1. Introduction

The goal of this article is to diagnose a construction based on the verb gehen (‘go’), a particle, and the reflexive, which has made it into common use in Austrian German:

We will situate this construction in the landscape of modal and ‘go’ constructions and we will propose that its semantics is based on measurement as a sufficiency construction. Semantically, sufficiency involves modality and implicativity, and we will see that the present construction is no exception (classical implicative is a predicate the complement of which holds true not only in possible worlds but in the actual world, e.g., manage). However, recent studies have adduced strong theoretical evidence that modal and implicative expressions are more diverse than classically thought (see Hackl Reference Hackl1998, Bhatt Reference Bhatt1999, Piñón Reference Piñón, Garding and Tsujimura2003, Hacquard Reference Hacquard2006, Rullmann et al. Reference Rullmann, Matthewson and Davis2008, Yanovich Reference Yanovich2013, Gergel Reference Gergel, Rivero, Arregui and Salanova2017, Nadathur Reference Nadathur2017). A question from a historical perspective is what the sources for such items are. Another issue is what modal trajectories look like. Yanovich (Reference Yanovich2013), for instance, argues that in the case of the Old English modal motan (‘be able to, must, etc.’) a more intricate entry is required than previously thought. Going further back, the Oxford English Dictionary indicates a reconstructed connection of motan to measurement (‘to have something measured out’), but reconstructed sources for very old modals make it hard to ascertain their source construction with semantic precision. We will see that our construction also shows a potential connection to measuring entities out, even if, as we will argue, the diachronic trajectory it underwent is quite distinct. Similarly, in view of modal analyses (e.g., Kratzer Reference Kratzer2012), a relevant issue is the connection between degrees and modality, and sufficiency is an area in which degrees and modality have been recognized to interact for some time (Meier Reference Meier2003). Thus, it may be worthwhile to expand the empirical inventory. This background motivates our enterprise from a larger perspective.

In section 2, we will describe the basic morphosyntactic ingredients and the main semantic characteristics involved. In section 3, we will present the results of our corpus research, before moving on towards an interpretation of sich ausgehen in section 4. Section 5 discusses the Austrian German construction against the backdrop of some similar constructions in German and beyond. The potential role of contact is discussed.

2. Properties of sich-ausgehen (SAG) Constructions

In this section, we lay out the minimal descriptive basis for our understanding of the SAG construction.Footnote 1 The construction finds routine mention in dictionaries and lexical collections of German Austriacisms (Ebner Reference Ebner1998, Sedlaczek Reference Sedlaczek2004, Dürscheid et al. Reference Dürscheid, Elspaß and Ziegler2018). We will begin by pointing out some of its diatopic and morphosyntactic distributional properties in section 2.1, continuing in 2.2 with a further contextualized description of the modal flavours and possibilities of scales involved.

2.1 Distributional and morphosyntactic properties

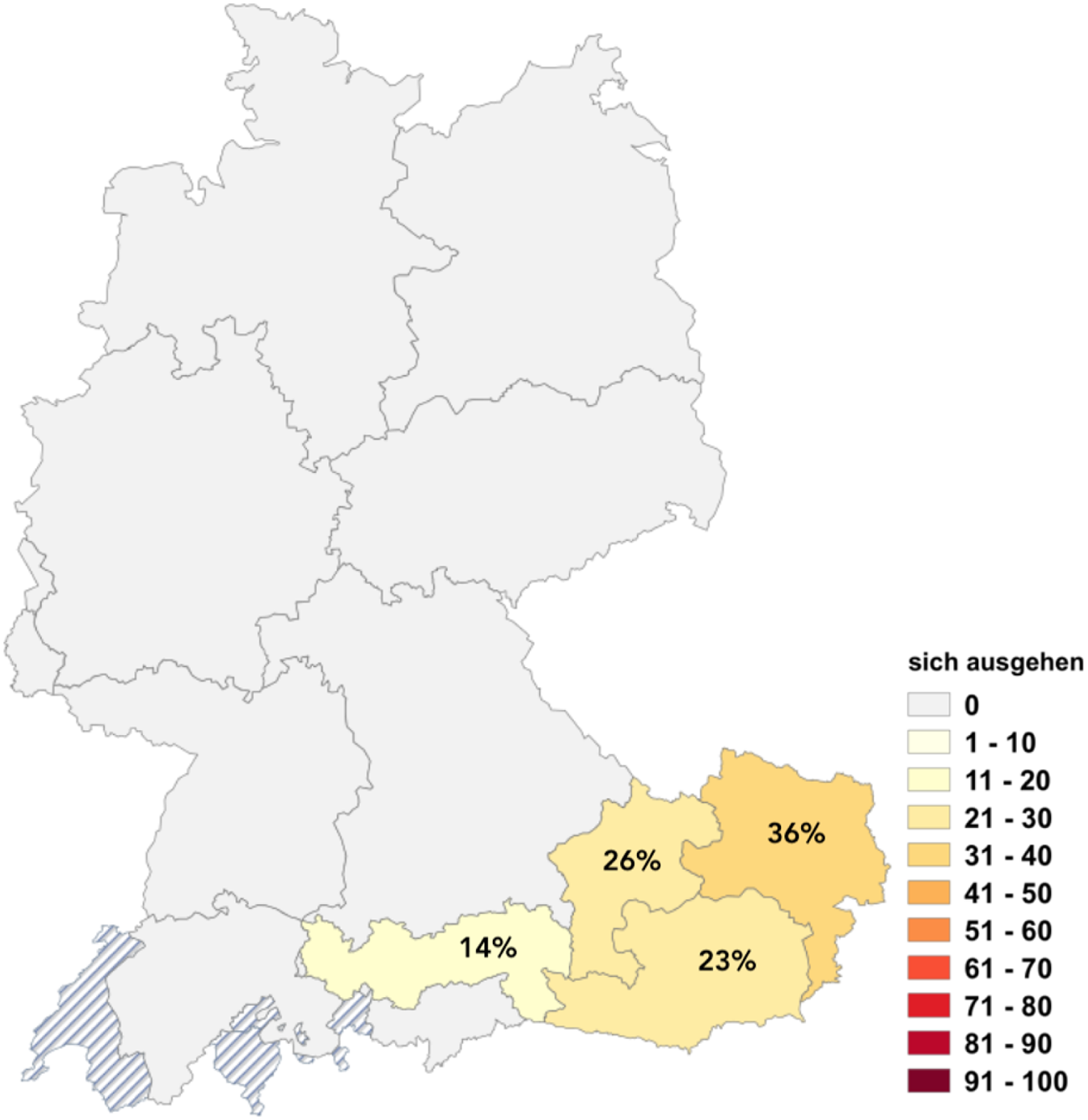

The construction under discussion, which we will abbreviate on the basis of its morphemes as SAG (‘sich ausgehen’), is available in all current Austrian states. According to some descriptions, it is not available in Federal German (see Dürscheid et al. Reference Dürscheid, Elspaß and Ziegler2018).Footnote 2 For the less familiar reader: Austrian dialects belong to the family of Bavarian with the exception of the dialect spoken in the federal state of Vorarlberg, which belongs to the Alemannic family. The Austrian branches of both families have the construction; see Fig. 1. The purpose of this figure is merely to give a synchronic orientation. The numbers do not amount to 100% due to rounding errors; the nine federal states of Austria are grouped into four ‘regions’ on a basis that is neither political nor dialectal (e.g., Alemannic and Bavarian dialects are lumped together). As to the overall frequency of SAG in Austrian German: a 1% randomized sample of the Austrian Newspaper Corpus (Österreichisches Zeitungskorpus, a subpart of the DeReKo spanning the years 1991–2018), yielded 126 SAGs, a frequency of 0.00107%.

Figure 1: Areas of occurrence of SAG in Present-Day German (Dürscheid et al., Reference Dürscheid, Elspaß and Ziegler2018)). Austria is divided into four ‘regions’ which have neither a political nor a dialectal basis. For instance, 36% for the Northeast, which includes Vienna, means that 36% of all SAG examples in the sample are from that region.

Conversely, specialized dialectal works written from the perspective of Austrian German dialects do not mention SAGs, as they belong to the common inventory of Austrian German (Eckner Reference Eckner1973, Haasbauer Reference Haasbauer1973, Hutterer Reference Hutterer1987, among others).

Syntactically, SAGs exist in two major patterns in Austrian German. The first type takes a nominal subject in the nominative as its only argument and was introduced in (1). We refer to this type as nominal. The second major pattern involves a clausal (and typically finite) complement. Hence this type involves a dass ‘that’ finite complement clause. So in addition to the version in (1), an alternative as in (2) is available in the same context:

The slightly more abstract syntactic patterns are, then, as follows:

(3)

a. Subject nominal + SAG (example (1))

b. Dummy-pronoun-subject + SAG + that-clause-CP (example (2))

The nominal pattern involves opportunity relating to an event built around the nominal subject (e.g., ein Kaffee, ‘a coffee’ in (1)). We call this type of nominal the key; we will return to a semantic property of the key in the next subsection. The clausal pattern seems more transparent, in the sense that it has a proposition-denoting syntactic complement to the SAG. It contains, for example, an overt verb in the complement (‘drink’ in (2)), something that needs to be reconstructed in the nominal variant. However, as we will discuss in section 4, both patterns are underspecified from the perspective of compositionality.

Despite the relative poverty of overt building blocks, Austrian speakers across the board report temporal judgements for sentences such as (1) and (2) (see also the local, i.e., sentential context set up, including an appointment and the preposition vor, ‘before’ – but neither is obligatory). By temporal judgements, we mean temporal sufficiency judgements (i.e., ‘there is enough time’), and not temporal in the sense of shifting or quantifying (as in tense semantics). We will also discuss environments different from time, but the key point is that some scalar notion is involved in all of the examples that we found.Footnote 3

Some speakers – without being asked about this property – also comment that there is not much time left, that there would not be time for two cups of coffee, etc. This component of meaning, however, is not obligatory in all cases. If the context is slightly changed, then the inclusion of other modifiers such as gut, locker and others. ‘well, easily, etc.’ can easily retract the implicature.

We will focus on the two typical patterns of the construction, which can convey similar notions, with the nominal pattern doing so in an informationally more dense way (Shannon Reference Shannon1948). However, to some extent (less idiomatically), it is also possible to have infinitival zu, ‘to’ complements in SAG constructions. These feature an obligatory expletive es, ‘it’, in the matrix clause (i.e., control structures are excluded; see issues in the literature related to raising vs. control status of can and other modals in Hackl Reference Hackl1998, Reis Reference Reis, Müller and Reis2001, Wurmbrand Reference Wurmbrand2001, Gergel and Hartmann Reference Gergel, Hartmann, Alexiadou, Hankamer, Nugger, McFadden and Schäfer2009, among others).Footnote 4

The modern patterns we have looked at are, semantically, largely equivalent. For instance, the nominative argument in the clausal pattern (often this is the beneficiary for whom the opportunity holds) can be introduced in the nominal pattern as well. But this then happens through obliques, for example as a dative, or via prepositional phrases (illustrated with bei, ‘at’ below – but other prepositions are also possible, e.g., für).

There is, furthermore, a wide range of possible context setters in SAG constructions. For instance, explicit inclusion within the range of in-phrases is possible:

While the range of morphosyntactic possibilities in SAGs is large, there are also syntactic restrictions. For instance, the nominal (car) in (7), below, around which the event (parking) is built in the embedded clause, cannot be made a clause mate of SAG while keeping the finite complement clause and taking up the entity of the noun either resumptively or as a potential trace in the embedded clause, as in (8):

Another relevant distributional restriction is that SAGs do not take progressives. More pedantically, they do not take progressive periphrases, as there are no morphological progressives in German. First, independently of SAGs, neither the verb go, nor particle verbs, nor reflexives block progressives. The degree to which progressives are grammaticalized as functional markers can be debated and more variation and interesting issues exist (see Ebert's Reference Ebert and Dahl2000 overview of Germanic), but for our purposes the very existence of a form from the imperfective family should suffice to make the descriptive point, see (9)–(10):

When it comes to SAGs, however, progressives are ungrammatical:

The restriction on the progressive cannot be blamed on incompatibility of SAGs with tempo-aspectual inflectional morphology (as, for example, in the Modern English modals). Both the preterite and the perfect form licit inflectional paradigms with SAGs:

We will return to this restriction on progressives in section 4.

2.2 Further meaning coordinates

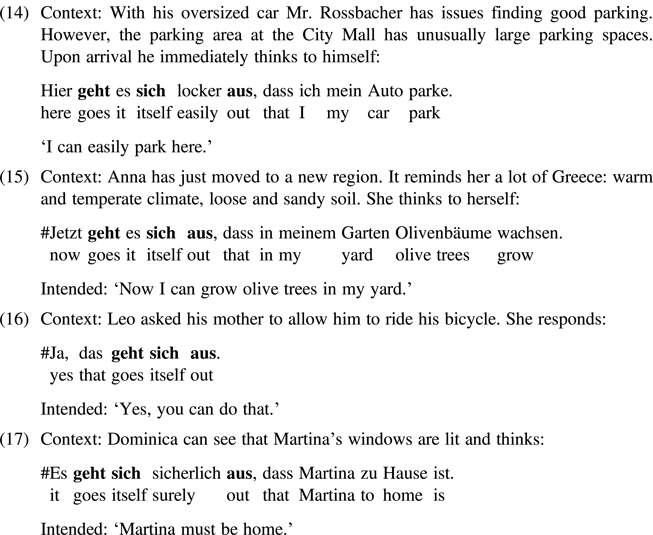

From the examples inspected, a first impression emerges that a notion of modal opportunity is involved. This is, however, far more restricted than the nuances expressed by other types of possibility core modals such as those familiar from English or German. First, neither laws, regularities, permissions, nor states of affairs related to knowledge or evidence (sources) yield felicitous modal readings for SAGs. That is, deontic or epistemic readings cannot be construed for SAGs. An example such as (1) or (2) presented above is perfectly natural on a reading involving the circumstances and the background of the amount of time available. But it cannot be interpreted in terms of permission or some type of evidence pointing towards having a cup of coffee. Furthermore, even a sentence such as (7), which appears to bias the context towards a deontic reading, cannot be interpreted deontically. Rather, the statement is interpreted as asking for information regarding whether the space available in the parking spot will suffice for parking. We offer additional contextualized evidence to illustrate our claims. An example such as (14) is licit, while examples like (15)–(17) are not:

What the examples above show is that on the intended circumstantial (15), deontic (16), and epistemic (17) readings induced by the respective contexts, SAGs are not licensed at all in current Austrian German. However, some ambiguities can still arise with SAGs. Recall our parking example in (7) repeated here as (18):

The interpretations available for (18) are all related to scales. For instance, are our schedules compatible (time), are space and shape issues solved, etc.? This means that, although there is room for ambiguity in this construction, it usually involves the type of scale, and not, for instance, the modal flavour (say, epistemic vs. deontic).

Further scales can appear in SAGs; here are just a few examples:

The available readings are that the range of a car, the points in a competition, and the money allotted for overdraft, respectively, are sufficient. The relevant restriction for SAGs then becomes apparent with respect to a scale. Licensors can be time, volume, two- or three-dimensional space to park, the range of a car, points achieved in a competition, amount of money on an account, etc. Sentences intended with a purely circumstantial reading that do not offer an immediate interpretation in terms of scales/degrees garner low average acceptability (see the results of a (relatively) informal elicitation experiment in appendix C).Footnote 5

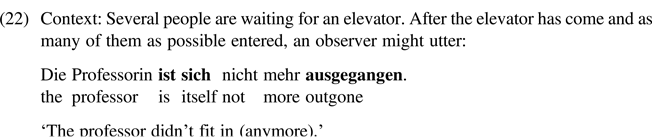

Having noted the restrictions with regards to modal flavours and scales, we conclude this section with an additional generalization regarding SAG subjects. In the clausal pattern, the subject is an expletive and the complement proposition is expressed in the embedded clause, from which there is not much possibility of relocating material into the superordinate SAG clause. However, something particular can be said about the apparently more fragmentary nominal pattern. The generalization we suggest for it is as follows. The nominal argument (ein Kaffee, ‘a coffee’ in (1)), that is to say, the key, is an entity that is causally affected by an event which must usually be reconstructed contextually – for instance the drinking event, in the case of a cup of coffee. Notice also that this is not a restriction based on non-animacy of the nominative argument, but one that has to do directly with its strict character as an entity that is causally not acting in any way. All of the examples of SAGs shown so far illustrate this fact, but they could also be interpreted in terms of a non-animacy constraint. Therefore consider (22):

Example (22) shows that it is possible to have an animate nominative subject. But then the interpretation cannot be that the professor acted in a particular way or brought something about, but rather (and only) that she could not fit into the space available in the elevator and was thus caused to remain outside. Thus, in a construction which seems to be otherwise fragmentary on multiple levels, the only obligatory argument (as far as the nominal pattern goes) is the key, which encodes a relatively specific causal participant (the current suggestion being that this is a causee); see section 4 for the relevance of causation in the current context.Footnote 6

3. Diachronic attestations

Section 3.1 describes our methods and sources, and subsequently illustrates the main types of examples detected. We make a distinction between genuine or prototypical SAGs, presented in section 3.2, and candidates for being proto- or pre-SAGs in section 3.3.

3.1 Methods, sources, and searches

The overall goal of our research was to identify relevant form-meaning pairings and interpret them against the backdrop of the contexts available. Specifically, we searched for constructions that had the formal ingredients of SAGs (i.e., the motion verb, the reflexive, and the particle), but for which a compositional interpretation of ‘going out’ in some sense or another, was unavailable. This in turn meant that we either (i) ended up with a SAG or (ii) with what we define as a pre-SAG, that is, a construction which is not acceptable in current Austrian German, but which can still not be computed compositionally on the basis of the overt items as they stand. The term pre-SAG is used in this purely predating sense and without any teleological implication that (any of) the precursors had to yield SAGs. From earlier corpus studies (e.g., of those reported and compared in Gergel and Beck (Reference Gergel and Beck2015: 37ff), Gergel et al. (Reference Gergel, Blümel and Kopf2016: 113 ff)) we knew that readings (including ambiguities and readings that do not exist today) can be empirically determined in a productive way on the basis of context. In fact, the identification of meaning on the basis of context was, comparatively speaking, a rather easier task than normal in the present case, and we describe the two major groups of meanings found in the next two subsections. The key difference between the present study and the studies just cited, however, was that no appropriate corpus that was large enough to produce hits was available, much less a parsed one. For single items such as again, noch, ‘still’, or motan, ‘can/must’ (see Beck et al. Reference Beck, Berezovskaya and Pflugfelder2009, Kopf-Giammanco (to appear), and Yanovich Reference Yanovich2013, respectively), the issue of whether a parsed corpus is used or not is secondary (unless one is specifically interested in testing correlations with structure; see Gergel Reference Gergel, Rivero, Arregui and Salanova2017). But given that we are dealing with a construction, and not a single lexical item, the task of SAG-identification faced difficulties. There is, for instance, no lemma or corpus notation that would identify a SAG as such and the three ingredients are all frequent items. A number of sources and strategies were therefore pursued in mining for diachronic data; we describe the most prominent ones in the remainder of this subsection.

First, our main focus was to trace the construction in time. Hence we did not concentrate on a corpus study of present-day language, but rather on data from the past. Our main sources primarily contained data from prior to WW2.

Within the German Reference Corpus Deutsches Referenzkorpus (IDS, 2018), via the COSMAS II web application (IDS, 1991ff), the HIST Archive, which covers the period from 1700 to ca. 1918, and contains 66.58M word forms, was used to gather this diachronic data. This search for SAGs yielded a list of 1,887 potential hits which, after manual review, all turned out to be false hits. Another effort was made in the W Archive, another subcorpus of the DeReKo, which contains 9.89M word forms and includes literary fiction from the 20th and the 21st centuries. Our search yielded 452 potential hits, two of which were SAGs (unfortunately – from a diachronic perspective – from 2009 and 2011).

The Early New High German Corpus Bonn (Bonner Frühneuhochdeutsch Korpus, cf. Korpora.org) covers the period from 1350–1700, contains 300,000 word forms, and includes Viennese-based texts. Yet no SAGs were found in that corpus. Other attempts at finding historical SAGs included text searches in Project GutenbergFootnote 7, the Internet ArchiveFootnote 8, Google Books, and in various Google searches. Additionally, we targeted historical magazines and journals such as Die Fackel, MAK-Hauszeitschriften, etc. Further targeted text searches in writings of Austrian authors (largely fiction) also failed to yield any SAGs.

The most useful resource proved to be the ANNO (AustriaN Newspapers Online cf. Austrian National Library) corpus published and continuously updated by the Austrian National Library. A number of methodological issues arose. The interested reader can consult Appendix A for details in our various searches in the ANNO Corpus. The most telling data are presented in the next two subsections. Before setting out examples, let us note that we found a total of 120 strict SAG examples, and a superset of 168 examples which included pre-SAG constructions, the specifics of which we discuss in section 3.3. The diachronic development in the frequencies of the examples we have observed is rendered in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Frequencies relative to the overall number of wordforms per decade in the ANNO corpus; SAGs (pre-SAGs excl.) (%); detailed numbers in Table 3

Figure 3: Frequencies relative to the overall number of wordforms per decade in the ANNO corpus; SAG and pre-SAG constructions (%); detailed numbers in Table 3

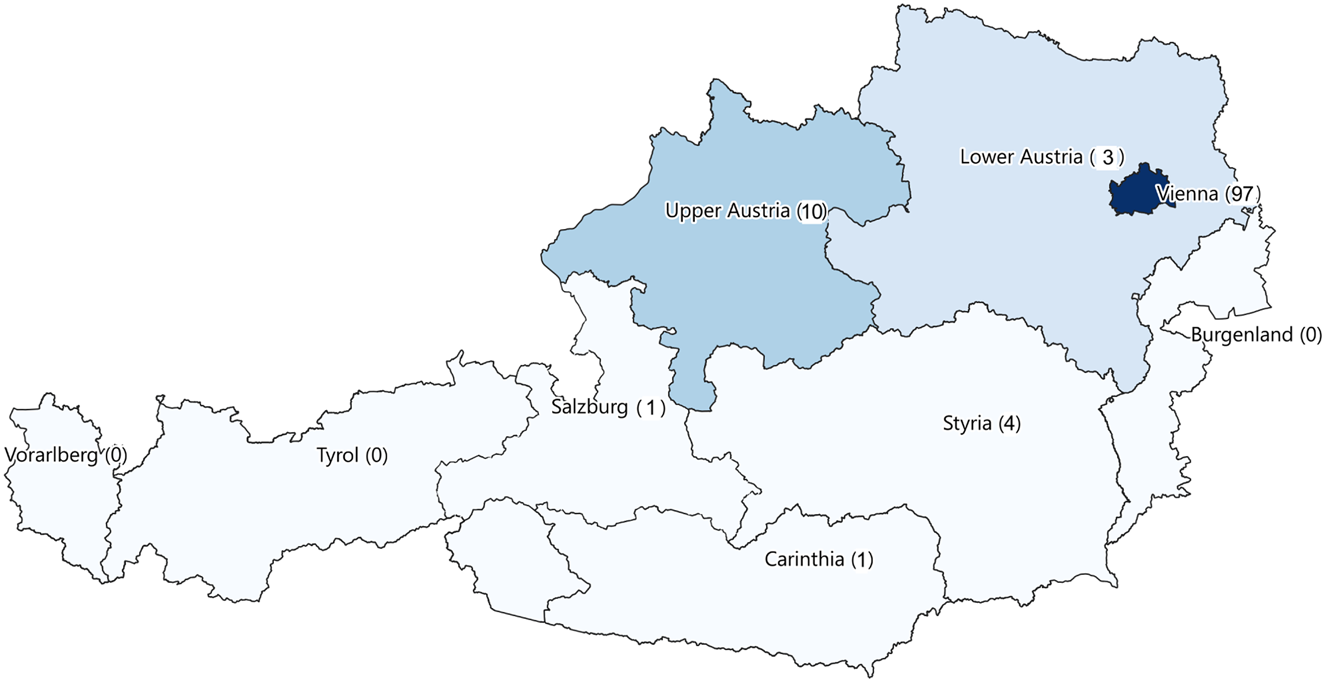

From a diatopic point of view, the SAG examples have been identified in the regions of Austria given in Figure 4. We use the current map of Austria for simplicity. We did not find SAG examples in territories outside the current state (although there was one pre-SAG construction from Bohemia).

Figure 4: Diachronic SAG occurrences in Austria based on current ANNO findings; for map data cf. Perlot (Reference Perlot2017) and compilation cf. QGIS Developer Team - Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project.

Figure 4, which includes only the genuine SAGs and not its precursors (see the two following sub-sections for more information on the distinction) seems to suggest a Viennese concentration and perhaps origin, and a spread westward. The caveat is, of course, that the majority of the newspapers in the corpus originate in Vienna (see Table 4, in Appendix A).

3.2 Diachronic SAG examples

The present subsection offers an overview of the patterns of genuine SAG examples, based on the searches described above and in appendix A. An interesting use of SAG, that is, one which already shows properties available in current Austrian German, is rendered in (23):

An earlier SAG example based on a monetary scale is (24), while the even earlier SAG in (25) from 1888 features a width scale.

Temporal scales also feature prominently in the early SAGs, as the following example from 1883 shows:

The examples in (23)–(26) can be understood and recognized as SAGs by current speakers. Moreover, they introduce degrees and a sense of sufficiency measured in various scales. The scales are unspecified monetary units, crowns, hand widths, or days. Interestingly, some of the examples also appear in contexts in which dialogues are reproduced or with the relevant motion verb in quotation marks. We cannot (and do not wish to) claim that this is theoretically or numerically sufficient, given the scarcity of the examples. But since the examples seem to appear in orally-flavoured contexts, this may offer a hint as to why they have been harder to find in written sources.

The following examples show scales such as number of fingers, beers, and time:

We end this subsection with another example based on a time-scale. Note, at the same time, that the example offers multiple positive contextual clues, that is, it allows more than one reading:

On the one hand, (30) contains temporal clues such as getting the work done within an hour and keeping track of time. But the candle and the pendulum could literally go out or turn off. While such a use of ausgehen would not feature the reflexive in modern varieties, reflexive uses appear to be more common in the 19th century, so that theoretically, another reading than a SAG could also obtain. Yet another interesting reading is one of suitability or compatibility. In this case, the desires of the subject and the projected course of all relevant events (via Alles, ‘all’) are viewed as compatible. We think such readings are some of the potential precursors of SAGs, to which we turn next.

3.3 Pre-SAGs

In this subsection, we present examples that do not have the narrow semantic properties of the SAGs described in section 2, but which – after inspection of all contextual factors available – do not have either (i) a literal and compositional meaning of gehen (‘go’), aus (‘out’), and sich (‘itself’/refl.), or (ii) the meaning of another (reflexive) verb-particle construction that is available to us from present-day German. While we call these constructions pre-SAGs, notice that as a set, they do not all temporally precede all occurrences of genuine SAGs. This should not be too surprising for historical linguists, but is worth keeping in mind when dates are considered (recall also the overviews in Figures 2 and 3 above).

Example (31), like the previous ones, mimics direct speech; it can also be viewed as degree-based, since money is involved. But its pragmatics, at least at face value, is distinct from what would be licensed today. The meaning ‘It's alright’ would (and could, of course) be conveyed in a multitude of other ways. But essentially for conveying ‘You can keep the change’ it would be very puzzling to use a SAG from the point of view of Modern Austrian. A very marginal context that would allow that might be along the lines of ‘I already have just about enough money for a clear goal that is established in the common ground’ and as an implicature, the hearer might be invited to keep the change. But the situation does not license any such inferences.Footnote 9

Another example which shows a (more general) sense of compatibility, and which is also decidedly not acceptable to speakers of Modern Austrian German, is the following:

Unlike SAG examples in the previous subsection, (32) shows appropriateness (or rather lack thereof due to negation), in an eventive context, but it does not make reference to any either obvious or overtly contextualized sense of degrees.

Additional examples, attested in the historical records, are also unacceptable as SAGs in Modern Austrian German:

In example (33), the event anaphorically referred to happens to the detriment of the taxpayers. Examples like (34)–(35) are related to a sense of wearing out. What (33)–(35) have in common, in addition to being neither fully compositional nor acceptable in Modern German, is that they depict undesirable outcomes. This is in a clear and additional counterdistinction to the SAG constructions which express sufficiency. If modern SAGs express a type of sufficiency that additionally presupposes desirability, a topic which we examine in the next section, and one sub-type of pre-SAGs expresses stereotypically non-desirable outcomes, then the question is what an appropriate bridging context may be. Examples like the following, involving the predicate gut ausgehen, ‘go out well’/‘have a positive ending’ are particularly relevant (see also subsection 5.2):

The example in (36) is interesting also because it shows a free alternation between the reflexive and the non-reflexive form of the verb ausgehen.

Finally, we briefly present one more type of example, which – even though the relevant sentences contain neither pre-SAGs nor SAGs – happens not to be used as such in Modern German (whether Austrian or Federal):

Examples like (37) and (38) are, however, very straightforward to understand compositionally. There is a literal walking event (or iteration of such events) on the stairs that causes them to wear out and similarly there are walking events that cause the cattle to get their feet in shape. (Notice that we found the example in (38) outside of ANNO, and that it is simply based on a dictionary entry from an author who was born and died in Saxony, which is to say he was clearly a speaker of a non-Bavarian variety of German.Footnote 10 As we will discuss in section 5, this shows once more that the initial ground for the construction was (unsurprisingly) available in what appears to be all varieties of German, but it must have taken something more for it to develop the modal meanings of the modern SAG (i.e., sufficiency) and pre-SAG type (with appropriateness and compatibility as one major sub-type identified).

To summarize: while it is not difficult to find current attestations of SAGs, issues arise diachronically. This could mean that more research needs to be done, or that the construction is relatively recent. We presume both to be true and repeat the caveat about the oral character of the construction at early stages; and yet newspapers at the time incorporate a fair deal of oral discourse. At this point, we take the construction to be relatively recent, arising in the 19th century. The earliest example we could find which provided evidence for a SAG in the current sense was from 1865. The potential precursors came, naturally, earlier. A particularly relevant meaning within this class of constructions seems to be a general notion of compatibility or suitability.

4. Sags in the landscape of enough constructions

In this section, we situate the SAG construction semantically, by offering additional descriptive generalizations. On the basis of the observations made, we propose a semantics that slightly modifies current suggestions available for sufficiency constructions and enriches them with a further meaning component of desirability.

4.1 A note on more general issues of modality and scale

The empirical generalization from the discussion so far is that SAGs have developed from motion indicators to intensional markers which involve both a restricted sense of modality and, crucially, a scale. SAGs thus represent constructions in which degrees and modality come together, although neither needs to be explicitly mentioned. While several theoretical options are available to connect modals and degrees (see Lassiter Reference Lassiter2011, Lassiter Reference Lassiter2017, Kratzer Reference Kratzer2012, Hegarty Reference Hegarty2016, Herburger and Rubinstein Reference Herburger and Rubinstein2018), the meaning of SAGs lends itself to an analysis in terms of a rather standard approach, namely one couched in terms of sufficiency, that is, enough constructions (ECs) which is orthogonal to the way one normally sees modality. This is not the place to settle the issue of whether modality itself is to be viewed probabilistically, as gradable per se, and related issues.Footnote 11 What we claim at a descriptive level is that the existence and development of SAGs themselves show that degrees and intensionality interact rather closely in SAGs. The same point can be made, of course, with classical ECs, as e.g. von Stechow et al. (Reference von Stechow, Krasikova and Penka2004) do. In the following subsection, we will consider what we take to be the relevant aspects in the panorama of ECs and situate SAGs more specifically there.

4.2 SAG as a sufficiency construction

We propose an analysis of SAGs as sufficiency constructions by approximating them with ECs. We will first point out the main similarities and differences between SAGs and ECs.We then make a proposal regarding the computation of meaning in SAGs by building on suggestions from the literature on enough and too constructions (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971, Meier Reference Meier2003, Hacquard Reference Hacquard, Georgala and Howell2005) and specifically on more recent endeavors that connect such intensional constructions with causality (Schwarzschild Reference Schwarzschild2008; Nadathur Reference Nadathur2017, Reference Nadathur2019, among others). In a nutshell, then, we propose that SAGs are roughly speaking ECs, but with two main differences: (i) they presuppose desirability and (ii) their meaning is computed from the available and implicit building blocks differently.Footnote 12

A first reason to view SAGs and ECs on a par is that both combine degrees and modality. A second, intuitive, reason is that the most natural paraphrases available for SAGs contain expressions of the type ‘the available time/money/space/volume etc. suffices’. Third, just as is the case with enough constructions, a goal appears obvious and necessary for the purposes of interpretation (time available in order to drink coffee, space to park one's car, money available to operate with, etc.). Fourth, SAGs and ECs show implicative behaviour (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971, Meier Reference Meier2003, Hacquard Reference Hacquard, Georgala and Howell2005, Nadathur Reference Nadathur2017). Consider (39):

In addition to conveying that the subjects of the embedded clause had enough time to drink a cup of coffee, (39) implies that they did drink a cup of coffee (in the actual world). The actualistic behaviour in SAGs is in fact even stronger. Thus, while the recent literature has suggested certain exceptions to the actuality entailment of ECs, we have not been able to find, elicit, or produce any non-entailing examples of SAGs at this point. (See Gergel Reference Gergel2020 for a quantitative assessment on the implicativity of SAGs compared to modals and entailments.)

When translating a SAG structure into an EC, a number of differences from the original interpretive effects of SAGs hold. We will translate the SAG, as we thereby hope to illuminate the parallels as well as the differences between these constructions. The closest we can get to a standard EC this way seems to be along the lines of (40):

(40) The time available was long enough for Stefan and his friend Paul to have a cup of coffee.

Let us review the differences in the building blocks of SAGs compared to ECs.Footnote 13 First, the gradable scalar adjective (long in (40)) is not visible in SAGs. Second, the goal is only directly visible as a whole in the propositional variant. We are of the opinion, however, that those differences should not impede an account in terms of sufficiency. We have already noted two things which are strongly available as meaning components. First, the scale is necessary; modalized SAGs of a variety of modal flavours that lack a scale are either infelicitous, or coerced into scalar readings. Second, we have illustrated empirically that the subject in the nominal pattern has a requirement that it be the entity causally affected in an event.Footnote 14 What we assume to be a baseline is the semantics of ECs starting with Meier (Reference Meier2003) and developed further in von Stechow et al. (Reference von Stechow, Krasikova and Penka2004), Hacquard (Reference Hacquard, Georgala and Howell2005), Nadathur (Reference Nadathur2017, Reference Nadathur2019), among others. We do not reproduce its computation here, (i) for space reasons, and (ii) because the way the computation is achieved is different in SAGs. However, we may point out up front that the shared element in most of the literature is a semantics based on a universal modal combined with an equative. The idea behind such thinking is that if there is enough time to have a cup of coffee, the participants have as much time as is required for having a cup of coffee. On a basic level, we also assume a degree semantics, but leave aside the discussion of whether gradable adjectives are functions or relations (see Beck Reference Beck, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2011 for an overview), because they largely represent translatable variants of one another for our purposes, as long as there is agreement that degrees belong to the semantic ontology of natural language. We model our computation relatively closely on that of (Nadathur Reference Nadathur2017, Reference Nadathur2019) and then slightly simplify, correct, and adapt those suggestions for SAGs. The main ingredients we make use of for the meaning computation of SAGs are as follows:

• the scale of a usually implicit gradable expression GRD;

• an entity x;

• a proposition Q expressed either explicitly through the embedded clause in the clausal pattern, or induced via the key in the nominal pattern.

The resulting proposal we suggest for SAGs is given in (41):

(41) Let S be a sentence containing a SAG based on a contextually available gradable expression GRD, a contextually available entity x which serves as an argument of GRD, and Q a proposition which is (as a function of the syntactic type of SAG) either (i) directly introduced by the interpretation function applied to the complement clause sub that is subordinated to the SAG in the clausal SAG pattern, or (ii) contextually induced by the denotation of the key k in the nominal pattern. Then, evaluated with respect to a world w:

a. SAG (and thereby S) presupposes a degree d nec that is necessary for Q:

$$\exists d_{nec}\ \colon \ \forall {w}^{\prime}\in {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{acc}}( w ) [ {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ( {{w}^{\prime}} ) < d_{nec}\to \neg Q( {{w}^{\prime}} ) ] $$

$$\exists d_{nec}\ \colon \ \forall {w}^{\prime}\in {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{acc}}( w ) [ {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ( {{w}^{\prime}} ) < d_{nec}\to \neg Q( {{w}^{\prime}} ) ] $$b. S presupposes that Q is desirable

c. S asserts that x has/is (at least) d nec of grd in w:

$${\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ( {d_{nec}} ) ( w ) $$

$${\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ( {d_{nec}} ) ( w ) $$d. In case GRD induces a dynamic (action-characterizing) eventuality within the SAG construction, SAG (and thereby S) presupposes the contextual causal sufficiency of a manifestation of d nec-grd for Q:

$${\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{inst}}( {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ) ( {d_{nec}} ) \, \triangleright _{\rm C} \,Q$$

$${\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{inst}}( {\tf="Times-RomanSC (Screen)"\hskip.5mu{grd}}( x ) ) ( {d_{nec}} ) \, \triangleright _{\rm C} \,Q$$

Some comments are in order. The first two conditions in (41) are presuppositional, as is the fourth one. Condition (41a) introduces the existence of a necessary degree, which most accounts of ECs have, in some form or another. Specifically, for all relevant possible worlds, there will be no Q if the necessary degree is not reached. Condition (41b), requiring desirability, is tailored for SAGs only and we will motivate it further. A third presuppositional component is introduced through the condition (41d), which states that dynamic eventualities induced in the SAG will presuppose that a manifestation (or instantiation) based on the gradable property is causally sufficient for Q to hold (in the actual world); see Nadathur (Reference Nadathur2019) for ample discussion in the context of ECs. A simplified way to think about instantiating (gradable) properties is by delimiting them from latent capacities. For instance, it is easy to imagine that a property such as speed (i.e., fast, when expressed with an adjective) is instantiated in a race, but it requires a lot more contextual background to instantiate ‘loud’ in the context of a race.

Let us now consider what the ingredients of (41) mean via an example. In our coffee-drinking example, the scale is temporal, the gradable property is temporal length, the entity supplied contextually is the time available, and Q is the proposition that a cup of coffee is drunk. The latter can be introduced either directly or via the key ‘a cup of coffee’.

For (41a), the existential presupposition is that of a degree of temporal length necessary to drink a cup of coffee (dnec); in all the accessible worlds from the world of evaluation w, there will be no relevant coffee drinking if the necessary degree (i.e. length of time in this case) is not reached. For (41b), S, (1) presupposes that having a cup of coffee is desirable. For (41c), S asserts that the time available (x) is at least as long as the time that is necessary to have a cup of coffee (dnec). (41d) presupposes that a manifestation/instantiation (‘inst’) of making use of the available time causally results in drinking a cup of coffee.

The key difference between the analysis of SAGs and that of ECs is that Nadathur's approach tailored for ECs establishes the instantiation mainly on the basis of the adjective alone (e.g., in simplified terms, in ‘Juno was fast enough to win’ an instantiation is established by Juno running fast to d nec which causally leads to winning). The question then becomes whether length can be acted out in some way. This doesn't seem so, and this makes the correct prediction for ECs, as such examples are not actuality-entailing:

(42) The time available was long enough to have a cup of coffee, but everybody just wanted to have tea, so they did not have coffee.

Unlike in the EC-based paraphrase, however, SAGs actuality entail:

In other respects, we largely follow Nadathur (Reference Nadathur2019) and the literature on causation and implicativity, which our approach builds on. For ECs, the issue of how the realization of the event is cancelled in the imperfective is classically addressed based on technologies reaching back to Bhatt (Reference Bhatt1999). While the same mechanisms could theoretically be applied to SAGs, we will not go into the discussion, because SAGs cannot be conjugated in the imperfective in the first place, as demonstrated in section 2 above.

Finally, while not all of the causation data available for ECs can be transferred to SAGs, there is some evidence that causation is relevant on a descriptive level (beyond the properties of the key). Consider (44):

Discriminating evidence from causal relations can also be observed in SAGs. First, note that while a straightforward causal relationship as in (44) is legitimate, a non-causal one as in (45) – expectedly – is not. More importantly, however, the causal relationship in SAGs needs to target precisely the same scale. In (44) this is the scale of the time available. Just having a(n otherwise legitimate and plausible) causal relationship will not do if the relevant scale is not targeted, as (46) shows:

Cold weather may well cause somebody to drink hot tea. But what is needed, in the SAG, is a causal relation that targets exactly the same scale (in the case of (44), the temporal scale).

We end this subsection by raising a further empirical point regarding the relevance of the additional presupposition we introduced in (41b) above. A manifestation of the property in question cannot always be taken to be desirable in ECs. Consider the following exclamatives. (In a context here stopping a child from playing for too long is relevant, or in any context in which the speaker has had enough of their interlocutor's previous action). In such a context, ECs are licensed (47), but SAGs are not (48):

Presupposing a desirable goal offers a way to explain such types of clashes. For example, in (48), the speaker cannot felicitously utter such a sentence. This follows if a presupposition such as the one we suggested is incorporated. It would be infelicitous to presuppose that the event being performed by the child is desirable and use the utterance to try to stop them from performing it further.

As suggested by Igor Yanovich (p.c.), to test further for the desirability presupposition, we consulted with native speakers of Austrian German on (49) and (50) – both of which feature SAGs paired with normally undesirable outcomes (one with a nominal key, one in the clausal pattern). With regards to (49), speakers report that the student must have been scheming and/or strategizing to fail the exam and, in doing so, spinning an otherwise undesirable outcome for exams into a desirable outcome. Among the possible motivations for doing so was the wish to take the entire class again. When confronted with (50), speakers responded that generally becoming sick is not something desirable but it would be imaginable that there was some form of strategy along the lines of coming down with an infection amidst an epidemic and recovering from it in time before having to take a flight. When pressed about the seriousness of the sickness, speakers concluded that “there must be something going on” or “it makes no sense”.

5. SAGs and approaching the larger picture(s) in change

What did it take for SAGs to develop? What does their development show us about patterns of change in the domains of the source (motion verbs) and result of the change (modality and sufficiency)? In this section we will present observations made during our research in order to strengthen the discussion presented so far, to identify the key conditions that have favoured the rise of the construction, and to offer further thoughts about its significance. The first subsection will offer a brief comparative study, which – despite, but also because of, its negative outcome — strengthens the dating suggested in section 3. Constructions available in German that may have primed speakers in subtle ways and thus promoted the evolution of SAGs will be pointed out in the second subsection. But since we think that the triggering experience must have been stronger than just the autochtonous panorama of particles and reflexives, we will go a step further and investigate the role of language contact in the third subsection. The fourth subsection considers the broader panorama of changes from motion to intensional markers.

5.1 A comparative experiment: linguistic islands

In this subsection, we use language variation to gain supporting evidence for dating purposes. We have dated the beginning of the SAG construction to the 19th century (see section 3). This picture is complicated by the fact that this modal construction has a very low frequency. The fact that SAGs are found primarily in spoken language, and may have been in the past as well, is not entirely problematic, as Austrian and other writers at the time were quite receptive to spoken forms, and to depicting them in their prose. To find supporting evidence for our timeline, we conducted a small comparison with relevant related varieties. What we wanted to see is whether they also posses SAGs.

A relevant comparison can be drawn to the Landler variety of German. This variety constitutes a conservative linguistic island – itself situated within another conservative linguistic island. A current estimate is that approximately 200 elderly speakers speak Landler.Footnote 15 It is spoken in Transylvania; the larger linguistic island by which the Landler variety has historically been encompassed is Transylvanian Saxon. This variety in turn is based on German-speaking settlements dating back over eight centuries and originating mostly in Western German (Mosel river) varieties. These need not concern us much further here, but note that they contain no SAGs (i.e., all SAG structures we tested with native speakers were not only marked but ungrammatical, regardless of context). The main surrounding languages of this island are Hungarian and Romanian, neither of which have SAGs.

The Landler variety emerged far more recently than Transylvanian Saxon, among the successive waves of religious refugees during the Counter-Reformation, beginning in the 1730s and continuing through that century (see Capesius Reference Capesius1990). Most of the banished refugees were originally from Upper Austria and the region around Salzburg (and slightly later and in smaller numbers, also from Carinthia and Styria). While Transylvania was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, it already had a long history of religious freedom and was remote enough from the centre, both in sheer distance and in intervening mountains, for the banished families to be considered less of a threat. Linguistically this ensures its isolated character, as we have no reason to assume that close contact with the Viennese centre might have influenced the colloquial speech of the banished communities. While the Landler variety naturally contains loans from Transylvanian Saxon, Hungarian and Romanian, it is well documented as having preserved its Austro-Bavarian features both phonologically and lexically (see Obernberger Reference AlfredObernberger1964, Capesius Reference Capesius1990, Bottesch Reference Bottesch2006 and references therein.) The speakers settled in a concentrated manner around the area of Sibiu (Hermannstadt in German), essentially in three villages. The important thing for our purposes is that Landler contains neither SAGs nor direct precursors of the construction, so that all SAG constructions available to Austrian speakers today are ungrammatical in this variety. Lexical descriptions are rather sensitive to Austriacisms and typically note them (see Bottesch Reference Bottesch2002, Reference Bottesch2006 on the basis of several types of data collections and elicitation); they do not contain SAGs. We further interviewed one speaker of the variety who decidedly failed to understand the construction and gave it ungrammatical ratings for her own speech and those speakers she was aware of, regardless of context.Footnote 16

(51) *Ein Kaffee geht sich aus. (Landler variety of German.)

a coffee goes itself out

No interpretation available.

Additional factors may have played a role; but the simplest explanation is that the Landler variety does not have SAGs because when it was formed, SAGs did not yet exist in the grammar of its speakers, or at least not in a manner robust enough to be transmitted, in communities where linguistic transmission was, until recent times, key to identity preservation. This may constitute indirect (negative) evidence in support of the 19th century dating suggested in section 3. We now move towards discussing some of the positive clues that might have motivated speakers to come up with the right constructional scaffolding to allow the emergence of SAGs.

5.2 Propitious ground in the landscape of German particle verbs

In order to convey the scalar meanings discussed in the previous sections, SAGs as they are attested in Austrian German require a number of prerequisites at the level of surface form, including the minimal requirement of having the verb gehen, ‘go’, the preverbal particle aus, ‘out’, and the reflexive sich. While this may seem a lot already, note that the verb is extremely common, appearing in many meaning-form pairings with different particles in all varieties of German, and middle constructions – which are based on reflexives – are common in all varieties of German as well. So, the puzzle is genuine – why do we not find the construction in more varieties, or at earlier times? For example, while Austrian German is established as a Bavarian variety, we are not aware of SAGs appearing in the records in autonomous fashion in Federal German Bavarian (despite the fact that some Bavarian speakers nowadays are aware of it as an Austriacism through exposure to the Bavarian variety across the border).Footnote 17

Consider the examples in (52)–(54).

The examples in (52)–(54) are samples of Austrian German at the approximate time SAGs arose, but they are perfectly acceptable in terms of the constructions used in all varieties of German. They involve different degrees of literal meanings of ‘go + particle’, ranging from ‘going out from a particular centre’ to ‘go out’ conveying something like ‘take a particular type of ending’ (which can still be said of marriages, stories, etc.), and ‘go up’ in the sense that a calculation can ‘work out’. In particular, the latter type of example could, for instance, be a good candidate for a close relative of SAGs, as there is a sense of a match between two states of affairs (the way a calculation should be conducted and the way it is – viz. if the two fit one another, then the calculation is properly conducted).

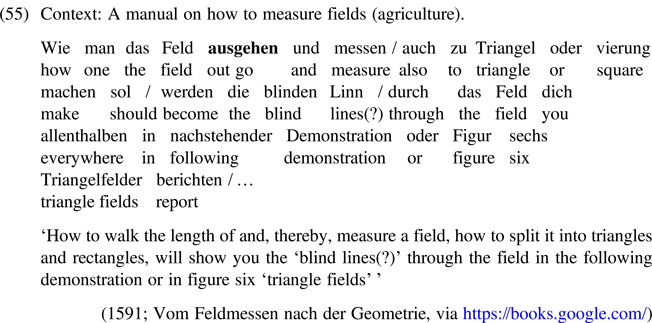

The example in (55) is another interesting candidate for a relative of SAGs.

Example (55) features the meaning of ‘going out’ in the sense of ‘measuring out’ a field (note the co-occurring messen, ‘measure’). This meaning has been standardly available in High German, and is attested in the Grimm Brothers’ classical dictionary of the language. All it would take, then, is a middle construction realized through a reflexive, which is attested with many verbs in German. While we find this scenario theoretically attractive, it has two major drawbacks. The first one is shared with the constructions we introduced above in (52)–(54): it consists in the fact that all these constructions have existed in standard non-Austrian varieties of German as well. The second disadvantage has to do with the following: if the construction were the origin of SAGs, then following all standard accounts of language change, we would expect it to appear particularly frequently in the variety in which the putative descendant (i.e., SAG) is later attested, at the time preceding the rise of SAG constructions. To verify this, we conducted multiple collocational searches in the Austrian corpus ANNO (including other objects that, according to the Grimm dictionary, could co-occur with ausgehen having this meaning), but we found virtually no bona-fide hits. In fact, unlike the other constructions discussed, (55) does not stem from the Austrian German ANNO source, but rather from a book published in Leipzig. We then see a mismatch in terms of the evidence available to us and the possibility of having the close meaning of measuring out an object as a likely scenario. Our interim summary therefore is as follows: while apparently related constructions may have offered propitious ground for accommodating SAGs in Austrian German, none of them has both the necessary meaning components and the power of the attested evidence to be classified as ‘the’ legitimate predecessor.

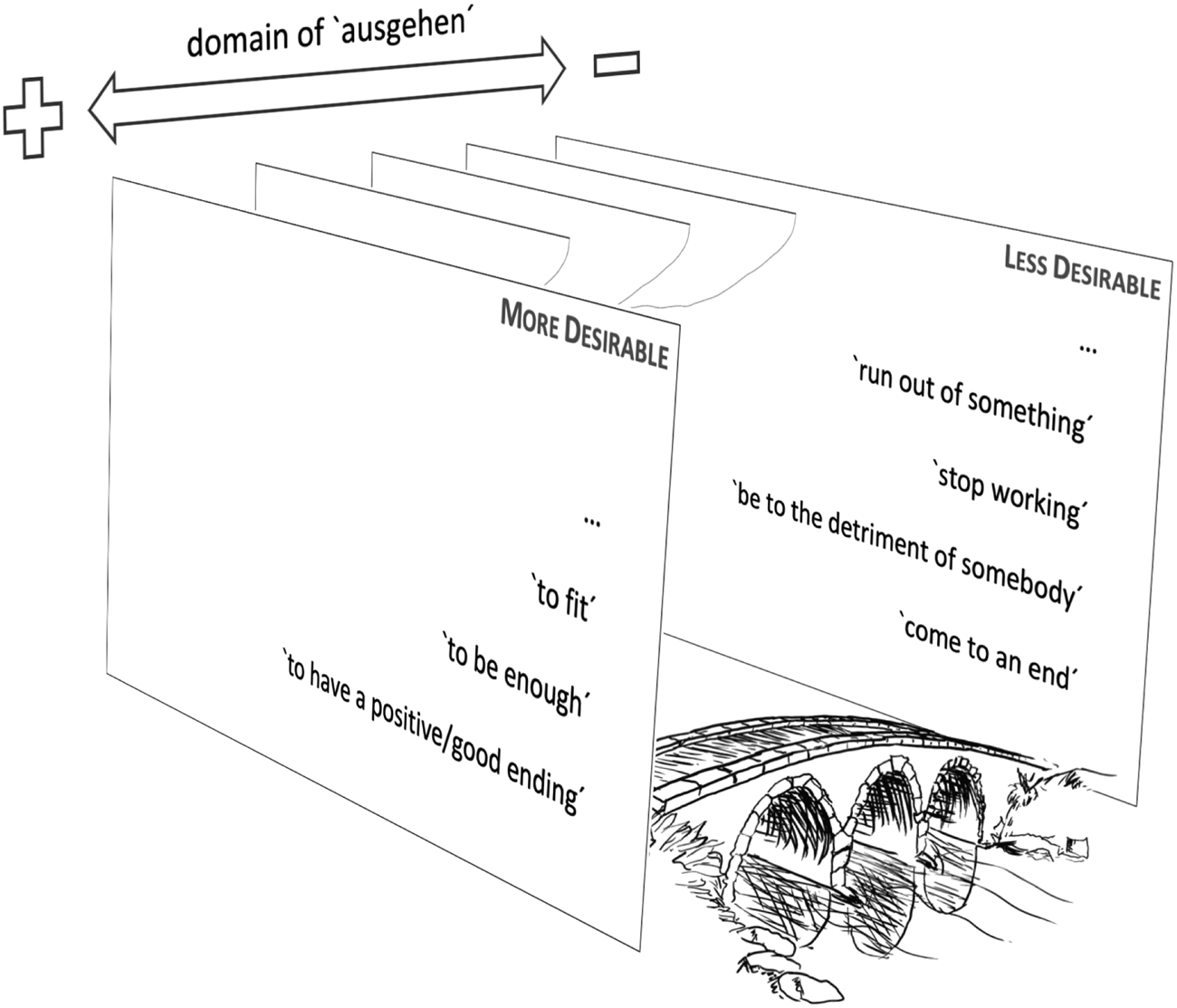

Before moving on to a relevant contact situation possible in Austrian German in the next subsection, we will end this section with a slightly more associative view, which we hope may help the reader to grasp some of the main developments and key meanings available en route to SAGs. Consider Figure 5.

Figure 5: Conceptualization diachronic change, domain of aus + gehen

One intuitive feature that sets genuine SAGs apart from many other constructions based on ausgehen ‘go out’ such as ‘run out of something’, ‘be finished’, etc. is its positive – more specifically: desirable – character; we incorporated this in section 4 as a presupposition. As a usage-based tendency, certain predicates we observe in the data appear to be associated more easily with contextually desirable outcomes than others. Some of the major players among these predicates are schematically given in Figure 5. There are, of course, more apparently (un)desirable particle constructions, however. And there are connections between the two domains. For instance, having an ending might appear as negative, but having a positive ending (gut ausgehen) is highly idiomatic and clearly positive. In fact, the frequency of gut ausgehen, ‘go out well’ rises in the period during which SAGs develop, as Figure 6 shows.

Figure 6: frequencies: gut ausgehen (%); detailed numbers in table 8

It is possible that such bridges towards positive completions have brought a ‘desirable’ character into the picture.Footnote 18 Similar facts can be observed with the cognate particle out in English: work out, pan out, play out etc, where the result state is usually contextualized as desirable.

5.3 Contact

We now turn to a different perspective on language change, i.e. we move from internal towards external factors and specifically to the issue of language contact. A quick socio-historical background reminder is that the Austro-Hungarian empire (the relevant entity when SAGs first appeared) was a multi-national state. Austrian German up to this day contains a large heritage in its lexicon (but partially also beyond; see Hofmannová Reference Hofmannová2007 and references) of several languages earlier spoken within the same cultural area. While we could not find a relevant construction in Hungarian, we will sketch the potential role of Slavic, and in particular Czech, in the rise of SAGs.

In doing so, we essentially follow a hint from Glettler (Reference Glettler1985), a rather comprehensive study to illustrate the role played by the large Czech-speaking community in particular in 19th century Viennese society from a historical point of view. The study yields a large background in cultural and sociolinguistic terms and it also addresses some putative direct linguistic influences from Czech. Glettler (Reference Glettler1985: 105) in fact claims that SAGs are a loan construction from Czech in the negative past tense. Unfortunately, while Glettler offers examples and citations of attested examples to substantiate many of her claims in other borrowing contexts, she mentions the relevant lexical items, but does not offer either sources or any full Czech (or Austrian) SAG sentence (much less context) to substantiate her interesting claim. We want to point out, however, that the possibility of having an implicative possibility construction based on a verb of movement imported to some extent as a calque from Slavic seems to us very likely in the sociolinguistic context. German and Slavic varieties certainly had a history of contact in many other contexts, too, but as Glettler (Reference Glettler1985) points out, it is crucial that many expressions from Czech make it to fashionable and respectable Viennese items in all registers. Newerkla (Reference Newerkla, Newerkla and Poljakov2013) claims a particularly intensive contact situation starting in the last third of the 19th century, noting, for instance, that 25,186 citizens were registered in Vienna in 1880 as having a Czech/Slowak/Bohemian linguistic background. While Newerkla's views on languge contact are refined, when it comes to SAGs, we could find no systematic discussion of actual attestations.Footnote 19

While we think that an analysis (or even a description) of related Slavic constructions might deserve a serious study in its own right, we will simply point out some of the main coordinates relevant for SAGs.

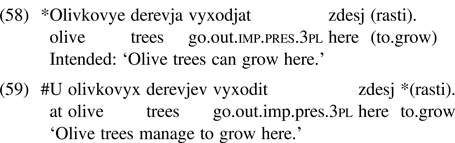

First, notice that verbs based on ‘go out’ in Slavic have developed a modalizing semantics also beyond Czech, as the following Russian examples (Igor Yanovich, p.c.) illustrate:

While the examples mimic the SAG examples from Austrian, they do not, as Yanovich points out, require a notion of scale. Furthermore, the example about the possibility of growing olive trees – which is not felicitous in Austrian German – is also not acceptable in Russian, as the two following examples illustrate.

Here again we follow Igor Yanovich (p.c.) and assume that the reason for the different status of this example is not identical to the reason we suggested for the infelicity in the Austrian German counterpart (lack of an obvious scale). Rather, this seems to be related to the agreement pattern available in Russian (in the first version, the nominative argument of the modal vyxoditj is the infinitive clause, while the second version is strange pragmatically, because it more or less anthropomorphizes the trees). We conclude that the Russian construction has slightly distinct properties, and leave it to future research to consider the points of micro-variation in such modalizing constructions in Slavic languages.

We finally turn to Czech, following Glettler's (Reference Glettler1985) hint. Czech has several related modal constructions. Mojmír Dočekal (p.c.) points out that one construction consists of the subjunctive of the motion verb ‘go’. While this is a very interesting path to follow in its own right, we will not focus on it here because the subjunctive free morpheme by essentially comes down to ‘would’ in English. Therefore, so does the modalization itself (as expected). What we wanted to know however, is how constructions based on the past negative motion verb nevyšlo, as pointed out by Glettler (Reference Glettler1985) (and reverberated, unfortunately also without examples, by Hofmannová Reference Hofmannová2007 and others) behaved. Dočekal (p.c.) points out the following paradigm of the relevant examples in this case:

Notice that translations can be problematic and obscuring here too. While nevyšlo has been translated by the negative past of ‘work out’, vyšlo could be translated by ‘went out’, which shows that we are indeed dealing with the relevant motion verb. A further point, however (in this case, one of divergence), is that all the examples are felicitous in the first place, in particular the example (62). However, an example like (62) is not felicitous for its Modern Austrian counterpart (i.e., SAG), as we have shown. The construction then has some strong similarities with the Austrian SAG, but it is not identical. The latter point does not rule out, of course, identity at an earlier historical time. On the contrary, given that the pre-SAG constructions allowed more general compatibility and fitness readings, it is quite likely that they may have been influenced by contact.Footnote 20

5.4 SAGs in the larger panorama of ‘go’ constructions

In this subsection, we point out the significance of two points from our findings in the landscape of grammaticalizing ‘go’ constructions, viz. emerging presuppositions, and the role of the compatibility reading of early (pre-)SAGs found in our investigation. We show that this pattern is in fact more general than what has been observed so far. We thus hope to open the door not only to further detailed investigations of SAGs themselves, but also more generally to a side of ‘go’ constructions that has received less attention.

The grammaticalization literature has noted the patterns of change (see Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994, Narrog Reference Narrog2012) schematically represented in Figure 7. Based on a case-study conducted on Hebrew, Rubinstein and Tzuberi (Reference Rubinstein and Tzuberi2018) refine the picture by suggesting that it is also possible to get a vertical developmental path in Figure 7, directly from movement to desires as well.

Figure 7: Paths of Motion Verbs (Originally after Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994: 240, reproduced in Narrog Reference Narrog2012: 83 and Rubinstein and Tzuberi Reference Rubinstein and Tzuberi2018: 2)

Our plot is not directly comparable in its details to these paths, but we present the following two observations in connection with ‘go’. First, desirability may be introduced as a presupposition and not only as the at-issue meaning, as it is clearly not the asserted meaning in SAGs. We are not aware of many studies on emerging presuppositions, and believe this deserves more attention in future research (see Schwenter and Waltereit Reference Schwenter, Waltereit, Davidse, Vandelanotte and Cuyckens2010, Beck and Gergel Reference Beck and Gergel2015, Gergel et al. Reference Gergel, Kopf-Giammanco and Masloh2017).

The second and broader point is the following. In addition to making excellent futurate markers (not only in English; see Eckardt Reference Eckardt2006), but in a broad range of languages, as we know from the typological literature (see Ultan Reference Ultan and Greenberg1978, Giger Reference Giger, Kosta and Weiss2008, among many others), ‘go’ constructions can also give rise to compatibility and sufficiency constructions. This is also interesting from the perspective that the emphasis on previous grammaticalization research has been from ‘go’ (or movement), to necessity operators Bourdin (Reference Bourdin, Devos and van der Wal2014). The noted development in the grammaticalization literature would nicely incorporate futurates, as these are usually viewed as necessity operators; Copley (Reference Copley2009) and certainly also sufficiency constructions from a general perspective. However, it appears too simplistic to state that sufficiency just corresponds to a universal operator in the process of semantic change and that this should be the same type of development (i.e., of a motion verb towards a universal). Recall that the pre-SAG meanings seem more like possibility than necessity meanings.

Thus the completive particle ‘out’ discussed earlier is not the only source that might have primed speakers towards easily accepting and using a construction, originally with a sense of compatibility, as the diachronic evidence from section 3 indicates. The verb gehen, ‘go’, itself also has a clear potential towards developing markers of compatibility, success, suitability etc. Constructions like the following are common in varieties of German.

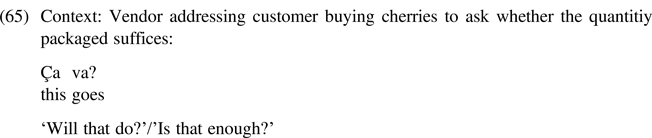

The case of French also shows this, where Ça va can mean, among many other things, ‘This works out’, ‘This is fine’, ‘I agree’.Footnote 21 Interestingly, one available meaning is of sufficiency, used in a type of example that is disallowed in SAGs.

Having established empirically the relevance of compatibility readings in the contexts of ‘go’ constructions in our specific SAG plot, diachronically, as well as more generally, two more detailed questions arise. First, why is it so easy, in some cases, for compatibility and sufficiency to be conflated? Part of the answer is that, in numerous cases, the sufficiency reading entails the compatibility reading. If there is enough time to have a cup of coffee, then it is possible to have a cup of coffee. In this case, the reversed entailment also obtains. Furthermore, if the specific contexts in which the two readings are roughly co-extensive are numerous, then it is possible for the construction that was recruited (i.e., SAG) to take over the sufficiency reading. Why then – and this is the second question – does this kind of specialization via grammaticalization only happen in some cases (notably SAGs), but not others (say, gehen by itself or the French verb aller)? Part of the answer may lie in the easy ability of the construction to be recognized as a form-meaning correspondency of its own (recall its quirks of involving a reflexive, a particle, and in propositional contexts an expletive, etc.). Other expressions in Austrian German in the 19th century that could signal compatibility in discourse situations are passt, ‘fits’ and das geht, ‘this goes’ (also in conjunction with further discourse particles such as schon, unfortunately untranslatable, but see Zimmermann (Reference Zimmermann2018) for an analysis). In fact, both of them were on the rise, as Figures 8 and 9 indicate.Footnote 22

Figure 8: frequencies: passt! (%); detailed numbers in Table 6

Figure 9: frequencies: ja das geht schon (%); detailed numbers in Table 6

There was, then, no possible pressure for SAGs to maintain the more general function of compatibility/suitability, as the two alternatives (among others) were increasingly popular.

To summarize: in the course of this article we have offered a description of Austrian SAGs, the core of which we have suggested can be analyzed in line with enough constructions. We have provided initial diachronic attestations, as well, but had to come to a slightly unusual conclusion. Given that the language-internal ingredients have been widely available in all varieties of German (without ever giving rise to the construction), together with the relative singularity of the construction in Austrian German, we adopted a contact-based approach, following a hint by Glettler (Reference Glettler1985) and others who mention the construction in passing. It has to be emphasized that the sociolinguistic situation was propitious for Czech constructions to be imported to Austrian (and in particular Viennese) German in the 19th century and this would match the late attestations we have found (keeping in mind the possible delay in the attestations due to the oral character of the construction). At the same time, what we called the core of SAGs (i.e., their sufficiency semantics) is not visible to us in their Czech counterparts as such. Several possibilities become theoretically available (imperfect transfer in contact, changes in either language since the borrowing event, etc.). But given that a conspicuous meaning in the pre-SAGs we found is one of appropriateness or compatibility, it is possible that such a meaning was first borrowed. Our hope is that the window is open widely enough for further diachronic research to contribute to the landscape of modalizing ‘go’ constructions.

Appendix A: ANNO-Corpus

General Description

The ANNO corpus (AustriaN Newspapers Online) is a historical newspaper corpus published and continuously expanded by the Austrian National Library. According to the ANNO website, the corpus covers the periods 1689–1948. We focused on the material which was available as txt-files, starting in 1700. For the last phase of our corpus study on ANNO, there were 1288 titles available (including double listings for rebrandings, launches of newspapers, etc.). There was a total of about 1.312 million newspaper issues online, resulting in a word count of about 21.6 billion. While the ANNO corpus is quite extensive, it is also diachronically imbalanced. Table 1 shows the word counts per decade across the entire corpus (as far as available in txt format). The median year lies between 1900 and 1910.

Table 1: ANNO, diachronic structure; Jan. 20, 2019

Web-based search in ANNO

In an initial effort to skim for SAGs in the ANNO corpus, we were left to rely on the rather weak web-based search tools the ANNO website comes with. There is no additional annotation layer that could be used for a more refined search. Any search would ignore sentential boundaries and a search for <geht sich aus> would include any text that contains geht, sich, and aus.

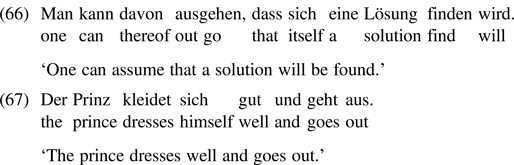

Due to this weakness, every list of hits had to be manually reviewed. Occurrences of SAG had to be extracted from the pool of non-relevant uses of sich, aus, ausgehen, and gehen; see, for instance, (66) and (67).

We pursued two major strategies in finding SAGs in the ANNO Corpus website. The first was an initial, ‘targeted’ search for <“geht sich aus”> (with phrase search tool “ ”) which returned 31 search hits, three of which were SAGs. Consecutive searches also returned hits that could be sorted manually with relative ease. Based on <“ging sich aus”>, <“ging sich nicht aus”>, <“ist sich nicht ausgegangen”>, <“wird sich ausgehen”>, and <“gingen sich aus”> another 7 SAGs were found. In total, we ended up with ten SAGs with such targeted searches.

The second strategy was a wider search. A distance parameter was added to four search terms (“~4”, i.e., distance of four intervening words and in arbitrary succession). For each of these four diachronically ordered searches, we manually went through the first 1,000 hits (among a total of 4,000), to identify SAGs. The search hits that were reviewed manually contained no SAGs at all, but only other, non-relevant uses of the above-mentioned building blocks. See details on the corpus search below, in Table 2.

Table 2: Searches and search hits in ANNO corpus; number of hits from Feb. 5th, 2018

Offline searches in ANNO corpus

General strategy

For our in-depth search of the corpus, we applied the following strategy. We downloaded the txt files in the ANNO corpus. We then ran a number of Python scripts skimming for SAGs based on regular expressions (regexes). Those scripts returned high volumes of hits (predominantly false hits) which we manually skimmed for positive hits.

Handling of OCR errors

Since the ANNO corpus files are based on digitized newspapers, there is a high density of optical character recognition (OCR) errors. One of first steps was creating a list of common OCR errors for sich, aus, forms of gehen – the buildings blocks of SAG – and nicht (a German negative). This was done by human visual detection of those items in the scanned pdf files of the newspapers and looking up their OCR-correspondences in the parallel txt files. The list of OCR-correspondences informed some of the regular expressions searches on the entire corpus (see below). This tracking of OCR errors was not done for the web-based searches of ANNO described above.

Regular Expressions

The following is a breakdown of how we proceeded in making sure we caught as many SAGs as possible and at the same time limited the number of false hits. As mentioned above, our search for SAGs included sich, aus, and forms of gehen (and all their plausible dialectal spelling variants). Additionally we included negation (nicht, nie, nimmer, etc.). We focus on the most recent and most effective mode of searching; the most important details in the regexes below are the following. We relied on periods, exclamation points, question marks, colons, and semicolons as sentence/clausal boundaries. We excluded comma-symbols appearing across the S, A, G, (and N) building blocks of SAG in order to ensure that (in the list of hits) all three items occur in the same clause and, thus, increase the probability of excluding false hits. As a consequence, potential positive hits with embedded clauses or enumerations occurring between SAGs (which are grammatical in present-day Austrian German – and marked with commas) were excluded. The only characters allowed between the building blocks of SAGs are captured in (69). We allowed a maximum of 50 characters between each building block.

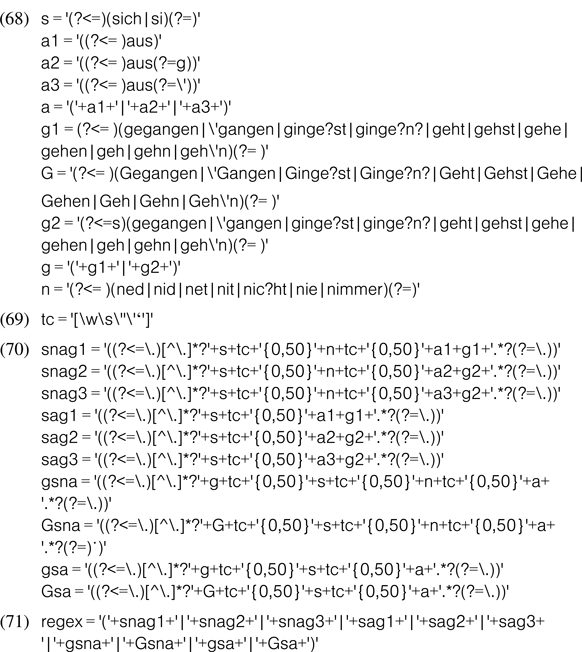

For ease of handling regexes based on the three items making up SAGs (four when counting negation), we had a multiple-level strategy for compiling our regexes. The following are our four items formulated as regexes (in Python) accounting for spelling variants – all stored as variables (S, A, G, N) to be used in another regex:

With the above regex (68)–(71), we obtained a list of 3348 hits. We have so far manually reviewed 2042 hits, which yielded 119 hits of (pre-)SAGs. This number can be reasonably projected to the full length of 3348 since – during the run of the regex-script – the filenames were chosen at random and the 2042 hits were checked top-down. The resulting projection on the above assumptions would bring us to 195 SAGs.

In addition to the above strategy, we did targeted searches accounting for OCR-errors. The following serve as examples (in the form of regexes) as to what potential errors we tried to account for:

The regex variables in (72)–(75) were plugged into larger regexes (similar to the procedure for (68)–(71)). We ran multiple scripts, and variations regarding the degree of accounting for OCR errors, distances and excluding potential noise (e.g., the German preposition auf, albeit being a probable candidate for OCR errors based on the ‘descending s’). With these additional probing strategies, we were able to increase the number of unambiguously identified (pre-)SAGs to 168. The frequencies and numbers, per decade, appear in Table (3).

Table 3: SAG; frequencies and number of hits

Table 4 shows the geographic distribution of the papers in the ANNO corpus whose main place of publication is within present-day Austria.

Table 4: ANNO, geographic structure, by main place of publication; by Jan. 20, 2019

Appendix B: The sufficiency modal construction

Consider (76), analyzed in von Fintel and Iatridou (Reference von Fintel and Iatridou2007):

(76) To get good cheese, you only have to go to the North End!

As von Fintel and Iatridou (Reference von Fintel and Iatridou2007: 446) put it: the sentence “seems to say that going to the North End is enough or sufficient to get good cheese, so we will call the construction in [(76)] the sufficiency modal construction (SMC).”

We may observe that, compared to classical ECs (i.e., those based on words such as enough in English, genug in German, or assez in French), there is a feature that SMCs and SAGs appear to share, in counterdistinction from ECs. The latter have an acknowledged intensional dual in the too constructions in English (and similarly in other languages). For instance, if Sally is too young to drive, then Sally is, equivalently, not old enough to drive. According to von Fintel and Iatridou, only the universal is a licit modal in SMCs. We observe that SAGs indeed do not have a precise dual.

There are, however, some important differences, which set the SMC and SAGs apart, so that the two analyses must also be distinct. First, as von Fintel and Iatridou (Reference von Fintel and Iatridou2007) point out, the SMC is cross-linguistically stable, with variation ranging largely alongside two types of patterns. As far as we have been able to determine, SAG does not in any way have a universalist tendency, even within German varieties, although certain relatives and possible precursor constructions can be identified.

Second, the SMC involves an only operator, which can be overt or covert, depending on the language. English (and similarly German) has the overt version (see (76); while French has a covert version and a different way of encoding the construction). This becomes crucial in the analysis of SMCs which is developed in terms of scopal properties of the operator. SAGs, however, do not require such an operator in either fashion. We take it to be analytic parsimony, therefore, that a first description should not appeal to it in this case (no matter how convincing the case for only in SMCs appears to be).

A third point on which SMCs and SAGs part ways (not investigated in von Fintel and Iatridou's contribution), has to do with actuality entailments. We note here that SMCs do not show implicative behaviour with respect to their complement:

(77) (To get good cheese,) you only had to go to the North End, but you took the wrong bus (and miserably failed)!

Sentences such as (77) show retraction of the implication and hence do not display the relevant actualistic behaviour. This is in contrast with SAGs.Footnote 23

Appendix C: Acceptability ratings and readings obtained

We designed a questionnaire and recruited Austrian German speaker subjects via social media platforms. The questionnaire consisted of ten sentences (see Table 5). For each of the sentences presented, the subjects were asked to (i) rate its acceptability on a scale ranging from 0 (“not good”/”sounds wrong”) to 10 (“good”/”sounds right”) and (ii) provide a paraphrase giving their reading/interpretation of the sentence. The experiment yielded 84 × 10 responses (the judgements of 84 speakers). We invite the reader to consult Table 5 before we move on to a discussion of some of the results.

Table 5: Sentences and acceptability ratings

A first point is that sentence number 1 obtained the overall highest rating, at 9.14. No other reading than the temporal one was detected in the paraphrases offered for this sentence. Of course, the noun Termin (‘appointment’) in the sentence makes a temporal scale highly salient. The second highest overall rating, at 8.89, was received by another sentence which made a scale explicitly salient (sentence number 9, with a monetary scale regarding the budget available for holidays).

Conversely, the lowest average rating was received by the second sentence (‘‘Es geht sich aus, dass in meinem Garten Olivenbäume wachsen.”) with a score of 3.96 out of 10. The sentence is then clearly odd. We suspect the major reason is that it does not make any type of scale salient (even if circumstances such as climate, soil, etc. could easily come to mind). Interestingly, however, when responding to the second task (i.e., assigning a meaning to the sentence), the majority of speakers interpreted it as having a degree-based reading nonetheless. Thus, the most frequent reading reported by subjects was a spatial reading (‘enough space in the yard’) with 57 such responses, out of which 38 were exclusively spatial. A possible interpretation, then, is that the sentence produces a clash between what would be expected for a SAG and what is directly provided by the extension of the predicate and its arguments. Having recognized this, the preferred interpretation is still one in which a scale would be interpreted in the context.