Introduction

This research demonstrates how African immigrant women, through their interactions, enlist various discursive and linguistic practices to co-construct complex racialized and gendered identities. It focuses on ways these women discursively scale and take stances through deixis to make meanings about race that intersect with gender and their identities as immigrants. An intersectional lens to language studies is crucial because it helps us delve into ways various marginalities intersect to shape individual experiences and how they are reflected in larger structures (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). This inquiry provides a nuanced perspective into the lived experiences of African immigrant women, a racially marginalized group (for being Black women and immigrant women marginalized by the nation-state). This research helps us see how the African immigrant women co-construct differentiation based on their (lived/imagined) experiences to index multiple scalar stances and different ‘social types’ that span more than one spatiotemporal condition (Agha Reference Agha2005, Reference Agha2007).

Scholarship on immigrant identities has moved from looking at Black diasporic identities as connected due to similar ancestry. Black immigrants grapple with structures and histories not captured in language research. While past scholarship on Black immigrants has focused on their racial identities (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999, Reference Ibrahim2014; Copeland-Carson Reference Copeland-Carson2004; Arthur Reference Arthur2010; Smalls Reference Smalls, Koyama and Subramanian2014, Reference Smalls2015), this article investigates African immigrant women's identities beyond race. It examines the intersections of race with other marginalities, such as gender and transnationalism, through scalar and chronotopically organized interactions in the African diaspora. Often, when immigrants of African descent immigrate to any part of the world, they tend to be categorized homogeneously as either ‘Black’ or ‘African American’, which Ibrahim (Reference Ibrahim1999) refers to as a ‘social imaginary’. The social imaginary is where most Black individuals are imagined and constructed as ‘Black’, which is done without considering the individuals’ cultural, social, and historical experiences. I argue that by focusing on the lived experiences of African immigrant women and considering the particularities of Black womanhood (illuminated by ethnographic research, race, and gender theories), new and even more complex ways of understanding transnational identity formation emerge.

To illuminate the understanding of transnational identities of African immigrant women, this study presents a moment-by-moment analysis of culturally and socially situated conversations using historically grounded discourse analysis as outlined by Wortham & Reyes (Reference Wortham and Reyes2015). I examine the relationship between scale (Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016; Catedral Reference Catedral2018) and chronotope through deixis and shifters, and how participants employ them as they co-construct differentiation and distinction across different spatiotemporal frames. Data is from African immigrant women who relocated three to thirty years ago to the US. Most of the women I spoke to came to the US as international students (apart from a few green card holders). After their studies, they found jobs and settled in the US.

Using Du Bois’ (Reference Du Bois2007) conceptualization of stance, this article demonstrates how African immigrant women position themselves and others, evaluate others, and align with others. I employ the notion of scaling to demonstrate how interlocutors discursively connect their pre- and post-migration discourses to specific time spaces and particular social types (Agha Reference Agha2007; Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016; Catedral Reference Catedral2018). This research further theorizes scale as chronotopic (Lempert & Perrino Reference Lempert and Perrino2007; Blommaert & De Fina Reference Blommaert, De Fina, De Fina, Ikizoglu and Wegner2017; Catedral Reference Catedral2018; Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2021) because most of the activities and lived experiences of social actors do not occur randomly. When they occur, they usually allude to specific time and space and different ‘social types’ associated with those space/time configurations. The interactions of African immigrant women present different chronotopic frames that trigger distinct but extensive shifts in scaling lived experiences. They employ three discursive strategies: solidarity through difference and distinction, solidarity through denaturalizing difference, and solidarity through shared struggles and learning to construct racialized and gendered figures of personhood in the African diaspora.

This discussion also demonstrates how social actors employ different adverbial deixis terms (here-now and there-then) and referential deixis (such as we/us and they/them), and how these deictics invoke particular scales and chronotopes linked to specific space/times and different ‘social types’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010). First, I present a literature review on transnational and diasporic relations and the analytical and theoretical tools that are applied to analyze the excerpts. Then I explain the process of data collection and finally present the findings of the study.

Transnational and diasporic relations

Since the early 1990s, a significant amount of scholarship has focused on social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of transnational contexts. Due to changes in migration patterns, scholarship on migration no longer examines migrants’ identities as spatially bounded. Identities are examined as fluid, changing, and contingent on interactional contexts (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999, Reference Ibrahim2014, Reference Ibrahim2020; Smalls Reference Smalls2010, Reference Smalls, Koyama and Subramanian2014; Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018). Even though there has been some significant research focusing on race and gender in a transnational context, it does not consider unique aspects of these positionalities (race, gender, and transnationalism) among other marginalities in the African immigrant experience. Erel, Murji, & Zaki (Reference Erel, Murji and Nahaboo2016) note that as immigrants cross national and international borders, we must investigate how they situate their social practices and racial formations. This article aims to reconfigure the genericized construction of ‘the migrant’ figure of personhood (Agha Reference Agha2007) familiar in language and migration studies. This article considers the construction of ‘the migrant’ figure of personhood as a process or performative category that people perform live and experience in their daily interactions (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz, Hall, Watt and Llamas2011; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim2020).

Paving the way for ethnographic examinations of language, race, and identity among African immigrants, Ibrahim's (Reference Ibrahim1999) extensive research presents how Sudanese youth in Canada adopt US Black English to construct themselves as ‘Black’. Ibrahim's insightful work illuminates the inextricable links between language and race in the African diaspora. He looks at the process through which African English learners are racialized. He makes the students’ experiences the focal point of the study rather than teachers’ misconstructions and essentialization. This leads to the reproduction of hegemonic discourses about the racialization process. Ibrahim (Reference Ibrahim1999) demonstrates that African youths made efforts to identify with African Americans. They identified with the African American culture and languages through hip hop and used ‘Black Stylized English’ in their daily interactions.

Most importantly, these youths made linguistic choices based on their social conditions and experiences. They desired to belong to a group of other Black youths they came to value. For example, ‘to be Black in a racially conscious society, like the Euro-Canadian and U.S. societies, means that one is expected to be Black, act Black, and be marginalized’ (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999:353). These linguistic choices exemplify the salience of race (and gender to some extent) in African youth's lived experiences and signify a desire to belong to a particular kind of Blackness (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999, Reference Ibrahim2020). His work reveals that the ethnography of performance is a valuable tool for examining individuals’ experiences. It uncovers their identities and desires through verbal and non-verbal communication. The ethnography of performance has been utilized as a methodological positioning by Ibrahim, who states that as social beings, our identities are mirrored in our linguistic and cultural practices.

By contrast, Smalls’ (Reference Smalls2018) ethnographic work focuses primarily on the students’ discourses about race, difference, and belonging, rather than linguistic practices, to explore how they navigate the anti-Black discourses circulating around and among them and construct alternative meanings about Blackness (Smalls Reference Smalls2015, Reference Smalls, Alim, Reyes and Kroskrity2020). She investigates how they negotiate (cultural) differences and (political) belonging with other people racialized as Black to practice the ‘Black Diaspora’ (Smalls Reference Smalls, Koyama and Subramanian2014, Reference Smalls2015). The students’ statements about difference ‘actualized black heterogeneity and a diaspora that creates a common Blackness in which folks are invited or required to summon their cultural, gendered, class-based, religious-based, phenotypical, corporeal, and other differences’ (Smalls Reference Smalls2015:217). This research builds on Smalls’ and Ibrahim's groundbreaking work to illuminate better the complex nature of gendered and racialized identities of African immigrant women. This article mainly focuses on the intersection of race, gender, and transnational identities. Similar to Ibrahim's and Smalls’ elaborations on the integral role of difference in the diaspora, this study employs an intersectional perspective and African diaspora theory to theorize difference by examining different conceptions of race and how it intersects with gender and transnational identities in various space/time conditions.

In addition to filling gaps in the sociolinguistics literature on language, migration, and identity by focusing on the intersections of race, gender, and transnationalism, this work theoretically intervenes with regard to how these differences have been conceptualized and adopted. Generally, language and identity studies rely on typologies to predict specific discursive practices, indexical meanings, or acts of identity (Le Page & Tabouret-Keller Reference Le Page and Tabouret-Keller1985; Woodward Reference Woodward1997; Bauman Reference Bauman2000). For example, Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Duranti2004) influential ‘tactics of intersubjectivity’ (i.e. adequation and distinction, authentication and denaturalization, and authorization and illegitimation) provide invaluable analytical tools for examining the complexities of social identity in interactions. For instance, the tactic of adequation and distinction establishes similarities and differences between social groups and interactions. Specifically, people use the tactic of adequation to construct sameness, and the tactic of distinction to construct difference. When this tactic of distinction is examined, the differences that emerge from distinction tend to be understood as distancing and not as constructing belonging. Similarly, as Woodward (Reference Woodward1997) notes, identities are usually marked by pairing acts of identity (dis)alignment (we vs. they) and binary oppositions, such as Black vs. white and immigrants vs. natives. These oppositions are interpreted as distancing or insider versus outsider stances towards other groups. These generalizations and patterns of identity construction fail to capture interlocutors’ social and cultural aspects, making identity seem static and inflexible (Bauman Reference Bauman2000).

To capture the racial, gendered, and transnational aspects of the African immigrants’ identities, this investigation utilizes intersectional theory through the works of Collins (Reference Collins1990), Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1991), and Nash (Reference Nash2008, Reference Nash2018). Intersectionality is an analytical framework that calls into attention instructional and structural privilege and oppression based on gender, race, class, and age, among other marginalities such as transnational identities. Intersectionality, a theory that stems from Black feminist scholarship and activism, asserts that identity markers such as gender, race, sex, and class always intersect with other social structures of oppression and privilege and can vary depending on the context and experiences of marginalization (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991). This article suggests the use of intersectionality in examining how African immigrant women negotiate differentiation, as it is an excellent tool for examining issues regarding race and gender, among other marginalities in the discourses of marginalized individuals. As Nash (Reference Nash2008) states, intersectionality and intersectional projects bring to the forefront the experiences of subjects whose voices have been ignored or erased and organize the subjects’ experiences across and beyond borders. There is a need to understand that oppression and discrimination intersect with various axes of identity, including migrant identities. Oppression and discrimination based on race, gender, and transnationalism are experienced together, not independently of each other. Lorde (Reference Lorde1984) explained that when we do not consider how different communities construct differences, these differences are misnamed or erased. Lorde's theory of difference encourages researchers to explore and acknowledge the differences (regarding race, age, gender, and class) within different communities. This article adopts Mohanty's (Reference Mohanty2003) conceptualizations of ‘feminist solidarity’ as a basis for accounting and acknowledging differences, most importantly, sensitive to the context and considering spatiotemporal and historical frames. She describes the practice of feminist solidarity as follows:

Rather than assuming an enforced commonality of oppression, solidarity foregrounds communities of people who have chosen to work and fight together. Diversity and difference are central values here—to be acknowledged and respected, not erased in building alliances. Solidarity is always an achievement resulting from an active struggle to construct the universal based on particulars/differences. The praxis-oriented, active political struggle is important to my thinking. I believe that feminist solidarity constitutes the most principled way to cross borders—decolonizing knowledge and practicing anticapitalism critique. (Mohanty Reference Mohanty2003:7)

Examining how diasporic subjects construct solidarity and difference brings various standpoints from different social locations and times. It leaves room for new ways of understanding difference, which disrupts the dominant conceptions of solidarity and differentiation.

Scaling and stance-taking through deixis

This article combines scale, scaling, and chronotopes to demonstrate how they foster connections and distinctions among African immigrant women in the diaspora. As participants move from one discursive space to another, identities are sometimes scaled up or down depending on the context, setting, and interlocutors; scales help interlocutors make distinctions and relations that can be measured (Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016; Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). This article adopts the notion of scale and scaling (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007, Reference Blommaert2010; Koven Reference Koven2013, Reference Koven and Piazza2019; Carr & Lempert Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016; Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016; Catedral Reference Catedral2018) and Bakhtin's notion of chronotope (Agha Reference Agha2007; Blommaert & De Fina Reference Blommaert, De Fina, De Fina, Ikizoglu and Wegner2017; Catedral Reference Catedral2018; Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2021) to illuminate the complex characteristics of the context. Bakhtin (1981) characterized chronotope as a link between space and time in social events. This concept was primarily used as a literary analytic but it is crucial in theorizing meaning making. Agha (Reference Agha2007) expounds the notion of the interconnectedness between space and time to include personhood. As scholars, we need not examine chronotopes as real things in the world but as ideologies that are circulated and used differently. Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2015) describes chronotopes as ‘invokable chunks of history’ while scales as ‘scopes of communicability’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015:111–12). As social actors interact in different spaces and times, they convey specific information or depict a particular image. However, it is only possible if the chronotopes are inducted within the appropriate scales/levels. Rather than African immigrant women functioning either in the continent or the diaspora, they go back and forth in local and diasporic time/space dimensions as they narrate some ‘small scale’ and ‘large scale’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015) chronotopes. Scales are interconnected chronotopes (Goebel & Manns Reference Goebel and Manns2020). A scalar analysis presents a chance to investigate the social interactions of African immigrants as being negotiated on different scales and within diverse chronotopic frames. In this article, I characterized chronotopes as lower scale and higher scale (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007; Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2021). Categorizing scales as lower scale exhibits the social actors’ past and present lived experiences, and higher scale exhibits the racialized and stereotypical images of Black individuals in the diaspora. Their past and present chronotopic experiences depict the more cultural, ethnic, and personal experiences (lower scale) in Kenya and the US. In juxtaposition, the racialized experiences depict the immigrants’ understandings of race and gender and how it operates in institutions and power structures in the US (higher scale). Through these complex processes, the women co-construct similarities and differences. Even though they flesh out their differences in various chronotopic frames and scalar levels, they do so to construct solidarity rather than distinction. These dimensions do not require a preset scale; instead, they enable connections and distinctions between agency, subjects, and spatiotemporal orientations through narrated and narrating events (Jakobson Reference Jakobson1957/1971; Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016).

I conceptualize scaling as how African immigrant women construct differences linked to specific time-space configurations and personhoods (Carr & Lempert Reference Carr, Lempert, Summerson Carr and Lempert2016; Gal Reference Gal, Carr and Lempert2016; Catedral Reference Catedral2018). This is because scaling practices are not only situated interactionally or locally, they are informed by different institutional, historical, social, and cultural practices (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). As African immigrants interact, their interactions are situated within specific time-space configurations (home countries and the US diaspora); thus, a change in time or space in the narrating or narrated event often prompts a change in participant positionality, and settings (Blommaert & De Fina Reference Blommaert, De Fina, De Fina, Ikizoglu and Wegner2017). This study demonstrates that African immigrant women negotiate differences by orienting to different spatiotemporal frames and smaller and larger scales as they position themselves as part of ‘multiple scales of collective experience’ (Pritzker & Perrino Reference Pritzker and Perrino2021:2).

Participants’ scaling practices always invoke particular stances during an interaction. The scaling practices involve the social actor's viewpoint, which always points to (indexes) different aspects of the context, and these connections are facilitated by deixis. The shift in viewpoints is an act of stance-taking. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois2007:163) defines stance as a ‘public act by a social actor, achieved through overt means of communicative means, of simultaneously evaluating objects, positioning subjects (self and others) and aligning with other subjects’. For instance, a subject can perform a scale jump from a local scale to a translocal scale or from an individual scale to a collective scale; a change in stance facilitates this scale jump and is also indexical.

Furthermore, when a social actor shifts from one scale to another, this shift indexes socially and culturally constructed identities. When subjects perform a ‘scale jump’ or adopt different stances, they often employ ‘shifters’ such as personal pronouns (I, my, our, we, us, they, them), aspects of time (temporal; now, then, today, or tomorrow), or space (here, there) to connect their pre- and post-migration experiences. When an interlocutor changes their references or space-time configurations, it can be referred to as a change in stance or an invocation of a chronotope. Deixis is defined by Levinson (Reference Levinson, Asher and Simpson1983) as the relation between language and context, also known as ‘shifters’ (Reference JakobsonJakobson 1957/1971; Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Basso and Selby1976). My analytical toolkit (scales, scaling, indexicality, and stance) allows me to see how the social actors construct and negotiate their raced and gender intersubjective identities, using scaling and stance-taking through deixis.

Methods

The discourse segments analyzed in this study are from a more extensive ethnographic project investigating language, gender, race, transnationalism, and the construction of Blackness among African immigrants in the US. Data collection for this project involved participant observation at various community events (such as African student organization (ASO) events, birthdays, baby showers, Easter celebrations, Independence Day celebrations, community outreach events, church services, naming ceremonies, graduation ceremonies, and women's biweekly bible study fellowships, among others) and in participant households. Data collection for this project yielded thirty hours of audio recordings of casual conversations between African immigrant women and me. The data presented in this article came from three naturally occurring audio-recorded conversations with African immigrant women. The participants were four African immigrant women—who I call Shiko (age sixty at the time of recording), Achieng (fifty-four), Sarah (fifty), and Nafisa (fifty-seven)—and Achieng's spouse, Juma (fifty-three), the only man present in these conversations. They immigrated to the US to further their studies but settled after their studies and built their careers and families after completing their studies. Shiko, Achieng, Sarah, and Nafisa had lived in the US for thirty-four, thirty, twenty-six, and fifteen years, respectively.

I am a thirty-two-year-old cisgender woman, a wife, and a mother of two sons. I was born and raised in Kenya and came to the US as an adult in 2013. I came to the US as a Fulbright scholar and later began my graduate studies in the Midwest. I was welcomed to the community by this group of women. Reflexivity is crucial in my work, as it enables me to examine how my gender, sexuality, social class, and race influence my identity (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim2014; Lichterman Reference Lichterman2017). As a Black African immigrant woman in the diaspora, my identity has contributed to framing the questions asked and issues discussed throughout this article. I am also guided by my cultural knowledge and lived experience as a Black woman in the diaspora with connections to an African country, Kenya. Our diasporic experiences spurred my desire to research how gender and race are co-constructed with transnationalism among African immigrant women. When collecting data, I found that the voices and experiences of African immigrant women resonated with my own. Even though I am considered a community member by the participants, it is possible that they modified their behavior when they were aware that they were being recorded. Ethnographic methods are beneficial because they have allowed me to continue to share informal findings with my community when we meet, and I receive feedback from my participants. Therefore, I shared my informal analyses with the participants throughout the study.

Before I conducted my analysis, I listened to recordings several times and transcribed the segments that answered my research questions using Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson's (Reference Sacks, Schegloff, Jefferson and Schenkein1978) transcription conventions for conversation analysis (see the appendix). In the data, I coded for personal pronouns (we/us/our, they/them/theirs), spatial deixis (here, there), and temporal deixis (now, then). I also coded for the different stances that subjects took and the positionalities it helped them take. After coding, I linked participants’ conversations across and within different narrated and narrating events. Coding was necessary to show how verbal interactions are ordered and contribute to meaning making. Through analysis of the lived experiences of social actors, their voices and natural language get ‘anchored’ into a context to acquire their indexical meaning through stances.

Discursive cataloguing of solidarity through difference

The first excerpt is from my conversation with Shiko, this discussion reflects her life here as an immigrant woman and compares it with the life of African American women. She narrates the importance of life insurance and how it contributes to her construction of immigrant vs. native figures of personhood. To construct the US vs. Kenyan chronotopic frame, Shiko narrates their experiences as immigrant women. It highlights the gap in knowledge and experiences due to the spatiotemporal experiences they orient to. The following is an excerpt from my conversation with Shiko, an African woman from Kenya, in her late sixties. On the day of the conversation, Shiko invited me for dinner at her home on the outskirts of our small Midwestern college town. Shiko and I sat at a large wooden dining table while her twenty-six-year-old son prepared dinner. My little one, sixteen months old at the time, ran around as we talked. Most of the interviews and conversations were conducted in English, except for a few phrases and sentences in Kiswahili (Kenya's national language, which I translated). Shiko narrates her experiences and relationships with African American women. Her narration led to an explicit discussion of how these women differed culturally, and her understanding of how these differences were central to the construction of collective identities.

This excerpt illustrates how Shiko employs shifters (we/us/our vs. they/them) and deixis of verb tense, such as “we were talking about” (line 3), to invoke a past chronotopic frame in a narrated event to describe a conversation with African American women. Throughout this excerpt, Shiko invokes present and past chronotopic frames using spatial and temporal deixis (there-then vs. here-now) and shifters (such as we/us/our/they/them) to reference speakers and invoke different interactional contexts that they index. This narration enables Shiko to connect her experiences and mine in the immediate chronotopic frame, and her experiences and other African women in a narrated event. By contrast, she employs person deictics “they” in line 1 to construct African American women as ‘other’ in a past chronotopic frame. Through this narration, she constructs intersubjective links between herself, African immigrant women, African American women, and me in two different spatiotemporal orientations (Dubois Reference Du Bois2007; Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011; Koven Reference Koven2013).

In lines 1–8, Shiko employs an exclusive “we” deictic reference to refer to herself and other African women in a mini-narrated event that occurred in the past. This is to provide an example of the knowledge gap regarding the importance of purchasing life insurance and the perceptions of African immigrant women regarding acquiring life insurance, as she narrates in lines 1–5. She addresses the differences in the experience of purchasing life insurance as an immigrant and native-born. Consequently, African Americans are regarded as people without stress about life insurance. Shiko employs “we” in this excerpt to align more with African immigrant women in more immigrant-centered interactions.

In contrast, Shiko uses “they” to distance herself in the narrating event and other African immigrant women in the narrated event from African Americans in a more diasporic-centered interaction. In this narration, Shiko alternates between using the deictic reference we or we/us vs. they them to scale between the immigrant and native scale. She employs the shifter “we” in her statement, “we are not from this country” (line 8), to scale herself and other African immigrant women as immigrants and African American women as natives. Shiko invokes a chronotope of transnationalism (immigrant vs. native scale) within the narrated event to explain how being an immigrant can affect the lived experiences of diasporic subjects. As marginalized individuals, mobility destabilizes their initial sense of security and belonging, so they always have to be on the lookout in case of an eventuality. Their immigrant status, in this case, differentiates between the experiences of African immigrants and African Americans regarding life insurance. For African immigrant women in this particular case, purchasing life insurance is crucial in case there are any emergencies within their families, in the US or Kenyan chronotopic frame. There are some rules and stipulations governing the survival of immigrants in different visa categories in the US, namely, limited working hours and specific places in which one can work. Therefore, navigating life as an immigrant in case of an eventuality can be challenging, especially if one has a family.

In another interaction with Shiko, she encouraged new African students with families to obtain life insurance during a welcome party for new African students in the community. She narrated how her husband unexpectedly passed on a Sunday afternoon, leaving her a widow with four young children. At the time, she was still a student caring for her four children. Were it not for life insurance, she explained that she would not have been able to raise her children as an immigrant in the diaspora. Even though life insurance is essential for African American women, the extract suggests that it is not a priority for most African American women or African Americans in general (lines 7–8). This experience is not unique to African or African American women in this community.

Cultural/ethnic practices are another way the African immigrant women navigate differences in Kenyan vs. the US chronotopic orientations. Through the use of the deixis, Shiko employs some of the tactics of differentiation, specifically the tactic of distinction emphasized in Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz, Hall and Duranti2004) commentary, to scale ethnic and cultural differences in African women's experiences in the Kenyan chronotope and the US chronotope. In lines 14–22, she uses person deixis such as we/us/our vs. they/them to enact a quick scalar change (to take a distancing or aligning stance with other African immigrant women and African American women in the narrated event) about the social and cultural differences that emerge among African immigrant women and African American women during their interaction with each other in the US chronotopic frame. During her narration, Shiko invokes a chronotope of cultural/ethnic practices; more specifically, she illustrates cultural differences by recounting how, culturally, in Kenya, people are used to stopping by friends’ homes without a prior appointment or notification. In this interaction, Shiko narrates her own lived experience, being able to stop by a friend's house without making a prior appointment in the diaspora, which interacts with a higher scale that centers on culturally/ethnically specific practices. She further mentions that she had stopped at Achieng's house earlier, without initial notice (lines 17, 19). Shiko acknowledges that her cultural and social practices are different from African Americans and, in turn, respects the differences using person deictics “we” to reference me, herself, and other African women and “they” to reference African American women. The way Shiko applies the tactic of differentiation is arguably strategic; she applies it to invoke the chronotope of cultural practices, partly to explain some of the cultural aspects of Kenya's culture and how they differ from the diasporic cultural practices. This scaling practice helped Shiko orient herself to past and present chronotopic timescales. This construction echoes the notion of ‘scalar intimacy’ as conceptualized because her experiences in Kenya enabled her to orient to cultural and ethnic chronotopes (Pritzker & Perrino Reference Pritzker and Perrino2021). Shiko's recognition and understanding of difference are evident through her narration, “So I cannot expect them to understand that I am just showing up, you know that- … Because I am Kenyan, so that gap is still gonna b::e the::::re because of the way we were brought up and the way they were brought up” (lines 21–25). Her recognition of these differences enables her to construct an alignment with African American women by showing her understanding of the cultural/ethnic differences between African immigrant women and African American women when visiting one another in the post-migration context. Despite the difference in their pre-migration Kenyan chronotope (there-then) and the US chronotope (here-now), Shiko and the women can construct solidarity through differentiation. This construction is not read as distance among the women because the African immigrant women employ the lower scale to invoke the difference in experience among non-native immigrants and natives and employ the higher scale to link these images to different cultural and ethnic practices in the US chronotope. This enables the social actors to invoke their lived experiences and ‘culturally situated’ experiences in their interactions but not in a way that creates disalignment/distance. The women create a unique solidarity by acknowledging their cultural backgrounds from different spatiotemporal conditions and contexts.

After identifying the differences between African immigrant women and African American women in the narrating and narrated events, Shiko agrees that a gap in knowledge and cultural differences will never cease to exist among the African immigrant women and African American women (lines 32–35). They have learned to live with and understand each other in the immediate chronotope despite their differences that stem from their experiences living in the US and Kenyan chronotope in different spatiotemporal orientations. This conversation topic came up during a women's biweekly fellowship. They all agreed that even though there are and will continue to be differences in their practices (social and cultural) due to how they grew up, where they grew up, and how they were brought up, this did not prevent them from interacting or building communities. Even though they employ the deictic pairs we/us vs. they/them, these women's conversations about differences are complexly performative, in that they do not speak of their incompatibility, but seem to contribute to a kind of transnational feminist community building, following Mohanty's (Reference Mohanty2003) definition of solidarity, where diversity and differences are foregrounded, acknowledged, and respected. Shiko takes an affiliative stance in the narrating event towards African American women in the narrated event by saying, “Now we are like them, and they are like us” (line 33). This performance shows that the women choose to stay and relate, as Shiko narrates in lines 38–41, “But one thing I appreciate about African Americans in this country is that ↓we are standing on their shoulders. If it weren't for them, doing the groundwork for us to come and be accepted somehow, it would never have worked for us”. Shiko's differentiation does not adopt a distancing stance against African Americans but bears a positive and relational meaning (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). Here, the women employ the deictic pair we/us to construct solidarity to anchor their group experience in the US chronotope in the immediate place and time. To perform solidarity, Shiko makes a scale jump from a local scale, where she narrates her relations with other African American women, to a translocal scale, where she narrates how African Americans, in general, have laid the groundwork for Africans to arrive and be accepted. The “groundwork” Shiko refers to is not only about identity (lower scale) but also reflects the structures of oppression in terms of race, gender, class, and citizenship that these women and other Black subjects identify with and the history behind it (higher scale; lines 38–41). The African body is usually rendered slaves, which makes them susceptible to structural and institutional racism, which is how African people are positioned. She invokes solidarity here by using deixis we/us to collectively reference Africans and African Americans. In the narration above, the participants’ imagined experiences enabled them to position themselves as subjects in the diasporic spaces, by narrating some of their own experiences in the diaspora, and how they navigated oppressions and institutional racism as constructed through the media, and news before they moved to the US. The images that were put out by the media did not encompass the lived experiences of African Americans. Therefore, when African immigrants move to the US, they realize why African Americans react the way they do. This community building is not only about identity construction or building solidarity but also forming a community to survive, which is made possible when culturally situated ideas interact with participants’ lived experiences to enable this construction of difference and community building, which fosters survival in the diaspora. These women's discourses explore differences and bring identities and social experiences situated in the historical, cultural, and social contexts in which the interlocutors’ conversations emerge to encourage a kind of ‘black heterogeneity’ (Smalls Reference Smalls2015).

Solidarity through reorienting stereotypical differences

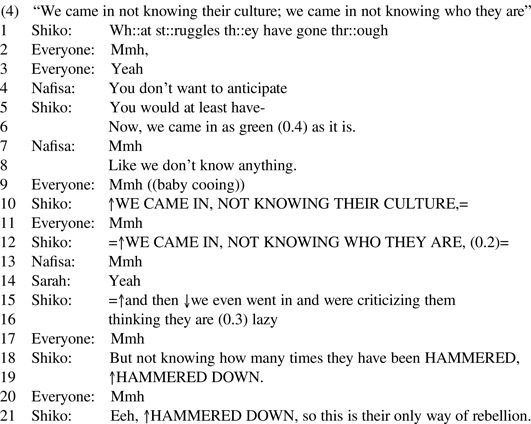

Excerpts (4) and (5) are from my conversation with the four women I call Sarah, Shiko, Achieng, and Nancy in a naturally occurring conversation on a Saturday evening at Achieng's house. In these excerpts, the African immigrant women are reflecting on some of the stereotypes they heard or believed about African Americans prior to moving to the US. Later in the conversation, they turned their focus on their post-migration, where they talked about how their perception of African Americans has shifted, and this is partly because of their experiences as a Black and African immigrant woman in the US. On the day of the interview, Achieng invited us to dinner, and when my little one and I arrived at 6:30 pm, dinner was ready and set on a small side table beside the main table. The four women were gathered around the main table and conversing when I arrived. I joined them, and we continued talking before serving and eating. Our conversation quickly led to a candid discussion about African immigrants’ perceptions of African Americans before they moved to the US. Similar to my conversation with Shiko, the women employed the person deixis clusters we/us/our (inclusive/exclusive) to refer to African women and African immigrants in the US, and they/them to reference African American women. The narrations illustrate how they constructed differences not to distance themselves from their African American counterparts or reiterate the stereotypes they may have had about African Americans before migrating, but rather to denaturalize these stereotypes.

In the extract above, the narration illustrates the women's shift from a local scale (pre-migration) to a translocal scale (post-migration) in the narrated event to take different stances regarding some of the stereotypes and beliefs they had about African Americans before moving to the US. The women use we/us to reference themselves, me, and African immigrants in the narration event to align more with Kenyans’ pre-migration Kenyan chronotope. They use they/them deixis to reference African Americans in general in the narrated event, which invokes a US chronotope. To invoke a translocal scale, the women repeatedly use deictic terms such as “came in” and “went in” (lines 10, 12, 15) to index directionality and mobility, such as entering a place and using past tense verbs to demonstrate that something happened in the past, construct their ‘transnational identity’, as well as invoke a past chronotope. In line 6, Shiko employs the metaphor “green” to refer to the African immigrants’ state as they enter the US. This metaphor is typically used to depict newness. This shows how, when Kenyans enter transnational contexts as immigrants, they are generally not conversant with the socioeconomic and political realities of Black subjects in the US; hence, greenness in this context depicts a state of newness to a place, as Shiko narrates in line 6.

As migrants, even though they had just arrived in the US, they applied stereotypical views of African American figures of personhood to evaluate African Americans as lazy. Throughout the narrated event, the participants invoked a more collective scale to adopt an affiliative stance using referential deixis such as we/us/our (lines 1, 6, 10, 12, 14) to reference African immigrants in a pre-migration chronotope. Collectively, the women's interactions are oriented toward constructing differences in a way that denaturalizes rather than essentializes them. The African immigrant women deconstructed some of their views on African Americans because of their lived experiences and interactions in North America's African diaspora. Their backgrounds as Kenyan women and immigrants in the US and their lived experiences enabled them to construct differences and establish a presumed alignment with one another. Their conversations showed that some of their stereotypes about African Americans arose because they did not consider African Americans’ social, political, or historical experiences. They employed the deictic reference they/them to construct African Americans as others in the US chronotope. Through their repeated use of person deixes, such as we/us and they/them, they invoke relations with other African immigrants as the foreground pre-migration experiences in Kenyan chronotope and some of the essentialized views about African Americans, and how these stances have changed over time.

In excerpt (5), lines 22–24, we see the assertion that pre-migration, most Africans applied the evaluative indexical “lazy” to construct a racialized figure of personhood (Agha Reference Agha2005), ‘an African American’. The African immigrant women link the image of the racialized figure of personhood with laziness and the inability to work and survive in the US chronotope. They narrate that, as African immigrants, they enter the diasporic space with preconceived notions about African Americans, they criticize them, and call them lazy. In another conversation with a group of African Americans, they had similar stereotypical views of Africans based on what was shown to them in the media. In these discourses, Africans were evaluated as primitive before meeting and interacting with them. On a local scale, Africans construct the racialized figure of personhood as ‘lazy’, as mentioned above. However, on a translocal scale, when African immigrants are ‘constructed’ and ‘made black’ through the social imaginary (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999), this makes them susceptible to many of the same racial violence suffered by African Americans. The women employ a shift in stance from a local to a translocal scale to deconstruct the racialized figure of personhood and reconstruct it as ‘hardworking’ and ‘persevering’. Shiko shifts her focus to her own experience in the immediate chronotope being a Black woman at work and experiencing racism, as she narrates in her bold statement, stating that “I feel these days, even me, I just wanna rebel. hhh.” (line 26). Shiko shifts from a lower scale, where, through their lived experiences in the Kenyan chronotopic, she constructed the African Americans as ‘lazy’, to a higher scale, where she relates to the way race and racialized subjects are constructed through institutional and structural racism in the US chronotropic frame. In the US chronotope, Shiko and other African immigrants are constructed within the same evaluative indexical ‘lazy’ she held in the pre-migration Kenyan chronotope. She de-essentializes the evaluative indexical ‘lazy’ and reconstructs it as a way of rebelling against oppressive systems. All of the women in the narrated event align with Shiko in solidarity (as shown in lines 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 37, 39, 41, 43, and 45). Shiko's experience as an African immigrant and a Black woman in the US enables her to reconstruct the evaluative indexical ‘lazy’ as a way that African Americans resist the oppressive systems in the US, even though she shifts between the use of person deictic reference we/us/our to take an affiliative stance and they/them to construct African Americans as others. This performance is not distancing but builds community by consciously recognizing their pre- and post-migration experiences and relations (Mohanty Reference Mohanty2003; Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). They seem to recognize their shared positions (with African Americans) under structures of oppression, enabling them to build solidarity. To that end, the women's construction of difference is not to emphasize the stereotypes they held about African Americans before migration but to denaturalize the stereotypes to construct solidarity and align with African Americans.

Solidarity through shared struggles and learning

This last excerpt is from a casual conversation with Shiko, Achieng, Juma, Nafisa, and Sarah, all from East Africa. They narrate how, as African immigrants, they do not consider the experiences of African Americans and how they affect their own experiences as Black immigrant mothers in the diaspora. Shiko believes that African immigrant women are supposed to be aware of the systemic and institutional racism that African Americans experience. She sees the need to shift from being “green” because, in the US chronotope, their children are constructed and seen as Black. Therefore, they need to educate themselves and view the struggles of African Americans as their own. This exchange occurred during a dinner invitation to Achieng's house. Juma, Achieng's husband, was the only male in the conversation, but he drifted in and out throughout the conversation because he was grilling some goat meat outside. During dinner, Sarah expressed concerns about something that was bothering her daughter. Although unsure, she suspected that her daughter was being bullied. This incident about Sarah's daughter led to a conversation about women's challenges in mothering their children in the US. The women expressed a gap in the knowledge and awareness of African Americans’ cultural, social, historical, and political backgrounds, which can immensely affect how they parent their children. However, this knowledge gap does not distance African women from their African American counterparts. Instead, it helps them build a form of solidarity in which they can learn from each other.

The conversation starts with the women discussing how they were raised, which differs from how they would raise their children in the US. Here, Shiko employs the person deictics “we” and the temporal deictic “were” to depict a past chronotope and a lower scale to reference the experiences of African immigrant women. Her reference to this past chronotope (there-then) is essential because it affects how they raise their children (here-now) in the African diaspora. After living in the US for over thirty years, she acknowledges that her eyes have opened. She notes that Black immigrants experience the same challenges and oppression as African Americans. She uses the deictic pair we/their repeatedly to construct herself and the other women in narrating events and African Americans in the narrated event, but not in ways that engender struggles and oppression but to highlight their experiences in the pre-migration and post-migration experiences (see lines 74–75: “UNTIL WE SEE THEIR STRUGGLES UNTIL WE -we are not educated, WE ARE NOT EDUCATED.”). When some African immigrants move to the US, they do not identify or associate themselves with Blackness; however, as they work and bring up their children, they accumulate memory and experience and subsequently ‘become’ Black (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1999; Asante Reference Asante2012).

In lines 78–80, when they (African immigrants) moved to the US, they were “green”, meaning they did not fully understand how institutional and structural power structures oppressed African Americans. After staying in the US for a while, they find it crucial to talk about race in their homes (family chronotope) because this will educate them on how to survive in the US chronotopic frame. They suggest that they must start seeing Black and African Americans’ struggles as their own. This topic is frequently discussed among African immigrant women because women in most Black communities are culturally bestowed the roles of family caretakers or educators, or tasked with being role models for their children. Therefore, the education they offer their children about survival is a source of empowerment, socially and empirically, and can aid in the continuity of Black communities. Shiko builds solidarity in line 76 by aligning with African American struggles against obstacles to survival, white supremacy, and violence.

As Shiko states in lines 74–75, African immigrant parents and mothers should consider and embrace African Americans’ struggles as their own. Although subjects enter the discursive space with a range of cultural, social, and political views here and now, they are viewed and treated as Black. Thus, they must learn about African Americans’ racial history in the US to raise their children effectively. The women's identity construction is informed by both their cultural practices, institutional power structures (higher scale), and pre-and post-migration lived experiences (lower scale), which shows that ‘society is not an organic totality’ (Collins Reference Collins2019:233). Learning and understanding African Americans’ lived experiences (lower scale experiences) interacts with their ability to care for their children in the African diaspora by forming mothering networks (larger scale structures) to educate their children. These are essential and integral to building Black feminist solidarity. Collins (Reference Collins2019) stated that Black women's leadership in Black communities helped people survive, grow, and reject anti-racism practices, the cornerstone of Black feminist solidarity building. Educating children to survive within Black civil society or communities is integral to building feminist solidarity.

Conclusions and implications

This article explored how African immigrant women employ scaling practices and stance-taking through adverbial deixis to analyze their interactions, and how they negotiate and construct differences in the US diaspora. The data I present represents the women's pre- and post-migration experiences, making my analytical tools (scale, scaling, chronotopes, and stance) crucial for organizing and understanding my participants’ social positionings. This study specifically demonstrates that the women's experiences and interactions are chronotopically ordered, as is evident from the various scaled chronotopes in the data. To take a different stance, the women invoke global scale chronotopes to discuss some of the stereotypes they previously held about their African American counterparts and a more local scale to reference their own lived experiences in the diaspora; they prompt a reorientation to the ways they construct the racialized figure of personhood. Women employ different deixes—such as we/us/our, spatial here/there, and temporal now/then—to reference themselves and other African women in both narrated and narrating events, as they invoke both local and trans local chronotopic images and timescales.

This research highlights the experiences of African immigrant women in the African diaspora by exploring how these women construct their identities. Through a nuanced examination of the lived experiences of African immigrants, the analysis shows that women's construction of solidarity goes beyond women's identity construction as stemming from similar experiences or origins; a careful investigation reveals that identities are scalar and chronotopic. In this research, solidarity is achieved by acknowledging differences when local scales intersect with translocal scales in the diasporic setting (excerpt 1) while employing deictic references to invoke different social types in the narrated and narrating events. From the women's interactions, it is evident that in some cases, solidarity is accomplished through meaningful differentiation, wherein the women recognize, acknowledge, and understand differences in their lived and imagined chronotopes rather than conflating or ignoring the differences between them, which is an example of feminist solidarity. Differentiation disrupts the notion that solidarity is synonymous with sameness or that differentiation always indexes difference/distance, as illustrated in the excerpts. The distinction these women make in their interactions aligns with Crenshaw's (Reference Crenshaw1989) theorization of identity, which accounts for differences among groups because the elision of difference is a problem and often leads to violence or tension among groups.

Theoretically, this interrogation illuminates differentiation and solidarity within multiethnic Black communities. This article has implications for the academic understanding of identity construction among African immigrant women, African immigrants in general, and other Black subjects in the African diaspora and marginalized communities by demonstrating how a group of Black women construct individual and collective identities through ‘discourses of difference’ rather than through discourses that simplify experiences of Black people and immigrants as homogeneous. It shows the complex sets of cultures, histories, languages, social practices, and social actors that comprise the African diaspora.

Appendix: Transcription conventions

- =

latched speech. The second speaker followed the first speaker with no discernable silence between them.

- ::

prolongation or stretching sounds

- ↑

sharper rises in pitch

- ↓

sharper falls on the pitch

- word-

cutoff or self-interruption

- CAPS

stress either by increased loudness or higher pitch

- [ ]

overlapping

- (())

analyst comments and descriptions

- (.)

micropause

- hhh

laughter

- (0.4)

time pause