INTRODUCTION

In his seminal study of public memory and urban politics, Andreas Huyssen writes of Berlin as a “palimpsest”, describing how the contemporary city incorporates and reworks numerous elements of a disparate and often troubled past.Footnote 1 Huyssen's engagement with Berlin on such terms is a fitting point of departure for considering many modern cities. Situated at the southern tip of Africa, the built environment of Cape Town in South Africa is a multi-layered tapestry of societies past and present. Cape Town functions as the provincial capital of Western Cape Province and serves as a prime tourist destination for international visitors. Depictions of the city in tourist publications as an inclusive world of adventuring, beaches, mountain backdrops, fine dining, and warm weather sometimes sit at odds with the uncomfortable history of colonialism, enslavement, and formal racial segregation that have shaped Cape Town's built features.Footnote 2 In spite of the Western Cape being the former epicentre of the slave trade to Southern Africa, efforts to confront this history in the city remain fitful and highly contested. These contestations are heavily interlinked with the socio-economic and urban spatial legacies of the white-minority National Party's apartheid system of racial segregation, which was used to govern South Africa between 1948 and 1994.

This article examines remembrance in Cape Town over time, exploring how different actors and groups have commemorated the history of slavery in this urban space. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, it highlights how awareness of slavery amongst direct descendants of enslaved people often figured in efforts to resist increasing racial segregation. The upheaval created by forced removals under apartheid obliterated much of this engagement with the slave past, contributing to a situation in post-1994 South Africa where the urban spaces previously inhabited by the enslaved had fallen silent. More recent representations of slavery by museums, private enterprises, and heritage bodies in the post-apartheid era have sometimes been at odds with the interpretation of slavery held by people identifying as slave descendants who may live with the legacies of apartheid-era forced removals and segregation. The article reveals both the post-slavery experiences of communities who descend from the enslaved and offers insights into how slavery has been remembered in Cape Town over time. The city will be posited as a contested space in terms of discourses surrounding its extensive history of enslavement and colonialism. In doing this, the paper reinforces the idea that the afterlives of slavery in urban areas correspond with the evolving subjectivities of the groups and individuals who perform acts of remembrance.Footnote 3

SLAVERY AT THE CAPE

Slavery at the Cape differed in style from most other systems of enslavement involving Europeans and Africans. Rather than serving as a source of African labour, the Cape was the recipient of enslaved people from Dutch Batavia – in modern-day South East Asia – as well as from elsewhere in Africa, predominantly Madagascar and Mozambique. The desire to import human beings to service colonial society arose from the Dutch East India Company's refusal to permit the enslavement of indigenous Khoi people, although such people were widely used as contract labourers.Footnote 4 Roughly 60,000 enslaved people were either imported to or were born at the Cape between 1658 and 1834, and at various times their number marginally outnumbered that of the colonists.Footnote 5 These people did not work on plantations, but provided heavy labour in the rural wine farming regions, domestic service in settler households, general labour for the government in urban areas, and artisanal work catching fish or manufacturing furniture. The Dutch administration's Slave Lodge in Cape Town was by far the largest single holding of enslaved people, with a population numbering around 1,000 by 1770.Footnote 6 Throughout much of the colony, a pattern of small-scale households enslaving a handful of people was maintained.Footnote 7

The second British occupation of 1806 coincided with waves of domestic abolitionism, and one year later the country outlawed its slave trade. Slavery remained legal at the Cape until emancipation on 1 December 1834, however the value of the freedom achieved by the formerly enslaved was questionable. Facing the prospect of drifting into urban poverty or homelessness, the safest option for a sizeable percentage of the newly liberated was to remain as waged labourers for their former masters by providing a definition of “servant” and circumscribing the rights of such people. The master–slave relationship was effectively perpetuated, aided by measures such as the 1841 Masters & Servants Ordinance, which solidified the balance of power with the former. For Nigel Worden and Clifton Crais, this legislation formed part of a “connective historical tissue” that linked the economic subordination associated with enslavement with attempts at controlling cheap black labour through the colonial, industrial, and apartheid eras.Footnote 8 Additionally, a source of exploitative labour for colonists in the immediate post-slavery period was supplied by several thousand “liberated Africans” who arrived at the Cape off condemned slave ships. These people were indentured for periods of up to fourteen years from the 1810s onwards, with the migration stream ebbing and flowing until the 1860s.Footnote 9

Society at the Cape became more stratified along racial lines as the Victorian period matured.Footnote 10 In Cape Town, burgeoning racial segregation was particularly targeted at inner-city working-class neighbourhoods in response to public health fears.Footnote 11 Many of the formerly enslaved and their descendants lived in these racially mixed areas. They formed a constituent part of a “race” increasingly labelled “coloured” by the state.Footnote 12 This was effectively an all-encompassing label applied to anyone who was neither designated white, nor native black African. In contemporary South Africa it is a contested term, though it remains common language, used both to self-identify and in official documents such as census records.Footnote 13 Though racial segregation was initially targeted at so-called natives, many slave descendants were effectively confined to unskilled, low-paid work in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, lacking the economic means to access skilled training and meet necessary licencing terms.Footnote 14 Segregationist policies were increasingly introduced as the twentieth century progressed, culminating with the introduction of the Afrikaner nationalist system of apartheid in the then postcolonial South Africa in 1948. This resulted in the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of black and coloured people across the country into racially segregated townships under the auspices of the Group Areas Act, first introduced in 1950. It was shortly followed by the formal disenfranchisement for coloured people.

URBAN CULTURE AND MEMORY OF SLAVERY

Evidence that explicitly recalls the existence of enslaved people at the Cape has never been available in any great volume. The kind of memory objects such as shackles and yokes that have helped to define memory of transatlantic slavery are almost entirely lacking in relation to Cape slavery. Enslaved people are instead recalled through customs such as eastern-influenced cuisine, naming patterns among the city's population, and urban built spaces such as Cape Town's Greenmarket Square where a busy market that continues to function today saw the enslaved purchase produce for their masters. As will be discussed, activists over time have contended that socio-economic dislocation experienced by coloured people is an additional tangible legacy of slavery. Although records documenting the first-person perspectives of enslaved people and their immediate descendants in Cape Town are scarce in number, academics have attempted to probe the social environment of the inner-city melting pot in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Existing scholarship enables an understanding of how enslaved people and their descendants negotiated the post-emancipation city and interacted with its diverse inhabitants. The work of Andrew Bank suggests that there existed not so much a culture forged by slavery among urbanized coloured people in the century between emancipation and apartheid, but a working-class culture that transcended racial lines and was bound by the everyday experience of work and survival.Footnote 15 Bank posits the experience of enslavement as an important element of this creolized urban culture given that it grew out of an eastern-influenced slave society that existed in the public meeting spaces and kitchens of Cape Town between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 16 Additionally, Vivian Bickford-Smith has identified how the most visible part of this culture that directly recalled slavery was the annual Emancipation Day celebrations on 1 December, which commemorated the coming of freedom in 1834.Footnote 17 These events included picnics, midnight celebrations, and excursions to the countryside.Footnote 18

A second distinctive element of this culture that demonstrated an awareness of slave roots were the political organizations that emerged among predominantly coloured people during the late nineteenth century to contest burgeoning racial segregation.Footnote 19 These political claims were frequently voiced at events marking Emancipation Day at the turn of the century. During the early 1900s, coloured educationist John Tobin began a regular series of meetings in the District Six area of Cape Town. Based around contesting the idea of white hegemony, black consciousness formed a core component of these group meetings that soon incorporated commemorating Emancipation Day as part of their activist agenda.Footnote 20 At this point, it is perhaps useful to recall Paul Gilroy's idea of political culture as a form of slave memory in his seminal work on the black Atlantic. Gilroy suggested that slavery in North America nurtured a dissonant political culture that has been maintained over time among black people in the transatlantic world and is mobilized in order to question power structures.Footnote 21 Although Pumla Gqola has critiqued the way in which she claims Gilroy homogenizes the pre-slavery experience and argues that this reduces the utility of his work in terms of understanding the creolization that occurred as a product of slavery in South Africa, his thoughts on post-slavery are arguably still relevant.Footnote 22 They are suggestive of a sense of overcoming slavery and of using this to stake claims in the contemporary world and safeguard against returning to a slave-like state. These links are worthy of attention in the South African context, much as they have been commonly associated with African American people.

The validity of these links was demonstrated in events marking the centenary of abolition in 1934 and the centenary of the ending of the apprenticeship period in 1938. Here, political comment infused the celebrations with greater contemporary utility. A 1938 Emancipation Day mass meeting on the Grand Parade saw various trade union and workers’ representatives link slavery with the growing racist agenda of the time.Footnote 23 While this was not the only platform available for such figures, it demonstrates how memory and perceptions of the slave past held utility as a means of mobilizing against an increasingly segregationist state. Although commemorations led by the state and the moderate reformist African People's Organization took a predominantly religious character with homage paid to Christian European abolitionists, the Grand Parade event hints at how some people of slave descent perceived their post-emancipation fortunes in less positive terms.Footnote 24 Racial segregation and apartheid were not direct continuations of slavery, but similarities were evident. Although Cape slavery was not strictly biracial, the balance of power under both systems was such that it benefited the white minority population in material and social terms.

This tendency to evoke the iconography of slavery as a means of contesting political voice in the urban space of Cape Town did, however, faded as the onset of apartheid loomed. The far-left, non-racialist organization, the Non-European Unity Movement – founded in 1943 – continued to associate slavery with all forms of colonial conquest, capitalism, and racial segregation into the 1950s.Footnote 25 From the early 1960s, however, anti-apartheid organizations including the Unity Movement increasingly espoused ideals of black consciousness. Presenting a united front, activists rejected the separatist idea of coloured and black imposed by state racial categorization.Footnote 26 Accordingly, this prompted the end of using slavery as a metaphor and rallying point for coloured opponents of racial segregation.Footnote 27 Rather than looking to lineages such as slavery as a source of inspiration for contesting the segregationist present, a united front against racial persecution was presented by the victims of National Party legislation.

The white minority state, for its part, was also disinterested in histories such as slavery. Mirroring state-led commemorations of the centenary of abolition during the 1930s, National Party recognition of the past tended to obscure the history of slavery in order to buttress representations of settler hegemony. The state-led Cape Town celebrations of the 1952 tercentenary of Jan van Riebeeck's arrival at the Cape incorporated the experiences of coloured people through the lens of the exoticized “Malay” stereotype constructed by the commissioner for coloured affairs, I.D. du Plessis.Footnote 28 The term “Malay” had become synonymous for “Muslim” by the 1850s, referring primarily to the Muslim population living in Cape Town and the wider area, which could trace its origins variously to slaves and princely Indonesian political prisoners.Footnote 29 Owing perhaps to the way in which Islam was forbidden until the early nineteenth century and practised in secret, the Muslim community was somewhat distinct from the urban working-class settlements in which many slave descendants lived in the century following emancipation.Footnote 30 “Malay”, however, was the extent of the apartheid regime's engagement with slavery, and du Plessis's attempts to construct a Malay identity downplayed the topic as an ancestral lineage to focus instead on princely origins, exotic cookery, dance rituals, and delicate physical features.Footnote 31 Official commemoration of the past in Cape Town's public spaces under apartheid was consequently directed away from recognizing the contributions made by enslaved people to forging the contemporary city.

The combined influences of state-imposed racial categories and opposition to these policies in the form of black consciousness resulted in a move away from earlier forms of remembering slavery among slave descendants in Cape Town. Indeed, it is only thanks to revisionist scholarship led by academics such as Mohamed Adhikari in the post-apartheid period that the idea of self-defined coloured identity under apartheid has become apparent.Footnote 32 Within this body of work, it has been suggested that the forging of a pan-African oppositional front to apartheid between coloured and black activists was an act limited to small numbers of coloured community leaders, with the majority of people continuing to live their lives defined by race.Footnote 33 Commenting on oral history work, Henry Trotter has suggested that apartheid and the trauma of forced displacement led to the creation of an alternative coloured metanarrative that emphasized the harmony of pre-Group Areas Act life. Through reminiscences, this rewriting of history offered people a means of coping with the often dangerous and dispiriting conditions in racially segregated townships on the Cape Flats where gang violence and drug abuse remain a feature of life today.Footnote 34 While this narrative offers evidence that coloured people developed their own identities under apartheid, this new self-generated version of the past ignored ancestral origins such as slavery much as did du Plessis's Malay identity construct. This process of memory displacement was not necessarily limited to people who suffered forced removals and also occurred in rural areas of the Western Cape where unequal access to resources has maintained a strict labour hierarchy over the centuries.Footnote 35

AN INCLUSIVE CITY? REIMAGINING THE SLAVE PAST IN POST-APARTHEID CAPE TOWN

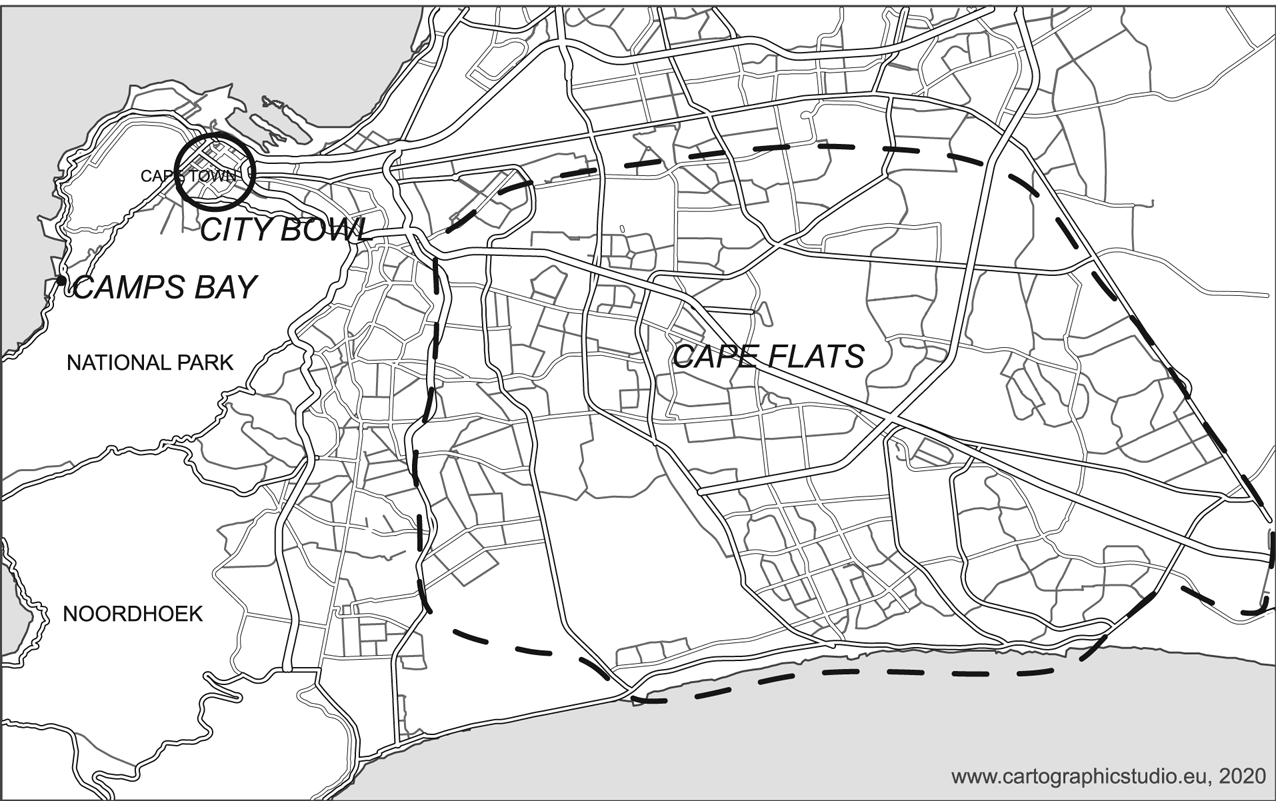

Present-day Cape Town is a city of great contrasts; a place where decades of formal racial segregation continue to influence where people live, work, and how they interact with the city space. Rudimentary shack housing in certain townships, informal settlements, and widespread homelessness stand in stark difference to the sleek towers of the central business district. Put bluntly, there is a far greater chance of being poor if you or your descendants were classified as black or coloured under apartheid than there is of occupying the same status if from a white family. The legacies of Group Areas forced removals are still evident in townships, which largely remain de facto racially segregated, and many black or coloured people experience the city as part of a daily process of commuting in the morning from non-central locations into the city to perform low-wage jobs before reversing the process in the evening. The centre of Cape Town and its immediate residential areas can be accurately described as exclusive spaces, where home ownership is restricted to all but the most affluent clients (Figure 1). The City of Cape Town municipality has actively sought to attract international investment to the central City Bowl, and has supported pledges of capital by implementing a number of City Improvement Districts that “tidy” areas using money raised in taxes levied against businesses. Courting this global investment has been cited as one of the main drivers of gentrification in contemporary Cape Town.Footnote 36 As much as Cape Town is now posited as an inclusive city, the resettlement of poorer residents from social housing to make way for developments has been portrayed as a perpetuation of apartheid-era forced removals by campaigners.Footnote 37

Figure 1. Map showing Cape Town including Cape Flats, City Bowl, and Camps Bay.

The way in which private enterprise has often approached Cape Town's uncomfortable history of slavery has been frequently problematic, too. As Hall and Bombardella have explained, Cape Town redevelopment projects including the GrandWest Casino and Entertainment World, and Century City shopping centre are interested in the past only for the extent to which it can complement commercial activities. Elements of the past such as Cape Dutch architecture are selectively integrated into these developments in an attempt to evoke nostalgia and little else among customers.Footnote 38 Nigel Worden's work on the V&A Waterfront and its historical interpretation panels too demonstrates how the interests of business often work to obscure an open discussion of the past in Cape Town. For Worden, the Waterfront downplays the historical role of the harbour area as a site of enslavement, imprisonment, and working-class labour to portray a city at one with its dock area and thus posit its current role as a shopping and entertainment centre as an extension of this harmony to the present.Footnote 39 There seems to be little space for integrating difficult histories into commercially orientated redevelopments of the supposedly inclusive city that is Cape Town.

Although the egalitarianism of the immediate post-1994 period has faded in part through protests over service delivery, allegations of state-level corruption, and, arguably, a society that neoliberal economics have increasingly stratified along class lines, the democratic era has nonetheless provided fresh opportunities to explore identities among city dwellers. These questions are particularly pertinent for people – including slave descendants – who were classified as coloured under apartheid and the less formal segregation that preceded it. This was a category defined as being between two extremes, a catch-all term for people who were deemed neither white nor black. As a classification, it was premised upon the idea of being forged by racial mixture rather than an easily identifiable source of ancestry; on the idea of not adhering to binaries. The question of coloured identity has been a source of self-exploration for some in the post-apartheid era, although there has been something of a reluctance among coloured people to engage with the ideas of the African National Congress (ANC) state. There has typically been a fear among working-class coloured people that the “new” dispensation is more concerned with furthering the interests of people classified as black under apartheid than with coloured people, and that affirmative action policies are consequently more likely to benefit the former group.Footnote 40 These fears culminated in a vote for the National Party – the party that instituted apartheid – in the 1994 democratic elections among the Western Cape coloured electorate. Literary scholar Zoe Wicomb has argued that this defensive separatism arises from a sense of shame that has dominated the coloured outlook. For Wicomb, shame has been conditioned by the way in which coloured people were subjugated under slavery and consequently told they were inferior to white people by colonial and apartheid regimes.Footnote 41 This shame has manifested itself in various ways, from attempting to claim European lineage under apartheid to engineering distance from black people.

State policy in post-1994 South Africa has stressed the need to transform all areas of the country influenced by the legacies of apartheid-era racial segregation. This ranges from service distribution and residential patterns to employment practices and access to education. The idea of a shared national past has been an important component of attempts to create national cohesion, and has formed the centrepiece of the ANC's arts, culture, and heritage policies from 1994 onwards.Footnote 42 In spite of this agenda, sections of the post-apartheid ANC state have themselves not always been enthusiastic about what are perceived as coloured histories. Slavery has been one of these, and was viewed as a separatist threat to attempts to promote a shared national history that would buttress reconciliation attempts by some officials involved in meetings to open a Cape chapter of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization's global Slave Routes Project during the late 1990s.Footnote 43 Although then deputy president and future president Thabo Mbeki's 1996 “I Am an African” speech offered a broad definition of what it meant to belong to not only South Africa but to the wider continent, the interpretation of history often promoted by the ANC has tended to occupy a more narrow terrain. Opposition to apartheid, and particularly male-dominated political agitation, has been promoted as a unitary, shared history, with the new South Africa forged as a nation that overcame oppression. Earlier human rights violations such as slavery and others conducted under colonialism have been relatively marginalized. The way in which the former prison complex on Robben Island was reopened as a museum in the late 1990s is emblematic of these tendencies. Posited as a site depicting the “triumph of the human spirit over suffering and hardship”, the interpretation of the past offered on the site is a relatively narrow glimpse into the island's post-1960 use as a political prison.Footnote 44 Both the neglect of a centuries-old history of use as a site of exile and imprisonment, and a tendency to privilege ANC opposition to apartheid at the expense of other groups, have been noted as criticisms.Footnote 45 The sense that this can bypass coloured ancestral histories such as slavery builds upon claims in some quarters that the ANC is not interested in coloured people.

The work of small numbers of dedicated activists and museologists, as well as the idea that national reconciliation has lost currency as time has passed, has ensured that slavery is at least discussed by heritage spaces in Cape Town's urban centre. Wicomb's thoughts on shame effectively amounted to a call to embrace coloured identity as distinctive but simultaneously part of a wider black politics. Operating within the theoretical egalitarianism encouraged by the post-apartheid state, other coloured intellectuals have also called for people to redefine the meaning of “coloured”, liberating it from its origins as a white supremacist imposition.Footnote 46 Independent of these debates, there has been a renewed focus in public discourse on the impact of colonialism on South Africa in recent years. In 2015, a student protest movement titled #RhodesMustFall identified the statue of the arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town's Upper Campus as representative of prevailing white privilege and a number of other inequalities in contemporary South African society. Taking Rhodes as an example of an individual who introduced lasting patterns of violence and trauma to South Africa, the students successfully campaigned for the removal of the statue. This protest movement precluded debates regarding decolonization that, though chiefly originating with the South African student population and targeted at the university sector, have extended to critiques of wider society. By design, such a discourse focuses on the salience of colonialism and how its influences continue to shape society today. There is a sense from these debates that the post-apartheid ANC state has not openly discussed these issues, with the landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission primarily orientated towards enabling people to come to terms with lived human rights abuses. While community leaders are redefining identities in relation to racial categories imposed under colonialism and apartheid, there is a definite sense that broader society is gaining awareness of the more distant past.

Quite what resonance discourses surrounding identity and the colonial past have with working-class people is questionable; however, it would be fair to suggest that community leaders are very much part of the debates.Footnote 47 Identification as Khoisan has become relatively popular, enabling not only an alternative identity to coloured, but also allowing actors to contest first-nation people status previously limited to Bantu-speaking Africans.Footnote 48 Though less widely recognized, acknowledgement of slave ancestry has also become increasingly evident.Footnote 49 For some people, this involves identifying with ancestors who fought against slavocratic hegemony as a source of pride and guidance.Footnote 50 Accordingly, Adhikari has defined the present as a “third paradigm” in coloured identity politics; an era of “social constructivism” in which coloured identity is recognized as self-defined and reworked as such.Footnote 51

Where slavery has been recalled by post-apartheid museological projects in Cape Town (Figure 2) it has not always been on harmonious terms with how coloured slave descendants view their ancestral histories. While enslavement has different meanings on a global scale, it is also understood differently on a much more local level, and contestations have frequently occurred in Cape Town over the representation of this past. The case of the Slave Lodge, a distinctive feature of Cape Town's built environment, demonstrates this point. Dating from 1679, the Slave Lodge is the second oldest building in Cape Town after the Castle of Good Hope, making it one of the oldest in South Africa. After the Cape became a British colony, use of the Lodge as slave quarters was gradually scaled back, and passed through various uses including as government offices, as a post office, and perhaps most famously as the Supreme Court building.Footnote 52 It entered its current phase in 1966 when it opened as the South Africa Cultural History Museum (SACHM), a satellite site of the South African Museum and its natural history exhibitions.Footnote 53 Typical of apartheid-era museum displays, little reference was made to the lives of marginalized people in a museum that instead exhibited collections of Greek vases, Roman archaeology, Tibetan weaponry, and South African stamps.Footnote 54 Reflecting moves towards more inclusive representations of the past, the museum was renamed Slave Lodge in 1998, and thus theoretically was reconnected with its historical role as a site of confinement (Figure 3). It was shortly afterwards one of a number of state-funded museums grouped under the new southern state “flagship” museum management organization, Iziko Museums.Footnote 55

Figure 2. Map showing sites of slave memory in Cape Town's City Bowl.

Figure 3. The exterior of the Slave Lodge, 2015.

This symbolic name change did not immediately herald any revisions to displays, and the museum's displays remain a visible legacy of apartheid, even today. While the ground floor has been redeveloped to host a permanent slavery exhibition and various temporary exhibitions with a human rights focus, much of the building's first floor continues to display apartheid-era SACHM exhibitions. In this sense, the Slave Lodge is almost a “meta-museum”; defining a space that tells us as much about the museological practices of the apartheid era as it does about Cape slavery. Current staff are well aware of these issues, although it has been suggested that its present form offers a useful case study of post-apartheid transformation and its limitations.Footnote 56 Various reasons including a prevailing institutional preoccupation with artefacts and funding deficiencies have been cited as factors that have stymied change.Footnote 57 Identity politics may have played a longer-term role, as some perceived the state to view the history of slavery as divisive during the late 1990s and early 2000s, a time when reconciliation was on the national agenda.Footnote 58 Consequently, governmental investment in new exhibitions at the Slave Lodge was not readily forthcoming.

Eventually, South Africa's first museum exhibition dedicated purely to Cape slavery opened in 2006 in the southern ground floor wing of the Slave Lodge. The Remembering Slavery exhibition offers a contextual background that makes clear to the visitor the context of Cape slavery in the Indian Ocean trading world, the origins of the people enslaved at the Cape, and the history of the Slave Lodge. Although one feature titled “Column of Light” (Figure 4) displays the names of some of the people who were forcibly confined in the Slave Lodge, content exploring individual stories and human agency are relatively scarce. Part of this owes to the absence in South Africa of the kind of first-person narratives that characterize the retelling of transatlantic slavery. Simultaneously, the curatorial decision to depict the rebellion leaders on the VOC slave ship Meermin as “mutineers” raises questions as to whose perspective the Remembering Slavery exhibition advocates.Footnote 59 There is also a general lack of artefacts in the exhibition, reflecting how any relevant objects were not viewed as a priority for preservation by successive white supremacist regimes. As such, recreations take centre stage, including a mock-up slave ship hold and a simulation of life in the historic Slave Lodge.

Figure 4. The “Column of Light”, 2015.

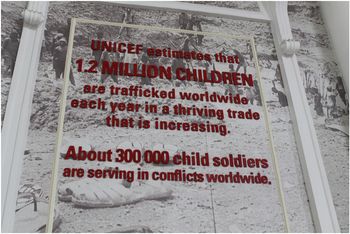

Perhaps reflecting the perception held by some at the turn of the century that slavery was a divisive history, issues pertaining to coloured identity are almost entirely negated by the Remembering Slavery exhibition. Instead, Cape slavery is packaged within a reconciliatory discourse that posits it as a lesson both for South Africans and humanity. In this sense, Remembering Slavery shares many characteristics with what Paul Williams has identified as the “memorial museum”. Williams explains a tendency for sites that commemorate notable atrocities to posit “their” atrocity as a lesson for humanity, along the lines of inviting visitors to pledge “never again”.Footnote 60 He problematizes the way he claims that this universalizing narrative can in fact obscure the gravity of the event that the museum primarily is intended to commemorate.Footnote 61 At the Slave Lodge, the evocation of this human rights discourse borrows both from global patterns of thought and from national efforts to posit common histories as a means of supporting post-apartheid reconciliation work. The opening of Remembering Slavery saw the Slave Lodge rebranded as a space with the motif, “human wrongs to human rights”. The foyer area of the Slave Lodge informs the visitor that slavery “continues to exist in different forms” before offering statistics showing the number of people enslaved globally today (Figure 5). Other sections of the building that have been redeveloped host temporary exhibitions focusing on various elements of the anti-apartheid campaign. This is suggestive of a space that aims to portray a range of South African human rights abuses, and depict a nation that has overcome a challenging past.Footnote 62 In this sense, the discourse of national reconciliation that characterized the ANC's initial post-apartheid arts and culture policies is an evident influence in the exhibition.

Figure 5. Displays in the foyer area of the Slave Lodge, 2015.

In presenting a critical examination of the narrative on display at Elmina Castle in Ghana, Ana Lucia Araujo suggests that evoking a generalized human rights discourse in a slavery museum can marginalize the often fraught post-slavery experience of many slave descendants.Footnote 63 In the case of Elmina, compared with international visitors to the site, the local population lives in relative poverty, which can be partially attributed to the legacies of slavery and is visible to anyone visiting the castle.Footnote 64 Similar comments could be aimed at the Slave Lodge. Although – galvanized by the discovery of the wreck of the slaver São José off Camps Bay in 2015 – work is now underway to engage with communities who descend from enslaved people in Cape Town, the permanent displays at the Slave Lodge have typically been silent on issues of identity and legacy in the city. In contrast to Elmina, slavery's legacies are perhaps not quite so visible in Cape Town. The majority of the city's poorer residents continue to live in apartheid-era townships away from the city centre. These residential areas remain largely racially exclusive and are blighted by social problems, particularly gangsterism and substance abuse. Though connecting modern social problems with slavery is a fraught process, it would be fair to suggest that the descendants of people who were enslaved later experienced racial segregation and forced removal and currently form the backbone of Cape Town's labour force. Slavery's legacies arguably manifest in labour organization and access to socio-economic resources today. The visibility of these effects may have been removed from the city centre, but they continue to shape the city itself. A narrative that posits a glorious present in the way reconciliation discourse in South Africa has done marginalizes the ongoing dislocation experienced by many South Africans. In this sense, people are potentially further alienated, rather than brought together in commonality as intended. Numerous conclusions can be drawn from this point. First, the weaknesses of national metanarratives in terms of facilitating discussion of the past are revealed. The possibility of slavery ever functioning as part of such a narrative is highlighted, as are the problems inherent in trying to provide closure on the past when its legacies still figure in the lives of the people effected.

This tension between Cape Town's slave past, the everyday lives of slave descendants, and differing approaches to slavery as an identity issue was revealed in visceral terms by debates raised by excavations in the Prestwich Street area in the 2000s. In 2003 developer Ari Estathiou of Styleprops Ltd stumbled across human remains while laying the foundations for an exclusive apartment development in the Green Point area of Cape Town. The presence of similar unmarked gravesites for Cape Town's marginalized classes dating from the Dutch and British colonial eras is well known to academics.Footnote 65 This was quite literally a case of the dead and their memories resurfacing in a society that had largely forgotten them. Following protocol, the developer notified the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), construction was halted, and a public consultation process launched. Two sides of the debate immediately crystalized. On the one hand, a predominantly coloured group of people organizing as the Hands-Off Prestwich Street Ad Hoc Committee objected to both the development and potential exhumation of the human remains, having identified them as belonging to their enslaved ancestors. Opposing these activists were a group comprised of academics – including archaeologists and human biologists – who, tacitly supported by SAHRA, supported the exhumation of the bones on the grounds of the unprecedented opportunities the discovery presented for furthering knowledge of a period of time largely understood through the colonial documentary archive.Footnote 66 Following an emotive and charged campaign, the development was permitted to proceed and the bones exhumed, although biological testing has been forbidden and access restricted via an application process including a panel comprising campaigners from both sides of the argument.Footnote 67 At the time of writing, no research applications have been accepted.

As Shepherd and Ernsten argue, the exhumation debate reflected who does and does not have access to power and voice in post-apartheid South Africa.Footnote 68 While the issue of exhumation was being contested, there was a sense of an emotive connection with assumed ancestors colliding with the regulations and management speak of the new elite. Running throughout was a sense that local government officials and coloured identity activists did not share the same interpretation of the slave past, with the former misunderstanding its importance to small, vocal groups of people. These themes again moved to the forefront with the opening of coffee shop Truth on the grounds of the Prestwich Memorial, and their recurrence is probably the result of ignorance towards slavery and the way in which it has been disremembered over time. Although members of the PPPC had been involved in the constructive dialogical process behind the original opening of the memorial, the City of Cape Town municipality failed to consult with them before accepting Donde's proposal.Footnote 69 They had approved plans originally circulated prior to the memorial's opening for some form of small-scale tea kiosk, but argued that the scale of the Truth cafe surpassed this.Footnote 70 It is difficult to disagree with this point. The presence of Truth gives the memorial building a coffee shop ambience, with the rattle of cutlery, scraping of chair legs across the floor, and filling of coffee cups dominating the soundscape. Menus for the coffee shop have even been placed among the interpretive panels, and there is a sense that the visitor must request permission to proceed to the memorial area from Truth staff.

The way in which Truth conceives its connection to the Prestwich Memorial (Figures 6 and 7) serves to reinforce perceptions of exclusivity and restricted voice. Though now replaced with a revised design that makes no reference to the memorial, Truth's website at one stage included astoundingly crass claims to how “a growing number of Cape Town locals, tourists and coffee aficionados have unwittingly been lured to this undercover burial ground. And been given a taste [of] how good slavery can be […] (To artisan coffee of course, in this case!)”.Footnote 71 It referred not to a complex and contested history, but carelessly described the human remains interred in the same building as “skeletons in our closet”. This light-hearted and disrespectful attitude to the past serves to appropriate what is for some a personal and emotive history for commercial gain. It is useful here to note M. Christine Boyer's incisive analysis of city planning. Boyer argues that, in redeveloping urban areas, middle-class professionals subscribe to the concept of a universal “community”, eschewing the possibility that not every resident of the city holds the means to access and participate in what often becomes a process of gentrification.Footnote 72 This process played out at Prestwich. Largely removed from city centre residence by apartheid-era racial segregation and excluded from returning by high property prices in prime locations, slave descendants have been refused a stake in the memorialization process by the same forces of gentrification and an assumption that everyone has equal access to resources in post-apartheid South Africa. Much like representations of slavery at the Slave Lodge, this approach to the past posits slavery as a universal history. The terms by which it does it, however, are different. They originate not from a fundamental subscription – however justifiable in reality – to using the past to encourage positive change, but from a sense that history is malleable for commercial gain, with its specificities expendable on the grounds that the past is a distant place with scant resonance among contemporary Capetonians. The remnants of slavery in the form of its unnamed dead become linked with its legacies in the continued marginalization of slave descendants in Cape Town's public sphere today. Working-class Capetonians are excluded from gentrified spaces on economic grounds, and there is a sense that their concerns are not taken on board by municipality bureaucrats. As with the Remembering Slavery exhibition at the Slave Lodge, the possibility of slavery functioning in the tapestry of identities that form modern Cape Town is marginalized, as is the significance of this history to groups of activists.

Figure 6. The exterior of the Prestwich Memorial, 2015.

Figure 7. The interior of the Prestwich Memorial, ossuary area behind the black gate, 2015.

Evidence drawn from the contestations surrounding Prestwich and recent developments at the Slave Lodge do however point towards the possibility of slavery being embraced as an ancestral identity in Cape Town. The rediscovery of the remains of the Portuguese slaver São José off the coast of Camps Bay in 2015 by a team led by members of Iziko's maritime archaeology unit has heralded new possibilities for the museum's future.Footnote 73 Although a number of the artefacts recovered have been loaned to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, which part-funded the project, a portion were retained in Cape Town for an exhibition that opened in December 2018. The artefacts include copper fastenings and ballast items and represent not only rare examples of items preserved from a slave ship, but also the kind of tangible links with the slave past that are widely absent from Cape Town. Iziko organized a number of public events – beginning with a June 2015 symposium titled “Bringing the São José into Memory” – with the aim of reaching a consensus as to how to display the artefacts and communicate their significance. At an event in April 2016, community representatives and staff discussed ancestral links with Mozambique.Footnote 74 This highlights how the São José rediscovery has not only galvanized a more outward-facing approach at Iziko, but has also encouraged people to consider where slavery fits in to their lineage.

This change of approach at Iziko and more open discussion of slavery and its legacies sit within a broader context of an increased focus on the more distant past. In successfully campaigning for the removal of the Rhodes statue, the student activists who formed #RhodesMustFall in 2015 suggested that colonial-era injustices require discussion to enable South Africa to come to terms with its role in establishing patterns of socio-economic inequality that persist in the present. In a nation that used the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to come to terms with apartheid, longer-term systemic issues have perhaps been marginalized. The way historical slavery has been viewed by various branches of government and museum professionals is a strong example of this. Not only was it frequently ignored, but the way that the Prestwich consultation was carried out and the narrative voice adopted in Remembering Slavery seemed to deny its relevance to questions of identity. While the example of the Truth coffee shop suggests that there is still distance to be travelled before this significance is universally understood, the open approach Iziko has taken to the São José artefacts points towards an interpretation of slavery that reconnects urban Capetonians with its impact on the contemporary city and its inhabitants. Developing these themes, a temporary exhibition titled My Naam is Februarie: Identities Rooted in Slavery opened at the Slave Lodge in October 2016. Based on the idea of a calendar designed by the marketing company Geometry Global whose creative director approached Iziko with the belief that the Cape's slave heritage warranted greater discussion, the exhibition matched each month of the year with the surname of a participant. John January represented January, Felix February for February, and so forth, with obvious links to slave naming patterns at the Cape. An accompanying video featured participants reflecting on this heritage, with several commenting how in the past these links were simply not discussed at family or any other level. Speaking about these previously unspeakable, long-term legacies is a role that a Slave Lodge mindful of the way in which history impacts contemporary residents of Cape Town can play. The previously unspoken legacies of slavery encoded in the city's contemporary population begin to become visible, and slavery gains greater recognition as an ancestry.

The debates generated by Prestwich, and interest in recent museological milestones in the São José rediscovery and the My Naam is Februarie exhibition point towards the sense that identification with slavery is being embraced by descendants of the enslaved in Cape Town. Increasingly, the same activists who object to developments such as Prestwich and question the interpretation of slavery visible at the Slave Lodge are offering their own interpretations of Cape slavery to the public. These representations offer alternative meanings of slavery, identifying the institution as an ancestral history, rather than as a universal lesson for humanity. Although the number of people openly claiming slave ancestry and espousing an identity based around recognition of these roots remains relatively small, these claims have nonetheless increased in volume and acceptance in the 2010s. This perhaps owes itself to efforts by historians of Cape slavery to veritably “reconnect” people with their history by encouraging genealogical enquiries, increased visibility of slavery through public exhibitions such as Remembering Slavery, and people gradually acknowledging calls by coloured community leaders to revaluate how they define themselves. Although Remembering Slavery should be accorded with influence in terms of raising awareness of the history of Cape slavery, it has frequently attracted criticism from people claiming slave ancestry for the way it represents this past. As the Prestwich case highlights, there is frequently a disconnect between how Cape Town's slave past is imagined by people identifying as slave descendants and representations of this past by state-funded heritage projects.

Lucy Campbell is one person who has used the public space created by the heritage industry to contest representations of what she perceives as a personal history. As a coloured woman born under apartheid, Campbell intertwines numerous traumatic histories into the forthright narrative offered on historical walking tours of Cape Town. The name of her company, Transcending History Tours, is indicative of the way she questions the “official” narrative, and urges alternative interpretations of the past that resonate with everyday Capetonians. Her tours seek to illuminate the imprints made by the forgotten history of slavery on the urban landscape and offer a reminder of the disadvantages suffered by many slave descendants today. She is critical of the Slave Lodge, claiming that the Remembering Slavery exhibition fails to speak to communities by negating to engage with the more violent aspects of Cape slavery.Footnote 75 In this sense, the concept of slavery as a traumatic foundational experience that ancestors overcame is similar to the way in which transatlantic slavery has often been remembered by African American people.Footnote 76

Identifying with a broad Khoisan and slave ancestry, Campbell claims to have become enthralled with this past while working in customer service for Iziko at Groot Constantia.Footnote 77 Reading about the lives of people enslaved on the estate gave her a sense of place previously lacking, and motivated her to embark upon what she describes as a therapeutic journey of self-discovery.Footnote 78 It is this therapy-through-history she now aims to facilitate through her walking tours. These tours exist in a competitive heritage market in Cape Town, with numerous other operators offering what are frequently sanitized narratives of reconciliation and post-apartheid prosperity as the logical outcome of a troubled history to international visitors. Although Campbell concedes that the majority of Cape Town's working-class residents are too preoccupied with the daily struggles of life to engage with subversive interpretations of a past that they may not even acknowledge exists, she is still able to act as a willing spokesperson for this group to the non-governmental organizations and academics who provide the bulk of her customers.Footnote 79

A tour in September 2015 involving a mixed-age community group from Tafelsig on the Cape Flats was perhaps an exceptional case. On this occasion, Campbell was able to play the role of facilitator in reconnecting people with a forgotten past. Starting at the Castle of Good Hope – the oldest colonial building in Cape Town – she urged the group to embrace their history as far back as colonial times. This, she explained, would initiate a therapeutic process as it would enable them to better understand the social problems facing their communities today. Throughout the tour, Campbell highlighted various objects of historical interest and reminded the group of the contributions their ancestors made towards constructing modern Cape Town. The way in which this contribution had largely been written out of the cityscape by the selective memorialization of colonial notables figured prominently, and the group appeared to embrace this narrative. At the Castle, for example, one member of the group attempted to claim free entry on the grounds that they descended from the people whose labour constructed the building. The VOC emblems fixed to the pavement of the renamed Krotoa Place were symbolically stamped upon. A mock slave auction was conducted at the former site of the slave tree on Spin Street, with participants asked to visualize what their ancestors suffered in their status as the property of strangers. By the end, the group were chanting “We are slaves! We are San! We are Khoi!” and had pledged to establish their own community history museum in Tafelsig to contest some of the narratives on offer in central Cape Town.

This particular tour evidences how working-class people can take note of calls from community leaders in terms of reconsidering the self. This is one of the primary means by which awareness of slave ancestry is spreading in Cape Town. For the community group, Campbell was not only a tour guide offering an alternative historical narrative but a relatable voice who understood the social problems facing poorer areas of Cape Town having experienced them first-hand herself. This understanding and associated advocacy reveals an additional dimension to how slave memory is resurfacing in post-apartheid South Africa, recalling the claims of political activists during the first half of the nineteenth century. Identifying slavery as an institution that caused suffering for their ancestors, activists such as Campbell compare this experience with the socio-economic lot of Cape Town's poorer communities – and particularly likely slave descendants – today. Understanding this history also enables people to make claims for increased recognition in the present on the grounds of their ancestors’ contribution to shaping history, thus highlighting a parallel with the Khoisan movement and a sense of how claiming a slave ancestry may gain broader traction.Footnote 80 This forms the basis of critiques of post-apartheid society, making it possible to highlight how working-class people remain marginalized in spite of liberations from slavery in 1834 and from apartheid in 1994. While with the group from Tafelsig, Campbell identified the psychological remnants of enslavement among Cape Town's coloured population as manifesting in substance abuse and employment practices.

It is in this sense that memory of slavery in Cape Town can increasingly be thought of as the “living intellectual resource” Gilroy wrote of in the transatlantic sense.Footnote 81 A reimagined narrative of slavery in which ancestors form the basis of a proud and emotive connection with the past is mobilized to critique the present. Criticisms do not only cover socio-economic inequalities, but, as the case of the PPPC demonstrated, can also be applied to the way in which activists perceive the post-1994 state to have marginalized “their” history. Renewed efforts to commemorate 1 December as Emancipation Day over the past decade have frequently adopted this rhetoric. Led primarily by the acclaimed independent District Six Museum, a midnight march on 30 November is currently held on the streets of Cape Town each year, recalling the commemorations led by slave descendants during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This event draws in an increasingly large audience, many of whom come from poorer communities on the Cape Flats. The 2015 event culminated with entertainment in the form of music and dance at the Castle (Figure 8). The Castle's CEO, Calvyn Gilfellan, who has been instrumental in inviting heritage activists to use what was previously considered a colonial space since being appointed in 2013, delivered a short address to the gathered crowd. “Our communities are still enslaved”, he reminded them, with “enslavement” in this sense referring to sexual violence, the debilitating influence of AIDS on poorer communities, and prevailing substance abuse in townships. “Enslavement” here acts as a proxy for the ways in which the past has dictated troubles in present-day South Africa. The communities Gilfellan was addressing were enslaved by the Dutch, enslaved by the racial segregation of the British and apartheid eras, and remain enslaved by injustice now. In evoking this memory, community leaders are actively reconnecting people with history in a way that was popularized by predecessors opposing racial segregation in the early twentieth century.

Figure 8. Participants in the 2015 1 December commemorations gathered at the Castle, Cape Town.

CONCLUSION

Slavery is resurfacing in post-apartheid Cape Town in a number of different ways. Over time, this urban space has been built on slavery, remembered slavery selectively, forgotten it entirely, and now hosts contested claims to its meaning today. Political activists during the early twentieth century frequently used the imagery of slavery as a means of analysing progress towards political freedoms; however, the memorial practices and everyday suffering unleashed by formal racial segregation necessitated the disremembering of this past. The post-apartheid state has focused on coming to terms with the more recent past, often marginalizing the influence of more distant colonial history in the process. It is only in recent years that this past has gained greater public exposure through the efforts of identity activists, museologists, and political activists calling for decolonization. The often highly personalized identification with the slave past evoked by community historians is frequently at odds with the way in which state-funded museums such as the Slave Lodge interpret slavery in more universal terms. Here, the city's past is the basis for a lesson in human rights, with deference both to national discourses of reconciliation and international human rights exhibitions in museums. Elsewhere, Cape Town's history of slavery has clashed with urban redevelopment programmes. In the case of the rediscovered bones in Prestwich and their subsequent memorial, the interests of the municipality, private business, and people who identify as slave descendants were not harmonious. There was a sense here of intergenerational exclusion, from enslavement in the colonial era, racial segregation under apartheid, and exclusion from the post-apartheid order for coloured people. Arguably, the concerns raised by activists claiming slave ancestry require greater attention from all parties concerned if Cape Town is to truly eschew the legacies of enslavement in the post-apartheid era.