ground’.Footnote 7 Lyre birds arrived from Australia, egrets from across the Americas, especially Florida and later Venezuela, and mirasol birds from the pampas, their feathers fetching ‘at least 2,300 dollars per kilo’.Footnote 8 Colonisation and steam shipping opened up new bird populations to exploitation as the nineteenth century wore on, while better weapons accelerated the pace and volume of the killing. Changes in fashion also had a significant impact on the species of birds that were most desired; in 1908, ‘there was a sudden demand for the metallic breast-patch of [the six-plumed bird of paradise], and great numbers were caught’.Footnote 9

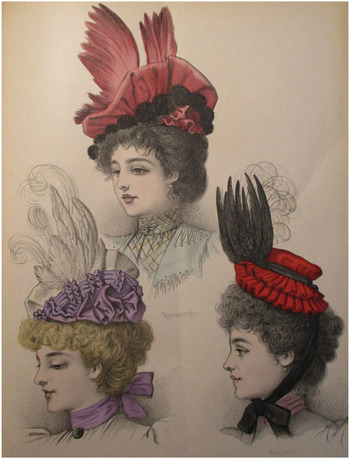

Although they were harvested from around the world, the majority of these birds ended up at dealerships in New York, Paris, and, most prominently, London, where they were sold at quarterly auctions. After passing through the auction houses, feathers were purchased by milliners and dressmakers, who transformed them into stylish adornments for female consumers. Corpses were stuffed, eyes replaced with glass beads, wings pulled off or rearranged and feathers dyed to create more striking colours. The finished articles would then appear in the windows of high-street stores, by turn tempting and shocking the passing public (Figure 1.2). Walking along Bond Street in 1885, one horrified viewer witnessed ‘a spray of five goldfinches, wired so as to be worn cross the bodice of a dress’.Footnote 10

Figure 1.2 A selection of the latest feathered bonnets in the Paris Millinery Trade Review, January 1897, plate 4. The lady on the bottom left is wearing egret feathers.

A journalist from the Pall Mall Gazette visited a dealership in birds’ feathers in 1886 to get a first-hand impression of the trade. On entering the premises, he was met by one of the managers, who guided him through the store and some of the workrooms. Hummingbirds, he was told, were ‘most always much worn’, and were sold for ‘5s to 60s per dozen’. The tangara was a ‘great favourite of ladies’, being ‘the only bird which is naturally red’. The ‘white Java sparrow, which we sell for 4s each, is one of the most expensive birds … White birds are always expensive because they are rare.’ After examining ‘[b]ox after box, chest after chest of birds of all colours’, the journalist was introduced to a second employee, a workman, who described how the birds were mounted. The latter explained that corpses were first ‘put out twelve hours on damp sand, and covered with a damp cloth, in order to soften them’ before being ‘stuffed with cotton wool’ and placed over an internal frame. A wire was then ‘passed through each tail feather, so that the tail may be bent to any shape’ and ‘balls of glass … stuck into the bird’s head’ to serve as eyes. Some plumes were dyed – a job done by female convicts at the dealership’s warehouse in Berlin; others were combined to create composite birds never found in nature. Many of the avian cadavers rotted en route to the dealers and had to be thrown away.Footnote 11

What was the extent of the feather trade, and what impact did it have on bird populations across the world? Surviving trade catalogues and newspaper reports give us some idea of the volume. In 1892, one London auction room sold ‘6,000 birds of paradise, 5,000 Impeyan pheasants, 400,000 hummingbirds, and other birds from North and South America, and 360,000 feathered skins from India’ in a single week.Footnote 12 Six years later, the Society for the Protection of Birds (SPB) published a list of birds and feathers sold at the London Commercial Sales Room in Mincing Lane in one of the quarterly auctions. The list included:

Osprey feathers or aigrettes, 6,800 ounces; peacock feathers, 22,107 bundles; peacock neck feathers, 878 pounds; parrots, 35,497 skins; hummingbirds, 24,956 skins; jays, 16,107 skins; bee-eaters, 2,216 skins; Impeyan pheasants, 1,317 skins; kingfishers, 1,327 skins; trogons, 1,403 skins; argus pheasants, 122 skins; paradise birds, 15 skins; orioles, 32 skins; thrushes, 73 skins; owls, 108; toucans’ breasts, 29; various birds, 7,595.Footnote 13

Naturalist and bird defender W. H. Hudson visited a feather auction in Mincing Lane on 14 December 1895 and observed ‘125,300 specimens’ of parrots, ‘mostly from India’. ‘Spread out in Trafalgar Square they would have covered a large portion of that square with a gay grass-green carpet, flecked with vivid purple, rose and scarlet.’Footnote 14

Horrifying in themselves, these figures conceal the true extent of the slaughter. First, quantities expressed in terms of weight obscure the real number of victims, since some birds produced only a few feathers each, which meant that many had to be killed to supply the requisite amount. ‘To produce a kilo … of small plumes,’ for instance, ‘870 birds [egrets] have to be killed, an appalling fact, when one realises that, besides the mutilated and dying 870 large birds, countless numbers of small birds are left starving in the nests.’Footnote 15 Second, as this quotation indicates, the killing of nesting birds could also result in the premature deaths of their chicks, which perished from lack of food when their parents were slaughtered. Bird species with small ranges, moreover, were especially vulnerable to overhunting and quickly succumbed to the onslaught of the feather trade. Birds of paradise, for example, shaped by years of isolation and sexual selection, were often localised to a particular island chain or mountain range, making them susceptible to rapid extinction. As Margaretta Lemon explained,

The common sense of every thoughtful woman must at once tell her that no comparatively rare tropical species, such as the Bird of Paradise, can long withstand this appalling drain upon it, and that this ruthless destruction, which merely panders to the caprice of a passing fashion, will soon place one of the most beautiful denizens of our earth in the same category as the Great Auk or the Dodo.Footnote 16

The craze for feathered millinery thus precipitated a wholesale massacre of the world’s birds, which perished in their thousands to decorate hats, dresses and bonnets.

The Lady and the Law

While many women were clearly comfortable with wearing the corpses and feathers of dead birds, others found the practice repulsive. To kill a wild animal purely to decorate a bonnet appeared frivolous in the extreme. The sheer volume of the trade, moreover, raised fears of species extinction, both locally and globally. For this reason, the feather trade was one of the first animal-based industries to generate widespread disapproval, and – of all the industries examined in this book – the one that spawned the most organised and sustained opposition. An examination of the campaign against ‘murderous millinery’ thus reveals attitudes, tactics and challenges that would surface again in critiques of fur, ivory and exotic pets.

Individuals had spoken out against the fashion for wearing feathers from its inception, but it was in the 1880s that the first formal bird protection organisations came into existence. In Britain, two women, Eliza Phillips and Margaretta Lemon, founded the SPB in 1889, ‘in the hope of inducing a considerable number of women, of all ranks and ages, to unite in discouraging the enormous destruction of bird-life exacted by milliners and others for purely decorative purposes’.Footnote 17 In the USA, the first Audubon Society (named after the naturalist John James Audubon) came into existence in 1886 to prevent: ‘1) the killing of any wild bird not used for food, 2) the destruction of nests or eggs of any wild bird, and 3) the wearing of feathers as ornaments or trimming for dress’.Footnote 18 Both movements expanded rapidly over the following decade, attracting a growing following: the SPB boasted 22,000 members by 1899, while the Audubon Society, after a brief decline from 1888, was re-founded in 1896 and had branches in thirty-five states by 1904.Footnote 19 Women made up a considerable proportion of the movements’ memberships and, in the SPB in particular, were instrumental in its leadership, heading the majority of regional branches.Footnote 20

In attempting to preserve the avian victims of the plumage trade, campaigners essentially had two options. The first was to secure a change in the law to prevent the collection, export and sale of feathers. The second, more difficult, but ultimately more effective option was to foster a change in consumer attitudes, thus removing the demand side of the equation. Bird protection organisations on both sides of the Atlantic experimented with each of these methods simultaneously, hoping to change public attitudes before it was too late. A closer look at their two-pronged strategy illustrates both the problems they were up against and the campaigning techniques that would become central to present-day animal conservation.

Curbing the Slaughter

When it came to legislation, bird protectors initially lobbied for measures that would end, or at least regulate, the slaughter in the field. These generally consisted of close seasons, during which specified birds could not be shot, and the creation of formal reservations or refuges, where all hunting was prohibited. The British Wild Birds Act of 1872 (amended in 1876 and 1880) established a close season for birds between 1 March and 15 August, giving vulnerable species protection during the breeding season.Footnote 21 Similar measures were enacted in British Guiana (1878), where the Court of Policy prohibited the killing, sale or export ‘at any time of year’ of forty native bird species, and in India, where the Wild Birds’ Protection Act (1887) gave local governors the power to prohibit the hunting of selected birds during the breeding season.Footnote 22 In the USA, individual states passed laws to protect local birds, making it a crime to kill selected species at certain times of the year. Twenty-eight states had enacted some form of bird protection by 1904, and several formal bird refuges had been created across the country.Footnote 23

While anti-hunting legislation represented an important step in bird protection, it did not, on its own, put an end to the plumage trade. For a start, game laws were hard to police and reservations worked only if they were properly guarded. The Audubon Society, recognising this, employed wardens to patrol the newly established refuges, funding their work from supporters’ donations. Policing large areas was both difficult and dangerous, however, and by 1909, following the murder of Guy Bradley and two fellow wardens in Florida, the society was expressing considerable pessimism over the effectiveness of the warden system – at least in the Sunshine State. As one commentator lamented,

This Association has spent thousands of dollars in trying to preserve the birds of Florida without any seeming result, as there are far less plume birds in the state than there were when warden Guy Bradley was appointed. As we have already lost two wardens by violent deaths, it does not seem as though the Association were warranted in appointing any further wardens, especially on the west coast, for the present at least, certainly not until the citizens of Florida awake to the value of birds as an asset to the state and establish a Game Commission in order to see that the bird and game laws are enforced.Footnote 24

Bird protection legislation, therefore, was only effective insofar as it was enforced, and bird refuges needed to be constantly monitored, not merely identified on a map.

Another major problem was, of course, that birds migrated, and even the most diligently policed sanctuary could not protect those residents that left its boundaries. Britain or Massachusetts might have stringently enforced bird laws, but these would not help the birds when they were over-wintering in Alabama or Italy, where no such legislation existed. Nor, moreover, was there anything to stop milliners buying the bodies of foreign birds from unprotected areas of the globe, or, indeed, smuggling illegally hunted plumes from one state into another. According to one Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) report, between 20 December 1907 and 15 February 1908, ‘twenty-three cases of dead bird-skins from India were imported as cowhair or horsehair’, while ‘osprey’ feathers were sent from India to Britain ‘by parcel post, declared as dress material’.Footnote 25 To make real progress, therefore, national and international legislation was essential. As William Dutcher remarked, ‘The only way to stop such an unholy traffic in the lives of these beautiful and innocent creatures is to have enacted international laws, prohibiting the possession and sale of the feathers of all wild birds.’Footnote 26

With this in mind, the second phase of bird protection legislation focused explicitly on the trade in coveted plumes, pushing for measures to curb their export and importation. In the USA, the first major breakthrough on this front came with the Lacey Act of 1900, which prohibited the interstate shipment of birds killed in violation of state laws. This meant that a bird killed illegally in Pennsylvania could not be transported to New York, and that any New York milliner found in possession of such a bird could be fined.Footnote 27 Unfortunately, the Lacey Act did not apply in states that had not enacted bird protection legislation and did not cover foreign birds such as the bird of paradise or the egret. The Audubon Society therefore continued its fight against the feather trade, urging all states to adopt its so-called Model Law and working for tighter federal legislation. An attempt in 1909 to ban the importation of egret feathers to New York ended in failure, following stiff opposition from the millinery lobby, but in 1910 William Dutcher secured a crucial piece of legislation when he persuaded the New York legislature to pass the Audubon or Plumage Act, banning the sale of birds for commercial purposes.Footnote 28 The 1913 Underwood Tariff Act finally sounded the death knell of the plumage trade, explicitly prohibiting ‘the importation of aigrettes, egret plumes or so-called osprey plumes, and the feathers, quills, head, wings, skins or parts of skins of wild birds, either raw or manufactured, and not for scientific or educational purposes’.Footnote 29

In Britain and its colonies, the struggle was more tortuous, and a ban on feather imports took longer to accomplish. India got things off to a positive start in 1902 when its government enacted a law prohibiting the export of ‘the skins of all birds other than domestic birds, except ostrich feathers, and skins and feathers exported bona fide as specimens of Natural History’.Footnote 30 London, however, remained ‘the head of the giant octopus of the “feather trade”’, and despite repeated efforts from the SPB, a ban on the importation of plumage proved elusive.Footnote 31 In 1908, when Lord Avebury introduced into Parliament a bill to prohibit the ‘sale or exchange of the plumage, skin or body of any bird’, the millinery trade mounted a vocal defence and prevented it from becoming law.Footnote 32 In 1914, a second Plumage Bill met a similar fate, derailed, in this instance, by the outbreak of the First World War; in 1921, when a third Plumage Bill was introduced, opponents again threatened to block it, arguing that the fact that the bill had taken over a decade to enact was clear evidence of its flawed conception.Footnote 33 Despite the opposition, this final bill did ultimately become law, bringing to an end a cruel but lucrative trade.

The long struggle to end the trade in bird plumage highlighted the difficulties of protecting wild animals hunted for commercial purposes. First, a major issue for bird protectors was the international dimension of the problem and the excuses and/or defeatism this sometimes induced. Critics of the 1908 Plumage Importation Bill argued that if Britain ceased to import feathers the trade would simply shift to the continent and British ladies would travel to Paris to get their hats rather than buying them in London. A feather ban would thus damage the British economy without saving any birds.Footnote 34 In the USA, meanwhile, William Dutcher complained that American birds, though protected at home, were supplying milliners in other countries. ‘America cannot protect her own birds if the countries of the Old World offer a market for the plumage of American birds, as they are now doing … How can the Americans protect their Hummingbirds if they may be killed in South America and sold in England for use wherever birds are used for millinery ornaments?’Footnote 35 The global nature of both birds and the feather trade thus complicated any protective legislation and gave ammunition to opponents of conservation, who argued that there was no point in sacrificing the economic interests of one state merely to benefit those of a neighbour and rival. Committed bird protectors, however, insisted that there was value in taking a moral lead, even if the economic benefits were not immediate. As The Spectator remarked in 1920, ‘if this argument be accepted as valid, we should have to say that it was useless for Great Britain to put an end to the slave trade while others were still carrying it on!’Footnote 36

A second obstacle to reform was the militancy of the milliners themselves and their refusal to countenance any legislation that might interfere with their business. This meant that whenever a bird protection bill was introduced to national or state legislatures, it faced substantial opposition, often bankrolled by representatives of the industry. In the case of the USA, the Feather Importers Association of New York reportedly paid $4,200 to fight two bills designed to prohibit the sale of aigrette and other wild bird feathers within New York State.Footnote 37 In Britain, meanwhile, milliners battled successive attempts to ban the importation of feathers from overseas, disputing the accuracy of conservationists’ claims. One vocal British milliner, C. F. Downham, denounced the folly of attacking a business that ‘forms an important and increasing industry in this country, much in the same manner as the use of ivory, tortoiseshell, furs, etc.’ and denied ‘that we are as soulless destroyers of wild life as the worst collectors of rubber in the Belgian Congo have been destroyers of human life’. He also suggested that, if certain species were declining (which he considered questionable), it was down to human encroachment on previously unsettled areas and hunting for food and sport, not the plumage trade.Footnote 38 Another opponent of reform, a London feather broker, insisted that ‘there were no signs of extinction of the birds mentioned in [Lord Avebury’s] Bill’ and that ‘in the case of the Birds of Paradise the skins have for a long time been worth from 20s. to 50s. each, and yet, in spite of the tempting price, the supply is larger than ever’. A third questioned why ‘the life of a bird that is a means of income through its beauty [should] be preserved more than any other’.Footnote 39 Milliners were thus willing to refute the claims of conservationists and, where necessary, to falsify or misconstrue science to defend their industry – a practice particularly notable in the case of the egret, as discussed later in this chapter. The effectiveness of their tactics highlights the ways in which a comparatively small but powerful group of lobbyists could delay important environmental legislation and mislead public opinion.

Finally, bird protectors were victims of the simple laws of supply and demand. All manner of laws could be passed, and, if enforced, they could be effective, but as long as demand remained strong the birds were still in danger. Hunting bans, bird refuges and trade prohibitions certainly made milliners’ lives harder, but, as long as women were prepared to pay good money for plume-bedecked hats, someone would always be willing to provide them, even if that meant resorting to poaching and smuggling. To really put an end to the trade, therefore, something had to be done to tackle the demand side of the equation. Could ladies or milliners be persuaded not to use the feathers of dead birds on their hats? Could education supplement legislation?

The Press, the Pulpit and the Schoolmaster

Bird protectors certainly hoped so. Alongside lobbying governments to pass protective legislation into law, conservationists devoted considerable energy to reshaping public opinion, conscious that only a permanent change in fashion would bring about the end of the feather trade. A steady stream of pro-bird propaganda emanated from the SPB and from the various Audubon societies, targeted primarily at female readers. This aimed, by turn, to enlighten, admonish, enlist and advise women, persuading them that a change in their buying choices could have a major impact on the survival of threatened birds.

Bird protection organisations employed a wide range of tactics to connect with a female audience. In Britain, the SPB appealed to the clergy ‘to include the Protection of Birds when preaching on Man’s Duty to Animals on the Fourth Sunday after the Trinity’, delivered lectures on birds, illustrated with lantern slides, and took to the streets in July 1911 in the famous ‘sandwich board protests’, showing the public images of slaughtered egrets.Footnote 40 In the USA, the Audubon Society adopted similar tactics, creating a special lending library for schools and publishing educational leaflets alerting readers to the plight of threatened species.Footnote 41 Both British and American societies relied heavily on the press to spread the gospel of bird protection, using newspapers as key conduits for their message. Writing in 1896, the SPB explicitly thanked ‘The Times and The Standard, and also many other London and Provincial newspapers which have published letters on the subject of bird protection, reported meetings of the Society and published articles in support of its work’.Footnote 42 Five years later, Garrett Newkirk of the Florida Audubon Society reported that ‘I have seen a number of articles written by women in such papers as the New York Tribune and St Louis Globe Democrat, pleading for the birds and remonstrating against the wicked custom of wearing them on hats. Such articles are quoted and talked about in the country, and have a great influence.’Footnote 43 Bird protectors thus mobilised the combined forces of ‘the Press, the Pulpit and the Schoolmaster’ to influence public opinion in their favour.Footnote 44

The content of these articles, sermons and pamphlets fulfilled several key functions. First, it aimed to inform, making readers aware of the nesting, breeding and feeding habits of different species of birds and alerting them to the dangers the birds faced from the plumage trade. William Dutcher’s 1904 pamphlet on ‘The Snowy Heron’ (a species of egret), a particularly influential example, began with a detailed description of the heron, covering its anatomy, habits and geographical range. It then went on to explain why egrets were especially vulnerable during the breeding season, when they ‘gather in colonies’ and ‘lose all sense of fear and wildness’. Shifting from zoology to morality, Dutcher condemned the use of egret feathers by the millinery trade, painting a highly emotive picture of starving egret chicks ‘clamouring piteously for food which their dead parents could never again bring them’. This sobering verbal message was reinforced by two contrasting illustrations – the first showing happy egrets nesting peacefully with their young and the second featuring the plucked carcass of a dead bird.Footnote 45 Campaigners hoped that seeing and reading facts like these would make consumers aware of the problem and change their behaviour; at the very least they could no longer use ignorance as an excuse for their actions.

Beyond merely alerting consumers to the plight of persecuted birds, conservationists often went further, seeking to actively shame them. One especially cutting article on the subject compared feather-wearing women to savages, drawing an unflattering parallel between fashionable British ladies and the daughter of a South American dictator (probably Manuela de Rosas) who allegedly ‘appeared at a ball in a magnificent dress festooned with several hundred human ears’.Footnote 46 Another text, an evocative poem published in The Animal World, expressly blamed women for a whole range of abuses against birds, suggesting that many put fashion above moral qualms:

As for William Dutcher, his ‘Snowy Heron’ leaflet concluded with an impassioned appeal to mothers, urging women to empathise more closely with their non-human counterparts: ‘Oh human mother! Will you again wear for personal adornment a plume that is the emblem of her married life as the golden circlet is of your own, the plume that was taken from her bleeding body because her motherhood was so strong that she was willing to give up life itself rather than abandon her helpless infants?’Footnote 48 According to all of these texts, feather-wearing women were barbarous, hypocritical, un-maternal and unnatural, putting personal vanity above the suffering of avian life.

If one aim of the bird protection literature was to make women feel guilty, another more constructive one was to make them aware of their power as consumers and to enlist them into the ranks of the conservationists. This meant targeting influential individuals and institutions run by and for women and persuading them to take a lead in the anti-plumage crusade. To this end, the Audubon Society concentrated on recruiting women’s clubs, entreating ‘the club women of America’ to use ‘their powerful influence’ to ‘take a strong stand against the use of wild birds’ plumage’, especially egret feathers.Footnote 49 The RSPB took an equally proactive approach, asking female members to ‘refrain from wearing the feathers of any bird not killed for purposes of food, the ostrich excepted’. To make the withdrawal process easier, the organisation publicised the Millinery Depot owned by a Mrs White at ‘8, Lower Seymour Street, Portman Square’, London, where conscience-stricken females could purchase hats manufactured ‘strictly in accordance with the principles of this Society’.Footnote 50 Bird protectors believed that such actions, though small in themselves, could exert an influence on fashion and would serve both to save the birds and to redeem the female sex from accusations of unthinking cruelty. As campaigner Mabel Osgood Wright remarked: ‘Every well-dressed, well-groomed woman who buys several changes of head-gear a year can exert a positive influence upon her milliner, if she is so-minded, and by appearing elegantly charming in bonnets devoid of the forbidden feathers, do more to persuade the milliner to drop them from her stock than by the most logical war of words.’Footnote 51

Finally, if female consumers were not willing to abjure the fashion for the sake of the birds, then another group – female (and male) milliners – could also effect change by refusing to stock or sell hats featuring feathers and corpses. Although they were usually painted as the villains of the piece (and not without cause), milliners often insisted that they were merely bowing to the demands of their customers. If this were the case, they might be open to reform, providing conservationists with an alternative conduit for change. Bird protectors on both sides of the Atlantic grasped this opportunity, forwarding propaganda to willing milliners and making them more aware of the ecological cost of their precious feathers. In 1904, for instance, the Audubon Society sent 500 copies of William Dutcher’s pamphlet on the snowy heron to the Millinery Merchants’ Protective Association for distribution among its members, and a further 1,000 to ‘a prominent wholesale millinery firm in Ohio’.Footnote 52 Four years earlier, the Southport branch of the SPB contacted local milliners directly, ‘asking their cooperation in the preservation of our fast-decreasing foreign birds by refraining from exhibiting egrets, herons and paradise plumes in their models, and by not suggesting their use when not expressly ordered’. While much of this propaganda doubtless fell on deaf ears, there is evidence that a few milliners were open to a change in materials. Three of the milliners of Southport supported the SPB’s appeal, two of them stating explicitly that ‘they considered their customers were entirely to blame, and that personally they would gladly cease the supply’.Footnote 53 Another industry insider, a dressmaker named Mrs Leach, condemned the ‘dreadful’ fashion for ‘tiny bright-plumaged birds’ and advised customers to decorate their costumes instead with ‘the feathers of geese, ducks, fowls, pheasants, partridges, etc., sent for the food of man’, which could be ‘painted with water colours’ to imitate ‘the wing of some tropical bird’.Footnote 54 Conservationists thus targeted both the sellers and the buyers of plumage in the hope that one group would have a redeeming influence on the other.

Ostriches and Egrets

How successful were bird protectionists in their efforts, and what impact did their activities have on the fate of the plumage trade’s favourite species? To explore the consequences of the feather craze in more detail, the following two sections focus on two birds with contrasting experiences: the ostrich and the egret. The ostrich, as we have seen, was officially exempted from both Audubon and SPB pledges of plumage abstinence and was classified as a sustainable and acceptable source of feathers. Was this truly the case? And how, where and by whom were ostrich feathers harvested? The egret, on the other hand, was consistently painted as the most tragic victim of the millinery industry, slaughtered in large numbers in China, Florida and later South America. It was also, however, a critical resource for milliners, who were not prepared to relinquish it without a fight. The final section of the chapter explores the arguments mustered by plume hunters to defend their business and the ways in which science was mobilised by both sides to substantiate or discredit rival claims.

‘The Ostrich Excepted’

For women who wanted to continue wearing feathers but who opposed the wanton slaughter of small birds, ostrich plumes represented a sustainable and humane alternative. Originally worn by men, ostrich feathers began to enter female fashion in the second half of the nineteenth century and constituted a viable substitute for egret plumage and hummingbird wings. Although they were traditionally procured by hunting and killing the ostriches that bore them, ostrich feathers assumed a more benign character in the 1860s when farmers in Cape Colony started to rear the birds on their estates, plucking them alive and sending their feathers to Europe. While the humanity of the plucking process remained a matter for debate, most contemporaries saw it as preferable to indiscriminate slaughter of smaller birds and urged women to wear ostrich feathers in place of avian corpses. There ensued a dramatic growth in the ostrich farming industry as South African breeders sought to maximise their profits and agricultural entrepreneurs attempted to naturalise the species in other countries.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, ostrich feathers had been obtained by hunters in the African interior and dispatched to Marseilles, Livorno, Southampton and other major European ports by merchants in Cairo, Tripoli, the Cape, Morocco and Senegal.Footnote 55 In the 1860s, however, there was a shift from hunting to domestication, as farmers in Cape Colony experimented with raising wild ostriches on their estates. Mr L. von Maltitz, one of the first to attempt the process, purchased seventeen four-month-old ostriches in 1864 and successfully reared them on his farm, where they became ‘so tame that they allow themselves to be handled and their plumage minutely examined’.Footnote 56 Messrs Heugh and Meinjes followed his example in the early 1870s; by 1875, they owned a large flock of the birds.Footnote 57 A third farmer, Mr Arthur Douglas, possessed seventy-one ostriches by 1874.Footnote 58 Though generally regarded as inferior to the plumage of their wild counterparts, the feathers produced by these ostriches were deemed to be of suitable quality for export and promised good financial returns for their owners. Von Maltitz estimated that each of his birds would earn him £12 and 10 shillings per biannual plucking – a profitable return on birds that had cost him 5 shillings each to procure.Footnote 59

Encouraged by these early successes, ostrich farming expanded massively during the 1870s, competing with Cape Colony’s other main industries of sheep farming and diamond mining. Writing in 1881, when the business was at its peak, The Star reported that ‘[f]arm after farm [in Port Elizabeth] is being cleared of sheep to make room for ostriches, now all the rage’, with the result that mutton prices in the region had risen ‘to 6d and 7d per lb, on account of sheep farming being pushed aside by ostriches’.Footnote 60 Four years later, The Times noted that, ‘of the millions of goods annually exported from South Africa, 4 millions, or one half, is merely for the adornment of ladies’, ostrich feathers accounting for 1 million and diamonds for the other 3 million.Footnote 61 A total of 96,582 pounds in weight of ostrich feathers was exported from Cape Colony in 1879, serving a growing demand for the product in Europe and the USA.Footnote 62

For those thinking of investing their time and money in ostriches, the primary requirements were large tracts of land and plentiful food. Mr Douglas from Grahamstown kept 300 birds on an estate of around 1,200 acres, providing each breeding pair with a separate paddock.Footnote 63 An ostrich-farming guide published in 1877 recommended between 1,000 and 5,000 acres for a profitable ostrich farm.Footnote 64 Feeding ostriches was relatively simple, given their rather catholic tastes, although many farmers grew lucerne to sustain the birds during the dry season.Footnote 65 Anthony Trollope, visiting Mr Douglas’s farm in 1877, reported that the ostriches there fed ‘themselves on … grapes and shrubs unless when sick or young’.Footnote 66 An article in the Weekly Standard and Express claimed that the ease of feeding a ‘full-grown ostrich … may be inferred from the fact that it will eat seeds, boots, insects and small reptiles as well as sand, pebbles, bones and pieces of old iron … There is even a case on record of a colonist who was accustomed every evening to give his ostrich the newspaper for supper!’Footnote 67

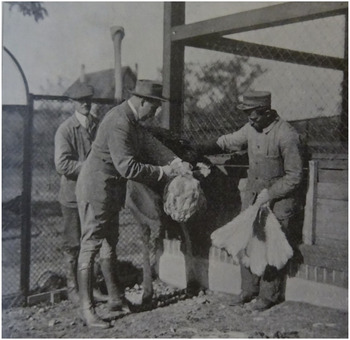

Plucking ostriches was more challenging, as the birds, if frightened, were capable of delivering a debilitating kick with their powerful legs. To counteract this problem, ostrich farmers generally herded their birds into corrals in order to more easily control them, forcing them close together to immobilise their limbs. Trollope recorded that ‘the birds are enticed into a pen by a liberal display of mealies, as maize is called in South Africa’; ‘when the pen is full, a moveable side, fixed on wheels, is run in, so that the birds are compressed together beyond the power of violent struggling’.Footnote 68 A later account described how ‘a stocking’ was ‘slipped over’ the birds’ heads when they entered the enclosure to quieten them, and the quills ‘cut very carefully with special clippers’.Footnote 69 Plucking usually occurred every six to eight months, giving the feathers time to re-grow, and involved either pulling the feathers out manually or cutting them with scissors (Figure 1.3). Whether or not the procedure was painful was a matter for debate, as we shall see, but the general consensus was that ostrich feathers represented a significant humanitarian and environmental improvement on the plumage of dead songbirds.

Figure 1.3 ‘Removing the Plumes’, from Harold J. Hepstone, ‘Modern Ostrich Farming’, The Animal World, November 1912, p. 207.

While South Africa took the lead in the ostrich farming business, other states also showed an interest in the industry, making the ostrich a target not only for domestication, but for naturalisation in other locales. In Egypt, an ostrich farm at Heliopolis, outside Cairo, boasted twenty-five birds by 1881, fed on ‘carrots, turnips, clover, etc., prepared in a specially made “ostrich food mincing machine”’.Footnote 70 In the same year, the French consul in Tripoli sent fifty-two ostriches to Algeria for farming in his nation’s North African colony, while in 1904 five pairs of ostriches were sent from South Africa to Madagascar, resulting in seventy-six birds by 1907.Footnote 71 Beyond Africa, Australia also got in on the ostrich boom, with attempts to acclimatise ostriches in both Victoria and New South Wales. One hundred ostriches lived on a farm at Murray Downs Station by 1882, giving rise to a special factory in Melbourne to wash, trim and dye the feathers they produced.Footnote 72 Twenty years later, twenty-two ostriches were successfully reared ‘in a Sydney suburb’ by an ‘enterprising Australian’; one of the birds, nicknamed ‘the Duke’, sported feathers ‘27 inches in length, 15 inches in width and of the purest white’.Footnote 73

A particularly successful acclimatisation operation took place in the US state of California, where climatic conditions proved favourable to the rearing of this African bird. In 1886, a Californian farmer chartered a ship to convey sixty ostriches from Durban, South Africa, to Galveston, keeping the birds in padded boxes to prevent injury during the seventy-day voyage. After a rest of several days in the Texan port, the fifty-two surviving ostriches were transported to Los Angeles by train, ‘in specially prepared cars’, arriving in good health on their new owner’s farm. The Californian rancher could not offer his animals the same amount of space as his South African counterparts, but he found that they did well on the half-acre plots with which he supplied them. For food, he relied primarily on alfalfa, corn, barley, sugar beet and the occasional orange.Footnote 74 By 1895, there were two ostrich-rearing establishments in California – at Coronado Beach and Norwalk – each boasting sixty-five ostriches.Footnote 75 Ten years later there were also ostrich farms in Arizona, Florida and North Carolina, with an estimated ‘three thousand Ostriches’ in the USA as a whole.Footnote 76 The profitability of the US ostrich industry was assisted by the US Government, which imposed a 25 per cent import duty on foreign-produced ostrich feathers to protect the nascent industry from competition.Footnote 77 In retaliation, South Africa imposed a duty of £100 on every ostrich exported, attempting to retain a monopoly on this prized commodity.Footnote 78

Despite the less favourable climatic conditions, there were also plans to farm ostriches in Europe. In Paris, ostriches featured prominently in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, and a prize was offered in 1857 for their successful introduction.Footnote 79 In Britain, an ostrich-farming syndicate was formed in 1912 in Sussex, purchasing a piece of land for the establishment of an ostrich farm and publishing an article in the Penny Illustrated News to raise the profile of the business. The syndicate’s members claimed that ostrich farming was more profitable and ‘far less laborious than ordinary farming’. They predicted that, ‘in a few years’, ostriches would ‘become as common a feature on the British landscape as sheep and cows’.Footnote 80

While neither the French nor the British operations moved beyond the level of exotic curiosity, an ostrich farm of significant size was established by the German animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck at his menagerie in Stellingen, Hamburg. A strong proponent of animal acclimatisation (he also promoted the domestication of the African elephant), Hagenbeck discovered that ostriches did not need a hot climate in order to survive and experimented with rearing some of his birds in an outdoor enclosure, ‘with no other shelter than that afforded by an unheated open shed’.Footnote 81 Initially a small-scale breeder, Hagenbeck expanded his operation over the years, stocking his farm with ‘over 100 individuals belonging to the five finest varieties of African ostrich in existence’.Footnote 82 He also espoused more ambitious acclimatisation plans, recommending the naturalisation of ostriches in South America, where they could roam ‘the immense prairies’ alongside existing cattle herds. While some feared that this proliferation of ostrich farms might decrease the value of ostrich feathers, Hagenbeck thought otherwise, confident that the market could sustain it. ‘I have little doubt that before long laws will be passed in civilised countries for prohibiting the importation of ornamental birds for ladies’ hats’, and ‘an immediate result of such legislation would be that the demand for and consequently the value of ostrich feathers would rapidly increase; so that there is little danger that this commodity will ever become a drug on the market’.Footnote 83

As Hagenbeck’s comment illustrates, the rise of the ostrich industry in South Africa and beyond was directly connected to the environmental and humanitarian concerns associated with the plumage trade and the changing fashions of European women. Like other animal commodities, moreover, it was facilitated by specific innovations and forms of expertise, as farmers, acclimatisers and manufacturers grappled with the challenges of a new and evolving industry. What were the market forces that stimulated the boom in ostrich farming and what further knowledge exchanges allowed the industry to flourish?

First, the shift from hunting ostriches to farming them was made possible by significant technological advances, the most important of which was the invention of a bespoke ostrich egg incubator. Credited to a South African pioneer, Mr Douglas, the incubator enabled multiple eggs to be hatched at once and relieved the parent birds of the duty of sitting on them while they developed, reducing damage to their feathers and fooling the females into laying additional eggs. Trollope, who visited Douglas’s farm in 1877, described one of these early incubators in detail, emphasising the care and expertise required to operate it:

The incubator is a low, ugly piece of deal furniture, standing on four legs, perhaps eight or nine feet long. At each end are two drawers, in which the eggs are laid, with a certain apparatus of flannel, and these drawers, by means of screws beneath them, are raised or lowered to the extent of two or three inches. The drawer is lowered when it is pulled out, and is capable of hatching a fixed number of eggs. I saw, I think, fifteen in one. Over the drawers, and along the top of the whole machine, there is a tank filled with hot water, and the drawer when closed is closed up so as to bring the side of the egg in contact with the bottom of the tank. Hence comes the necessary warmth. Below the machine, and in the centre of it, a lamp, or lamps, are placed, which maintain the heat that is required. The eggs lie in the drawer for six weeks, and then the bird is brought out – not without some midwifery assistance. All this requires infinite care, and so close an observation of nature that it is not every possessor of an incubator who is able to bring out young ostriches.Footnote 84

As time went by, the incubation process became more sophisticated, increasing in scale and efficiency. In 1908, an ostrich farm in Pasadena, California, was equipped with a large incubator house and a neighbouring ‘brooder’, where newly hatched chicks were fattened up on a diet of ‘alfalfa, dry bone and fine ground grit’ before being released into the open paddocks.Footnote 85 In 1912, Hagenbeck’s ostrich farm comprised ‘stables, [a] pond … feeding troughs, 10 breeding pens … and a hospital for sick and injured birds’, as well as ‘a chick-house’, ‘a show room and [a] factory for feathers’.Footnote 86 Ostrich rearing was thus becoming an industrial activity, assisted by the latest machinery.

Another important element to ostrich rearing – and specifically the naturalisation of ostriches in Europe – was the role played by zoos and menageries. Ostriches appeared regularly in zoos from the mid-nineteenth century and even featured in several international exhibitions. This generated interest in the birds and moved some to recommend their naturalisation as livestock. When twenty-three living ostriches were exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1895, as part of a Somali village, enthusiast G. H. Lane rhapsodised over the birds’ hardiness, observing that they had been ‘exposed in the daytime to all variations of weather and housed at night in a shed’.Footnote 87 A journalist from the Pall Mall Gazette, meanwhile, took the opportunity to quiz the keeper, Mr Peace, on the practicalities of caring for the animals, receiving assurances that they ‘came through the frost last winter on a diet of cabbages’ and had even ‘survived the Canadian winter’.Footnote 88 Captive ostriches thus tickled the entrepreneurial imagination and offered an insight into the nuances of ostrich behaviour. An Animal Care Book compiled by keepers at Manchester’s Belle Vue Zoo noted that the ostriches in their care would ‘eat a heaped bucket of lawn-mown grass’, could ‘peck [themselves] within 12 inches of the base of the neck’, and, in one case, ‘refuse[d] to eat when watched’ – all useful information for anyone thinking of rearing ostriches for profit.Footnote 89

If keepers dispensed valuable knowledge about the handling of ostriches, the sale and marketing of ostrich feathers depended on the expertise and connections of mostly Jewish entrepreneurs. As Sarah Abreyava Stein has demonstrated, Jews were central players in the ostrich feather trade and were visible in all of its main arenas. Jewish merchants purchased feathers from Boer farmers in South Africa. Jewish immigrant workers (mostly women) trimmed, willowed and curled ostrich feathers at workshops in London and New York.Footnote 90 Jewish brokers such as the London-based Salaman family bought feathers at auction for sale to manufacturers, while Jewish financiers bankrolled ostrich farming experiments in the USA. Jewish merchants in Livorno had also played a crucial part in the Mediterranean feather trade, choreographing the movement of feathers across the Sahara by camel train. Stein argues that Jews operated as crucial conduits between farmers and milliners, capitalising on pre-existing skills and transnational contacts. Without this global Jewish diaspora, the ostrich feather trade could not have functioned effectively and would not have assumed the form it did.Footnote 91

What about the supposed ecological and humanitarian benefits of wearing ostrich plumes? Was ostrich farming a benign enterprise, or was it, too, tainted by cruelty? Did the shift from hunting to farming mark an important moment in ostrich preservation?

The question of cruelty centred on whether or not live plucking inflicted suffering. For some commentators the answer was clear: it did not, and ostrich feathers provided a pain-free alternative to the plumage of wild birds, which could be obtained only by killing them. One proponent of this view, vegetarian and prominent anti-vivisectionist Anna Kingsford, explicitly recommended the use of ostrich feathers instead of fur for shawls and wraps, for ‘while sealskins and other furs are obtained with great cruelty, and while small-bird plumage is only procured at the cost of their lives, ostrich feathers … are shorn painlessly from the bird twice a year – much as the fleece is taken from the sheep’.Footnote 92 Another campaigner, Mrs Sturge of the Bristol Branch of the SPB, insisted that self-interest ensured a level of humanity among ostrich owners, since violent and premature plucking would damage their future profits.

There has been a good deal said lately as to how the ostrich feathers are obtained. Though in the old days needless cruelty may have been practised, there is now no excuse for obtaining them in a cruel manner. The birds are now kept on large farms and have to be well cared for, as they are delicate birds. A short time before the feathers are quite matured the birds are driven into cages one at a time and the best feathers cut off with a sharp instrument just about an inch from the skin. The bird is then let loose again. A few weeks later they are again caged and the stumps, if not already out, gently withdrawn, for if blood is drawn feathers will not grow again.Footnote 93

While this benign view of ostrich farming predominated, other commentators expressed greater scepticism as to the humanity of the feather-plucking process, suggesting that there was at least the potential for cruelty. Writing to the RSPCA’s The Animal World in 1891, a member of the society’s Essex branch asked whether ostrich feathers were procured with cruelty, fearing that this must be the case. ‘I have always had the idea that there was considerable cruelty exercised in obtaining ostrich feather plumes – in fact, I have heard they are plucked from the bird when alive. Is that so?’Footnote 94 The magazine’s editor responded to this, and to subsequent queries, in reassuring tones, asserting that ‘[o]striches are seldom ill-treated on farms, where their feathers are cut off, not plucked’.Footnote 95 An earlier piece in The Animal World, however, had been less sanguine, suggesting that the profit-driven nature of the business would inevitably lead to some level of violence. ‘If ripe feathers only can be “plucked” without cruelty,’ the author speculated, ‘is it not likely that mistakes are often made by the pluckers, or that occasional carelessness or recklessness occurs, or that the greed or need of owners induces to early plucking – as in this country it leads to too early shearing of sheep?’ Some ostrich farmers seemed to give weight to these fears when they admitted to using ‘a salve on the skins of the birds, kept for the purpose of healing the wounds’ caused by plucking, suggesting that the procedure was not painless. One French merchant stated that his ostriches, ‘after being completely plucked, have their skins rubbed over with olive oil to alleviate the irritation which naturally ensues from the operation’.Footnote 96 A later account of ostrich farming in Somaliland reported that ‘[e]very six months the ostriches are plucked, and a debilitated bird’s strength sustained after the painful operation by feeding it with chopped mutton and fat, and rubbing ghee or clarified butter as a emollient over the lacerated follicles’.Footnote 97 Ostrich feathers were not, therefore, entirely cruelty-free, and Kingsford’s analogy with sheep shearing may have been overplayed (or, as the Animal World article implied, it was only accurate insofar as both species were abused). An article in The Cornishman claimed that extracting a feather was about as painful as pulling out a human tooth, accusing ‘ladies who wear ostrich feathers’ of ‘encouraging the most cruel and barbarous torture which man can inflict upon a bird’.Footnote 98

If ostrich farming was a mixed blessing from a humanitarian perspective, its impact as a conservation measure seemed less contentious, at least for contemporaries. Before they were domesticated, ostriches appeared to be on the road to extinction. Writing in 1876, the Pall Mall Gazette claimed that ‘it is inevitable that they must die out with the progress of civilisation’.Footnote 99 A decade later, the North-Eastern Daily Gazette expressed a similar view, noting that the earlier practice of hunting ostriches for their feathers was on the point of ‘exterminating them’ when ‘by accident it was discovered that ostriches, notwithstanding their extreme shyness, could be domesticated and would breed in captivity’.Footnote 100 In both cases, the domestication of the ostrich was presented as the bird’s salvation, and the subsequent success of ostrich farming in South Africa was seen as a major conservation success. Speaking in 1920, at a meeting of the African Society, Sir Harry Johnston claimed: ‘If it had not been for the ostrich feather industry in South Africa, the ostrich would now be as extinct as the dodo.’Footnote 101 In that sense, the successful farming of the ostrich was seen as a uniformly good thing from a conservation perspective and represented a much more successful version of the parallel efforts to domesticate the African elephant (see Chapter 3). Again, though, as in the case of the elephant, the choice was very much a stark one between utility and extinction – there was no room for the wild ostrich in this scenario.

The Biography of a Lie

If the plumage trade ultimately proved a mixed blessing for the ostrich, it was an unmitigated disaster for our second species, the egret. Among the birds most heavily exploited by the millinery trade, egrets (sometimes referred to inaccurately as ospreys) were coveted for their handsome white feathers, which were shipped to fashion retailers in huge volumes. In 1905, in London alone, ‘the feathers of 15,000 herons and egrets were sold at auction’; in Paris, the following year, the figure was 230,000.Footnote 102 Egret populations could not sustain these heavy losses and the species soon became the cause célèbre for bird defenders, who fought hard to save it from extinction. Their efforts elicited a storm of protest from milliners, who denied claims of cruelty and attempted to paint the plumage trade in a better light.

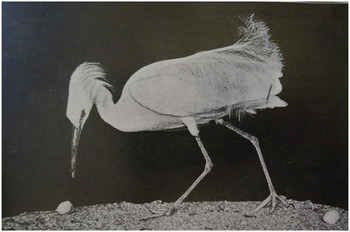

Egret feathers were particularly controversial on account of the manner in which they were obtained. The plumes desired by milliners came from the back of the bird and grew only during the mating season, when the egrets were nesting (Figure 1.4). This meant that not only were the adult birds slaughtered in large numbers to obtain a small volume of feathers, but that their young chicks would starve to death following the killing of their parents. An article in The Star (1894) recounted how ‘when the killing is finished and a few handfuls of coveted feathers have been plucked out, the slaughtered birds are left in a white heap to fester in the sun and wind in sight of their orphaned young, that cry for food and are not fed’.Footnote 103 A US pamphlet on ‘The Horrors of the Plume Trade’ was even more emotive, featuring photographs of egret carcasses and famished chicks; the caption for one of the images read: ‘Fatherless and motherless – no-one to feed them – growing weaker – one already dead from starvation and exposure.’Footnote 104

Figure 1.4 ‘An Egret’, from H. Vicars Webb, ‘The Egret Plume Trade and What It Has Accomplished’, The Animal World, June 1910, p. 103. The delicate feathers on the bird’s back were those most desired by milliners.

While cruelty towards wildlife was, sadly, far from unusual, the melancholy fate of the egret struck a particular chord with people at the time and became a key battleground in the fight against ‘murderous millinery’. Conservationists on both sides of the Atlantic seized upon the egret’s demise as an example of the heartlessness of women and the insatiable greed of the millinery trade. In response, milliners issued a series of claims designed to justify their actions and to ensure the survival of their industry. These ranged from outright denials of any kind of abuse to assertions that past abuses had now ceased, enabling women to purchase egret feathers with a clear conscience. Although these claims were ultimately exposed as untrue, their existence was highly damaging to egret conservation, sending out deceptive messages to consumers that bird defenders mobilised to rebut. A close examination of the ensuing debates reveals both the lengths to which milliners were prepared to go in order to protect a lucrative line of business and the growth in consumer demand for ethically sourced products. It also illustrates the role of science and expertise in discrediting the comforting fictions disseminated by defenders of the feather trade.

In the face of harrowing stories about mutilated adults and starving chicks, the millinery trade’s first response was denial. This is most apparent in explanations for the decline of egrets in the US state of Florida, where the birds had virtually disappeared by the early twentieth century. In one controversial paper read at a meeting of the London Chamber of Commerce in November 1910, milliner Charles F. Downham argued that egret numbers in Florida had indeed diminished in recent decades, but that this was due to ‘American commercial development’ – by which he meant increased human settlement in the area – and definitely not the result of the plume trade, which had never been ‘of importance’ in that state.Footnote 105 Earlier, summoned before a House of Lords Committee, Downham had given a different spin to this argument, asserting that the egrets of Florida ‘were not exterminated; they migrated’. As he elaborated, ‘You might just as well say that because you do not see foxes on Hampstead Heath, foxes are exterminated.’Footnote 106 Other milliners supported Downham’s view that the plume trade was not responsible for the decrease in the egret population of Florida, although the positions they adopted were not entirely consistent. Speaking before the House of Lords Committee, one witness, Mr Weiler, conceded that some egrets may just possibly have been killed in Florida for their plumes but that ‘the tale about the birds being shot at breeding time is a fairy myth’. Another milliner, Mr G. K. Dunstall, declined to say whether or when egrets were shot but attributed the extermination of the birds in Florida to the fact that ‘there never were many Egrets’ in the region, making them vulnerable to both natural and human hazards. As he helpfully explained, with an analogy from closer to home, ‘You can soon exterminate a small number of birds in any small part of the country. If there were Egrets in the Isle of Wight they would soon be exterminated.’Footnote 107

All of these arguments had the potential to undermine the RSPB’s claims of cruelty, so bird defenders in both Europe and America moved quickly to dismiss them. Addressing one claim made by Downham – that the continued supply of egrets proved the sustainability of the industry – the president of the Pennsylvania Audubon Society, Witmer Stone, issued a vehement denial, insisting that: ‘The only reason that the supply continues undiminished is that there are still wild coasts in less frequented parts of the world where the birds can still be procured.’Footnote 108 Responding to the specific issue of whether or not egrets were killed in Florida for their feathers, an RSPB publication, Feathers and Facts (1911), cited the testimony of numerous ornithologists, offering example after example of unregulated slaughter. A report by ‘the late Mr W. E. D. Scott, member of the American Ornithologists’ Union’, described finding ‘a huge pile of half-decayed birds lying on the ground’, their skin and plumes torn off. A similar report from Gilbert Pearson recounted how, while visiting Horse Hummock in central Florida, he had seen ‘heaps of dead Herons festering in the sun, with the back of each bird raw and bleeding’, and ‘young herons left in the nests to perish from exposure and starvation’.Footnote 109 Such evidence discredited the notion that egrets had declined naturally or migrated and instead corroborated William Dutcher’s claim that the egret had been ‘exterminated in the United States by the plume hunters as thoroughly as was the bison by the hide-hunters’.Footnote 110

With the evidence of cruel methods of slaughter mounting, the millinery trade adopted a new tactic. Under pressure from critics, milliners conceded that egret feathers might perhaps be obtained with some degree of cruelty in certain places, including possibly Florida (although no one ever quite admitted this). Consumers did not need to worry, however, because: (1) artificial substitutes were now available and (2) these same feathers could now be acquired cruelty-free from other parts of the world. This led to the advent of two new fictions: the ‘artificial osprey’ and the ‘moulted plume’.

The first of these phenomena, the so-called artificial osprey, made its debut in the mid-1890s and was designed to assuage the consciences of female consumers, who might feel bad about the idea of killing a beautiful bird in the name of fashion. Made, supposedly, from ‘quills, ivorine, silk, wood’ and ‘the feathers of poultry, etc.’, these ‘fake’ feathers looked identical to the real ones and appeared to answer the call of conservationists for a stylish alternative to the plumage of rare birds. With artificial feathers now available, caring women could buy aigrette-adorned hats without fear or guilt, confident that their purchases were not pushing an exotic species to the brink of extinction. Moreover, the artificial feathers were less expensive than the genuine ones; as several milliners argued, ‘they could not be sold so cheaply if they were real feathers’.Footnote 111

Bird protection organisations, however, were suspicious about these ‘artificial ospreys’ and quickly proved them to be fraudulent. One expert, Sir Edwin Ray Lankester, stated in a 1903 interview with the Daily News that ‘[a]n osprey has never been imitated, and whatever the shop keeper may say, it is always the parent bird, slain at the breeding season, which supplies women’s hats and bonnets’.Footnote 112 Another scientist, Sir William Henry Flower of the Natural History Museum, examined several feathers sold as ‘artificial’ in the 1890s and reported that ‘[i]t did not require very close scrutiny to see that they were unquestionably genuine’. The sole exceptions were a few plumes ‘made from the flight feathers of the rhea, or South American ostrich’. Here, however, ‘the remedy was almost worse than the disease, for the rhea is a bird of the utmost scientific interest and importance, and its extinction in a wild state seems to be rapidly approaching’.Footnote 113 Milliners were thus either passing off real feathers as fakes or substituting the feathers of another endangered bird for those of the egret. Both practices were highly dangerous from a conservation perspective, with the promise of cruelty-free plumes muddying the ethical waters and tempting buyers who would not have purchased feathers they believed to be genuine.

The second – and more potent – myth circulated with regard to egret feathers focused not on the authenticity of the plumes but on the manner in which they were obtained. In a new twist to the ‘artificial osprey’ story, milliners now admitted that egret feathers did indeed belong to real birds, but suggested that they were procured without violence. This was possible either because egrets moulted naturally at a certain time of year, or – in other versions of the tale – because they plucked out their own feathers in order to line their nests in the breeding season. Rather than killing egrets, therefore, plumage hunters simply picked up their shed feathers from the ground and delivered them to local dealers. Indeed, so advanced was the egret industry in some parts of the world that the birds were farmed in so-called ‘garceros’ (heronries) and their discarded plumes collected on a regular basis.

The precise location of these heronries remained somewhat vague and tended to shift over time. The earliest reports of their existence placed them in China, where egret feathers were supposedly ‘picked up on the walls’ and sent to Europe. After the Chinese trade in egret feathers collapsed, however, due to the virtual extermination of the birds, tales started to emerge of parts of India where vast tracts of the country were ‘white with shed feathers, lying in sheets like snow’.Footnote 114 One writer, Mrs Isobel Strong, published an article in the New York Tribune in 1899 in which she relayed Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson’s claim (based on conversations with an Indian missionary) that feathers were ‘picked up from the ground during the breeding season of herons’ in India.Footnote 115 Another commentator, a traveller to Nigeria, described how he had seen ‘moulted plumes’ strewn across the jungle floor, just waiting for some enterprising individual to gather them.Footnote 116

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the Asian and African heronries had receded and South America had become the favoured site for discarded egret plumes. In a letter to The Times in 1900, a Mr K. Thompson claimed that in both Nicaragua and Venezuela egrets were ‘so shy and difficult to approach’ that, instead of shooting them, feather hunters simply went ‘round and pick[ed] up the cast plumes’.Footnote 117 A second writer, Leon Laglaize, was even more expansive. In a somewhat mysterious letter from Buenos Aires, dated 10 July 1908 and addressed to an unknown recipient, Laglaize, who signed himself ‘Fellow of the Entomological Society of Paris’, suggested that Venezuelan egrets plucked out their own feathers in order to line their nests, making them easy to gather after the nestlings had fledged. Laglaize described how, in Apure State in Venezuela, large landowners prohibited the shooting of egrets on their estates but instead hired the local Indians to paddle around the swamps in canoes, collecting moulted plumes. ‘After the breeding season, when the young ones leave their nests, the abandoned nests are searched and a valuable amount of feathers is collected,’ asserted Laglaize. ‘The feathers have been skilfully rolled in to furnish and soften the interior of the nest, having been pulled off by the bird itself before laying the eggs.’Footnote 118 It was a similar story ‘[i]n some parts of Brazil and mostly in the provinces of Matto Grosso [sic] and Goyaz [Goiás]’, where ‘the great landowners on the banks of the Rio Alto, Paraguay, and Rio Tacuarí hire the right of picking up the feathers on their estates, under contract that no birds shall be shot’.Footnote 119

Alongside the tales of wild egrets shedding their plumes, rumours also circulated of farms in Africa and the USA where domesticated egrets were shorn humanely of their precious tail feathers. An 1897 article in the New York Times reported the existence of some 400 egrets in a heronry outside Tunis, fed on ‘minced horse and mule meat twice a day’ and relieved of their dorsal plumes twice a year, in May and September.Footnote 120 An 1899 article in the Washington Post likewise detailed the plans of a certain A. Bienkowski to start an egret farm outside Yuma in Arizona, where the birds were to be kept on ‘160 acres of marshy land along the river bottom’, their wings clipped to prevent them from flying away.Footnote 121 Clearly inspired by the success of ostrich farming in South Africa, the idea of domesticating the egret appealed to those seeking a quick profit, and it appeared to offer the possibility of ‘improving’ the species by selectively breeding the birds to propagate those with ‘the most abundant plumes, the most accommodating appetites and the best tempers and constitutions’.Footnote 122 Although it meant loss of liberty and possibly some painful plucking, such a move also seemed like good news for the egret, which, like the ostrich, might now secure its future through domestication. Who could object to treating the exotic egret in the same manner as traditional poultry?

Unfortunately, neither the ‘moulted plumes’ nor the egret farms turned out to have any basis in reality. In the case of the ‘moulted plumes’ scenario, this was deemed biologically untenable, since egrets neither plucked out their own feathers nor used them to line their nests. A few plumes might be shed naturally by the birds, or perhaps pulled out during fights between the males, but these were neither of the quality required nor available in the quantity necessary to furnish the volume of feathers used by the millinery industry. One critic, Albert Pam, a member of the council of the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) with experience travelling in Venezuela, testified before a House of Lords Committee that ‘if you wished to collect feathers you would have to walk several hundred yards for each individual plume you picked up, and in the jungle of the Amazon it would be an extremely difficult occupation’.Footnote 123 Another traveller, Edward McIlhenny, was even more emphatic, informing US conservationist William Temple Hornaday ‘that it is impossible to gather at the nesting places of these birds any quantity of their plumes’.

I have nesting within 50 yards of where I am now sitting dictating this letter not less than 20,000 pairs of the various species of snowy herons nesting within my preserve. During the nesting season, which covers the months of April, May and June, I am through my heronry in a small canoe almost every day, and often twice a day. I have had these herons under my close inspection for the past seventeen years, and I have not in any one season picked up or seen more than half a dozen discarded plumes.Footnote 124

Claims of feather-shedding egrets were therefore either disingenuous or, more likely, false, betraying the ignorance or deceit of their originators.

Reports from reliable individuals on how egret feathers were actually gathered in Venezuela were much more disturbing and did not correlate with Laglaize’s rosy picture. Consulted by the RSPB, one informant, the British ambassador to Venezuela, asserted that egret feathers were not picked up by Indians in canoes but collected by local peons – mostly ranch hands – who shot the birds to fulfil their assigned quotas. There had recently been a move on the part of some landowners in Apure State to protect egrets by outlawing unauthorised shooting on their lands, but this did not extend to public lands, where the birds could be killed without limit. The stories of moulted plumes, moreover, were entirely unfounded, as ‘dead feathers’ (those dropped naturally by living birds) fetched very little on the market due to their inferior quality.Footnote 125 The same was true in Santa Fe, Argentina, where, according to His Majesty’s Consul at Rosario, no egret farms existed and laws to prevent shooting outside the close season were inadequately enforced.Footnote 126

Another witness, an ex-plume collector, offered an even more harrowing account of how egrets were killed. Testifying for the Audubon Society before the New York State Legislature in 1911, A. H. Meyer described the heartless cruelty of Venezuelan feather hunters, who left mutilated birds to die and even used the corpses of half-dead egrets to lure other egrets to a similar fate.

The natives of the country, who do virtually all of the hunting for feathers, are not provident in their nature, and their practices are of a most cruel and brutal nature. I have seen them frequently pull the plumes from wounded birds, leaving the crippled birds to die of starvation, unable to respond to the cries of their young in the nests above, which were calling for food. I have known these people to tie and prop up wounded egrets on the marsh where they would attract the attention of other birds flying by. These decoys they keep in this position until they die of their wounds or from the attacks of insects. I have seen the terrible red ants of that country actually eating out the eyes of these wounded, helpless birds that were tied up by the plume-hunters.Footnote 127

This was a far cry from the idyllic picture of Indians paddling round in canoes gathering cast-off feathers and suggested a much darker reality.

As for the alleged egret farms, these appeared to be, if not complete fictions, then a considerable embellishment of the truth. Individual examples of domesticated egrets may have existed, but the fabled egret farms were never more than grand designs. When Philip Lutley Sclater of the ZSL investigated the supposed Tunis egret farm, he found no trace of it and learned that the enterprise had ended in failure.Footnote 128 Similarly, when ornithologist Herbert Brown enquired into the egret farm at Yuma, he discovered that it consisted of a single ‘little white egret’ kept as a pet at the Southern Pacific Hotel in the town.Footnote 129 South America, the continent most frequently associated with egret domestication and farming, did offer some evidence of tame egrets, but these animals were reared not for their feathers, as milliners suggested, but for the exotic pet trade. US naturalist George K. Cherrie, curator of birds at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, reported that it was ‘not uncommon’ in Venezuela ‘to see two or three Egrets picketed in front of a rancho, a string two or three feet long being tied around one leg and attached to a stake’. These captive birds, however, were transported by river steamer ‘to Bolivar or Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, to be disposed of to tourists’ and were not the source of the mythical ‘moulted plumes’; ‘Egret “farming” is no more an industry than is Parrot “farming”.’Footnote 130 Milliners had therefore extrapolated small realities into large-scale falsehoods. There were no egret farms and no moulted plumes, only thousands of dead egrets shorn of their feathers.

The long battle between milliners and bird protectors over the source of egret feathers highlights the great value attached to this commodity in the first decade of the twentieth century and the tactics deployed by both sides to defend their interests. For milliners, desperate to ensure the survival of their business, it was important to deflect allegations of cruelty and unsustainable hunting. Defenders of the trade in egret feathers therefore argued, initially, that this trade was not to blame for the disappearance of egrets in Florida, which, if it had happened at all, had done so for other reasons. When humanitarian propaganda gave the lie to these claims, however, the milliners changed tack; instead, they tried to pass genuine feathers off as ‘artificial’ ones to reassure concerned customers. When these fake feathers were in turn exposed as genuine, they circulated information suggesting that the means of procuring egret feathers had changed and that the birds were now farmed rather than hunted. None of these claims were true, but the existence of such falsehoods shows that milliners were at least conscious of shifting public opinion and understood the need to present their products in a more ethical light – in itself arguably something of a victory for conservationists.