INTRODUCTION

Globalization leads to paradoxical pressures within multinational enterprises (MNEs) both to standardize and localize corporate strategies (Chung, Bozkurt, & Sparrow, Reference Chung, Bozkurt and Sparrow2012; Evans, Pucik, & Björkman, Reference Evans, Pucik and Björkman2011). Translating strategies from corporate to subsidiary locations can therefore be challenging (Biggart & Guillén, Reference Biggart and Guillén1999; Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006), especially when the subsidiaries are located in emerging economies (Beamond, Farndale, & Härtel, Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016; Corredoira & McDermott, Reference Corredoira and McDermott2014; Dong, Yu, & Zhang, Reference Dong, Yu and Zhang2016), highlighting the need for us to better understand how firms handle this process (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2012). To understand the extent to which contextual factors (‘frames’) affect key organizational actors when translating corporate strategies to subsidiaries in emerging economies, we bring together complementary insights from the translation (Czarniawska & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005) and talent management (Farndale, Scullion, & Sparrow, Reference Farndale, Scullion and Sparrow2010) literatures.

Translation is the continuous circulation of management ideas and practices where the original concept evolves as it moves around the firm and is converted into new ideas (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2009, Reference Czarniawska2012; Czarniawska & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005; Siek, Reference Siek2015). How the translation process occurs is through a series of frames and actors. A frame is an emergent story that is tested, developed, and elaborated (Czarniawska-Joerges, Reference Czarniawska- Joerges2004) and subsequently used by actors to interpret what is happening around them (Goffman, Reference Goffman1974). Frames can be either socially-shared or culture-specific (Rettie, Reference Rettie2004), the latter referring to local environmental differences that may affect translation (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2012). However, a theoretical understanding on how local frames affect key actors when translating corporate strategies to emerging economies is lacking. Drawing from the field of strategic management, we explore the translation process specific to talent management strategy in an Australian MNE operating in Latin America. Corporate talent management (CTM) strategy guides activities designed to attract, identify, develop, and retain individuals considered to be talented employees (Meyers & Van Woerkom, Reference Meyers and Van Woerkom2014). Diffusing CTM strategies into new locations with different cultural and societal contexts may lead to divergent outcomes if the strategy does not fit the receiving society (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006; Czarniawska & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005; Djelic & Quack, Reference Djelic, Quack, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin-Andersson2008).

A macro view of CTM strategy formulation and implementation has mostly been absent in the literature (Huselid & Becker, Reference Huselid and Becker2011). This involves exploring the translation processes between corporate and subsidiaries through the different frames that emerge at the national level (Edwards & Kuruvilla, Reference Edwards and Kuruvilla2005). Translation takes place between different operating sites as well as between different actors inside organizations. We therefore focus on exploring differences between sites across countries (Peru, Chile, Argentina) as well as across different sites (urban and rural) within countries. As it has been argued that a better understanding of the interaction between frames and actors may assist MNE localization (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002), we explore how well local actors understand local frames relative to local acceptance and corporate intention (Glover & Wilkinson, Reference Glover and Wilkinson2007; Thite, Wilkinson, & Shah, Reference Thite, Wilkinson and Shah2012).

To explore these dimensions of talent management strategy translation, we conducted an in-depth case study in three Latin American countries. The emerging economies of Latin America (Newburry, Gardberg, & Sanchez, Reference Newburry, Gardberg and Sanchez2014) are an ideal setting due to its high levels of foreign MNE activity (particularly in the mining sector). Moreover, Latin America differs substantially in terms of language and culture from the home country of the MNE studied here, Australia (Maloney, Manzano, & Warner, Reference Maloney, Manzano and Warner2002). The Latin American region suffers acute talent shortages (Newburry et al., Reference Newburry, Gardberg and Sanchez2014), especially in the more remote rural locations where mining companies are most active (Aedo, Walker, & World Bank, Reference Aedo and Walker2012), making talent management a critical corporate activity. Specifically, we focus on Peru, Chile, and Argentina, which remain poorly understood with regard to talent management as what little research there had been in Latin America to date has mostly focused on Mexico and Brazil (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2007; Fischer & Galvão de Albuquerque, Reference Fischer and Galvão de Albuquerque2005; Tanure & Duarte, Reference Tanure and Duarte2005; Zadia, Reference Zadia2001).

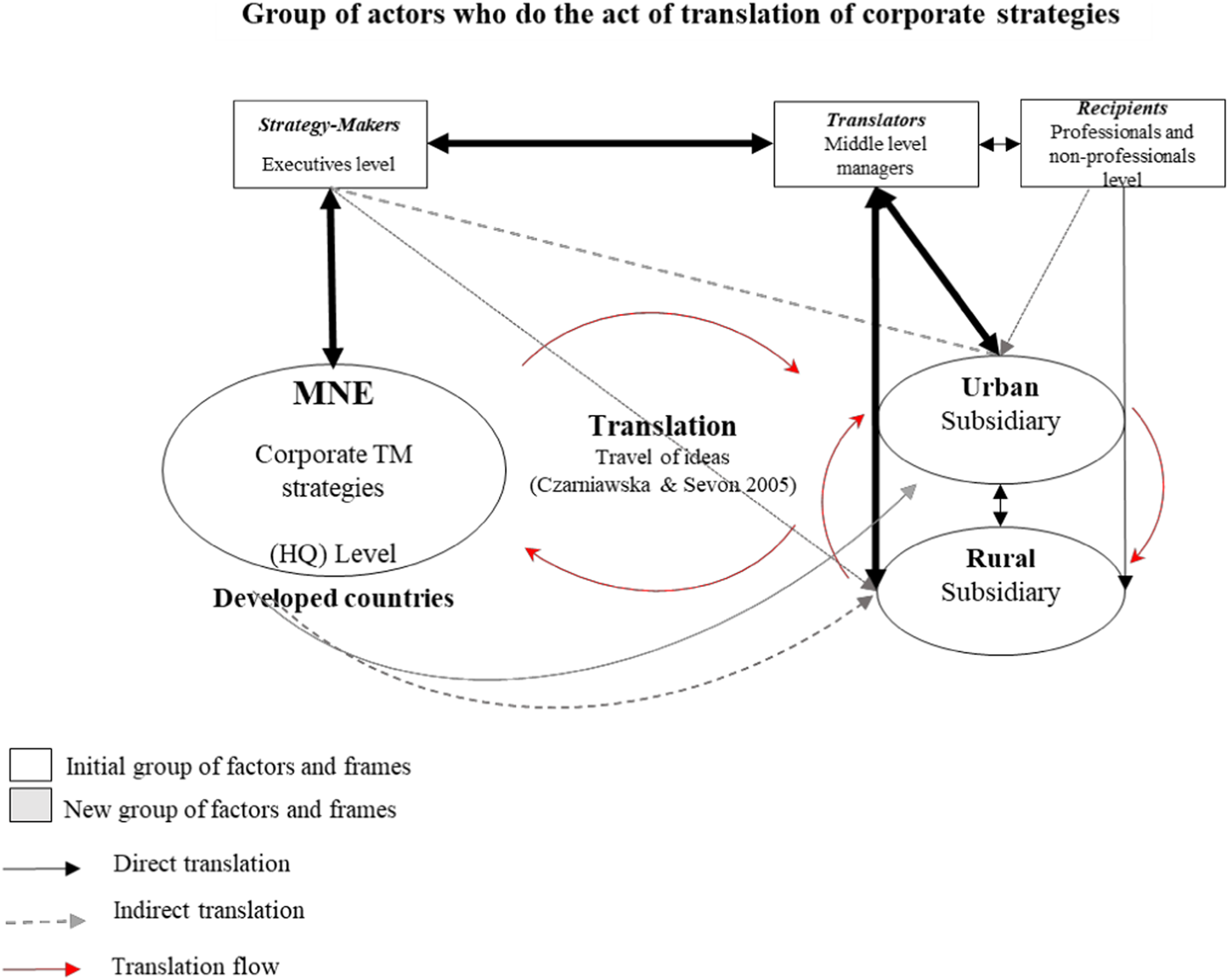

This research contributes to understanding the effect of frames on actors underlying the translation process from corporate to subsidiary in emerging economies. We address the lack of research on macro-level factors affecting talent management (Khilji, Tarique, & Schuler, Reference Khilji, Tarique and Schuler2015) as well as the need to balance talent management strategies between global integration and local responsiveness (Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen, Ehrnrooth, & Mäkelä, Reference Björkman, Barner-Rasmussen, Ehrnrooth, Mäkelä and Sparrow2009; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Pucik and Björkman2011; Farndale et al., Reference Farndale, Scullion and Sparrow2010). We do this first by contributing to the literature on translation by proposing three initial core sets of actors as instrumental in the translation process (strategy-makers, translators, recipients). Second, we identify four initial frames (community relations, humanism, diversity, skill scarcity) particularly pertinent to the Latin American context for this area of practice based on a thorough literature review. Third, we combine the actors and frames to present an overview of the translation process based on 76 in-depth interviews. In addition, the findings revealed (i) additional (internal and external) frames not yet identified in the literature on Latin America, and (ii) new actors (long term and community relation employees) specific to the translation process in Latin America. In the following sections, we present an overview of the extant translation and talent management literatures, before describing the empirical study undertaken and its findings.

FRAMES: TRANSLATION AND TALENT MANAGEMENT

Translation is the travel of ideas using frames as categories of plots to associate separate episodes or to explain time and narrative when telling stories (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska- Joerges2004, Reference Czarniawska2008, Reference Czarniawska2012). Based on an extensive review of extant literature (including: Beamond et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016; Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2012a, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b; Härtel & Fujimoto, Reference Härtel and Fujimoto2014; Johnsen & Gudmand-Høyer Reference Johnsen and Gudmand-Høyer2010; Kemp, Reference Kemp2004; Pirson & Lawrence, Reference Pirson and Lawrence2010; Ransbotham, Kiron, & Prentice, Reference Ransbotham, Kiron and Prentice2015; Szablowski, Reference Szablowski2002; Vaiman, Scullion, & Collings, Reference Vaiman, Scullion and Collings2012), four frames emerge as particularly pertinent to CTM strategy translation in Latin America: talent scarcity, diversity, community relations, and humanism. We describe each of them below.

Talent scarcity

For a firm to sustain its competitive advantage, it creates, extends, updates, protects, and retains its unique talent resource base (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Teece Reference Teece2007). Such talent remains scarce (Ransbotham et al., Reference Ransbotham, Kiron and Prentice2015). Firms need to understand and address talent scarcity through their strategic capabilities, organizational infrastructures, and strategic needs of local operations to balance global integration and local responsiveness (Sparrow, Reference Sparrow2012). This is particularly true in Latin America (Newburry et al., Reference Newburry, Gardberg and Sanchez2014) where, although there is a large and youthful population in the region, firms still struggle to find skilled talent to develop expansion opportunities (Aedo et al., Reference Aedo and Walker2012; The World Bank, 2017; World Economic Forum, 2017).

Community relations

As part of corporate social responsibility (CSR), community relations refer to ‘work that involves facilitating and/or managing relationships and interaction between [operations] sites and local communities’ (Kemp, Reference Kemp2004: 1).

Community relations as an institutional mechanism that affects decision-making at the subsidiary level, especially in rural areas of emerging economies where a need to maintain effective community relations persists (D'Amato Herrera, Reference D'Amato Herrera2013; Jackson, Amaeshi, & Yavuz, Reference Jackson, Amaeshi and Yavuz2008; Tymon, Stumpf, & Doh, Reference Tymon, Stumpf and Doh2010). In Latin America, local community members are ‘silent’ stakeholders in a firm's operations (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b), where there is increased social risk for the viability of projects if firms are considered socially unacceptable by communities (Joyce & Thomson, Reference Joyce and Thomson2000).

Demands from indigenous groups in Latin America are often consequential, particularly when these groups are marginalized by their respective governments (D'Amato Herrera, Reference D'Amato Herrera2013; Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b). For example, MNEs often experience land ownership disputes with indigenous and community populations (comuneros) in Peru, needing to balance this against obtaining a social license to operate (Härtel, Appo, & Hart, Reference Härtel, Appo, Hart, Ferdman and Deane2013; Muradian, Martinez-Alier, & Correa, Reference Muradian, Martinez-Alier and Correa2003; Nelsen, Reference Nelsen2009). Receiving societies thus may perceive corporate strategies as foreign and try to defy translation (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006). CTM strategy may include hiring regional people and instituting community relations programs as part of maintaining a social license to operate through ‘investment in community goodwill’ (Szablowski, Reference Szablowski2002: 259).

From a cultural perspective, trusting social relationships are critical in Latin America (Elvira & Davila, Reference Elvira and Davila2005b). From an institutional perspective, the communities in the region and in rural areas are often unskilled, vulnerable, and poor, with local dialects, an absence of government protection, and where indigenous communities frequently clash with non-indigenous communities (Gifford, Kestler, & Anand, Reference Gifford, Kestler and Anand2010). MNEs that classify subsidiary employees in emerging economies as subjects (rather than objects) with unique characteristics (Gallardo-Gallardo, Dries, & González-Cruz, Reference Gallardo-Gallardo, Dries and González-Cruz2013), and understand that local talent needs to be developed rather than acquired (Dries, Reference Dries2013) are more likely to be successful in the translation of corporate strategies (Beamond et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016). A MNE's local social license to operate can be severely affected if it does not understand these frames and does not offer significant local community support (Gifford et al., Reference Gifford, Kestler and Anand2010).

Humanism

Johnsen and Gudmand-Høyer (Reference Johnsen and Gudmand-Høyer2010: 332) highlight a need to ‘maintain the humanity of the subject of human resources (HR) management by exposing the inhumanity of the managerial prescription’. This is the essence of humanism: blending value models by integrating the economic system and its humanistic roots (Pirson & Lawrence, Reference Pirson and Lawrence2010). In Latin America, humanism is an important frame to consider when building alliances with the community based on trust and respect for the social contract, which endows organizations with the license to operate (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2012a). Davila and Elvira (Reference Davila, Elvira, Davila and Elvira2009) also suggest that a new humanist leadership approach is required in Latin America to balance more individual and economic organizational perspectives prevalent in the West.

They suggest that this new humanism fits the Latin American culture because the individual is valued as part of the collective, i.e., at the center of the organization and society (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila, Elvira, Davila and Elvira2009).

Diversity

Workforce diversity includes all aspects that make employees different including race, age, culture, gender, disability, and religious beliefs. Workforce diversity has dramatically increased due to the globalization of trade, legal and moral stances on diversity, and an increase of women in the workforce (Härtel & Fujimoto, Reference Härtel and Fujimoto2014). However, the impact of workforce diversity varies among countries. In Latin America, diversity is geographically and ethnically embedded (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2012a) and is an essential component of management practice. In addition to workforce diversity, the region encompasses multiple types of organizational and socio-economic or political diversity, including organizational ownership arrangements, management practices, the meaning of family, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic contexts (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b). For example, family is seen as a priority, and some companies employ family members to ensure trust, loyalty, and responsibility (Elvira & Davila, Reference Elvira and Davila2005a).

In summary, the four frames are narratives that affect local translation of CTM strategies. Each frame can be perceived differently by the different actors involved in translating corporate strategies, redefining and interpreting them according to the context in which they are located (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006; Djelic & Quack, Reference Djelic, Quack, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin-Andersson2008). In turn, depending on how actors translate corporate strategies, this may either increase or decrease the chances of local societies accepting the strategies (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006).

ACTORS IN TRANSLATION

Each act of translation requires agents (or actors) for the act of transformation (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2009). A practice (in this case a CTM strategy) cannot travel intact as it must be simplified and abstracted into an idea for the transfer to take place (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2012). These ideas then travel across the globe, whereupon they are locally received and interpreted. Identifying the key actors in this translation process is a complex task, and we argue that this likely varies for all MNEs due to different organizational structures, systems, and relationships. In general, however, top-down and bottom-up knowledge inflows in a MNE from persons at higher hierarchical levels who influence middle and first-line managers’ exploration and exploitation activities (Mom, Van Den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Mom, Van Den Bosch and Volberda2007). This higher hierarchical level is responsible for the entire organization including defining strategies and setting organizational goals (Samson & Daft, Reference Samson and Daft2015). As our focus is on MNEs, we explore actors from three generic levels akin to many corporate structures: corporate headquarters (HQ), regional head offices, and host-country operations. Following this logic, we propose three core sets of actors as instrumental in the translation process: strategy-makers, translators, and recipients.

Strategy-makers

In translation, strategy-makers’ cognitive evaluations of a situation are shaped by prior ideology that in turn shapes beliefs about action choices (Child, Reference Child1997). The social structuring of environments thus either enables or constrains strategic choice (Whittington, Reference Whittington1988). Strategy-makers include managing directors, chief executive officers, vice-presidents, and general managers, who manage the attainment of the overall organizational goals (Samson & Daft, Reference Samson and Daft2015). In addition, shareholders also have a direct impact on decision-making (Hitt & Gimeno, Reference Hitt and Gimeno2001; Wang, Musila, & Chowdhury, Reference Wang, Musila and Chowdhury2005). We might expect them to have different institutional and cultural perceptions on frames than managers working in the emerging economy subsidiaries. These differences result from dissimilarities in cultural values, institutionalized norms, and the distance between home and host-countries (Clark & Lengnick-Hall, Reference Clark and Lengnick-Hall2012). Any talent management strategy therefore must balance the corporate MNE reality (in terms of a declining or growing market) with the subsidiary's labor market reality (the availability of necessary talent). This situation is exacerbated when operating in subsidiary rural, ethnic locations far from subsidiary urban areas where skills are less likely to be available (Jara, Perez, & Villalobos, Reference Jara, Perez and Villalobos2010).

Translators

Translators act as agents on behalf of strategy-makers to transfer CTM strategies to other organizational levels. While strategy-makers focus on attaining the overall organizational goals through planning, organizing, leading, and controlling resources (Samson & Daft, Reference Samson and Daft2015), translators or managers from subsidiaries at the regional or country level assume the task of mediating, being a catalyst and leading knowledge exchanges, developing and maintaining linkages with organizations (Hedlund, Reference Hedlund1994; Tippmann, Sharkey-Scott, & Mangematin, Reference Tippmann, Sharkey-Scott and Mangematin2014), and interacting with peers across geographic boundaries (Ghoshal, Korine, & Szulanski, Reference Ghoshal, Korine and Szulanski1994). Translators must consider both the global institutional factors embedded in the corporate business strategies (e.g., a growth market), as well as translating the corporate ideas in line with regional or local institutional factors (e.g., talent scarcity) (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008; Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002; Samson & Daft, Reference Samson and Daft2015).

Recipients

Any idea or strategy that is moved by translators from one place to another cannot reappear unchanged (Czarniawska, & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005), ultimately impacting how it is received. While strategy-makers may ask translators to transfer CTM strategies to other organizational levels, the recipient, here a first-line manager, carries out the final level of translation (to the workforce). This relates to translating the strategy directly to the local context: ‘in the light of his own beliefs and value system as well as his socio-cultural environment which may be rooted in a different or parallel history’ (Archibald, Reference Archibald, Garzone and Sarangi2007: 165). Line managers internalize ideas by converting them to practice (Hong, Snell, & Easterby- Smith, Reference Hong, Snell and Easterby-Smith2009), adapting them to respond to local, context-specific needs (Saka-Helmhout, Reference Saka-Helmhout2010). More specifically, host-country national managers may have idiosyncratic cultural and educational differences even within a single country, making dissemination and reception of corporate strategies even more complex (Beamond et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016).

In Latin America, it is argued that there is considerable inconsistency between the strategies developed by well-educated managers and how they are perceived by the local workforce (Elvira & Davila, Reference Elvira and Davila2005b; Martínez, Esperança, & de la Torre, Reference Martínez, Esperança and de la Torre2005). Additionally, when subsidiaries conduct business activities in cities as well as rural areas, culture, and sometimes language, can differ across locations (Beamond, et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016), further affecting the recipients as they do not know or do not value foreign managerial practices (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006). Hence, actors may construct path dependency between corporate and subsidiary as part of their translation process (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006). Because pressures from local and community social structures affect the translation of ideas into actions (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2008), an understanding of the target audience (recipients) is likely to be critical.

In summary, differentiating and connecting across the three groups of actors, strategy-makers (executives) act as the source, producing the relevant strategy, while recipients (line managers and workforce) are the target, at the level where strategy needs to be implemented. Translators (middle managers) mediate between the source and the target, potentially having the most complex role with the need to understand both the source and target contexts (Archibald, Reference Archibald, Garzone and Sarangi2007). In searching for meaning, translators connect separate episodes to interpret frames, to explain first to themselves, and then to transfer these strategies to others (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2008) re-creating new frames. Recipients may receive, understand, and accept these strategies if they are embedded in these frames, but if not, they may remain as foreign ideas (Archibald, Reference Archibald, Garzone and Sarangi2007). Subsequently, strategy translation may be lost in travel between an Australian MNE's corporate offices and subsidiaries in Latin America.

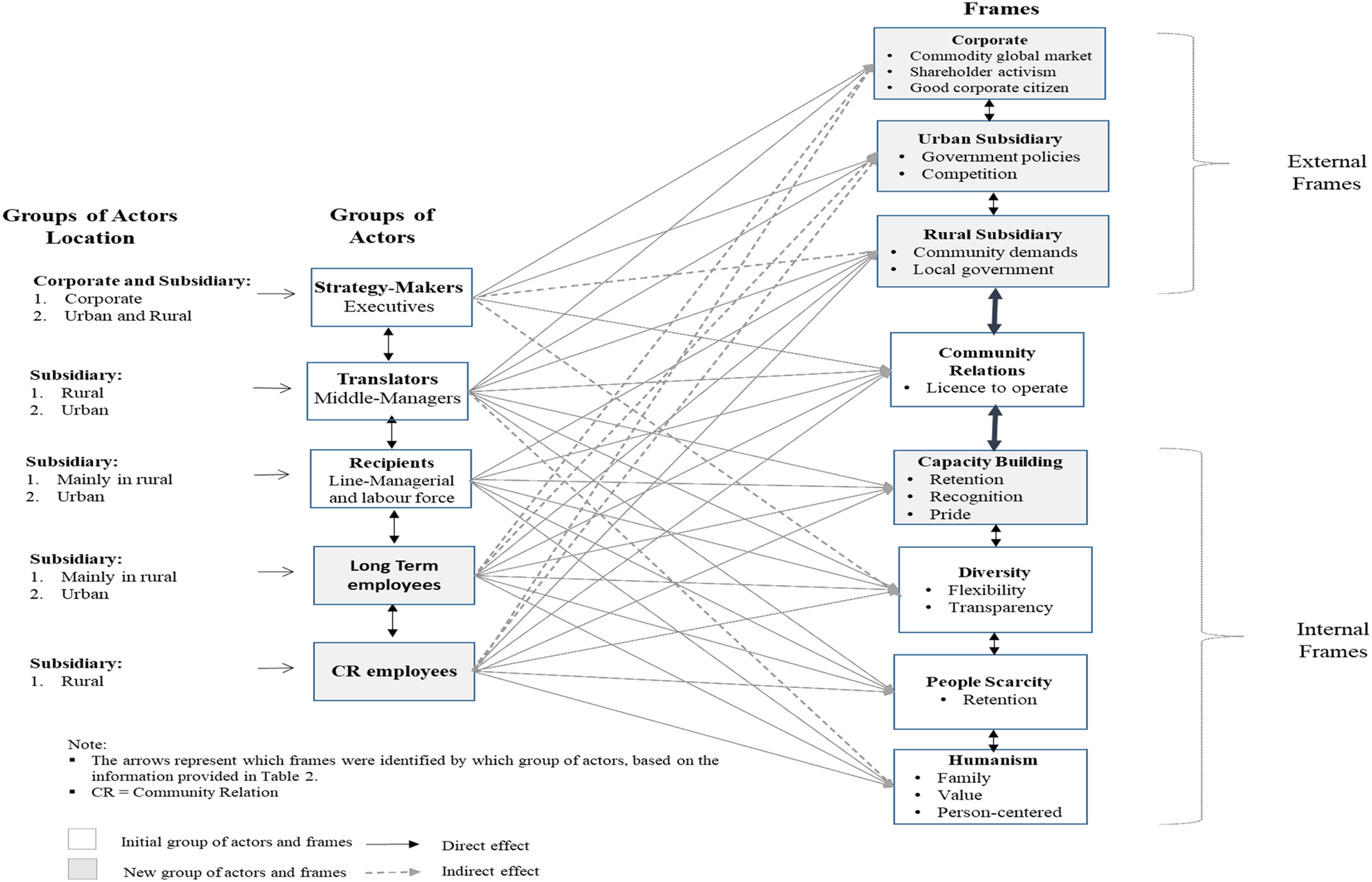

We have argued that four frames (skill scarcity, community relations, humanism, and diversity) are relevant when translating CTM strategy to local subsidiaries in Latin America. Moreover, we have posited that there are three groups of actors involved in the translation process (strategy makers, translators, and recipients). Figure 1 brings together the frames and actors to represent the guiding framework for the empirical study we now present.

Figure 1. Groups of actors and frames

METHODS

Research Design

This research uses qualitative techniques to understand the interaction between the frames and actors involved in the translation of CTM strategies. The case study research method is adopted to retain ‘the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events’ (Yin, Reference Yin2009: 4). Building on Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña's (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014) pragmatic realism, this study falls between tight pre-structured and loose qualitative designs for when ‘something is known conceptually about the phenomenon, but not enough to house a theory’ (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1984: 27). In conducting the literature review, we sought discipline-specific concepts (the four frames and the three actor groups) to map what would be investigated empirically (Yin, Reference Yin2009).

Because this research involves different national contexts that vary in terms of cultural and institutional factors, ethnographic observations were conducted during the fieldwork as part of the case study approach, which ‘is a very effective tool for identifying dominant socio-cultural discourses’ (Gallant, Reference Gallant2008: 244). By undertaking an observer-as-passive-participant role category, observations were recorded to understand the context for interviews (Angrosino, Reference Angrosino2007). Information gained through this approach created an understanding of the specific circumstances in which the actors were operating (e.g., fly in-out to and from work locations, activities in the mining operations, and different settings between urban and rural areas). This assisted data analysis given the unique opportunity to have first-hand interaction with actors in their everyday lives, which leads to a better understanding of their beliefs, motivations, and behaviors (Gallant, Reference Gallant2008).

To support this approach, we used semi-structured, open-ended interview questions (Patton, Reference Patton1990) to start a conversation with the interviewees. Predetermined questions (see Appendix I) were developed but the order was modified based upon the interviewer's perception of what was most appropriate, allowing respondents to use their own words when responding. The interview questions were developed based on a thorough review of the literature on talent management strategies, as well as being piloted with executives from two different corporations who were not involved in this study. Rather than asking questions directly about the four frames (talent scarcity, diversity, community relations, and humanism), more generic questions (still related to the frames) were posed to investigate if the frames emerged naturally in conversation on relevant topics. The interviewer could therefore ‘follow the flow of conversation, asking questions as they occur naturally, and following-up with unanticipated questions when interviewees raise topics of particular interest or importance’ (Green et al., Reference Green, Duan, Gibbons, Hoagwood, Palinkas and Wisdom2015: 510).

The open-ended questions encouraged interviewees to move the conversations into their areas of interest (Gallant, Reference Gallant2008). For instance, in cases when a participant answered ‘high’ to the question related to the employee turnover rate in the organization, the interviewer then asked, ‘why is it high?’, leading to a more in-depth answer. In other cases, the participant naturally continued with the topics in the question reflecting interest or concern related to situations in which the work place or communities were positively or negatively affected.

These cultural or institutional ‘situations’ revealed the interviewees' frames. Ethnographic observation data in the form of notes assisted the researcher to interpret patterns of values, behaviors, beliefs, and social and business language (Creswell & Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2018: 90). In addition, company documentation (annual reports) and web sources (information about the mining operations and annual executive reports) were consulted as background information to understand the overall organization and business structures and culture. These sources also supported the analysis of the initial three translator actor levels identified: executives (headquarters), middle managers (regional head offices), and line managers (local operations).

We selected a single case study for illustrative purposes as this method enabled us to gain an in-depth understanding of translation at multiple levels of one organization and of the real-life complexities encountered by the MNE (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014; Yin, Reference Yin2009). While a single MNE was chosen from a single industry to decrease non-essential variance (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014), there was variation between the three subsidiaries across the three countries based on a range of variables at corporate and subsidiary levels, including organization size, and having both urban and rural locations.

Setting[Footnote 1]

The case study is of an independent commodity business unit of a large mining MNE (referred to as ABC), deemed appropriate due to its rapid expansion into Latin America while facing persistent talent shortages. The study of CTM in the mining industry elicits research challenges due to its fluctuating global demand, commodity prices, stakeholder expectations, and the need to maximize productivity and profitability (Wadsley & Hansen, Reference Wadsley and Hansen2016). This is heightened by an acute shortage of skilled labor, particularly in emerging economies (Nyamubarwa, Mupani, & Chiduuro, Reference Nyamubarwa, Mupani and Chiduuro2013). This situation is set against the production-oriented nature of this industry, which involves a vast workforce to maximize returns (Matangi, Reference Matangi2006), mainly located in rural operations.

Within the business unit studied here, ABC employed approximately 30,000 individuals across eight countries (Australia, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Canada, the US, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea), five of which were located in emerging economies. Headquartered in Australia, ABC had risen in an annual global ranking of mined commodity producers from tenth to fourth. Web sources on the company stated that this success was due to shareholder requirements, a globally-focused management team, demand for key talent at international business levels, and other pressures which led the company to seek superior performance when this business unit was established. Requirements from shareholders were implemented in a ‘Sustainable Development Framework’ (established at the holding-HQs level in Europe), including corporate citizenship strategies such as maintaining community relations to sustain and promote human rights, and respect cultural considerations and heritage. Hence, ABC had a CTM initiative developed at corporate level and diffused across all operations.

The emphasis of this study is on the operations in the emerging economies of Latin America where ABC had its largest investments and concerns about finding key talent to develop future projects after its recent investments of more than US$6 billion. The latest investment was expected to generate 6,600 direct jobs during construction and 2,450 permanent jobs once operating. ABC had ten operations across Peru, Chile, and Argentina, with an estimated need of 14,084 workers to develop all projects in the three countries. The Latin American head office was co-located in both Chile and Australia. Headquarter executives instructed ABC to attain high performance and profitability; ABC was required to translate and implement CTM strategies at all levels of the organization, with particular attention to the talent management project.

Sample

Results reported here are drawn from interviews with employees and direct ethnographic observation during the fieldwork where mining operations were located. The sample included interviewees from three managerial levels: executives as the strategy-makers, middle level managers as the translators, and first-line managers and professionals as the recipients. The sample was selected jointly through the VP of HR and the first author (lead researcher) within given constraints such as the availability of staff and sampling of different organizational levels and areas. Interviewees were aged 25 to 66, with a wide range of tenure from less than one year to over 25 years (with a mean tenure of 7 years).

Participants were asked for permission to record the interviews; however only ten agreed. The interviewer therefore took detailed notes of all conversations, and as part of the ethnographic observation, notes were also made on the ‘participant's view through closely edited quotations’ (Creswell & Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2018: 92). A total of 76 interviews were conducted in four mining operations; two in Peru, one in Chile, and one in Argentina. Three of these operations were in the Andes Mountains at elevations between 2,600 and 4,650 meters and about eight hours travel from the closest town. The fourth mining operation was 1,500 meters above sea level and two hours from a city. Thirteen interviews were held at HQ level; one in Australia (CEO), eight in the Latin America-HQ in Santiago, Chile, and four at the Peruvian principal office in Lima. Interviews were all conducted on site, with each lasting approximately 40 to 60 minutes. Interviews were conducted in Spanish except for two English-speaking executives who also spoke Spanish. Within the three managerial groups, employees were categorized into the three levels based on their position in the firm and their location (see Table 1).

Table 1. Interviewee managerial levels and sites

The participants from the three groups were diverse, providing comprehensive coverage of the phenomenon (Jansen, Reference Jansen2010). Thus, upon completing the 76 interviews, saturation was deemed to have been achieved. Building on the need for context-specific or indigenous research that involved the highest level of contextualization when focusing on emerging economies (Beamond et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016; Tsui, Reference Tsui2004), the primary researcher was a native Latin American whose first language is Spanish, fluent in English, and who had a nuanced understanding of the cultural, social, and business environments of the three countries involved (DeWalt & DeWalt, Reference DeWalt and DeWalt2010).

Data Analysis

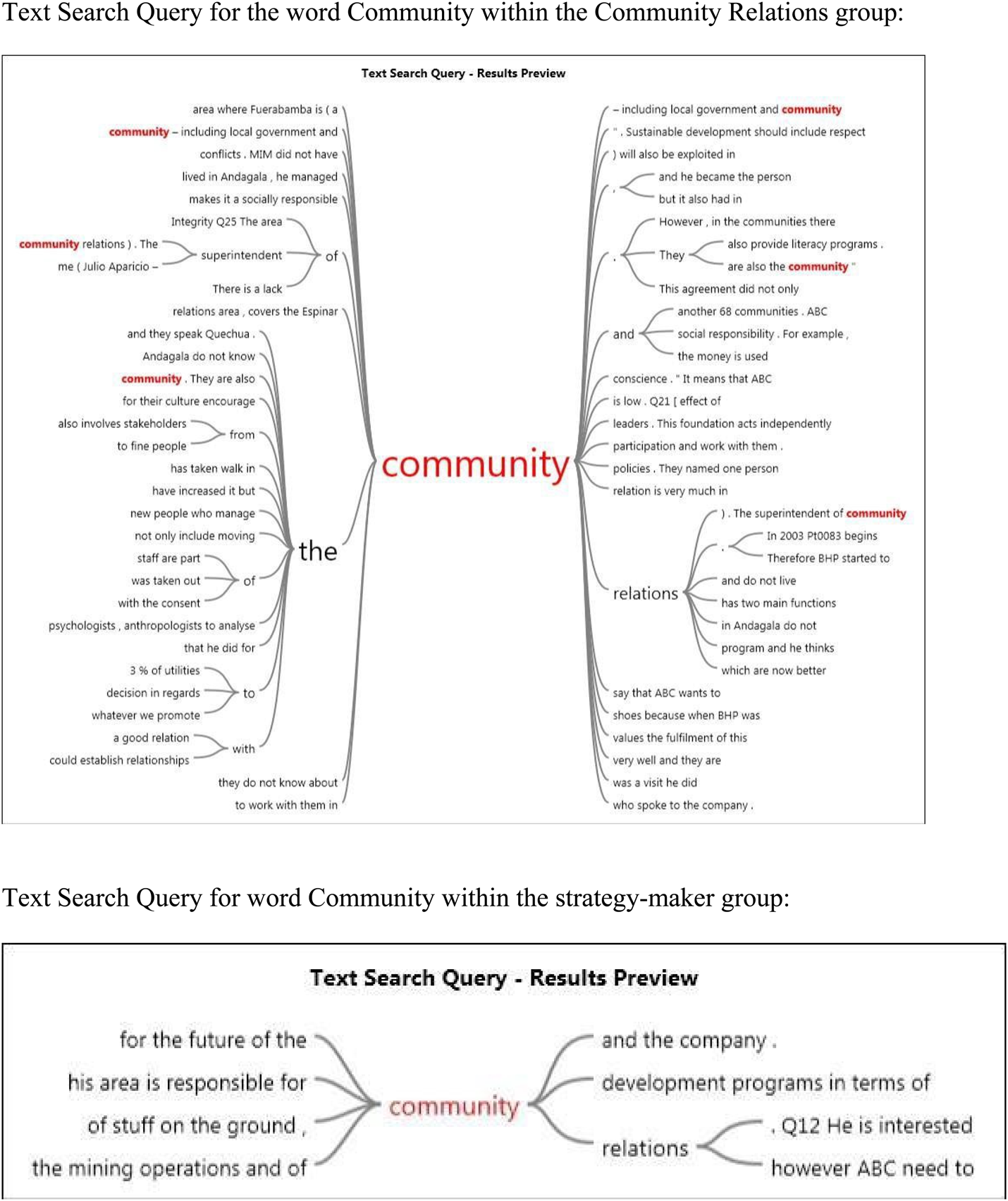

The detailed interview notes were translated from Spanish to English. To ensure that original meanings were preserved during translation, one person initially translated the interview questions from English to Spanish and another person translated the interview notes later from Spanish to English. The lead researcher made slight corrections to inconsistencies as necessary (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Lonner and Berry1986). The data was analyzed with the aid of NVivo software using two-cycle coding. The first cycle coding incorporated structured coding (Angrosino, Reference Angrosino2007; Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009) into categories related to the frames (skill scarcity, diversity, community relations, humanism). This involved identifying conceptual phrases that represented a particular aspect of each frame (for example skill shortages and stemmed words) and applying these codes to categorized data. These coded segments were collated for more detailed coding and further analysis of each frame. This first analysis aimed to develop a coding frequency report to identify themes, ideas, or domains consistent across the sample (Namey, Guest, Thairu, & Johnson, Reference Namey, Guest, Thairu, Johnson, Guest and MacQueen2008). After the structural coding, we refined the categories of each frame and developed further themes.

Analytic memo writing based on the ethnographic observations was used to develop the analysis further, encouraging reflection on the categories or frames and how they compared with knowledge derived from the literature (Angrosino, Reference Angrosino2007; Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009). For example, during the data collection period in one of the mining operations, a participant passed away providing the opportunity to observe his influence in ABC, the mining operation and the community (Gallant, Reference Gallant2008). Other examples include observing diversity differences between hiring indigenous and non-indigenous workforces in rural locations; as well as the value legacies of former MNE-owners.

The second cycle coding included a focused coding method performing deeper analysis of the categories found in the first cycle, discovering more words and phrases for the original codes (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009). Some of these were merged while others were used to create independent categories, such as additional frames and classifications (see Appendix II for examples of NVivo first and second cycle coding). Nodes and sets were then created, and text and word frequency queries run to identify the most frequently occurring words and concepts and compare them between the managerial groups (strategy-makers, translators, and recipients). Together with the observation data, this process allowed the researchers to determine relationships among characteristics of patterns and variables and to explain the diversity of the phenomenon by contextual determinants (Jansen, Reference Jansen2010).

RESULTS

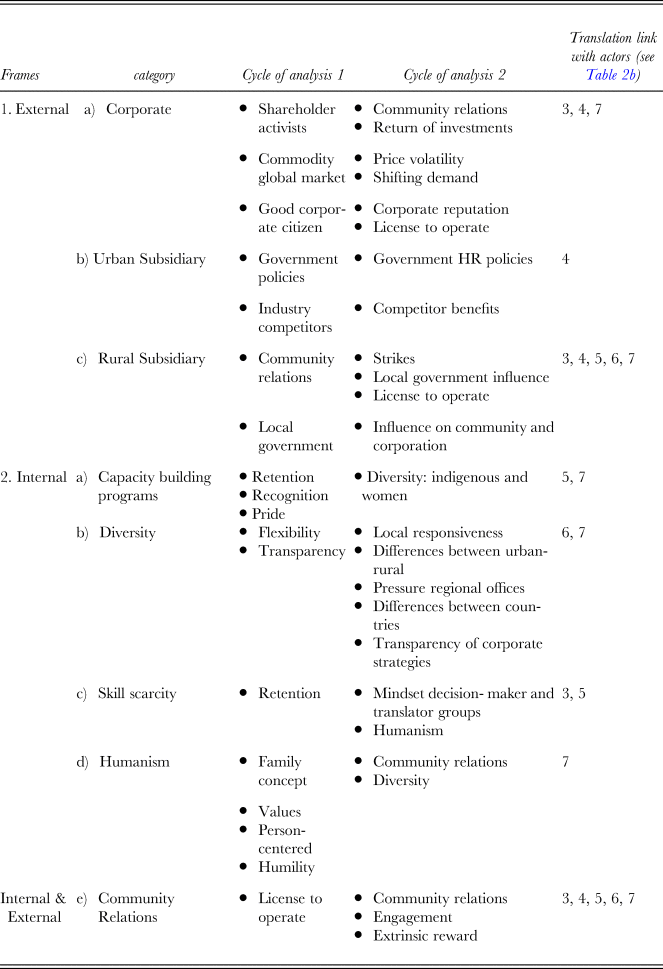

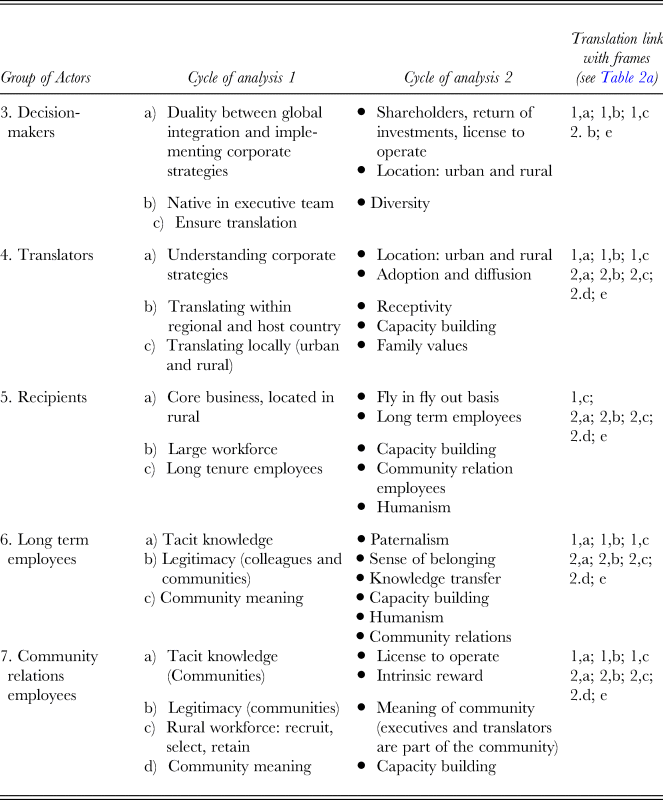

Based on this analysis procedure, the findings are presented focusing first on the different frames, then on the key actors, and finally integrating which frames were most relevant to which actors. The findings are summarized in Figure 2, and Tables 2a, and 2b.

Table 2a. Effect of frames on group of actors for the act of translating CTM strategies

Table 2b. Effect of frames on group of actors for the act of translation CTM strategies

Frames in CTM Strategy Translation

This section focuses on the relevance of the frames identified from the literature (diversity, skill scarcity, community relations, and humanism) in the context of CTM strategy translation into three Latin American countries, as well as suggesting new relevant frames that emerged from the interview data.

The first distinction that transpired as part of the first coding cycle was that factors affecting translation were being perceived as either external or internal to the organization (see Figure 2). The external frame focuses on factors from global and local context impacting the organization and is strongly related to the internal community relations and diversity frames. The internal frame includes those previously identified: skill scarcity, diversity, and humanism; and reveals a new category: capacity building. Although internal frames are distinct, the second cycle of analysis revealed that in some cases they overlap as one influenced another (see Table 2a, 2nd cycle of analysis column). The most relevant case is the ‘community relations’ category, which is relevant to both frames.

External frames

Within the external context, frames were divided into three categories: corporate, urban subsidiary, and rural subsidiary. Within the corporate category, three important themes emerged. The first is linked to demands from ABC shareholder activists regarding the relationship between investment returns and community relations, while the second relates to volatility of commodity prices and shifting demand. Both themes are connected to the third theme, the importance of ABC being a good corporate citizen and assisting local communities to boost the corporate reputation. All these external influences were managed by executives in Chile, Santiago, where the HQs of the Latin American region was located. Also, executives were not only focused on gaining high return on investment but also addressing community relations needs:

‘Shareholders asked the mining operations to improve the health and security of employees. The demands of the shareholders grew quickly, and they also demanded that the mining operations respected the communities. This leads the human resources department to generate plans’ (Manager HR).

Within the urban subsidiary category, the themes affecting talent management related to government policies and industry competitors. For example, during the mining boom, local governments implemented policies to increase salaries for locals and the competition for talent was fierce: ‘The government is considering a law to be approved where wages can be paid more than 18 times per year, and possibly the utilities will also be shared with the contractors’ (Superintendent). In addition, mining firms were combatting talent scarcity in the market by increasing reward packages: ‘people are leaving more because they are being offered more money or because they are offered other benefits’ (Supervisor). Most of the ‘other benefits’ from competitors were extended to employees’ families such as health coverage. Interestingly, most of the key executive talent operating in the region were trained in Argentina (at the rural and urban subsidiaries).

In the rural subsidiary category, the community relations frame was evident, and demands from shareholders were emphasized more in Peru due to the strong influence of communities and indigenous populations. For example, local governments could influence community relations by encouraging local communities to participate in regional business, while anti-mining sentiment and environmentalists carried on protests that could delay or halt projects, affecting productivity and business sustainability: ‘The local government used to fine people from the community who spoke to the company’ (Supervisor); ‘There are confrontations with anti-mining groups, and resentment from the communities and strikes from other towns’ (Manager). Also, to employ people from rural settings: ‘The government demands that companies [MNEs] employ people from the region [rural areas]’; ‘my role is to be in charge…of the external competence of ABC’ (Superintendent).

ABC's community relations section, which includes program development, reported directly to the general manager of each mining operation. Although staff had a high level of commitment to the communities, community relations could still be one of the most persistent issues faced. For example, Peruvian indigenous and community populations (comuneros) frequently organized protests over environmental protection, water access, economic development, jobs, and land access rights and, in some cases, stopped operations. As a social power, comuneros were a considerable factor for building community relations and obtaining the social license to operate in Latin America: ‘Social license and coexistence mean social peace’ (Superintendent); ‘The mission of his area is to obtain the social license to operate. This would mean an avoidance of conflicts, identification of capacity building programs coordinated with the development of programs, the development of communication strategies and […] sustainable projects’ (Superintendent).

Internal frames

Focusing on the internal organizational context, we found the expected frames (diversity, skill scarcity, humanism, community relations) as well as a noteworthy new frame: capacity building programs, which generate retention, recognition, and a sense of pride for the organization. We also noted the importance of community relations within both internal and external frames. The capacity building programs were associated with many of the other identified frames, for example, diversity was focused mainly on the importance of capacity building for indigenous populations, providing more opportunities for women, and valuing long-term employees’ tacit knowledge: ‘Capacity building programs for corporate social responsibility are fundamental for local development and to reach sustainability in the region’ (Superintendent); ‘they [HR department] have them [women] working in admin and this areas, but they are engineers and have studied for 4 or 5 years. They do not allow them to reach their potential’ (Superintendent); ‘[mining operation name] has a good percentage of older people who would be ready to retire soon but they [management] do not have a strategy to address this problem’ (Superintendent). At country level, the effect of capacity building programs in the three countries was similar.

Exploring the diversity frame, two themes emerged: flexibility and transparency. Local responsiveness frequently required changes to CTM strategies and this generated pressure on regional offices and business units: ‘We [corporate HR] give general guidelines, but each local [HR department] has some flexibility to apply them’ (Corporate HR Manager); ‘The salary policies come from Australia, but they should not implement the same politics from Australia in [the mining operation] due to our differences’ (Superintendent); ‘When hiring locals, regional ancestral activities must be considered. For example, […] stones have a special meaning that integrates the cosmos with nature […] these ancestral customs lead to a different communication manner between the locals […] and those who aren't locals’ (Superintendent).

Some nuanced differences with regard to diversity emerged at country level. For example, the involvement of indigenous populations in the workforce is more prevalent in Peru than in Chile or Argentina. Gender differences in rural locations also differ between countries: the Peruvian and Chilean workforces were male-dominated, while Argentina had a group of technically-skilled women driving large trucks, yet no women held managerial positions in Argentina, but a few did in Chile (one at corporate level) and Peru (in rural subsidiaries).

Openness and transparency of CTM strategies within the diversity frame was also important for translation. For example, while some executives described a particular CTM program with enthusiasm, employees mostly from rural settings indicated disappointment with the same program: ‘As [ABC] is a young innovative company with good values, it attracts talent….we realize that the internal talent is [the corporate program]’ (Vice-president); ‘It is an important program from Australia that does not work here’ (Superintendent HR). CTM programs were also relevant for communities where businesses operated; however, they were not adapted to rural needs.

Frames around skill scarcity were found to differ in each country. For example, while operations in Peru and Chile, with medium to high levels of skill scarcity, were worried about the number of people needed to sustain the business, in other operations, such as in Argentina, shortages were low. In the former countries, their main issue was about obtaining the best talent within a competitive labor market. In Argentina, the main issue was the lack of professional growth opportunities, as the country had few industry competitors, resulting in a low level of turnover and a feeling of monotony.

Within operations, retention programs were linked with humanistic structures, such as families being considered within local talent management strategies. This frame was found to be similar in all three countries. Additionally, it was considered important to recognize the values and person-centered aspects of employees and the importance of their families and communities. Employees who felt they were recognized indicated they felt proud of the organization:

‘The [corporate leadership program] is formed by the corporate executives of [ABC] but they do not have any humanity. This theory needs more Latin soul…Executives need to show a little bit more about whom they are inside and take off the “ranks” jacket […]. When the executives take off the “ranks” jacket and show their sensitive side, then communication becomes clearer and the managing of the business becomes clearer too. They should help make the person feel more like a person rather than just a worker. This is what having a soul means’ (Superintendent).

For example, where the CEO had visited mining operations and the communities where they are located and had informal conversations with workforces, increasing employee retention.

This section evidences that the community relations category is particularly important in all three countries. However, this frame is predominant in Peru due to the high number of indigenous populations involved in rural operations. This category is embedded in the internal and external frames, as well as across the groups of actors (as highlighted in this section and Table 2a, and 2b) and is considered as a key frame to achieving social license to operate.

Who is Involved in Translation?

Building on the generic structure of actors in translation including strategy makers (headquarters), translators (regional head offices), and recipients (local operations), we describe here the configuration specific to ABC.

Corporate executives (strategy makers) from ABC's HQs (the CEO, vice presidents, and general managers) are in a position of duality between global integration (factors reflected in the external frame: requests from shareholders, commodity markets, and being a good corporate citizen) and the implementation of corporate strategies (factors reflected in the internal frame). In addition to those located in the HQs, we also found vice-presidents located in regional head offices in urban locations, and general managers who were situated in subsidiaries at both urban and rural sites. These included an expatriate from Australia in Argentina and a local-indigenous manager in Peru, both located in mining operations.

The translators group largely involved decision-makers (middle managers) spread across regional head offices and local mining operations including communities around operations. They had the task of translating corporate strategy into the region's businesses as well as into the host country context. These actors appeared to have the most complex role of balancing corporate strategy and local institutional and cultural factors, particularly those in rural- community areas. For example, when this group of actors was requested to implement corporate strategies from the HQs level and to adapt them locally, subsidiary and rural operations sometimes rejected them based on humanism principles: ‘They [corporate] need to make the human resources department more humanized. When they transmit corporate polices and business strategies they need to take into consideration the different intellectual levels …that may be present in the subsidiaries…’ (Supervisor – rural operations).

The recipient group included superintendents, supervisors, and workforces mainly located in rural operations, but some were also based at the regional head offices. The core business of the MNE occurred in the rural operations, which included employees with long tenure who had built a stock of tacit knowledge and developed strong relationships within the operation and community contexts. Approximately 85% of the employees were located in regional business offices or rural operations in Peru, Chile, and Argentina; in addition to the managerial levels, most operators were employed on a fly-in fly-out basis.

In addition to these actors, we also identified two additional groups of actors who played significant roles in the translation process, but who cut across the executive middle manager/ line manager distinction. The first subgroup was employees who had been working in the business for several years, referred to as long-term employees (LTEs). The second sub-group was employees who had been working closely with communities, mainly involved in CSR activities, that we call community relations employees (CREs).

LTEs are staff who had been working in the mining operations for a long time and had experienced working for the same mining operation under different ownership. LTEs are senior personnel who, through their tacit knowledge gained during years of experience and strong relationships with peers and communities, have gained legitimacy and can build strong community relations: ‘The well-organized structure of [the mining operation] and its success, at the internal and external levels, are thanks to the fact that long tenure employees have maintained those good values and have passed them on’ (Supervisor); ‘As a result, [the mining operation]’s culture is highly embedded in our values…these values have also been extended to the comuneros’ (Supervisor, Community Relations). For example, during the fieldwork, one of the LTE-middle managers from a large mining operation in Peru had a sudden accident and passed away. This caused a tremendous shock in the overall operations, which stopped about 70 per cent of work production and affected surrounding communities. The mining operation felt empty and staff were waiting for a corporate announcement, expecting a paternalistic response.

An LTE interviewee from one mining operation noted the values learned from previous owners of the operation and the translation of these values to other employees and the community: ‘This organizational culture [from the second ownership] taught employees to have values such as not to lie or swindle, and to have honor and integrity’ (Supervisor). The interviewee also advised that this culture was also extended to communities, strengthening community relations. Most LTEs were either line or middle managers, but a few were executives, including the CEO and a general manager of a mining operation. LTEs had a deep sense of belonging to the mining operation, or ‘wearing the shirt’ as they call it and were hence in a strong position to build community relations: ‘Almost all of them have been there since the start of this operation and they wear the shirt of [the mining operation]’ (Manager – RIP); ‘The general manager of [the mining operation] is a native from the region and speaks both languages [Spanish and Quechua]’ (Manager – RIP).

The second sub-group, CREs, includes largely superintendents who worked closely with communities; they gained trust within the communities and were responsible for obtaining the social license to operate. They had particularly strong link to the comuneros: ‘Additionally, it [community relations] helps human resources to develop recruitment systems and personnel selection. Their knowledge of the condition and idiosyncrasies of the region helps to develop programs to retain local talent’ (Superintendent – HR); ‘In this area, 60% of the employees come from the communities or comuneros’ (Superintendent – operations).

Both LTEs and CREs were intrinsically motivated by their linkages with communities, their area of work and the mining operation, and were frustrated when others could not see the importance of this: ‘There is a lack of community conscience. ABC [corporate] lacks conscience about the fact that staff are part of the community. They are also the community’ (Superintendent); ‘Even when I'm motivated by my work because I like it, at the company level I feel undervalued…. my motivation is high due to conviction and the passion for my work’ (Superintendent).

Country Level Variance

Differences and similarities were found between the three countries (see Table 3). Within the external frames, Chile is the regional HQ for the ABC operations in Latin America, exercising great influence on the other country-operations. However, because the biggest operations and community conflicts were in Peru, a large concentration of regional HQs decision-making activities were focused on these operations. Hence, while Chile acted as a mediator between executives and regional operations, most of the external frames were predominantly relevant in Peru, affecting the act of translation from corporate. Argentina's operations did not have any major influence on the translation process. This country acted as talent support, as key managerial talent was trained to be transferred to other operations in the region.

Table 3. Differences and similarities between the three countries

Within the internal frames, capacity building, humanism, and community relations were relevant in all three countries. However, the latter had more influence in Peru based on the large number of indigenous populations involved in rural operations. Argentina and Chile paid more attention to gender diversity, the former involving managerial positions and the latter in labor; and Peru and Chile present the highest level of skill shortages in the region. In relation to the groups of actors (executives, translators, recipients, LTEs, and CREs), all of them were active in all three countries. However, while most translators were either in regional head offices and rural sites, the recipient, LTEs, and CREs groups were mainly located in the rural areas in all three countries.

How Actors Adopt Local Frames in the Translation Process

Here we focus on how and why the translation process happens, including obstacles found during the act of translation, given the various frames and actors involved across the different countries. During the act of translation, the perspective of actors on frames varied (see Figure 2). For example, the focus of the strategy-making group was to achieve a good reputation, a social license to operate, and the sustainability of the business, as part of global integration and localization. The focus of the translator group was to understand urban-rural institutional and cultural differences, while the LTE and CRE groups were focused on the community relations and the recipient group primarily on internal frames. Although internal frames were important to the translator, LTE and CRE groups too, all five groups of actors (including strategy-makers, translators, recipients, LTEs, and CREs expressed a profound interest in the external-rural subsidiary and internal-community relations frames.

Some frames differed among the actor groups due to their work context, for example skill scarcity: ‘There is no skill shortage’ (Corporate General Manager HR) versus ‘The corporate area of ABC has unrealistic expectations because they were told there is not a high turnover rate, when in fact there is’ (Superintendent) versus ‘At the corporate level…. I cannot see any strategies to help fix the turnover rate, skill shortages, and the amount of professionals needed in the future’ (Superintendent) versus ‘Another option is to steal people from another company’ (Executive Vice-President). The mindset of the first actor was on skill shortage in the region compared to other country-operations with substantial shortage challenges. The second and third actors’ views on this frame were from the perspective of their mining operation and their need to obtain key talent, while the last actor's view was referring to his own business area (engineering-construction). These corporate, urban and rural differences caused stress within the translator and recipient groups.

The strategy-makers group developed generic corporate talent management strategies based on shareholder requirements. Strategies included corporate citizenship activities such as maintaining community relations plans to sustain and promote human rights and respect cultural considerations and heritage, as well as effects from the global commodity market. Executives also had the important task of ensuring that the translator group translated these strategies to other organizational levels and fit them to local institutional and cultural frames affecting the availability of talent:

‘Basically, what we have here [the Vice President of HR] is the human resources strategy for the entire unit, or the global strategy of HR for all ABC. And they [HR heads responsible in each country] in turn have to elaborate their own strategy in line with ours and in line with punctual needs that each business has. Besides [HR strategies having to be in line with] each country also, from the administrative point of view, taxes are different, the need to meet each country's labor legislation requirements. It is not the same in Peru as in Chile as in Australia, Canada, etc. But basically, guidelines are being managed from here’ (Vice President of HR).

The effects of globalization cause strategy-makers to drastically change corporate strategies interrupting the translation process. For example, within the external context at the corporate level, commodity price volatility required adjustment of strategies. During the mining boom, business strategies were focused on expansion and the need for more talent in a tight labor market, particularly in Peru due to large investments at the time. As one of the VPs acknowledged: ‘In the future they [the HR department]…will need 3,000 more people…the [company] will finish [its operations] in 2012, and its expansion will last until 2023’. Moreover, shareholder activism imposed demands on corporate strategies to be a good corporate citizen and develop strong community relations: ‘demands of shareholders grew quickly and they also demanded that the mining operations respect communities…improve health and security of employees’ (HR manager).

Most actors in the translator group managed professionals and thousands of workers predominantly in rural mining locations, revealing different effects on external and internal (see Table 2a, 2b). The ability of the translator group to recognize corporate (global) and local (urban and rural subsidiary) business mindsets and appreciate institutional and cultural values reflected in the internal and external frames, impacted on the act of communication and translation. For example, local government policies and community demands are external frames affecting the translation process, such as when the government requested subsidiaries to employ people from rural areas; or when local governments did not provide sufficient infrastructure for communities: ‘the lack of government presence results in…demanding things of [ABC]’ (Manager).

Translators also ensure that the recipients perceive the strategies as corporate intended. However, on many occasions, recipients perceived corporate strategies as foreign, and not having been translated into the local context. The presence of executives in the urban or rural settings assisted in enhancing the translation process, however, one substantial problem with this process was the way in which actors communicated strategies. For instance, in the case of ABC, a particular corporate talent pool strategy was perceived as foreign or non-existent by some of the translators and recipients, adding to the problem of talent scarcity: ‘There is only a perception of who may form part of the talent pool, it would be important …[if this] were more transparent and this could form part of retention programs for personnel’ (Supervisor).

In an other case, an expatriate strategy-maker noted his concern with the lack of reception from line managers and the workforce to perceive a corporate health and safety strategy, due to the direct way the strategy was being delivered. As a paternalistic society, Latin American countries expected a different approach to the introduction of corporate strategies. LTE and CRE groups appeared more likely to be able to communicate strategies in a way that recipients (within their work contexts and communities) were more receptive towards new strategies because of their embeddedness within the work context, their passion for their work and their humanism: ‘The company is like my son, I have known it since it was born’ (Supervisor).

Business location also influences the way translation and reception may occur. For example, workers are more highly educated in urban subsidiaries compared to rural locations, which facilitates the act of translation. Nevertheless, translation does not always reach all recipients, or becomes lost due to the large number of people working in a mining operation, and the distance from urban business. For instance, when responding to the question on alignment between talent management strategies and the overall business strategy of ABC, a participant stated, ‘No. I don't think there is any …’ (Superintendent). However, employing native actors may influence the translation process. Referring to the presence of a native general manager of a mining operation, a participant explained how this helped to build community relations: ‘… a very big advantage which helps to fix a lot of the problems […] in the communities’ (Manager-RIP).

In the rural context, for a better flow of communication to recipients, translators need to develop different ways to transmit corporate strategies that fit the diverse recipient actors (professional and non-professional) by adopting more humanism: ‘They [executives] need to sensitize the communication of corporate strategies, especially when they arrive to the mining operation. They must avoid sending messages that are received in a cold manner’ (Manager).

The lack of local industry competitors also affects the translation of strategies. As aforementioned, the translator and recipient groups mainly experienced an absence of career advancement due to the lack of industry competitors in Argentina, while in Peru and Chile the experience was different. As a result, the sense of demotivation negatively affected the reception of corporate strategies in Argentina. The LTEs and CREs were clearly able to use their local knowledge and legitimacy to leverage their skills and low-level power (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008) to translate (and receive) corporate strategies in rural locations, not only at an internal operational level, but also in a way that helped to build community relations: ‘I have molded to the culture here and there has been no culture clash. People know me and respect me’ (Superintendent of community relations). Their importance was, however, not valued by strategy-maker and translator actors, yet, these two groups of actors were crucial to the translation process, and to gaining the social license to operate.

In conclusion, the frames being applied and the different actors involved in the translation process are depicted in Figure 3. Strategies move from strategy-makers to translators who experience an enormous responsibility to understand corporate, institutional and cultural structures embedded in urban and rural settings, as well as the way receiving societies perceive corporate's strategies. Figure 3 demonstrates differences in how ideas affect corporate and subsidiary (urban and rural) locations.

Figure 3. Translation process of corporate talent management strategies across subsidiaries in emerging economies

The subsidiary level experiences the effect of the different frames that move from urban-rural and vice versa, generating a vast flow of (internal and external, urban and rural) frames. Hence, when corporate strategies reached subsidiaries, especially at the rural level, these strategies in many cases were lost in translation, such as the corporate talent management strategy case. As aforementioned, this strategy was perceived as non-existent at the rural context. LTE and CRE groups would play a key role in the act of translation if they had themselves first been recipients and had valued the corporate strategies.

A significant finding that plays a crucial role in the process of translation is discovering community relations as a powerful frame (see Table 2). As an HR Superintendent and a Personnel Manager stated: ‘community relations… represents… the corporate image of ABC….it handles the relations with the local government’; ‘diversity … are initiatives and they are not just for capacity building but also for any other necessity that arises….it is managed through the community relations area…they create foundations to improve the productivity of the region [rural areas]’. This frame serves as a mediator between internal and external frames, and shareholder and community demands. Effects of this frame may result in obtaining (or not) the license to operate and enhancing (or not) reputation, important to the sustainability of the business.

DISCUSSION

This study explores the interaction between frames and actors in the translation of CTM strategies of an Australian MNE into its Latin American subsidiaries. Specifically, we have explored the extent to which contextual frames affect organizational actors when translating corporate strategies to subsidiaries in this region of the globe. By drawing from both the translation and talent management literatures, an empirical case study has demonstrated how actors (in different countries and at different urban and rural sites within countries) understand CTM-related frames relative to corporate intention (globalization) and local acceptance (localization). The case study supports existing literature regarding important Latin American frames and actors in the translation process, as well as identifying new frames and actors important to this process. Findings provide important managerial insights and imperatives for firms to enhance their businesses in Latin America.

Theoretical Implications

The study contributes to the emerging stream of literature on talent management and applied in the Latin American context (Bae & Lawler, Reference Bae and Lawler2000; Beamond et al., Reference Beamond, Farndale and Härtel2016; Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2012a, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b; Farndale et al., Reference Farndale, Scullion and Sparrow2010; Meyers & Van Woerkom, Reference Meyers and Van Woerkom2014; Newburry et al., Reference Newburry, Gardberg and Sanchez2014). By incorporating insights from the translation literature, it was possible to uncover the flow of CTM strategy from corporate to subsidiary, evolving as it moves from location to location and between actor groups (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2009; Czarniawska & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005). Support was found for the presence of multiple contextual frames (external and internal) that affect the translation process (Czarniawska-Joerges, Reference Czarniawska- Joerges2004; Rettie, Reference Rettie2004). The external corporate priorities (e.g., commodity markets, shareholders, and competition) have a strong linkage with the internal context (e.g., capacity building, community relations, talent scarcity and building humanism into management).

By adopting a more nuanced perspective on the different frames, this provides greater insight into the actual process of translation. For example, most translation and talent management research has been focused on large organizations operating in developed urban areas. However, as aforementioned, subsidiaries operating in urban and rural locations may face differences including worker ethnicity, skills and ways to traveling to work (fly in-out), (Jara et al., Reference Jara, Perez and Villalobos2010). While acquiring and developing talent in an urban location, it likely easier to find highly educated talent, whereas recruitment efforts in rural locations need to focus more on building relationships with communities and training local people. This can affect labor productivity positively or negatively (Jara et al., Reference Jara, Perez and Villalobos2010). Hence, when CTM strategies move from urban locations to rural, strategy-makers and particularly translators face different challenges during the diffusion process, leading to a divergent outcome (Czarniawska & Sevón, Reference Czarniawska and Sevón2005).

There is also evidence that the external and internal frames are interrelated. For example, the capacity building frame was found to generate retention, recognition, and a sense of pride for the organization. Other studies support this finding, whereby capacity building is linked to corporate reputation, which in turn, generates pride in the organization and greater receptivity of corporate strategies (Tymon et al., Reference Tymon, Stumpf and Doh2010). Developing capacity building programs was, however, also found to be closely related to building community relations, particularly among indigenous groups and women, as well as acting as a mechanism to cope with skill scarcity, acceptance of diversity and an understanding of humanism.

In Latin America, the findings demonstrated that the community relations frame and the translator group are key aspects to the act of translation. It is perhaps unsurprising that community relations are highly important as corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in developing nations have been found to be important due to low social economic development (Welford, Reference Welford2004). The translator group that interacts between corporate and local contexts, plays an important role to address the differences between the countries. The translator group socially constructs path dependency between corporate and local practices during the translation process (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2005, Reference Boxenbaum2006). The study showed that translators need to understand both external and internal frames, while having their own particular frames based on their personal background. At the same time, translators learn from the corporate culture to be able to translate strategies and ensure local receptivity, as well as communicating concerns about these strategies from local sites to HQs.

In addition to the importance of translators, the study identified two other actor groups with a critical role in the Latin American context: LTEs and CREs. These people are less categorized by organizational level and more by their length of service with the firm (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska-Joerges2014). The LTEs and CREs were clearly able to use their local knowledge and legitimacy to leverage their skills and low-level power (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Reference Bouquet and Birkinshaw2008) to translate (and receive) corporate strategies particularly in rural locations. LTEs and CREs most often talked about community relations and how corporate strategies fitted with the local context, including individual and family (direct families, close colleagues, and community) needs. The findings also suggested that the importance of LTEs and CREs was not recognized by strategy-makers and translators, despite the two group of actors being seemingly crucial to the translation process and to gaining the firm's social license to operate.

This research also offers further evidence of skill scarcity in these emerging economy contexts, where retention is a key element to business success in these markets (Vaiman et al., Reference Vaiman, Scullion and Collings2012). However, within the skill scarcity frame, this study found two barriers to the act of translation: misconception of ideas by actors from different groups (i.e., some clearly seeing a skill shortage while others did not), and the activity of local competitors (or the lack thereof in Argentina) caused turnover of high skilled employees. Similarly, we found agreement about the need for more humanism within CTM strategies, a characteristic of collectivistic cultures where social and psychological contracts are centered on the person as part of the community (Elvira & Davila, Reference Elvira and Davila2005a). Hence, the acknowledgement of humanism within corporate strategies enhance translation of corporate strategies from top-down and enhances adoption and diffusion of organizational practices (Kostova & Roth, Reference Kostova and Roth2002).

The community relations frame was expected to be linked to shareholder activism (Porter & Kramer, Reference Porter and Kramer2006) and evidence was found to support this (see Table 2a). Shareholder activism imposes demands on being a good corporate citizen particularly in countries where the power of societies influence reputation (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Musila and Chowdhury2005), such as the case of Peru. In this study's organization, they requested that the strategy-maker group develop social strategies and increase health benefits and security for employees, which in turn made diffusion of corporate strategies easier for the translator group, and also generated greater reception by the recipient group. With greater community acceptance, the firm gained its social license to operate and hence built its corporate reputation.

Another externally-focused frame at corporate level was linked to commodity price volatility. At the time of data collection, the price of ABC's commodity was very high generating strong talent competition between subsidiaries from the same industry. However, after the mining boom, business growth slowed, share prices and profits fell, which influenced organizational strategies and led to sustainable cost reduction including talent management budgets (Deloitte, 2014). Along with the effects of government policies and competitors, these external factors were found to affect operations in urban and rural areas in different ways. Translators may face dissimilar local, provincial, and federal government policy issues when implementing corporate strategies, as well as having to cope with different sets of competitors for talent. For example, in Argentina rural governments play a role in regional economic development, and the power of provincial legislative branches varies substantially (Gibson & Suarez-Cao, Reference Gibson and Suarez-Cao2010). In Peru, the rapid expansion of large-scale mining activity has generated several protests and anti-mining groups, where rural inhabitants attempt to preserve their livelihood and environment (Taylor, Reference Taylor2011). In the study, the community relations section of ABC played a crucial role in mediating rural conflicts, which enhanced the translation process. Therefore, community relations became a bridge between external and internal frames, and a way to enhance translation of strategies at rural level.

Although corporate strategies may be translated to fit recipient-mindsets, the question remains how strategies are translated (to urban or rural contexts) without losing their initial corporate intent (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006). Findings from this study (Figure 2) reveal central aspects that impact the act of translation; how well local actors understand these aspects will influence how effective they are in implementing practices, generate productivity and sustainability of the business. As the study demonstrates, some of the most important aspects during the act of translation resonate with previous research: each actor group may have a different set of frames (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2012), e.g., global-corporate, local-urban, or local-rural; effects of globalization (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Bozkurt and Sparrow2012); ways of communicating to employees from different organizational levels (Davila & Elvira, Reference Davila and Elvira2012a, Reference Davila, Elvira, Brewster and Mayrhofer2012b); selection of the right talent actors (Meyers & Van Woerkom, Reference Meyers and Van Woerkom2014) in each group (particularly for the translator group); and motivation for intrinsic rewards (Thite et al., Reference Thite, Wilkinson and Shah2012). At the same time, local frames may be transformed (Boxenbaum, Reference Boxenbaum2006) as societies learn from corporate cultures (e.g., different ownership).

Practical Implications