The last two decades have seen the opening of several new paths in eighteenth-century musicology, and Robert O. Gjerdingen has opened one of these: schema theory. Schemata are ‘stock musical phrases employed in conventional sequences’Footnote 1 that function as harmonic, melodic and rhythmic frameworks for musical passages. Evidence of such schematic thinking has emerged through related studies on partimento and solfeggio.Footnote 2 Solfeggio practice of the time manifests a schematic way of thinking about music, being mostly based on simple hexachordal patterns which, as studies progressed, could be embellished in different ways. Vasili Byros has addressed the ‘archaeology’ of hearing through reception history, and offered strong evidence that eighteenth-century ears did hear schemata.Footnote 3 Interweaving corpus studies on music of the long eighteenth century (1720–1840), contemporary music criticism and reception history, as well as didactic documents from that era, Byros sheds new light on the ways in which schemata were perceived at the time. A recent contribution by Gilad Rabinovitch uses a live improvisation in the style of Mozart by Robert Levin to demonstrate the importance of conventional schemata for historical improvisation.Footnote 4

Yet discovering traces of schematic thinking still represents a difficult task. Gjerdingen deduces schemata through painstaking analyses of countless pieces from different parts of the century; partimento and solfeggio studies, which mostly examine didactic material, infer that schemata might have considerably influenced both composers’ and interpreters’ minds. My essay aims to contribute to and broaden this field of research by considering a full-scale operatic score through the lens of solfeggio. Not only did composers have solfeggio patterns in mind when creating music, but singers also read scores schematically. I will consider an obscure Neapolitan operatic manuscript: Francesco Gasparini's La fede tradita e vendicata (Naples, Teatro San Bartolomeo, 1707), whose comic scenes display an apparently odd use of beamings and slurs which may refer to solfeggio practice. Giuseppe Vignola (born 1662–died 1712)Footnote 5 composed the music for these comic scenes, which feature the protagonists Lesbina and Milo. He played an important role in writing such scenes for insertions in other composers’ operas between 1706 and 1712 in Naples. The libretto validates this information, for it names Vignola as having adapted the pre-existing opera according to Neapolitan taste.Footnote 6 Taking account of arias composed for early eighteenth-century Neapolitan comic singers, I will show how some graphic elements of their manuscripts could suggest a distinction between core solfeggio syllables and embellishments, instead of being classified as mere copying errors, as they might appear to be at a glance. These graphic elements were targeted at particular kinds of singers, the comic ones, and not by chance: their musicianship was less refined than that of the great castratos, and thus they needed graphical ‘help’ in the scores they had to learn. For instance, in 1781 Bolognese man of letters and theatre historian Francesco Bartoli compiled a collection of biographies of some performers of commedia dell'arte, including a certain Rosa Costa:

ROSA COSTA. Recitava nella comica compagnia del teatro di S. Luca in Venezia . . . Oltre il recitare nelle commedie, possedeva ancora l'abilità di cantare.Footnote 7

ROSA COSTA. She acted in the comic company of S. Luca in Venice . . . Besides acting in comedies, she was also able to sing.

Her singing abilities allowed her to play roles in operatic intermezzos in northern Italy.Footnote 8 This suggests that the professional lives of actor-singers involved in the performance of comic intermezzos were more closely linked to the commedia dell'arte tradition than to music apprenticeships in Neapolitan conservatories.Footnote 9 It follows that the pieces they sang, at least at the very beginning of the eighteenth century, were so simple that it might have been easier to conceive them as a series of solfeggio patterns, rather than as fixed compositions to be realized exactly in accordance with the anachronistic concept of Werktreue.

In addition, I argue that music philologists should be more careful in dealing with graphic elements such as beaming and slurs, which might appear incoherent. As the evidence will suggest, they could be bearers of hidden solfeggio meanings which are, for us, difficult to decipher. This essay will expand on three case studies from the manuscript. This solfeggio-related notation is, however, present in other parts of these comic scenes as well as in other manuscripts: I will limit myself to citing other examples that suggest the presence of such notation.

SOLFEGGIO

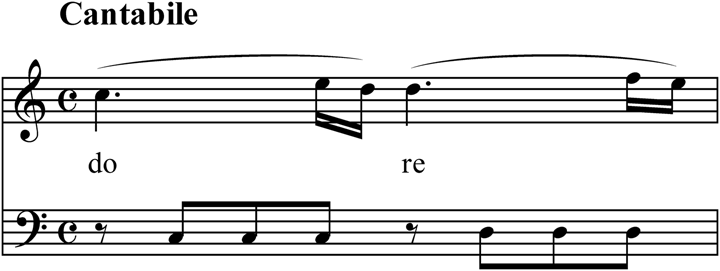

Before starting work on partimento, students spent at least three years practising solfeggio. Studies of early eighteenth-century solfeggio, a pedagogical method through which generations of musicians learned music, are only of recent vintage, and have been carried out by Nicholas Baragwanath.Footnote 10 Neapolitan music students learned solfeggio as if it were a language: not through theoretical study, but through exercise and continuous exposure. As Baragwanath maintains, ‘maestros taught their students to acquire skills in solfeggio intuitively . . . This proved easier and more effective than learning the hard way, by studying rules from a textbook’.Footnote 11 The students’ ABCs were the six Guidonian syllable-notes, which they integrated with aural experience. Soon they started to convert these notions into equivalents of speech acts by singing them (sung solfeggio). Initially, they sang intervals arranged into scales and leaps (musical ‘words’). As the studies progressed, patterns of more than one note became standard, as if they were syntactic units, or frameworks for phrase structures, amongst which were the Do Re Mi as well as descending hexachords, scales and other patterns. At this point, it is worth specifying that solfeggio syllabic patterns are similar, but not identical, to Gjerdingen's schemata. In the case of the Do Re Mi, of course, the solfeggio pattern and the schema would be very close; this does not apply, however, to the descending hexachord, a common solfeggio pattern on which, besides the Do Re Mi, I will focus. These frameworks were then subjected to various kinds of division. After students memorized thousands of different vocal renditions of the same pattern, they built an inner knowledge of musical ‘words’ and ‘phrases’ which could be elaborated into ‘sentences’. ‘Speaking’ eighteenth-century music was, therefore, the ability to transform basic syllables and stock phrases into a fully fledged vocabulary of sounds to combine together.Footnote 12

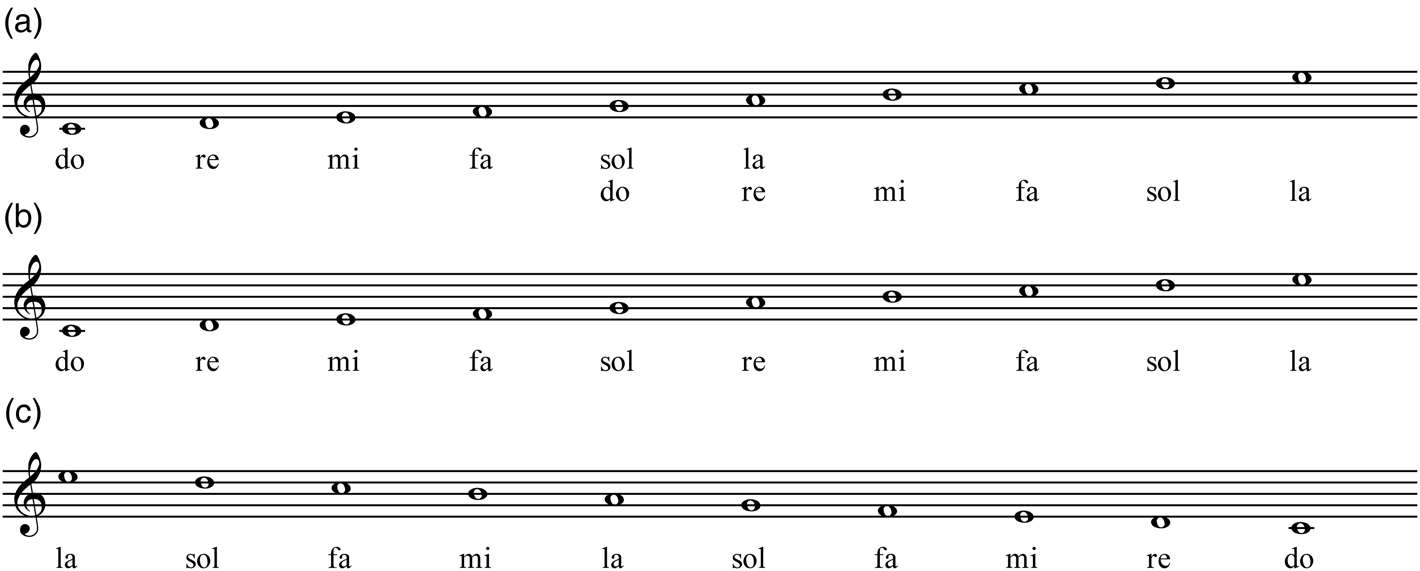

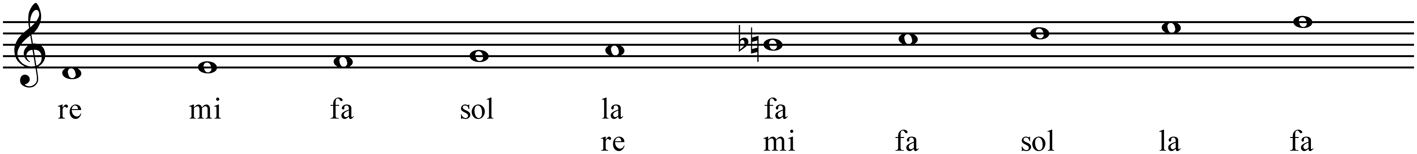

For a better understanding, I believe it is worthwhile explaining how these students learned to sing scales. In a system covering a tenth, they combined two Guidonian hexachords in the manner shown by Example 1a. If the scale were to be sung ascending, they used the pattern in Example 1b; if it were to be sung descending, they used Example 1c. The Do Re Mi pattern mentioned above is akin to what Gjerdingen referred to as ‘Do Re Mi’ because of these very syllables. Gjerdingen's Do Re Mi, in other words, stands for a three-note ascending solfeggio pattern, each one at a distance of a whole tone, like the first three syllables of Example 1a. The peculiarity of this system is that every semitone was to be sung as mi–fa (or fa–mi, if descending). For this reason, when the hexachordal scale was to be rendered in a minor mode, they added a ‘fa’ syllable over the last note. This process is explained in Example 2: the equivalent of a minor mode, for them, was a scale beginning on the syllable ‘re’ (Re mode).

Example 1 Solfeggio scales

Example 2 Solfeggio scales, Re mode

As the reader can see, some notes could have more than one name. Neapolitan students were able to discern, by following the melodic contour, which syllable to choose. For example, if a melody's range covered only the first six notes of the ten-note scale of Example 1a (major mode), they would have tried to sing it using only the first hexachord.

The melodies we see today can thus be ‘reduced’ to solmized notes: a painstaking operation for us, but second nature for eighteenth-century students. They did not see pages covered with bravura passages, but solmized syllables to which a particular type of embellishment was applied. And these types of embellishments were learned through practice, experience and variations on the same simple patterns. Reconstructing the standard patterns, for us, is not an easy task. I focus on two very basic ones: the already mentioned Do Re Mi, and the descending la-do hexachord (or fa–re, if in minor mode).

Two basic rules, in the students’ minds, governed the ‘reduction’ process: the Amen-rule and the Appoggiatura-rule. According to the first, a series of notes connecting a two-note interval is dependent on the first syllable; according to the second, on the last syllable. Figure 1 schematizes these rules for the sake of clarity.Footnote 13

Figure 1 Amen-rule, from Lorenzo Penna, Li primi albori musicali (Bologna, 1679), 42, and Appoggiatura-rule, from Adriano Banchieri, La Banchierina: overo, Cartella picciola del canto figurato (Venice: Alessandro Vincenti, 1623), 24

Traits of vocalizations, the graphic signs that have been discovered by Baragwanath,Footnote 14 helped early-stage solfeggio students to distinguish between the Amen-and Appoggiatura-rules. They consist of almost straight pen lines to be found in pedagogical primary sources for solfeggio lessons. Embracing more than one note, they told the student not to change the solmization syllable and to consider all the notes as embellishments, following (like an Amen) or preceding (like an Appoggiatura) the core solmized syllable. Figure 2 shows an example, cited by Baragwanath, of one solfeggio lesson by Saverio Valente, a late eighteenth-century maestro in Naples.

Figure 2 Saverio Valente, ‘Teoria musicale, o sieno principj della spiegazione di tutto ciò che potrà accadere nell'imparare la musica sì vocale, che strumentale’. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica Giuseppe Verdi, Milan (I-Mc), Noseda Q.13.19, fol. 2v, cited in Nicholas Baragwanath, The Solfeggio Tradition: A Forgotten Art of Melody in the Long Eighteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 135

The dashed, curved slurs indicate breathing; the other, less curved ones are traits of vocalization. In bar 1, the latter slur indicates to the student that he or she should continue to pronounce the syllable ‘do’ while singing a C♯, conceived as an ornamental chromatic passing note from that same ‘do’, and not as a single independent note. The same could be said for bar 3. I will build on this fundamental concept of ‘trait’, exploring other possible types of traits and beamings.

The philological norms that govern major eighteenth-century critical editions are very clear on some aspects.Footnote 15 A united beaming indicates syllable prolongation, whereas a separated beaming indicates a separation of syllables. Sometimes slurs that indicate a prolongation might be present. As will be pointed out below, they might refer to solfeggio practice as well.

CASE STUDIES

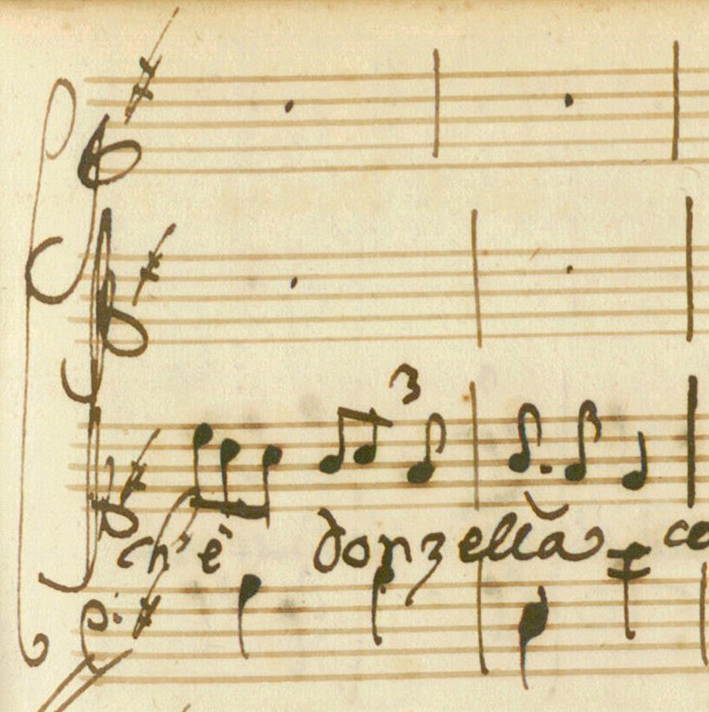

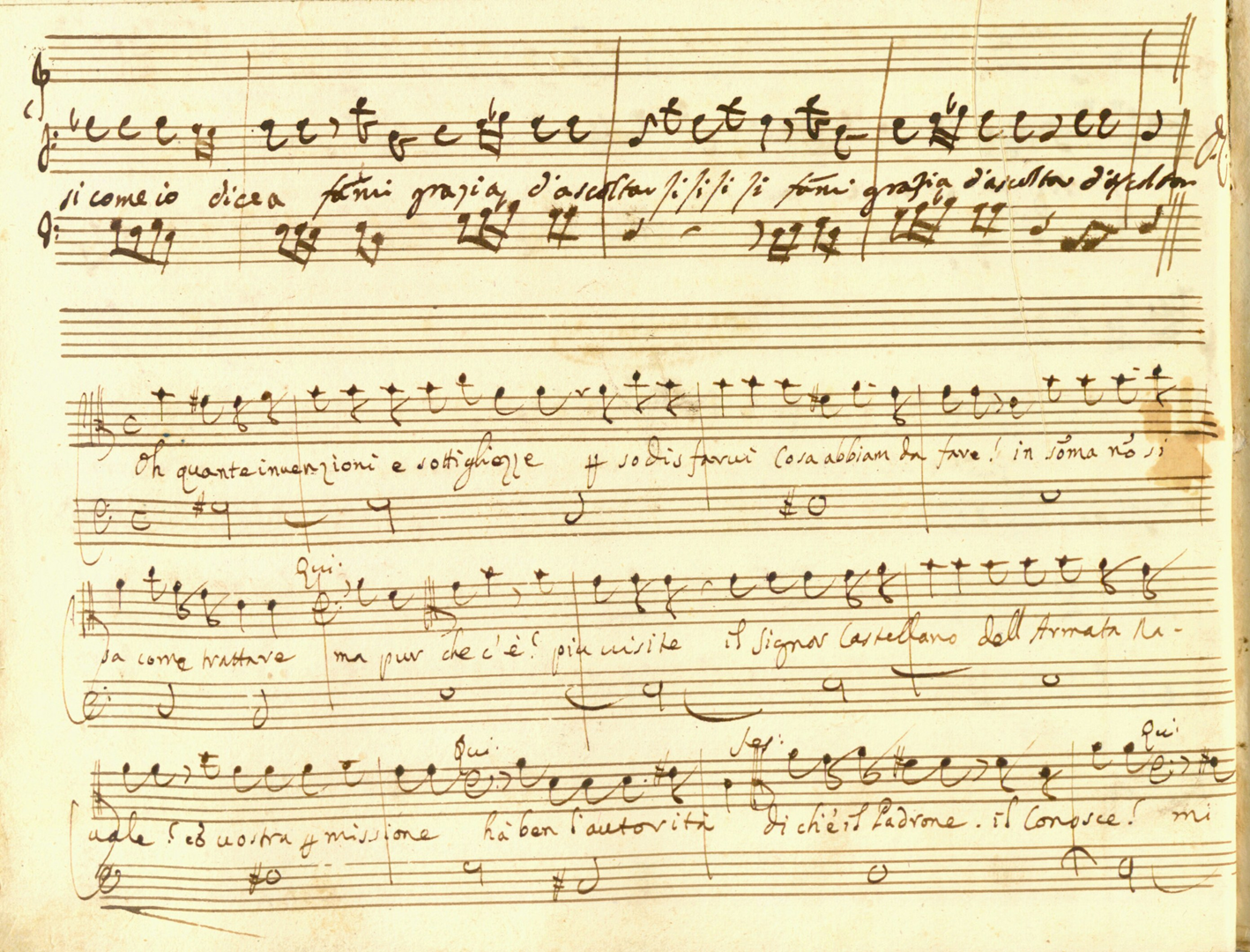

Now let us turn to some of the instances of these graphic indications that may be linked to solfeggio practice. The first occurs in Act 1 Scene 5 of La fede tradita e vendicata, in Lesbina's aria ‘La speranza ch’è donzella’ (fol. 13r), partially reproduced in Figure 3. This aria is from a comic scene, sung by a comic interpreter.

Figure 3 Francesco Gasparini and Giuseppe Vignola, aria ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, La fede tradita e vendicata, Act 1 Scene 5, bars 11–12. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella, Naples (I-Nc), Rari 6.7.13, or 32.3.30, fol. 13r

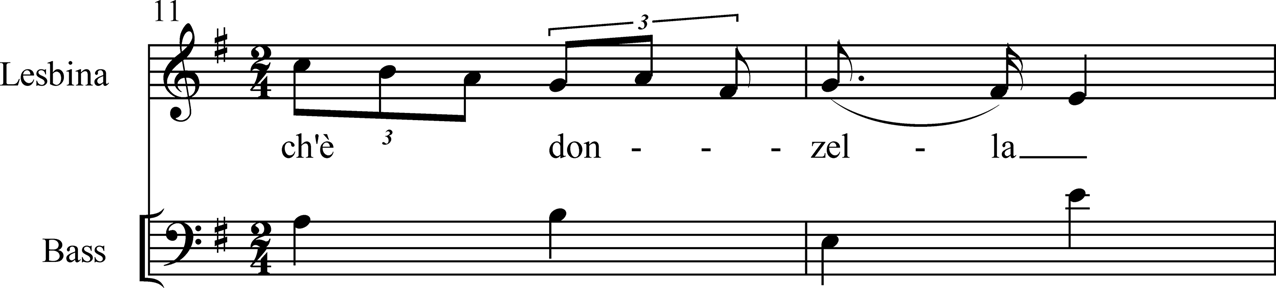

What caught my attention is the separate beaming at the end of bar 11 and the slur between the G and F♯ of bar 12 (soprano clef). Indeed, the copyist could have joined the beaming between the dotted quaver and the following semiquaverFootnote 16 to indicate the syllabic prolongation. In addition, the last note of the triplet at the end of bar 11, an F♯, would indicate a wrong syllabic setting, for each separation of beaming in these manuscripts indicates a change of syllable. Example 3 renders this passage in a modern score according to the actual beaming given in Figure 3.

Example 3 Vignola, ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, bars 11–12, first attempt at a modern rendition

This is wrong in all respects, because of stresses. The verse structure must follow the mandatory ottonario accents,Footnote 17 as shown here:

The seventh syllable, ‘-zel-’, is a stressed syllable and cannot fall on a weak beat, which in Example 3 coincides with the last quaver of the second triplet in bar 11. As a conclusion, ‘-zel-’ needs, in any case, to fall on the G of bar 12, for the first triplet in bar 11 is entirely occupied by ‘ch’è’ and the other separate beaming, between the two triplets, implies that ‘don-’ should be placed on G. The closer subsequent strong beat is the G of bar 12. Thus, considering the detached F♯ as inessential to the syllabic distribution, the passage would be as shown in Example 4.

Example 4 Vignola, ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, bars 11–12, second attempt at a modern rendition

The syllable ‘-zel-’ is now in the right place, on a strong beat. However, another strange thing happens. It is very odd that the last syllable, ‘-la’, is placed on the F♯ and not on the E. The copyist must have noticed this, and therefore added a slur, to indicate that the ‘-zel-’ syllable was to be prolonged over G and F♯. He probably just made a mistake while copying and did not want to waste time in correcting the error by scraping the paper. The function of the slur is thus clarified: it is needed to correct the copying error and the slur, in a modern edition, could be replaced by a beam. In conclusion, Example 5 gives the definitive version.

Example 5 Vignola, ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, bars 11–12, third and final attempt at a modern rendition

As the reader will have noticed, the F♯ has still a separate beaming. This is strange, because the most probable syllable positioning for this passage is depicted in Example 5. If that separate beaming does not imply a syllable separation, what does it mean? Is it a banal copying mistake? And, if so, why did the copyist not correct it, if he corrected the separate beamings of bar 12? I believe that this separate beaming has a deeper meaning, related to solfeggio practice. Let us examine the solmized vocal line of this passage, whose probable rendition is manifested in Example 6.

Example 6 Vignola, ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, bars 11–12, solmized vocal line

The fact that the common descending fa–re hexachord pattern in the Re mode (corresponding to a modern minor key) emerges here shows that every note in Lesbina's staff which is not present in the solmized line can be considered an embellishment of the main solmized syllables. This would explain the detached F♯. It could have been indicated as such to make the descending hexachord pattern clearer to the singer, to isolate the main solmized syllable (F♯, ‘mi’) and to signal the A of the second triplet in bar 11 as an embellishment of G (‘fa’). All of these features would have been hidden by a united beaming. The comparison between the solmized line and Lesbina's staff manifests another important point related to the three descending notes of bar 12. The main solmized syllable, ‘re’, corresponds to E. The G and F♯ in Lesbina's staff are two ornamental notes. Indeed, these two notes could be considered as a simple illustration of the solfeggio Appoggiatura-rule. Thus the abovementioned slur (Figure 3 and Examples 3 and 4, bar 12) between G and F♯ could also indicate that all the three notes (G, F♯ and E) should be sung as ‘re’ and not as ‘fa mi re’, the first two of which had already been sung before.

This example has shown that, contrary to what is traditionally thought of slurs and beaming, these graphic indications could contain other information. Before passing on to the next case study from the same score, it is worth acknowledging a further interpretation of the same passage, which is, I believe, unlikely. In this version, the syllable ‘don-’ would fall on the F♯ that lacks beaming, and this would justify this very separation. However, there should then have been a beam joining the A and the G of bar 11, which is absent. Moreover, the aria is generally coherent in placing every syllable on every beat when a similar descending contour with triplets is present, such as in Figure 4 (soprano clef).

Figure 4 Vignola, ‘La speranza, ch’è donzella’, bars 17–18, fol. 13r

The three syllables of ‘vi saprà’ (‘vi sa-prà’) each occupy one crotchet. If the last interpretation of our detached F♯ were correct, we would expect the last note of bar 17 to have a detached beaming, but this is not the case. On the contrary, for the very reason that this passage features the same notes as Example 5, but with different beaming, and that Figure 3 is the first occurrence of this kind of pattern in the aria, it could be that only on the first occurrence of that pattern was the solmized line indicated, in order to facilitate reading. Then, as regards the succeeding instances, such as that in Figure 4, it was no longer necessary, since the solmized reading would have been automatic. All of these elements confirm in hindsight the theory set out in this paragraph.

A similar occurrence of the same peculiar use of beaming, which will not be explained in detail here, can be found at fols 23v–24r. The excerpt, a comic duet from Act 1 Scene 8, is shown in Figure 5 (the vocal line is to be read in tenor clef, since this is Milo's part). The syllable-prolonging horizontal line suggests that the ‘-sì’ of ‘co-sì’ should be maintained until C of bar 6:Footnote 18 why, then, does the beaming separate D and C? This separated beaming could be a graphic aid for the singer, who would need to change the solmized syllable from ‘fa’ (reached with the first F of bar 5) to ‘do’ (C at the end of bar 6). In other words, E and D become ornaments of the first ‘fa’ (F) of bar 6.

Figure 5 Gasparini and Vignola, duet ‘Perché, mercé, così’, La fede tradita e vendicata, Act 1 Scene 8, bars 4–7, fols 23v (left)–24r (right)

One question arises. The manuscript of La fede e tradita e vendicata is a bella copia (fair copy), not a score of habitual use. Neapolitan operatic full primary sources (not single-instrument parts) could be divided into these two main categories: fair copies and habitual-use ones. The first consists of ‘clean’ manuscripts, without corrections and erasures. In some cases they are very elegant, for they were meant to be part of some nobleman's private collection. Performers were not likely to use them.Footnote 19 Scores of habitual use, on the other hand, are full of corrections, sometimes evidently added during rehearsals. These latter, from a philological perspective, are usually more important than the first; in general, it is easier to find fair copies than habitual-use scores, but both types are sufficiently represented in the relevant libraries. Why should the introduction of solfeggio practice ‘help’ in a fair copy? To seek an answer to this question, several elements need to be considered. In the first instance, as noted earlier, the performers of comic scenes were less musically advanced than their opera-seria counterparts: sometimes they were even commedia dell'arte actors who were more or less capable of singing.Footnote 20 Thus it would make sense that scores destined for them would have more practical instructions. This peculiar usage of beamings and slurs is relevant for another reason: it might provide a basis for improvised performance. In other words, once the comic singers identified the solfeggio pattern in the piece, they did not need to learn the score exactly. The score fades, becoming just an exemplar of good taste in performance, a commedia dell'arte canovaccio on which to improvise.

This may seem to be an irrelevant consideration, since the question arises as to why and whether the comic performers would have had access to a ‘clean’ score copy. However, the production of Neapolitan operatic scores was rarely a straightforward process: there are cases where the ‘fair copy’ actually conflates a proper fair copy and a score for use. Such is the case, for instance, with Domenico Sarro's ‘fair copy’ of Lucio Vero.Footnote 21 If one compares the difference between the recitative in fols 51r–53r and the aria in fols 53v–57v, the hasty handwriting and the erasures, added perhaps during rehearsals, suggest that the aria was written down at a ‘score-of-use’ stage, whilst the neat handwriting of the recitative points to the opposite situation. In fact, fol. 57v, shown in Figure 6, presents both handwritings: this suggests that the manuscript was composed in two stages. The first consists of the ‘fair copy’ of the recitatives, amongst which some blank pages were left to add the arias, which, however, might have been written down at a non-fair-copy stage. Returning to La fede tradita e vendicata, a coherent fair copy, it is likely that the copyist might have had, as his source, a score similar to Lucio Vero, or an entire working score covered in confused erasures and markings. It is also possible that he could have started from the single instrumental and vocal parts, distractedly retaining some notational aids not meant to appear in a fair copy. In any case, my suggestion remains valid, because these notational features, possibly hinting at a lost solfeggio culture, are present only in the comic arias.

Figure 6 Domenico Sarro, Lucio Vero. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella, Naples (I-Nc), Rari 1.6.25, or 18.4.1, or 14.7.33, fol. 57v

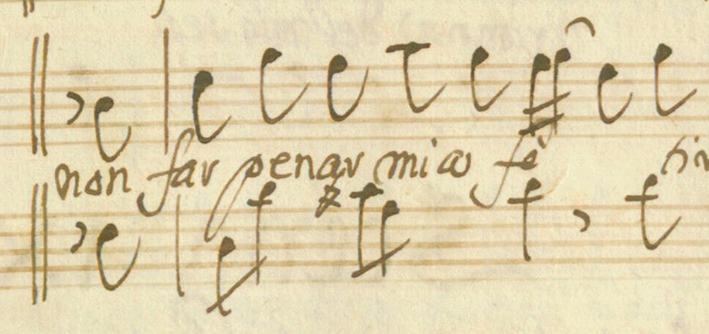

A second case study from La fede tradita e vendicata can be found as Figure 7 (the vocal line is to be read in the tenor clef, as this is once again Milo's part). The passage is from a comic duet (Act 1 Scene 8). As can be clearly seen, there is a slur over three notes: E, F and D. This could be possibly linked to the necessity of extending a syllable over the three notes, the last of which has a detached beaming. However, the copyist could have united the beaming to convey the same thing. This would not have entailed a complicated scraping operation, but simply the addition of a horizontal line between F and D to join the two notes. Example 7 presents Figure 7 in modern notation.

Figure 7 Vignola, ‘Perché, mercé, così’, bars 31–32, fol. 25r

Example 7 Vignola, ‘Perché, mercé, così’, bars 31–32, copyist's version

If the solmized line is considered, a very common pattern appears, akin to Robert Gjerdingen's Do Re Mi. The first stage corresponds to the first beat of the bar, which presents a D minor root-position chord and D in the melody; the second stage, on the second beat, superimposes a melodic E on a dominant(-seventh) chord, while the third beat brings the third stage, with a melodic F together with a further chord of D minor. Example 8 presents the same excerpt with the solmized line superimposed, together with a ‘simplified’ bass line according to Gjerdingen's theory.

Example 8 Vignola, ‘Perché, mercé, così’, bars 31–32, copyist's version with solmized line and simplified bass

The fact that the solmized line that emerges is also one of Gjerdingen's schemata speaks well for its plausibility. Thus, as in the previous case, everything else is embellishment. As regards the first two beats of bar 32, the addition of an ornamental upper third to the solmized syllable is a common embellishment technique. The most interesting part concerns the last four notes of Milo's vocal part. E, F, D and F could be an embellishment of the ‘fa’ syllable (which, in this case, is also a ‘true’ ‘fa’, an F). Since the final note here is set to the syllable ‘ti-’, it should be clarified that solfeggio syllables do not necessarily go along with the syllables found in the lyrics, and vice versa. See also, for instance, bar 6 of Example 9 below. The solmized syllable underpinning the three initial notes (C, B and C) is ‘fa’, where B is a simple ornament of C, yet the syllable in the lyrics changes, from ‘La-’ to ‘-bro’. Returning to Example 8, the slur above E, F and D could indicate a prolongation of the syllable, but it could have a further meaning. If the syllable were only to be prolonged, the copyist could have added a simple line between F (semiquaver) and D (quaver), to unite the beaming: this would not have required a complex scraping operation. Instead, he added a slur. Thus, once more, this slur could have another meaning linked to solfeggio practice. In this case, it could have indicated to the singer that E, F and D are only ornamental notes, and that the ‘true’ solmized note was F, ‘fa’. All the reasons cited above why these elements should be present in a fair copy are valid also in this case, as well as the ones relative to the kind of singing capabilities of comic performers. Here we have an obscure Amato Vacca, not a Farinelli, as interpreter. The fact that the meaning of this slur is very similar to that of Figure 3 – it signals the presence of ornamental notes – seems to indicate that this kind of ‘solfeggio’ slur might coincide with traits of vocalization characteristic of solfeggio practice.

Example 9 Vignola, ‘Labro candito’, bars 6–9, copyist's version

A third occurrence of a similar graphic indication is Milo's aria ‘Labro candito’ (Act 2 Scene 11). An excerpt where the graphic elements are present can be seen in Figure 8. Before proceeding with an analysis, it is worth mentioning that the second word reproduced here is written as ‘candido’ instead of ‘candito’. This might be an error. Since expressions such as ‘candide labbra’ (pure/young/naive lips) are very common in Italian opera, I believe the issue is worthy of clarification. Even though ‘candido’ appears twice on fol. 58v, several elements suggest that this is a copying error. First, as emerges from the libretto, where ‘candito’ is present, the whole aria is organized in quinario lines (five-syllables lines which need an accent on the fourth syllable): ‘càndido’, a sdrucciolo word, would not fit. Second, intermezzos teem with sugary food metaphors. Take the passage from the aria ‘Brusar pe me ti sento’ from the intermezzo La franchezza delle donne by Giuseppe Sellitti (Naples, 1734).Footnote 22 Sempronio, singing a love aria in Venetian dialect, maintains that Lesbina's face is covered in sugar and is like biscuit dough.

Third, the recitative preceding Milo's aria, shown below, had already introduced the food-related topic.

Figure 8 Gasparini and Vignola, aria ‘Labro candito’, La fede tradita e vendicata, Act 2 Scene 11, bars 6–9, fol. 58v

Lastly, this aria discloses a clear AABCB rhyme scheme, mirrored also in the second stanza of the aria: ‘candido’ would alter the inherent rhyme structure.Footnote 23 In the case of a deliberately inserted ‘candido’, a wrong syllabic setting would emerge. The overall piece is notated in 3/4, yet some bars, such as Figure 9 shows, are actually in 6/4. This suggests that the whole aria should be considered in 6/4, not 3/4. It would follow that the accented syllable of ‘càndido’ would fall on a weak beat, the D of bar 6 (refer to Example 9). Does this metrically incorrect ‘candido’ have deeper meanings, perhaps linked to the desire of making comedy arise from a badly pronounced word?

Figure 9 Vignola, ‘Labro candito’, bars 16–19, fol. 58v

Now let us turn to the analysis of the two slurs present here. Example 9 shows an adapted modern transcription of the excerpt in Figure 8. It retains, however, the original positioning of the slurs.

Let us start from the second slur, in bar 9, as it is easier to understand. The copyist, as can be seen in Figure 8, indicated the syllable prolongation through a straight line between ‘-ti-’ and ‘-to’. Moreover, the two quavers are already united by the beaming: adding a syllabic slur would be superfluous. Thus I believe that the slur refers to solfeggio practice. It is indicating to Amato Vacca, Milo's first interpreter, that the solmized notes in bar 6 are the first E and the final D (‘mi’ and ‘re’ respectively), not the two quavers. In bar 7 an identical situation emerges. That the syllable positioning of bar 7 is correct in Example 9 could be deduced from bar 9, which consists of the same notes and which sets two syllables, the first stressed and the second unstressed (same syllabic situation), precisely with a straight line. Thus it would follow that the slur should go over the two quavers, since the syllabic situation is similar. In this case, I believe, we see an error by the copyist, who should have positioned the slur over the quavers. In this case, moreover, the slur cannot be a syllabic one, because of the similarity of accents and syllable disposition with bar 9. It would be nonsense, in other words, to indicate a syllable prolongation between the E quaver and D crotchet of bar 7, because the syllable changes. As Baragwanath's studies have proved, moreover, solfeggio traits of vocalization are often carelessly placed.

It could be argued that the carelessness with which such slurs were sometimes placed might weaken this essay's findings. Notwithstanding that this might be true in a general sense, the two case studies involving slurs (Figures 7 and 8) avoid this problem. In Figure 7, for instance, the slur might be interpreted as joining only the F semiquaver and D quaver, instead of E, F and D. The examination of Figure 3 suggests that beaming could serve as a graphic solfeggio aid as well. In other words, whether E and F, joined by a beam, are united by beaming or by a slur would not make a difference, at least in this case: the slur signals to the singer that E, F and D pertain to the same solfeggio syllable. As regards Figure 8 and Example 9, which one is the carelessly positioned slur? It might be argued that the correct slur is the first one, not the second. An example from the solfeggio repertory might be of help. Consider the solfeggio by Leo shown in Figure 10, along with its modern transcription in Figure 11.

Figure 10 Leo, Solfeggi di soprano. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella, Naples (I-Nc), 34.2.6/2, fol. 38v, bar 1

Figure 11 Leo, Solfeggi di soprano, fol. 38v, bar 1, transcribed in Baragwanath, The Solfeggio Tradition, 141

The solfeggio slur in bar 1 prolongs the syllable ‘do’ over the subsequent beamed E and D, yet this slur appears only above E and D. This is exactly what happens in Figure 8 and Example 9. To indicate that the syllable ‘mi’ is to be prolonged also to F and E quavers of bar 9, the slur is positioned over the subsequent two beamed notes. This similarity with a solfeggio source suggests that the correct slur is the one in bar 9, rather than the one in bar 7.

A similar use of slurs has emerged through the study of the comic scenes included in an opera entirely by Vignola, Tullo Ostilio (Naples, 1707), whose manuscript is another ‘fair copy’.Footnote 24 Example 10 shows an excerpt from Act 3 Scene 10, a duet between the comic characters Dorinda and Milo. As should be evident, the solfeggio slurs in the soprano staff present in most bars indicate that the combinations of two semiquavers and one quaver (for instance, B♭–C–D in bar 44) are to be sung to the same solfeggio syllable. This suggests that the manuscript of La fede tradita e vendicata is not the only preserved operatic ‘fair copy’ manifesting (and, perhaps, retaining from an early working score) solfeggio ‘aids’.

Example 10 Vignola, duet ‘Balliamo, saltiamo’, Tullo Ostilio, Act 3 Scene 10, bars 44–48. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica Giuseppe Verdi, Milan (I-Mc), Noseda F 81, fols 268v–269r

This essay has illustrated the possible presence, in the comic scenes included in the manuscript of La fede tradita e vendicata, of a particular usage of beamings and slurs which could reveal deeper meanings related to solfeggio practice. At first glance, these might seem to be mere copying errors or uncertainties, but, if analysed more carefully, they appear to constitute a sort of notational aid for the singer, meant to differentiate the main solmized notes from embellishments and to help the performer easily to identify the solfeggio patterns. The beaming and slurs in these case studies, taken from the comic scenes of a particular operatic manuscript, show quite clearly, I believe, an early stage of solfeggio training, probably the stage reached by comic singers. This kind of singer, as already pointed out, was more likely to be an experienced actor than a learned musician, and their singing abilities were secondary, not comparable to those of an opera-seria virtuoso. These findings offer an insight into how comic singers approached the study of their arias. It was easier to conceive them as a chain of solfeggio patterns, rather than to sing them by reading note for note.

This evidence might offer further insights into the question of how schematic thinking manifested itself in musical practice. Gjerdingen implies it from analyses of different repertories; partimento and solfeggio studies deal with didactic material. My study, having discerned documentary evidence of schematic thinking in operatic manuscripts, adds, in a small way, to the overall picture.

Another conclusion concerns musical philology. Since the essay has shown that beamings and slurs could have a deeper meaning linked to solfeggio practice, I believe that they should be considered more carefully, not regarded as mere copying errors. If carelessly corrected or eliminated in a modern edition, something that the original text is trying to tell would be lost.