Lurking behind a well-known fact—rapid urbanization has left huge populations living in informal areas—lies a startling truth: tens if not hundreds of millions of people live under some form of criminal governance. Who, what, and how criminal organizations govern all vary enormously. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, heavily armed drug syndicates provide everyday order, while police enter almost exclusively in lethal raids that send residents scrambling for cover (Arias and Barnes Reference Arias and Barnes2017). In São Paulo’s periphery, a hegemonic prison gang bans unauthorized homicides and resolves disputes via juries of imprisoned members, but maintains a light territorial presence; police enter at will but do not challenge the gang’s authority, and a peaceful, low-homicide “symbiosis” (Denyer Willis Reference Denyer Willis, Jones and Rodgers2009) obtains. In Medellín, Colombia, hundreds of neighborhood gangs enforce property rights, tax local businesses, provide high-interest loans, and even produce and sell food staples; in nearby Cali, gangs take little interest in governing civilians (Arias Reference Arias2017; Blattman et al. Reference Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobón2020). Even in the United States and the UK, criminal governance at the local level can be intense, if largely off the radar (Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2018; Jankowski Reference Jankowski1991).

What unites these cases is that, for those governed, states’ claims of a monopoly on the legitimate use of force ring hollow; for many quotidian issues, a local criminal organization is the relevant authority. Yet the state is far from absent: residents may pay taxes, vote, and call the police for problems beyond gangs’ purview—or even to inform on gangs as punishment for abusive behavior (e.g., Barnes Reference Barnes2018). States may actively contest criminal authority, but just as often they ignore, deny, or even collaborate with it. The results are distinctly non-Weberian: states and the criminal groups they are purportedly trying to eliminate form a “duopoly of violence” (Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997, 61), one that can be competitive or collusive (Arias Reference Arias2017; Barnes Reference Barnes2017), turbulent or stable.

This duopoly of violence distinguishes criminal governance from both state governance and common forms of non-state governance. In our workplaces, civic organizations, and even families we are subject to the rules, impositions, and decisions of those vested with authority. But in all these cases, as Weber (Reference Weber1946) pointed out, the state is the final enforcer and enabler of such authority. No such backstop underlies governance by non-state armed groups: their authority rests on their own coercive capacity, in at least nominal opposition to the state’s. In this, criminal governance resembles rebel governance. Yet rebels’ opposition is starker, and rebel governance—generally understood as part of a larger “competitive state-building” strategy (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006)—typically occurs in “liberated zones” of near-exclusive control (e.g., Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Weinstein Reference Weinstein2006). Criminal groups’ opposition is subtler; they rarely establish strong territorial control, confront state forces, or seek to supplant state governance entirely. Consequently, criminal governance often hides in plain sight. It can thrive in backwaters and bustling metropoles alike, persisting through economic booms and busts, its relationship to shifting rates of crime or violence largely unexplored.

Indeed, what most distinguishes criminal governance from both state and rebel governance is its embeddedness. It flourishes in pockets of state weakness that are nonetheless surrounded and intermittently penetrated by strong state power, like prisons and low-income neighborhoods. To lump criminal governance in with other forms of non-state governance elides its most intriguing characteristics: simultaneously born of, shaped by, in opposition to—but in subtle ways complementing—state power. “Born of” because legislating, and hence outlawing, is a primordial state function (Koivu Reference Koivu2018); states may fight crime, but they create “the criminal.” “Shaped by” because virtually all state actions, from policing to zoning, from infrastructure provision to welfare policy, have substantial effects on criminal groups’ incentives and capacity to provide governance. “In opposition but complementary to” because criminal governance, while it seeks to keep some parts of the state out, may allow others in. For example, after the Okaida prison gang conquered and pacified a violent favela neighborhood in João Pessoa, Brazil, it specifically prohibited crimes against state social-service providers so that they would feel safe enough to resume their visits, to residents’ great relief.Footnote 1

As this example suggests, the embeddedness of criminal governance can produce unexpected and paradoxical crime–state dynamics (e.g., Arias and Barnes Reference Arias and Barnes2017). State repression itself—especially mass incarceration and drug prohibition—can inadvertently furnish the human and financial resources criminal groups use to govern (Cruz Reference Cruz, Bruneau, Dammert and Skinner2011; Dias Reference Dias2009; Lessing Reference Lessing2017; Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). Conversely, criminal governance can lead to reduced state repression, in part by being useful to states. Recent scholarship has identified cooperative crime–state arrangements based on corruption, alliance against other armed threats, or outright crime–state integration (Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Koivu Reference Koivu2018; Snyder and Durán-Martínez Reference Snyder and Durán-Martínez2009). Criminal governance points to distinct, “symbiotic” relationships (Adorno and Dias Reference Adorno and Dias2016; Denyer Willis Reference Denyer Willis, Jones and Rodgers2009). Criminal organizations can bring order to spaces—especially urban peripheries and prison systems—that states perennially find difficult to govern. As these spaces expand, criminal governance may become increasingly important to social stability, and contribute, however perversely, to state-building itself.

Historically, state formation often depended crucially on collaboration with, and absorption of, criminal groups (e.g., Andreas Reference Andreas2013; Barkey Reference Barkey1994; Koivu Reference Koivu2018). In the modern era, and particularly in the context of a global war on drugs, the criminal domain has been cordoned off in important ways from the state. The same governments that openly seek out and strike peace deals with armed rebels systematically rule out negotiation with criminal groups—or even alternative policies that might reduce violence—as morally corrupt and politically toxic (e.g., Cruz and Durán-Martínez Reference Cruz and Durán-Martínez2016). Yet criminal governance persists. Given its prevalence in developing countries, and its presence even in wealthy ones, it is likely the most common form of oppositional non-state governance, affecting millions of citizens across political, social, and economic contexts.

Political science has yet to adequately grapple with this reality. Empirically, the extent and range of variation of criminal governance remain largely unmeasured. Analytically, cognate literatures on state formation and non-state governance offer some traction but also obscure key aspects of how and why gangs actually govern. To be sure, scholars have provided rich ethnographies of criminal governance (e.g., Blok Reference Blok1974; Feltran Reference Feltran2010; Jankowski Reference Jankowski1991; Zaluar Reference Zaluar2004); warned of its potentially disastrous effects on democratization, citizenship, and the rule of law (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2006; Córdova Reference Córdova2019; Leeds Reference Leeds1996; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993); explored its causes (e.g,. Barnes Reference Barnes2018; Duncan Reference Duncan2015; Ley, Mattiace, and Trejo Reference Ley, Mattiace and Trejo2019; Yashar Reference Yashar2018); and developed typologies (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Barnes Reference Barnes2017). Building on these contributions, this article develops a generalizable conceptual framework that delimits criminal governance, its key dimensions of variation, and its underlying logics.

I make four contributions. First, I define criminal governance and situate it with respect to corporate, state, and rebel governance. I argue for a broad definition that encompasses not only governance over non-criminal “civilians”Footnote 2 but also over both members and non-member criminal actors and markets. Second, I develop a set of dimensions centered around straightforward questions—the who, what, and how of criminal governance—drawing on extant research to illustrate ranges of variation. Most novel is a Weberian dimension, contrasting charismatic and rational-bureaucratic forms of criminal authority. Third, I discuss the “why?” of governance, distinguishing several logics or motives that may lead criminal organizations to provide (or not) governance for non-members. Finally, I explore how criminal governance intersects with the state, refining the concept of crime–state “symbiosis” (Lupsha Reference Lupsha1996) and distinguishing it from neighboring concepts. I conclude with a key implication: just as criminal governance cannot be understood in isolation from the state, state governance can no longer be fully understood apart from criminal governance (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2006; Barnes Reference Arias and Barnes2017; Varese Reference Varese2010).

What Is Criminal Governance?

Definitions, Scope Conditions, and Sources

I propose a simple, broad definition of criminal governance: the imposition of rules or restriction on behavior by a criminal organization. This includes governance over members, non-member criminal actors, and non-criminal civilians. Throughout, I use “criminal organization” (CO) as an atheoretical, inclusive descriptor to refer to any group engaged in criminal activity. I thus avoid the perennially contested question of what is, and is not, “organized crime” (e.g., Schelling Reference Schelling1971; Varese Reference Varese2010). While governance is rightly seen as a key characteristic of organized crime (e.g., Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2018), it is practiced by a wide variety of groups, including local street gangs and diffuse prison-based organizations. Whether the type, size, or sophistication of COs correlate with their governance practices are empirical questions about which a conceptual framework should remain agnostic.

These definitions hinge on the word “criminal”, which is contentious not only analytically but politically. A simple legal definition—say, “in violation of one or more laws”—is both overly inclusive, because rebels also violate laws, and naive to the ways that states sometimes criminalize broader populations and spaces (e.g., Simon Reference Simon2007; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017). Moreover, states are generally far more willing to negotiate with “political” than “criminal” armed groups, based on the perceived moral superiority of ideological motives over purely economic ones. This makes criminal status itself a field of real-world contention, with states undisposed to negotiation labeling insurgencies as “narco-terrorists” on the one hand and drug-cartel PR campaigns avowing political objectives on the other.Footnote 3 Scholars too, of course, find distinguishing between “greed and grievance” theoretically and empirically difficult. Focusing on armed groups’ stated objectives offers some traction—since COs rarely seek formal state power—but nonetheless produces borderline cases, such as “lapsed” insurgent groups primarily engaged in illicit economic activities.

Scholars of criminal governance need not settle these thorny questions; they should, however, remain attuned to the politics surrounding “criminal status” in their cases. Many COs do not contest, and may even embrace, their status: Brazil’s PCC, for example, calls itself the “Party of Crime.” Murkier are armed groups like vigilantes, autodefensas, and paramilitaries that position themselves, and may be seen by segments of the population, as “lesser evils”. Whether groups that blur the line govern differently than clear-cut COs, and how the politics of “criminal status” plays into such differences, are important avenues for research.

Another important scope condition concerns “governance.” Provision of public order and enforcement of property rights undoubtedly constitute governance, but other common CO activities, on their own, may not. Can a criminal group that extorts residents without providing any services or imposing any rules be said to govern? Or a drug gang that occupies a street corner but otherwise imposes no rules on other traffickers or residents? One reason to exclude such cases is that stretching the concept to include them dilutes the puzzles of governance. It is not surprising that gangs predate, control the physical space where they conduct illegal transactions, or regulate those transactions. What is puzzling is that they also provide public goods and impose rules on additional actors.

As such, I adopt the following criterion: governance occurs when the lives, routines, and activities of those governed are impinged on by rules or codes imposed by a CO. Pure extortion, where the only rule is “pay,” does not count. Conversely, and less plausibly, providing public goods while imposing no rules at all is closer to philanthropy than governance. These are theoretical limit cases; few COs, I suspect, engage in either pure extortion or philanthropy. Still, scholars may end up revising these scope conditions if real-world cases need to be accommodated.

To illustrate the concepts developed here, I draw empirical examples from multiple sources, including extant scholarship, journalistic accounts, and my own research in Latin America. The latter spans multiple projects—some collaborative—including hundreds of interviews, fieldwork in dozens of informal urban communities, and visits to more than twenty prisons in Brazil, Colombia, and El Salvador.Footnote 4 From these combined sources, I chose examples that illustrate the empirical range of governance activities, institutions, styles, and functions; in general, I make no claims of examples’ novelty or representativeness.

Situating Criminal Governance

Criminal governance resembles, but differs critically from, other forms of governance. COs’ elaborate bookkeeping, recruitment, and internal management practices draw parallels to corporate governance. When gangs provide public security and dispute resolution, while imposing rules on and sometimes taxing residents, it is tempting to treat them as “mini-states” (e.g. Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997). Alternatively, we might note the lack of legal property rights and trust in illicit markets (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993), and conceive of criminal groups as spontaneous, non-state sources of governance (e.g., Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). Finally, state violence against COs, who in turn often frame their governance over marginalized civilians as a “struggle” against oppression (e.g., Lima Reference Lima1991), suggests criminal governance as a diminished subtype of rebel governance. These approaches each yield some insight, but are misleading or incomplete in important respects.

First, criminal governance is more than corporate governance. Of course, COs generally seek to earn illicit profits, and states often invoke COs’ allegedly “economic” interests to distinguish them from “political” or ideological armed groups. The most sophisticated COs have complex internal structures, management praxes, recruitment strategies, and “corporate cultures” that resemble those of licit firms. Moreover, the relationship among COs can be analogized to licit firms competing for market share: we can usefully distinguish criminal monopoly from oligopolies both competitive (violent) and collusive (pacted or peaceful). Yet unlike most licit firms, COs’ governance extends beyond employees to wider criminal networks and often large civilian populations.Footnote 5 It cannot be assumed that such governance is undertaken purely as a means of maximizing profits, at least not in any immediate sense.

Organized crime is not exactly state making either. Scholars have long compared formal state governance with organized criminal activity (e.g., Blok Reference Blok1974; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1969; Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985), illuminating key aspects of state formation. Yet these now-familiar metaphors can impede a clear understanding of criminal governance by tempting scholars to simply reverse their direction. If states are essentially protection rackets, one might argue, then protection rackets must essentially be states. If the logic of stationary banditry drives autocrats’ approach to taxation (Olson Reference Olson1993), then autocratic extraction must be the goal of bandit rule (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). If gangs are “primitive states” (Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997) then we might expect warfare among them to produce “gang-building” and evolution toward more legitimate, less coercive forms of rule.

Such assertions may be accurate in specific cases, but they overlook a central fact: criminal governance occurs in settings where states—often quite powerful states—already exist. Indeed, states determine what is criminal, a precondition for the rise of COs (Koivu Reference Koivu2018). By definition, COs face some degree of state repression, repression which often structures the very spaces they govern: illicit markets and prisons are prime examples. Above all, and unlike Tilly’s proto-states, criminal groups rarely challenge existing state authority wholesale. Rather, they govern in the interstices of state power (Yashar Reference Yashar2018), pockets of low state penetration typically surrounded by areas of firmer state presence, and which state forces can enter at will, though not always without violence. Thus, the view of COs as “mini-states” within their area of influence is often overblown, concealing as much as it reveals (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993).Footnote 6 Criminal governance cannot be understood apart from the state, its policies, its coercive apparatus, and its relation to citizens.

Criminal organizations’ opposition to the state parallels that of insurgencies, and rebel governance is perhaps the closest cognate phenomenon to criminal governance. Kasfir’s characterization of the study of rebel governance is equally true of criminal governance: “[It] analyzes the behavior of governments formed and operating under armed threat without benefit of sovereignty” (2015, 24). For both insurgent and criminal groups, Manichean antagonism with the state is just one endpoint along spectra of “wartime political orders” (Staniland Reference Staniland2012) and “crime–state relations” (Barnes Reference Barnes2017) that include mutual toleration and even active collaboration. Indeed, for both fields of study, paramilitaries and pro-government militias lie in a grey zone precisely because the state seems to outsource its core governance function to them (Kalyvas and Arjona Reference Kalyvas, Arjona and Rangel2005). Another key similarity is negative cases: some rebel and criminal groups could govern civilians, but do not. This makes the question “Why govern?” more relevant for rebel and criminal governance than for corporate or state governance.

Yet criminal and rebel governance differ in key respects. First, COs generally lack rebels’ overarching goal of “competitive state-building,” which renders insurgency “fundamentally distinct from … banditry, mafias, or social movements” (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006, 218). Rebels, even when they govern in order to extract rents, “differ from criminal gangs engaged in similar activities because rebels hold territory with the political intention of taking over the state, seceding, or reforming it” (Kasfir Reference Kasfir, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015, 23). Indeed, these “political intentions” critically influence how states categorize and treat armed groups. Murky limit cases aside, countless COs govern civilians without hope or intention of obtaining formal state power. Relatedly, rebel governance occurs amidst civil war, typically—and for many scholars, necessarily—in “liberated zones” of strong territorial control (e.g., Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Kasfir Reference Kasfir, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015; Weinstein Reference Weinstein2006). Criminal groups rarely establish exclusive control. Their authority usually overlaps, often quietly, with the state’s; COs may even welcome state governance in domains like health and education. Such complementarity, I will argue, permits “symbiotic” relationships between criminal and state governance; these seem quite unlikely for rebel governance. Finally, scholarship on rebel governance emphatically limits its scope to rule over civilians (Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Kasfir Reference Kasfir, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015), while that on criminal governance has—rightly, I argue—included governance over COs’ own members and over non-member criminal actors and markets.

These are differences of degree. Not all insurgents truly hope to win state power, while some COs, perhaps, do (Pablo Escobar was famously elected to Colombia’s congress in 1982). “Rebel governance,” Huang’s (Reference Huang2016, 52) systematic review shows, “can emerge very rapidly with only tenuous territorial control,” while some COs do achieve strong territorial control, such as urban “no-go zones” that state forces can only enter via militarized offensives. Finally, for both rebel groups and COs, distinguishing between true members, affiliates and sympathizers, and uninvolved “civilians” can be theoretically and empirically difficult. At the limits, rebel governance might well approximate criminal governance in key respects.

Nonetheless, the modal cases of rebel and criminal governance look quite different. Precisely because criminals so often govern without state-building aims, overtly political ideologies, or strong territorial control, its study may yield new perspectives on the more established field of rebel governance. For example, Weinstein (Reference Weinstein2006) argued that insurgent groups that formed with “economic” rather than “social endowments” (and hence whose early joiners were more “opportunistic” than “activist”) ultimately use more violence against civilians. By this argument, COs, whose endowments are presumably primarily economic, should be systematically violent toward civilians. This does not seem to be the case.

Dimensions of Criminal Governance

Who Is Governed?

Scholarship on “criminal governance” has adopted a wide purview, including COs’ surprisingly sophisticated internal governance over members (e.g., Leeson and Skarbek Reference Leeson and Skarbek2010), as well as over a wider populations of non-member criminal actors, often within a specific illicit market, ethnic group, or territory (e.g., Feltran Reference Feltran2010; Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). Still, studies of “criminal governance” usually focus on CO rule over civilians (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2006; Leeds Reference Leeds1996; Ley, Mattiace, and Trejo Reference Ley, Mattiace and Trejo2019). Since this phenomenon so tightly parallels the concept of “rebel governance,” and is of such normative and substantive importance, it is tempting to restrict the scope of “criminal governance” to governance over civilians. This would be a mistake.

Instead, I distinguish three levels of criminal governance based on who is governed: CO members, non-member criminal actors, or non-criminal civilians (figure 1). There are two reasons for this capacious definition. First, the boundaries between levels in figure 1 are empirically and conceptually porous. Second, the mechanisms of governance at one level often spill over or are deliberately extended to other levels. Jointly studying governance at all three levels, while remaining sensitive to their differences, can illuminate key dynamics. In particular, COs that govern at only some levels constitute important negative cases of governance at other levels.

Figure 1 Who is governed? Subtypes of criminal governance

For internal governance by COs over their own members, the interesting question is not “why govern?” but “how?” COs face organizational challenges due to their illegality and have developed a rich variety of internal-governance mechanisms in response. Moreover, when COs come to govern non-members and civilians, it is often by extending or adapting their internal governance mechanisms. Even scholars primarily interested in CO governance over civilians can gain insight by studying how COs are internally organized, and why some do not govern civilians.

COs may also govern non-member criminal actors; these may be autonomous actors in a specific illicit market (say, retail drug dealers), non-member inmates housed in a gang-controlled prison, local street gangs subjected to the rules and taxation of a prison-gang, or even the criminal underworld writ large. I refer to this as criminal-market governance, although the object of governance need not be a market in the strict sense. Here both the why and the how of governance are puzzling: COs must have both motives and means for governing autonomous actors and groups that are, by definition, not law-abiding. Such governance is central to influential definitions of organized crime, flowing from Schelling’s seminal insight that “organized crime is usually monopolized crime” (Reference Schelling1971, 74). Campana and Varese, following Schelling, argue that a defining characteristic of organized crime is the attempt “to govern the underworld” (Reference Campana and Varese2018, 1383).

Finally, criminal–civilian governance denotes CO rule over people not directly involved in criminal activity. I propose “gang rule” as a handy (albeit imprecise) label, useful given its prominence. Millions of citizens live under some form of gang rule, with untold implications for state formation, democratic consolidation, economic development, and more. Were criminal governance limited to internal or criminal-market levels, it would still matter, but it would not be of first-order political and ethical importance. Moreover, gang rule is fundamentally puzzling: why do supposedly profit-driven COs with no claims on formal state power get into the business of governing civilians?

In practice, distinguishing CO members from other criminal actors and civilians can be difficult, Gang induction, for example, often involves intermediate phases of “hanging out” and provisional status, and informal neighborhoods almost by definition involve residents in economies and living arrangements of ambiguous legality. Family members—particularly spouses—of CO members often fall between levels, subject to more rules than average civilians, but less than members or criminal affiliates (e.g., Godoi Reference Godoi2015). CO governance at one level can thus easily spill over into others. For example, the PCC’s prohibition of talaricagem (sleeping with a member’s partner) necessarily extends beyond members to broader communities.

More importantly, governance mechanisms and institutions developed at one level can be deliberately adapted and extended to others, as the PCC’s tradition of debates (tribunals) illustrates. Debates began as part of the PCC’s internal governance within prison; they fostered collective decision-making through argumentation rather than rank-pulling. The practice extended beyond baptized members to the larger inmate population, as a means not only of resolving specific conflicts, but of embodying and inculcating collective norms (e.g., Biondi Reference Biondi2016; Marques Reference Marques2010). When the PCC began prohibiting unauthorized violence in the urban periphery, debates became a critical governance institution, requiring consensus among a jury of imprisoned PCC leaders to decide which executions would be allowed (Feltran Reference Feltran2010, 65). But residents may also ask street-level PCC disciplinas (disciplinarians) to convoke debates over more quotidian disputes. Indeed, a police detective complained that “cases of neighborhood squabbles and even domestic disputes … are clogging up our wiretaps, which are capturing fewer conversations about major PCC actions” (Redação Terra 2008).Footnote 7 Studying institutions like debates at all levels of governance can thus illuminate their origins and effects.

What Is Governed?

Unlike insurgents engaged in competitive state-building, COs need not contest all aspects of state governance. Instead, CO rule over civilians is often narrow and discontinuous, regulating (say) property crime and contact with police but leaving other domains like interpersonal violence or electoral politics untouched. Similarly, criminal-market governance often covers some illicit activities but not others. In short, COs can govern a lot or a little, along a host of dimensions.

Figure 2 groups some widely observed dimensions by broad governance function—policing, judicial, etc.—and suggests empirical ranges of variation for each, from low to high levels of governance. I summarize these here, and provide further details based on extant research in the online appendix. While some dimensions seem logically related—for example, effectively prohibiting interpersonal violence likely entails providing dispute resolution— whether and how they are correlated remain empirical questions. Similarly, observing low levels of governance does not imply that COs lack the capacity to govern more vigorously; they may simply choose not to.

Figure 2 What is governed? Dimensions of criminal governance, by function.

Note: Examples of governance activities are cumulative, e.g., High levels include activities at Low and Medium levels.

Future research should add to and reorganize this list as appropriate. Building and refining a collective compendium of criminal-governance activities is critical to the evolution of this research agenda, because it helps researchers know what to ask about. For example, interviews in Medellín revealed the ubiquity of loansharking by local gangs (Blattman et al. Reference Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobón2020), leading me to ask about, and learn of, similar though rarer moneylending in Brazil. Even when we find no evidence of an item from the list, it is good to have asked. A confirmed zero is different than missing data, and researchers, by identifying what their cases are negative cases of, can better situate them in the broader universe of criminal governance. “Asking anyway” is particularly important where gang rule appears weak and constrained: verifying that gangs are not engaged in certain forms of governance is an empirical finding in itself.

Policing and enforcement functions.

COs prohibit and, to differing degrees, punish and prevent a series of behaviors. Prohibiting theft and robbery within and sometimes near the communities that COs operate in is quite common, reflecting the Lockean centrality of securing property to governance in general. Perhaps more unique to criminal governance, many gangs assume responsibility for preventing and punishing rape and sexual abuse, especially of children. Indeed, residents seem to demand that local governing groups deliver swift and often brutal punishment for sex crimes (Gutiérrez-Sanín Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015), giving COs an inherent advantage over states (Caramante Reference Caramante2008). COs may also regulate domestic violence to varying degrees, and some enforce broader rules around sexual behavior and harassment. A trafficker in Recife, Brazil, for example, reported that among the “laws” his gang posted in his community was “Don’t look at someone else’s woman, even if she’s not a gang member’s, just a resident’s.”Footnote 8 Female residents in Natal, Brazil reported that after a prison gang had subsumed local street gangs under its banner, rules against catcalling were imposed, making it much easier to transit freely.Footnote 9

COs also commonly regulate interpersonal violence, particularly homicide; ban contact with authorities (sometimes known as the “law of silence” or omertá); and restrict movement in, out, and beyond a community, including curfews, checkpoints, and bans on visiting rivals’ territory. COs may also regulate firearm possession and use, especially among their own members. COs frequently impose rules around externality-producing behaviors such as loud music, motorcycle use, trash dumping, and other bugbears of community life: in one CO-controlled favela in Fortaleza, Brazil, a hand-painted warning read “each group of gossipers = 10 beatings.”Footnote 10 Some COs ban colors, hairstyles, music, slang, and hand signs that reference rivals, including on social media. Many COs ban homosexuality among members, and some may regulate civilian sexual behavior. Though rare, COs have been known to regulate religious practices. In Rio, for example, the Terceiro Comando Puro CO prohibited Afro-Brazilian religions like Ubanda and Candomblé, with violent attacks on priests and houses of worship filmed and circulated online as warnings (O Dia 2017).

Judicial functions.

Resolving disputes is a basic attribute of authority (Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009), and a common dimension of criminal governance. COs’ judicial mechanisms vary widely in sophistication and institutionalization. At one extreme, a single local boss (or designated subordinate) may hand down arbitrary decisions. At the other, exemplified by the PCC, institutionalized jury trials apply standardized norms, graded punishments, and even “legal” precedents (e.g., Telles and Hirata Reference Telles and Hirata2009, 54), with past infractions and punishments meticulously recorded in detailed personnel files and duly taken into account (Lessing and Denyer Willis Reference Ley, Mattiace and Trejo2019). COs may also offer contract enforcement and debt collection services to third parties.

Because they often begin as part of internal CO governance, judicial institutions represent a key domain for studying all three levels of governance conjointly. How far COs extend these functions to non-member criminal actors and civilians varies considerably, even among those with significant capacity. For example, in a favela stronghold of the powerful Família do Norte (FDN) prison gang in Manaus, Brazil, residents told me that the FDN only gets involved in “very serious fights, or if it involves somebody from the drug trade,” and that in general, “People resolve things on their own, or go to the police. The [FDN] doesn’t care.”Footnote 11 Even the PCC has sought to restrict its sophisticated dispute-resolution services to “those who identify as being from the world of crime”, provoking—incredibly—controversy among residents (Feltran Reference Feltran2018, 175).

In some cases, sentences have a “restorative” quality: recovering stolen items, forcing infractors to pay damages or “make things right” with the community. For example, one Medellín resident reported that “you see people , , , picking up trash and sweeping the streets, it’s because they screwed up … when [gang members] don’t give them a beating, they make them do community service.”Footnote 12 Some COs allow or compel victims to carry out physical punishments against their aggressors; the PCC, for example, authorizes vengeance killings by successful plaintiffs (Feltran Reference Feltran2010, 67-8). How commonly COs—who are often deeply embedded in tight-knit communities—implement restorative forms of justice is a fascinating question for future research.

Fiscal functions.

Taxation is so central to state-formation (e.g., Levi Reference Levi1989; Olson Reference Olson1993) that many scholars treat it as a proxy, “the next best thing” to a “perfect barometer of state power” (Slater Reference Slater2010, 35). Among COs, taxation varies more widely. Protection rackets charge for “protection”, hence their similarity to states (Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985); but many governing COs are not protection rackets. In general, the more COs earn from illicit market transactions (especially drug trafficking), the less they rely on taxation.Footnote 13 Taxation further varies in who must pay—more commonly local businesses than residents—and whether COs charge flat fees or attempt to price-discriminate based on income or profits.

On the flip side of taxation, many COs provide public goods beyond basic social order and property rights. COs can—essentially for “free”—solve coordination problems like deciding where to locate a trash dump or a moto-taxi stand. At higher levels of governance, they may provide “cheap” goods that mostly require labor, like street-cleaning and tree-cutting,Footnote 14 or more resource-intensive goods, like recreational facilities, drainage, and public illumination. Many COs also provide welfare benefits for the needy, often in the form of food staples and medication.

COs may also provide financial services at all three levels of figure 1. In Brazil, the PCC’s drug business operates on consignment: thousands of members and non-member affiliates obtain merchandise on credit, with strict repayment schedules. However, the PCC appears not to charge interest, and loansharking to civilians (known as agiotagem) is widely frowned upon as usury by Brazilian COs. In Medellín, by contrast, loansharking (known as gota a gota or paga-diario) is very common among local gangs (Blattman et al. Reference Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobón2020).

Regulatory functions.

COs governance over non-member criminal actors often involves regulating illicit markets, especially drugs: determining who can work where, sometimes setting prices, and—spilling over into civilian governance—deciding which drugs can be consumed where. COs may also regulate criminal activities beyond those they engage in. For example, Rio’s drug syndicates often prohibit bringing stolen vehicles into their territory for disassembly. Legal markets may also fall under CO regulation, taxation, or even direct provision, especially for “universal” goods like food staples and utilities. In Medellín, COs are increasingly involved in the distribution and sale of arepas (tortillas), eggs, dairy products, and even livestock: in 2018 police seized an arepa factory built by the sophisticated Los Triana CO. In Rio, police-linked milícias frequently operate forced monopolies on cooking gas and cable TV, and tax informal transportation (Freixo Reference Freixo2008).

Political functions.

Even among COs capable of coercing voters or candidates, involvement in electoral politics and community governance institutions varies widely (e.g. Arias Reference Arias2006, 2017; Córdova Reference Córdova2019; Leeds Reference Leeds1996). Some simply ignore elections, or endorse a candidate; others act as brokers, selling physical access to voters in areas they control; and some actively coerce voters and even run their own members as candidates. Arias (Reference Arias2017) documents immense variation across multiple settings, finding that CO proximity to officials predicts more direct political involvement, consistent with studies of voter coercion by pro-state militias and paramilitaries (e.g., Acemoglu, Robinson, and Santos Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Santos2013).

Emergency Response.

While this article was in press, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. States everywhere took unprecedented governance actions like imposing lockdowns and regulating economic activity. Though COs’ responses have varied, some with strong governing authority relative to the state appear to be “stepping into the breach”. In Rio, for example, COs have prohibited visits by high-risk foreigners, policed price gouging by supermarkets and pharmacies, provided hygiene supplies to residents, closed businesses (while reducing protection fees where charged), and enforced lockdowns and curfews. These measures constitute sharp increases along some of the dimensions presented here: regulation of licit markets, control over movement, public-goods provision, and so on. Whether they ultimately complement or undermine official emergency-response efforts, and whether emergencies ultimately entrench or erode COs’ governing authority, are both critical avenues for research.

Who Governs, and How? Styles and Structures of Criminal Governance

Different types of organizations are likely to be interested in or capable of different sorts of governance, at different levels. While typologies of COs abound, researchers need not settle thorny questions like whether street gangs are organized crime in order to think about how governance differs systematically across COs. Rather, they should seek to link attributes of the COs they study to the criminal governance patterns they observe (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011).

A few examples bear mentioning. Drug cartels appear to exercise governance in the areas where they exert territorial control, often along trafficking routes and cultivation zones (Duncan Reference Duncan2015; Ley, Mattiace, and Trejo Reference Ley, Mattiace and Trejo2019). Traditional mafias also tend to govern their “home” towns and neighborhoods (Blok Reference Blok1974; Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993) and have had difficulty penetrating areas dominated by other ethnic and racial groups (Reuter Reference Reuter1995). Street gangs are inherently local, their governance activities often tied, and limited, to a specific community (e.g., Hagedorn Reference Hagedorn1994; Jankowski Reference Jankowski1991). Prison gangs, in contrast, have learned to govern at a distance; they organize retail drug markets at city- and even state-wide scales, through criminal-market governance over street gangs (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011) or by subsuming them into larger “corporate” structures (e.g., Cruz Reference Cruz, Bruneau, Dammert and Skinner2011; Hirata Reference Hirata2018). Relatedly, state repression may affect the governance capacities of different COs differently; for example, policies that favor mass incarceration may strengthen or weaken COs depending on whether their locus of power lies within prison or on the street (Lessing Reference Lessing2017). Racial and ethnic composition of COs also matters: US prison gangs are organized along racial and ethnic lines, limiting their street-level governance to co-ethnic neighborhoods, while Brazil’s prison gangs are multiracial, permitting city-wide hegemony. COs’ sources of income are also likely to affect governance.

Styles and quality of governance—of any kind—can be analyzed along many dimensions: how effective, how democratic, and so on. Here, I propose two dimensions as particularly relevant for criminal governance, both flowing from a Weberian perspective: the structure and basis of authority, and its legitimation.

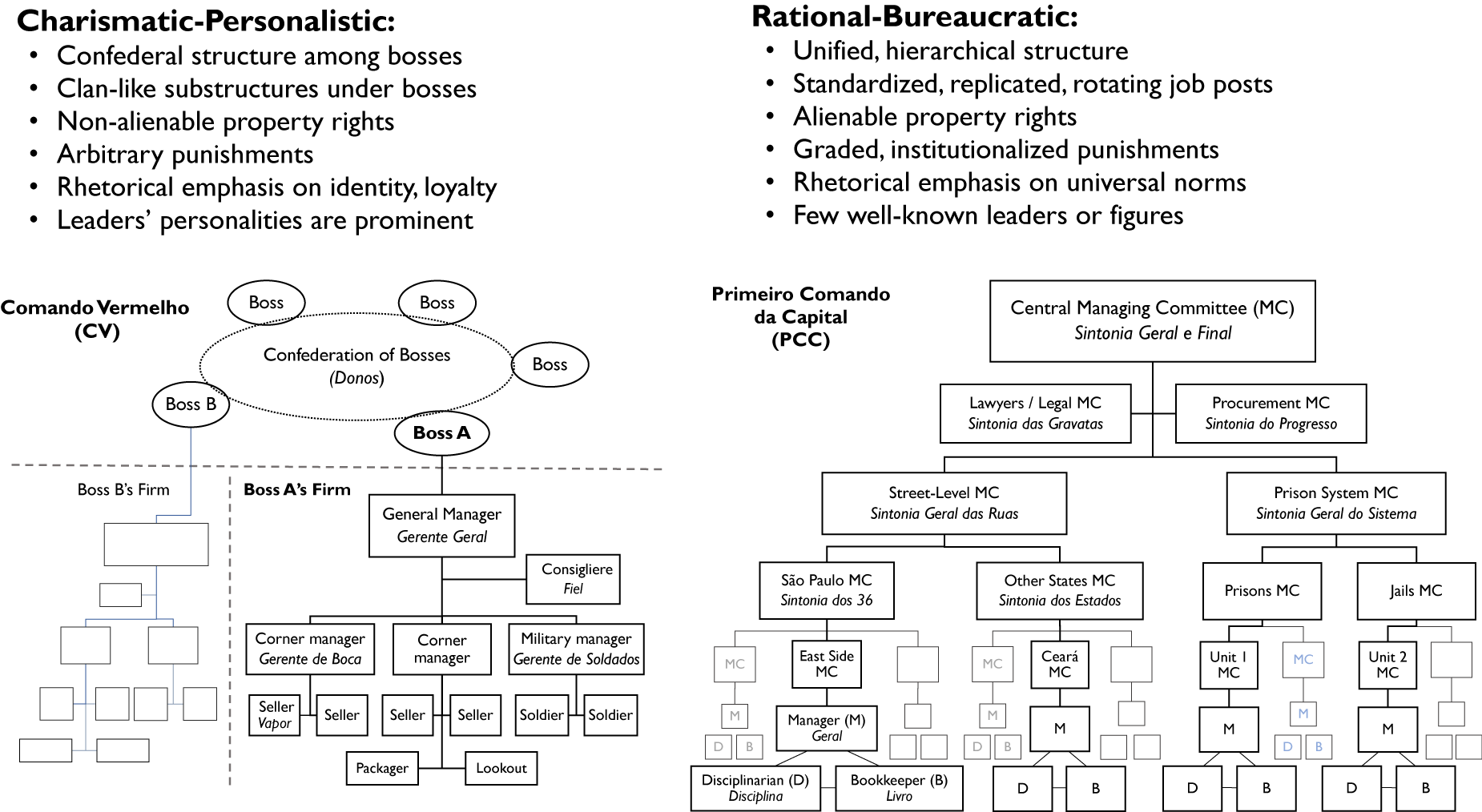

Structure and basis of authority: Personalistic versus rational-bureaucratic.

CO internal governance varies in how authority is structured and exercised, with potentially critical downstream effects on governance over non-member criminals and civilians. COs vary widely in their organizational structures, but as with all organizations, these can be arrayed along a Weberian spectrum from personalistic-charismatic to rational-bureaucratic.

Brazil’s two largest COs, Rio’s Comando Vermelho (CV) and São Paulo’s PCC, approximate these ideal types. In the CV, power is concentrated in and flows from individual bosses (donos, literally “owners”), well-known charismatic leaders with strong, hierarchical control over the favela communities they are from or associated with. Each sits atop, and is a residual claimant on the profits from, a vertically integrated “firm” (firma) that holds a local monopoly on drug retailing. Most donos are incarcerated at any given time, and they appoint trusted lieutenants to run day-to-day operations and remit profits. They ensure loyalty “in the old style of Brazilian patronage, making employees and neighbors dependent on the gifts and benefits they distribute according to their whims and interests” (Zaluar Reference Zaluar2004, 400).

There is no strict hierarchy among donos; rather, they form a deliberative council and “horizontal mutual-protection network” (Misse Reference Misse, Baptista, Cruz and Matias2003). This confraternity wields a certain moral authority, laying down codes of behavior, resolving disputes, and ratifying donos’ “right” to control and profit from illegal activities in their respective territories (Grillo Reference Grillo2013, 78). Yet the CV collective can make only limited claims on donos; it can suggest, but not demand, contributions of financial and military resources to collective causes, for example. Such confraternities of charismatic authority figures may be the modal form of organized crime: Mexico’s “cartels” and the Sicilian Mafia’s Comissione function similarly (Grillo Reference Grillo2011; Paoli Reference Paoli2002).

The PCC is both more and less hierarchical. A deliberative body, the sintonia geral e final, has ultimate authority over a cascade of lower-level sintonias (committees) replicated at each level of management (e.g., neighborhood, municipality, state). The PCC maintains centralized personnel and financial records for its more than 30,000 members, most of whom are located outside its home state of São Paulo (Paes Manso and Dias Reference Paes Manso and Dias2018). In these ways, the PCC resembles a large corporation with branch offices spread across state and even national lines. But the PCC deliberately flattens its hierarchy and depersonalizes authority within it. Each decision-making node has at least two leadership positions, guaranteeing that individuals cannot make “isolated decisions” that might adversely affect the “collective” (Biondi Reference Biondi2016, 83). Most decisions are made by consensus: debates usually involving PCC leaders and those governed, are guided by norms of not “exercising power over others” but rather making one’s case on the merits (Biondi Reference Biondi2016, 82-5).

This contrast in structure and style of authority manifests in markedly different approaches to key institutions like drug-firm ownership and job posts (known in both COs as responsas) (Hirata and Grillo Reference Hirata and Grillo2017). CV donos cannot sell or easily transfer ownership of their firms and the territory they are tied to; as with medieval land tenure, donos’ property rights are not alienable, since they inhere in the personal, charismatic qualities of the donos themselves (Grillo Reference Grillo2013, 70-80). In the PCC, firm ownership does not confer authority over surrounding territory; as such, firms may be owned by non-members (as long as they follow PCC rules), and can be bought and sold freely. In the CV, responsas are managerial or operational jobs within a drug firm’s hierarchy, bestowed by donos on the personalistic basis of consideração (esteem or gratitude). The “gift” of a responsa ties its occupant to the dono and confers a responsibility to protect and expand the dono’s patrimony (Grillo Reference Grillo2013, 72). In the PCC, responsas are essentially political postings, conferring responsibility for ensuring that PCC rules and norms are observed in specific domains; they are assigned by committees, based on individuals’ perceived ability to act effectively in the collective interest (Biondi Reference Biondi2016). Members rotate rapidly through responsas, often taking up postings in neighborhoods, municipalities, and even states that they are not from. Besides guaranteeing continuity amidst frequent imprisonment, transfer, release, and death of members, this system was deliberately designed to depersonalize authority, as revealed by both ethnographic evidence (Biondi Reference Biondi2016) and the sworn Congressional testimony of Marcola, the PCC leader who instituted it (Marques Reference Marques2010).

Adapting Weber’s (Reference Weber1946) classic distinction, I characterize the CV’s model as “charismatic-personalistic” and the PCC’s as “rational-bureaucratic.” Figure 3 illustrates the distinction and summarizes key characteristics of each type. As with most concepts, real-world cases only approximate ideal types. The PCC certainly has its charismatic leaders—including Marcola, his own self-effacing discourse notwithstanding (Marques Reference Marques2010)—many with their own quadrilhas (“crews”) whose internal structure may resemble CV clans.Footnote 15 More broadly, PCC behavior may fall short of its ideals, especially outside of its core territory; as one affiliate in a state the PCC dominates only partially put it, “lots of theory, little practice.”Footnote 16 Conversely, the CV may be selectively emulating PCC centralization: its central council is reported to have begun demanding—not just eliciting—contributions.Footnote 17

Figure 3 Structure and basis of criminal authority: Charismatic-personalistic versus rational-bureaucratic

Note: Charts adapted from Misse Reference Misse, Baptista, Cruz and Matias2003 and Dowdney Reference Dowdney2003 [CV]; and Godoy Reference Godoy2013 [PCC].

While the PCC may be a rational-bureaucratic outlier, careful observation of multiple COs within specific contexts can reveal important, if compressed, variation. Medellín’s shifting panorama of flexible governance hierarchies among armed groups—including neighborhood-level combo gangs, larger mafia organizations known as bandas or razones, insurgent militias, and full-blown paramilitary armies—provides many examples (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Giraldo, Alonso, and Sierra Reference Giraldo, Alonso, Sierra and Romero2007). To take one, Blattman et al. (Reference Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobón2020) report variation in the structure and style of bandas’ governance over combos. Typically, combos are led by a “coordinator” (coordenador), a charismatic leader who, like Rio’s donos, is tied to his neighborhood and a residual claimant on his combo’s rents. Under many bandas, combos retain their local identity and proper names; bandas may appoint or fire specific coordinators, but replacements are usually drawn from within each community. However, the Los Triana banda subsumes its combos into a vertically integrated structure. Combos’ names, local identity, and autonomy are effaced, and coordinators are rotated among neighborhoods by Triana leadership as needed. Thus, although Los Triana may be less rational-bureaucratic than the PCC (as suggested by the fact that “Triana” is a family name), it is probably more rational-bureaucratic than the average banda in Medellín. Identifying such within-context variation among COs may be more fruitful than seeking universal criteria for comparison across contexts. Moreover, by holding multiple factors constant, subnational and submunicipal research designs can help identify CO-level factors that might explain such variation.

Legitimacy.

If “legitimacy”—with its heavy normative connotations—is a perennially contested concept with respect to states, then “legitimacy in criminal governance” may seem downright oxymoronic. Nonetheless, how COs’ authority is viewed, and by whom, are critically important questions. I distinguish two dimensions of legitimacy—“bottom-up” and “top-down”—along which CO governance may vary. The former understands legitimacy as flowing from the consent of the governed, the latter as “officially sanctioned” by other power-holders, such as states in the international system. Top-down views that discount the agency of the governed can be deeply, and to some tastes, “agreeably cynical” (Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985, 171), but these two approaches need not be mutually exclusive. For example, states’ decisions to confer legitimacy on one another might depend on whether each has the consent of those it governs.

Both forms of legitimacy matter to criminal governance. COs are, by definition, de-legitimated by states, who outlaw and presumably combat them. This dearth of top-down legitimacy—even more severe than that faced by insurgencies—generally forecloses not only open negotiation with states but virtually all direct engagement in politics. Instead, COs may rely on more (top-down) legitimate social actors like community leaders or NGOs for mediation (Arias Reference Arias2006), or simply turn to corruption and anti-state violence to keep law-enforcement at bay. Yet important variation in top-down legitimacy of COs within settings may be detected. Arias (Reference Arias2017), for example, finds that the relative legitimacy enjoyed by groups like Rio’s police-linked milícias (who portray themselves as a “lesser evil” than drug traffickers) leads them to engage more actively in electoral politics, striking long-term agreements with allied candidates.

Weber characterized bottom-up legitimacy as “voluntary submission” (Reference Weber1947, 324) in hopes of making it empirically observable, but oppressed people may hide their true feelings. Trying to assess whether civilians meaningfully consent to their armed domination by criminal organizations may seem particularly perverse. If, as Wedeen argues, “conflation of legitimacy with acceptance, acquiescence, consent, and/or obedience is problematic for any political regime” (Reference Wedeen2015, xiv), then it is surely more so for a criminal authority.

Still, the pragmatic question of how willingly subjects comply with the rules and restrictions imposed is of even greater importance to COs than states. Like states, COs reap standard benefits from “voluntary submission”, including less need for costly punishment of transgressors (Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997). But unlike states, COs face an immediate threat from states if disgruntled subjects inform on them to police. True, residents risk severe punishment for openly violating omertá, and accountability may be weaker the greater COs’ coercive and territorial control. Nevertheless, residents may possess important “weapons of the weak”: they can often call anonymous tip lines, refuse to hide CO members during police raids, or make normative appeals, particularly via community elders or religious figures. Even in favelas dominated by Rio’s most powerful drug syndicate, residents regularly use tip-line denouncements to sanction poor gang governance (Barnes Reference Barnes2018). This suggests that virtually all governing COs have strong incentives to keep their subjects minimally satisfied, and that failure to do so may manifest in observable ways.

While establishing absolute measures of legitimacy is daunting, detecting variation among COs from the same setting, or within COs over time, is often feasible. In Rio, for example, Dowdney (Reference Dowdney2003) reports residents’ complaints of increasingly cruel and coercive governance, as rival prison-gang invasions left non-locals as governing authorities. Conversely, favela residents in Natal, Brazil, told me that the takeover of their community by a single prison gang, subsuming myriad incumbent street gangs, led to significant improvement in the quality of governance: “Now there is peace and respect; our only problem is the police”.Footnote 18 While subject to severe selection biases, since the most disgruntled may be the most terrified to speak, anecdotal data can still stake out a range of variation. For example, enumerators for a business-extortion census in Medellín told me that respondents in the community we visited were far more positively disposed to paying the vacuna (protection fee, literally “vaccine”) than in the previously visited community, where business owners “vented” deep frustration at high fees and inadequate protection.Footnote 19

All things equal, bottom-up legitimacy is likely reduced by any taxes (i.e., protection fees) charged to residents and businesses, and by COs’ use of violence to resolve disputes and achieve their desired outcomes (Arias Reference Arias2006; Barnes Reference Barnes2018), though residents may tolerate or even support high levels of both if overall CO governance meets shared expectations of behavior and performance (e.g., Gordon Reference Gordon2019). For example, a Natal resident expressed opprobrium at the local prison gang’s lethal punishments of infractors, but recognized this as a “necessarily evil” to produce the security, orderliness, and respect for women that the gang’s takeover had brought.Footnote 20

For Weber, these shared expectations—the basis on which authority is accepted as appropriate by the dominated—vary with the structure of authority: charismatic rulers are legitimated by virtue of their unique, personal characteristics; bureaucrats by virtue of adherence to universal rules and norms and efficacy in carrying out assigned duties. An intriguing question is whether those subject to criminal governance judge governing COs on different bases depending on their structure of authority. Recent work on the PCC suggests that people under rational-bureaucratic governance indeed judge local leaders against universal normative standards (Biondi Reference Biondi2016; Feltran Reference Feltran2018).

Why Govern?

COs’ reasons for internal governance are similar to any organization’s: to efficiently organize activities, avoid schisms, create operational capacity, and so on. CO governance of criminal markets and underworlds is more puzzling, since many COs never make the attempt. More puzzling still, why do COs govern civilians, to differing degrees, along differing dimensions? Given the impact of gang rule on civilians’ lives, these are preeminent questions for the criminal-governance research agenda. As raw material for theory-building and -testing, this section distinguishes some plausible logics motivating criminal governance, of both non-member criminal actors and civilians. Real-world cases are likely to involve multiple logics, possibly ones not anticipated here.

Why Govern Other Criminals?

The conventional wisdom in organized crime scholarship is that COs govern non-member criminal actors in order to tax them. While compelling, this explanation is not exhaustive. Some prison gangs, for example, do not tax the prison masses, suggesting alternative motives like self-protection. Beyond this, many COs claim to govern the criminal underworld (or parts of it) for ethical, political, or ideological reasons. Of course, such motives may ultimately serve COs’ interests, and so could be lumped into an all-encompassing conception of “rent-seeking.” Instead, I disaggregate these logics, since the conditions under which they come into play are likely to vary.

Rent extraction/extortion.

Schelling famously identified organized crime with the extraction of tribute from other, presumably unorganized, criminal actors: “Organized crime does have a victim … the man who sells illicit services to the public. And the crime of which he is the victim is the crime of extortion” (Reference Schelling1971, 76). Schelling focused on protection from police as the source of COs’ extortionary power, but the same logic applies when COs govern, pacify, and streamline illicit markets like the retail drug trade, creating a taxable economic surplus (e.g., Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). This logic predicts that variation in criminal governance tracks the tradeoff between COs’ costs of provision and their potential gains from taxation.

Self-protection.

Many prison gangs arise as self-protection pacts, to ward off predation by other inmates and abuse by officials. Even if establishing social order among the prison masses yields additional benefits for gang members, they enjoy physical security as much as the larger inmate population. This motive helps explain governance in the absence of taxation or extortion. For example, whereas California prison gangs reportedly tax all inmates in the wings they control (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011), Brazilian prison gangs generally do not. The PCC, known for charging a monthly membership fee, exempts unbaptized “affiliates” and other inmates (Paes Manso and Dias Reference Paes Manso and Dias2018). Similarly, mafia neighborhoods are notoriously safe, since bosses prohibit robbery and violent crime where they live; since this leaves no criminal rents to tax, the primary motive is likely protection of members and their families.

Political leverage.

COs may govern criminal populations in part to win loyalty and build political constituencies, ultimately amassing leverage against the state. This logic is pronounced among prison gangs. For example, Brazil’s CV, after establishing hegemony within its home prison, quickly mobilized the inmate population in hunger strikes against guard abuse—a strategy gleaned from the leftist militants with whom its founders were imprisoned (Lima Reference Lima1991). American prison gangs have also effectively organized hunger strikes to protest overcrowding and solitary confinement (Reiter Reference Reiter2014). A more aggressive tactic is instigating strategic prison rebellions, often involving hostage-taking, to force official concessions. While not all rebellions are planned, some clearly are: the PCC’s 2006 “mega-rebellions” occurred simultaneously in ninety-six different prisons scattered across multiple states, coordinated by cell phone.

COs with street-level governance capacity may also orchestrate public protests, violence-reducing truces, or chaos-causing attacks by criminal actors as part of “violent lobbying” strategies. The state of Ceará, Brazil offers examples of all three. In 2016, prison gangs announced a “Union of Gangs,” consolidating power over myriad street gangs, and ordered previously warring members to join in a peaceful “Crime March” (Alessi Reference Alessi2016). The truce was short-lived, but Ceará’s prison gangs came together again in 2019, launching a months-long wave of bombings and bus-burnings—mostly carried out by non-member youths—to protest the government’s plan to end segregation of prisons by gang.

Normative reasons.

COs often espouse ethical or even ideological reasons for governance. Prison-gang prohibition of rape, for example, is generally presented as a moral victory over an execrable practice. Virtually all Brazilian prison gangs have adopted a version of the CV’s motto “Peace, Justice, and Liberty”, and regularly frame their actions as part of a “struggle” (luta) against official injustice and depraved rivals. Gang leaders in Medellín, with long-standing ties to the country’s anti-communist paramilitaries, often present their governance activities as high-minded efforts to rid poor neighborhoods of “subversion.”Footnote 21

Whether normative concerns truly motivate costly governance activities or are post-hoc justifications is often unclear, in part because governance may also yield economic, political, and strategic advantages. For example, some scholars argue that the PCC’s ban on killing was a normatively motivated response to a vicious cycle of homicides among young men (e.g., Feltran Reference Feltran2018); the resulting collapse in violence nonetheless gives the PCC critical bargaining leverage. Indeed, this intermingling of normative and strategic concerns informs its slogan “Peace among thieves; war on the state.” Despite such ambiguity, empirical variation in the sorts of normative appeals COs make may offer clues to the extent of their sincerity.

Why Govern Civilians?

Taxation/extortion. If states provide order, security, and governance with the ultimate aim of maximizing revenue-extraction from subjects (e.g., Levi Reference Levi1989; Olson Reference Olson1993; Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985), perhaps COs do as well. Many COs indeed function as protection rackets, whose customers often include civilians (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993). However, COs with other income sources—especially drug trafficking—often abstain from taxing civilians, suggesting additional motives.

Reduce exposure to policing and repression.

Another common explanation of gang rule is that it minimizes police incursions and patrolling in CO territory. This logic obviously underlies omertá (the “law of silence”), as well as prohibitions on crimes that draw police attention, such as homicide, sexual violence, and brawls. COs may also regulate activities that could lead residents to call the police, such as theft, domestic violence, and public drug consumption. Supplying dispute resolution, restorative justice, and enforcing community norms offers residents convenient alternatives to state authorities for quotidian problems. COs broader “hearts-and-minds” efforts to foster loyalty, sympathy, or even partisanship among residents may also flow partially from this logic, if loyal residents are more willing to hide CO members and merchandise, or facilitate their flight, during police raids.

Political leverage.

Instilling loyalty may also help COs mobilize residents to engage in protest activities, such as when Rio traffickers order residents to “go down the hill” en masse to protest police killings, or when Mexico’s Família Michoacana drug cartel organized highway blockades to protest the deployment of army troops to the state (Reforma 2009). Such civilian-backed protest activities, even if partially coerced, can help COs extract policy concessions from leaders, and complement more violent lobbying.

Increase profits.

For COs engaging in illicit economic activity, especially retail drug trafficking, governance is likely good for business. Beyond preventing loss to police repression, COs have incentives to make customers feel safe enough from property and violent crime to approach points of sale. Some public-goods provision requires outlays but may nonetheless increase CO profits: in Rio, drug syndicates commonly throw weekly bailes, dance parties with DJs or live bands—an important source of entertainment in neighborhoods bereft of cultural options—at which they socialize and sell drugs (Grillo Reference Grillo2013).

Crowd out or deter potential competitors.

This logic may help explain situations where COs govern but do not seem to earn large rents in return. Just as community support for the local CO may reduce that CO’s exposure to police, it may, by the same token, make it harder for a rival CO to invade or infiltrate. Similarly, CO leaders might fear that disgruntled civilians could abet an internal coup.

Other non-material benefits.

COs may also be motivated by status concerns, especially access to women. While generally understudied, anecdotal evidence indicates that sex plays an important role in gang recruitment and CO activity. A key empirical question, though, is whether status accrues only or more to COs and members when they govern. If simply being a flush drug trafficker wins one status, then this logic cannot explain why COs govern.

Some COs also express a sense of duty to the community, especially if members are locals. Failing to prevent or punish certain crimes—especially rape and pedophilia—may bring a sense of shame or impotence to local COs, though these may overlap with strategic factors: Gutiérrez-Sanín (Reference Gutiérrez-Sanín, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015), for example, argues that Medellín gangs’ failure to punish sexual violence in the 1980s led to widespread civilian disaffection, facilitating their replacement by disciplined guerrilla cadres.

Complementary to internal governance.

Governing civilians may facilitate CO internal governance by providing leaders with opportunities to train and evaluate mid-level managers. For example, a high-ranking Medellín banda leader portrayed governance as a useful barometer of neighborhood combo leaders’ skill, because “you can always see if the neighborhood is organized or not.”Footnote 22 Governing civilians well might also signal COs’ broader capacity to non-members, whether potential recruits or rivals.

Criminal Governance and the State

Criminal governance inescapably undermines the state’s monopoly on the use of force, but is not necessarily diametrically opposed to states’ interests. True, a key motive for criminal governance is keeping the state at bay, sometimes through debilitating anti-state protest and violence. States, in turn, may find criminal governance sufficiently embarrassing and problematic to combat it through muscular interventions that, often enough, fail or backfire. Yet criminal governance can also be inoffensive or even useful to states, whose relationship to COs may blend violence and repression at one level with detente or even cooperation at another. Criminal governance thus enriches the broader study of crime–state relations by illuminating both novel mechanisms of counterproductive state repression and undertheorized, “symbiotic” forms of crime–state cooperation, distinct from the cooperative arrangements most widely discussed in the literature.

Among prominent conceptual frameworks of crime–state relations (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Koivu Reference Koivu2018; Lupsha Reference Lupsha1996; Magaloni, Franco-Vivanco and Melo Reference Magaloni, Edgar and Vanessa2020) Snyder and Durán-Martínez Reference Snyder and Durán-Martínez2009), we can discern three broad types of cooperative arrangements. In the first, what Barnes (Reference Barnes2017) calls “Integration,” COs so penetrate the state that they can use its resources for their own criminal ends. In the other two types, the state remains autonomous from COs, but tolerates their illicit activity in exchange for key benefits (Koivu Reference Koivu2018). In the first, vividly characterized by Snyder and Durán-Martínez (Reference Snyder and Durán-Martínez2009) as “State-Sponsored Protection,” the key benefit is illicit rents, often from drug trafficking.Footnote 23 In the second, what Barnes (Reference Barnes2017) calls “Alliance,” states rely on COs’ coercive force to neutralize third-party threats; this too has obvious state-building benefits (Koivu Reference Koivu2018). These forms can blend together, as when leftist rebels are “bought off” by allowing them to participate in drug trafficking (e.g., Snyder and Durán-Martínez Reference Snyder and Durán-Martínez2009, 270).

Criminal governance does not fit easily into these forms of state-crime cooperation. Governing COs are often highly marginalized or even demonized; this lack of top-down legitimacy makes Integration basically unthinkable. Criminal governance also seems unlikely to sustain State-Sponsored Protection, since many governance activities, such as public-goods provision and dispute-resolution, neither generate rents nor constitute crimes, while others such as extortion are difficult for police to observe, and hence to target for bribe-collection. Finally, criminal governance differs from Alliance in that COs’ coercive capacity—though it may help keep order—does not counter an organized threat to the state.

A more apt concept is crime–state “Symbiosis.” First, however, the term must be clarified. Lupsha (Reference Lupsha1996) introduced it to describe the “evolution” of organized crime’s relation to the state, from predatory to parasitic to symbiotic, emphasizing mutual benefits and dependence. Unfortunately, it has since become a catch-all for virtually any “linkage between [COs] and the state apparatus” (Mingardi Reference Mingardi2007, 57); indeed, Integration, Alliance, and State-Sponsored Protection all fit within this overstretched definition.Footnote 24 Recently, though, scholars of São Paulo have used the term more precisely, to capture a self-reinforcing cycle of mass incarceration and PCC expansion, and the mutually beneficial “pacification” of prisons and periphery that followed (e.g., Adorno and Dias Reference Adorno and Dias2016; Denyer Willis Reference Denyer Willis, Jones and Rodgers2009).

Building on these ideas, I propose a narrower definition of Symbiosis. First, it implies coexistence of separate entities, and so differs fundamentally from Integration. Second, mutual benefits constitute a necessary but not sufficient condition for Symbiosis, since they also play a key role in Alliance and State-Sponsored Protection. Symbiosis differs in that it need not involve strategic, deliberate, or even conscious cooperation. Rather, it evokes distinct organisms each of whose life functions and survival strategies produce things—possibly useless or even harmful to the producer—that are useful or “nutritive” to the other. In blunt biological terms, one creature’s waste may be another’s food. As such, Symbiosis does not require affinity, aligned preferences, or a division of mutually desired resources; it does, however, imply entanglement, a growing together, and mutual dependence that may deepen over time—traits Lupsha (Reference Lupsha1996) emphasized.

Symbiosis thus defined encompasses state actions and policies that inadvertently strengthen COs and fuel criminal governance in particular. Of course, state repression directly generates some of the incentives for criminal governance, as discussed earlier. In addition, anti-crime and mass-incarceration measures can provide resources for CO governance, including recruitment and networking opportunities, incentives for collective action, and even coercive power over those governed (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). Cruz (Reference Cruz, Bruneau, Dammert and Skinner2011), for example, argues that Central American mano dura policies helped prison-based mara gangs extend governance over street-based cliques and, ultimately, civilians; one reason is that mass arrests and harsher sentences increase street-level actors’ incentives for obeying imprisoned gang leaders (Lessing Reference Lessing2017). Even policies designed to weaken prison gangs can be counterproductive: transferring leaders to far-flung prisons can facilitate gang propagation, while harsh solitary-confinement regimes can become badges of honor for leaders (Salla Reference Salla2006, 298) and push COs to develop rational-bureaucratic structures like rotating leadership posts (Dias Reference Dias2009, 138). In all these cases, state policy “worked” in an immediate sense, but in so doing inadvertently fostered criminal governance.

Conversely, criminal governance may, from COs’ perspective, inadvertently facilitate undesirable state actions, policies, or neglect. Most vividly, CO governance over sprawling, overcrowded, and ever-expanding prison systems helps keep mass incarceration itself viable. Such governance clearly benefits imprisoned gang leaders and governed inmates by constraining prison violence. But in so doing, it allows states to maintain large inmate populations while skimping on infrastructure, guards, food and medical services, and so on. In urban peripheries, providing public order and stable property rights may help keep police out—likely one of COs’ prime motives—but it also reduces the costs to states of broader, ongoing neglect of marginalized areas and populations. What are, for COs, unintended consequences of criminal governance can be very valuable to developing states. “Symbiosis” captures this sense of inadvertently—or even unconsciously—mutual benefits.

Conclusion

Despite key contributions across disciplines (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Blok Reference Blok1974; Feltran Reference Feltran2010; HobsbawmReference Hobsbawm1969), criminal governance remains understudied in political science. More common yet less salient than rebel governance, it structures the lives of tens of millions of people in Latin America alone (Lessing, Block, and Stecher Reference Lessing, Block and Stecher2019), without triggering domestic states of exception, international interventions, or even significant media attention. Its ubiquity, variation in intensity and style, and paradoxical relationship to state governance all merit increased engagement. To paraphrase a similar realization of how much disciplinary blinders can hide from view, criminal governance “is no mere outlying peninsula but rather an entire intellectual continent on the map” of governance activity (Hirshleifer Reference Hirshleifer1994).

Mapping this “hidden continent” requires a solid conceptual foundation attuned to criminal governance’s defining characteristic: its embeddeness in a larger domain of state power. I suggested capacious scope conditions for criminal governance, to illuminate common mechanisms of CO-governance over members, non-member criminal actors, and non-criminal civilians alike. I then proposed a series of dimensions based on the who, what, and how of criminal governance, and described their ranges of variation. I proposed hypothetical logics that may help future scholars explain why criminal organizations go to the trouble and expense of providing governance, and to such differing degrees. Finally, I refined the concept of “Symbiosis” to capture a form of crime–state cooperation uniquely relevant to criminal governance.

The embedded quality of criminal governance has two central implications for future research. First, we cannot understand either the causes or consequences of criminal governance in isolation from the state. In some cases—like prison populations and illicit drug markets—muscular state action creates the objects of criminal governance. In other cases, like informal neighborhoods, the state may be sufficiently weak or negligent to allow criminal groups to establish local authority over civilians, yet present enough—just a tip-line call away—to serve as a useful check on criminal authority. The consequences of criminal governance are also bound up with its embeddedness, not only because COs may hobble (Córdova Reference Córdova2019) or distort (Arias Reference Arias2006) civilians’ political participation, but because of the deeper, politically schizophrenic experience of living under a duopoly of violence. Slum residents and inmates alike must navigate a treacherous and shifting landscape of overlapping yet antagonistic authorities (e.g., Arias Reference Arias2017; Biondi Reference Biondi2016; Hirata Reference Hirata2018). Knowing which quotidian problems are the gang’s to solve and which are the state’s can be a matter of life or death. This is a novel form of “low-intensity citizenship” (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993) whose effects on democracy, development, and the rule of law deserve focused study.