INTRODUCTION

Right hemisphere damage (RHD) due to stroke is associated with a multitude of cognitive-communication deficits (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Klepousniotou, Scott, Papthanasiou, Coppens and Potagas2017). Many studies have reported that RHD can lead to aprosodia, a disorder in which individuals have difficulties either expressing (expressive aprosodia) or comprehending (receptive aprosodia) prosody (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Baum, Cuddy and Munhall2002; Rinaldi & Pizzamiglio, Reference Rinaldi and Pizzamiglio2006; Ross, Reference Ross, Schacter and Devinsky1997, Reference Ross1981; Ross & Monnot, Reference Ross and Monnot2008; Stockbridge et al., In Press). Prosody refers to manipulations of rhythm, pitch, rate, and volume of speech that speakers use to change the meaning of their utterances. Two forms of prosody that convey information that can alter the intended meaning of the sentence are linguistic and emotional prosody. For example, linguistic prosody can carry information about the syntactic structure of a sentence; indicate whether an utterance is a statement or a question; and help distinguish between the noun versus verb meaning of a word by placing stress on different syllables (e.g., the noun “PREsent” vs. the verb “preSENT”) (Peppé, Reference Peppé2009; Raithel & Hielscher-Fastabend, Reference Raithel and Hielscher-Fastabend2004). Linguistic prosody also conveys pragmatic cues about turn-taking, focus (highlighting a certain aspect of a sentence), and contrast (e.g., “I said his birthday is on MONDAY” where the emphasis on Monday suggests it contrasts with another piece of information). A recent review suggests that there is consistent evidence for the association of RHD with emotional aprosodia, whereas the relationship between RHD and linguistic aprosodia is less clear (Stockbridge et al., In Press). Emotional prosody (also termed affective prosody) conveys the emotion of the speaker. For example, the meaning of the sentence, “I can’t believe you came” can change depending on if the speaker says it with an angry, happy, surprised, or sad inflection. Linguistic prosody conveys information about the grammatical and pragmatic aspects of language (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Dahan and Van Donselaar1997).

In addition to emotional prosody deficits, individuals with RHD may experience difficulty with other forms of emotion recognition and expression, such as deficits in recognizing and producing emotional facial expressions (Blonder et al., Reference Blonder, Heilman, Ketterson, Rosenbek, Raymer, Crosson and Rothi2005; Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Karow et al., Reference Karow, Marquardt and Marshall2001; Kucharska-Pietura et al., Reference Kucharska-Pietura, Phillips, Gernand and David2003) and using fewer than normal emotional words in discourse (Bloom et al., Reference Bloom, Borod, Obler and Gerstman1992; Borod et al., Reference Borod, Rorie, Pick, Bloom, Andelman, Campbell and Sliwinski2000). Researchers have also reported that some individuals with RHD have difficulty comprehending emotional semantic meaning at the word and sentence levels (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002). This impaired emotional comprehension could manifest as difficulty understanding and making inferences about the meanings of emotional words and sentences (e.g., the sentence “After the meeting, he punched the wall” indicates the man is angry). Additional cognitive deficits commonly associated with RHD include attention and executive functioning deficits, which can have an impact on problem solving, reasoning, organization, and insight (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Klepousniotou, Scott, Papthanasiou, Coppens and Potagas2017). Hemispatial neglect and extinction are also frequently reported (Karnath & Rorden, Reference Karnath and Rorden2012; Kenzie et al., Reference Kenzie, Girgulis, Semrau, Findlater, Desai and Dukelow2015; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Saxena, Oishi, Oishi, Walker, Rorden and Hillis2020). Hemispatial neglect is an attentional disorder that reflects inadequate processing of stimuli located in the contralesional side of space. Extinction is characterized by the inability to perceive contralateral stimuli when they are presented together with ipislateral stimuli of the same type (Bonato, Reference Bonato2012). Hemispatial neglect and extinction often co-occur (Bonato, Reference Bonato2012) but not always (Cocchini et al., Reference Cocchini, Cubelli, Della Sala and Beschin1999; Vossel et al., Reference Vossel, Eschenbeck, Weiss, Weidner, Saliger, Karbe and Fink2011). In terms of communication disorders, individuals with RHD often experience difficulties with critical components of communication that rely on higher level language abilities (Blake, Reference Blake2009; Cheang & Pell, Reference Cheang and Pell2006; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Brownell, Jacobs and Gardner1990; Siegal et al., Reference Siegal, Carrington and Radel1996). As a result, they can have difficulty comprehending non-literal language, such as humour or sarcasm (Champagne-Lavau & Joanette, Reference Champagne-Lavau and Joanette2009), and difficulty integrating contextual cues in order to revise initial interpretations (Brownell et al., Reference Brownell, Potter, Bihrle and Gardner1986; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Bloise, Timko and Baumgaertner1994) or determine intended meaning (Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Baumgaertner, Lehman and Fassbinder2000, Reference Tompkins, Blake, Baumgaertner and Fassbinder2001).

While we have an understanding of the kinds of deficits that commonly occur subsequent to right hemisphere stroke, there is a paucity of information about the prevalence, timecourse, and patterns of co-occurrence among these deficits. For the approximately 50% of adults with RHD due to stroke that experience communication deficits, understanding deficit profiles is important for rehabiliation outcomes (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Côté et al., Reference Côté, Payer, Giroux and Joanette2007; Ferré & Joanette, Reference Ferré and Joanette2016). It is estimated that receptive emotional aprosodia will occur in 70% of individuals with right hemisphere stroke during the acute stage of recovery (Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Keator, Breining, Wright, Saxena, Tippett and Hillis2020) and 12–44% during the subacute and chronic stages (Darby, Reference Darby1993; Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Keator, Breining, Wright, Saxena, Tippett and Hillis2020). Documenting the prevalence of receptive linguistic aprosodia subsequent to stroke, regardless of time post onset, has received nominal empirical attention; one study, however found evidence that 29% of individuals would experience receptive linguistic aprosodia at the chronic stage of recovery (Leiva et al., Reference Leiva, Difalcis, López, Micciulli, Abusamra and Ferreres2017). Despite the importance of prosody to receptive and expressive communication, there are no estimates of the percentage of stroke patients with expressive emotional aprosodia at any recovery stage. In fact, hemispatial neglect is the only other disorder for which there are estimates of prevalence and recovery for individuals with RHD; estimates range from approximately 35 to 70% during acute and early subacute stages (Gillen et al., Reference Gillen, Tennen and McKee2005; Ringman et al., Reference Ringman, Saver, Woolson, Clarke and Adams2004; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Wilson, Wroot, Halligan, Lange, Marshall and Greenwood1991; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Saxena, Oishi, Oishi, Walker, Rorden and Hillis2020), and from 14 to 37% during the chronic stage (Karnath et al., Reference Karnath, Rennig, Johannsen and Rorden2011; Lunven et al., Reference Lunven, Thiebaut de Schotten, Bourlon, Duret, Migliaccio, Rode and Bartolomeo2015; Nijboer et al., Reference Nijboer, Kollen and Kwakkel2013). Factors such as stage of recovery, lesion size, and location within the right hemisphere likely impact the occurrence of communication deficits, but to date there is minimal evidence to support strong conclusions.

For stroke patients, it is important to consider time since stroke onset when evaluating research studies (Hillis & Tippett, Reference Hillis and Tippett2014). That is, following a stroke, individuals will often experience some degree of dynamic reorganization of language and cognitive networks during which undamaged areas of the brain take over some functions from damaged areas. Thus, deficits that are apparent during the acute stage of recovery may resolve or lessen in severity by the chronic recovery stage (El Hachioui et al., Reference El Hachioui, Lingsma, van de Sandt-Koenderman, Dippel, Koudstaal and Visch-Brink2013; Maas et al., Reference Maas, Lev, Ay, Singhal, Greer, Smith and Furie2012). Therefore, we would expect deficit severity and deficit co-occurrence patterns to differ between acute versus chronic recovery stages, with more severe deficits typically seen during the acute stage.

It is apparent that right hemisphere stroke can lead to a variety of impairments. We do not, however, understand how often these various deficits co-occur or the relative likelihood of co-occurrence. This gap in the rehabilitation literature limits our ability to characterize RHD deficit profiles in a way that is clinically meaningful for diagnostic, therapeutic, and empirical purposes. The Right Hemisphere Damage Working Group (RHDWG) is part of the Evidence-Based Clinical Research Committee of the Academy of Neurologic Communication Disorders and Sciences. It was established to identify and distinguish core, co-occurring deficit patterns of cognitive-communication deficits following right hemisphere stroke reported in the literature by producing systematic reviews and meta-analyses to describe gaps in the extant literature and to form recommendations for future research. The ultimate goals are to develop (a) formal, evidence-based recommendations for the clinical diagnosis of “right hemisphere cognitive-communication disorder” (RH CCD) and (b) reporting guidlines for describing the clinical features that characterize research participants in studies of RH CCD. Multiple projects are being conducted simultaneously by the RHDWG, each focusing on a specific clinical question. Additional projects currently underway include a systematic review of neural correlates of aprosodia subtypes following right hemisphere stroke (Zezinka Durfee et al., Reference Zezinka Durfee, Sheppard, Blake and Hillis2021), a meta-analysis investigating aspects of emotional and linguistic prosody that are impaired in individuals with RHD (Stockbridge et al., In Press), and a systematic review comparing prosodic deficits associated with left versus right hemisphere stroke.

Existing descriptions of RHD sequlae are neither specified nor quantified in a way that is clinicially useful for standardized diagnostic purposes and the development of evidence-based guidelines for the co-occurrence of impairments. Aprosodia is important to the overall communication deficit profile after RHD due to its prevalence across the recovery trajectory as well as its impact on both interpersonal relationships (e.g., Hillis & Tippett, Reference Hillis and Tippett2014) and reintegration into previous societal and familial roles. The aim of this systematic review was to describe the presence and nature of relationships between specific forms of aprosodia (i.e., expressive and receptive emotional and lingustic prosodic deficits) and other cognitive-communication deficits and disorders (e.g., hemispatial neglect, pragmatics, executive functioning deficits) in individuals with RHD due to stroke. This particular focus was chosen because the existing, insufficient description of RHD results in inadequate and inefficient assessments as clinicians do not currently have evidence-based guidelines that can help them predict which RHD deficits are likely to co-occur. Because clinicians have limited time for assessment (Hawthorne & Fischer, Reference Hawthorne and Fischer2020), providing them with guidelines that help them predict which deficits are likely to co-occur or not co-occur together could help them maximize their time with their patients. Comprehensive, evidence-based assessment and treatment guidelines cannot be developed until the field has identified specific impairment profiles based on how these deficits cluster together and there is a better understanding of how individual deficits impact and influence each other. By consolidating findings across multiple studies, our goal was to make the first step toward better understanding of specific RH CCD impairment profiles and consequently, provide initial assessment recommendations.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted as part of a larger effort by the RHDWG. A portion of the search and review process was common to the larger project, with some methods specific to the current review. The complete methods for the larger project are described in Stockbridge et al. (In Press). An overview of methods specific to the current project are provided below.

Article Search

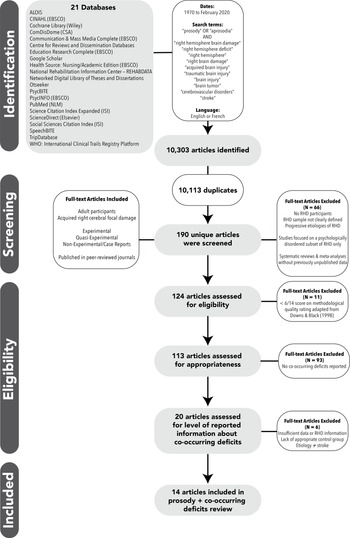

Briefly, 50 years worth (1970–2020) of research on prosody related to RHD was identified by searching 21 electronic databases. Inclusion criteria included adult participants (over age 18) with relatively focal lesions in the right hemisphere (cortical and/or subcortical) due to a variety of etiologies (stroke, tumor, surgical resection), for which data about participants with RHD could be separated out for analysis. Explicit diagnoses of aprosodia or other cognitive-communication disorders was not required. Prosody had to be a primary topic of interest in the study. Publication-type criteria included peer-reviewed publications (not abstracts) available in English or French with original data obtained through a variety of research designs (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, case studies). See Table 1 for the complete list of databases and search terms. Articles were excluded if they did not include a clearly identified RHD sample where specific RHD findings could be evaluated, included participants with progressive disorders that could potentially affect cognition, or only investigated individuals with psychological disorders.

Table 1. Search algorithms and findings

Article Screening and Quality Review

Multiple rounds of reviews were conducted to determine (a) appropriateness for the broad topic of prosody and RHD and (b) methodological quality. Members of the RHDWG reviewed the full articles to assess inclusion/exclusion criteria described above and to extract specific information from each included article. As described in Stockbridge et al. (In Press), 124 out of 190 unique articles passed the first two rounds of coarse selection filters. Next, using a rubric adapted from Downs and Black (Reference Downs and Black1998), seven reviewers independently evaluated the methodological quality of the 124 articles. For each paper, two of the seven reviewers rated the following: demographics, lesion variables, time post onset, definition of dependent variables, reliability of dependent variables, independent variables, methods, study design, localization methodology, lesion type, and handedness. Each article was given a total quality rating between 0 and 22 points (i.e., maximum score of 2 for each of the 11 rated variables), where a higher score indicated higher quality. Overall agreement within 2-points was 81%. Four articles had rating differences greater than 2-points. These articles were re-evaluated and resolved to within 2-points by the initial reviewers. Eleven papers were removed due to a low quality rating (i.e., total score of 7 or less; see Stockbridge et al., Under Review).

Following this review process, articles were examined for compatibility with the aim of the current systematic review: presence or characteristics of aprosodia and data from at least one measure of cognition or communication (Figure 1). Two members of the RHDWG independently reviewed each article to determine whether co-occurrence of aprosodia with any other cognitive-communication deficit was reported or if individual data were reported such that performance on prosody tasks could be compared to performance on other cognitive or communication tasks. Twenty articles met this criterion.

Fig. 1. PRISMA * Flow chart of article selection for systematic review.

The resulting 20 articles were then examined to determine whether there was enough information to make any judgments about co-occurrence of deficits. Due to the limited number of articles that either reported cognitive-communication disorders other than aprosodia or provided detailed participant demographics such that co-occurrence could be examined, there was no a priori list of cognitive or communication disorders used to determine inclusion. The following information was extracted from each of these 20 articles:

-

Total number of participants in the RHD group;

-

Etiology of RHD (only papers investigating individuals with RHD due to stroke were included);

-

Prosody variables (including how measured);

-

Co-occurring cognitive and communication variables (including how measured);

-

Description of co-occurrence (e.g., how many participants fit the pattern of co-occurrence (or lack of co-occurrence) described in the paper; statistics to support co-occurrence/correlation);

-

Depth of co-occurrence discussion (e.g., analyses vs. noted in discussion section).

Following this data extraction, six additional articles were excluded because they: provided insufficient data about co-occurring deficits (Bélanger et al., Reference Bélanger, Baum and Titone2009); lacked an appropriate control group to determine what neurotypical performance would be on a non-standardized prosody or cognitive-communicative task (Blonder et al., Reference Blonder, Heilman, Ketterson, Rosenbek, Raymer, Crosson and Rothi2005; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Orbelo, Cartwright, Hansel, Burgard, Testa and Buck2001); reported results for RHD group as part of a larger group, with no clear distinction of RHD participants’ data (Starkstein et al., Reference Starkstein, Fedoroff, Price, Leiguarda and Robinson1992, Reference Starkstein, Federoff, Price, Leiguarda and Robinson1994); or included only participants with an etiology other than stroke (Peper & Irle, Reference Peper and Irle1997).

RESULTS

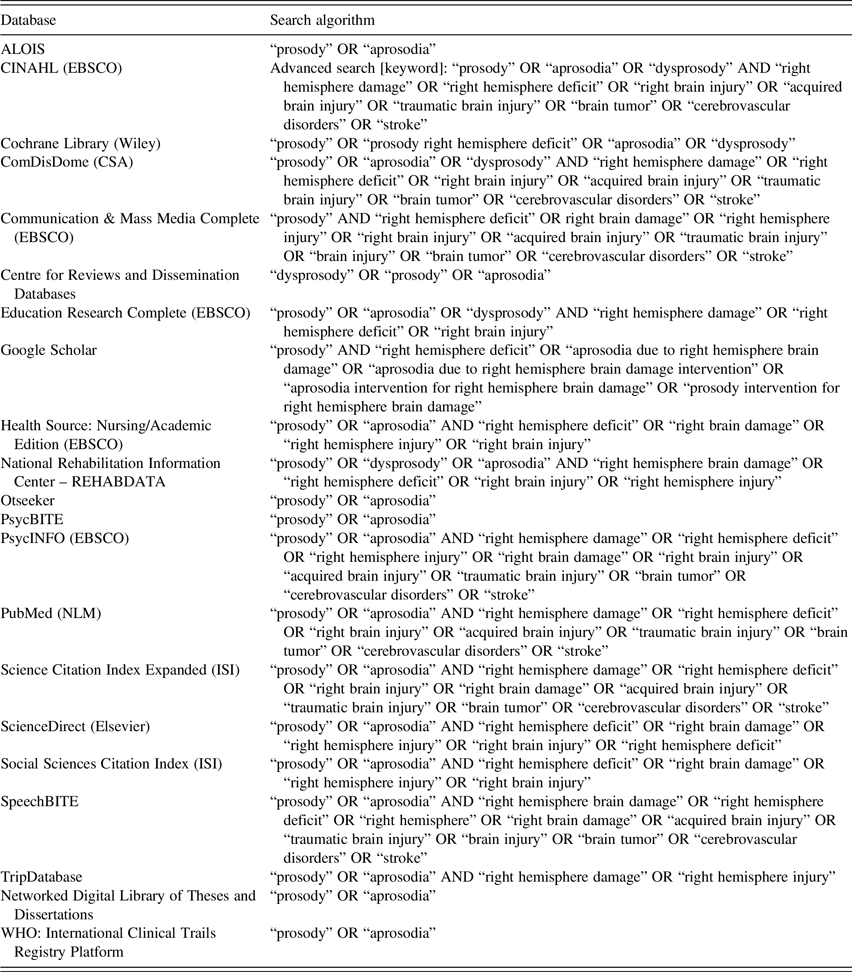

Of the 14 articles included, 12 investigated receptive emotional aprosodia and co-occurring deficits, and two articles investigated receptive linguistic aprosodia and co-occurring deficits (Figure 2; Table 2). The methods used to report and investigate co-occurring deficits in the reviewed papers included correlation analyses, between-group analyses (e.g., ANOVA), and cluster analyses. No studies were found that investigated the co-occurrence of expressive emotional or linguistic prosodic deficits with other cognitive-communication impairments. For interpretation of results, stages of recovery were defined as acute (within 1 week post onset), subacute (1 week to 3 months days post onset), and chronic (more than three months post onset).

Fig. 2. Aprosodia and co-occurring deficits in RHD systematic review results. The circle graph depicts deficits that have been studied along with receptive emotional and linguistic aprosodia in individuals with right hemisphere stroke. Individual studies contributing information to each deficit cluster are depicted within a categorical circle. Circle size indicates the RHD participant sample size both for individual studies, and the total RHD participant sample size for all studies in that category for categorical circles. For each individual study, if any evidence of co-occurrence was found, the study is depicted in dark green. The color of each categorical circle indicates an average of the strength of evidence of the individual studies contained within it. Specifically, the color of each categorical circle reflects the number of participants showing statistical evidence of co-occurrence out of the total number of participants in that category (the sum of all participants across all studies in the category).Footnote 1 Therefore, the color of each categorical circle (e.g., interpersonal interaction deficits, emotional facial recognition deficits etc.) indicates the amount of evidence of co-occurrence (darker = more evidence) taking into account evidence from all of the individual studies in that category.

Table 2. Summary of articles included in review of prosodic and co-occurring deficits in individuals with right hemisphere damage

Recovery Stage: Acute = <1 week post-stroke; Subacute = 1 week – 3 months post-stroke; Chronic = >3 months post-stroke.

RHD = Right Hemisphere Damage; SD = standard deviation; Subacute + Indicates participants in study were all at least at the subacute stage, but may have also included participants at chronic stage.

Aprosodia Battery (Ross & Monnot, Reference Ross and Monnot2008); ABaCo = Assessment Battery for Communication (Angeleri et al., Reference Angeleri, Bosco, Gabbatore, Bara and Sacco2012; Sacco et al. Reference Sacco, Angeleri, Bosco, Colle, Mate and Bara2008); FAB = Florida Affect Battery (Bowers et al., Reference Bowers, Blonder and Heilman1991); FAB-R = Florida Affect Battery Revised (Bowers et al., Reference Bowers, Blonder and Heilman1998); RHLB = Right Hemisphere Language Battery (Bryan, Reference Bryan1995).

Emotional Prosody Co-occurring Deficits

Emotional facial expression

Four studies investigated the co-occurrence of deficits in facial expression recognition and receptive emotional prosody (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Harciarek et al., Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006; Kucharska-Pietura et al., Reference Kucharska-Pietura, Phillips, Gernand and David2003; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002). Two of these studies found a significant positive correlation between deficits of facial expression recognition and receptive emotional aprosodia in the chronic stage of recovery (Harciarek et al., Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002). Harciarek et al. (Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006) assessed prosody using the Polish adaptation of the Emotional Prosody Task (Lojek, Reference Lojek2007) from the Right Hemisphere Language Battery (Bryan, Reference Bryan1995). Participants were asked to listen to nonsense sentences spoken with happy, sad, or angry prosody and to then choose the emotion that matched the sentence prosody. Harciarek et al. (Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006) reported a significant positive correlation (Spearman r = 0.52) between receptive emotional prosody and facial expression recognition tasks. Zgaljardic et al. (Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) assessed emotional prosody by asking participants to listen to semantically neutral sentences and choose the emotion conveyed in the sentence from eight possible choices (i.e., happy, pleasant surprise, interest, sad, fear, anger, disgust, unpleasant surprise). Zgaljardic et al. (Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) reported results at two chronic time points, with 1–2 years between each time point, and their correlation analyses revealed a significant positive correlation at time 1 (Pearson r = 0.69), but no significant correlation at time 2 (Pearson r = −0.11). Similarly, Kucharska-Pietura et al. (Reference Kucharska-Pietura, Phillips, Gernand and David2003) assessed receptive emotional prosody by having participants listen to semantically neutral sentences and then select the emotion (i.e., happy, sad, fear, anger, surprise, disgust, neutral) they thought was depicted in each sentence. All participants were in the subacute stage of recovery. Kucharska-Pietura et al. did not find a significant correlation between overall performances on this receptive emotional prosody task and a facial expression recognition task (Pearson r = 0.33). However, analyses of the seven individual emotions found significant correlations for fear (Pearson r = 0.48) and disgust (Pearson r = 0.38) across modalities (prosody and facial expressions). Only one of the four studies found no evidence of a relationship between facial expression recognition and receptive emotional prosody, which was investigated using two prosody subtests (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998). One subtest required participants to identify the emotion from among eight choices (i.e., happy, pleasant surprise, interest, sad, fear, anger, disgust, unpleasant surprise) in semantically neutral sentences. The second subtest was a discrimination task in which participants listened to two sentences spoken by the same speaker with either the same or a different emotion, and were asked to indicate whether the emotion was the same or different. In a group of participants spanning the subacute-chronic stages of recovery, no evidence was found of a significant correlation between facial expression recognition and performance on either receptive emotional prosody subtest (Pearson r range = −0.05 – 0.57, with no prosody subtest r reaching significance) (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998).

Emotional semantic knowledge deficits

Two studies examined relationships between receptive emotional prosody and emotional semantic knowledge deficits (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002). Both studies investigated semantic knowledge at the word- and sentence-levels at subacute and chronic recovery stages. Zgaljardic et al. (Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) asked participants to listen to semantically neutral sentences Footnote and choose the emotion that was used in the sentence from among eight possible choices (i.e., happy, pleasant surprise, interest, sad, fear, anger, disgust, unpleasant surprise). Zgaljardic et al. (Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) found a significant correlation (Pearson r = 0.69) between receptive emotional prosody and emotional semantic processing at the word-level in a group of participants who spanned the subacute and chronic stages of recovery (Time 1: 2–49 months post-stroke), but they found no significant relationship at the word- (Pearson r = 0.28) or sentence-level (Pearson r = .38) for participants in the chronic stage of recovery (Time 2: at least 14 months post-stroke). Borod et al. (Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998) did not find any significant relationship between two tests of receptive emotional prosody and emotional semantic processing (Pearson r range = .28–.38, none significant) in a group of participants spanning subacute-chronic recovery stages. As previously described, the first task asked participants to listen to semantically neutral sentences and identify the emotion from eight choices, and the second discrimination task required participants to listen to pairs of sentences and indicate if the emotion was the same or different.

Interpersonal interactions deficits

Four studies investigated the co-occurrence of receptive emotional aprosodia and deficits affecting different aspects of interpersonal interactions (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Heath & Blonder, Reference Heath and Blonder2005; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013; Parola et al., Reference Parola, Gabbatore, Bosco, Bara, Cossa, Gindri and Sacco2016). We defined interpersonal interactions as behavioral aspects of communication such as humor, pragmatics, or the expression of irony and empathy. First, Blake and colleagues (Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002) reviewed medical records of 123 individuals with right hemisphere stroke (ranging from acute to chronic stages of recovery) and identified 14 deficit categories. Cluster analyses were used to investigate which deficits had a tendency to co-occur. Results indicated that aprosodia clustered with two deficit categories: interpersonal interactions (i.e., eye contact, humor, pragmatics, overpersonalization) and hyperresponsive characteristics (i.e., verbosity and impulsivity). Heath and Blonder (Reference Heath and Blonder2005) focused on investigating spontaneous use of and response to humor among participants with subacute right hemisphere stroke. Emotional prosody was assessed using the Prosody subtest of the Florida Affect Battery – Revised (FAB-R; Bowers et al., Reference Bowers, Blonder and Heilman1998), which tests comprehension of both neutral and emotional prosody using a combination of identification and discrimination tasks. Spousal ratings of the change from pre- to post-stroke in participants’ humor production was significantly negatively correlated (Spearman r = −0.75) with the prosody score, indicating that less change in humor production was associated with a better receptive emotional prosody score. The authors concluded that patients with preserved ability to recognize emotion in speech are better able to communicate using humor post-stroke. The combined findings from Blake et al. (Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002) and Heath and Blonder (Reference Heath and Blonder2005) suggest that receptive emotional prosody may be tied to aspects of interpersonal interactions, including use of humor.

The findings from Leigh and colleagues (Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013) also suggest a relationship between receptive emotional prosody and interpersonal interactions. Specifically, they investigated both affective empathy and receptive emotional prosody in individuals with acute right hemisphere stroke (14 out of 27 participants had impaired affective empathy). Affective empathy refers to the ability to recognize and make accurate judgements about how another person feels and requires perspective-taking. Receptive emotional prosody was assessed using the prosody comprehension subtest of the Aprosodia battery (Ross & Monnot, Reference Ross and Monnot2008), which consists of listening to semantically neutral sentences, monosyllables (e.g., ba ba ba), and asyllabic tones (e.g., sustained “ah”), and identifying the emotion in which the stimuli were produced from four choices (i.e., happy, sad, anger, surprise). Leigh et al. (Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013) found that all participants with impaired affective empathy also had impaired receptive emotional prosody. However, 13 patients who had impaired receptive emotional prosody had intact affective empathy. Therefore, although there does appear to be a relationship between affective empathy and emotional prosody; patients with impaired receptive affective prosody will not invariably also experience difficulties with affective empathy.

Finally, Parola et al. (Reference Parola, Gabbatore, Bosco, Bara, Cossa, Gindri and Sacco2016) assessed receptive emotional prosody as well as irony production and comprehension. Receptive emotional prosody was assessed using the Basic Emotions task on the paralinguistic scale of the Assessment Battery for Communication (ABaCo; (Angeleri et al., Reference Angeleri, Bosco, Gabbatore, Bara and Sacco2012; Sacco et al., Reference Sacco, Angeleri, Bosco, Colle, Mate and Bara2008), during which participants must identify the emotion being used (i.e., happy, anger, fear, sad) in videos of an actor speaking pseudoword sentences. In a cluster analysis, there was no evidence of a relationship among RHD participants’ performances on a receptive emotional prosody task and irony comprehension and production tasks.

Hemispatial neglect

There were four studies of the co-occurrence of receptive emotional aprosodia and hemispatial neglect (Blonder & Ranseen, Reference Blonder and Ranseen1994; Dara et al., Reference Dara, Bang, Gottesman and Hillis2014; Tompkins, Reference Tompkins1991b, Reference Tompkins1991a). Three of the four studies investigated participants with RHD during the subacute and chronic phases of their recovery. Using the three prosodic perception FAB subtests (i.e., discriminate neutral prosody, discriminate emotional prosody, name emotional prosody) (Bowers et al., Reference Bowers, Blonder and Heilman1991), Blonder and Ranseen (Reference Blonder and Ranseen1994) evaluated whether there were significant differences in receptive emotional prosody abilities between groups with or without hemispatial neglect. No significant group differences were observed on a Mann–-Whitney U test, which suggested that receptive emotional prosodic deficits do not necessarily co-occur with hemispatial neglect. Tompkins (Reference Tompkins1991b) measured both reaction time and accuracy on a receptive emotional prosody task. Specifically, participants first listened to a short story (the prime) that semantically conveyed either a happy, angry, fearful or emotionally neutral mood. They were then asked to identify the mood from the set of four choices. Next, the receptive emotional prosody task required them to listen to a target sentence and select what emotion was conveyed prosodically in the semantically neutral sentence from the same set of four choices. Accuracy and reaction time data were compared on the target sentences. Prosody performance in RHD participants with and without hemispatial neglect were compared using two-way repeated measures ANOVAs: Consistent with the previous findings, there were no significant group differences identified. Using the same prosody task and a two-way ANCOVA analysis approach, Tompkins (Reference Tompkins1991a) investigated both automatic and effortful processing of receptive emotional prosody in the same RHD participants. The automatic condition discouraged participants from generating conscious expectations about the target phrase and the effortful condition encouraged participants to use association strategies. Once again, Tompkins and colleagues found no evidence of significant differences in prosodic processing between the RHD participants with versus without hemispatial neglect.

Dara et al. (Reference Dara, Bang, Gottesman and Hillis2014) assessed receptive emotional aprosodia and hemispatial neglect in a sample of patients with acute stroke-associated RHD to determine which deficit was most sensitive to right hemisphere stroke. Receptive emotional aprosodia was assessed using a word identification task and a monosyllabic identification task. For the word identification task, participants listened to semantically neutral sentences spoken with emotional prosody, and for the monosyllabic identification task participants listened to monosyllabic utterances (e.g., ba ba ba ba) that conveyed specific emotions through prosody. In both tasks, they listened to the stimuli and chose the emotion represented from among a set of six choices (i.e., happy, surprised, angry, sad, disinterested, or neutral). Dara and colleagues compared the percentage of RHD participants with receptive emotional aprosodia to the percentage of participants with hemispatial neglect. Results indicated that ∼80% of the RHD participants presented with receptive emotional aprosodia but only 18% presented with hemispatial neglect. While all of those with hemispatial neglect had aprosodia, the reverse was not true: many patients with severe aprosodia had no neglect. The authors concluded that hemispatial neglect and receptive emotional aprosodia are independent deficits.

Linguistic Prosody Co-occurring Deficits

Hemispatial neglect

Only one study investigated receptive linguistic prosody and its relationship to hemispatial neglect (Rinaldi & Pizzamiglio, Reference Rinaldi and Pizzamiglio2006). Participants were in the subacute – chronic stages of recovery from right hemisphere stroke and divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of hemispatial neglect. Linguistic prosody was assessed using a task in which participants judged emphatic stress in active (e.g., “The boy reads the book.”) and passive sentences (eg., “The book is read by the boy.”). Specifically, participants listened to pairs of linguistically identical sentences in which emphatic stress was placed on the same or a different word. Participants indicated whether the stress was placed on the same or a different word in each sentence pair. Difficulty discriminating emphatic stress in passive sentences was significantly negatively correlated (r = −0.57) with the presence of neglect. Also, participants achieved lower accuracy processing the initial part of active sentences, but this effect was reversed in passive sentences. The findings therefore suggested that leftward processing of deep sentence structure was related to hemispatial neglect. The authors postulated that hemispatial neglect specifically interacts with syntactically-structured acoustic input (i.e., sentences with agent of action, action, and recipient of action) and not just any form of spoken language input.

Amusia

One study investigated the co-occurrence of receptive linguistic prosody deficits and amusia, which is the inability to recognize or express musical tones (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Baum, Cuddy and Munhall2002). This was a case study of a man in the chronic phase of recovery following right hemisphere stroke who presented with both receptive and expressive amusia. Prior to his stroke he had 10 years of experience singing in choirs and a barbershop quartet and after his stroke he was only able to recognize familiar song melodies when the lyrics were also presented. In addition to amusia, he also had receptive linguistic prosody deficits as measured by a sentence intonation task and an empatic stress task. For the sentence intonation task, the participant and a group of non-brain-damaged controls were presented with pairs of sentences that were spoken as a statement and a question. Sentences were presented in three conditions: auditory only, visual only, and audio-visual). The participant’s performance fell more than three standard deviations below the mean of the controls on the auditory only and audio-visual conditions. The emphatic stress task required listening to pairs of declarative sentences in which the stress was placed on either the first or second noun, and indicating if the stress had been placed on the first or second noun (an “I don’t know” response was also allowed). This task also had auditory only, visual only, and auditory-visual conditions. Again, the man with amusia had poor accuracy on all conditions that fell more than three standard deviations below the mean of the controls.

DISCUSSION

We systematically reviewed the right hemisphere stroke literature to identify the presence and nature of relationships between four types of prosodic deficits (expressive and receptive emotional aprosodia; expressive and receptive linguistic aprosodia) and other disorders affecting cognitive-communication abilities. The review revealed significant gaps in the research literature regarding the co-occurrence of common right hemisphere disorders with prosodic deficits. Among 50 years of empirical publications, we identified only 14 articles with enough data to address the co-occurrence of any form of aprosodia with other common RHD cognitive-communication disorders.

The greatest number of studies investigated the relationship between receptive emotional aprosodia and emotional facial expression recognition (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Harciarek et al., Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006; Kucharska-Pietura et al., Reference Kucharska-Pietura, Phillips, Gernand and David2003; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002). The results indicate that there is likely a relationship between receptive emotional aprosodia and emotion recognition in faces. Two studies (Harciarek et al., Reference Harciarek, Heilman and Jodzio2006; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) found evidence of emotional facial expression recognition deficits among RHD participants in the chronic stage of recovery, while one study that included participants in the subacute recovery stage (Kucharska-Pietura et al., Reference Kucharska-Pietura, Phillips, Gernand and David2003) only found evidence of impaired recognition of fear and disgust, but not to emotions overall. In contrast, Borod et al. (Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998) included RHD participants ranging from the subacute to chronic stages of recovery and did not find any co-occurrence evidence. Given that two studies found evidence of co-occurrence of these two RHD issues in the chronic recovery stage, it is likely that some patients with chronic receptive emotional aprosodia will also experience long-term deficits recognizing emotions in faces.

Additionally, the evidence suggests that deficits affecting interpersonal interactions, including impairments of humor, pragmatics, and affective empathy, often co-occur with receptive emotional prosody deficits (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Heath & Blonder, Reference Heath and Blonder2005; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013; Parola et al., Reference Parola, Gabbatore, Bosco, Bara, Cossa, Gindri and Sacco2016). Evidence of co-occurrence of receptive emotional aprosodia and interpersonal interaction deficits were found in studies spanning acute to chronic recovery stages (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Duffy, Myers and Tompkins2002; Heath & Blonder, Reference Heath and Blonder2005; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013). This suggests that RHD patients with receptive emotional aprosodia are at risk for long-lasting interpersonal interaction deficits that may benefit from prosody treatment.

Receptive emotional prosody may be likely to co-occur with emotional facial expression recognition and interpersonal interaction deficits due to sharing common cognitive processes and brain regions. For example, Sheppard et al. (Reference Sheppard, Meier, Durfee, Walker, Shea and Hillis2021) proposed a three-stage model of receptive emotional prosody that includes interaction between stages of prosodic processing and domain-general emotion knowledge and processing. Specifically, they characterized three subtypes of receptive emotional aprosodia that resulted from impairments to different stages of the model. They found that some RHD participants with impaired receptive aprosodia had a domain-general emotion recognition impairment that spanned recognizing emotions in voices and faces. It is likely that impaired knowledge of emotions would also result in deficits of interpersonal skills and emotional facial recognition.

It is possible that impaired affective empathy could also result in deficits in recognizing emotions in voices and faces, as well as in interpersonal interactions. Affective empathy refers to the ability to recognize someone’s emotional state and respond with an appropriate emotion (Davis, Reference Davis1994). Affective empathy relies on both emotional contagion, which refers to being emotionally affected by someone else’s emotions, and perspective-taking, which is the abilty to ascertain how someone is feeling. Recall that Leigh et al. (Reference Leigh, Oishi, Hsu, Lindquist, Gottesman, Jarso and Hillis2013) found that all their RHD participants with impaired affective empathy also had impaired receptive emotional prosody; however, 13 of the 27 participants with impaired receptive emotional prosody had intact affective empathy. Their lesion analyses concluded that there is some overlap in the areas of the brain required for affective empathy and emotional prosody. Perhaps, as Sheppard et al. (Reference Sheppard, Meier, Durfee, Walker, Shea and Hillis2021) had conjectured, several subtypes of receptive emotional aprosodia exist, and one subtype of receptive emotional aprosodia can result from damage to brain areas that are also important for affective empathy, thus resulting in co-occurring deficits.

Several studies investigated the co-occurrence of receptive emotional aprosodia and hemispatial neglect. Overall, the results from four studies offered no evidence of co-occurrence of receptive aprosodia and hemispatial neglect at any stage of recovery following right hemisphere stroke (Blonder & Ranseen, Reference Blonder and Ranseen1994; Dara et al., Reference Dara, Bang, Gottesman and Hillis2014; Tompkins, Reference Tompkins1991b, Reference Tompkins1991a). Only two studies investigated receptive emotional prosody in relation to emotional semantic knowledge deficits (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002), and while there is some evidence of co-occurrence earlier in recovery from right hemisphere stroke, this relationship does not appear to be long lasting (Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002).

Similarly, two studies investigated the co-occurrence of receptive linguistic prosody deficits and deficits in other cognitive-communicative domains (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Baum, Cuddy and Munhall2002; Rinaldi & Pizzamiglio, Reference Rinaldi and Pizzamiglio2006). Keeping in mind that there were only two studies, one of which was a single case report, there appears to be, at best, emerging evidence of a possible relationship between receptive linguistic prosody and hemispatial neglect or amusia subsequent to RHD. Further this evidence for co-occurrence of receptive linguitic aprosdia and hemispatial neglect was found in participants ranging the subacute to chronic stages of recovery, which suggests that RHD patients with these deficits may experience chronic difficulties. In the case study, the man with receptive linguistic aprosodia and amusia was several years post-stroke, which similarly suggests some RHD patients may experience long-lasting co-occurring deficits of receptive linguistic aprosodia and amusia.

In terms of shared cognitive processes between linguistic aprosodia and hemispatial neglect that could account for impairments in both areas. Receptive linguistic prosody relies on the ability to process structured patterns of rate, rhythm, pitch, and duration, which is true of music as well (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Peretz, Tramo and Labreque1998). This possible shared processing is similar to that hypthesized by Rinaldi and Pizzamiglio (Reference Rinaldi and Pizzamiglio2006), that hemispatial neglect impairs the processing of syntactically structured auditory input through its effect on the deep syntactic structure of the sentence.

The current review highlights the significant gaps in the right hemisphere stroke research literature examining prosody. First, it is clear that the field has inadequately addressed the question of deficits co-occurring with aprosodia in RHD. While we know the different types of cognitive-communication deficits that can occur in individuals with RHD, research has not yet identified specific profiles of impairments based on how these deficits cluster together with different types of aprosodia. Second, no studies have investigated the co-occurrence of prosodic and executive functioning or memory deficits of any kind. We did identify studies investigating attention in the form of hemispatial neglect, but there were no studies investigating other areas of attention such as sustained or divided attention. Furthermore, while we did find two studies (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Cicero, Obler, Welkowitz, Erhan, Santschi and Whalen1998; Zgaljardic et al., Reference Zgaljardic, Borod and Sliwinski2002) investigating the co-occurrence of receptive emotional aprosodia and emotional semantic knowledge, we have no understanding of how different forms of aprosodia interact with other aspects of language processing. This type of research is essential both to inform how specific cognitive-linguistic deficits influence prosody but also for the development of prosody treatments that target or take into consideration possible underlying cognitive-linguistic deficits.

There is a lack of research examining the relationship between expressive aprosodia (emotional or linguistic) and co-occurring deficits. Research has identified some tentative relationships between receptive emotional prosody and a limited number of deficit domains (i.e., recognition of emotion facial expressions, hemispatial neglect, emotional semantic knowledge). However, we cannot say anything about patterns of co-occurring deficits involving expressive emotional or linguistic prosody, even though we know that some individuals with RHD will experience deficits with expressive prosody (Balan & Gandour, Reference Balan and Gandour1999; Baum & Pell, Reference Baum and Pell1997; Ferré et al., Reference Ferré, Fonseca, Ska and Joanette2012; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Oishi, Wright, Sutherland-Foggio, Saxena, Sheppard and Hillis2018; Ross, Reference Ross1981; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Saxena, Sheppard and Hillis2018).

It is essential to fill these research gaps for several reasons. First, this research is necessary to inform the development of appropriate assessment guidelines. For instance, if we discover that receptive emotional prosody deficits frequently co-occur with other deficits (e.g., hemispatial neglect, emotional facial recognition), then guidelines could be developed to help speech-language pathologists know when to assess areas of likely co-occurrence and identify patient profiles. Additionally, this research may provide supportive evidence for the development of evidence-based treatment programs. For example, if a clinician detects pragmatic issues in a patient, it may be the case that they are rooted in an underlying prosodic deficit. In that case, it may be most appropriate to target, at least initially, prosodic deficits in treatment. Of course, the opposite may also be true, that when a clinician detects prosodic issues, these issues could be rooted in a global pragmatic deficit. Future research is required to understand the nature of the relationship between prosodic and pragmatic deficits (Hawthorne & Fischer, Reference Hawthorne and Fischer2020).

The paucity of evidence regarding profiles of impairment associated with aprosodia in right hemisphere stroke is exacerbated by several factors that make it difficult to interpret findings and draw any strong conclusions. The studies reviewed were inconsistent in the demographic information provided about variables such as age, education, and time post-stroke. Moreover, studies often combined patients at early or subacute stages (within one or two months post-stroke) with those at late chronic stages (e.g., several years post-stroke), even though subacute and chronic recovery stages are likely to have quite different deficit patterns (Hillis & Tippett, Reference Hillis and Tippett2014). Many studies with small samples only reported group-level summary statistics; for example, only 7 of the 14 included studies provided any form of individual demographic information. With only group-level summary statistics, it is impossible to determine whether individuals showed disparate deficit patterns; studies that do provide individual data commonly reveal that varying proportions of right hemisphere stroke participants do not exhibit the deficit of interest. Failing to report individual demographic and task performance data in studies with small sample sizes is a missed opportunity that could have led to a richer dataset informing our understanding of individual impairment profiles. We also noted instances where correlations were reported without providing either their interpretation or sufficient information about subtest scoring conventions that would allow readers to conclude whether a negative correlation, for example, meant aprosodia was less likely or more likely to co-occur with that particular disorder. Additionally, studies often failed to statistically correct for multiple comparisons.

Based on the current review, we have several suggestions for future research that would help move the field forward. First, and at the most basic level, researchers should provide relevant demographic information and report individual data. As noted above, group data obscure the well-known heterogeneity of the RHD population and prevent a clear understanding of RH CCDs. Second, we suggest that researchers consider the ecological validity of the prosodic tasks. For example, it is particularly difficult to assess true expression and recognition of emotional prosody in a research laboratory because emotions have to be “manufactured.” Future research should address this concern whenever possible by considering the use of methods that increase ecological validity such as those that don’t draw the participants’ attention to prosody or those that use spontaneous speech samples (Diehl & Paul, Reference Diehl and Paul2009). Third, we recommend the development of standardized measures of receptive and expressive prosody as well as other associated disorders. We acknowledge that, historically, assessing expressive prosody using acoustic measures to quantify pitch and other aspects prosody has been cumbersome and costly in a clinical setting. However, newer technology allows for automatic methods of acoustic analysis using tablet-based applications, which are also becoming more affordable (Nevler et al., Reference Nevler, Ash, Jester, Irwin, Liberman and Grossman2017, Reference Nevler, Ash, Irwin, Liberman and Grossman2019). While tablet-based assessment currently lacks the sophistication required to evaluate all of the acoustic features that would be studied in a research laboratory, it offers an additional metric that could be used in conjunction with subjective clinical judgments.

Standardized assessment batteries would allow us to better compare studies of aprosodia and other common right hemisphere disorders. For example, in the aphasia literature it is common to report individual patient demographic information and results on standardized assessments such as the Western Aphasia Battery – Revised (Kertesz, Reference Kertesz2007) or the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass & Barresi, Reference Goodglass and Barresi2000), allowing clinicians and researchers to better understand individual patient profiles. New standardized assessments should also consider addressing how prosodic and other related RHD deficits affect body function or structure, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in accordance with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), 2001). That is, it is important to understand both the nature of aprosodia and other deficits associated with RHD, as well as their impact on individuals’ daily lives.

Finally, another avenue for future research is to determine whether the identified co-occurrences are due to shared cognitive-linguistic processes or simply shared neurological substrates. While this distinction is often difficult to make, double dissociations between two commonly co-occurring deficits in two or more individuals (e.g., statistically significantly better scores on one task in one individual and statistically significant better scores on the other task in another individual) provide evidence against a shared cognitive-linguistic process. This point further emphasizes the need for reporting individual participant data, which requires assessment of prosody and other RHD cognitive-linguistic impairments that have adequate psychometric properties and normative data.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review revealed significant gaps in the research literature regarding the co-occurrence of common right hemisphere disorders with prosodic deficits. Out of nearly 200 articles spanning 50 years of research, only 14 provided enough data collected via adequate methodological rigor to draw any conclusions about this issue. Those conclusions, therefore, are fairly tentative, but include important early takeaways: receptive emotional prosody is not statistically associated with hemispatial neglect but commonly, and sometimes significantly, co-occurs with deficits in emotional facial recognition, interpersonal interactions, or emotional semantics. Emerging evidence suggests receptive linguistic processing is associated with amusia and hemispatial neglect in some patients. Clearly, more rigorous empirical inquiry is needed to identify specific profiles based on clusters of deficits associated with RHD. Future research is vital to inform the development of evidence-based assessment and treatment recommendations for individuals with cognitive-communication deficits subsequent to RHD.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available from the authors by request. Please contact Dr. Shannon M. Sheppard at ssheppard@chapman.edu.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This research was partially funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (NIDCD) through P50 014664, R01 DC015466 and 3R01 DC015466-03S.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.