Introduction

Although phonetic mergers and splits have been fundamental to historical linguistics, dialectology, and sociolinguistics, there remain uncertainties regarding their social evaluations. It has been proposed that mergers and splits as part of the linguistic system lack social affect (Labov Reference Labov1994:343, Reference Labov2010:129). A growing body of research, however, suggests that there exist varying degrees of social awareness and/or social evaluations towards mergers and splits (Baranowski Reference Baranowski2013; Hall-Lew Reference Hall-Lew2013; Watson & Clark Reference Watson and Clark2013; inter alia). Nevertheless, most of the literature informing our understanding of mergers and splits has examined English vowels (M. Gordon Reference Gordon, Chambers and Schilling2013:204). Thus, to further examine the social meaning of mergers and splits, the current study analyzes the social evaluations of a consonant merger and its split in Andalusian Spanish in two speech communities.

Background

Mergers, splits, and social evaluation

The reversal of a merger has been disputed in the sociolinguistic literature under Garde's Principle, which states that ‘innovations can create mergers, but cannot reverse them’ (Garde Reference Garde1961:38–39; Labov Reference Labov1994:311), and Herzog's Principle, which states that ‘mergers expand at the expense of distinctions’ (Herzog Reference Herzog1965; Labov Reference Labov1994:313). Both principles have received immense support in diachronic and synchronic accounts of mergers. Labov acknowledges that an individual may be able to reverse a merger (Reference Labov1994:347–48), but it is unlikely for a split to occur at the level of ‘an entire speech community’ (Reference Labov2010:121). If a split were to occur it would be due to language-external reasons such as an educational campaign or media influence (Labov Reference Labov1994:345–48) or due to dialect contact (Hickey Reference Hickey, Kay, Hough and Wotherspoon2004:134; Thomas Reference Thomas2006:490). Recent studies, in fact, have demonstrated that with adequate dialect contact, a split is possible (Johnson Reference Johnson2010; Nycz Reference Nycz2013; Maguire, Clark, & Watson Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013; Yao & Chang Reference Yao and Chang2016; Regan Reference Regan2017b, Reference Regan2020). As a split runs contrary to language-internal tendencies, it provides an ideal context to examine the social meaning of a merger.

Labov (Reference Labov1994:343) states, ‘as a rule, mergers and splits have no social affect associated with them’ and ‘the evidence for the absence of social affect of splits and mergers is massive and overwhelming’. That is, non-linguists comment on words in which the merger is present, but not on the merger itself (Labov Reference Labov1994:343–44). For example, a New Yorker with the cot-caught distinction may be stigmatized by a West Coast listener for their ‘high back ingliding /oh/ in lost and coffee, but not for making the distinction between cot and caught’ (Labov Reference Labov1994:344). Thus, while speakers comment on ‘surface structure’ such as words or sounds within a word, ‘differences in the phonological inventory—mergers and splits’ are not subject to social attention nor ‘carry social affect’ (1994:344). In spite of the numerous studies on mergers, there has been little evidence of social awareness. For example, of Baranowski's (Reference Baranowski2007) 100 speakers in Charleston, none were aware of the cot-caught merger-in-progress. Although one speaker exhibited awareness of the fear-fair merger, one individual's awareness does not indicate a communal social evaluation of the merger (Labov Reference Labov2010:128–29).

Recent studies, however, provide additional evidence of social awareness and social affect of mergers/splits. Production studies have documented speakers’ awareness of mergers-in-progress such as ‘Mary's’ awareness of the cot-caught merger in San Francisco (Hall-Lew Reference Hall-Lew2013:374) as well as four speakers who commented on the pin-pen merger in Charleston (Baranowski Reference Baranowski2013:287). Based on these overt comments, Baranowski proposes that the pin-pen merger is an exception to Labov's claim as it is ‘above the level of awareness’ and ‘subject to negative social evaluation’ (2013:293). Similarly, perception studies have demonstrated implicit social evaluations of mergers/splits such as Watson & Clark's (Reference Watson and Clark2013) matched-guise study in Liverpool and St. Helen that found negative reactions to guises with the nurse-square merger. While not specifically investigating social evaluation, Hay, Warren, & Drager's (Reference Hay, Warren and Drager2006) study of the near-square diphthong merger-in-progress in New Zealand found that social categories impacted whether or not listeners heard the merger. Similarly, Koops, Gentry, & Pantos (Reference Koops, Gentry and Pantos2008) found that listeners in Houston were implicitly aware that older speakers were more likely to have the pin-pen merger.

Furthermore, it has been proposed that social meaning attached to a merger could promote a split. Specifically, Maguire et al. (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:234–35) claim that Herzog's Principle ‘may be compromised when the merger involved is, or becomes heavily stigmatized’. As an example, they state that the split of the nurse-north merger in Tyneside English occurred due to an influx of immigrants with the distinction in the 1900s, in which the presence of the two-phoneme system led to the stigmatization of the merger (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:235). Similarly, scholars have commented on the stigmatization of the ceceo merger in Andalusian Spanish as motivating its split into distinción (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995; Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Melguizo Moreno Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; Lasarte Cervantes Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Regan Reference Regan2017a, Reference Regan2020).

Regional dialect levelling

Large-scale societal changes throughout Europe have catalyzed dialect levelling of traditional dialectal features in favor of supra-local features (Auer & Hinskens Reference Auer and Hinskens1996; Hinskens, Auer, & Kerswill Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005; Britain Reference Britain, Llamas and Watt2009b). The changes from an agrarian, to industrial, to a post-industrial society resulted in increased dialect contact, mobility, education, and urbanization, contributing to dialect levelling (Hinskens et al. Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005:23–24). As Kerswill (Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003:223) notes, regional dialect levelling involves both processes of geographic diffusion as well as levelling or ‘the reduction of or attrition of marked variants’ (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986:98). Kerswill (Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003:231) suggests that local vocalic solutions are ‘the order of the day’, while consonants are subject to dialect levelling over larger regions.

While some posit that levelling occurs through short-term and then long-term accommodation (Giles & Powesland Reference Giles, Powesland, Coupland and Jaworski1997), others propose that speakers avoid certain highly localized features to appear more modern or cosmopolitan, while still pertaining to their larger region (Foulkes & Docherty Reference Foulkes, Docherty, Foulkes and Docherty1999:13–14; Watt Reference Watt2002:57–58; Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003:230). This has been documented in Andalucía, in which younger middle-class Andalusians with more formal education avoid certain traditionalFootnote 1 Andalusian phonetic and phonological features in favor of supra-local Castilian features. This is particularly the case in syllable-initial position (i.e. preference for distinción over ceceo or for affricate [tʃ] over fricative [ʃ] for /tʃ/), while still maintaining Andalusian features in syllable-coda position (i.e. aspiration or elision of coda /s/), forming a new intermediate variety of Andalusian Spanish (Hernández-Campoy & Villena Ponsoda Reference Hernández-Campoy and Villena Ponsoda2009:197–203; Moya Corral Reference Moya Corral2018:58; Villena Ponsoda & Vida Castro Reference Villena Ponsoda, Castro, Cerruti and Tsiplakou2020:149). Villena Ponsoda & Vida Castro (Reference Villena Ponsoda, Castro, Cerruti and Tsiplakou2020:149, 177) indicate that the identity of the speakers of this intermediate variety blends an ‘orientation towards modern life, urbanization’ and ‘faithfulness to southern traditional community values’.

Ceceo and distinción

Castilian and Andalusian Spanish differ in coronal fricative realizations due to distinct processes of merger of the four medieval Spanish sibilants (/ts/, /dz/, /s/, /z/). In Castilian Spanish, these sibilants were reduced into the voiceless interdental fricative /θ/ and the voiceless apico-alveolar fricative /s̺/ creating the norm known as distinción (Penny Reference Penny2002:124–25). Distinción reflects a direct grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence of /θ/ for <z,ci,ce> and /s/ for <s>, giving rise to minimal pairs such as casa-caza ‘house-hunt’. In Andalusian Spanish, the four medieval sibilants merged into dental /s̪/, phonetically realized either as ceceo or seseo (Penny Reference Penny2000:118–19, Reference Penny2002:124–25). Ceceo is realized as a voiceless dental fricative, represented as [s̪θ] (Penny Reference Penny2000:118), [θs] (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996), or [θ̪] (Hualde Reference Hualde2005:153) as it is perceptually similar to, but normally less fronted than [θ]. Seseo is realized as a voiceless (predorso-)alveolar fricative [s̪] (Penny Reference Penny2000:118; Hualde Reference Hualde2005:153). Andalusian speakers that produce distinción generally realize a (predorso-)alveolar [s̪] as opposed to a Castilian apico-alveolar [s̺] (Narbona Jiménez, Cano Aguilar, & Morillo-Velarde Reference Narbona Jiménez, Aguilar; and Morillo-Velarde1998:156). Although distinción has existed in northern Andalucía, it is not native to mid and southern Andalucía, but was brought into existence relatively recently through dialect contact and increased educational attainment (Narbona et al. Reference Narbona Jiménez, Aguilar; and Morillo-Velarde1998:155–60). In the mid twentieth century, traditional dialectology studies found that ceceo and seseo still predominated throughout Andalucía (Navarro Tomás, Espinosa, & Rodríguez-Castellano Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa; and Rodríguez-Castellano1933; Alvar, Llorente, Salvador, & Mondéjar Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973Footnote 2).

Sociolinguistic studies, however, in the cities of Granada (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995; Melguizo Moreno Reference Melguizo Moreno2007, Reference Melguizo Moreno2009; Moya Corral & Sosiński Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015), Málaga (Ávila Muñoz Reference Ávila Muñoz1994; Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Villena Ponsoda & Requena Santos Reference Villena Ponsoda and Santos1996; Lasarte Cervantes Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Molina-García Reference Molina-García2019), Jerez de la Frontera (García-Amaya Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008), Huelva (Regan Reference Regan2017a, Reference Regan2020), and Lepe (Regan Reference Regan2020) have demonstrated that ceceo is shifting to distinción. Similarly, studies in the cities of Sevilla (Santana Marrero Reference Santana Marrero2016, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017; Gylfadottir Reference Gylfadottir2018), Málaga (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Villena Ponsoda & Requena Santos Reference Villena Ponsoda and Santos1996), and Granada (Moya Corral & Sosiński Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015) have indicated that seseo is yielding to distinción. These studies have found that the split of ceceo (and seseo) into distinción is led by younger speakers, those with more formal education, and women.

Although the majority of previous studies have analyzed coronal fricative production, there have been a few social perceptionFootnote 3 studies. Harjus (Reference Harjus2017) conducted a perceptual variety linguistics analysis in Jerez and found that participants identified ceceo with their own locale, but did not associate ceceo with a lower social stratum. In Granada, Moya Corral & García Wiedemann (Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995) conducted a matched-guise experiment with four guises: distinción and [tʃ] (for <ch>); seseo and [tʃ]; seseo and [ʃ]; ceceo and [tʃ]. Listeners paired these recordings with four professions: distinción was most associated with the bank director, seseo and [tʃ] the bank teller, seseo and [ʃ] the taxi driver, and ceceo the doorman. Martínez & Moya Corral (Reference Martínez and Moya Corral2000) conducted another matched-guise experiment in Granada with three guises: distinción; seseo; seseo and [ʃ] (for <ch>). Distinción was evaluated as most prestigious, followed by seseo, and then seseo and [ʃ]. A potential confound in these studies is that coronal fricative evaluation was possibly influenced by the co-occurrence of /tʃ/ variation. Finally, while Santana Marrero's (Reference Santana Marrero2018:86) perception study in Sevilla analyzed global evaluations of Castilian and Andalusian Spanish, a few listeners explicitly commented, some positively and others negatively, on seseo.

Huelva and Lepe

Two nearby speech communities, the city of Huelva and the town of Lepe, were included in the study as it commonly is assumed that rural areas maintain traditional dialectal features and favorable attitudes toward these features. While there is a split of ceceo into distinción in both communities, this change is more advanced in Huelva due to earlier dialect contact (Regan Reference Regan2020). Thus, following Britain (Reference Britain and Al-Wer2009a), rather than focus on idealized notions of rurality or urbanity, this study aims to compare the attitudes of both communities focusing on social causes of change.

Both Huelva and Lepe have experienced significant changes since the 1950s when Alvar et al. (Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973) collected their data demonstrating a predominant ceceo norm in both communitiesFootnote 4. In Huelva, the largest catalyst for these changes was in 1964 when Huelva became home to one of Spain's largest industrial plants (Polo Industrial). Immigrants came from all over the province, especially from the north of the province (la sierra de Aracena) where distinción is the norm, and from other parts of Spain, for employment in the factories (Feria Toribio Reference Feria Toribio1994; Ruiz García Reference Ruiz García2001). This immigration brought distinción speakers into the city of Huelva (Morillo-Velarde Reference Morillo-Velarde, Jiménez and Ropero1997:209). Consequently, Huelva's population increased from 83,648 to 147,808 inhabitants between 1950 (INE 1950) and 2011 (INE 2011). Prior to the industrial plant, Huelva had an agrarian and fishing economy. The city then passed through industrialization, but has recently become increasingly service-oriented. Specifically, in 2011, 74.5% were employed in service, 6.5% in agriculture, and 19.1% in manufacturing/construction (INE 2011). The educational attainment of Huelva's population also changed considerably from 1950 (INE 1950) (37.9% no studies; 60.1% primary; 1.3% secondary/professional; 0.7% university) to 2011 (INE 2011) (9.9% no studies; 12.7% primary; 57.5% secondary/professional; 20.0% university).

While Lepe is only 33 km west of Huelva, it has remained economically independent due to its strong agricultural sector (Feria Toribio Reference Feria Toribio1994:190), resulting in an increase in population from 9,285 in 1950 (IECA 2016) to 26,538 in 2011 (INE 2011). Historically, Lepe has been a fishing and agricultural hub of the province, but has essentially lost its fishing industry. While Lepe maintains its agricultural sector, it is increasingly service-oriented. In 2011, 54.0% were employed in service, 29.7% in agriculture, and 16.3% in manufacturing/construction (INE 2011). The educational attainment of Lepe's population changed drastically from 1960Footnote 5 (INE 1960) (78.2% no studies; 21.0% primary; 0.7% secondary/professional; 0.1% university) to 2011 (INE 2011) (14.3% no studies; 20.7% primary; 61.8% secondary/professional; 3.2% university).

In order to explore the social meaning of a merger and its split, the current study was guided by three research questions: (i) What are the social evaluations of ceceo and distinción in Western Andalucía? (ii) How do these evaluations vary by listener and speaker characteristics? and (iii) What differences in social evaluations exist between Huelva and Lepe?

Methods

Stimuli

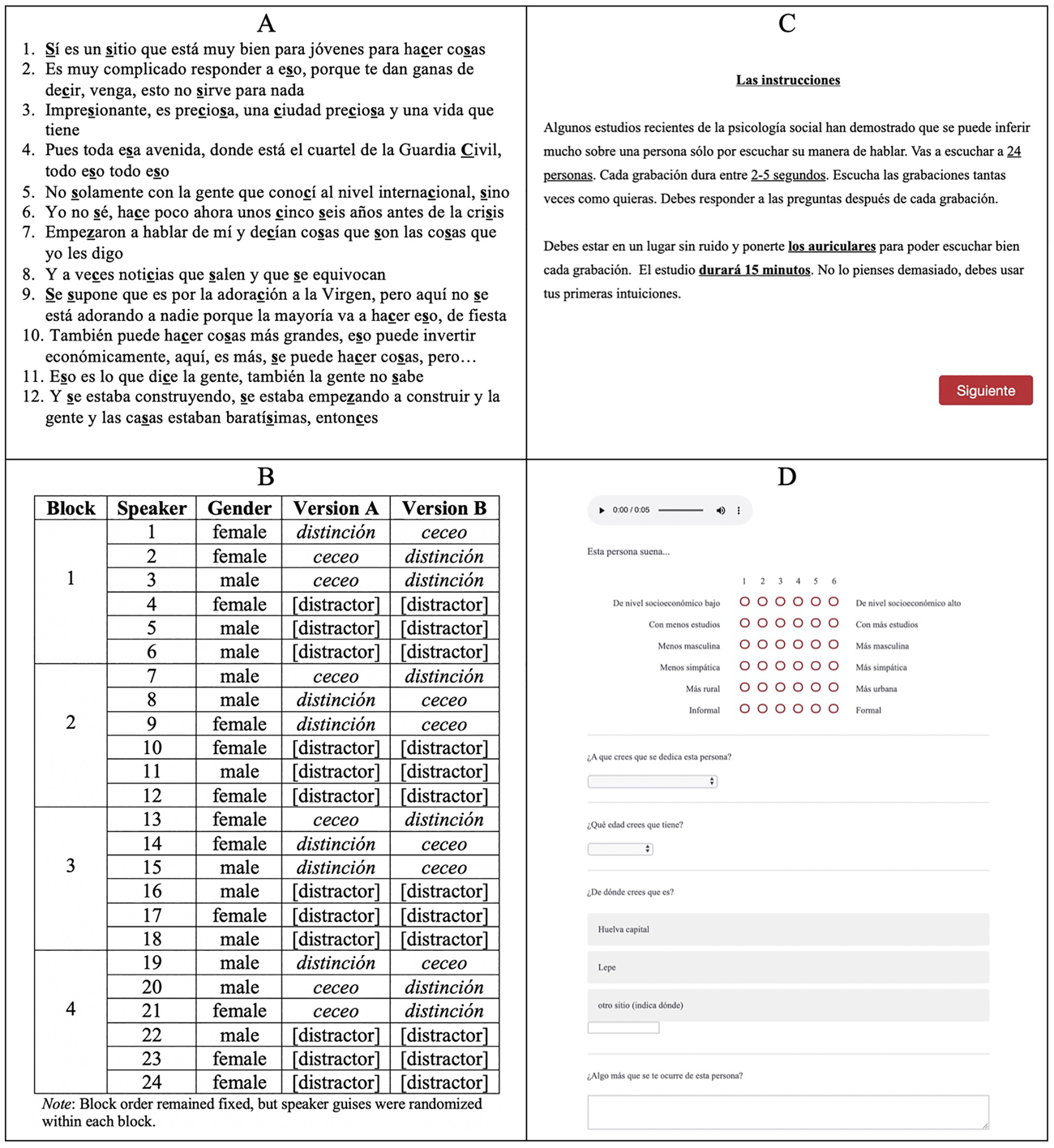

A matched-guise experiment (Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner, & Fillenbaum Reference Lambert, Hodgson; R, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960) was created to examine the social perception of ceceo and distinción. Following Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2007), the stimuli were taken from informal sociolinguistic interviews conducted by the author during 2015 and 2016. While spontaneous speech sacrifices some control over the content of the excerpts, it allows for a more natural sociolinguistic perception of speech (Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2007:34), as read and spontaneous speech differ substantially.

Participants were recorded with a Marantz PMD660 solid-state digital recorder wearing a Shure WH20XLR Headworn Dynamic Microphone with a sampling rate of 44.1kHz (16-bit digitization). Twelve speakers were included (age range: 23-53, M: 33.6, SD: 9.7), balanced by speech community and gender: six (three men, three women) from Huelva capital (age: M: 34.0, SD: 10.9) and six (three men, three women) from Lepe (age: M: 33.2, SD: 9.4). All speakers had obtained at least secondary education. The stimuli included a two to six second clip of spontaneous speech from each speaker (see box A in the appendix). To ensure that listeners would hear the coronal fricative realizations, recordings were selected based on the following criteria: (i) a minimum of two <s> tokens and one <z,ci,ce> token; (ii) never more <z,ci,ce> tokens than <s> tokens (an equal number was allowed); and (iii) a minimum of three and a maximum of six fricatives. While the number of fricatives varied per speaker (M: 4.7, SD: 1.2), it was balanced by gender (n = 28 fricatives per gender) and grapheme: all women together had seventeen <s> (M: 2.8, SD: 0.8) and eleven <z,ci,ce> tokens (M: 1.8, SD: 0.8), all men together had eighteen <s> (M: 3.0, SD: 0.9) and ten <z,ci,ce> tokens (M: 1.7, SD: 0.5). As ceceo has been shown to correlate with other Andalusian features (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996), the clips selected avoided the following: /tʃ/ (as it varies between [tʃ] and [ʃ]); word-internal coda /l/ (as it varies between [l] and [ɾ]); orthographic <ll> (as it varies between [ʝ] and [ʎ] in Lepe). Clips containing [s] for coda /s/, as opposed to [h] or [Ø], were excluded as this variety presents coda /s/ aspiration or elision (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda2008). Thus, co-occurring phonetic features with ceceo or distinción were avoided in the selection of clips to reduce confounds. Finally, phrases with reference to occupation, socioeconomic status, or specific place were excluded.

Guises were created by digitally manipulating the speech of speakers who produced both [s] and [θ] (or [s̪θ]). Most of these speakers produced distinción, while some varied between distinción and ceceo. Thus, each individual's fricatives were used to create one ceceo and one distinción guise per speaker (total of twenty-four guises) so that each individual's guises solely differed in fricative realizations. Only fricatives with a similar duration (ms) to the original fricative were spliced. When possible, the same phonetic context (previous and following vowels) for each spliced fricative was used. However, the same phonetic context was not essential as F2 onset frequency has not been shown to distinguish [s] and [θ] in Spanish or English (Jongman, Wayland, & Wong Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Martínez Celdrán & Fernández Planas Reference Martínez Celdrán and Fernández Planas2007). Following Styler (Reference Styler2017:31), the desired tokens were spliced at zero crossings using Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2018). Splicing was conducted by selecting a desired intervocalic coronal fricative from another segment of the same speaker's speech. All intervocalic [s] or [θ] were segmented following the guidelines of Jongman et al. (Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000:1255). The intensity (dB) of the newly selected fricative was adjusted to relatively match the fricative it would replace (taking into consideration that [s] should be several dB higher than [θ] and vice versa) prior to its insertion to avoid unnatural intensity differences. Once the new fricative was highlighted, both the start and end of selection were moved to the nearest zero crossing. At this point, the segment was copied. Before pasting it into the desired location, the cursor was moved to the nearest zero crossing at the start of the frication of the original fricative. The copied fricative was then inserted. Then the original coronal fricative was highlighted, the start and end of selection were moved to nearest zero crossing and the segment was deleted.

Once all guises were completed, each sound file was normalized for intensity in Praat (Modify > Scale Intensity) to bring all sound files to an overall range between 62–70 dB so that listeners would not have to change the volume. As intensity (dB) is a major acoustic cue for distinguishing [s] from [θ] (Behrens & Blumstein Reference Behrens and Blumstein1988; Jongman et al. Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Lasarte Cervantes Reference Lasarte Cervantes, Villena Ponsoda and Ávila Muñoz2012), clips were not adjusted more than 3 dB in order to preserve relative intensity differences between each fricative and following vowel. The resulting stimuli were checked by two native Andalusian speakers with training in phonetics. Both agreed that each guise sounded natural and they were easily able to identify ceceo versus distinción guises.

Experimental design

The guises were uploaded and organized into an online survey using Qualtrics (2005–2020). The two guises (ceceo, distinción) for each of the twelve speakers were divided into two separate surveys balanced by variant and speaker gender/origin (see box B in the appendix). Following Barnes (Reference Barnes2015), these two versions were branched so that each participant would be randomly assigned to one version. Consequently, listeners heard each voice only once. Splitting the experiment into two surveys reduced the time of completion and avoided voice recognition given each speaker's unique utterance.

There were twelve distractors from twelve additional speakers placed into each version, balanced by speaker gender/origin. The distractors did not include syllable-initial coronal fricatives. Each version of the survey was pseudo-randomized to ensure that listeners did not hear several ceceo or distinción guises back-to-back.

Upon consenting to the terms of the study, participants were told that they would hear two to five second recordings from twenty-four different speakers (see box C in the appendix). They were permitted to listen to each recording as many times as they chose and then had to respond to a series of questions. They were asked to wear headphones and listen to the recordings in a quiet place. After hearing each recording, the listeners had to rate each speaker on nine different questions (see box D in the appendix). The first six questions were a set of social characteristics based on a six-point Likert scale; an even number was implemented to avoid neutral responses following previous studies (Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2007; Walker, García, Cortés, & Campbell-Kibler Reference Walker, García, Cortés and Campbell-Kibler2014; Barnes Reference Barnes2015; Chappell Reference Chappell2016, Reference Chappell2018). For these social characteristics (only English scripts are provided here), they were asked ‘This persons sounds…’: (i) ‘of low socioeconomic level’/‘of high socioeconomic level’; (ii) ‘with less studies’/‘with more studies’; (iii) ‘less masculine’/‘more masculine’ for male voices and ‘more feminine’/‘less feminine’ for female voices; (iv) ‘less friendly’/‘more friendly’; (v) ‘more rural’/‘more urban’; and (vi) ‘informal’/‘formal’. There were also three multiple-choice questions. The first question of perceived occupation included: ‘works in a bar/restaurant’, ‘works in construction’, ‘works in a store’, ‘works in the field’, ‘is an administrator’, ‘is a teacher’, ‘is a doctor/lawyer’. The second question of perceived age included: < 30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, > 60. Finally, perceived origin included: Huelva capital, Lepe, and otro sitio ‘another place’. These questions were based on the author's participant observations and previous production findings in the region (Regan Reference Regan2017b, Reference Regan2020). Finally, after completing all twenty-four evaluations (twelve guises, twelve distractors), participants then answered basic demographic questions about themselves.

Implementation and participants

The survey was implemented online via a link. In winter/spring 2018 the link was sent to the author's social networks in Huelva and Lepe and posted on Huelva and Lepe Facebook pages. Additionally, El Diario de Huelva, a newspaper of the region, kindly promoted the study on their online edition. Upon clicking the link, potential participants were asked to consent to the terms of the study and confirm that they were both from Huelva or Lepe (or had at least lived half of their life there) and were at least eighteen years old. Those who consented and confirmed their eligibility continued while skip logic took ineligible participants to the end of the survey, preventing their participation. Responses to each question were obligatory in order to continue. Only completed surveys were considered for analysis.

242 listeners completed the study. However, twenty-one participants were excluded from analysis for confusing the direction of the scales (i.e. selecting doctor/lawyer as perceived occupation and then the lowest education level) or selecting the same number for each six-point scale for each speaker. Thus, there were 221 participants (seventy-eight men, 143 women) between eighteen and sixty-seven years of age (M: 37.1, SD: 10.4), stratified by education levels (eleven primary education, eighteen secondary education, twenty-four bachillerato, thirty-seven professional training, 102 university degree, twenty-nine graduate degree) that were included in the analysis. 126 participants were from Huelva capital (forty-eight men, seventy-eight women) and ninety-five from Lepe (thirty men, sixty-five women).

Statistical analysis

Following Barnes (Reference Barnes2015), perceived occupation was converted into a five-point scale based on occupational prestige scales in Spain (Carabaña Morales & Gómez Bueno Reference Carabaña Morales and Bueno1996) and perceived age was converted into a five-point scale. Given the discrepancy between five and six-point scales, all values were centered on zero. A principle component analysis using the princomp function was conducted in R (R Core Team 2019) with all eight continuous dependent measures to assess the potential number of underlying factors, followed by a factor analysis using the factanal function. The dependent measures of perceived friendliness, masculinity/femininity, and age received high uniqueness scores. They were analyzed independently and it was found that only masculinity/femininity demonstrated significant results in mixed effects linear regression models. Thus, perceived friendliness and perceived age were disregarded and a new primary component analysis and factor analysis were run with the remaining six dependent measures. Based on the Eigen values and a scree plot, it was determined that there were three underlying factors. The first factor was a combined ‘status’ factor, loading perceived socioeconomic level, education level, and occupational prestige. The second factor loaded perceived urban-ness and formality. However, there were several differences between measures that were missed when combining urban-ness and formality into a single factor, therefore resulting in these measures being analyzed separately. The third factor loaded only perceived masculinity/femininity, which was removed from further analysis as the best mixed effects model (i.e. lowest AIC) only included the main effect for speaker gender. Thus, there were a total of three continuous dependent measures: status, urban-ness, and formality.

For each of these dependent measures a separate mixed effects linear regression model was created using the lmer function (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2014) in R with two random intercepts of speaker and participant (listener) as well as the random slope of variant by participant. The independent variables tested in the various models included: variant (ceceo, distinción), speaker gender (male, female), listener gender (male, female), listener origin (Huelva capital, Lepe), listener education (1–5), listener age (eighteen to sixty-seven), and listener years lived away from Huelva/Lepe (zero to thirty). Listener years away serves as a limited proxy for geographic mobility. Listener education is a five-point scale based on educational levels: primary (1), secondary (2), bachillerato/professional formation (3), undergraduate degree (4), and graduate degree (5). All independent variables were tested in model construction with each social factor in interaction with variant. Three-way interactions between variant by listener origin by other social factors were tested to examine differences between communities. Within each model, non-statistically significant interactions with variant were removed from subsequent models. Estimated marginal means (Lenth, Singmann, Love, Buerkner, & Herve Reference Lenth, Singmann, Love, Buerkner and Herve2018) were used to conduct post-hoc analyses for interactions with more than two categorical levels.

As perceived origin was a three-way categorical dependent variable (Huelva, Lepe, otro sitio), a separate multinomial logistic regression model was fitted to the listeners’ evaluations of speaker origin using the multinom function in the nnet package (Venables & Ripley Reference Venables and Ripley2002). Z-scores and p-values were calculated manually.

Results

Each model demonstrates a significant main effect for variant (ceceo vs. distinción) and several significant interactions between variant and other independent variables. The results for each mixed effects linear regression model are presented in Table 1, displaying the estimate, standard error (SE), t-value, and p-value. Positive estimates indicate a higher evaluation, while negative estimates indicate a lower evaluation. Larger estimates in either direction from zero indicate a stronger effect of the main effect or interaction. Marginal R-squared (R2m) values and conditional R-squared (R2c) values are listed for each model to assess the goodness-of-fit of the variation per measure (Nakagawa & Schielzeth Reference Nakagawa and Schielzeth2013).

Table 1. Summary of mixed effects linear regression models for perceived status, perceived urban-ness, and perceived formality; speaker and listener as random intercepts and listener by variant as random slope; n = 2,652 for each regression. Reference levels are ceceo for variant, female for speaker gender, female for listener gender, and Huelva for listener origin.

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

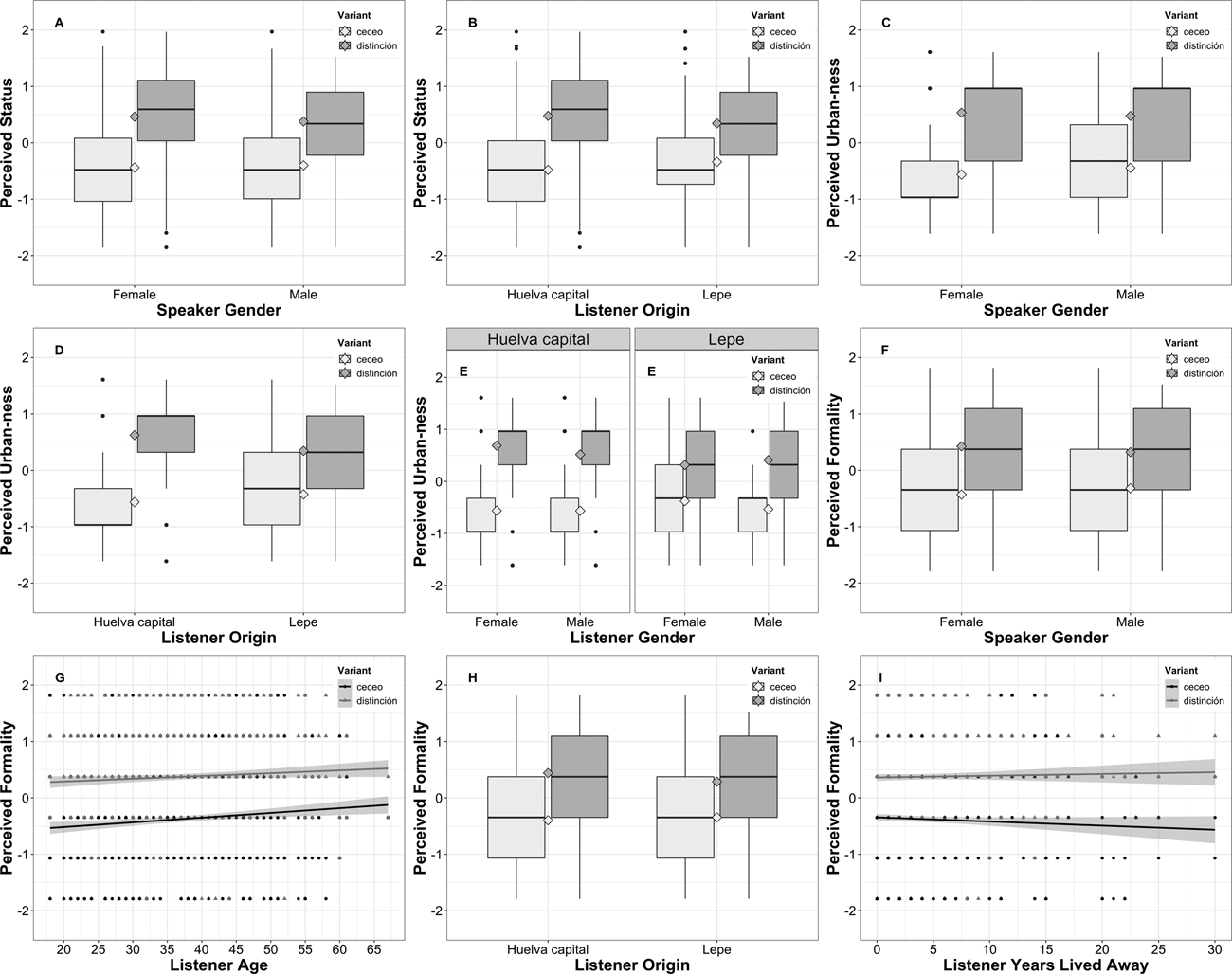

The perceived status model demonstrates a main effect of variant, in which speakers with distinción guises had higher perceived status than speakers with ceceo guises. The interaction between variant and speaker gender (Figure 1A) indicates that while both male and female speakers are perceived as having lower status with ceceo guises than with distinción guises, female speakers with ceceo guises are perceived as even lower status than male speakers with ceceo guises. The interaction between variant and listener origin (Figure 1B) indicates that Huelva listeners perceive distinción guises higher in status and simultaneously perceive ceceo guises lower in status than Lepe listeners.

Figure 1. Perceived status: variant by speaker gender (A), variant by listener origin (B); Perceived urban-ness: variant by speaker gender (C), variant by listener origin (D), variant by listener origin by listener gender (E); Perceived formality: variant by speaker gender (F), variant by listener age (G), variant by listener origin (H), variant by listener years lived away (I). Note: Positive numbers indicate a higher rating for each measure (i.e. higher status, more urban/less rural, more formal) while negative numbers indicate a lower rating (i.e. lower status, less urban/more rural, less formal). Figure 1 was created with ggplot2 (Wickham Reference Wickham2013).

The perceived urban-ness model demonstrates a main effect of variant indicating that speakers with distinción guises were perceived as more urban than speakers with ceceo guises. The interaction between variant and speaker gender (Figure 1C) indicates that while male and female distinción guises were perceived as equally urban, female ceceo guises were perceived as less urban (more rural) than male ceceo guises. The variant by listener origin interaction (Figure 1D) indicates that Huelva listeners perceived speakers with distinción guises as being more urban and simultaneously perceived speakers with ceceo guises as being less urban than Lepe listeners. Finally, a three-way interaction between variant, listener origin, and listener gender (Figure 1E) indicates that Huelva women perceived distinción guises as more urban and ceceo guises as less urban as compared to Lepe women.

The perceived formality model demonstrates a main effect of variant indicating that speakers with distinción guises were perceived as more formal than speakers with ceceo guises. The interaction between variant and speaker gender (Figure 1F) demonstrates that female speakers with distinción guises were perceived as more formal than male speakers with distinción guises while in turn, female speakers with ceceo guises were perceived as less formal than their male counterparts. The interaction of variant by listener age (Figure 1G) indicates that although younger speakers perceived all guises as less formal than older speakers, they evaluated ceceo guises as even more informal. The variant by listener origin interaction (Figure 1H) indicates that Huelva listeners perceived speakers with distinción guises as more formal and ceceo guises as less formal than Lepe listeners. The interaction of variant by listener years lived away (Figure 1I) indicates that listeners with more years lived away evaluated speakers with distinción guises as more formal and speakers with ceceo guises as less formal than those with fewer years away.

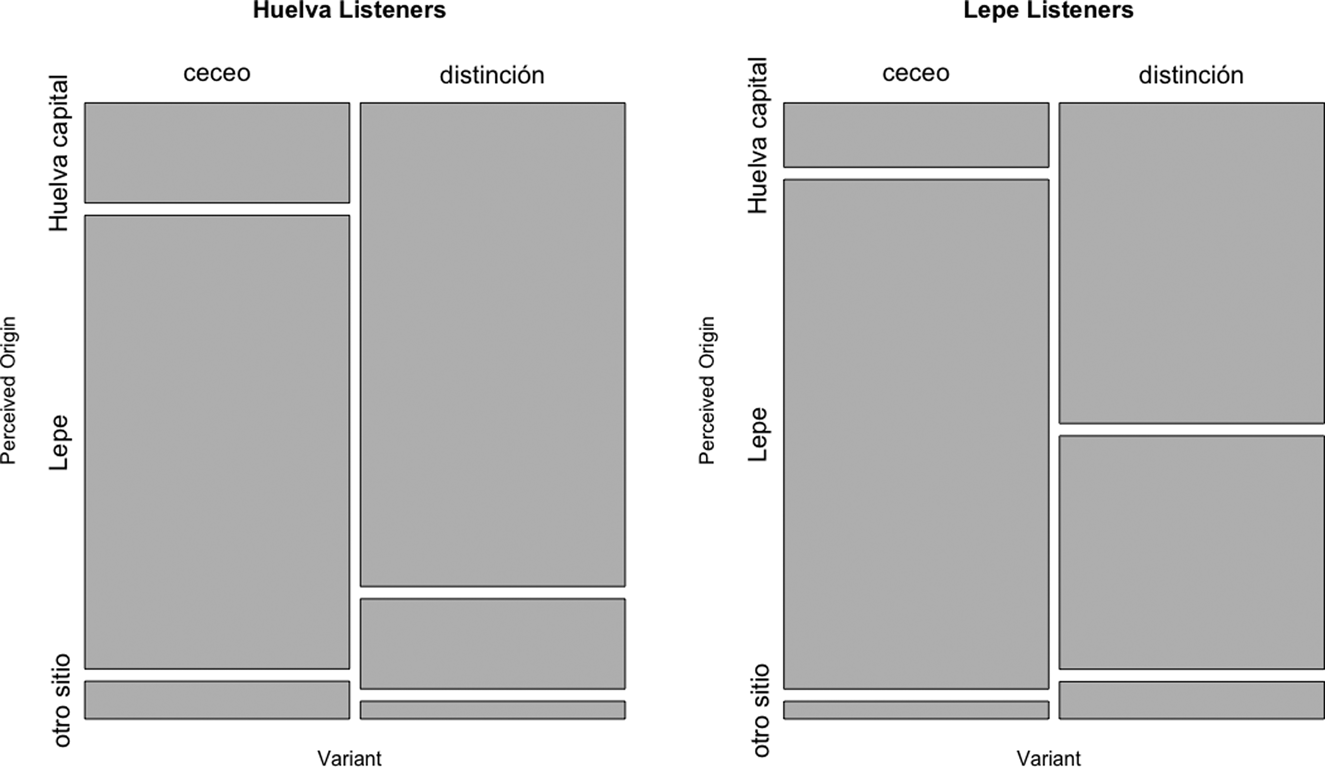

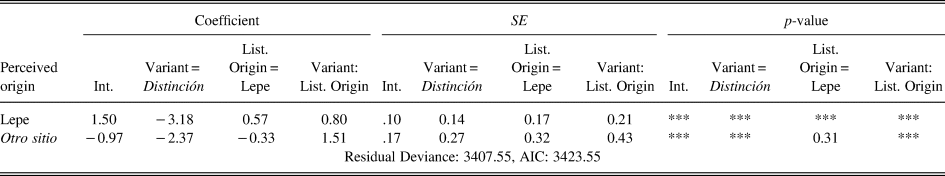

Table 2 displays the best-fit multinomial logistic regression for perceived originFootnote 6. The main effect of variant indicates that listeners were more likely to perceive speakers with ceceo guises as being from Lepe than from Huelva. The variant by listener origin interaction indicates that Lepe listeners were more likely than Huelva listeners to perceive speakers with ceceo guises as being from Lepe than from Huelva. However, Huelva listeners were more likely to perceived speakers with distinción guises as being from Huelva than Lepe listeners. That is, Lepe listeners demonstrated greater variation in perceiving speakers with distinción guises as being from Huelva and Lepe. Figure 2 presents a mosaic plot (a visualization of a contingency table) demonstrating that perceived origin varies by variant and listener origin.

Figure 2. Mosaic plot of variant by listener origin for perceived origin.

Table 2. Best-fit multinomial logistic regression model fitted to perceived origin based on variant and listener origin; n = 2,652. Reference levels are Huelva for perceived origin, Huelva for listener origin, and ceceo for variant.

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

In addition to Likert-scale and multiple-choice selections, there was an optional open-comment question for each guise (‘Anything else that occurs to you about this person?’). These comments are presented per guise type in Table 3.

Table 3. Listener comments on individual speakers per guise type (P = participant).

For ceceo guises, listeners demonstrated high metalinguistic awareness and even used the terminologyFootnote 7 ceceo. Many explicitly referenced graphemes such as <z> or the phoneme z, referring to /θ/: “this use of the z”, “a continual use of the phoneme z”, “the people of Lepe we pronounce the z”. The rest of the comments tend to fall into three larger categories: dialect recognition, negative intelligibility, and positive social affect. Many associated ceceo with Lepe such as: “clear Lepe ceceo”, “the ceceo of this person and the accent tell me that she is from Lepe”. Others acknowledged it could be of Huelva, but specifically “Torrejón” (one of Huelva's poorest neighborhoods) or “del barrio”. Other listeners remarked several negative social connotations towards intelligibility such as: “uncultured (fem.)”, “she is very crude speaking”, “I have had difficulties in understanding this person”. Some of the harsher comments (i.e. inculta, basta) are directed to female speakers. Finally, listeners also gave positive social affect comments such as: “easy-going (masc.)”, “he's an entrepreneurial man”, “I see a pleasant person”. Notably, these three comments were for male speakers. Taken together, these comments are similar to folk dialectology findings (Niedzielski & Preston Reference Niedzielski and Preston1999:366) in which linguistic forms lacking institutional prestige are valued higher in solidarity and lower in status.

For distinción guises, there was explicit reference to the presence of orthographic <s> and the phoneme /s/, many times indicating that it is not a local pronunciation such as “the S that she pronounces isn't characteristic of our area”, “by the way of pronouncing the S I wouldn't say that he's lepero”, “he sesea [verb] more than expected to be from Huelva”. However, one listener aptly commented that the speaker is “from the center of the city of Huelva”, a middle and upper-middle class neighborhood where distinción is most common in the city (Regan Reference Regan2017a). Other comments included positive status characteristics such as: “she appears more a TV or radio presenter”, “her profession could be a civil servant”, “she has a job working face-to-face with the public and adapts her speech so that it's less affected. She distinguishes s and c”. These comments inference pressures of the linguistic market (Sankoff & Laberge Reference Sankoff, Laberge and Sankoff1978). Furthermore, the last comment explicitly stated that the speaker distinguishes between <s> and <c>, referring to distinción.

At the completion of the study, participants were given the option to leave final comments. In example (1), a Huelvan gives his thoughts on linguistic variation throughout the province.

-

(1) 1 Hay muchos acentos o dejes dentro de la provincia de Huelva. Es característico el deje

2 de los pueblos costeros como Ayamonte, Isla Cristina y Lepe. En la sierra de Huelva

3 generalmente se pronuncia mejor y también se entiende más. En pueblos de la comarca

4 del Condado es donde peor se suele hablar o, mejor dicho, peor se pronuncia,

5 ya que su cercanía a Sevilla influye mucho. En Huelva capital se suele hablar

6 sin deje y con una pronunciación casi perfecta de las “c” y las “s” que también

7 se da en la sierra.

1 ‘There are many accents or intonations within the province of Huelva. It’s distinctive the accent

2 of the coastal towns like Ayamonte, Isla Cristina, and Lepe. In the mountain range of Huelva

3 generally one pronounces better and also one understands more. In towns of the

4 Condado region is where one tends to speak worse, or better said, one pronounces worse,

5 as its closeness to Sevilla influences it a lot. In the city of Huelva, one tends to speak

6 without accent and with an almost perfect pronunciation of the “c”’s and the “s”’s, which also

7 occurs in the mountain range of Huelva.’ (47-year-old male, Huelva)

He refers to the coastal towns as having distinctive accents, the areas most known for ceceo (lines 1 and 2), and claims that in la sierra (northern part of the province) is where one speaks better (lines 2 and 3). Conversely, la comarca del Condado is where people ‘speak/pronounce worse’ (lines 3 and 4). The listener states that Huelva capital speaks without an accent and has a near perfect pronunciation of ‘c’ and ‘s’ (as does la sierra), referencing graphemes and/or phonemes for producing distinción (lines 5 and 6). In this characterization of speech of different areas, one observes the semiotic processes of iconization and erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000).

In example (2), a Huelvan provides her thoughts on the presence of ceceo in Huelva.

-

(2) 1 Sólo informar que tanto yo, como mis padres y abuelos somos de Huelva capital y

2 que aunque hay gente en la capital que cecea, creo que es más por algún tipo de

3 acento heredado de sus padres o abuelos que pudieran ser de la provincia,

4 pero que el choquero sin influencias lingüísticas de otro lugar no suele cecear.

1 ‘Only to inform that I as well as my parents and grandparents are from the city of Huelva and

2 that although there are people in the city that cecea, I believe it’s more due to some type of

3 inherited accent from their parents or grandparents who could’ve been from the province,

4 but the choquero without linguistic influences of another place doesn’t tend to cecear.’ (41-year-old female, Huelva)

Although no one in her family speaks with ceceo, she recognizes that ceceo is present in the city, but believes it is due to an ‘inherited accent’ given by someone's parents or grandparents that are from the province (lines 2 and 3). While the construction of the Polo Industrial in 1964 brought workers with ceceo from nearby coastal towns, it also brought many workers with distinción from the north of the province and the rest of the Spain. Fractal recursivity and erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000) are observed in her characterization of fricative norms by separating those with family born in provincial towns from the choqueros (lines 3 and 4), the colloquial gentilic for Huelva capital (the official gentilic is onubense). While this insight overlooks previous accounts that ceceo was the norm in the city of Huelva (Navarro Tomás et al. Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa; and Rodríguez-Castellano1933; Alvar et al. Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973) before mass immigration due to the Polo Industrial, meaning that choqueros did and some still do produce ceceo, it also demonstrates an awareness that the current dominant norm in the city is distinción while ceceo is now more associated with nearby towns.

In example (3), a Huelvan provides his historical account for the current linguistic situation.

-

(3) 1 Hay que tener en cuenta que en Huelva se encuentra en una zona predominantemente ceceante

2 (la costa), pero que ha recibido mucha migración del resto de la provincia,

3 principalmente Andévalo y la sierra que son seseantes o diferenciantes.

1 ‘One must take into account that Huelva is located in a predominantly ceceante area

2 (the coast), but that it has received a lot of migration from the rest of the province,

3 principally the Andévalo and the mountain range of Huelva that are seseantes or differentiators.’ (24-year-old male, Huelva)

He situates Huelva in its larger dialect region, historically a ceceante area (Navarro Tomás et al. Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa; and Rodríguez-Castellano1933:233; Alvar et al. Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973) (lines 1 and 2). However, he notes the city of Huelva has received mass migration from the Andévalo (central part of the province) and la sierra. He explicitly labels them as seseantes (historical norm in the Andévalo) or differentiators, referring to distinción (historical norm in la sierra) (line 3). Thus, he infers that immigrants with distinción and even those with seseo changed the city's linguistic landscape through dialect contact, while the surrounding coastal area remains ceceante.

Other listeners addressed social connotations associated with ceceo. In example (4), a Lepera addresses the attitude that ceceo is associated with lower socioeconomic status.

-

(4) 1 Me gustaría añadir que el acento o ceceo no implica un nivel sociocultural bajo,

2 por desgracia, nuestro prejuicio nos lleva a pensar lo contrario.

1 ‘I would like to add that the accent or ceceo doesn't imply a low sociocultural level,

2 unfortunately, our prejudice leads us to think the contrary.’ (28-year-old female, Lepe)

Although she states that simply because someone speaks with ceceo ‘doesn't imply that they are from a low sociocultural level’, she acknowledges that stereotypes still lead many to make such judgments.

This association between ‘low sociocultural level’ and ceceo is addressed further by a Huelvan in example (5).

-

(5) 1 El tema del ceceo es controvertido. En principio puede sonar a nivel sociocultural bajo,

2 pero no tiene que ver. Muchas veces es simplemente la forma de hablar que

3 uno ha escuchado en casa, aunque a mí, personalmente no me gusta. Cuando no

4 se cecea en los ejemplos que he escuchado, me gusta llamarlo “andaluz estándar”.

1 ‘The theme of ceceo is controversial. In principle it can sound like low sociocultural level,

2 but it doesn’t have to do with it. Many times, it’s simply the form of speaking that

3 one has heard at home, although to me, personally I don’t like it. When one doesn’t

4 cecea in the examples that I have heard, I like to call it “standard Andalusian”.’ (35-year-old male, Huelva)

He recognizes the association of ceceo with a ‘low sociocultural level’ (line 1), but suggests that it is not necessarily a correct assumption (line 2). However, in line 3 he states that he does not like ceceo and prefers the examples without ceceo (i.e. those with distinción). Finally, he refers to the examples of speakers who produce distinción as ‘standard Andalusian’ (line 4), showing a preference for the new intermediate Andalusian variety (Moya Corral Reference Moya Corral2018; Villena Ponsoda & Vida Castro Reference Villena Ponsoda, Castro, Cerruti and Tsiplakou2020). Consequently, Table 3 and examples (1)–(5) demonstrate high metalinguistic awareness regarding ceceo and distinción: geographical and social distribution, diachronic changes, and social connotations.

Discussion and conclusion

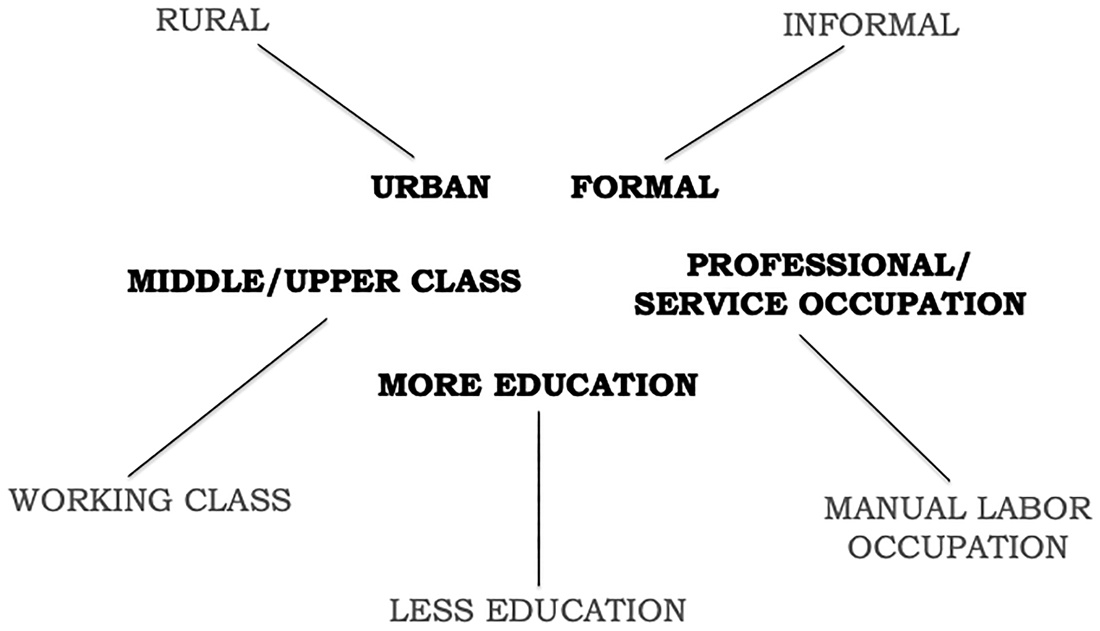

The main effect of variant for perceived status, urban-ness, and formality indicate that Huelva and Lepe listeners associated distinción with more overt prestige than ceceo, supporting previous matched-guise studies in Granada (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995; Martínez & Moya Corral Reference Martínez and Moya Corral2000). Specifically, speakers with distinción were perceived as being of higher status, more urban, and more formal than speakers with ceceo. These perception findings mirror the production studies throughout Andalucía in which speakers from higher socioeconomic levels, with more formal education, from urban areas, and of more professional occupations favor distinción (Ávila Muñoz Reference Ávila Muñoz1994; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995; Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Melguizo Moreno Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; Lasarte Cervantes Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Regan Reference Regan2020).

These perceptions, however, were influenced by listener and speaker characteristics. Regarding variant by speaker gender interactions, female ceceo guises were perceived as lower status, less urban (more rural), and less formal than male ceceo guises. However, female distinción guises were perceived as more urban and formal than male distinción guises. These findings provide insight into the motive of why women have led the split of ceceo into distinción throughout Andalucía (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann Reference Moya Corral and Wiedemann1995; Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Melguizo Moreno Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; García-Amaya Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Regan Reference Regan2020) as well as why ‘women adopt prestige forms at a higher rate than men’ in a ‘change from above’ (Labov Reference Labov1990:213, Reference Labov2001:274). Specifically, women adopt distinción as they are evaluated more negatively than their male counterparts when using the traditional Andalusian feature ceceo. This supports the notion that women use more institutionally prestigious supra-local features as a result of being evaluated more negatively than their male counterparts when using less overtly prestigious or highly localized features (E. Gordon Reference Gordon1997; Eckert & McConnell-Ginet Reference Eckert and McConnell-Ginet1999; Chappell Reference Chappell2016). This provides another example where women's linguistic behavior is ‘not a matter of self-promotion, but of avoidance’ of particular stigmatized features (E. Gordon Reference Gordon1997:47). That is, as Chappell (Reference Chappell2016:372) claims, women's adoption of a more prestigious variant may be ‘less of an option and more of a social necessity’. However, as gender interacts with other social factors (Eckert Reference Eckert1989; Labov Reference Labov1990) and that ‘within gender group’ differences may be more important (Eckert Reference Eckert1989:254; Eckert & McConnell-Ginet Reference Eckert and McConnell-Ginet1999:193), these findings should be explored further.

The variant by listener age interaction for perceived formality revealed that younger speakers evaluated ceceo as less formal than older speakers, indicating that younger listeners assign greater formality differences between the two norms than older listeners. These results reflect apparent-time production data (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; Regan Reference Regan2020) in which younger generations are more likely to produce distinción as well as perception data (Lasarte Cervantes Reference Lasarte Cervantes, Villena Ponsoda and Ávila Muñoz2012) in which younger speakers are more adept at discriminating between fricative realizations. The interaction between variant and listener years lived away demonstrates that listeners who have spent more years away evaluated distinción guises as more formal and ceceo guises as less formal than those with few to no years away. Thus, as Huelvans and Lepero/as become more mobile, presumably resulting in increased dialect contact, this affects their attitudes towards ceceo and distinción.

Listener origin by variant interactions indicated several differences between communities. Huelva listeners evaluated distinción guises as being of higher status, more urban, and more formal than Lepe listeners. Similarly, Huelva listeners evaluated ceceo guises as lower status, less urban (more rural), and less formal than Lepe listeners. The three-way interaction between variant, listener origin, and listener gender also indicated that Huelvan women evaluate distinción as more urban and ceceo as less urban than Lepe women. For perceived origin, Lepe listeners were more likely to perceive speakers with ceceo guises as being from Lepe, while Huelva listeners were more likely to perceive speakers with distinción guises as being from Huelva. These results complement recent production data (Regan Reference Regan2020) in which Huelva is more advanced in the split of ceceo into distinción than Lepe. Listeners appear to be aware of these differences. However, Huelva listeners, perhaps through processes of iconization, fractal recursivity, and erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000), assume that ceceo is from Lepe and distinción is from Huelva. Lepe listeners, on the other hand, demonstrate awareness that distinción is also present in their community. It is proposed that Huelva and Lepe may not differ in overall language attitudes, but rather in the rate of change in language attitudes, mirroring their rates of acquisition of the split of ceceo. While societal changes have occurred in both communities, their distinct historical and socioeconomic developments resulted in more educational attainment and earlier dialect contact in Huelva, which may explain the nuanced differences in language attitudes between communities. Thus, understanding ‘causal social processes’ in these communities is more insightful than focusing on rural-urban idealizations (Britain Reference Britain and Al-Wer2009a:224).

The quantitative evaluations and the qualitative comments indicate that ceceo has moved beyond a local dialectal feature and has acquired indexical values (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003). As Eckert (Reference Eckert2008:462) posits, previous studies (Labov Reference Labov1963; Zhang Reference Zhang2005; Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008) demonstrated that linguistic variables that previously distinguished geographic dialects ‘can take on interactional meanings based in local ideology’. It appears that ceceo is another case of a traditional dialectal feature passing through semiotic processes of ideology. While it originally only served as a dialect marker, it has acquired a constellation of social meanings within an indexical field (Eckert Reference Eckert2008) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Non-exhaustive preliminary indexical field of ceceo (gray) and distinción (black). Note: It is important to recognize that a ceceante speaker is not these labels (i.e. they are not less educated nor more rural than distinción speakers), but rather that these social characteristics reflect the implicit language attitudes of both communities.

Sociolinguistic theory of mergers and splits

As large-scale societal changes have promoted dialect levelling of traditional features throughout Europe (Auer & Hinskens Reference Auer and Hinskens1996; Hinskens et al. Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005), the current study demonstrates that they have also changed language attitudes towards certain traditional dialectal features. In Huelva and Lepe the changes in educational attainment, economies, and dialect contact have provided the adequate social context for ceceo to become stigmatized, which has served as a motivation for its split. Thus, the results support Maguire et al.'s (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:234–35) claim that sociolinguistic awareness and stigmatization may promote the split of a merger.

Given the social meaning attached to ceceo, it is not surprising that many Andalusians avoid this localized feature in favor of supra-local distinción, while still maintaining other Andalusian dialectal features in syllable-coda position, forming a new intermediate Andalusian variety (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena Ponsoda2008; Hernández-Campoy & Villena Ponsoda Reference Hernández-Campoy and Villena Ponsoda2009; Moya Corral Reference Moya Corral2018; Villena Ponsoda & Vida Castro Reference Villena Ponsoda, Castro, Cerruti and Tsiplakou2020). Furthermore, the national Spanish media routinely characterize the Andalusian variety as being unintelligible, vulgar speech, or inherently funny, among other insulting and unfounded stereotypes (León-Castro Reference León-Castro and Mancinas-Chávez2016:1589–93). Thus, given the stigmatization of a localized feature like ceceo, Andalusians wanting to avoid these stereotypes may opt for distinción. This lends support to the notion that speakers avoid certain highly localized dialectal features to appear more cosmopolitan, while still using other dialect features to maintain their regional identity (Foulkes & Docherty Reference Foulkes, Docherty, Foulkes and Docherty1999; Watt Reference Watt2002; Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003; Villena Ponsoda & Vida Castro Reference Villena Ponsoda, Castro, Cerruti and Tsiplakou2020).

The current study supports previous findings (Hay et al. Reference Hay, Warren and Drager2006; Koops et al. Reference Koops, Gentry and Pantos2008; Baranowski Reference Baranowski2013; Hall-Lew Reference Hall-Lew2013; Maguire et al. Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013; Watson & Clark Reference Watson and Clark2013) that speakers and listeners may have social awareness and evaluations of mergers and splits. However, the findings suggest a difference between the perception of a Spanish fricative merger and English vocalic mergers. As Kerswill (Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003) proposes, there may be differences between consonants and vowels in cases of levelling. The quantitative findings indicate that listeners have strong implicit social evaluations regarding ceceo and distinción, while the metalinguistic comments indicate that listeners possess a high degree of sociolinguistic awareness towards ceceo and distinción. That is, different from vocalic mergers in which only a few speakers or listeners comment on the sounds as part of specific words without direct reference to the structural property of the merger, these speakers in fact discuss the sounds themselves, including references to the phonemes and graphemes as well as utilize terminology regarding the merger and its split. Furthermore, listeners in examples (4) and (5) overtly connect social evaluations with the use of ceceo while listeners in examples (1)–(3) directly discuss the geographic variation of ceceo, seseo, and distinción in the province as well as the diachronic changes due to dialect contact from immigration.

These differences in social awarenessFootnote 8 and evaluations between a Spanish fricative merger and English vocalic mergers may be due to the sociolinguistic salience of ceceo. Here sociolinguistic salience is defined as ‘the level of awareness that speakers have of the variable, which in turn is connected to the social meanings that become attached to its variants’ (Llamas, Watt, & MacFarlane Reference Llamas, Watt and MacFarlane2016:2). Several scholars propose that highly salient features are prone to dialect levelling in situations of dialect contact (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986; Erker Reference Erker2017). Here salience is not due to extreme acoustic realizations (Podesva Reference Podesva2006), but rather due to frequency (Bardovi-Harlig Reference Bardovi-Harlig1987) and orthography (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986:11).

From both a usage-based framework (Bybee Reference Bybee2001) and an exemplar theory framework (Pierrehumbert Reference Pierrehumbert, Bybee and Hopper2001; Foulkes & Docherty Reference Foulkes and Docherty2006), syllable-initial coronal fricatives are highly frequent, which provides listeners with an infinite number of exemplars. For example, Regan's (Reference Regan2017b:292–98) analysis of spontaneous speech from twelve Lepe speakers for a selected four-minute clip of continuous speech from sociolinguistic interviews produced an average of 94.8 (SD: 25.4) syllable-initial fricatives per speaker. Thus, as listeners hear the speech of others, the social information of the speakers are accumulated and indexed to the stored exemplars (Foulkes & Docherty Reference Foulkes and Docherty2006; Hay et al. Reference Hay, Warren and Drager2006). This allows listeners to associate ceceo and distinción with certain social characteristics, particularly with dialect contact allowing for the existence of the merger and the split in the same speech communities. In contrast, the cot-caught or pin-pen vowels are less frequent in spontaneous speech and thus provide fewer exemplars for English speakers to associate social meaning. This is not to say that English vocalic mergers do not possess social meaning, but rather that there are degrees of salience (Barnes Reference Barnes2015) mediated by the number of exemplars each linguistic variable presents to the listener.

The role of orthography cannot be underestimated in the social awareness and evaluations of ceceo and distinción. As Labov (Reference Labov1994:345) notes, ‘the school system would logically be the major instrument for a social program to reverse mergers’, as seen in a few lexical splits (Wyld Reference Wyld1936; Abdel-Jawad Reference Abdel-Jawad1981; Lin Reference Lin2018). Different from vocalic mergers, prescriptive Peninsular Spanish presents a direct grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence for coronal fricatives. Given distinción is the official norm that is taught in the school systems throughout Andalucía, the current results reflect a type of ‘standard language culture’ (Milroy Reference Milroy2001:535) or ‘standard language ideology’ (Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green2012:67) that gives overt prestige to the prescriptive grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence. This could possibly be a main reason for differences between consonants and vowels (Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003), at least for mergers and splits. That is, there may be a more direct correspondence between graphemes and phonemes for consonants than for vowels (particularly for languages with a large vowel inventory like English). Thus, with a closer grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence, speakers are more able to produce splits and listeners more able to perceive sociophonetic differences between mergers and splits. As orthography and education go hand in hand, this is a principle mechanism of change in the production and perception of the ceceo merger and its split, particularly as Huelva and Lepe have seen notable increases in educational attainment.

Future studies should continue to examine the social perceptions of mergers and splits, particularly non-vocalic and non-English examples to increase our cross-linguistic understanding of the social awareness and evaluations of mergers and splits. The results of the current study have shed light into the ‘social motivation of a sound change’ (Labov Reference Labov1963). The implications are two-fold: (i) consonant mergers/splits may be subject to more overt social evaluation than vocalic mergers/splits due to frequency and orthography; and (ii) a merger can acquire social meaning, and this meaning in turn, may motivate its split.

Appendix: Experiment details

A: Stimuli phrases, B: Experimental design, C: Instructions, D: Screenshot of the survey questions per guise