1 Introduction

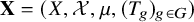

Let

![]() $(G,+)$

be a countable discrete abelian group. A probability measure-preserving G-system, or simply G-system for short, is a quadruple

$(G,+)$

be a countable discrete abelian group. A probability measure-preserving G-system, or simply G-system for short, is a quadruple

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

, where

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

, where

![]() $(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

is a standard Borel probability space (that is, up to isomorphism of measure spaces, X is a compact metric space,

$(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

is a standard Borel probability space (that is, up to isomorphism of measure spaces, X is a compact metric space,

![]() $\mathcal {X}$

is the Borel

$\mathcal {X}$

is the Borel

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra and

$\sigma $

-algebra and

![]() $\mu $

is a regular Borel probability measure) and

$\mu $

is a regular Borel probability measure) and

![]() $T_g :X \to X$

,

$T_g :X \to X$

,

![]() $g \in G$

, are measure-preserving transformations, such that

$g \in G$

, are measure-preserving transformations, such that

![]() $T_{g+h}=T_g\circ T_h$

for every

$T_{g+h}=T_g\circ T_h$

for every

![]() $g,h\in G$

and

$g,h\in G$

and

![]() $T_0=Id$

. The transformation

$T_0=Id$

. The transformation

![]() $T_g:X \to X$

gives rise to a unitary operator on

$T_g:X \to X$

gives rise to a unitary operator on

![]() $L^2(\mu )$

, which we also denote by

$L^2(\mu )$

, which we also denote by

![]() $T_g$

, given by the formula

$T_g$

, given by the formula

![]() $T_g f(x) = f(T_g x)$

. We say that a G-system is ergodic if the only measurable

$T_g f(x) = f(T_g x)$

. We say that a G-system is ergodic if the only measurable

![]() $(T_g)_{g\in G}$

-invariant functions are the constant functions.

$(T_g)_{g\in G}$

-invariant functions are the constant functions.

1.1 Khintchine-type recurrence and the large intersections property

The starting point for the study of recurrence in ergodic theory is the Poincaré recurrence theorem, which states that, for any measure-preserving system

![]() $\left(X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , T \right)$

and any set

$\left(X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , T \right)$

and any set

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

![]() $\mu (A)> 0$

, there exists

$\mu (A)> 0$

, there exists

![]() $n \in \mathbb N$

, such that

$n \in \mathbb N$

, such that

![]() $\mu (A \cap T^{-n}A)> 0$

.

$\mu (A \cap T^{-n}A)> 0$

.

Khintchine’s recurrence theorem strengthens and enhances Poincaré’s recurrence theorem by improving on the size of the intersections and the size of the set of return times.

Theorem 1.1 (Khintchine’s recurrence theorem [Reference Khintchine24])

For any measure-preserving system

![]() $\left(X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , T \right)$

, any

$\left(X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , T \right)$

, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

![]() $\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

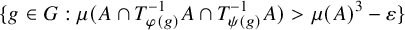

has bounded gaps.

Khintchine’s recurrence theorem easily extends to general semigroups, where the appropriate counterpart of ‘bounded gaps’ is the notion of syndeticity. In this paper, we deal with recurrence in countable discrete abelian groups. A subset A of a countable discrete abelian group G is said to be syndetic if there exists a finite set

![]() $F\subseteq G$

, such that

$F\subseteq G$

, such that

![]() $A+F = \{a+f : a\in A, f\in F\} = G$

.

$A+F = \{a+f : a\in A, f\in F\} = G$

.

It is natural to ask if recurrence theorems other than Poincaré’s recurrence theorem also have Khintchine-type enhancements. For instance, it follows from the IP Szemerédi theorem of Furstenberg and Katznelson [Reference Furstenberg and Katznelson20] and also from [Reference Austin3, Theorem B] that, for any abelian group G, any

![]() $k \in \mathbb N$

and any family of homomorphisms

$k \in \mathbb N$

and any family of homomorphisms

![]() $\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k : G \to G$

, the following holds: if

$\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k : G \to G$

, the following holds: if

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

is a G-system and

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

is a G-system and

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

has

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

has

![]() $\mu (A)> 0$

, then the set

$\mu (A)> 0$

, then the set

is syndetic.Footnote 1 With the goal of Khintchine-type enhancements in mind, this motivates the following definition:

Definition 1.2. A family of homomorphisms

![]() $\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k : G \to G$

has the large intersections property if the following holds: for any ergodic G-system

$\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k : G \to G$

has the large intersections property if the following holds: for any ergodic G-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

![]() $\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

The large intersections property is closely related to the phenomenon of popular differences in combinatorics (see, e.g. [Reference Ackelsberg and Bergelson1, Reference Berger11, Reference Berger, Sah, Sawhney and Tidor12, Reference Mandache25, Reference Sah, Sawhney and Zhao26]).

Determining which families of homomorphisms have the large intersections property is a challenging problem with many surprising features. In the case

![]() $G = {\mathbb Z}$

and

$G = {\mathbb Z}$

and

![]() $\varphi _i(n) = in$

, the problem was resolved in [Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8].

$\varphi _i(n) = in$

, the problem was resolved in [Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8].

Theorem 1.3 ([Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8], Theorems 1.2 and 1.3)

The family

![]() $\{n, 2n, \dots , kn\}$

has the large intersections property in

$\{n, 2n, \dots , kn\}$

has the large intersections property in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}$

if and only if

${\mathbb Z}$

if and only if

![]() $k \le 3$

.

$k \le 3$

.

Later work of Frantzikinakis [Reference Frantzikinakis18] and of Donoso et al. [Reference Donoso, Le, Moreira and Sun15] generalised this picture for arbitrary homomorphisms

![]() ${\mathbb Z} \to {\mathbb Z}$

, which take the form

${\mathbb Z} \to {\mathbb Z}$

, which take the form

![]() $n \mapsto an$

for some

$n \mapsto an$

for some

![]() $a \in {\mathbb Z}$

.

$a \in {\mathbb Z}$

.

Theorem 1.4 ([Reference Frantzikinakis18], special case of Theorem C; [Reference Donoso, Le, Moreira and Sun15], Theorem 1.5)

-

1. For any

$a, b \in {{\mathbb Z}}$

, the families

$a, b \in {{\mathbb Z}}$

, the families

$\{an,bn\}$

and

$\{an,bn\}$

and

$\{an, bn, (a+b)n\}$

have the large intersections property (in

$\{an, bn, (a+b)n\}$

have the large intersections property (in

${\mathbb Z}$

).

${\mathbb Z}$

). -

2. For any

$k \ge 4$

and any distinct and nonzero integers

$k \ge 4$

and any distinct and nonzero integers

$a_1, \dots , a_k \in {\mathbb Z}$

, the family

$a_1, \dots , a_k \in {\mathbb Z}$

, the family

$\{a_1n, \dots , a_kn\}$

does not have the large intersections property (in

$\{a_1n, \dots , a_kn\}$

does not have the large intersections property (in

${\mathbb Z}$

).

${\mathbb Z}$

).

Remark 1.5. Finitary combinatorial work of [Reference Sah, Sawhney and Zhao26, Theorem 1.6] suggests that the family

![]() $\{a_1n,a_2n,a_3n\}$

has the large intersections property if and only if

$\{a_1n,a_2n,a_3n\}$

has the large intersections property if and only if

![]() $a_i+a_j=a_k$

for some permutation

$a_i+a_j=a_k$

for some permutation

![]() $\{i,j,k\}$

of

$\{i,j,k\}$

of

![]() $\{1,2,3\}$

.

$\{1,2,3\}$

.

In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10], Khintchine-type recurrence results are established in the infinitely generated torsion groups

![]() $G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

Theorem 1.6 ([Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10], Theorems 1.12 and 1.13)

-

1. Fix a prime

$p> 2$

. If

$p> 2$

. If

$c_1, c_2 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero, then

$c_1, c_2 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero, then

$\{c_1g,c_2g\}$

has the large intersections property in

$\{c_1g,c_2g\}$

has the large intersections property in

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

. -

2. Fix a prime

$p> 3$

. If

$p> 3$

. If

$c_1, c_2 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero and

$c_1, c_2 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero and

$c_1 + c_2 \ne 0$

, then

$c_1 + c_2 \ne 0$

, then

$\{c_1g, c_2g, (c_1+c_2)g\}$

has the large intersections property in

$\{c_1g, c_2g, (c_1+c_2)g\}$

has the large intersections property in

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

Remark 1.7. It is conjectured in [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10, Conjecture 1.14] that, if

![]() $c_1, c_2, c_3 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero and

$c_1, c_2, c_3 \in {\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}$

are distinct and nonzero and

![]() $c_i+c_j \ne c_k$

for every permutation

$c_i+c_j \ne c_k$

for every permutation

![]() $\{i,j,k\}$

of

$\{i,j,k\}$

of

![]() $\{1,2,3\}$

, then

$\{1,2,3\}$

, then

![]() $\{c_1g, c_2g, c_3g\}$

does not have the large intersections property in

$\{c_1g, c_2g, c_3g\}$

does not have the large intersections property in

![]() $G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}/p{\mathbb Z}}$

.

Khintchine-type recurrence in general abelian groups was addressed in [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2] and [Reference Shalom27]. For 3-point linear configurations, the following was shown in [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2]:

Theorem 1.8 ([Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2], Theorem 1.10)

Let G be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

![]() $\varphi ,\psi :G \to G$

be homomorphisms. If all three of the subgroups

$\varphi ,\psi :G \to G$

be homomorphisms. If all three of the subgroups

![]() $\varphi (G)$

,

$\varphi (G)$

,

![]() $\psi (G)$

and

$\psi (G)$

and

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

have finite index in G, then

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

have finite index in G, then

![]() $\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

has the large intersections property.

$\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

has the large intersections property.

Remark 1.9. Earlier work of Chu demonstrates that at least some finite index condition is necessary for large intersections. Namely, it follows from [Reference Chu13, Theorem 1.2] that the pair

![]() $\{(n,0), (0,n)\}$

, does not have the large intersections property in

$\{(n,0), (0,n)\}$

, does not have the large intersections property in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

(see [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Example 10.2]). While we do not pursue optimal lower bounds for families lacking the large intersections property in this paper, Chu also showed that, for the pair

${\mathbb Z}^2$

(see [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Example 10.2]). While we do not pursue optimal lower bounds for families lacking the large intersections property in this paper, Chu also showed that, for the pair

![]() $\{(n,0), (0,n)\}$

, the optimal lower bound is still polynomially large. In particular,

$\{(n,0), (0,n)\}$

, the optimal lower bound is still polynomially large. In particular,

![]() $\mu \left( A \cap T_{(n,0)}^{-1}A \cap T_{(0,n)}^{-1}A \right)> \mu (A)^4 - \varepsilon $

for syndetically many n (see [Reference Chu13, Theorem 1.1]).

$\mu \left( A \cap T_{(n,0)}^{-1}A \cap T_{(0,n)}^{-1}A \right)> \mu (A)^4 - \varepsilon $

for syndetically many n (see [Reference Chu13, Theorem 1.1]).

For more restricted 4-point configurations, the following result was shown in [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2] and independently in [Reference Shalom27]:

Theorem 1.10 ([Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2], Theorem 1.11; [Reference Shalom27], Theorem 1.3)

Let G be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

![]() $a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

be distinct, nonzero integers, such that all four of the subgroups

$a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

be distinct, nonzero integers, such that all four of the subgroups

![]() $aG$

,

$aG$

,

![]() $bG$

,

$bG$

,

![]() $(a+b)G$

and

$(a+b)G$

and

![]() $(b-a)G$

have finite index in G. Then

$(b-a)G$

have finite index in G. Then

![]() $\{ag, bg, (a+b)g\}$

has the large intersections property.

$\{ag, bg, (a+b)g\}$

has the large intersections property.

1.2 Main results

In this paper, we refine the understanding of Khintchine-type recurrence for 3-point configurations in abelian groups and make substantial progress towards characterising the pairs of homomorphisms

![]() $\varphi , \psi : G \to G$

that have the large intersections property.

$\varphi , \psi : G \to G$

that have the large intersections property.

Our first result shows that the large intersections property holds for any pair of homomorphisms

![]() $\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

so long as at least two of the three subgroups in Theorem 1.8 have finite index in G. In particular, this shows that [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Conjecture 10.1] is false.

$\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

so long as at least two of the three subgroups in Theorem 1.8 have finite index in G. In particular, this shows that [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Conjecture 10.1] is false.

Theorem 1.11. Let G be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

![]() $\varphi , \psi : G \to G$

be homomorphisms, such that at least two of the three subgroups

$\varphi , \psi : G \to G$

be homomorphisms, such that at least two of the three subgroups

![]() $\varphi (G)$

,

$\varphi (G)$

,

![]() $\psi (G)$

and

$\psi (G)$

and

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

have finite index in G. Then for any ergodic G-system

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

have finite index in G. Then for any ergodic G-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, the set

$\varepsilon>0$

, the set

is syndetic.

As mentioned above (see Remark 1.9), the work of Chu [Reference Chu13] provides a counterexample to the large intersections property when all three subgroups

![]() $\varphi (G)$

,

$\varphi (G)$

,

![]() $\psi (G)$

and

$\psi (G)$

and

![]() $(\psi - \varphi )(G)$

have infinite index in G. In this paper, we give additional counterexamples for the group

$(\psi - \varphi )(G)$

have infinite index in G. In this paper, we give additional counterexamples for the group

![]() $G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}}$

with homomorphisms

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}}$

with homomorphisms

![]() $g \mapsto ag$

and

$g \mapsto ag$

and

![]() $g \mapsto bg$

for some

$g \mapsto bg$

for some

![]() $a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

(see Theorem 1.14 below). A natural question to ask, then, is what happens when only one of the subgroups

$a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

(see Theorem 1.14 below). A natural question to ask, then, is what happens when only one of the subgroups

![]() $\varphi (G)$

,

$\varphi (G)$

,

![]() $\psi (G)$

or

$\psi (G)$

or

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index. Namely:

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index. Namely:

Question 1.12. Let G be a countable discrete abelian group, and let

![]() $\varphi :G\rightarrow G$

,

$\varphi :G\rightarrow G$

,

![]() $\psi :G\rightarrow G$

be homomorphisms, such that at least one of the subgroups

$\psi :G\rightarrow G$

be homomorphisms, such that at least one of the subgroups

![]() $\varphi (G)$

,

$\varphi (G)$

,

![]() $\psi (G)$

or

$\psi (G)$

or

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index in G. Is it true that, for any ergodic G-system

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index in G. Is it true that, for any ergodic G-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

![]() $A\in \mathcal {X}$

, and any

$A\in \mathcal {X}$

, and any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, the set

$\varepsilon>0$

, the set

is syndetic?

Note that, by symmetry, it is enough to provide an answer to Question 1.12 under the assumption that

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index. Indeed, suppose

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index. Indeed, suppose

![]() $\psi (G)$

has finite index in G. Then, since

$\psi (G)$

has finite index in G. Then, since

![]() $(T_g)_{g \in G}$

is a measure-preserving action, we have the identity

$(T_g)_{g \in G}$

is a measure-preserving action, we have the identity

Hence, the pair

![]() $\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

has the large intersections property if and only if

$\{\varphi ,\psi \}$

has the large intersections property if and only if

![]() $\left\{\widetilde {\varphi }, \widetilde {\psi }\right\}$

has the large intersections property, where

$\left\{\widetilde {\varphi }, \widetilde {\psi }\right\}$

has the large intersections property, where

![]() $\widetilde {\varphi } = - \varphi $

and

$\widetilde {\varphi } = - \varphi $

and

![]() $\widetilde {\psi } = \psi - \varphi $

. Moreover, we have

$\widetilde {\psi } = \psi - \varphi $

. Moreover, we have

![]() $(\widetilde {\psi } - \widetilde {\varphi })(G) = \psi (G)$

, which is of finite index. A similar argument applies when

$(\widetilde {\psi } - \widetilde {\varphi })(G) = \psi (G)$

, which is of finite index. A similar argument applies when

![]() $\varphi (G)$

has finite index.

$\varphi (G)$

has finite index.

When

![]() $G = {\mathbb Z}^2$

, we can use additional tools from linear algebra to classify all pairs of homomorphisms

$G = {\mathbb Z}^2$

, we can use additional tools from linear algebra to classify all pairs of homomorphisms

![]() $\varphi $

and

$\varphi $

and

![]() $\psi $

, which allows us to answer Question 1.12 affirmatively in this setting. In fact, we can give a precise description of the optimal size of intersections for all 3-point configurations in

$\psi $

, which allows us to answer Question 1.12 affirmatively in this setting. In fact, we can give a precise description of the optimal size of intersections for all 3-point configurations in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

(see Subsection 1.4 below). However, our results rely heavily on properties of

${\mathbb Z}^2$

(see Subsection 1.4 below). However, our results rely heavily on properties of

![]() $2\times 2$

matrices, and it appears that the full generality of Question 1.12 for general abelian groups and general homomoprhisms is out of reach without developing new techniques.

$2\times 2$

matrices, and it appears that the full generality of Question 1.12 for general abelian groups and general homomoprhisms is out of reach without developing new techniques.

On the other hand, in the special case

![]() $\varphi (g) = ag$

and

$\varphi (g) = ag$

and

![]() $\psi (g) = bg$

for

$\psi (g) = bg$

for

![]() $a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

, we answer Question 1.12 affirmatively:

$a, b \in {\mathbb Z}$

, we answer Question 1.12 affirmatively:

Theorem 1.13. Let G be a countable discrete abelian group. Let

![]() $a,b\in \mathbb {Z}$

be integers, such that

$a,b\in \mathbb {Z}$

be integers, such that

![]() $(b-a)G$

has finite index in G. Then for any ergodic G-system

$(b-a)G$

has finite index in G. Then for any ergodic G-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

, any

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

and any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, the set

$\varepsilon>0$

, the set

is syndetic.

We also show that the assumption that

![]() $(b-a)G$

has finite index in G is necessary. To see this, we prove the following result:

$(b-a)G$

has finite index in G is necessary. To see this, we prove the following result:

Theorem 1.14. Let

![]() $G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}}$

. Let

$G = \bigoplus _{n=1}^{\infty }{{\mathbb Z}}$

. Let

![]() $l \in \mathbb N$

. There exists a number

$l \in \mathbb N$

. There exists a number

![]() $P = P(l)$

, such that, for any

$P = P(l)$

, such that, for any

![]() $a, b \in \mathbb N$

with

$a, b \in \mathbb N$

with

![]() $p \mid \gcd (a,b)$

for some prime

$p \mid \gcd (a,b)$

for some prime

![]() $p \ge P$

, there is an ergodic G-system

$p \ge P$

, there is an ergodic G-system

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

and a set

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

and a set

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

![]() $\mu (A)> 0$

, such that

$\mu (A)> 0$

, such that

for every

![]() $g\ne 0$

.

$g\ne 0$

.

Question 1.15. Can p in the statement of Theorem 1.14 be replaced by any natural number?

1.3 Applications to geometric progressions and other multiplicative patterns

One particularly interesting corollary of Theorem 1.13 is a multiplicative version of the following large intersection theorem in [Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8]:

Theorem 1.16 ([Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8], Corollary 1.5)

Let

![]() $E \subseteq {\mathbb Z}$

be a set of positive upper Banach density

$E \subseteq {\mathbb Z}$

be a set of positive upper Banach density

Then, for any

![]() $\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

$\varepsilon> 0$

, the set

is syndetic.

Consider the group

![]() $G=(\mathbb {Q}_{>0},\cdot )$

. This is a multiplicative counterpart of

$G=(\mathbb {Q}_{>0},\cdot )$

. This is a multiplicative counterpart of

![]() $(\mathbb {Z},+)$

. In the group

$(\mathbb {Z},+)$

. In the group

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

, the upper Banach density of a set

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

, the upper Banach density of a set

![]() $E \subseteq \mathbb Q_{>0}$

is given by

$E \subseteq \mathbb Q_{>0}$

is given by

where the supremum is taken over all Følner sequences

![]() $\Phi = (\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

in

$\Phi = (\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

in

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

. An instructive class of examples of Følner sequences in

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

. An instructive class of examples of Følner sequences in

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

is given by sequences of the form

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

is given by sequences of the form

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi_N = \left\{ b_N \prod_{i=1}^N{q_i^{r_i}} : -N \le r_i \le N \right\}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi_N = \left\{ b_N \prod_{i=1}^N{q_i^{r_i}} : -N \le r_i \le N \right\}, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $(q_n)_{n \in \mathbb N}$

is a sequence of generators of

$(q_n)_{n \in \mathbb N}$

is a sequence of generators of

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

and

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

and

![]() $(b_N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is any sequence in

$(b_N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is any sequence in

![]() $\mathbb Q_{>0}$

. The subscript on

$\mathbb Q_{>0}$

. The subscript on

![]() $d^*_{\text {mult}}$

is to emphasise that this density is with respect to the multiplicative structure on

$d^*_{\text {mult}}$

is to emphasise that this density is with respect to the multiplicative structure on

![]() $\mathbb Q_{>0}$

rather than its additive structure. Using an ergodic version of the Furstenberg correspondence principle (see [Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues6, Theorem 2.8]), we deduce the following result as an immediate consequence of Theorem 1.13:

$\mathbb Q_{>0}$

rather than its additive structure. Using an ergodic version of the Furstenberg correspondence principle (see [Reference Bergelson and Ferré Moragues6, Theorem 2.8]), we deduce the following result as an immediate consequence of Theorem 1.13:

Theorem 1.17. Let

![]() $E\subseteq \mathbb {Q}_{>0}$

be a set of positive multiplicative upper Banach density

$E\subseteq \mathbb {Q}_{>0}$

be a set of positive multiplicative upper Banach density

![]() $d_{\text {mult}}^*(E)> 0$

, and let

$d_{\text {mult}}^*(E)> 0$

, and let

![]() $k\in {\mathbb Z}$

. Then for any

$k\in {\mathbb Z}$

. Then for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, the sets

$\varepsilon>0$

, the sets

and

are syndetic.

Remark 1.18. The special case where

![]() $k=1$

in (2) or

$k=1$

in (2) or

![]() $k = 2$

in (3) is related to the existence of length 3 geometric progressions in sets of positive multiplicative density. Heuristically, if E were a random set, where each positive rational number

$k = 2$

in (3) is related to the existence of length 3 geometric progressions in sets of positive multiplicative density. Heuristically, if E were a random set, where each positive rational number

![]() $q\in \mathbb {Q}_{>0}$

is independently chosen to be inside E with probability

$q\in \mathbb {Q}_{>0}$

is independently chosen to be inside E with probability

![]() $\alpha $

, then the expected number of geometric progressions of length 3 and quotient q would be

$\alpha $

, then the expected number of geometric progressions of length 3 and quotient q would be

![]() $\alpha ^3$

. Now, fix any set E with

$\alpha ^3$

. Now, fix any set E with

![]() $d^*_{mult}(E) = \alpha $

. Choosing

$d^*_{mult}(E) = \alpha $

. Choosing

![]() $\varepsilon $

sufficiently small, our result implies that E contains almost as many geometric progressions with quotient q as a random set with the same density,

$\varepsilon $

sufficiently small, our result implies that E contains almost as many geometric progressions with quotient q as a random set with the same density,

![]() $\alpha $

, for a syndetic set of quotients.

$\alpha $

, for a syndetic set of quotients.

Theorem 1.14 shows that, if n and m share a large prime factor, then

![]() $\{q^n, q^m\}$

does not have the large intersections property in

$\{q^n, q^m\}$

does not have the large intersections property in

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

. What happens in the case that n and m are coprime is an interesting question that we are unable to answer with our current methods:

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

. What happens in the case that n and m are coprime is an interesting question that we are unable to answer with our current methods:

Question 1.19. Suppose

![]() $n, m \in \mathbb N$

are coprime. Does the pair

$n, m \in \mathbb N$

are coprime. Does the pair

![]() $\{q^n, q^m\}$

have the large intersections property in

$\{q^n, q^m\}$

have the large intersections property in

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

?

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

?

Since every

![]() $\mathbb {Z}$

-action can be lifted to a

$\mathbb {Z}$

-action can be lifted to a

![]() $(\mathbb {Q}_{>0}, \cdot )$

-action (indeed,

$(\mathbb {Q}_{>0}, \cdot )$

-action (indeed,

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

is torsion-free, so

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

is torsion-free, so

![]() ${\mathbb Z}$

embeds as a subgroup), we see from Theorem 1.3 above that

${\mathbb Z}$

embeds as a subgroup), we see from Theorem 1.3 above that

![]() $\{q,q^2,\dots , q^k\}$

does not have the large intersections property for

$\{q,q^2,\dots , q^k\}$

does not have the large intersections property for

![]() $k \ge 4$

. However, we can still ask about geometric progressions of length

$k \ge 4$

. However, we can still ask about geometric progressions of length

![]() $4$

.

$4$

.

Question 1.20. Does the triple

![]() $\{q, q^2, q^3\}$

have the large intersections property in

$\{q, q^2, q^3\}$

have the large intersections property in

![]() $(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

?

$(\mathbb Q_{>0}, \cdot )$

?

For a discussion of where our methods come up short for answering Questions 1.19 and 1.20, see Subsection 2.7 below.

1.3.1 Patterns in

$(\mathbb N,\cdot )$

$(\mathbb N,\cdot )$

A notion of upper Banach density can be defined in the semigroup

![]() $(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

by the formula in (1), where the supremum is now taken over Følner sequences in

$(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

by the formula in (1), where the supremum is now taken over Følner sequences in

![]() $(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

. Examples of Følner sequences in

$(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

. Examples of Følner sequences in

![]() $(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

include sequences of the form

$(\mathbb N, \cdot )$

include sequences of the form

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi_N = \left\{ b_N \prod_{i=1}^N{p_i^{r_i}} : 0 \le r_i \le N \right\}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi_N = \left\{ b_N \prod_{i=1}^N{p_i^{r_i}} : 0 \le r_i \le N \right\}, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $(p_n)_{n \in \mathbb N}$

is an enumeration of the prime numbers and

$(p_n)_{n \in \mathbb N}$

is an enumeration of the prime numbers and

![]() $(b_N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is any sequence in

$(b_N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is any sequence in

![]() $\mathbb N$

. In Section 8, we transfer Theorems 1.11 and 1.13 to the setting of cancellative abelian semigroups. As a consequence, we obtain the following result about geometric configurations in the multiplicative integers:

$\mathbb N$

. In Section 8, we transfer Theorems 1.11 and 1.13 to the setting of cancellative abelian semigroups. As a consequence, we obtain the following result about geometric configurations in the multiplicative integers:

Theorem 1.21. Let

![]() $E \subseteq \mathbb N$

be a set of positive multiplicative upper Banach density, and let

$E \subseteq \mathbb N$

be a set of positive multiplicative upper Banach density, and let

![]() $k\in {\mathbb Z}$

. Then for any

$k\in {\mathbb Z}$

. Then for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, the sets

$\varepsilon>0$

, the sets

and

are (multiplicatively) syndetic in

![]() $(\mathbb N,\cdot )$

.

$(\mathbb N,\cdot )$

.

1.4 Applications to patterns in

${\mathbb Z}^2$

${\mathbb Z}^2$

When

![]() $G = {\mathbb Z}^2$

, we are able to give a complete picture of the phenomenon of large intersections for 3-point matrix patterns, that is, patterns of the form

$G = {\mathbb Z}^2$

, we are able to give a complete picture of the phenomenon of large intersections for 3-point matrix patterns, that is, patterns of the form

![]() $\{\vec {x}, \vec {x} + M_1\vec {n}, \vec {x} + M_2\vec {n}\}$

, where

$\{\vec {x}, \vec {x} + M_1\vec {n}, \vec {x} + M_2\vec {n}\}$

, where

![]() $\vec {x}, \vec {n} \in {\mathbb Z}^2$

and

$\vec {x}, \vec {n} \in {\mathbb Z}^2$

and

![]() $M_1, M_2$

are

$M_1, M_2$

are

![]() $2\times 2$

matrices with integer entries (note that any homomorphism

$2\times 2$

matrices with integer entries (note that any homomorphism

![]() $\varphi : {\mathbb Z}^2 \to {\mathbb Z}^2$

can be expressed as a

$\varphi : {\mathbb Z}^2 \to {\mathbb Z}^2$

can be expressed as a

![]() $2\times 2$

matrix with integer entries, so matrix patterns capture all possible configurations in

$2\times 2$

matrix with integer entries, so matrix patterns capture all possible configurations in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

that can be described within the framework of group homomorphisms).

${\mathbb Z}^2$

that can be described within the framework of group homomorphisms).

Following [Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8], we say that the syndetic supremum of a bounded real-valued

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

-sequence

${\mathbb Z}^2$

-sequence

![]() $\left( a_{n,m} \right)_{(n, m) \in {\mathbb Z}^2}$

is the quantity

$\left( a_{n,m} \right)_{(n, m) \in {\mathbb Z}^2}$

is the quantity

For

![]() $2\times 2$

integer matrices

$2\times 2$

integer matrices

![]() $M_1$

and

$M_1$

and

![]() $M_2$

and

$M_2$

and

![]() $\alpha \in (0,1)$

, we define the ergodic popular difference density by

$\alpha \in (0,1)$

, we define the ergodic popular difference density by

where the infimum is taken over all ergodic

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

-systems

${\mathbb Z}^2$

-systems

![]() $\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_{\vec {n}})_{\vec {n} \in {\mathbb Z}^2} \right)$

and sets

$\left( X, \mathcal {X}, \mu , (T_{\vec {n}})_{\vec {n} \in {\mathbb Z}^2} \right)$

and sets

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

with

![]() $\mu (A) = \alpha $

. This can be seen as an ergodic-theoretic analogue to the popular difference density defined in [Reference Sah, Sawhney and Zhao26]. It is natural to ask if

$\mu (A) = \alpha $

. This can be seen as an ergodic-theoretic analogue to the popular difference density defined in [Reference Sah, Sawhney and Zhao26]. It is natural to ask if

![]() $\text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

coincides with the finitary combinatorial quantity

$\text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

coincides with the finitary combinatorial quantity

![]() $\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

. Standard tools for translating between ergodic theory and combinatorics, such as Furstenberg’s correspondence principle, are insufficient for resolving this question, and we do not know the answer in general. However, in special cases where

$\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

. Standard tools for translating between ergodic theory and combinatorics, such as Furstenberg’s correspondence principle, are insufficient for resolving this question, and we do not know the answer in general. However, in special cases where

![]() $\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

is known, it is in agreement with the values of

$\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

is known, it is in agreement with the values of

![]() $\text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

displayed in Table 1 below, and we suspect that

$\text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

displayed in Table 1 below, and we suspect that

![]() $\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha ) = \text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

in the remaining cases (see Subsection 7.3 below for additional remarks on (combinatorial) popular difference densities for matrix patterns in

$\text {pdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha ) = \text {epdd}_{M_1,M_2}(\alpha )$

in the remaining cases (see Subsection 7.3 below for additional remarks on (combinatorial) popular difference densities for matrix patterns in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

).

${\mathbb Z}^2$

).

Table 1 Ergodic popular difference densities for 3-point matrix patterns in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

${\mathbb Z}^2$

Theorem 1.11 provides a sufficient condition on the matrices

![]() $M_1$

and

$M_1$

and

![]() $M_2$

to guarantee that

$M_2$

to guarantee that

![]() $\text {epdd}_{M_1, M_2}(\alpha ) \ge \alpha ^3$

for

$\text {epdd}_{M_1, M_2}(\alpha ) \ge \alpha ^3$

for

![]() $\alpha \in (0,1)$

. We now seek to describe the quantity

$\alpha \in (0,1)$

. We now seek to describe the quantity

![]() $\text {epdd}_{M_1, M_2}(\alpha )$

for any pair of

$\text {epdd}_{M_1, M_2}(\alpha )$

for any pair of

![]() $2\times 2$

integer matrices

$2\times 2$

integer matrices

![]() $M_1$

and

$M_1$

and

![]() $M_2$

. Table 1 summarises ergodic popular difference densities for all 3-point matrix configurations in

$M_2$

. Table 1 summarises ergodic popular difference densities for all 3-point matrix configurations in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

(for matrices

${\mathbb Z}^2$

(for matrices

![]() $M_1, M_2$

, we let

$M_1, M_2$

, we let

![]() $r(M_1,M_2)$

be a list of the ranks of

$r(M_1,M_2)$

be a list of the ranks of

![]() $M_1$

,

$M_1$

,

![]() $M_2$

and

$M_2$

and

![]() $M_2 - M_1$

in decreasing order, and we denote by

$M_2 - M_1$

in decreasing order, and we denote by

![]() $[M_1,M_2]$

the commutator

$[M_1,M_2]$

the commutator

![]() $M_1M_2 - M_2M_1$

).

$M_1M_2 - M_2M_1$

).

The cases

![]() $r(M_1, M_2) = (2,2,2)$

and

$r(M_1, M_2) = (2,2,2)$

and

![]() $r(M_1, M_2) = (2,2,1)$

are covered directly by [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Theorem 1.10] and Theorem 1.11, respectively. Indeed, a matrix M has full rank if and only if the subgroup

$r(M_1, M_2) = (2,2,1)$

are covered directly by [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Theorem 1.10] and Theorem 1.11, respectively. Indeed, a matrix M has full rank if and only if the subgroup

![]() $M({\mathbb Z}^2) \subseteq {\mathbb Z}^2$

has finite index. More precisely,

$M({\mathbb Z}^2) \subseteq {\mathbb Z}^2$

has finite index. More precisely,

$$ \begin{align*} [{\mathbb Z}^2 : M({\mathbb Z}^2)] = \begin{cases} \left| \det(M) \right|, & \text{if}~\det(M) \ne 0; \\ \infty, & \text{if}~\det(M) = 0. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} [{\mathbb Z}^2 : M({\mathbb Z}^2)] = \begin{cases} \left| \det(M) \right|, & \text{if}~\det(M) \ne 0; \\ \infty, & \text{if}~\det(M) = 0. \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

The remaining cases are proved in Section 7.

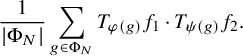

1.5 Preliminary remarks on characteristic factors

In this paper, we approach multiple recurrence problems by determining and utilising the so-called characteristic factors, which are the factors that are responsible for the limiting behaviour of the quantity

in ergodic G-systems (see Subsection 2.2 for a discussion of factors in general and Definition 3.3 for a definition of characteristic factors). For

![]() ${\mathbb Z}$

-actions, there are two different approaches to characteristic factors for linear averages, developed independently by Host and Kra [Reference Host and Kra23] and by Ziegler [Reference Ziegler30], giving rise to factors that coincide (see [Reference Bergelson5, Appendix A]). However, in the context of G-actions, where G is an arbitrary (nonfinitely generated) countable discrete abelian group, the approaches of Host–Kra and of Ziegler may produce different factors (see Subsection 2.6 below for more details).

${\mathbb Z}$

-actions, there are two different approaches to characteristic factors for linear averages, developed independently by Host and Kra [Reference Host and Kra23] and by Ziegler [Reference Ziegler30], giving rise to factors that coincide (see [Reference Bergelson5, Appendix A]). However, in the context of G-actions, where G is an arbitrary (nonfinitely generated) countable discrete abelian group, the approaches of Host–Kra and of Ziegler may produce different factors (see Subsection 2.6 below for more details).

Our work, thus, leads to the general open question of how, in the setup of countable discrete abelian groups, the Host–Kra factors are related to the actual characteristic factors of the corresponding multiple ergodic averages (the factors obtained by Ziegler’s approach). Discerning the relationship between the Host–Kra factors and the characteristic factors may lead to a better understanding of the quantities

where

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

is a G-system,

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

is a G-system,

![]() $A \in \mathcal {X}$

and

$A \in \mathcal {X}$

and

![]() $\varphi _i:G\rightarrow G$

are homomorphisms or, more generally, polynomial maps.

$\varphi _i:G\rightarrow G$

are homomorphisms or, more generally, polynomial maps.

1.6 Structure of the paper

The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we introduce notation and conventions that we use throughout the paper.

Proofs of the main results appear in Sections 3–6. First, in Section 3, we establish characteristic factors for the multiple ergodic averages

when

![]() $(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index in G and prove Theorem 1.11. Then, in Section 4, we use an extension trick to simplify the characteristic factors, and in Section 5, prove a new limit formula for the extension system, leading to a proof of Theorem 1.13. Finally, we prove Theorem 1.14 in Section 6.

$(\psi -\varphi )(G)$

has finite index in G and prove Theorem 1.11. Then, in Section 4, we use an extension trick to simplify the characteristic factors, and in Section 5, prove a new limit formula for the extension system, leading to a proof of Theorem 1.13. Finally, we prove Theorem 1.14 in Section 6.

The final two sections contain applications of the main results. Using Theorem 1.11 together with additional tools from [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Reference Bergelson, Host and Kra8, Reference Bergelson and Leibman9, Reference Chu13, Reference Donoso and Sun16], we compute ergodic popular difference densities for 3-point matrix patterns in

![]() ${\mathbb Z}^2$

. In Section 8, we extend the main results (Theorems 1.11 and 1.13) to the setting of cancellative abelian semigroups.

${\mathbb Z}^2$

. In Section 8, we extend the main results (Theorems 1.11 and 1.13) to the setting of cancellative abelian semigroups.

2 Preliminaries

The goal of this section is to introduce some notations and objects that will play an important role in this paper. Throughout this section, we let G denote an arbitrary countable discrete abelian group and

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

a G-system.

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

a G-system.

2.1 Uniform Cesàro limits

The large intersection property of a family

![]() $\{\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k\}$

is related to the limit behaviour of the multiple ergodic averages

$\{\varphi _1, \dots , \varphi _k\}$

is related to the limit behaviour of the multiple ergodic averages

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{|\Phi_N|} \sum_{g \in \Phi_N} \prod_{i=1}^k{T_{\varphi_i(g)}f_i}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{|\Phi_N|} \sum_{g \in \Phi_N} \prod_{i=1}^k{T_{\varphi_i(g)}f_i}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $(\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is a Følner sequenceFootnote 2 in G and

$(\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

is a Følner sequenceFootnote 2 in G and

![]() $f_1, \dots , f_k \in L^{\infty }(\mu )$

. By [Reference Austin3] and [Reference Zorin-Kranich32], the quantity in (4) converges in

$f_1, \dots , f_k \in L^{\infty }(\mu )$

. By [Reference Austin3] and [Reference Zorin-Kranich32], the quantity in (4) converges in

![]() $L^2(\mu )$

as

$L^2(\mu )$

as

![]() $N \to \infty $

, and the limit is independent of the choice of Følner sequence

$N \to \infty $

, and the limit is independent of the choice of Følner sequence

![]() $(\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

. For more concise notation, we define the uniform Cesàro limit

$(\Phi _N)_{N \in \mathbb N}$

. For more concise notation, we define the uniform Cesàro limit

![]() $x = \text {UC -}\lim _{g \in G}{x_g}$

if

$x = \text {UC -}\lim _{g \in G}{x_g}$

if

![]() $\frac {1}{|\Phi _N|} \sum _{g \in \Phi _N}{x_g} \to x$

for every Følner sequence

$\frac {1}{|\Phi _N|} \sum _{g \in \Phi _N}{x_g} \to x$

for every Følner sequence

![]() $(\Phi _N)_{N\in \mathbb N}$

in G.

$(\Phi _N)_{N\in \mathbb N}$

in G.

One crucial tool for handling uniform Cesàro limits is the following version of the van der Corput differencing trick:

Lemma 2.1 (van der Corput lemma, cf. [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2], Lemma 2.2)

Let

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

be a Hilbert space and G a countable amenable group. Let

$\mathcal {H}$

be a Hilbert space and G a countable amenable group. Let

![]() $(u_g)_{g\in G}$

be a bounded sequence in

$(u_g)_{g\in G}$

be a bounded sequence in

![]() $\mathcal {H}$

. If

$\mathcal {H}$

. If

![]() $\text {UC -}\lim _{g\in G} \left\langle u_{g+h}, u_g \right\rangle $

exists for every

$\text {UC -}\lim _{g\in G} \left\langle u_{g+h}, u_g \right\rangle $

exists for every

![]() $h\in G$

, and

$h\in G$

, and

then,

strongly.

Another useful tool for computing uniform Cesàro limits is the following ‘Fubini’ trick, which we use extensively in Section 7:

Lemma 2.2 ([Reference Bergelson and Leibman9], special case of Lemma 1.1)

Let G and H be countable discrete amenable groups, and let

![]() $(v_{h,g})_{(h,g) \in H \times G}$

be a bounded sequence. Suppose

$(v_{h,g})_{(h,g) \in H \times G}$

be a bounded sequence. Suppose

exists, and for every

![]() $g \in G$

,

$g \in G$

,

exists. Then

2.2 Factors

A factor of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

is a G-system

$\textbf {X}$

is a G-system

![]() $\textbf {Y}=(Y,\mathcal {Y},\nu ,(S_g)_{g\in G})$

together with a measurable map

$\textbf {Y}=(Y,\mathcal {Y},\nu ,(S_g)_{g\in G})$

together with a measurable map

![]() $\pi :X\to Y$

, such that

$\pi :X\to Y$

, such that

![]() $\pi _*\mu = \nu $

and

$\pi _*\mu = \nu $

and

![]() $\pi \circ T_g = S_g\circ \pi $

for all

$\pi \circ T_g = S_g\circ \pi $

for all

![]() $g\in G$

. There is a natural one-to-one correspondence between factors and

$g\in G$

. There is a natural one-to-one correspondence between factors and

![]() $(T_g)_{g \in G}$

-invariant sub-

$(T_g)_{g \in G}$

-invariant sub-

![]() $\sigma $

-algebras of

$\sigma $

-algebras of

![]() $\mathcal {X}$

. Throughout the paper, we freely move between the system

$\mathcal {X}$

. Throughout the paper, we freely move between the system

![]() $\textbf {Y}$

and the

$\textbf {Y}$

and the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

![]() $\pi ^{-1}(\mathcal {Y})$

and refer to both of them as factors of

$\pi ^{-1}(\mathcal {Y})$

and refer to both of them as factors of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

. Given

$\textbf {X}$

. Given

![]() $f\in L^2(\mu )$

, we denote by

$f\in L^2(\mu )$

, we denote by

![]() $E(f|\mathcal {Y})$

the conditional expectation of f with respect to the

$E(f|\mathcal {Y})$

the conditional expectation of f with respect to the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

![]() $\pi ^{-1}(\mathcal {Y})$

. We say that f is measurable with respect to

$\pi ^{-1}(\mathcal {Y})$

. We say that f is measurable with respect to

![]() $\mathcal {Y}$

if

$\mathcal {Y}$

if

![]() $f=E(f|\mathcal {Y})$

.

$f=E(f|\mathcal {Y})$

.

2.3 Factor of invariant sets

Let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system. We write

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu , (T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system. We write

![]() $\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

for the sub-

$\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

for the sub-

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra of G-invariant sets. We say that

$\sigma $

-algebra of G-invariant sets. We say that

![]() $\textbf {X}$

is ergodic if

$\textbf {X}$

is ergodic if

![]() $\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

is the

$\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

is the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra comprised of null and conull subsets of

$\sigma $

-algebra comprised of null and conull subsets of

![]() $(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

. For a subgroup

$(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

. For a subgroup

![]() $H \le G$

, we denote by

$H \le G$

, we denote by

![]() $\mathcal {I}_H(X)$

the sub-

$\mathcal {I}_H(X)$

the sub-

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra of H-invariant sets. Given a homomorphism

$\sigma $

-algebra of H-invariant sets. Given a homomorphism

![]() $\varphi :G\rightarrow G$

, it is convenient to denote by

$\varphi :G\rightarrow G$

, it is convenient to denote by

![]() $\mathcal {I}_{\varphi }(X)$

the

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi }(X)$

the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

![]() $\mathcal {I}_{\varphi (G)}(X)$

.

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi (G)}(X)$

.

2.4 Host–Kra factors

The Gowers–Host–Kra seminorms are an ergodic-theoretic version of the uniformity norms introduced by Gowers in [Reference Gowers22]. These seminorms were first introduced by Host and Kra in [Reference Host and Kra23] in the case of ergodic

![]() $\mathbb {Z}$

-systems, and then generalised by Chu, Frantzikinakis and Host to

$\mathbb {Z}$

-systems, and then generalised by Chu, Frantzikinakis and Host to

![]() $\mathbb {Z}$

-systems that are not necessarily ergodic in [Reference Chu, Frantzikinakis and Host14]. In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10, Appendix A], a general theory of Gower–Host–Kra seminorms is developed for (not necesssarily ergodic) G-systems, where G is an arbitrary countable discrete abelian group.

$\mathbb {Z}$

-systems that are not necessarily ergodic in [Reference Chu, Frantzikinakis and Host14]. In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10, Appendix A], a general theory of Gower–Host–Kra seminorms is developed for (not necesssarily ergodic) G-systems, where G is an arbitrary countable discrete abelian group.

Definition 2.3. Let G be a countable discrete abelian group, and let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system. Let

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system. Let

![]() $f \in L^{\infty } (X)$

, and let

$f \in L^{\infty } (X)$

, and let

![]() $k\geq 1$

be an integer. The Gowers–Host–Kra seminorm

$k\geq 1$

be an integer. The Gowers–Host–Kra seminorm

![]() $\|f\|_{U^k(G)}$

of order k of f is defined recursively by the formula

$\|f\|_{U^k(G)}$

of order k of f is defined recursively by the formula

for

![]() $k=1$

, and

$k=1$

, and

for

![]() $k>1$

, where

$k>1$

, where

![]() .

.

In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10, Appendix A], it is shown that the Gower–Host–Kra seminorms for general G-systems are indeed seminorms. Moreover, these seminorms correspond to factors of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

.

$\textbf {X}$

.

Proposition 2.4 (cf. [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10], Proposition 1.10)

Let G be a countable discrete abelian group, let

![]() $\textbf {X}$

be a G-system and let

$\textbf {X}$

be a G-system and let

![]() $k\geq 0$

. There exists a unique (up to isomorphism) factor

$k\geq 0$

. There exists a unique (up to isomorphism) factor

![]() $\mathbf {Z}^{k}(X)=\left( Z^{k}(X),\mathcal {Z}^{k}(X),\mu _k,(T^{(k)}_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

of

$\mathbf {Z}^{k}(X)=\left( Z^{k}(X),\mathcal {Z}^{k}(X),\mu _k,(T^{(k)}_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

with the property that for every

$\textbf {X}$

with the property that for every

![]() $f\in L^{\infty } (X)$

,

$f\in L^{\infty } (X)$

,

![]() $\|f\|_{U^{k+1}(X)}=0$

if and only if

$\|f\|_{U^{k+1}(X)}=0$

if and only if

![]() $E(f|\mathcal {Z}^{k}(X))=0$

.

$E(f|\mathcal {Z}^{k}(X))=0$

.

The factors

![]() $\mathbf {Z}^k$

guaranteed by Proposition 2.4 are called the Host–Kra factors of

$\mathbf {Z}^k$

guaranteed by Proposition 2.4 are called the Host–Kra factors of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

.

$\textbf {X}$

.

Let

![]() $\textbf {X}=\left(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

be a G-system. Then,

$\textbf {X}=\left(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g \in G} \right)$

be a G-system. Then,

![]() $\mathcal {Z}^0(X)$

is the same as the

$\mathcal {Z}^0(X)$

is the same as the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

![]() $\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

. In particular, if

$\mathcal {I}_G(X)$

. In particular, if

![]() $\textbf {X}$

is ergodic, then

$\textbf {X}$

is ergodic, then

![]() $\mathcal {Z}^0(X)$

is trivial. In the literature,

$\mathcal {Z}^0(X)$

is trivial. In the literature,

![]() $\mathbf {Z}^1(X)$

is often called the Kronecker factor, and

$\mathbf {Z}^1(X)$

is often called the Kronecker factor, and

![]() $\mathbf {Z}^2(X)$

the Conze–Lesigne or quasi-affine factor of

$\mathbf {Z}^2(X)$

the Conze–Lesigne or quasi-affine factor of

![]() $\textbf {X}$

.

$\textbf {X}$

.

We summarise some basic results about the Host–Kra factors.

Theorem 2.5. Let G be a countable discrete abelian group, and let

![]() $\textbf {X} = (X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a ergodic G-system. Then,

$\textbf {X} = (X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a ergodic G-system. Then,

-

(i) For every

$k\geq 1$

,

$k\geq 1$

,

$\mathcal {Z}^{k-1}(X)\preceq \mathcal {Z}^{k}(X)$

. In other words,

$\mathcal {Z}^{k-1}(X)\preceq \mathcal {Z}^{k}(X)$

. In other words,

$\mathbf {Z}^{k-1}(X)$

is a factor of

$\mathbf {Z}^{k-1}(X)$

is a factor of

$\mathbf {Z}^k(X)$

. In particular,

$\mathbf {Z}^k(X)$

. In particular,

$\mathcal {I}(X)\preceq \mathcal {Z}^k(X)$

for every

$\mathcal {I}(X)\preceq \mathcal {Z}^k(X)$

for every

$k\geq 0$

.

$k\geq 0$

. -

(ii) The Kronecker factor of

$\textbf {X}$

is isomorphic to a rotation on a compact abelian group. Namely, there exists a homomorphism

$\textbf {X}$

is isomorphic to a rotation on a compact abelian group. Namely, there exists a homomorphism

$\alpha :G\rightarrow Z$

into a compact abelian group

$\alpha :G\rightarrow Z$

into a compact abelian group

$(Z,+)$

, such that

$(Z,+)$

, such that

$\mathbf {Z}^1(X)$

is isomorphic to

$\mathbf {Z}^1(X)$

is isomorphic to

$(Z, (R_g)_{g \in G})$

, where

$(Z, (R_g)_{g \in G})$

, where

$R_gz = z+\alpha (g)$

.

$R_gz = z+\alpha (g)$

. -

(iii) For every

$k\geq 1$

, if

$k\geq 1$

, if

$\textbf {X}$

is ergodic, then

$\textbf {X}$

is ergodic, then

$\mathbf {Z}^k(X)$

is an extension of

$\mathbf {Z}^k(X)$

is an extension of

$\mathbf {Z}^{k-1}(X)$

by a compact abelian group

$\mathbf {Z}^{k-1}(X)$

by a compact abelian group

$(H,+)$

and a cocycle

$(H,+)$

and a cocycle

$\rho :G\times Z^{k-1}(X)\rightarrow H$

. Namely,

$\rho :G\times Z^{k-1}(X)\rightarrow H$

. Namely,

$Z^k(X)=Z^{k-1}(X)\times H$

as measure spaces, and the action is given by

$Z^k(X)=Z^{k-1}(X)\times H$

as measure spaces, and the action is given by

$T^{(k)}_g (z,h) = (T^{(k-1)}_g z, h+\rho (g,z))$

.

$T^{(k)}_g (z,h) = (T^{(k-1)}_g z, h+\rho (g,z))$

.

Proof. The proof of

![]() $(i)$

is an immediate consequence of the monotonicity of the seminorms (see [Reference Host and Kra23, Corollary 4.4]). The proof of

$(i)$

is an immediate consequence of the monotonicity of the seminorms (see [Reference Host and Kra23, Corollary 4.4]). The proof of

![]() $(ii)$

in the generality of countable discrete abelian groups can be found in [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Lemma 2.4]. The proof of

$(ii)$

in the generality of countable discrete abelian groups can be found in [Reference Ackelsberg, Bergelson and Best2, Lemma 2.4]. The proof of

![]() $(iii)$

can be found for

$(iii)$

can be found for

![]() $\mathbb {Z}$

-actions in [Reference Host and Kra23, Proposition 6.3], and the same proof works for arbitrary countable discrete abelian groups.

$\mathbb {Z}$

-actions in [Reference Host and Kra23, Proposition 6.3], and the same proof works for arbitrary countable discrete abelian groups.

2.5 Joins and meets of factors

Let G be a countable discrete abelian group, let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system and let

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_g)_{g\in G})$

be a G-system and let

![]() $\varphi ,\psi :G\rightarrow G$

be arbitrary homomorphisms.

$\varphi ,\psi :G\rightarrow G$

be arbitrary homomorphisms.

-

1. Let

$\mathcal {Z}^1_{\varphi }(X)$

, or just

$\mathcal {Z}^1_{\varphi }(X)$

, or just

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi }(X)$

, denote the

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi }(X)$

, denote the

$\sigma $

-algebra of the Kronecker factor of X with respect to the action of

$\sigma $

-algebra of the Kronecker factor of X with respect to the action of

$\varphi (G)$

, that is, the

$\varphi (G)$

, that is, the

$\sigma $

-algebra of the factor

$\sigma $

-algebra of the factor

$\mathbf {Z}^1_{\varphi }(X)$

obtained by applying Proposition 2.4 for the G-system

$\mathbf {Z}^1_{\varphi }(X)$

obtained by applying Proposition 2.4 for the G-system

$(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_{\varphi (g)})_{g\in G})$

and

$(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,(T_{\varphi (g)})_{g\in G})$

and

$k=1$

. More generally, let H be a subgroup of G and

$k=1$

. More generally, let H be a subgroup of G and

$k\geq 1$

, we let

$k\geq 1$

, we let

$\mathcal {Z}^k_H(X)$

denote the

$\mathcal {Z}^k_H(X)$

denote the

$\sigma $

-algebra of the k-th Host–Kra factor

$\sigma $

-algebra of the k-th Host–Kra factor

$\mathbf {Z}^k_H(X)$

with respect to the action of H.

$\mathbf {Z}^k_H(X)$

with respect to the action of H. -

2. Let

$\mathcal {A}$

,

$\mathcal {A}$

,

$\mathcal {A}_1,\mathcal {A}_2$

be

$\mathcal {A}_1,\mathcal {A}_2$

be

$\sigma $

-algebras on X. Then,

$\sigma $

-algebras on X. Then,-

○ We write

$\mathcal {A}\preceq \mathcal {X}$

if the

$\mathcal {A}\preceq \mathcal {X}$

if the

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\mathcal {A}$

is a sub-

$\mathcal {A}$

is a sub-

$\sigma $

-algebra of

$\sigma $

-algebra of

$\mathcal {X}$

.

$\mathcal {X}$

. -

○ We let

$\mathcal {A}_1\lor \mathcal {A}_2$

denote the join of

$\mathcal {A}_1\lor \mathcal {A}_2$

denote the join of

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, that is, the

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, that is, the

$\sigma $

-algebra generated by

$\sigma $

-algebra generated by

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

in

$\mathcal {A}_2$

in

$\mathcal {X}$

.

$\mathcal {X}$

. -

○ We let

$\mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2$

denote the meet of

$\mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2$

denote the meet of

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, that is, the maximal

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, that is, the maximal

$\sigma $

-algebra which is also a sub-

$\sigma $

-algebra which is also a sub-

$\sigma $

-algebra of

$\sigma $

-algebra of

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

.

$\mathcal {A}_2$

. -

○ We say that

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

are

$\mathcal {A}_2$

are

$\mu $

-independent if their meet is trivial modulo

$\mu $

-independent if their meet is trivial modulo

$\mu $

-null sets.

$\mu $

-null sets. -

○ More generally, we say that

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

are relatively independent over the

$\mathcal {A}_2$

are relatively independent over the

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\mathcal {A}$

if

$\mathcal {A}$

if

$\mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2\preceq \mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2\preceq \mathcal {A}$

.

-

-

3. We let

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

denote the meet of

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

denote the meet of

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {I}_{\varphi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {I}_{\psi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {I}_{\psi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

the meet of

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

the meet of

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi }(X)$

and

$\mathcal {Z}_{\psi }(X)$

. We let

$\mathcal {Z}_{\psi }(X)$

. We let

$\mathbf {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

denote the factor of

$\mathbf {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

denote the factor of

$\textbf {X}$

which corresponds to the

$\textbf {X}$

which corresponds to the

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\sigma $

-algebra

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

.

$\mathcal {Z}_{\varphi ,\psi }(X)$

.

The next two lemmas give convenient alternative descriptions of independent and relatively independent

![]() $\sigma $

-algebras. These results are classical and can be found, for example, in [Reference Zimmer31, Proposition 1.4]; we provide short proofs for the convenience of the reader.

$\sigma $

-algebras. These results are classical and can be found, for example, in [Reference Zimmer31, Proposition 1.4]; we provide short proofs for the convenience of the reader.

Proposition 2.6 (Independent

$\sigma $

-algebras)

$\sigma $

-algebras)

Let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

be a probability space. Two

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

be a probability space. Two

![]() $\sigma $

-algebras

$\sigma $

-algebras

![]() $\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

![]() $\mathcal {A}_2$

on X are

$\mathcal {A}_2$

on X are

![]() $\mu $

-independent if and only if the following equivalent conditions hold:

$\mu $

-independent if and only if the following equivalent conditions hold:

-

(i) Any function

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

measurable with respect to

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

simultaneously is a constant

$\mathcal {A}_2$

simultaneously is a constant

$\mu $

-almost everywhere.

$\mu $

-almost everywhere. -

(ii) If

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

is measurable with respect to

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$g\in L^{\infty }(X)$

is measurable with respect to

$g\in L^{\infty }(X)$

is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, then

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, then  $$ \begin{align*} \int_X f\cdot g~d\mu = \int_X f~d\mu \cdot \int_X g~d\mu. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \int_X f\cdot g~d\mu = \int_X f~d\mu \cdot \int_X g~d\mu. \end{align*} $$

Proof. The first definition of independence above is clearly equivalent to (i). We prove the equivalence between (i) and (ii).

(i)

![]() $\Rightarrow $

(ii).

$\Rightarrow $

(ii).

where the second equality holds since

![]() $E(f|\mathcal {A}_2)$

is a constant

$E(f|\mathcal {A}_2)$

is a constant

![]() $\mu $

-a.e. by (i).

$\mu $

-a.e. by (i).

For (ii)

![]() $\Rightarrow $

(i), let

$\Rightarrow $

(i), let

![]() $\widetilde {f} = f-\int f d\mu $

. Then,

$\widetilde {f} = f-\int f d\mu $

. Then,

$$ \begin{align*} \|\widetilde{f}\|_{L^2(\mu)}^2 = \int |\widetilde{f}|^2 ~d\mu = \left|\int_X \widetilde{f} ~d\mu\right| ^2=0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \|\widetilde{f}\|_{L^2(\mu)}^2 = \int |\widetilde{f}|^2 ~d\mu = \left|\int_X \widetilde{f} ~d\mu\right| ^2=0. \end{align*} $$

We conclude that

![]() $f=\int fd\mu $

.

$f=\int fd\mu $

.

Proposition 2.7 (Relatively independent

$\sigma $

-algebras)

$\sigma $

-algebras)

Let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

be a probability space. Let

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu )$

be a probability space. Let

![]() $\mathcal {A}_1,\mathcal {A}_2$

be two

$\mathcal {A}_1,\mathcal {A}_2$

be two

![]() $\sigma $

-algebras on X, and let

$\sigma $

-algebras on X, and let

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

be a third

$\mathcal {A}$

be a third

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra, such that

$\sigma $

-algebra, such that

![]() $\mathcal {A}\preceq \mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2$

. Then,

$\mathcal {A}\preceq \mathcal {A}_1\land \mathcal {A}_2$

. Then,

![]() $\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

![]() $\mathcal {A}_2$

are relatively independent with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_2$

are relatively independent with respect to

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

if the following equivalent conditions hold:

$\mathcal {A}$

if the following equivalent conditions hold:

-

(i) Any function

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

measurable with respect to

$f\in L^{\infty }(X)$

measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and

$\mathcal {A}_2$

simultaneously is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_2$

simultaneously is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}$

.

$\mathcal {A}$

. -

(ii) If f is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and g is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_1$

and g is measurable with respect to

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, then

$\mathcal {A}_2$

, then  $$ \begin{align*} E(fg|\mathcal{A})=E(f|\mathcal{A})\cdot E(g|\mathcal{A}). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} E(fg|\mathcal{A})=E(f|\mathcal{A})\cdot E(g|\mathcal{A}). \end{align*} $$

Proof. Condition

![]() $(i)$

is equivalent to the definition of relative independence above. Therefore, it is enough to prove the equivalence of

$(i)$

is equivalent to the definition of relative independence above. Therefore, it is enough to prove the equivalence of

![]() $(i)$

and

$(i)$

and

![]() $(ii)$

.

$(ii)$

.

(i)

![]() $\Rightarrow $

(ii). We have

$\Rightarrow $

(ii). We have

![]() $E(fg|\mathcal {A}_1) = f\cdot E(g|\mathcal {A}_1) = f\cdot E(g|\mathcal {A})$

, where the last equality follows from

$E(fg|\mathcal {A}_1) = f\cdot E(g|\mathcal {A}_1) = f\cdot E(g|\mathcal {A})$

, where the last equality follows from

![]() $(i)$

. Now, by taking the conditional expectation over

$(i)$

. Now, by taking the conditional expectation over

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

, we have

$\mathcal {A}$

, we have

(ii)

![]() $\Rightarrow $

(i). Let

$\Rightarrow $

(i). Let

![]() $\widetilde {f} = f-E(f|\mathcal {A})$

. Then

$\widetilde {f} = f-E(f|\mathcal {A})$

. Then

![]() $E(|\widetilde {f}|^2|\mathcal {A})=E(\widetilde {f}|\mathcal {A})^2 = 0$

. In particular,

$E(|\widetilde {f}|^2|\mathcal {A})=E(\widetilde {f}|\mathcal {A})^2 = 0$

. In particular,

![]() $\int |\widetilde {f}|^2 d\mu = 0$

, thus,

$\int |\widetilde {f}|^2 d\mu = 0$

, thus,

![]() $f=E(f|\mathcal {A})$

.

$f=E(f|\mathcal {A})$

.

2.6 Characteristic factors

Let

![]() $\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,T)$

be an invertible ergodic measure preserving system and

$\textbf {X}=(X,\mathcal {X},\mu ,T)$

be an invertible ergodic measure preserving system and

![]() $f_1,...,f_k\in L^{\infty }(X)$

,

$f_1,...,f_k\in L^{\infty }(X)$

,

![]() $k\geq 0$

. The convergence of the multiple ergodic averages

$k\geq 0$

. The convergence of the multiple ergodic averages

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{in} f_i \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{in} f_i \end{align} $$

in

![]() $L^2(\mu )$

for general k was established by Host and Kra [Reference Host and Kra23] and independently, though somewhat later, by Ziegler [Reference Ziegler30].

$L^2(\mu )$

for general k was established by Host and Kra [Reference Host and Kra23] and independently, though somewhat later, by Ziegler [Reference Ziegler30].

Host and Kra proved convergence by showing that the averages in (5) are controlled by the Gowers–Host–Kra seminorms defined above. This reduces the general convergence problem to convergence under the additional assumption that each function

![]() $f_i$

is measurable with respect to the Host–Kra factor.

$f_i$

is measurable with respect to the Host–Kra factor.

Ziegler, on the other hand, studied the universal (minimal) characteristic factors for the multiple ergodic averages

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{a_in} f_i, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{a_in} f_i, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $a_1,...,a_k\in \mathbb {Z}$

are distinct and nonzero. These are the minimal factors

$a_1,...,a_k\in \mathbb {Z}$

are distinct and nonzero. These are the minimal factors

![]() $\mathcal {Z}_{k-1}(X)$

, such that

$\mathcal {Z}_{k-1}(X)$

, such that

$$ \begin{align*} \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{a_in} f_i=0 \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \prod_{i=1}^k T^{a_in} f_i=0 \end{align*} $$

whenever

![]() $E(f_i|\mathcal {Z}_{k-1}(X))=0$

for some i.

$E(f_i|\mathcal {Z}_{k-1}(X))=0$

for some i.

In [Reference Bergelson5, Appendix A], Leibman proved that, for

![]() ${\mathbb Z}$

-systems, the factors studied by Host and Kra coincide with the factors studied by Ziegler, thus giving these factors the name Host–Kra–Ziegler factors. Using Følner sequences in order to define averages, one can generalise the above to arbitrary countable discrete abelian groups (or even more generally, to amenable groups). However, in the setting of general abelian groups, Host–Kra factors may no longer coincide with the characteristic factors for averages of the form

${\mathbb Z}$

-systems, the factors studied by Host and Kra coincide with the factors studied by Ziegler, thus giving these factors the name Host–Kra–Ziegler factors. Using Følner sequences in order to define averages, one can generalise the above to arbitrary countable discrete abelian groups (or even more generally, to amenable groups). However, in the setting of general abelian groups, Host–Kra factors may no longer coincide with the characteristic factors for averages of the form

$$ \begin{align*} \text{UC -}\lim_{g \in G} \prod_{i=1}^k T_{a_ig} f_i. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \text{UC -}\lim_{g \in G} \prod_{i=1}^k T_{a_ig} f_i. \end{align*} $$

We give a very simple example. Let p be a prime number and

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p$

be the group with p elements. We denote by

$\mathbb {F}_p$

be the group with p elements. We denote by

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p^{\infty }$

the direct sum of countably many copies of

$\mathbb {F}_p^{\infty }$

the direct sum of countably many copies of

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p$

. In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10], it is shown that there are many nontrivial ergodic

$\mathbb {F}_p$

. In [Reference Bergelson, Tao and Ziegler10], it is shown that there are many nontrivial ergodic

![]() $\mathbb {F}_p^{\infty }$

-systems with nontrivial Host–Kra factors

$\mathbb {F}_p^{\infty }$

-systems with nontrivial Host–Kra factors

![]() $\mathcal {Z}^k(X)$

for any

$\mathcal {Z}^k(X)$

for any

![]() $k \ge 0$

. However, the only characteristic factor for the average

$k \ge 0$

. However, the only characteristic factor for the average

is

![]() $\mathcal {X}$

. Indeed, since

$\mathcal {X}$

. Indeed, since

![]() $T_{pg}=Id$