No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

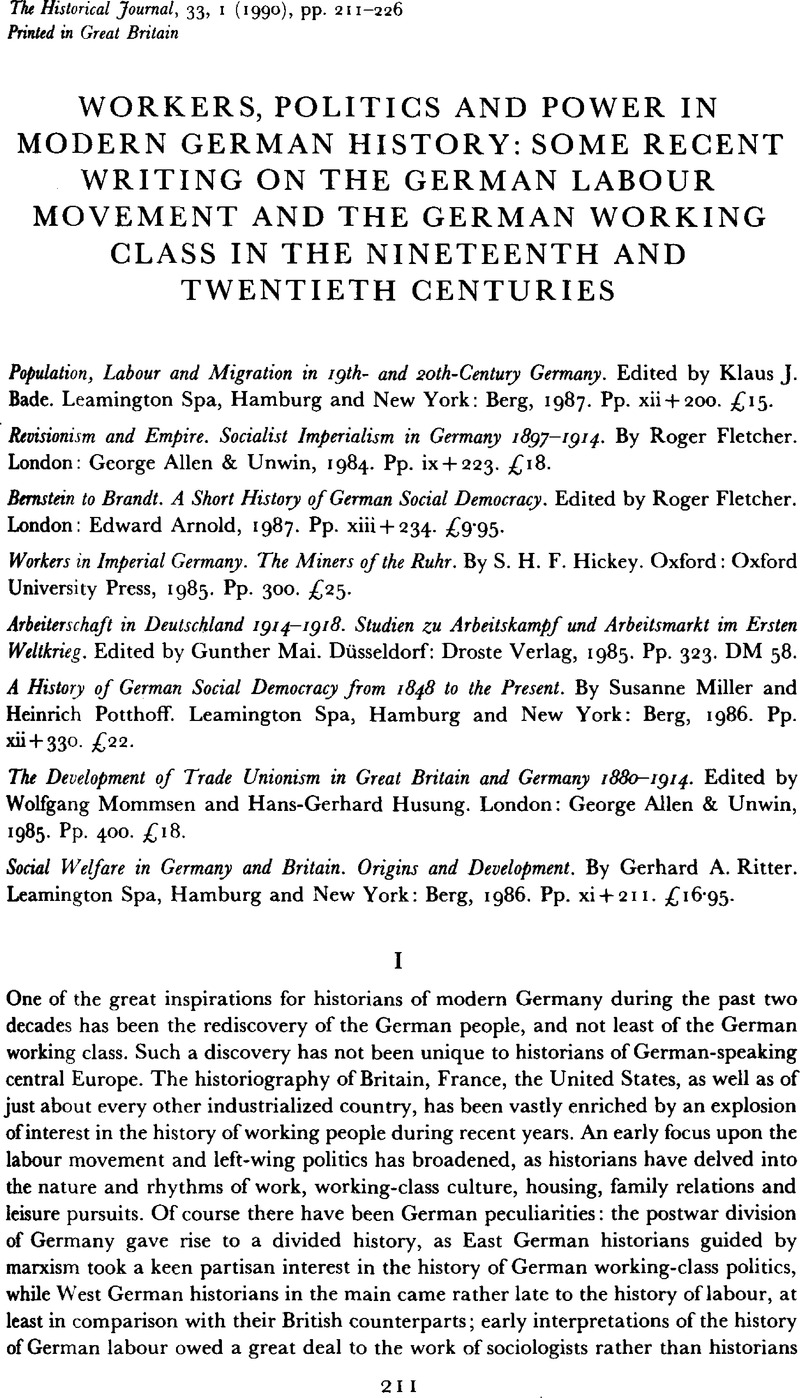

Workers, Politics and Power in Modern German History: Some Recent Writing on the German Labour Movement and the German Working Class in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1990

References

1 See Evans, Richard J., ‘The sociological interpretation of German labour history’, in Evans, Richard J. (ed.), The German working class 1888–1933. The politics of everyday life (London, 1982), pp. 15–53Google Scholar.

2 For an excellent recent discussion of the literature on labour in Nazi Germany, see Herbert, Ulrich, ‘Arbeiterschaft im “Dritten Reich”. Zwischenbilanz und offene Fragen’, Geschichte und Gesellschaft, XV (1989), 320–60Google Scholar.

3 For example, see Reulecke, Jürgen (ed.), Arbeiterbewegung an Rhein und Ruhr (Wuppertal, 1974)Google Scholar; Tenfelde, Klaus, Sozialgeschichte der Bergarbeiterschaft an der Ruhr in 19. Jahrhundert (Bonn, 1977)Google Scholar; Mommsen, Hans and Borsdorf, Ulrich (eds.), Glück auf, Kameraden! Die Bergarbeiter und ihre Organisationen in Deutschland (Cologne, 1979)Google Scholar; Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef, Leben vor Ort. Ruhrbergleute und Ruhrbergbau 1889–1919 (Munich, 1983)Google Scholar.

4 Hobsbawm, E. J., Labouring men (London, 1968), p. 9Google Scholar.

5 Brüggemeier, Leben vor Orl.

6 For greater detail, and for an interesting parallel to Franz Brüggemeier's study of Ruhr miners, see Grüttner's monograph on Hamburg dock labour in the Empire, Arbeitswelt an der Wasserkante. Sozialgeschichte der Hamburger Hafenarbeiter 1886–1914 (Göttingen, 1984)Google Scholar.

7 It is worth repeating Dick Geary's observation here: ‘In Britain in 1910 900,000 miners, 500,000 railway workers, 460,000 textile operatives and 230,000 metalworkers benefited from [collective] agreements. The equivalent figures for Germany only three years later are staggeringly different: 16,000 textile workers, 1,376 metalworkers and a mere 82 miners.’ See Geary, Dick, ‘Identifying militancy: the assessment of working-class attitudes towards state and society’, in Evans, (ed.), The German working class, p. 239Google Scholar.

8 Ritter, Gerhard A., Die Arbeiterbewegung im wilhelminischen Reich. Die Sozialdemokratishe Partei und die Freien Gewerkschaften 1890–1900 (Berlin, 1959)Google Scholar.

9 Tennstedt, Florian, Vom Proleten zum Industriearbeiter. Arbeiterbewegung und Sozialpolitik in Deutsckland 1880 bis 1914 (Cologne, 1983), p. 16Google Scholar.

10 Mai, Gunther, Kriegswirtschaft und Arbeiterbewegung in Württemberg 1914–1918 (Stuttgart, 1983)Google Scholar.

11 Neihuss, Merith, ‘Arbeitslosigkeit in Augsburg und Linz, 1914–1924’, in Archiv für Sozialgeschichte, XXII (1982), 133–58Google Scholar; Niehuss, Merith, Arbeiterschaft in Krieg und Inflation. Soziale Schichtung und Lage der Arbeiter in Augsburg und Linz 1910 bis 1925 (Berlin and New York, 1985)Google Scholar.

12 The second instalment of this story, so to speak, can be found in Niehuss, Merith, ‘From welfare provision to social insurance: the unemployed in Augsburg 1918–1927’, in Evans, Richard J. and Geary, Dick (eds.), The German unemployed. Experiences and consequences of mass unemployment from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich (London, 1987), pp. 44–72Google Scholar.

13 Feldman, Gerald D., Army industry and labor in Germany 1914–1918 (Princeton, 1966)Google Scholar.

14 Bieber, Hans-Joachim, Gewerkschaften in Krieg und Revolution. Arbeiterbewegung, Industrie, Staat und Militär in Deutschland 1914–1920 (Hamburg, 1981)Google Scholar.

15 Plumpe presents a convincing case that the chemical industry played a much more important role in the planning of the German war economy than did heavy industry, despite the stress often given by historians to the latter. Indeed, one of the merits of his article is that it offers considerable insight into the perspective of the employers, while remaining refreshingly free from the hostile polemic that so often has characterised discussion of German businessmen.

16 Feldman, , Army industry and labor, p. 247Google Scholar.

17 Potthoff, Heinrich, Gewerkschaften und Politik zwischen Revolution und Inflation (Düsseldorf, 1979)Google Scholar.

18 See, in particular, Peukert, Detlev and Reulecke, Jürgen (eds.), Die Reihen fast geschlossen. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Alltags unterm Nationalsozialismus (Wuppertal, 1981)Google Scholar; Peukert, Detlev J. K., Inside Nazi Germany. Conformity, opposition and racism in everyday life (London, 1987)Google Scholar.

19 See Winkler, Heinrich August, Von der Revolution zu Stabilisierung. Arbeiter und Arbeiterbewegung in der Weimarer Republik 1918 bis 1924 (Bonn, 1984), pp. 206–16Google Scholar.

20 For a critical assessment of the historiography as well as the history of the German Revolution, see Mommsen, Wolfgang J., ‘The German revolution 1918–1920: political revolution and social protest movement’, in Bessel, Richard and Feuchtwanger, E. J. (eds), Social change and political development in Weimar Germany (London, 1981), pp. 21–54Google Scholar.