No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

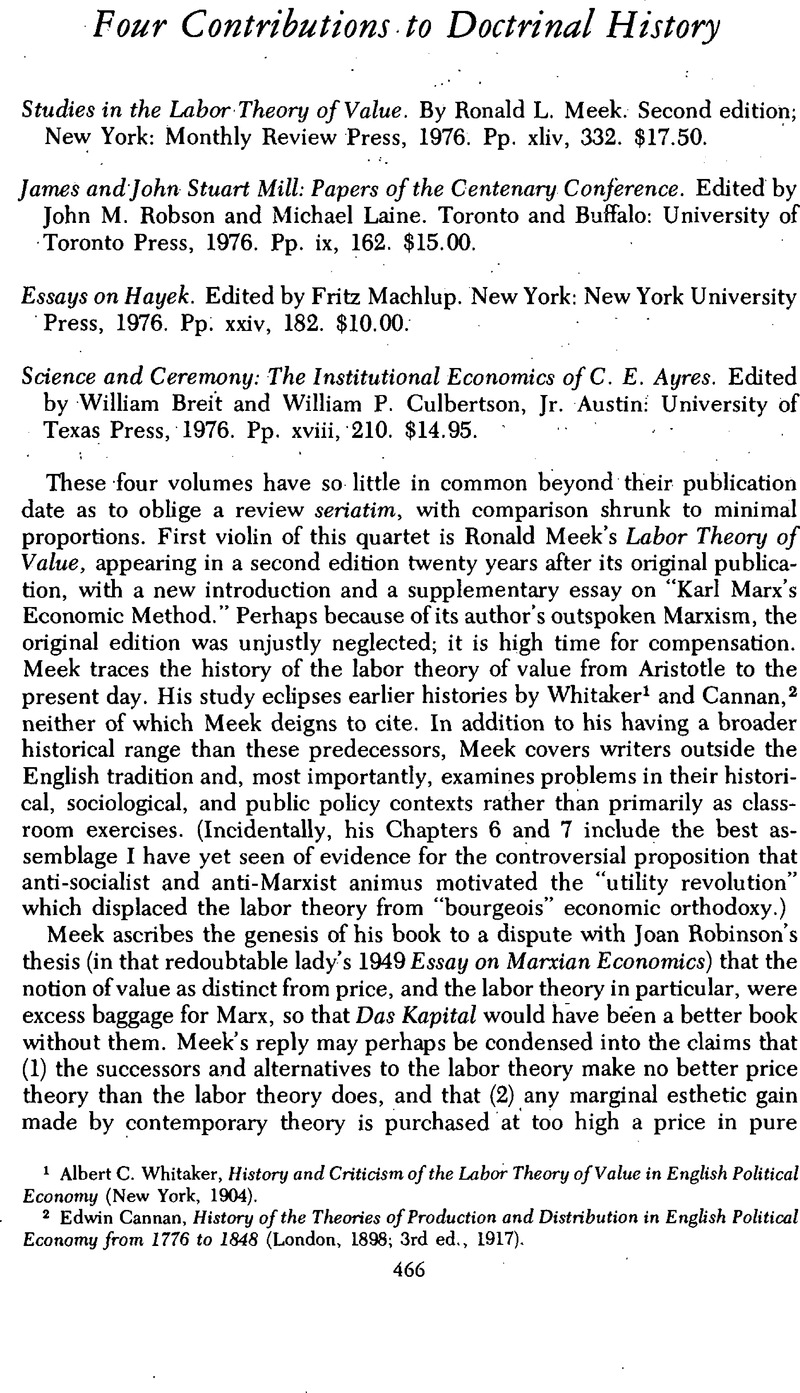

Four Contributions to Doctrinal History

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 May 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Economic History Association 1977

References

1 Whitaker, Albert C., History and Criticism of the Labor Theory of Value in English Political Economy (New York, 1904)Google Scholar.

2 Cannan, Edwin, History of the Theories of Production and Distribution in English Political Economy from 1776 to 1848 (London, 1898; 3rd ed., 1917)Google Scholar.

3 Samuelson, Paul A., “Understanding the Marxian Notion of Exploitation,” Journal of Economic Literature, 9 (June 1971), 399–431Google Scholar. See also Martin Bronfenbrenner, “Samuelson, Marx, and Their Latest Critics,” ibid., 11 (March 1973), 58–63.

4 Morishima, Michio, Marx's Economics: A Dual Theory of Value and Growth (New York and London, 1973)Google Scholar.

5 In addition, Professor J. H. Burns' essay on James Mill's anti-Benthamite concept of “philosophical history” (however badly reflected in the more supercilious passages of the History of British India) and Robson's discussion of the two Mills' views of “human nature” are of peripheral interest to both economists and economic historians.

6 Blaug, Mark, Economic Theory in Retrospect (Homewood, ill., 1962), ch. 4, esp. pp. 81–113, 126–128Google Scholar, summarizing his earlier dissertation, “Ricardian Economics” (New Haven, 1958).

7 For Marx on Mill, see Capital (Kerr ed.), Vol. I, p. 669, n. 1. A more derogatory reference (ibid., vol. Ill, p. 653) was apparently written by Engels.

8 Despite his status as Veblen's intellectual heir, Ayres was never a Veblen student. The two men were located physically close to each other during Ayres' tenure at Amherst College and at the New Republic, but I do not know the extent of their personal acquaintance.

9 This clause, in my view, applies less to Ayres than to many other institutionalists, such as the Commons-inspired group of the “Wisconsin school.”