1 Introduction

Scientific advances have made it possible to measure time to an accuracy of about one second error in approximately 30 million years. However, beyond its measurement, time continues to be one of the most difficult properties of the universe to be understood. Elusive to the human senses, time is a highly abstract concept whose conceptual representation seems to be largely dependent on space and motion (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999: 129; Evans Reference Evans2004: 14; Núñez & Sweetser Reference Núñez and Sweetser2006; Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky, Dehaene and Brannon2011). In language, time is often described in spatial terms. In English, for example, expressions such as back in the day, medicine was not as developed as it is today or Brexit will test the resilience of the British economy in the years ahead abound in the usage of speakers when they talk about past and future events. Research has shown that such vocabulary choices are not random but systematic, and that they are widely spread across most world languages (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997: 1; Dancygier & Sweetser Reference Dancygier and Sweetser2014: 168–9). The spatialization of time is argued to be motivated by conceptual metaphor, a cognitive operation that serves an epistemic function by helping us to understand, reason and talk about an otherwise abstract, complex, subjective or unfamiliar notion (target domain) by relating it to another notion that is perceived as more concrete, well-structured, simple or familiar (source domain) (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999: 45).

In this context, drawing on Conceptual Metaphor Theory, this article examines Old English (OE) vocabulary of time to explore how time, space and motion were metaphorically intertwined in the conceptualization and description of time in the Old English period. The aim of this article is to shed light on the historical and sociocultural dimensions of space–time metaphors in English, in particular the spatialization of time along the circular, vertical and sagittal axes, and add to previous research on the metaphorical conceptualization of time in Old English, which so far has mainly focused on the study of isolated terms such as first ‘first’, hwil ‘while’ and fæc ‘space, interval’ (Kopár Reference Kopár, Hall, Timofeeva, Kiricsi and Fox2010), and the analysis of the concepts of future, temporal flow and eternity (Yang Reference Yang2020).

This article is structured as follows: section 2 offers an overview of the most significant theoretical and experimental findings on the metaphorical conceptualization of time in Modern English. Section 3 analyzes how native sociocultural conventions and cross-cultural contact might have contributed to shaping time conceptualization in early medieval England. Section 4 provides a description of the materials and methods used in this study and section 5 analyzes the predominant space–time metaphorical mappings found in OE vocabulary, illustrates them with examples and discusses their cultural and experiential roots.

2 The axes of time in Modern English

The metaphorical projection of time onto space is rather flexible. In English, there exists linguistic and experimental evidence that the lateral (left/right) and sagittal (front/back) axes are recruited to spatialize time. Timelines and calendars in western cultures are graphical representations of a metaphor that maps time onto the lateral axis in a left-past, right-future fashion. This metaphorical conceptualization of time coexists with a back–front spatial metaphor that maps past and future onto back and front locations, respectively, and conceptualizes the passing of time as forward movement (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 42). The former metaphor has no explicit linguistic manifestation in English or in any other oral language (Radden Reference Günter, Baumgarten, Böttger, Motz and Probst2004); however, its psychological reality has been supported by many studies. For example, research has shown that the categorization of past and future related words or events is facilitated when stimulus and/or response positions are congruent with the left-past, right-future conceptual metaphor (Torralbo, Santiago & Lupiáñez Reference Torralbo, Santiago and Lupiáñez2006; Santiago, Lupiáñez, Pérez & Funes Reference Santiago, Lupiáñez, Pérez and Funes2007; Fuhrman & Boroditsky Reference Fuhrman and Boroditsky2010). Likewise, the analysis of temporal co-speech gestures (Cooperrider & Núñez Reference Cooperrider and Núñez2009; Casasanto & Jasmin Reference Casasanto and Jasmin2012) and behavioral experiments, where participants are asked to arrange cards that represent events in temporal order (Tversky, Kugelmass & Winter Reference Tversky, Kugelmass and Winter1991; Bergen & Lau Reference Bergen and Lau2012), also provide evidence that English speakers tend to conceptualize time as moving from left to right. This spatialization of time seems to be culturally determined. The direction in which a language is predominantly written (Tversky, Kugelmass & Winter Reference Tversky, Kugelmass and Winter1991; Bergen & Lau Reference Bergen and Lau2012) as well as the layout of cultural artefacts used to reckon time (e.g. calendars) have been shown to influence how time is represented (Duffy Reference Duffy2014). In western cultures, where written texts and calendars are displayed from left to right, speakers tend to locate the past on the left and the future on the right. In contrast, in the case of languages that are written right to left, such as Hebrew or Arabic, or top to bottom, such as Mandarin, the spatial representation of time is adjusted to writing practices (Fuhrman & Boroditsky Reference Fuhrman and Boroditsky2010; Bergen & Lau Reference Bergen and Lau2012).

The back–front time metaphor shows two realizations. In one of them (the ego-based metaphor) the ego is taken as the reference point and the present moment collocates with the ego's location, so now is the ego's location, past is behind the ego and future is in front of the ego. This metaphor has, in turn, two subcases: (a) the ego-moving metaphor, where time is understood as a static metaphoric landscape and the ego as an entity moving forward from the present towards the future – e.g. We are fast approaching the deadline; and (b) the time-moving metaphor, where time is conceptualized as an entity moving along a path from future through present towards past and the ego as a static observer – e.g. the deadline is approaching (Núñez & Cooperrider Reference Núñez and Cooperrider2013; Dancygier & Sweetser Reference Dancygier and Sweetser2014: 169). In the second realization of the front–back metaphor, no anchoring to the present moment exists and time relationships are set on the basis of the relationship of one temporal event to another with earlier events in front of later events as in June follows May (Núñez & Sweetser Reference Núñez and Sweetser2006; Moore Reference Moore2014: 109–10). This non-deictic time-based model is found in ancient Indo-European languages (Bartolotta Reference Bartolotta2018).

The gestures that cooccur with temporal expressions, when people gesture deliberately, are congruent with the front–back spatialization of time as people tend to gesture towards the front when talking about the future and towards the back when talking about the past (Casasanto & Jasmin Reference Casasanto and Jasmin2012). There is also evidence that front–back spatial representations are recruited to think about time (e.g. when locating events in time) and that whether the ego-moving or time-moving model of time representation is used depends on what spatial representation is most cognitively available at that moment, either because it is primed by the immediate environment or because culture primes it more generally (Boroditsky Reference Boroditsky2000). This metaphor is not universal either. In Aymara and other related languages, for example, past events are placed in front and future events are placed behind (Núñez & Sweetser Reference Núñez and Sweetser2006).

The use of the vertical axis as a source domain for time conceptualization is particularly prolific in languages such as Chinese; however, it is much less frequent in English (Radden Reference Günter, Baumgarten, Böttger, Motz and Probst2004). Its use is restricted to idiomatic expressions such as it is high time or it comes down from our ancestors where earlier is up and later is down, while in expressions such as the new year is coming up or to update future/later events are up/higher. Psycholinguistic studies suggest that, although both the sagittal and the vertical axes participate in time conceptualization in English, English speakers are more likely to arrange time transversally than vertically in time–space tasks (Boroditsky, Fuhrman & McCormick Reference Boroditsky, Fuhrman and McCormick2011; Fuhrman et al. Reference Fuhrman, McCormick, Chen, Jiang, Shu, Mao and Boroditsky2011). Finally, English also shows traces of a circular representation of time that manifests itself in fossilized expressions such as all the good times are coming round again or the years/days go round in circles.

Such metaphorical diversity has been attributed to the multifaceted origin of metaphors, which can stem from our bodily, linguistic and cultural experiences (Kövecses Reference Kövecses2005: 17–32; Casasanto Reference Casasanto, Landau, Robinson and Meier2014). The conceptualization of time as motion along the front–back axis appears to be grounded in our embodied experience of motion (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 58–9) and strengthened by conventional linguistic expressions such as the day will come when things will change or the years we have left behind. The use of the lateral axis (past-left/future-right), however, is more consistent with culture-specific time–space correlations derived from reading and writing patterns and artifacts for time reckoning and representation (Ouellet et al. Reference Ouellet, Santiago, Israeli and Gabay2010; Núñez & Cooperrider Reference Núñez and Cooperrider2013; Casasanto & Bottini Reference Casasanto and Bottini2014; Duffy Reference Duffy2014). The metaphorical mapping of future events onto the vertical axis, according to Lakoff & Johnson (Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980: 16), is grounded in our perceptual experience and the fact that as we get closer to an object it seems to rise up in our visual field, which results in the metaphor future is up. The metaphor later is up/high is also argued to be connected to the functioning of our visual system and the experience that points located further along a path appear to be higher than those that are close to us. Finally, recurrent cycles in nature and culture are said to account for the circular representation of time (Radden Reference Radden, Brdar, Omazić, Takač, Gradečak-Erdeljić and Buljan2011).

As our sensorimotor, cultural and linguistic experiences are susceptible to change over time, metaphors, far from being understood as a monolithic set of correspondences between two domains of experience, must be seen as flexible conceptual projections sensitive to cultural variation (Kövecses Reference Kövecses2005: 67). Although some metaphors may remain part of a language for thousands of years, sometimes with varying degrees of salience (long-term metaphors), others may disappear or become inactive over time (short-term metaphors) due to, among other factors, cross-cultural contact and shifts in the system of values and beliefs held by speakers (Trim Reference Trim2011: 74). Research on the metaphorical conceptualization of time, for example, has shown that its conceptualization as a valuable object has changed over time. Medieval theocentric worldviews prompted a conceptualization of time as a precious gift of God whose use was evaluated at Judgment Day, leading to either eternal life or damnation. The secular anthropocentric cultural paradigm adopted by the late Middle Ages progressively led to the emergence of a new understanding of time as a resource or commodity for obtaining material goods rather than as a means for achieving eternal life (Konnova & Babenko Reference Konnova and Babenko2019). This shift in the value system has influenced the relative salience of both metaphors, with the former losing ground against the latter over time. This medieval change in the conceptualization of time as a valuable object makes it clear that cultural variation may lead to the obsolescence of a metaphor or to fluctuations in its use and frequency (Trim Reference Trim2007), which calls for an examination of the earliest attestations of time words in English to understand how time used to be conceptualized and evaluate to what extent current space–time mappings in English are a continuation of that conceptualization.

3 Time in early medieval England: an overview of previous research

The study of OE vocabulary of time has shown that English had a vast repertoire of terms to convey time-related notions (Bately Reference Bately and Bammesberger1985) and that they were organized around three main groups (Sauer Reference Sauer2003): (a) words that exclusively referred to time notions (e.g. gear ‘year’, wucu ‘week’); (b) words that denoted Christian festivals and saints’ feasts and also served as time terms (e.g. Christmas or Easter); and (c) words that named meals and were metonymically used as time words (e.g. underngeord, undernmete ‘breakfast’). These lexical devices enabled OE speakers to describe time at different levels of specificity, ranging from very vague time indications (e.g. hwīlum ‘at times’) to well-defined points in time (e.g. sunnanūhta ‘the time before daybreak on Sunday’) (Bately Reference Bately and Bammesberger1985). Likewise, time could also be rendered at different levels of concreteness, which differ across genres, with poetic texts showing a more concrete construction of time than philosophical (scientific) texts mainly thanks to the use of metaphors (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko, Bolognesi and Steen2019).

The analysis of OE time words has also suggested that, in early medieval England, different ways of understanding time coexisted and that they were dependent on factors such as (a) how time was measured and recorded, (b) the uses to which time reckoning was put (Liuzza Reference Liuzza2013) or (c) the influence of pagan and Christian cultural conventions (Yang Reference Yang2020: 75). Nature's cycles such as the alternation of night and day, the waxing and the waning of the moon, the position of the sun as it moves across the sky and seasons seem to have been among the earliest time reckoning methods used in early medieval England as reflected in OE literary records (Skeat Reference Skeat1884; Nilsson Reference Nilsson1920: 293–7). As for the uses to which time reckoning was put, the pre-Christian lunar calendar used in England seems to have served as a guide to seasons for farmers and stockbreeders (Harrison Reference Harrison1973) and also to rituals and festivals. This would explain why the names of some months correlated with seasonal agricultural activities (e.g. þri-milcemonað ‘the month when cows were milked three times’, ‘May’) or with the names of the goddesses to whom sacrifices were offered in that time of the year (e.g. hreð-mōnaþ ‘April’ is said to derive from the name of the goddess Rheda). Finally, the adoption of Christian traditions in the early OE period has been argued to represent a turning point in the way time was conceptualized (Yang Reference Yang2020: 75-6). ‘The Christian belief in the birth, Crucifixion and death of Christ as unique, unrepeatable events made people regard time as a linear path that stretches between past and future’ (Lee & Liebenau Reference Lee and Liebenau2000: 44). Hence, while pre-Christian cultures are said to mainly resort to nature-determined cyclical time models (Russell Reference Russell1994: 176; Urbańczyk Reference Urbańczyk and Carver2003), the Christian conceptualization of time is linear (Driscoll Reference Driscoll, Driscoll and Nieke1988; Urbańczyk Reference Urbańczyk and Carver2003) and is grounded in cultural rather than natural factors. Christianity is also argued to have brought to England the concept of future (Yang Reference Yang2020: 29). This argument builds on the claim that ancient Germanic peoples had a binary time system that divided time into past and non-past, that is, into what had already happened and what was in the process of happening. In this time system, the concept of future would not exist. It would instead be part of the present (Bauschatz Reference Bauschatz1982: 141–2).

The characteristics of the OE verb system have been said to support this view since OE verbs were inflected for only two tenses, present and preterit. However, it should be noted that in Old English the present tense was used to express future time, with adverbs added to avoid ambiguity (Curme Reference Curme1913; Traugott Reference Traugott and Hogg1992: 180).Footnote 2 This suggests that a conception of future existed, even though it might have been different from that in the Christian tradition, where the notion of future was understood as the end of time.

Beyond the potential influence of the Christian conceptualization of time on the OE time system, the intercultural exchanges of the Anglo-Saxons, the Romans and Celts might have also influenced their time conceptualization. There is linguistic and artistic evidence that time–space correlations consistent with the metaphors before is above, after is below, the past is behind and the future is in front (of the ego) stretch back to ancient Roman culture (Short Reference Short2016) and that the influence of Old Irish Gaelic on OE might explain the cyclical structure of the Menologium, a tenth-century OE metrical calendar (Hennig Reference Hennig1952).Footnote 3

In this context, the aim of this article is to reconstruct the space–time cognitive models used in the Old English period to understand and convey time notions to add to previous literature on the study of OE vocabulary of time and gain a deeper understanding of the historical basis of Modern English space–time metaphors.

4 Materials and methods

This study is based on data extracted from the printed and online versions of the Thesaurus of Old English (TOE) (Roberts, Kay & Grundy Reference Roberts, Kay and Grundy2000, Reference Roberts, Kay and Grundy2017); The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the online edition of the Bosworth–Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (B–T) (Bosworth & Toller Reference Bosworth and Toller1882–98); A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Clark-Hall Reference Clark Hall1916); The Dictionary of Old English A to I (DOE) (diPaolo Wilkin & Xiang Reference diPaolo Healey, Wilkin and Xiang2018); and the Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus (DOEC) (diPaolo, Wilkin & Xiang Reference diPaolo Healey, Wilkin and Xiang2009), from which all the examples used to illustrate our analysis have been extracted. In order to identify how time was metaphorically intertwined with space and motion in the Old English period, we first searched for all the words referring to time (05.11)Footnote 4 in the TOE and identified lexical overlaps between this domain and the domains of space (05.10)Footnote 5 and motion (05.12).Footnote 6 Then, to determine the metaphorically used words, we applied an adapted version of the metaphor identification procedure (MIP) (Pragglejaz Group 2007), which identifies a metaphor when a lexical unit has a more ‘basic meaning’ in other contexts than in the context that is being analyzed and understands basic meanings as more concrete, related to bodily actions, more precise or historically older (Pragglejaz Group 2007). Using the DOEC, we searched for examples consisting of the target words and their co-texts. Examples were read to establish a general understanding of their meanings and to determine the meaning in context of the words under analysis. Then, the OE dictionaries listed above as well as the OED were used as a reference to establish basic meanings and to evaluate whether the temporal meaning of the words being analyzed could be understood via a comparison with a more basic meaning related to the more concrete domains of space and motion. We took the concrete–abstract directionality of metaphorical extensions, their systematicity (i.e. the instantiation of those concrete–abstract metaphoric mappings in multiple words) and etymological semantic information as a clue to a metaphorical connection between domains. For example, the adverb and preposition bufan is listed under the semantic categories time and space in the TOE. Its temporal sense, according to the B-T and the DOE is ‘more than, older’ as in fram twentigum wintrum & bufan ‘from twenty years & over that’ (DOEC, Num, [0009 (1.45)]) while its spatial sense is ‘above’ as in Gif se earm bið forad bufan elnbogan ‘if the arm is fractured above the elbow’ (DOEC, LawAf 1, [0130 (54)]). Following the MIP, the spatial sense of the word, being historically older, as it is a derivative word that ultimately comes from the PIE root *upo ‘up from under’, ‘over’, and being more concrete, should be established as its basic meaning. Its use as a temporal preposition is interpreted as an example of metaphoric transfer from concrete to abstract subsumed under the metaphorical pattern later is up, where bufan introduces a point in time later than that indicated by the accompanying temporal unit.

The adopted methodology identifies metaphorical links between concepts as a function of the proportion of unique overlapping words between semantic domains rather than as a function of frequency. The rationale behind this procedure, also applied in the Mapping Metaphor with the Historical Thesaurus project (2015), is the observation that metaphors and metonymies can be identified from lexical overlaps between semantic areas (Anderson, Bramwell & Hough Reference Anderson, Bramwell and Hough2016); and that this methodology helps to deal with the impact that spelling variation can have on frequency counts.

5 Results: the role of space and motion in the OE conceptualization of time

OE vocabulary shows that time, space and motion were closely linked. A large number of words denoted both time and space or motion-related concepts. Following the MIP, we have been able to determine that 7.7 and 4.3 percent of the words recorded in the Thesaurus of Old English under the categories space and motion, respectively, underwent metaphoric transfer and were also used to refer to time (see appendixes 1 and 2 for a list of words that used to have spatial/motion-related senses and also displayed temporal meanings). This implies that 13.2 percent (163 out of 1279) of OE time words were metaphorically related to terms that also denoted spatial and motion concepts and attests to the significance of space and motion in the conceptualization and description of time in Old English, which exhibited a circular and linear conceptualization, resorted to the vertical and sagittal axes to sequence events in time and used allocentric (i.e. a time construal anchored in an entity distinct from the ego) and egocentric frames of reference (see table 1 for an overview of the spatialization of time in Old English which will be described in detail below).

Table 1. Metaphorical construals of time in Old English

a Events perceived as statically ordered.

b Events perceived as in motion.

5.1 The circular conceptualization of time: cyclical metaphorical construals of time

In early medieval England, time was essentially associated with natural cycles and the holidays of the liturgical year. The few calendars which were used were connected to psalters and martyrologies and provided information on cyclical religious commemorations. The OE poem Menologium, with its circular structure and the integration the feasts of the saints into the natural year cycle, exemplifies this circular conception of time, which is also reflected in OE vocabulary. The adjective dæg-ryne (‘day-orbit/course/run’), which meant ‘daily, of a day’, or the noun hring, which in its non-temporal sense meant ‘ring, circle, circuit, cycle, globe, orbit’ and in its temporal sense referred to the ‘cycle of a year’ (as in (1)) are obvious examples of it. These words along with others such as circul ‘cycle’, which was borrowed from Latin and used as a technical term for computation in astronomical and religious contexts (2), show a circular conceptualization of days and years. Other OE terms such as tācn-circul ‘an indiction, a 15-year cycle’, used in dating both in Rome and England, also reflect a circular understanding of other time intervals.

Moreover, the OE lexicon provides proof that the notion of time progress was also linguistically encoded by means of terms that evoked a circular path. The noun hwearft, used in astronomical contexts to refer to ‘the circuit, orbit, expanse of the stars’, was also found in combination with time units such as OE winter and gēar ‘year’ to describe the passing of years (3).

5.2 The linear conceptualization of time

This circular view of time coexisted with a linear conceptualization of time that sequenced time units and events along the vertical and sagittal axes.

5.2.1 Vertical metaphorical construals of time

Early English records show that, in the OE period, time was also conceptualized as a vertically oriented line. In this case, an above–below schema served as the basis for the temporal ordering of events, which resulted in the mapping later is higher/up. This spatiotemporal association becomes apparent in expressions where the comparative adverb ufor ‘higher, further up’ is used with the meaning of ‘later’ (4), and the comparative adjective uferra ‘upper, higher' and the preposition onufan ‘upon, beyond’ refer to a point in time that will come ‘later, after’ (5)–(6).

The related verb uferian, which in its literal sense meant ‘to elevate, raise up or make higher’, was also used with the meaning ‘to delay’ (7), evoking the idea that the act of delaying an event implies a form of metaphorical upward motion.

Finally, ofer, whose original sense was probably ‘near’, with reference to things lying above one another (Skeat Reference Skeat1884), was used as a preposition (8) or prefix (e.g. ofer-nōn ‘after-noon’) to refer to a point in time later than that indicated by the accompanying time unit.

The alignment of time along the vertical axis in Old English is consistent with the fact that, in perceptual terms, points situated further away appear to be higher than those near to us and also with the hypothesis that in early Germanic culture time was seen as cumulative and open-ended with the past constantly increasing and pulling more and more time and events into itself (Bauschatz Reference Bauschatz1982). In this context, the events that take place later or are put off would occupy a higher position in metaphorical terms.

Time and vertical space also conflate in metonymic temporal expressions where the position of the sun in the sky relative to the ego at a certain time of the day stands for the time itself. For example, noon is the time of the day when the sun is highest in the sky, which seems to motivate the temporal meaning of the adjective hēah ‘high’, which in Old English also meant ‘noon, mid-day’.

Similarly, the expression (ge)loten dæg ‘afternoon’, formed by the past participle of the verb lūtan ‘to bend, stoop’ and the noun dæg ‘day’, also seems to be metonymically motivated by the association of the sun's descent from its zenith with the time when it takes place, the afternoon. This might also explain why OE first (also fyrst) developed a temporal sense. First had a spatial meaning which was feminine and referred to ‘the top, the roof, the inner roof (ceiling) or the beam which supported the roof or the ceiling’. It also had a temporal meaning which was masculine and referred to a period or a space of time (9) (Jankowsky Reference Jankowsky, Dick and Jankowsky1982; Kopár Reference Kopár, Hall, Timofeeva, Kiricsi and Fox2010). The link between these two notions is assumed to be based on the use of the beam of the roof as an instrument to measure the sun's movement (Jankowsky Reference Jankowsky, Dick and Jankowsky1982), a practice consistent with the use of daymarks (i.e. geographical features such as mountains or hills) for time keeping from ancient times (Nilsson Reference Nilsson1920: 21).

5.2.2 Sagittal metaphorical construals of time

According to Bartolotta (Reference Bartolotta2018), the different positions of the sun during the day also motivated the development in ancient Indo-European languages of time-based metaphorical mappings that presented earlier (and past) events as in front of later events and later (and future) events as behind earlier ones. This spatiotemporal interplay is also present in Old English where the sagittal (front–back) axis was used to convey sequence time concepts (i.e. time-based) and deictic time concepts (i.e. ego-based).

5.2.2.1 Time-based construals of time

OE vocabulary indicates that sagittal (front–back) language was employed to describe sequential relationships among events so that earlier times were conceptualized as lying ahead of later times and that, as is also true of Modern English, time-based metaphors did not entail a canonical observer or a compulsory specification of now. The use of directional expressions such as fōre ‘before in place/ position’, befōran ‘in front, before, ahead’ or ætforan ‘preceding, in front of, at the head of’ as time markers illustrates this metaphorical pattern. In their spatial senses these terms were used to mark position and direction. In their temporal senses they were found in sequential expressions referring to a date or event that occurred ‘before, prior to, earlier than other’ (10)–(11).

Spatial adverbs/prepositions such as æfter or bæftan/beæftan, whose meaning was ‘behind’, were also used to describe a time or event that happened ‘afterwards, subsequently, at a later time’ (12).

Derived forms such as fōran-dæg ‘the early part of the day’ and fōran-niht ‘the early part of the night’ as well as temporal expressions, in which fōre-weard ‘situated in front’ and æfte-weard ‘behind, in the rear’ designated the earliest and latter parts of a period of time, respectively (13)–(14), also illustrate this front-before, back-after metaphorical association. In this particular case, a time unit is seen as made of various segments the earliest of which is in front and the latter behind.

The motion uses of directional expressions, in which an entity or individual was described as going first or later in the order of motion, might explain the development of dynamic time expressions where events are not perceived as statically ordered in succession with respect to each other but as in motion.

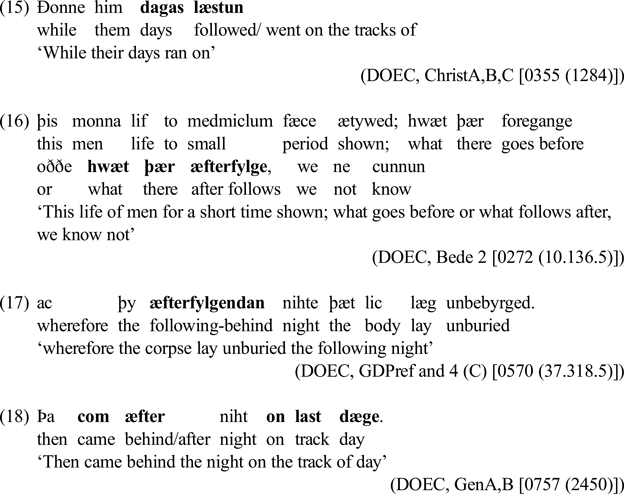

This dynamic time-based construction of time is present in examples where verbs such as lǣstan ‘follow, accompany’ or æfter-fylgan ‘to follow, to go or come behind’ and nouns such as lāst ‘step, footstep, track, trace’ were used to represent sequential time relations where times were construed as moving. Lǣstan denoted temporal continuity and appeared in combination with complements that specified a period of time (15). Fylgan and æfter-fylgan were used as verbs or participial adjectives with the meaning ‘to follow in time’ (16)–(17) while lāst appeared in the construction on lāst(e) with the meaning ‘behind, after, in pursuit of’, denoting temporal succession (18). This pattern suggests that the spatial sense of ‘follow’ was metaphorically extended to the domain of time, giving way to the temporal sense of ‘follow’, a metaphorical pattern that is not exclusive to English (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997: 64).

The metaphorical extension of the spatial sense of ‘follow’ to the domain of time would also explain the development of the derivative term lastweard ‘one who keeps in the steps of another, pursuer’, which was also used to refer to the descendants, heirs or successors to another person (19).

Data also show that the vertical and the sagittal axes entwined in some time expressions. In on foreweardne sumor and eft on ufeweardne hærfest ‘in the early part of the summer and again in the latter part of autumn’ (DOEC, ChronC (O'Brien O'Keeffe) [0479 (914.2.1)]), for example, the adjectives foreweardne ‘forward, early’ and ufeweardne ‘the upper part of something, latter part of a time’ call for the sagittal and the vertical axes, respectively. This situation does not seem to be an exception given that data show that both axes were flexibly engaged to describe the temporal order of events.

All these expressions show that, in Old English, temporal sequences were assigned directionality and that times and events could be treated as locations but also as moving entities so that a temporally later unit was seen as being or going behind an earlier one. In these constructions only the sequence of time was in focus, regardless of whether it was in the past, present or future. However, OE data show that an ego-based conceptualization of time also existed.

5.2.2.2 Ego-based construals of time

The use of terms also related to the sagittal axis, such as forþ ‘forwards, onwards, hence, thence, henceforth, further’, heonan forþ ‘from here forth’ or forþweard ‘forward’, to refer to time introduced a deictic construal of time that took the experiencer's now as a point of reference (20)–(21).

When time was spatialized relative to an ego's now, it could be presented as a moving entity approaching and passing by from the future (ahead of the observer) to the past (behind the observer) or as a static timeline. The time-moving variant of the ego-based metaphor manifests itself in time expressions that resort to motion verbs such as forþ(ge)faran ‘go forth, depart’, forþgān ‘go forth, advance’, forþ-gewītan ‘to go forth, proceed, go by’, gewītan ‘go away, depart’ or bi-lēoran ‘pass by’ to describe the march of time (22).Footnote 7 A state of permanence, on the contrary, rested on the idea of absence of motion. This notion is illustrated by the adverb ungewītendlīce ‘permanently without passing away’, which was formed by derivation from un ‘not’ + gewītan ‘to go away, to leave, to depart’.

In this context, past times and events were presented as gone, passed away (23). Memory verbs such as gehwierfan ‘to bring, to call to mind’, which derives from hwierfan ‘to return’ and describes the act of remembering as the mental capacity to move backward in time to bring to the mind events or people from the past, also provide evidence that the notion of past was conceptualized not only as gone but also as being behind the ego.

Future events, however, were described as coming towards, approaching the ego. This becomes apparent in examples where the noun cyme ‘coming’ (24) and the verb cuman ‘come, approach, arrive, move towards’ (25) are used to refer to future times or events. Further evidence for this conceptualization of future is seen in the adjective tō-weard, which was formed by the preposition tō ‘in the direction of’ and the suffix -weard ‘turned toward’. In its spatial sense, this adjective, like other adjectives in -weard, could denote direction of movement or relative position (OED). In the former case, it was used with the meaning ‘coming towards a place, approaching’. In the latter, it described the position of an entity as ‘facing’, with the face towards a person. In its temporal sense it meant ‘future, that is to come, approaching’ (26). Given that spatially it implied that the entity it modified was approaching or facing another entity, when referring to future events, the use of this adjective might imply that those events were conceptualized not only as approaching a stationary ego but also as facing it. This conceptual transfer from space to time might be plausible, if we take into account that when time is conceptualized as moving, time units are assumed to have an intrinsic front–back orientation (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997: 59).

As pointed out in section 3, previous research has argued that the concept of future was a loan concept to OE speakers, who borrowed it after conversion. OE glosses to Latin texts and examples such as (27), which is the OE translation of the sentence beata quoque agmina caelestium spirituum, preterita, pręsentia, futura mala pellite, show that the Latin term futurus and its derivative forms were translated into OE spatial terms, specifically the word tō-weard.

This indicates that even if the notion of future, understood as the end of time, was a cultural borrowing, OE translations were not a mechanical rendering of Latin texts. OE authors ‘germanized’ the concept by relying on the spatio-directional term tō-weard ‘facing and approaching’ to introduce it to their audience.

Finally, OE records also show evidence for the ego-moving variant of the metaphor in examples such as (28), in which hours become the path that takes the ego to death, and (29) where the verb ge-nēalǣcan ‘to move nearer to an object, get near’ is used to refer to the time of death.

6 Discussion and conclusion

To summarize, the analysis above indicates that, in Old English, time was in part structured metaphorically by circular and linear spatial relations that flexibly engaged the vertical and sagittal axes and that allowed for an allocentric and egocentric perspective in the ordering of events. The circular conceptualization of time that OE vocabulary shows seems to have been grounded in the observation of repetitive patterns in nature and the belief that time and events repeated in cycles, a worldview common to many pre-Christian cultures (Urbańczyk Reference Urbańczyk and Carver2003). The linear understanding of time that OE data also show may be considered as a reflection of how the Christian doctrine contributed to shaping people's perception of history and time. The adoption of Christianity and its eschatological view of time as irreversible, linear, finite and bounded to the Creation and the Final Judgment Day, respectively, are argued to have played a significant role in the development and/or consolidation of the linear conceptualization of time that is dominant in western cultures (Lee & Liebenau Reference Lee and Liebenau2000). This along with the shift from nature-based time-reckoning methods to time measuring modes based on the use of the clock and the calendar might explain why the cyclical dimension of time gave way to a predominantly linear conceptualization of time. Although the cyclical time metaphor has not died out, it has decreased in salience to the extent that, in Modern English, it is rather exceptional. It only survives in a handful of idiomatic expressions (e.g. round the clock, year-round, the turn of the century or to turn x years old) that describe time intervals ranging from centuries to days (Radden Reference Günter, Baumgarten, Böttger, Motz and Probst2004). As stated by Trim (Reference Trim2007: 220–3), cultural changes influence the life span of metaphors. Source domains may fluctuate over time in response to cultural variation, which influences the use and salience of metaphors leading to their obsolescence in some cases.

Construing time as a linear path necessarily involves orientation in space. In this respect, Old English shows that time could be conceptualized as a vertically or horizontally oriented line. In the former case, later times were conceptualized as being above earlier times (later is higher/up). Data suggest that this metaphor was asymmetrically used since the mapping earlier is lower/down is not attested in the TOE, probably because the metaphor earlier is in front occupied this space. The vertical axis also participated in metonymic expressions of time where the position of the sun or its reflection were used as daymarks. In Modern English, as in many other European languages, the vertical axis is also currently constrained to marginal uses (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997: 22).

As far as the use of the sagittal axis is concerned, OE vocabulary indicates that two construals were possible: (a) a time-based, non-deictic construal and (b) an ego-based, deictic one, which had two variants: the time-moving and the ego-moving metaphors, considered a figure-ground reversal of each other (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999: 128–30).

The time-based construal has been found to have a long tradition in ancient Indo-European languages, being connected to spatiotemporal mappings derived from the position of the sun during the day (Bartolotta Reference Bartolotta2018). OE data indicate that this construal and particularly the concepts earlier and later, as also reported by Yang (Reference Yang2020: 36), were tightly connected to the spatial notions of before and after. Our analysis also shows that the front/back axis was mapped onto the time line with static and dynamic variants where the notion of spatial ‘follow’ was conceptually transferred to that of temporal ‘follow’. In this context, not only the concepts before and after played a significant role but other dynamic spatial concepts such those represented by the verb fylgan ‘to go behind, follow’ and other derived forms of this base also contributed to the expression of temporal sequences.

In the case of the ego-based metaphor, there is evidence that past and future were seen as passing by and approaching, respectively, and that the Christian notion of future (i.e. future as end of time) was conceptualized and described in spatial terms in Old English. In this sense, in line with Yang (Reference Yang2020: 53), data show that the expression of the notion of future or time to come heavily depended on words derived from the prefix forþ- ‘forth’. Our results add to this finding by showing that forth-related terms added a deictic perspective to the expression of future and that the use of alternative words such as cyme ‘coming’ or cuman ‘come, approach, arrive, move towards’ to convey the concept of future indicates that it was not only conceptualized as a form of forward movement but also as an approaching entity. Finally, memory-related verbs such as the OE verb gehwierfan ‘to bring, to call to mind’, which describe the act of remembering an event as a return back to the past, support the claim that the past was seen as gone and behind. In short, the analysis of OE vocabulary that has been sketched out here attests to the intersection of the temporal and spatial dimensions of the OE conceptual system in the understanding and expression of time concepts.

The present article adds to previous research on the metaphorical conceptualization of time (Kopár Reference Kopár, Hall, Timofeeva, Kiricsi and Fox2010; Yang Reference Yang2020) by providing a comprehensive analysis of the spatiotemporal mappings that emerge from the lexical overlaps identified in the domains of space/motion and time in Old English with reference to the circular, vertical and sagittal axes as well as of the deictic, static and dynamic variants that they exhibit. Moreover, this study frames results within a wider perspective, showing that, on the basis of Modern English research on time conceptualization, the relative salience of the spatial metaphors used in Old English has changed. The use of the linear axis has increased in contrast to the circular axis, which has receded. This can be explained by social and cultural factors linked to the use of new time reckoning methods and the influence of Christian traditions. In conclusion, the time metaphors recorded in the earliest documented periods of the history of English give proof of a persistent link between time, space and motion and suggest that a baseline conceptualization of time resting on spatial relations has existed through time, surviving to the present day and reflecting the subtle interplay of language, cognition and culture.

While this study offers a comprehensive analysis and illustration of spatiotemporal relations in OE vocabulary, it is not without limitations. Given the large number of lexical units that have been analyzed, a quantitative analysis of their frequency and genre distribution goes beyond the scope of this article. Future research should approach this aspect as well as the analysis of other potential metaphorical conceptualizations of time in the Old English period.

Appendix 1. Motion–time lexical overlaps

Appendix 2. Space–time lexical overlaps