Antidepressant discontinuation (withdrawal) symptoms were first reported in association with imipramine (Reference Mann and MacPhersonMann & MacPherson, 1959; Reference Andersen and KristiansenAndersen & Kristiansen, 1959), the first tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), shortly after it entered clinical use. These symptoms occur with all classes of antidepressant, including the TCAs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and miscellaneous others such as mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA). A PubMed review conducted when preparing this article identified reports of discontinuation symptoms with 25 antidepressants (Box 1). In recent years the phenomenon has attracted increasing interest, in both the scientific literature and in the lay media (BBC Panorama, 2002, 2003). This article provides an overview of the clinical features of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms, with the emphasis on their recognition, prevention and management. Discontinuation symptoms can occur whenever antidepressants are used, i.e. they are not dependent on the presence of any underlying psychiatric disorder. The pharmacokinetics and dynamics of antidepressants, in particular their half-life, are important determinants of discontinuation symptoms, as are individual patient characteristics, but their discussion is beyond the scope of this article (Reference Schatzberg, Haddad and KaplanSchatzberg et al, 1997; Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998; Reference Bogetto, Bellino and RevelloBogetto et al, 2002).

Box 1 Antidepressants reported to cause discontinuation symptoms

Tricyclic and related compounds

-

• Amineptine

-

• Amitriptyline

-

• Amoxapine

-

• Clomipramine

-

• Desipramine

-

• Doxepin

-

• Imipramine

-

• Nortriptyline

-

• Protriptyline

-

• Trazodone

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

-

• Isocarboxazid

-

• Moclobemide

-

• Phenelzine

-

• Tranylcypromine

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

-

• Citalopram

-

• Escitalopram

-

• Fluoxetine

-

• Fluvoxamine

-

• Paroxetine

-

• Sertraline

Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

-

• Duloxetine

-

• Milnacipran

-

• Venlafaxine

Miscellaneous antidepressants

-

• Mirtazapine (noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant, NaSSA)

-

• Nefazodone

(Based on the authors’ literature review)

The question of addiction

The terms ‘antidepressant discontinuation symptom’ and ‘antidepressant withdrawal symptom’ are used interchangeably in the literature. ‘Discontinuation’ is preferred by some authorities, as it does not imply that antidepressants are addictive or cause a dependence syndrome, whereas the term ‘withdrawal’ may imply this. Both terms are likely to remain in use and it is more important to be clear about what they refer to rather than which is preferable.

The occurrence of withdrawal symptoms does not in itself indicate that a drug causes dependence as defined in ICD–10 (World Health Organization, 1992) and DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). An extensive report published by the Committee on Safety of Medicines concluded that

‘there is no clear evidence that the SSRIs and related antidepressants have a significant dependence liability or show development of a dependence syndrome according to internationally accepted criteria (either DSM–IV or ICD–10)’ (Committee on Safety of Medicines, 2004: p. 3).

This is consistent with earlier publications examining this area (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1999; Reference Haddad and AndersonHaddad & Anderson, 1999; Reference TyrerTyrer, 1999), despite the arguments to the contrary put forward by some critics (Reference MedawarMedawar, 1997).

When considering whether antidepressants are addictive or dependence-forming it is helpful to step back and consider why a label or diagnosis is important to patients. For patients the main advantage of a diagnosis is that it can help predict the treatment and future course of a disorder, i.e. it allows a prognosis to be given. Craving and relapse are common features of dependence on alcohol, opiates and stimulants and both can occur after long periods of abstinence. At a practical level it is the relapsing nature of dependence that makes it so problematic for patients and clinicians. In contrast, managing withdrawal symptoms in those with substance dependence is not the key problem as such symptoms are time-limited. There is no evidence that patients crave antidepressants once they have stopped them or feel compelled to return to taking antidepressants once any discontinuation symptoms, if they occur, have ceased. This difference in prognosis, or long-term course, to that of the syndrome of dependence seen with alcohol, opiates and stimulants seems easily understandable by patients. For a full discussion about whether antidepressants cause dependence see Reference HaddadHaddad (2005), in which it is concluded that antidepressants have no significant liability to cause dependence as defined in ICD–10 and DSM–IV.

Clinical relevance

Antidepressant discontinuation symptoms are important as they can cause morbidity, affect adherence to antidepressant treatment, prevent antidepressants being stopped and can be misdiagnosed, leading to inappropriate treatment. These adverse outcomes are discussed further in this section.

In most patients, discontinuation symptoms are self-limiting, of short duration and mild, but in a minority of cases they can be severe, last several weeks and cause significant morbidity. For example, case reports of SSRI discontinuation reactions have described ataxia leading to falls (Reference EinbinderEinbinder, 1995), fatigue causing difficulty walking (Reference Haddad, Devarajan and DursunHaddad et al, 2001) and electric-shock-like sensations impairing walking and driving (Reference Frost and LalFrost & Lal, 1995). Occasionally discontinuation symptoms lead to urgent consultations and attendance at accident and emergency departments (Reference Pacheco, Malo and AraguesPacheco et al, 1996; Reference Haddad, Devarajan and DursunHaddad et al, 2001).

Poor adherence is common and some patients miss consecutive doses of antidepressants for several days (Reference Demyttenaere, Mesters and BoulangerDemyttenaere et al, 2001). Such breaks may precipitate discontinuation symptoms. Some patients find this beneficial as the symptoms act as a reminder to take medication. However, the experience may cause others to stop their antidepressant permanently, particularly if they worry that the discontinuation symptoms indicate that they are becoming ‘addicts’. Thus discontinuation symptoms can result from, and also cause, poor adherence.

Severe discontinuation symptoms can hinder or even prevent patients stopping antidepressant treatment: symptoms can be so unpleasant that the patient has to restart the antidepressant to stop the symptoms. How often this occurs, and why some patients experience severe problems when most do not, is unknown and warrants further investigation (Reference Schatzberg, Blier and DelgadoSchatzberg et al, 2006). It has been argued that this phenomenon demonstrates that antidepressants are addictive (Reference MedawarMedawar, 1997) but, as discussed above, withdrawal or discontinuation symptoms on their own are insufficient to define dependence in the clinically accepted sense of the word.

An important clinical aspect of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms is the potential for their misdiagnosis, as either a physical or a psychiatric disorder, leading to the offer of inappropriate management for the ‘incorrect’ diagnosis. In particular, discontinuation symptoms may be diagnosed as a relapse or recurrence of the underlying affective illness for which the antidepressant was originally prescribed, although other scenarios exist (Box 2). It is not known how often misdiagnosis occurs. In our experience it usually results from clinicians’ unfamiliarity with antidepressant discontinuation syndromes rather than the symptoms being difficult to diagnose.

Box 2 Examples of the misdiagnosis of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms

1 Misdiagnosis as adverse effect of new medication

Discontinuation symptoms that follow antidepressant switching may be incorrectly diagnosed as side-effects of the new antidepressant (Reference Haddad and QureshiHaddad & Qureshi, 2000), which may be stopped on the assumption that the patient cannot tolerate it. This scenario usually occurs when switching across antidepressant classes; discontinuation symptoms are uncommon when switching between antidepressants with similar mechanisms of action.

2Misdiagnosis as recurrence of the underlying psychiatric illness

Discontinuation symptoms that follow recovery from a depressive illness and termination of antidepressant treatment may be misdiagnosed as a recurrence of depression, i.e. a further depressive episode. This may lead to unnecessary reinstatement of the antidepressant and a more negative prognosis, with significant social implications. The same effect can occur when antidepressants are used to treat other psychiatric disorders, for example discontinuation symptoms may be misdiagnosed as a recurrence of generalised anxiety disorder or panic disorder.

3Misdiagnosis as failure to respond to treatment

Discontinuation symptoms due to covert non-adherence to acute antidepressant treatment may be mistaken as worsening of the underlying illness (depression or other psychiatric disorders) and lead the doctor to incorrectly conclude that treatment is ineffective. As a result the antidepressant dose may be increased, an augmentation strategy adopted or an unnecessary switch made to another antidepressant.

4Misdiagnosis of discontinuation mania and hypomania

Manic and hypomanic symptoms occur as rare antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. If a patient with unipolar depression develops such symptoms, but it is not recognised that they are discontinuation reactions, an erroneous diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder may be made and the patient inappropriately started on long-term treatment with a mood stabiliser.

5Misdiagnosis as physical disorder

Many discontinuation symptoms are physical. Failure to diagnose them may lead to unnecessary referrals and investigations in an attempt to identify a ‘physical’ problem. Examples include a case in which neurological symptoms due to paroxetine discontinuation led to a neurology referral, a computerised tomographic brain scan and electroencephalograph (Reference Haddad, Devarajan and DursunHaddad et al, 2001) and a case in which dizziness due to fluoxetine discontinuation led to an ear, nose and throat referral and magnetic resonance imaging of the head (Reference EinbinderEinbinder, 1995).

Core clinical features

Nature of symptoms

Antidepressant discontinuation symptoms are diverse and differ between antidepressant classes. A review of published case reports of SSRI discontinuation reactions identified over 50 different symptoms (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998). Discontinuation reactions occur on a spectrum in terms of both the number and severity of symptoms, ranging from an isolated symptom to a cluster and from mild to severely disabling. This raises the issue of a diagnostic threshold. However, there is no accepted definition of an antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, although operational criteria have been proposed (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998; Reference Black, Shea and DursunBlack et al, 2000). The occurrence of different symptom clusters, or discontinuation syndromes, adds a further level of complexity. A so-called ‘primary’ (‘general’) discontinuation syndrome is the most common syndrome encountered with the SSRIs and SNRIs. Extrapyramidal syndromes and mania/hypomania can occur as rare discontinuation syndromes with various classes of antidepressant. All these syndromes, and even isolated discontinuation symptoms, appear to share several common features: time of onset of symptoms relative to stopping the antidepressant, duration of symptoms when untreated and response to restarting the antidepressant. These general characteristics are discussed further in this section, and specific syndromes are discussed in the subsequent section.

Time of onset

Discontinuation symptoms usually appear within a few days of stopping an antidepressant or, less commonly, reducing the dose. Onset of symptoms after more than 1 week is unusual. In a naturalistic study of 97 patients the mean time of onset of discontinuation symptoms was 2 days after stopping an SSRI (Reference Bogetto, Bellino and RevelloBogetto et al, 2002). In a series of 160 adverse drug reaction reports of paroxetine discontinuation reactions the median interval between stopping paroxetine and symptom onset was 2.1 days (Reference Price, Waller and WoodPrice et al, 1996). Within this data-set symptoms occurred within 4 days in 86% and within 1 week in 93%.

Duration

Most antidepressant discontinuation reactions are of short duration, resolving spontaneously between 1 day and 3 weeks after onset. Reference Bogetto, Bellino and RevelloBogetto et al(2002) reported that the mean duration of SSRI discontinuation symptoms was 5 days. In 71 untreated paroxetine discontinuation reactions reported by doctors as adverse drug reactions (Reference Price, Waller and WoodPrice et al, 1996), and presumably representing the severer end of the spectrum, the median duration was 8 days (range 1–52 days).

Effect of restarting medication

Clinical experience is that discontinuation symptoms usually resolve fully within 24 h if the original antidepressant is recommenced. Several studies have demonstrated the resolution of symptoms at assessment 1 week after reinstatement of the original antidepressant (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998) or a pharmacologically similar one (Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al, 2007).

Specific syndromes

Primary SSRI discontinuation syndrome

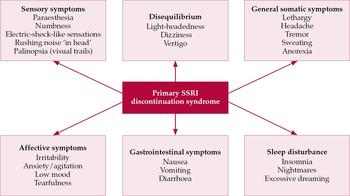

This is the most common discontinuation syndrome seen with the SSRIs. The term ‘primary’ (or ‘general’) is used to differentiate it from rare SSRI discontinuation syndromes such as extra-pyramidal syndromes and mania. The physical and psychological symptoms of primary SSRI discontinuation syndrome can be divided into six groups (Fig. 1). The most common symptoms are dizziness, nausea, lethargy and headache (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998). Some patients experience sensory symptoms (e.g. sensations resembling electric shocks) or symptoms of disequilibrium (e.g. dizziness) in brief bursts when they move their head or eyes. Such symptoms are highly characteristic of primary discontinuation syndrome. The syndrome was initially reported in case reports and adverse drug reaction reports (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998) but its features have been confirmed in several double-blind studies in which SSRI treatment is briefly interrupted with placebo (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998; Reference Michelson, Fava and AmsterdamMichelson et al, 2000; Reference Judge, Parry and QuailJudge et al, 2002). A similar discontinuation syndrome occurs with venlafaxine (Reference Fava, Mulroy and AlpertFava et al, 1997) and duloxetine (Reference Perahia, Kajdasz and DesaiahPerahia et al, 2005).

Fig. 1 Key symptom groups of primary SSRI discontinuation syndrome. Common or characteristic symptoms are listed, but many others are reported. Patients vary in the number and combination of symptoms they manifest.

Primary TCA discontinuation syndrome

This shares four of the six SSRI symptom groups (Fig. 1). The remaining two groups, sensory abnormalities and problems with equilibrium, seem to be less common with TCAs and can be regarded as SSRI specific. It is unclear whether primary SSRI and TCA discontinuation syndromes would be better regarded as several sub-syndromes.

MAOI discontinuation syndrome

Reactions to MAOI discontinuation, particularly those reported with tranylcypromine, tend to be more severe than with other antidepressants. The clinical picture may include: (i) a worsening of depressive symptoms, exceeding the severity of the state that originally led to treatment (Reference Halle and DilsaverHalle & Dilsaver, 1993); (ii) an acute confusional state with disorientation, paranoid delusions and hallucinations (Reference Liskin, Roose and WalshLiskin et al, 1984; Reference RothRoth, 1985; Reference Halle and DilsaverHalle & Dilsaver, 1993); and (iii) anxiety symptoms, including hyperacusis and depersonalisation (Reference TyrerTyrer, 1984).

Rare syndromes

Case reports have described a variety of reactions to discontinuation of antidepressants, including extra-pyramidal syndromes and mania/hypomania. The incidence of these syndromes is unknown, but the fact that they have not been observed in clinical studies suggests that they are uncommon. Sudden onset of mania/hypomania has been reported with termination of TCAs (e.g. Reference Mirin, Schatzberg and CreaseyMirin et al, 1981), SSRIs (e.g. Reference SzabadiSzabadi, 1992; Reference Bloch, Stager and BraunBloch et al, 1995), MAOIs (e.g. Reference RothschildRothschild, 1985), venlafaxine (Reference Goldstein, Frye and DenicoffGoldstein et al, 1999) and mirtazapine (Reference MacCall and CallenderMacCall & Callender, 1999). The phenomenon has been reported in patients with unipolar depression and bipolar disorder. Parkinsonian symptoms have been reported following missed doses of desipramine (Reference Dilsaver, Kronfol and GredenDilsaver et al, 1983a ), dystonia on stopping fluoxetine (Reference Stoukides and StoukidesStoukides & Stoukides, 1991), and akathisia on stopping venlafaxine (Reference WolfeWolfe, 1997), fluvoxamine (Reference HiroseHirose, 2001) and imipramine (Reference Sathananthan and GershonSathananthan & Gershon, 1973). Various other discontinuation symptoms have occasionally been reported, but it is difficult to be sure that the relationship with drug termination is causal rather than a spurious association.

Incidence

Several factors influence the incidence of discontinuation symptoms. Symptoms are more common when higher antidepressant doses are stopped (Committee on Safety of Medicines, 2004; Reference Perahia, Kajdasz and DesaiahPerahia et al, 2005) and when the duration of treatment has been longer (e.g. Reference Kramer, Klein and FinkKramer et al, 1961). However, a plateau in incidence appears to be reached fairly early on in treatment, with duration beyond this resulting in no further increase (Reference Perahia, Kajdasz and DesaiahPerahia et al, 2005; Reference Baldwin, Montgomery and NilBaldwin et al, 2007). For example in a review of duloxetine studies, extended treatment with the drug beyond 8–9 weeks did not appear to be associated with an increased incidence or severity of symptoms (Reference Perahia, Kajdasz and DesaiahPerahia et al, 2005). Intuitively it makes sense that symptoms would be more likely if the antidepressant were stopped abruptly rather than tapered down, although such an effect has not been demonstrated in clinical studies. The methodology by which discontinuation symptoms are defined and assessed will also influence incidence rates.

Discontinuation symptoms are a common occurrence with many antidepressants. Reference Fava, Mulroy and AlpertFava et al(1997) reported that during the 3 days following stoppage of venlafaxine and placebo under double-blind conditions, seven (78%) of nine participants treated with venlafaxine and two (22%) of nine placebo-treated individuals reported the emergence of adverse events, a statistically significant difference. Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al(2007) reported that 13 of 28 patients (46%) fulfilled criteria for a discontinuation syndrome (defined as the onset of three or more new symptoms on a checklist) when assessed 5–7 days after stopping an SSRI or venlafaxine.

Antidepressants differ in their propensity to cause discontinuation symptoms. For example in a 6-week double-blind study that compared milnacipran with paroxetine both drugs were equally effective in treating depression, but after treatment discontinuation, paroxetine was associated with significantly more discontinuation symptoms (Reference Vandel, Sechter and WeillerVandel et al, 2004). Among the SSRIs several prospective studies have show that paroxetine is associated with the highest incidence of discontinuation symptoms and fluoxetine the lowest (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998; Reference Michelson, Fava and AmsterdamMichelson et al, 2000; Reference Bogetto, Bellino and RevelloBogetto et al, 2002; Reference Judge, Parry and QuailJudge et al, 2002; Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al, 2007).

Differential diagnosis

The three key features that suggest the diagnosis of an antidepressant discontinuation syndrome are: (i) the abrupt onset of (ii) characteristic symptoms (iii) within a few days of an antidepressant being stopped or reduced in dose. A discontinuation syndrome that occurs when an antidepressant is stopped following recovery from a depressive illness must be distinguished from a recurrence (i.e. a new episode) of depression. If there are doubts over diagnosis, and symptoms are not severe, then the clinician and patient can monitor the course of the symptoms and reserve a definitive diagnosis to a later date. If adopting this approach the clinician should give a full explanation to the patient. A sudden onset of symptoms with spontaneous resolution within about 10 days is the norm with discontinuation reactions (Reference Price, Waller and WoodPrice et al, 1996; Bogettto et al, 2002). In contrast, one would expect symptoms of a depressive illness to start more gradually, worsen with time and be more persistent; a 2-week duration of symptoms is mandatory for a diagnosis of a major depressive episode in DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Mania

Mania that occurs after a patient with unipolar depression has stopped taking an antidepressant may be a discontinuation reaction or it may be independent of antidepressant stoppage and an indicator of bipolar I disorder. The onset of symptoms within days of antidepressant stoppage would strongly suggest a discontinuation syndrome. As the manic symptoms are identical irrespective of the aetiology, differentiation is not as clear as when differentiating the primary SSRI or TCA discontinuation syndromes from a recurrence of depression. In the latter case characteristic symptoms such as dizziness and paraesthesia, which are uncommon in a depressive illness, can facilitate the diagnosis of a discontinuation syndrome. If the treatment adopted for presumed ‘discontinuation mania’ is antidepressant reinstatement then it is advisable to monitor the patient closely, ideally as an in-patient, because if the diagnosis is incorrect and the patient has a bipolar disorder then the antidepressant may exacerbate the manic symptoms. If there is doubt about the aetiology it seems best to treat the mania symptomatically using an antipsychotic rather than to restart the antidepressant.

Non-adherence

Discontinuation symptoms are not confined to the cessation of an antidepressant on a doctor's advice. Non-adherence to antidepressant treatment is common and often covert unless inquired about. Consequently a discontinuation syndrome should also be considered when unexpected physical or psychological symptoms arise in a patient prescribed an antidepressant. In such cases it is important to ask the patient, in a non-critical manner, whether they are taking the medication as prescribed and, if not, about the relationship between missed doses, the onset and continuation of symptoms. When physical symptoms predominate, clinical judgment will determine when a physical examination and investigations, particularly blood tests, are needed to exclude physical disorders.

Prevention

Tapering after successful treatment

Tapering antidepressants at the end of treatment, rather than abrupt stoppage, is recommended as standard practice by several authorities and treatment guidelines (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, 1999; Reference Anderson, Nutt and DeakinAnderson et al, 2000; British Medical Association & Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2007) and in the summary of product characteristics of many antidepressants. Recommendations on taper length vary. For example the British National Formulary (BNF; British Medical Association & Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2007: p. 200) recommends that antidepressants administered for 8 weeks or more should, wherever possible, be reduced over a 4-week period. Other authorities recommend more cautious tapers. However, there are no controlled data to recommend the effectiveness of tapering, the length of time over which it should occur or the minimum dose that one should taper to before cessation (Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al, 2007).

The only randomised published study to have assessed the effect of duration of tapering on discontinuation symptoms is Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al(2007). This open study recruited patients with major depressive disorder in whom the treating clinician wanted to switch the existing antidepressant, either an SSRI or venlafaxine, owing to lack of response. Participants completed standard scales assessing discontinuation symptoms and depressive symptoms at baseline (on their original antidepressant) and after a 3-day or 14-day taper followed by a washout period (no antidepressant prescribed) of 5–7 days. There was a significant increase in both depressive symptoms (including suicidal ideation) and discontinuation symptoms between baseline and assessment at the end of the drug-free period, with a ‘discontinuation syndrome’ (> 3 new symptoms) occurring in 46% of patients. However, taper duration had no significant effect on the increase in either discontinuation symptoms or depressive symptoms or the incidence of a discontinuation syndrome. Owing to the design of this study it is impossible to know whether abruptly stopping the antidepressant would have led to more discontinuation symptoms than the 3-day taper. The results also imply that if tapering SSRIs and venlafaxine is beneficial in reducing symptoms, and intuitively one would expect it to be, then its duration needs to be in excess of 14 days for most patients.

The only evidence that tapering antidepressants is of benefit comes from several case reports that describe discontinuation symptoms being suppressed by reintroduction of the antidepressant, with a subsequent taper preventing their re-emergence (e.g. Reference Dominguez and GoodnickDominguez & Goodnick, 1995; Reference BenazziBenazzi, 1996). In practice it seems that individuals vary greatly in their propensity to experience discontinuation symptoms and the duration of taper that is required to prevent such symptoms.

When antidepressants are stopped at the end of a successful treatment period, without any intention to switch, then there is no time pressure to limit the duration of the taper. Some of the factors that will influence the duration of taper are listed in Box 3. Routine tapering is probably unnecessary when antidepressants have been prescribed for less than 4 weeks, as discontinuation symptoms are unlikely to occur with such a short duration of treatment. Abruptly stopping an antidepressant is justified if a patient has developed serious side-effects believed to be due to the antidepressant, there is a medical emergency warranting stopping the antidepressant or the antidepressant has induced mania. Further details on the practicalities of tapering antidepressants are provided in the final section of this article, entitled ‘Management’.

Box 3 Factors that may influence the duration of taper

-

• The propensity of the antidepressant to cause discontinuation symptoms

-

• The dose of the antidepressant

-

• Whether the patient has a previous history of discontinuation symptoms

-

• The degree of urgency associated with stopping the antidepressant

Tapering and antidepressant switching

The Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al(2007) data imply that if tapering SSRIs and venlafaxine is beneficial in reducing discontinuation symptoms, then it needs to continue for more than 14 days for most patients. When switching antidepressants because of lack of efficacy, a taper in excess of 14 days before starting the new antidepressant is likely to be impractical as it would cause excessive delay before starting the new drug. An abrupt switch or start–taper switch allow the new antidepressant to be started immediately and are preferable, assuming that there are no potential drug interactions that warrant a drug washout period. A start–taper switch refers to starting the new antidepressant and simultaneously gradually tapering the previous one. Whether an abrupt switch or start–taper switch is chosen partly depends on the likelihood of discontinuation symptoms occurring, which in turn depends on the pharmacological similarity between the two antidepressants.

Several case reports describe antidepressant discontinuation symptoms rapidly resolving, usually within 24 h, after a new but pharmacologically similar antidepressant is commenced (e.g. Reference Keuthen, Cyr and RicciardiKeuthen et al, 1994; Reference Giakas and DavisGiakas & Davis, 1997; Reference BenazziBenazzi, 1999) although this is not always the case (Reference PhillipsPhillips, 1995). This ‘cross-suppression’ means that an abrupt switch can be used when switching between pharmacodynamically similar agents, for example when switching from one SSRI to another SSRI or an SNRI or when switching between SNRIs. If the pharmacology of the two antidepressants is sufficiently different to suggest that the second agent will not suppress symptoms from discontinuation of the first, then a start–taper switch can be used. An abrupt switch may also be considered when switching between pharmacologically different antidepressants, provided that the patient does not have a history of severe discontinuation symptoms and that both patient and clinician are aware that discontinuation symptoms may arise. Most discontinuation symptoms are mild and many of the associated problems arise when they are unexpected, leading patients to worry about their meaning, or increasing the likelihood of doctors making an incorrect diagnosis.

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study used abrupt switching from citalopram (after a mean duration of treatment of 8 weeks) to one of three alternatives: sertraline, venlafaxine and bupropion (Reference Rush, Trivedi and WisniewskiRush et al, 2006). The design makes it difficult to comment specifically on discontinuation symptoms after stopping citalopram but the overall side-effect burden did not differ between the three new drugs, despite the lack of similar pharmacology with bupropion. This suggests that abrupt switching is reasonable in this situation. The prospective study reported by Reference Tint, Haddad and AndersonTint et al(2007) also suggests that discontinuation symptoms are not likely to be a major problem with abrupt switching. In this study, mean scores for discontinuation and depressive symptoms increased significantly following stoppage of either an SSRI or venlafaxine and a 1 week antidepressant-free period. Patients then started a new antidepressant chosen on clinical grounds by the treating clinician. One week after starting the new antidepressant, mean scores on both symptom scales had fallen to near baseline values even though about one-third of the patients had been switched to a noradrenergic antidepressant.

It is important to emphasise that a washout period is essential when switching to and from MAOIs because of the risk of drug interactions that can lead to serotonin syndrome. The BNF (British Medical Association & Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2007) suggests appropriate washout periods, the durations of which differ depending on the details of the MAOI switch. A washout should also be considered when switching from fluoxetine to a TCA, as the long-half life of fluoxetine, plus its ability to inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes, could result in elevation of plasma TCA levels, leading to adverse effects.

Choice of antidepressant

When an antidepressant is selected for a patient the decision should reflect various factors, including the patient's experience of previous antidepressants in terms of efficacy and tolerability, the potential for drug interactions and any cautions or contraindications to prescribing. If a patient has previously experienced a severe discontinuation syndrome or is known to adhere poorly to medication regimens then these factors should also be considered. In such cases an antidepressant with a low propensity to cause discontinuation symptoms (e.g. fluoxetine) may be an appropriate choice.

Education for health professionals

Several surveys in the late 1990s indicated that many health professionals were unfamiliar with the concept of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms (Reference Young and CurrieYoung & Currie, 1997; Reference Donoghue and HaddadDonoghue & Haddad, 1999; Reference Haddad, Tylee and YoungHaddad et al, 1999). For example 30% of UK general practitioners questioned in 1998 (Reference Haddad, Tylee and YoungHaddad et al, 1999) reported being poorly aware of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms and, from other questions, it was apparent that many of the remainder had overrated their knowledge. Increased awareness is necessary if clinicians are to adopt preventive strategies and to effectively diagnose and treat discontinuation symptoms when they arise.

Information for patients

Patients taking antidepressants, or considering antidepressant treatment, need to be provided with information. They need to know that antidepressants should not be stopped abruptly or interrupted as this can cause discontinuation symptoms, and that antidepressants should be tapered at the end of treatment to minimise this risk. It should be explained that although antidepressants can cause discontinuation or withdrawal symptoms they do not cause craving, tolerance and loss of control over medication taking and for this reason antidepressants are not regarded as addictive in the way that alcohol and many illicit drugs are. Providing this information lessens the likelihood of discontinuation symptoms appearing and their misdiagnosis. Although discontinuation symptoms are unlikely to occur when antidepressants have been taken for less than 4 weeks (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998) the intention when starting treatment is to treat for a longer period than this, assuming of course that the drug is effective and well tolerated. Consequently all patients should be warned about discontinuation symptoms before they start taking an antidepressant and also when discontinuation is being contemplated.

Neonatal symptoms

Symptoms in newborn infants following maternal SSRI use in late pregnancy have been described in case reports (e.g. Reference Haddad, Pal and ClarkeHaddad et al, 2005), adverse drug reaction reports (Reference PhelanPhelan, 2004) and in prospective studies (e.g. Reference Laine, Heikkinen and EkbladLaine et al, 2003). Similar symptoms have been reported following maternal use of TCAs in late gestation (e.g. Reference Cowe, Lloyd and DawlingCowe et al, 1982). Symptoms include shivering, tremor, restlessness, increased tonus, respiratory difficulties (ranging from transient tachypnoea to cyanosis), irritability, crying, restless sleep and feeding difficulties. Symptoms are either present at birth or commence within a few hours or days after birth and are usually mild and self-limiting, resolving within 2 weeks. Occasionally symptoms are severe, including seizures and hyperpyrexia, and may warrant admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (Reference Haddad, Pal and ClarkeHaddad et al, 2005). It is unclear to what extent these symptoms represent a neonatal antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, serotonin toxicity (i.e. a direct toxic effect of the antidepressant) or are unrelated to medication (Reference Haddad, Pal and ClarkeHaddad et al, 2005). Different aetiologies may apply in different cases and in some cases a combination of mechanisms may apply. The possibility of discontinuation symptoms arising in breast-fed infants whose mothers suddenly stop antidepressant treatment has been raised (Reference Kent and LaidlawKent & Laidlaw, 1995).

It is recommended that the possibility of neonatal symptoms (as well as other adverse effects of anti-depressants in the newborn) should be discussed with pregnant or breast-feeding mothers who are contemplating starting or continuing antidepressant treatment. The possible risks need to be balanced against the benefits of antidepressant treatment and breast-feeding and the risks of an untreated depressive illness. Decisions should be made on an individual patient basis.

Management

The treatment of discontinuation symptoms depends on (i) whether or not further antidepressant medication is warranted and (ii) the severity of the discontinuation symptoms. If further antidepressant treatment is warranted, irrespective of the occurrence of discontinuation symptoms, then restarting the antidepressant will cause rapid resolution of the symptoms. This scenario usually follows failure to take an antidepressant as prescribed, during either the acute or maintenance phase of an illness. If further antidepressant treatment is not clinically indicated then management depends on the severity of the discontinuation symptoms. Most symptoms are mild and in these cases treatment usually requires only that the patient be reassured about their self-limiting nature. Symptoms can be treated symptomatically if they are of moderate severity. For example insomnia may be treated with a short course of a benzodiazepine. Antimuscarinic agents can help in the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms following TCA discontinuation (Reference Dilsaver, Kronfol and GredenDilsaver et al, 1983a ,Reference Dilsaver, Feinberg and Greden b ), which is consistent with these symptoms being due to cholinergic rebound. If the discontinuation symptoms are severe then the antidepressant can be reinstated, symptoms will usually resolve within 24 h and then the antidepressant can be withdrawn more cautiously. Treatment should always include an appropriate explanation of the symptoms to the patient and follow-up to ensure that the symptoms have resolved.

These principles of treatment apply not only to the primary TCA and SSRI discontinuation syndromes, but also to rare discontinuation syndromes, although the evidence is only from case reports. For example mania/hypomania following antidepressant discontinuation has been reported to resolve spontaneously after a short duration without treatment (Reference Mirin, Schatzberg and CreaseyMirin et al, 1981; Reference Bloch, Stager and BraunBloch et al, 1995) and also to respond to restarting the offending antidepressant (Reference Nelson, Schottenfeld and ConradNelson et al, 1983) or commencing antipsychotic treatment (Reference Mirin, Schatzberg and CreaseyMirin et al, 1981). Extrapyramidal discontinuation symptoms associated with venlafaxine (Reference WolfeWolfe, 1997), fluvoxamine (Reference HiroseHirose, 2001), imipramine (Reference Sathananthan and GershonSathananthan & Gershon, 1973) and desipramine (Reference Dilsaver, Kronfol and GredenDilsaver et al, 1983a ) have been reported to resolve when the responsible antidepressant has been restarted.

If, when attempting to withdraw and stop an antidepressant, severe discontinuation symptoms appear, either during or at the end of a taper, one should consider increasing the antidepressant dose back to the lowest dose that prevented their appearance, and then commencing a slower taper. Some individuals require very gradual tapers to prevent discontinuation symptoms reappearing (Reference Koopowitz and BerkKoopowitz & Berk, 1995; Reference Amsden and GeorgianAmsden & Georgian 1996; Reference Louie, Lannon and KirschLouie et al, 1996). Some antidepressants, including paroxetine, are available in liquid formulations that allow very gradual tapers. When managing SSRI and SNRI discontinuation symptoms another strategy is to switch to fluoxetine, the SSRI with the longest half-life. According to anecdotal reports, fluoxetine can suppress discontinuation symptoms associated with other SSRIs (Reference Keuthen, Cyr and RicciardiKeuthen et al, 1994; Reference BenazziBenazzi, 1999) and venlafaxine (Reference Giakas and DavisGiakas & Davis, 1997). If the switch is successful, fluoxetine can usually be stopped after several weeks of treatment without discontinuation symptoms reappearing. The effectiveness of this strategy appears to reflect the long half-life of fluoxetine (1.9 days) and its active metabolite norfluoxetine, which has a half-life of 7–15 days (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998).

Declaration of interest

P. H. has received reimbursement for lecturing and/or consultancy from the manufacturers of several antidepressants, including GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Lundbeck and Wyeth. He has been a principal investigator in a clinical trial of duloxetine sponsored by Lilly. I. M. A. has received reimbursement for lecturing and/or consultancy from the manufacturers of several antidepressants, including Lilly, Lundbeck and Wyeth.

MCQs

-

1 Discontinuation symptoms are recognised with:

-

a only tricyclic antidepressants

-

b only monoamine oxidase inhibitors

-

c only SSRIs

-

d only SNRIs

-

e all major antidepressant classes.

-

-

2 Characteristic features of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms include:

-

a onset of symptoms about 2 weeks after the antidepressant is stopped

-

b usually severe symptoms

-

c symptom duration of 4 weeks or longer if untreated

-

d resolution of symptoms within 24 h of restarting the antidepressant

-

e symptoms that are more marked in men than in women.

-

-

3 Key principles in preventing and managing anti-depressant discontinuation symptoms include:

-

a warning patients about the addictive nature of antidepressants

-

b tapering antidepressants at the end of treatment

-

c advocating drug holidays to avoid sexual side-effects

-

d restarting antidepressant treatment whenever discontinuation symptoms are suspected

-

e avoiding direct switching from one SSRI to another SSRI.

-

-

4 Characteristic symptoms of SSRI discontinuation reactions are:

-

a auditory hallucinations

-

b emotional numbing

-

c electric-shock-like sensations

-

d obsessional thoughts

-

e disorientation.

-

-

5 SSRI discontinuation symptoms are:

-

a seen only in adults

-

b more common with fluoxetine than with other SSRIs

-

c more common with a shorter, as opposed to a longer, duration of antidepressant treatment

-

d seen only when SSRIs are used in the treatment of depressive disorders

-

e more likely with higher antidepressant doses.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | F | c | F | c | T | c | F |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.