Introduction

Vicarious trauma refers to the impact that working with trauma survivors can have on the individuals working with them (McCann and Pearlman, Reference McCann and Pearlman1990). Vicarious traumatisation is described through Constructivist Self-Development Theory as a cumulative and pervasive process in which the helper’s inner experiences are negatively and permanently transformed through listening to traumatic material frequently and repeatedly over time (Pearlman and Saakvitne, Reference Pearlman and Saakvitne1995). This can include changes in the way individuals view themselves, others and the world (Bride et al., Reference Bride, Radey and Figley2007). Beliefs around trust, safety, intimacy, esteem and control are challenged or disrupted by trauma work (Pearlman and Saakvitne, Reference Pearlman and Saakvitne1995). This may result in increased cynicism, hopelessness and risk awareness in daily life. It shatters people’s view of the world as being safe, predictable and caring through witnessing the cruelty of mankind (Bartoskova, Reference Bartoskova2017; Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992; Sui and Padmanabhanunni, Reference Sui and Padmanabhanunni2016). Herman (Reference Herman1992) proposed that ‘trauma is contagious’ (p. 140).

Individuals may experience emotional and behavioural responses because of repeated exposure to traumatic narratives (Newell and MacNeil, Reference Newell and MacNeil2010). This can include exhaustion/lethargy, anxiety, sadness, anger, guilt, shame and fear as well as a difficulty managing these intense emotional experiences (McCann and Pearlman, Reference McCann and Pearlman1990). As a result, helpers may avoid situations that they perceive as potentially dangerous (Resick and Schnicke, Reference Resick and Schnicke1992). Additionally, McCann and Pearlman (Reference McCann and Pearlman1990) identified the potential for helpers to internalise their client’s traumatic stories which can consequently alter their memory systems. Paivio (Reference Paivio1986) purported that therapists may experience intrusive images, flashbacks or dreams as the part of their memory that stores imagery is altered. Numbing, dissociation and hyper-arousal may also be present (Herman, Reference Herman1992). Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms can be experienced to a lesser degree, it is the cognitive shift that defines vicarious trauma (Elwood et al., Reference Elwood, Mott, Lohr and Galovski2011).

The paralleling of vicarious trauma and PTSD symptoms, along with the idea that ‘trauma is contagious’ (Herman, Reference Herman1992; p. 140), indicates that it is likely that there are adverse clinical implications for the therapeutic relationship. A disruption to the therapeutic alliance, over-stepping boundaries, conflict within professional teams and a pull to rescue or control clients may occur as a defence against overwhelming emotions (Herman, Reference Herman1992). An alternative response may be to avoid, minimise or deny the clients experiences (Baranowsky, Reference Baranowsky and Figley2002).

The cost of caring for individuals who care for trauma survivors is that it is emotionally taxing. This ultimately has an impact on the care individuals provide to service users (Figley, Reference Figley2002; as cited in Figley, Reference Figley2015). The Francis Report (Reference Francis2013) highlighted a lack of compassion and desensitisation amongst staff. These factors contributed to the deaths that occurred due to the inadequate care that was provided. This report highlights the importance of ensuring that the emotional well-being of individuals working in healthcare settings is not overlooked to enhance the quality of care provided to service users.

Recent research has focused on the positive impact of working with trauma survivors and potential satisfaction or growth that emerges during therapeutic work. Some individuals experience positive psychological changes through working with trauma survivors (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Cann2005). Tedeschi and Calhoun (Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004) referred to this as vicarious post-traumatic growth. It is proposed that growth can happen because of vicarious trauma, through infusing new material with existing beliefs (Linley et al., Reference Linley, Joseph and Loumidis2005). It is this enrichment in understanding of self and others which enables individuals to gain skills in relationships, have more appreciation for life and the resilience of mankind, and experience satisfaction from witnessing the growth of others (Herman, Reference Herman1992; Pearlman and Saakvitne, Reference Pearlman and Saakvitne1995; Schauben and Frazier, Reference Schauben and Frazier1995; Shakespeare-Finch et al., Reference Shakespeare-Finch, Smith, Gow, Embelton and Baird2003; Splevins et al., Reference Splevins, Cohen, Joseph, Murray and Bowley2010). Key characteristics include: increased compassion, empathy, sensitivity and tolerance, a drive to live life more meaningfully, a changed sense of priorities, a recognition of new possibilities and a greater sense of personal strength (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Cann2005; Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004). Splevins et al. (Reference Splevins, Cohen, Joseph, Murray and Bowley2010) highlighted an increased sense of admiration, inspiration and hope.

Compassion satisfaction refers to a sense of pleasure that an individual may get from feeling that they have helped their clients in their recovery (Figley, Reference Figley2002). Craig and Sprang (Reference Craig and Sprang2010) described it as a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction emerging because of effective clinical work. It is proposed that the helper’s belief in the efficacy of therapy, and their sense of self-worth is strengthened in this phenomenon (Radey and Figley, Reference Radey and Figley2007).

Policy context

Employee well-being is an important issue particularly following concerns that staff were not being appropriately supported in work (Francis, Reference Francis2013). Sloan et al. (Reference Sloan, Jones, Evans, Chant, Williams and Peel2014) highlighted that less than two-thirds of NHS Trusts had a policy which focused on staff well-being or had implemented recommendations proposed by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (2009) regarding emotional well-being at work. In January 2017, the Prime Minister proposed that an independent review be carried out examining how employers can better support their workforce. The Stevenson/Farmer Review (Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017) outlined six core and four enhanced standards. These predominantly focus on opening-up a dialogue about mental health and raising awareness about the support available.

Review rationale

Exploring whether therapists experience vicarious trauma is important as a therapist’s ability to contain their client’s emotions as well as their own is an important aspect of effective therapy (Pistorius et al., Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008). Having insight into how therapists experience trauma work has important implications for the level of support that services can consider providing, including supervision and training needs. Prioritising therapist well-being ensures that their experiences are validated and processed. Enabling a therapist to make sense of trauma narratives and what this means for their view of the world will maximise the possibility of them remaining in the role and feeing fulfilled and enriched from their work.

There are existing reviews examining the impact of working with trauma survivors on various professions exploring papers using quantitative and qualitative methodology (Baird and Kracen, Reference Baird and Kracen2006; Beck, Reference Beck2011; Cohen and Collens, Reference Cohen and Collens2013; Sabin-Farrell and Turpin, Reference Sabin-Farrell and Turpin2003). This article aimed to review existing qualitative research exploring how therapists experience working with trauma survivors, through meta-ethnographic methodology (Finfgeld, Reference Finfgeld2003). This approach enables re-conceptualisation of themes and has the potential to identify new areas of research (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Pound, Morgan, Daker-White, Britten, Pill and Donovan2011; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Parkes, Wight, Peticrew and Hart2009).

Review aim

The aim of this meta-ethnographic review was to explore and describe how individuals providing therapy to trauma survivors experience their work. Original themes were extracted and re-analysed to integrate existing literature and gain a deeper understanding of therapists’ experience. The objective is to normalise and increase awareness of vicarious trauma for therapists and the organisations supporting them and that by doing so the quality of patient care will be enhanced.

Method

Review type

The articles were reviewed using meta-ethnographic methodology following Noblit and Hare’s (Reference Noblit and Hare1988) guide. Objective idealism underpins this meta-ethnography because it postulates that vicarious trauma exists as a phenomenon outside of human perception. This methodology provides the opportunity to explore the commonalities but also differences across multiple studies that utilise different qualitative methodologies and are underpinned by different theoretical perspectives to explore their shared understanding of vicarious trauma (Barnett-Page and Thomas, Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas2009).

Systematic literature search

The search for literature was carried out using three electronic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Embase to identify articles pertaining to therapists’ experience of working with trauma (see Table S1 in the Supplementary material). The search unveiled a total of 261 articles (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicates, 213 titles were screened for suitability. Of these, 138 articles were identified as either conference/dissertation abstracts or books, and three were not written in English. The abstracts of the remaining 72 articles were subject to inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1), which identified 19 articles as suitable for inclusion. Ten additional papers were identified from the reference section of these 19 papers and were subject to the same inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Flowchart of article selection

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Papers were screened prior to quality appraisal to ensure that at least 75% of the sample were therapists working with trauma survivors, and if they did not meet these criteria they were excluded. Papers that did not provide a breakdown or description of job roles were also excluded. As such a further nine articles were excluded. A total of 20 papers were selected for quality appraisal.

Following quality appraisal using the framework developed by NICE (2012), four papers were excluded as these were considered poor quality. Factors considered to be poor quality included minimal discussion of ethical considerations, limitations and implications of the research and reflections on how the role of the researcher may have affected the results. These factors present a threat to the validity of this review as it is difficult to tease out any bias or follow the process of conducting the study. Similarly, articles that included minimal quotes would have made it very difficult to fully understand the authors’ thought process when interpreting themes. As this review was re-analysing original themes it was considered that these articles would weaken the impact of the synthesised results. Thus, of the 20 papers appraised, only 16 were included in the review (Fig. 1). Each paper has been assigned a number to aid clarity in the results section (Table 2). Three papers were considered good quality and 13 were considered medium quality.

Table 2. Papers included in the review with notes on research methodology used

Data extraction and synthesis

Key characteristics and themes were extracted from each paper and initial ideas around what the data demonstrated were noted. Each paper was reviewed in chronological order and reflected on whether the paper represented similar ideas to the previous paper or a different concept. The original interpretations were reviewed and quotes were extracted to define and provide support for the themes. Reciprocal translation was used as the themes in multiple studies were similar and were thus organised into common themes (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Harden, Newman, Gough, Oliver and Thomas2012).

Due to the nature of meta-ethnographic methodology there is an element of interpretation. To ensure the new themes were clearly grounded in the existing themes and limit bias, the researcher sought input from her supervisor in identifying and naming emergent themes across the multiple studies.

Results

The analysis produced five superordinate themes: ‘altered outlook on life and perception of self and other’, ‘emotional experiences’, ‘physiological experiences’, ‘cognitive experiences’ and ‘behavioural responses’ (Table 3). These themes were derived through combining the similarities and identifying the differences across the papers to provide a synthesised understanding of therapists’ experiences of working with trauma survivors.

Table 3. Outline of superordinate and subordinate themes

Altered outlook on life and perception of self and other

This theme represents the therapists’ changed view of self, others and the world based on their exposure to trauma narratives. Therapists identified negative beliefs that had developed through the horror of listening to traumatic material. There was, however, a sense of growth and development that emerged through engaging with this population.

View of the self

This sub-theme relates to a marked change in therapists’ view of self because of working with trauma survivors. There is a real sense of inadequacy, low self-esteem and doubting of one’s professional abilities (papers 1–3, 8, 10). One therapist described how they felt like ‘[they] didn’t know what [they were] doing’ (Baker, Reference Baker2012; p. 7). Another described ‘feeling completely incompetent’ (Bartoskova, Reference Bartoskova2017; p. 38). The idea that it takes longer to achieve change when working with trauma survivors (2–3) brings with it the implicit notion that therapists are repeatedly exposed to traumatic material. Considering this, it is likely that this contributes to the tainted beliefs therapists have about themselves as an ineffective clinician as they are overloaded with sensitive information, yet progress is slow. Additionally, it is when things are not going well within therapy that therapists internalise this and blame themselves (3), asking themselves ‘what [is] wrong with me?’ (Baker, Reference Baker2012; p. 7) or have beliefs that they are not fit to be a therapist because they experience intense emotions (10).

An experience of growth and development was evident (1, 13, 15–16). Therapists were observed to focus more on their own abilities, strengths, resilience and potential for growth (15–16) because of witnessing their client’s resilience, with a sense of ‘if their clients can do it, so can they’ (1, 15–16). There was also a sense of viewing the self as stronger because of listening to stories of how people have overcome adversity (5, 11). One therapist suggested that the stronger they become, the more able they feel to cope with life’s situations (5). Witnessing post-traumatic growth and progress in clients increased therapists’ confidence and belief in their effectiveness as a clinician (3, 11, 13, 15).

View of others and the world

This sub-theme relates to a shift in the way therapists view the world because of exposure to traumatic stories. Therapists spoke about the impact of having an increased awareness of the capability of mankind for cruelty (the ‘dark side of human nature’;Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Cann2005; p. 253) and the existence of profound suffering. There was a tendency to focus on the violent acts that people perpetrate and at times to overgeneralise the existence of abuse (1, 10, 13, 16). Therapists expressed shock and disgust as their previously held (‘naïve’, Pistorius et al., Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008; p. 188) beliefs were shattered by the realisation that the world is dangerous, unsafe and unfair (3–4, 8, 13–14, 16). These beliefs challenged previously held ideas around safety, trust and control (2, 8). There was a heightened sense of danger (8) and an idea that such beliefs were ‘forever changed and there’s nothing that can alter that’ (Bell, Reference Bell2003; p. 516). One therapist described how it ‘shaded my view of life’ (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Cann2005; p. 254).

To make sense of their experiences, therapists viewed others as either victims or perpetrators, and the world as either safe or unsafe (14). This potentially enabled the therapists to distance themselves from the horror of the ‘darker side of life’ whilst also remaining vigilant to its presence. Engaging with trauma survivors also challenged therapists’ spirituality (1–2, 8, 12).

For some therapists, working with trauma survivors had a positive impact on their view of the world. As opposed to focusing on trauma survivors as victims, there was a real sense of strength and resilience in being able to survive and continue to live their lives through witnessing their clients change and grow (1, 4–6, 8, 15). Some therapists were able to transfer the notion of strength and resilience to their view of others (1, 6, 15). There was a real sense of hope and optimism because of witnessing trauma survivors cope and thrive (1, 3, 5–7, 10, 12, 14–16).

Having an increased awareness of the darker side of life allowed some therapists to develop a broader view of life which changed their view of perpetrators, enabling them to be more empathic to factors that predispose acts of violence (1, 15). Some therapists were more open to broadening their spirituality because of the existential nature of trauma (1–2, 6).

Emotional experiences

This theme represents the emotions experienced by therapists working with trauma survivors which were wide-ranging, intense and often damaging. However, some positive emotions were experienced through being involved in the recovery of trauma survivors.

A range of fluctuating, distressing emotions were experienced by therapists exposed to trauma narratives (14). Listening to the horrendous ordeals that trauma survivors have been through left therapists feeling sad (1–2, 8, 10, 13–14, 16) and angry (1, 6, 16). This is unsurprising given the disruption to previously held beliefs that the world is safe and fair (3–4, 8, 13–14, 16). There was a sense of fear (1–2, 6–7, 13) and anxiety (1–2, 9, 14) regarding the safety of self and others. This is likely to be a consequence of newly formed beliefs that the self is vulnerable, and abuse is prominent (1, 10, 13, 16).

The sense of naivety previously mentioned provides a context in which feelings of shock (1, 11, 13) and disgust (14) are heightened as an increased awareness of trauma shakes their previously held belief system (3–4, 8, 13–14, 16). Some therapists reported feelings of guilt (14), possibly due to the realisation that they are one of the lucky ones. Frustration (1, 9, 11, 16) and irritability/agitation (7, 9, 14, 16) were experienced, which is possibly linked to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness about not being able to change what the client has been through (2, 11, 16).

There is a real sense of these emotions being overwhelming (6, 9, 13), draining (8) and difficult to control (9, 16). Possick et al. (Reference Possick, Waisbrod and Buchbinder2015) refer to the notion of emotional heaviness and resulting turmoil that therapists experience when engaging with trauma survivors. They proposed that identifying one’s own vulnerabilities in a client can mean that a therapist’s work becomes all-consuming – intruding on and infiltrating their personal life. Therapist’s described ‘carrying [a client’s] suffering around with [her]’ (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Cann2005; p. 248), experiencing intense anxiety when at home (2) and ‘carry[ing] feelings home from work’ (Killian, Reference Killian2008; p. 35).

To protect themselves from further distress, some therapists described feeling detached/disconnected/dissociating (1, 7, 9–10, 13, 16), desensitised (4, 8) and ‘shut down’ (Killian, Reference Killian2008; p. 35) following repeated exposure to trauma narratives. Some therapists spoke about difficulties with emotional intimacy because of hearing about trauma (13). There is a sense of ‘[not having] any more to give’ (Killian, Reference Killian2008; p. 35) and being burnt-out.

Some therapists experienced positive emotions from engaging with trauma survivors. There was a sense of pleasure derived from witnessing and being involved in a client’s recovery (1–2). One therapist highlighted how an awareness of strength and resilience enabled her to regulate her own emotional experiences (15). Therapists reported increased levels of compassion (1, 4), empathy (1) and sensitivity (1, 13).

Physiological experiences

Some therapists presented an image of total exhaustion. Language such as ‘weariness’, ‘fatigue’, ‘tiredness’, ‘exhaustion’ and ‘lack of energy’ were used when describing the impact that working with trauma survivors has on the body (1–2, 7, 9, 13, 16). There is a real sense of the work taking its toll with symptoms such as pain, nausea, dizziness/light-headedness, headaches/migraines, muscle tension/soreness and breathing difficulties (including asthma) being described, many of which had no medical cause (1–2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16). The impact on the body was further exacerbated when progress was slow (12). This image of an exhausted state is not surprising given the sleep disruption reported by some therapists (2, 4, 7, 9, 16). Emotions were sometimes expressed outwardly through tearfulness (2, 11, 13), perhaps as a way of discarding excess emotions.

There is also a sense of being on guard or ‘on edge’ (Baker, Reference Baker2012; p. 5) with increased hyper-vigilance and hyper-arousal being reported (2, 7, 16). This is unsurprising given the shift in worldview discussed earlier in the paper. This implies that therapists remained vigilant to potential threat as they constructed new schema around the behaviour of others, the danger in the world and their vulnerability within it.

Cognitive experiences

Therapists’ cognitive experiences were influenced by their newly formed beliefs about the self as vulnerable, others as dangerous and the world as unsafe. Cognitive experiences in this section reflected the therapists’ ‘in the moment’ thought processes or intrusions on their personal life. Witnessing the growth and resilience of trauma survivors had a positive impact on therapists’ thoughts about their own difficulties, life, trauma survivors and their professional work.

Intrusions

Some therapists reported thinking about their clients outside of work hours, especially sessions that had been challenging (2). Many of the therapists reported that they experienced intrusive thoughts, images and nightmares about their client’s trauma (1–4, 7, 9, 13–14, 16). Possick et al. (Reference Possick, Waisbrod and Buchbinder2015) described how this imagery flooded, intruded and infiltrated the therapist’s personal life. There is a sense of re-playing the trauma in one’s own head as if it is in real time and not being able to get it out of one’s head (2, 9). This had an impact on therapists’ ability to be intimate with their partner (9, 13). Conversely, intimacy can trigger memories of trauma reported by clients (9). Possick et al. (Reference Possick, Waisbrod and Buchbinder2015) discussed how therapists struggled to maintain the boundary between their personal and professional lives which made them feel like they lacked control.

Experiencing such imagery is likely to reinforce therapists’ beliefs about the world being unsafe and hostile. It is therefore unsurprising that suspiciousness or paranoia was present for some individuals (2–4, 13–14, 16). This presented as hyper-vigilance and hyper-arousal (2, 7, 16) with some individuals questioning their own personal relationships (8, 13) due to mistrust of others (2, 14, 16).

Some therapists described confusion (7) and forgetfulness (9) as consequences of working with trauma. Pistorius et al. (Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008) identified a sense of dread experienced by some therapists where they hoped that clients would not attend their appointments or experienced relief when they cancelled. One therapist reported that they do not want to hear about trauma so they do not ask for details (Pistorius et al., Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008). These experiences suggest both a conscious and an unconscious desire to avoid exposure to traumatic material.

Altering perspectives

There was a reduced level of optimism (1) and therapists reported feelings of hopelessness (6–7, 10–11, 14), helplessness and powerlessness (1–2, 12, 14, 16). This is potentially due to an awareness of the limitations of therapy in changing what has happened to their clients (6, 11, 13) as well as clients making slow progress (2).

However, there was a sense of hope and optimism which developed from witnessing trauma survivors cope and thrive (1, 3, 5–7, 10, 12, 14–16). Some therapists found witnessing clients’ recovery rewarding (2), particularly their involvement in facilitating that change (3, 8, 10, 15). There were renewed beliefs in the therapeutic process (6, 10, 15) and motivation to support survivors in their recovery (5–6, 13–15).

Witnessing survivors overcome adversity and heal enabled therapists to put their own difficulties into perspective and prompted them to address such difficulties (4–7, 15). Some therapists described increased gratitude for their own lives (1, 3–4, 13, 15–16) which enabled them to consciously make choices to live life to the full (1, 13). Some therapists described being less judgemental (4). Admiration and respect for survivors of trauma was evident (3, 5, 7, 15).

Behavioural responses

This theme represents the behaviours displayed by therapists engaging with trauma survivors. Therapists were reported to pull away from others or express a desire to protect their loved ones. Positive consequences of engaging with trauma survivors included appreciation of others and their own life as well as behaving in ways to promote this.

Most therapists expressed a tendency to pull away from others or a desire to protect their loved ones. Pulling away from others through avoidance (1–2, 13) and isolation (2, 13) was evident. This included not wanting to talk about work (13) and avoiding intimacy (2, 8, 13) due to feeling drained after a day’s work. The desire to pull away from and isolate the self from others appeared to be rooted in therapists’ decreased ability to trust others (2, 8). One therapist highlighted losing faith in her religion and leaving her church (12). The newly formed belief that the world is unsafe affected on the behaviour of therapists (8). Hyper-vigilance was evident (2) with therapists presenting as over-protective of their own children (8, 10, 13) and taking measures to ensure the safety of loved ones (13, 16).

Some therapists viewed having an increased awareness of their vulnerability as positive in that it enabled them to live their own life to the fullest and appreciate the people in their lives more, as life can change at any given moment (1, 4, 13, 15–16). Some therapists spoke about treating others with kindness and respect because of engaging with trauma survivors (1, 13, 15), and others spoke about being more emotionally expressive (1) or thoughtful and attentive (3). Some therapists reported better communication with their children (13). Therapists were grateful for their own lives (1, 3–4, 13, 15–16) and were more motivated to address their own difficulties (5–6, 15).

Discussion

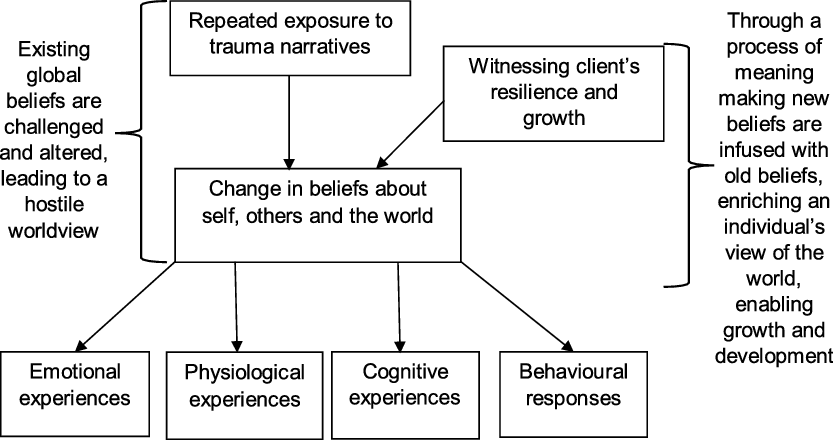

This paper examined existing qualitative literature with a reasonable degree of integrity and synthesised the original themes, extracting quotes to support new interpretations. The themes identified suggest a cognitive model of vicarious trauma and growth whereby therapists presented with cognitive, emotional, physiological and behavioural ‘symptoms’ due to marked changes in schemata following repeated exposure to trauma.

The complex and profound experience of working with trauma

This review presents a profound picture of the impact of working with trauma. Marked changes in beliefs about the self, others and the world can be evident (Bride et al., Reference Bride, Radey and Figley2007; Pearlman and Saakvitne, Reference Pearlman and Saakvitne1995). Therapists could view themselves as incompetent and vulnerable, others as dangerous, untrusting and ‘predatory’ and the world as unsafe and unfair. This may challenge previously held belief systems (Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1992). Armed with this new knowledge, therapists can act in ways to enhance the safety of self and others. The exhaustion of hearing about trauma can be outstanding, taking therapists on an overwhelming emotional, physical and never-ending journey as no matter what they do they cannot remove the trauma history. This can become internalised as personal failure, thus strengthening the belief that they are incompetent and further exacerbating their exhaustion.

Trauma material can infiltrate the therapist’s personal life and may reinforce their view of the hostile world. Therapists can be left feeling drained and like they cannot escape. To stay safe, therapists can detach from the emotional content, perhaps as a way of avoiding engaging with difficult material (Baranowsky, Reference Baranowsky and Figley2002). For some therapists they could develop schemas that separate the perpetrators from the victims. This appears to enable the therapist to separate themselves from the unsafe world (i.e. they are neither perpetrators nor victims) yet ensures that they remain vigilant to its presence (i.e. just in case they become positioned as one). Additionally, it is possible that the thought of somebody being both a victim and a perpetrator, challenges therapists’ view of the world which is why they may attempt to distance themselves from this notion. The papers in this review did not appear to consider how the experience of vicarious trauma ‘symptoms’ might have an impact on the quality of the therapy provided to clients.

Cohen and Collens (Reference Cohen and Collens2013) proposed that the experience of vicarious trauma and post-traumatic growth occurs through empathic engagement with trauma narratives. They purported that helpers experience shock from their client’s adverse experiences or their remarkable strength and resilience. Their paper suggests that therapists go through a process of meaning making as these experiences challenge their existing global beliefs and as such a cognitive shift is experienced. These authors reflected on how positive and negative changes to the helper’s belief system can occur and drew on the work of Joseph and Linley (Reference Joseph and Linley2008) in making sense of this, i.e. that the self is multi-faceted and can thus integrate both positive and negative aspects. Adding to this understanding, Linley et al. (Reference Linley, Joseph and Loumidis2005) proposed that as new beliefs are infused with old beliefs, the therapist can experience growth and development because their understanding of the world is enriched.

Some individuals experienced a positive shift in their cognitive schemata which appeared to have important implications for their cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses in their personal and professional lives. There appeared to be a sense of strength and a recognition of their own abilities through witnessing the resilience of trauma survivors. Pearlman and Saakvitne (Reference Pearlman and Saakvitne1995) proposed that growth occurs when helpers are inspired by their client’s ability to survive adverse experiences. Social learning theory appears relevant here whereby therapists bear witness to growth and incorporate this into their own experiences (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977).

Therapists may find trauma work rewarding, particularly when they view themselves as having been a part of their client’s growth. Bartoskova (Reference Bartoskova2017) proposed that as confidence increases, the level of self-doubt plateaus as therapists begin to see the impact of trauma work. Bearing witness to recovery may also affirm therapists’ commitment to their work as well as their belief in therapy. Seeing the self as more vulnerable may prompt therapists to live their life more fully and appreciate their loved ones more (Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996).

Therapists may be able to alter their view of others as either victims or perpetrators of adverse events, to develop a more nuanced, compassionate, optimistic perspective which is more in keeping with their profession, i.e. formulation driven. Being aware of others suffering may enable therapists to contextualise their own difficulties and witnessing client resilience could prompt them to take action. For some individuals there may be an increase in emotional connectiveness and gratitude for their own fortune. Building on the ideas of Cohen and Collens (Reference Cohen and Collens2013) and the findings of this review, a cognitive model of vicarious trauma and growth is outlined in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Cognitive model of vicarious trauma and growth

Clinical implications

An awareness of the adverse effects of trauma work is important given that containment is an important aspect of therapy (Edwards, Reference Edwards2009; Pistorius et al., Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008). Existing research outlines the potential impact of vicarious trauma on the therapeutic relationship (Herman, Reference Herman1992; Pistorius et al., Reference Pistorius, Feinauer, Harper, Stahmann and Miller2008) and therefore the findings strengthen the argument that employee well-being should be prioritised, in line with government recommendations (Stevenson and Farmer, Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017). It would be beneficial to open up the dialogue about vicarious trauma and its effects through clinical supervision, training and reflective practice given the reported internal changes that occur. It may also be possible to develop a programme of active reflection relating to vicarious trauma within format training where therapists can openly share their experiences and strategies to manage their experiences so that experiences can be shared effectively.

An important finding of this review was that some therapists experienced their own growth through being involved in their client’s recovery. This can moderate against thoughts of self-doubt (Bartoskova, Reference Bartoskova2017). A system-led approach around strength and resilience can further facilitate growth and development in helpers. Introducing a narrative around what is going well could become more integrated in the ethos of organisations providing support to trauma survivors.

Limitations

This review included papers of a reasonable quality which were assessed using NICE’s (2012) guidance on quality appraisal. Some of the papers that were included in this review were on the cusp of good quality and may have reduced the reliability of the findings. However, one could also argue that excluding papers deemed poor quality may have meant that important findings were missed that may have altered the results and provided alternative perspectives. Thus the 16 articles that were included provide an understanding of some therapists’ experience of their work with trauma survivors; it is unlikely to be representative of every therapist who works with trauma. There was also some variation in the qualitative methodologies used within the papers reviewed that may have led to variations in the results of the papers that could not be controlled for.

Additionally, although a systematic search strategy was adopted it is important to acknowledge that there may be relevant articles that were not identified due to some of the criteria that outlined what was suitable for inclusion. For instance, articles that were not peer reviewed did not include participant quotes or had less than 75% of therapists included in the sample were excluded. These articles may have provided an alternative perspective to the experience of working with trauma.

The type of review selected for this paper relies on the interpretation of the original findings as well as new interpretations by the researcher. This means that there is a level of subjectivity inherent in the methodology utilised. The analysis was reviewed on several occasions within supervision to increase the reliability of the review; however, the qualitative paradigm means that potential bias is always present. It is possible that our personal views of the world may have affected the way the data were interpreted. For instance, cognitive behavioural therapy is our preferred model of working. This is likely to have guided our thinking when synthesising the data and may have prevented a more objective stance.

It is important to note that this review explored the nature of vicarious trauma but concepts such as burn-out may also be helpful in increasing our understanding of some of the themes identified. A related issue is that of personal trauma that may be experienced by individual therapists outside of their work setting; while it would have been interesting to explore this phenomenon, it was considered that it would make the results of the review difficult to interpret and summarise concisely. It would be useful to explore the inclusion of these phenomena and how they differ from vicarious trauma to fully understand the potential impact of working with and experiencing trauma.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000776.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Natalie McNeillie and John Rose have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethics statement

This paper did not require ethical approval as it is a review of existing literature.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.