In countries where elections are not free or fair, and one political party consistently dominates politics, why do citizens bother to vote? If voting cannot substantively affect the balance of power, why do millions of citizens continue to turn out in these elections? For example, in Algeria’s 2014 elections, where President Bouteflika won his fourth term in office, a reported 11.3 million citizens voted, representing 43.6% of all voting age citizens. In Belarus, 6.1 million citizens—78% of the voting population—went to the polls in 2015 to re-elect longstanding dictator Alexander Lukashenko to his fifth term in office.Footnote 1 And in Cameroon, one of the longest-standing electoral autocracies in sub-Saharan Africa, 4.2 million voters (76.8%) turned out in the 2013 parliamentary and municipal elections, and 3.6 million voted (53.9%) in the 2018 presidential elections. Due to the autocratic nature of these regimes these numbers may not be precise, but it is nonetheless clear that millions of citizens are genuinely participating in these rigged contests. Why do these citizens choose to vote when it is clear that elections will not bring change?

In Cameroon, one can easily find the expected frustration and apathy one would expect in a long-standing electoral autocracy. Across the country, many citizens have withdrawn from a political system that they feel does not change through elections. Seventy percent of Cameroonians believe that if an election were held tomorrow, the ruling party, the Rassemblement démocratique du peuple camerounais (RDPC), would “definitely win a clear majority” of seats in the National Assembly.Footnote 2 Citizens from all different backgrounds profess their frustration with this status quo. When asked if he voted in the 2011 presidential elections, a young man in Kribi, a town in the south long-dominated by the ruling party, stated “I didn’t vote because I don’t believe in the system.”Footnote 3 A woman from the Northwest city of Bamenda, headquarters of the largest opposition party, reported negative feelings about all aspects of the political system: “There is no need to vote because the outcome is already known beforehand. It’s a waste of time.”Footnote 4 Given the current state of affairs, it is not surprising that many Cameroonians feel alienated from the political system.

And yet millions of citizens choose to vote in elections. Amongst the pessimism and disillusionment, there are clear voices of inclusion, patriotism, and hopefulness. Surprisingly, despite the fact that 70% of respondents believed the ruling party will win elections, when asked whether their vote makes a difference in elections, 65% of Cameroonians said it did.Footnote 5 Despite some of our assumptions about the nature of citizenship under autocracy, many citizens are generally satisfied with the political system, and vote to support the status quo. A 45 year-old woman in the West put it succinctly: “We eat, we sleep, there’s no war. I vote RDPC.”Footnote 6 Further, many Cameroonians feel strongly that voting is a civic duty, and, regardless of their political views, are proud to cast their ballot. A 32 year-old Bamoun man in Foumban in the West Region proclaimed that, despite his very strong reservations about the political system,Footnote 7 “I vote only because it’s obligatory as a citizen. It’s my duty. I am not a citizen if I don’t vote.”Footnote 8 Others vote less out of a sense of duty or support for the status quo, but instead because they are oppositional to the regime and feel that voting can improve the level of democracy. As one 50-year-old opposition voter expressed: “Even if elections are not fair, it’s still good to vote because we can participate to expose the irregularity that happens. But if we stay at home it means everything is just fine.”Footnote 9 Clearly, citizens of autocracies possess a diverse set of political opinions, and, perhaps surprisingly, a large number of them express genuine, non-economic reasons for participating in elections, even if they know the elections will not result in political change. I argue that, just like in democratic countries (e.g., Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968), expressive reasons for voting also exist in autocratic countries and can explain variation in voting behavior. Specifically, citizens who believe that voting is a civic duty are more likely to vote than citizens who see voting as a choice, and citizens who believe voting can improve democracy are more likely to vote than those who do not see a connection between voting and democratization.

However, the existing literature on autocratic elections focuses almost exclusively on the importance of material inducements to voting, arguing that citizens most susceptible to clientelistic relationships will be more likely to vote (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Miguel, Jamal, and Tessler Reference Miguel, Jamal and Tessler2015). Discussing elections in Jordan, Lust-Okar (Reference Lust-Okar2006) sums up the existing approach to political behavior in electoral autocracies:

That elections are primarily an area of patronage distribution has a significant impact on voting behavior. Most obviously, voters tend to cast their ballots for candidates whom they think will afford them wasta [patronage], and not for reasons of ideology or policy preferences. They are also more likely to turn out to the polls when they believe that their candidates are close enough to the government to deliver state resources (460).

Others also argue that citizens vote when they approve of the economic performance of the regime, using their participation as a signal of support (Greene Reference Greene2007; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Miguel, Jamal, and Tessler Reference Miguel, Jamal and Tessler2015). While economic factors are important to understanding voting behavior in autocratic contexts, my central argument is that it is unlikely that these forms of inducements are the only—or even the most important—motivation for voting in autocratic elections. In electoral autocracies without mass-based party machines or a functioning welfare system—where the economy is stagnant and many communities lack even basic infrastructure, such as piped water or electricity—after decades of multiparty elections, it seems unlikely that the majority of people vote because they think that high turnout for the ruling party will result in local investments.

Further, the literature on voting behavior in Africa, regardless of regime type, has also focused heavily on the role of patronage-induced voting to the near complete exclusion of the expressive reasons Africans may have for participating in elections. The alternative hypotheses to most studies of patronage voting is policy-based or partisan-based voting, arguing that Africans are not generally motivated by the platforms or policy orientation of a particular party or politician, but instead their capacity to deliver specific goods to their community. In more competitive systems, there is growing evidence that citizens vote to reward strong economic performance for the country in general.

Yet even in Africa’s more consolidated democracies, it is common to hear citizens complain that, regardless of the political party, politicians only show up in their constituencies during elections, rarely delivering any tangible benefits to the community. In Round 6 of the Afrobarometer, 69.3% of all respondents in sub-Saharan Africa indicated that leaders of political parties in their country are “more concerned with advancing their own political ambitions” than “serving the interests of the people” (Afrobarometer, Round 6). While citizens may be aware of the logic of patronage voting, the lack of robust economic development in most countries over the years has likely eroded the credibility of this logic, especially in Africa’s autocracies. As one voter in Bafoussam, Cameroon described: “Only the RDPC [ruling party] Members of Parliament can bring development. The opposition isn’t favored by the government. But really it doesn’t even make a difference because nobody ever brings anything anyways.”Footnote 10 In general, this is likely doubly true in Africa’s autocracies, where ruling parties do not need to win competitive elections in order to remain in power. While Africans may be more likely to vote for reasons of patronage than policy, I argue that the existing literature has largely missed the most important alternative hypothesis to patronage-based voting: expressive voting.

Complicating the assumptions of voting behavior in autocratic elections is important because the existing literature has insisted that hegemonic party regimes are capable of retaining their mass support almost exclusively through their ability to buy off voters. But if, as Magaloni (2006, 149) writes, “vote-buying” does not “[constitute the] essential glue for the maintenance of” the hegemonic party, then we must look to other sources of stability, such as the regime’s ability to invoke the values of patriotism, peace, democracy, and legitimacy. This can help to explain autocracies that have endured considerable economic downturn, such as we have seen in countries like Cameroon, Togo, or Sudan.

Understanding expressive voting is also important because it normalizes and de-exotifies our explanations of autocratic politics in general. Theories of economic voting, particularly those that rely on the explanations of electoral patronage and vote-buying, support a normative narrative that autocracies are illegitimate; they provide an explanation for why citizens would vote to support authoritarianism. Political scientists have inadvertently supported this exotification of autocratic politics by constructing a different approach to understanding political behavior in autocratic regimes (as well as in Africa in general). While it is uncontested that citizens in consolidated democracies vote for expressive reasons, it is harder to imagine that ordinary citizens in autocracies vote for similar reasons, and that voting might constitute a source of pride for citizens of such regimes. Understanding the more banal and ordinary reasons why citizens participate is critical to de-exotifying politics in non-Western contexts.

The first section of this article discusses the scope conditions of electoral autocracies and the case selection of Cameroon. The second section explores existing explanations of voting behavior in electoral autocracies. The third section presents a theoretical framework for understanding non-economic reasons for voting. The fourth section provides the results of an original survey conducted in Cameroon to provide an empirical foundation for this theory. The final section discusses the implications of these findings.

Electoral Autocracies and the Case of Cameroon

I use a broad definition of electoral autocracy, advancing an argument about the sources of electoral participation in hegemonic-party regimes that hold national-level, multiparty elections with an independent opposition in which the chances of an opposition victory are exceedingly small.Footnote 11 As Schedler (Reference Schedler2002a) writes, “Electoral authoritarian regimes neither practice democracy nor resort regularly to naked repression” (36). Instead, they attempt to manipulate the rules of the game as to make these elections unwinnable for the opposition. Electoral autocracies rely on old tricks, such as gerrymandering and electoral fraud, but also use their monopolies on state resources to structurally disadvantage the opposition. Ruling parties use the strength and legitimacy of the state apparatus to monopolize the media and harass and delegitimize opposition parties (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010).

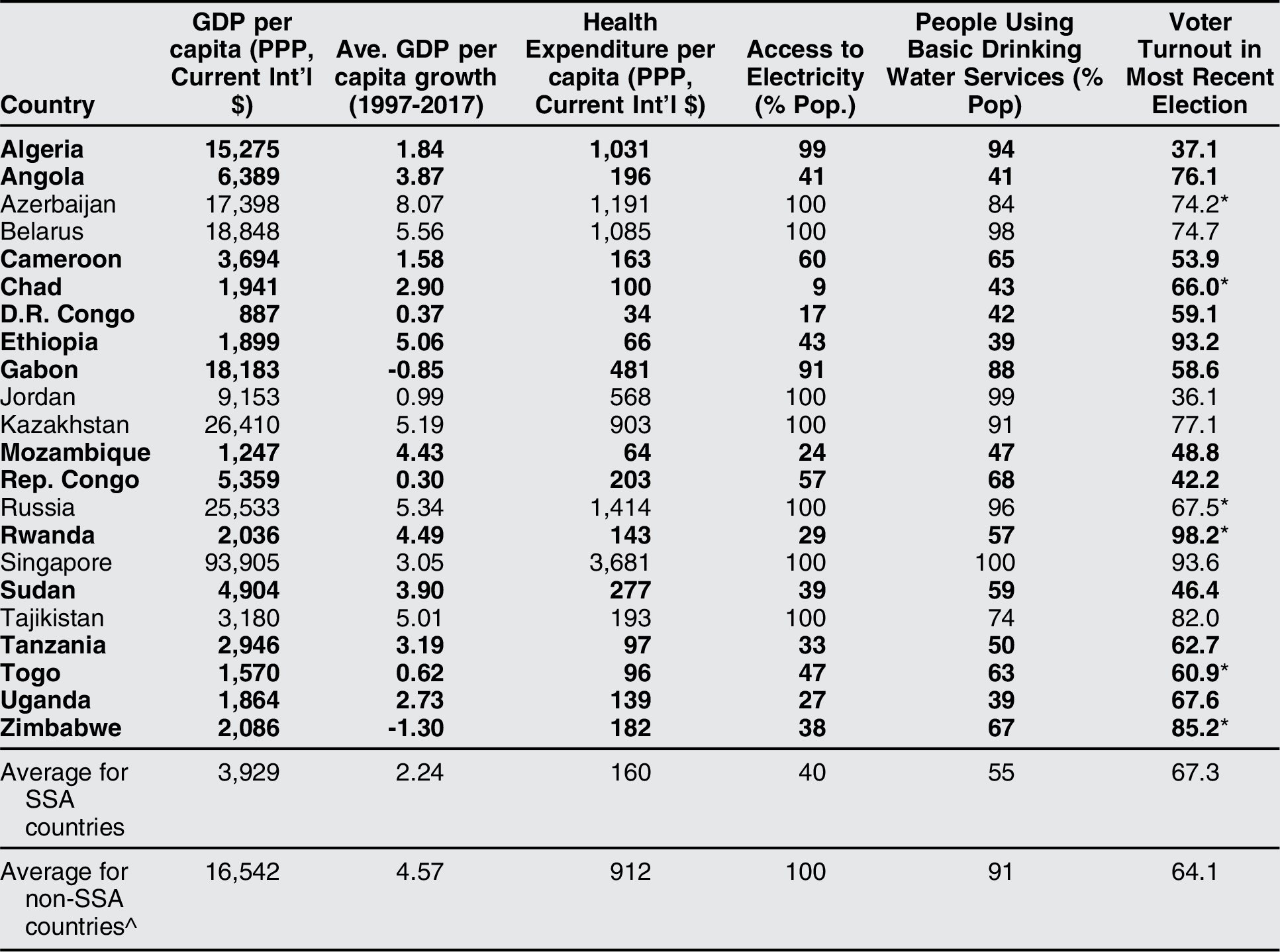

Table 1 presents a global list of contemporary electoral autocracies. It includes any country that has consistently scored a 5 or lower on the Polity IV scale for the past 20 years (1997–2017), had uninterrupted multipartyFootnote 12 national elections during that period, and where the same party won every election—the presidency or the majority of seats in parliament.Footnote 13 For each case, the table includes a number of development indicators taken from the World Bank: GDP per capita, average GDP per capita growth over the past twenty years (1997–2017), health expenditure per capita, and percent of the population with access to electricity and an improved water source. It also includes voter turnout (amongst registered voters) for the most recent election. Cases from sub-Saharan Africa are highlighted, and the averages of sub-Saharan African cases and non-sub-Saharan AfricanFootnote 14 cases are listed at the bottom of the table. Of the 22 cases listed in table 1, fourteen countries are in sub-Saharan Africa. However, despite the fact that most electoral autocracies are found in sub-Saharan Africa, few of our studies of authoritarianism come from the region.

Table 1 Cases of electoral autocracy and contemporary levels of development

Notes: All data from the World Bank Development Indicators Database.

* Presidential election

^ Excluding Singapore

If electoral autocracy is a unique category of regime type, then does it matter where in particular our theories of autocracy are developed? While, arguably, all cases of autocracy can help us to understand politics in other autocracies, it is clear from the data in table 1 that the African regimes are fundamentally different economically from electoral autocracies in other regions of the world, despite, on average, similar levels of political participation. On average, even excluding Singapore, the GDP per capita of non-African electoral autocracies is 4.2 times higher than the average electoral autocracy in sub-Saharan Africa, and average GDP growth in Africa’s electoral autocracies during the past 20 years has been roughly half of that in the rest of the world. This huge gap in economic development would not necessarily matter, except that existing theories rely heavily on economic explanations for political behavior.

With these structural differences in mind, I focus empirically on Cameroon, one of the longest-standing electoral autocracies in sub-Saharan Africa. Cameroon’s political experience is not unusual regarding the electoral autocracies of sub-Saharan Africa. The president of Cameroon, Paul Biya, came to power in 1982. Before his succession, Cameroon held single-party elections regularly since independence in 1960 under its first president, Ahamdou Ahidjo. Although Cameroon lacked much of the instability that other African countries faced during the 1970s and 1980s—such as in Togo or Sudan—it is the poster child for “big man rule” in Africa. Since the turn to multipartyism in the 1990s, the ruling party has relied on a number of tactics to remain in power, such as altering the constitution in order to concentrate power in the hands of the executive branch, relying on gerrymandering to win artificially high numbers of legislative seats, and using various tactics to repress, delegitimize and split the opposition (Albaugh Reference Albaugh2011, 2014, chap. 6; Schedler Reference Schedler2002a).

Table 2 presents a history of multiparty elections in Cameroon, providing information about turnout and vote share for each election. Legislative and municipal elections are held separately in Cameroon, with legislative terms lasting five years and presidential terms lasting seven. Cameroon’s legislative districts work on a mixed system, with some multimember districts that elect party lists (51 districts representing 146 seats) and some single-member plurality districts (34 districts).

Table 2 Elections in Cameroon

* Opposition boycott

As can be seen from table 2, turnout in Cameroon is generally average amongst cases of electoral authoritarianism.Footnote 15 While average turnout across all electoral autocracies is about 67%, for Cameroon, turnout was 68.3% in the 2011 presidential election, 76.8% in the 2013 parliamentary and municipal election, and 53.9% in the most recent 2018 presidential election. Participation was exceptionally low for the most recent election because of the escalating violence in the anglophone regions.

I focus empirically on the 2013 parliamentary election in Cameroon because it was the most proximate election during the period of data collection. However, it is important to note that the theory presented here should be applicable to both presidential and legislative elections. In theory, we might expect expressive voting to be more common in presidential elections because these types of contests tend to be less competitive. Though a ruling party in an electoral autocracy will not lose its majority in parliament via elections, specific constituencies will feature competitive elections. In these locally competitive elections, vote-buying might be more common since campaigns are more decentralized. Also, existing work frequently argues that patronage voting is paramount to parliamentary elections because individuals with clientelistic relationships to a candidate expect patronage after the candidate wins the election (Lust Reference Lust2009; Miguel, Jamal, and Tessler Reference Miguel, Jamal and Tessler2015; Shehata Reference Shehata, Lust-Okar and Zerhouni2008). Thus, using data from a parliamentary election may be a “hard test” of the theory. Nonetheless, I do not argue that people never vote for economic reasons. If we see expressive voting in parliamentary elections, it may be safe to assume that we should also see such voting in presidential elections.

Economic Reasons for Participation

As Gandhi and Lust-Okar have noted, the scholarship on elections in autocracies “has focused on exploring the relationships between elections and democratization … [and] these tendencies have kept political scientists from asking a wide range of questions about the micro-level dynamics of authoritarian elections”(2009, 404). Indeed, the vast majority of the foundational studies on electoral autocracies have concentrated on the macro-level implications of holding elections, such as why dictators would hold them in the first place (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2011; Svolik Reference Svolik2012), how elections can stabilize autocratic regimes (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006; Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2006; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Wright Reference Wright2008), or, on the other hand, lead to democratization, at least under certain conditions (Donno Reference Donno2013; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2006; Schedler Reference Schedler2002b; Wolchik and Bunce Reference Wolchik and Bunce2006). While this scholarship provides an indispensable framework for understanding the macro-level implications of autocratic elections, very little work models or measures micro-level political behavior or preferences.

The most influential work that does exist largely relies on macro-level data in order to argue that citizens vote for economic reasons. For example, Magaloni’s (Reference Magaloni2006) analysis of Mexico under the PRI shows that the regime spent more money in PRI-controlled municipalities that were considered “swing districts” than it spent in heavily-controlled PRI districts or in opposition strongholds, suggesting that the government used such spending to encourage people to vote for them in elections. Blaydes (Reference Blaydes2011) goes as far as to state that “the majority of voters in Egypt make their voting decision based on clientelistic considerations” (101), similarly showing that electoral districts with higher vote shares for the opposition received fewer water and sewer improvement projects. She also argues that citizens were motivated to vote during elections due to vote-buying by showing that districts with higher levels of illiterate citizens also had higher levels of voter turnout. While this body of work systematically demonstrates that the state is spending in a way that correlates with voting behavior in electoral autocracies, due to the limitations of macro-level data, they cannot show whether or not individuals are affected by this logic of spending.

Only a handful of studies have used survey data to better understand voting in electoral autocracies. For example, analyzing a survey of the employees of firms in the regional capitals of Russia, Frye, Reuter, and Szakonyi (Reference Frye, Reuter and Szakonyi2014) find that 25% of workers were mobilized to vote by their employers. Miguel, Jamal, and Tessler (Reference Miguel, Jamal and Tessler2015) analyze Arabarometer survey data and find that citizens vote in autocratic elections not just because they expect a gift during the election, or increased spending afterwards, but also based on sociotropic voting; rewarding the regime with their vote when the economic climate is favorable and abstaining when the economy is doing poorly. This form of economic voting is the closest the literature gets to explaining turnout without relying on the argument that a voter will actually receive a material reward. However, it still presents a puzzle for understanding turnout in countries with terrible economic records, such as Togo, which saw negative economic growth numbers from 1998–2005. Magaloni and Greene also theorize about economic performance voting in Mexico under the PRI, but, still, neither of their models can explain the long-term economic stagnation that has occurred in many of Africa’s electoral autocracies.Footnote 16

I build on these micro-level approaches, but am able to investigate expressive reasons for voting by using original survey data that actually asks respondents why they vote in elections. Existing studies, especially from Magaloni and Greene, do argue that ideological voting exists in electoral autocracies, but they contend that it is isolated to opposition supporters—a small minority of voters in such regimes. Similarly, Croke, et al. (2016) make an argument about why more-educated citizens abstain from autocratic elections, but do not explain why people do participate. By exploring expressive reasons for participation, I argue that non-economic voting is not unique to opposition voters.

In addition to economic motivations for voting, another factor to consider is violence and intimidation. While electoral violence seems like a bread-and-butter issue of electoral autocracies, it has not actually been systematically studied within the context of these types of regimes.Footnote 17 Many stable, long-term electoral autocracies, such as Malaysia, Tanzania, or Cameroon, actually tend to feature relatively little electoral violence, at least after they have transitioned from closed autocracies. Electoral violence appears to be more common in more competitive or transitioning regimes, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, or Kenya (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2015). However, there are important exceptions, such as Zimbabwe or Ethiopia. I control for intimidation in the empirical analysis, but because it was so rare in Cameroon at the time of data collection (3.5% of survey respondents reported being threatened during the previous election),Footnote 18 it does not feature prominently in the analysis. In cases where violence and intimidation are more common (as in countries where economic motivations are more credible), we should expect the relative importance of expressive voting to diminish. Where violence is present, expressive benefits of voting must be extremely high for a citizen to risk participation. For example, voter turnout in the 2018 presidential election in Cameroon was just 5% in the Northwest region largely because there was so much fear of violence.

Finally, ethnicity is also an important component to understanding electoral behavior in sub-Saharan Africa (Eifert, Miguel, and Posner Reference Eifert, Miguel and Posner2010; Posner Reference Posner2005). However, ethnicity usually acts as a heuristic for other—usually instrumental—reasons for voting. By and large the literature argues that citizens are mobilized to vote by their local (ethnic) leaders because they are engaged in clientelistic networks; citizens depend financially on local patrons or chiefs, who mobilize them to vote for their preferred candidate during elections. Alternatively, recent work has shown that these relationships may not be coercive, but instead groups may vote with their chief because they trust his opinion and expect him to cooperate better with his preferred candidate in order to deliver resources to the community (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2013; Koter Reference Koter2013). Either way, while ethnic mobilization is likely captured in economic models of voting, I also include measure of ethnicity itself in the empirical analysis that follows.

Expressive Reasons for Participation

If most citizens do not receive or expect to receive an economic reward for voting, and electoral violence is not common, what accounts for the decision to participate in autocratic elections? Scholarship from democratic regimes has found that expressive reasons for voting are the most powerful explanations of electoral behavior. This work has focused on two forms of expressive voting: a sense of civic duty (Blais, Young, and Lapp Reference Blais, Young and Lapp2000; Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968) and the expression of partisanship (Brennan and Buchanan Reference Brennan and Buchanan1984; Hamlin and Jennings Reference Hamlin and Jennings2011; Schuessler Reference Schuessler2000). In their foundational study, Riker and Ordeshook (Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968) argue that rational explanations for voting, which focus on the costs and benefits of the voting act in relation to the competitiveness of the race, do not explain turnout as well as expressive reasons (what they call consumption benefits) for participation—particularly civic duty. In contrast to the benefits of voting related to your favored candidate winning the race, consumption benefits are derived from the act of voting itself, regardless of which party or candidate wins. Expanding on this idea of the intrinsic value of the voting act, Brennan and Buchanan (Reference Brennan and Buchanan1984) liken voters to fans “cheering” at a sports match: of course these fans hope their team will win, but regardless of the outcome, they will turn out to cheer at every match for the pleasure of cheering itself. Partisanship can be instrumental, but the authors argue that it can also explain voter turnout through its expressive properties.

My core argument is that citizens in autocratic regimes should also vote for expressive reasons, including a sense of civic duty and a desire to improve the level of democracy. The literature on authoritarianism has largely overlooked these motivations because they have essentially argued that the paradox of voting does not exist in autocratic elections: it is rational to vote because you expect an economic reward for doing so, whether that be an actual gift at the polling station, the expectation of an individual or collective reward after the election, or simply the promise of continued economic growth. However, I argue that even if economic rewards are present, it is unclear why expressive motivations would be entirely absent. Further, where bribes are not available, these expressive motivations may be just as important in autocratic contexts as they are in democratic regimes.

First, similar to democracies, citizens who feel that voting is a civic duty should be more likely to participate in elections. Although it may seem surprising that citizens of autocracies would feel a sense of civic duty, in fact, it might be even more common in such regimes because of the conflation between the ruling party and the state, as well as the state’s near-monopoly on political communications. Because of the blurring between party and state, voting for the ruling party can be seen as an act of patriotism and duty. For example, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) in Mexico—which ruled uninterrupted for 70 years—uses the colors of the Mexican flag as its symbol. Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) in Tanzania relies heavily on the historical symbolism of the state’s founding father, Julius Nyerere, to legitimize its hold on power since the country’s independence in 1961. Further, the legitimating rhetoric of electoral autocratic regimes oftentimes revolves around crediting the party with the state’s history of peace (Letsa Reference Letsa2017b). Ruling parties frequently point to peer countries or neighbors that face civil war or crisis, crediting the unity of the ruling party with the regime’s relative stability.Footnote 19 Electoral autocracies also use political crises to bolster their claims to patriotism and nationalism. For example, Putin has used his annexation of Crimea to appeal to Russian patriotism, crediting himself and United Russia for rebuilding popular pride in the Russian state.

These messages of patriotism are enabled by the regime’s stranglehold on the media and political communications (Lawson Reference Lawson2002). For example, the state often teaches through public school curricula and voter registration campaigns that voting is a duty. As Geddes and Zaller (Reference Geddes and Zaller1989) find in authoritarian-era Brazil, citizens with the strongest levels of support for the autocratic regime are those who receive messages from the state, but are not inclined to criticize or question these messages. Thus, while highly educated citizens might reject these messages of civic duty taught by the state (Croke, et al. Reference Croke, Grossman, Larreguy and Marshall2016), citizens with median levels of education—the plurality of citizens—would be more likely to accept them. Further, where the opposition is strong, such as in democratic regimes, challengers would be able to counter these narratives. In autocracies, where the opposition is structurally weak and lacks access to a free media, these messages of voting as patriotic act or a civic duty often go unchallenged (Letsa Reference Letsa2017a).

In addition, it may seem that a sense of civic duty should be weaker in autocratic regimes because historically civic duty has been conceptually tied to the pride of participating in democratic elections. However, for ordinary citizens, perceptions of democracy can be deeply subjective, and autocratic regimes do everything in their power to convince their citizens that elections are free and fair. Of the electoral autocracies surveyed by the Afrobarometer for Round 5 (Burundi, Cameroon, Mozambique, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda and Zimbabwe), only 15.4% of all respondents said that their country was “not a democracy,” compared to 18.0% who said their country was a “full democracy.”Footnote 20 The majority of respondents fall somewhere in between: 35.8% believe that they live in a democracy that has “minor problems,” while 30.9% say they live in a democracy that has “major problems” (Afrobarometer, Round 6). Although these figures are merely suggestive (as few surveys outside of the United States ask about civic duty), if half of citizens in electoral autocracies believe that they live in a democracy (whether a full democracy or one with minor problems), then it is conceivable that they also link the act of voting to a civic duty.

In Cameroon, it was clear from open-ended interviews with respondents that many types of people from many different backgrounds felt genuinely that voting was their duty. While supporters of the ruling party were, on average, more likely to see voting as a duty, an overwhelming number of opposition supporters and citizens who thought the whole system was rigged still saw voting as their duty. For example, when asked why the RDPC always wins elections, about 39% of respondents replied that they win because the elections are rigged. Of this 39% of respondents who said the elections are rigged, 57% still strongly believed that voting was a civic duty. Of course, not everyone who sees voting as a duty still votes in every election. But it is important to note that this belief is widespread amongst a diverse group of citizens, and I argue that citizens who do see voting as a duty should be more likely to vote than those who do not.

In addition to voting out of a sense of civic duty, I also argue that many citizens vote because they want to express their support for democracy. They believe that even if the election will not produce change, the act of voting improves the system as a whole. Unlike in single-party autocracies, citizens in electoral autocracies can choose to vote for the opposition or cast a null ballot. While few citizens would expect such a vote to result in a change in power, they may feel that such an act works as a symbolic vote for democracy (Hermet, Rose, and Rouquié Reference Hermet, Rose and Rouquié1978). Even some regime supporters believe that there is room for improvement, and hope that mass participation can strengthen the quality of elections. People who see the act of voting as meaningful for democracy should be more likely to vote than citizens who see participation as pointless, or worse—legitimating an autocratic electoral system. Thus, in addition to a sense of civic duty, voting may also act as an expression of support for democracy.

Citizens who have access to opposition narratives—either because they possess more education (Croke et al. Reference Croke, Grossman, Larreguy and Marshall2016), they have higher levels of socioeconomic status and therefore can access alternative sources of information such as the internet, or because they live in opposition strongholds (Letsa Reference Letsa2017b, Reference Letsa2017a)—may be more inclined to see their vote as an expression of their support for democratic reform. For these citizens, we might consider the act of voting an act of symbolic protest. Whereas the citizen who votes out of duty expresses her national identity as patriot, the citizen who votes out of protest expresses her identity as democrat. Though most citizens support democracy as a valence issue (Bleck and van de Walle Reference Bleck and van de Walle2013), not all of them should think of the relationship between voting and democratization in the same way. Those who think of the state as democratic anyways may be less likely to think that voting is important for its ability to democratize the system. Others may think of democratization as important, but may not see a link between the voting act and democracy. Such citizens see the act of voting as pointless, and opt out of elections entirely. I argue that the citizens in electoral autocracies who see their vote as a way to improve democracy should be more likely to participate in elections than those who do not see the relationship between democracy and voting.

A Micro-Level Analysis of Voter Opinions: Survey Data

In order to probe the plausibility of expressive voting in autocracies, the following section explores data from an original public-opinion survey conducted in Cameroon in 2014–2015, providing evidence for this theory of non-economic voting. It is important to note that while public-opinion data can provide support for the theoretical framework of voting here, the data is not an outright test of the causal effect of expressive voting. The empirical strategy of this paper is innovative because it is the first to directly ask ordinary citizens in autocracies why they vote and to specifically inquire about beliefs about expressive voting. To my knowledge, it is also the first to directly ask citizens about the relationship between voting and government spending. Thus, the goal of the data is to establish the existence and importance of expressive voting relative to the power of economic voting in autocracies.

However, the empirical tests cannot outright determine the causal direction of expressive motivations for voting and the act of voting itself. While a sense of civic duty is learned primarily from state communications, such as public school curricula, voter registration drives, and election campaigns, as well as from the family, community, church, or mosque, it is also likely that the act of voting itself solidifies these beliefs. Though, arguably it is unlikely that the act of voting creates a sense of civic duty; for someone who already believes that voting is a duty, the more one votes, the more likely they are to internalize that belief. Existing work from the United States and Canada argues that these values are learned early in life, finding that they correlate with things like religiosity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Arguably, believing that voting can improve democracy should be similar to believing that voting is a duty, though it is perhaps less likely to be fostered by the act of voting itself. The more one votes while noting that democracy is not improving, theoretically at least, the less likely one should feel that voting can improve democracy. As noted earlier, however, many citizens may indeed believe that democracy is improving if they think the elections are relatively free and fair. Regardless, the study cannot disentangle the causal direction of expressive motivations for voting and the act of voting itself. However, holding the belief that voting is a duty or can improve democracy is almost certainly prior to the first voting act; though these beliefs may deepen or weaken with more exposure to voting.

With this in mind, I use data from an original 85-question public-opinion survey that was administered in seven of Cameroon’s ten regions in English and French.Footnote 21 Seventeen public-opinion questions were borrowed from the Afrobarometer instrument in order to test reliability across instruments and sampling designs. A comparison of responses is provided in online appendix A, revealing that results are quite similar, even with the exclusion of the three northern regions. Within the seven sampled regions, the survey included 15 electoral districts sampled on two significant characteristics: 1) whether the department was urban or rural (with a fifty/fifty distribution), and 2) whether the department was an opposition area, an RDPC area, or an area that “swings” between the two.Footnote 22 The full sampling schedule of all electoral départements and arrondissements is included in online appendix B. Post-stratification weights were created to compensate for over-sampling in opposition and swing areas, as well as to readjust urban/rural sampling within these district types to match the national distribution.Footnote 23 In each enumeration area, I administered the survey with five research assistants, to willing and informed respondents aged 23 years or older,Footnote 24 and reached a total of 2,399 respondents. More details on the sampling procedure and descriptive statistics for the sample can be found in online appendix B.

Although in many ways, social sensitivity bias in survey response is unavoidable (Tourangeau and Yan Reference Tourangeau and Yan2007), certain steps were taken to improve the reliability of response rates and measurement. First, Cameroon was specifically chosen as the site of fieldwork because political repression at the time was rare amongst ordinary citizens, and therefore relative to some autocratic contexts, the fear of retribution for participation in the survey was low. Second, a 100-respondent pre-test of the instrument was conducted in Yaoundé prior to full implementation. A number of questions and question orderings were altered to improve comprehension and minimize response bias. Third, measurement of the key dependent and independent variables were carefully designed to minimize social sensitivity bias.Footnote 25 For example, it has been shown that people over-report voting behavior in surveys (Tittle and Hill Reference Tittle and Hill.1967), and so the survey took steps to minimize this bias by providing respondents a list of options regarding the previous election.Footnote 26 Further, as an alternative measure of the potentially sensitive question of patronage voting, the regression analysis includes unbiased measures of local government investments, and dummies for the interviewer were included as controls. Online appendix C fully explains the steps taken to address social sensitivity bias.

Dependent Variable

The primary goal of the following analysis is to determine why citizens vote in autocratic elections. Thus, the dependent variable of the following regression analyses is a dichotomous measure of whether or not the respondent reported voting in the most recent 2013 legislative and municipal elections. As a robustness check, online appendix D runs the main models on whether or not the respondent reported voting in the most recent 2011 presidential election, finding similar results. While few Cameroonians expect the opposition to win elections, national elections are still an important event in the country. Overall, 70.1% of Cameroonians reported voting in the 2013 legislative and municipal elections (compared to the official figure of 76.8% of registered voters). Because the dependent variable is a dichotomous measure of past voting behavior, all analyses use logit models.

Independent Variables

In order to explain variation in reported voting behavior, the analysis includes five different survey questions (as well as one non-survey measure) specifically designed to probe the potential reasons a respondent might have to vote in elections. The first four measures are explanations provided by the existing literature, and account for vote-buying, expectations of local government spending, actual district-level government spending, and the respondent’s evaluation of the national economy. The second set of measures account for the proposed non-economic motivations: civic duty and a desire to improve democracy.

The first economic question measures vote-buying by asking the respondent whether or not they received money or a favor from a candidate or party during the previous election. Despite some concerns about social sensitivity bias, 10.9% of all respondents reported receiving a gift during the previous election. Of the respondents who reported receiving something, 89% said they received the money or gift from the ruling party.

In addition to vote-buying, the analysis presents two different measures of the concept of “electoral patronage.” The first, designed to improve on the existing approach of measuring aggregated spending, is a direct measure of expectations of patronage. The survey asked respondents: “In your opinion, do you think that if voter turnout is high in your district, the government will reward the district with resources like schools, health clinics or paved roads?” Overall, 53% agreed, 40% disagreed, and 7% didn’t know. To my knowledge, this is the first survey to ask respondents directly about their beliefs regarding the logic of electoral patronage.

The second measure, state spending, was constructed from government investment budgets collected by the author from Cameroon’s Ministry of Economy, Planning, and Regional Development (MINEPAT) for 2008–2015. Investment budgets cover many different types of projects depending on the ministry, such as the building of classrooms (Ministry of Secondary Education), irrigation channels (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development), roads projects (Ministry of Public Works), or even public rest stops (Ministry of Tourism and Leisure). These budgets do not include operations costs, such as salaries or monthly bills (electricity, etc.). While this measure may appear broad, its advantage is its ability to capture most potential sources of electoral patronage (Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2013). The measure is constructed at the level of the département in which the respondent was interviewed, which corresponds with electoral districts. Since the government uses spending as a way to incentivize voter turnout, the literature would predict that citizens living in areas with higher levels of investment should be more likely to vote in elections.

Finally, in order to measure whether citizens are voting primarily because they approve of the economic performance of the government, I include a question designed to capture the respondent’s evaluation of economic performance. This is a standard question following Miguel, Jamal, and Tessler (Reference Miguel, Jamal and Tessler2015): “In general, would you describe the present economic condition of Cameroon as good, bad, or neither good nor bad?” Overall, Cameroonians hold a rather bleak view of the economy. Forty-five percent say the present economic condition is either “fairly bad” or “very bad” compared to only 16% who say it is “fairly good” or “very good.” The survey also included questions about the respondent’s evaluation of the economy over the past year, as well as egotropic questions about the respondent’s own present economic situation as well as their situation over the past year. Results are robust to these alternative specifications.

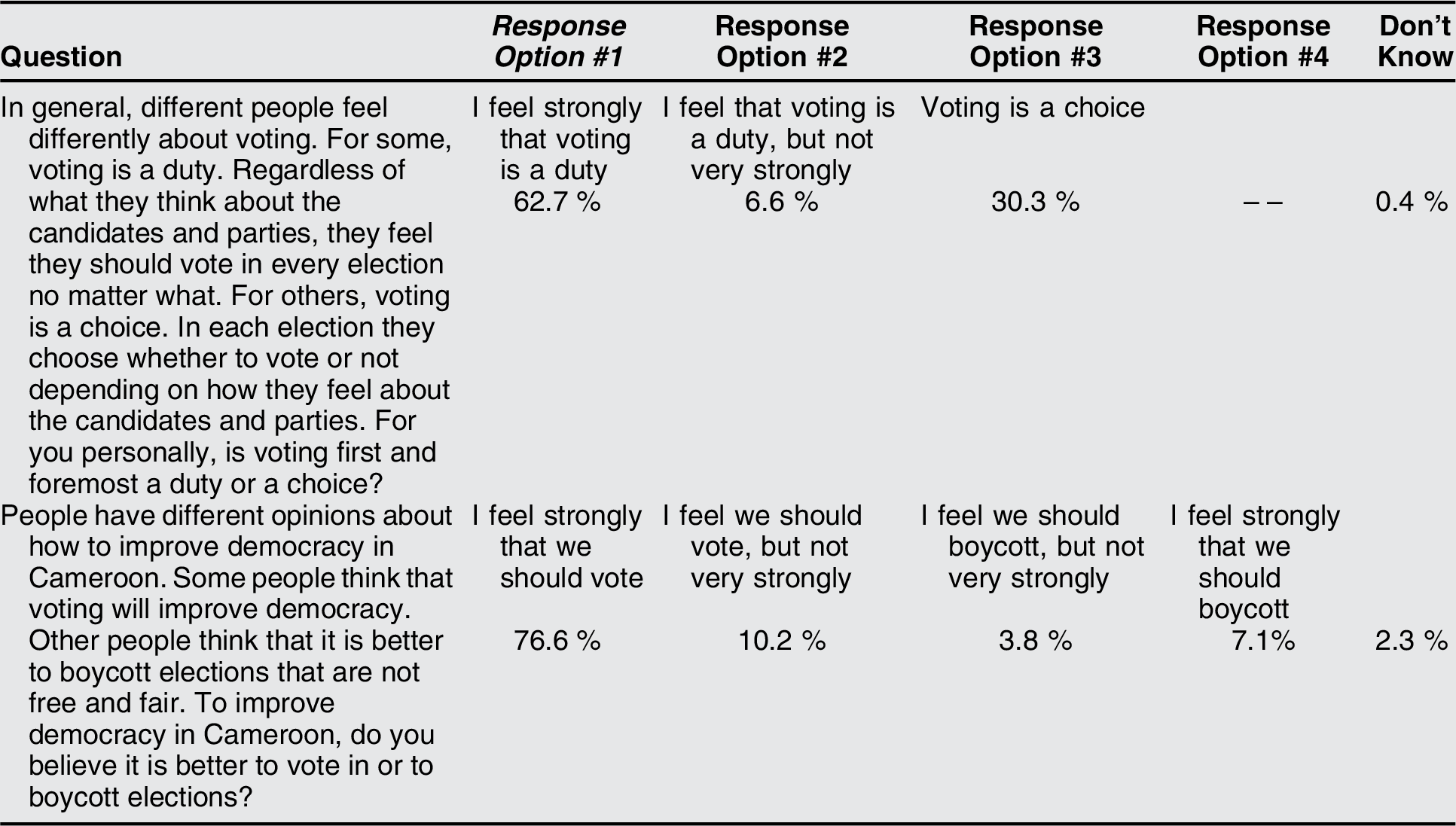

In addition to these four measures of economic motivations, I also include two questions that measure the proposed non-economic reasons for voting. The full question wordings are presented in table 3. The questions were specifically designed to avoid acquiescence bias. In order to do this, the first question about civic duty provides the respondent with two compelling logics for voting being either a choice (“un choix”) or a duty (“un devoir”) (Reference Blais and AchenBlais and Achen n.d.). It then asks with which one they agree. Despite the autocratic nature of elections in Cameroon, fully 69% of respondents believe that voting is a duty. Similarly, the next question offers respondents two options regarding the democratic aspects of voting, asking whether the best way to improve democracy is to abstain from an unfair process as a form of boycott,Footnote 27 or to vote to increase representative participation. Nearly 87% of respondents believe that voting is the best way to improve democracy—relatively few Cameroonians believe that boycotting elections can improve democracy.

Table 3 Question wording and responses

Overall, the response figures indicate that, in general, Cameroonians are familiar with these different logics of voting. For example, although, a priori, it may seem doubtful that citizens of an autocratic regime think of voting as a civic duty, it is clear that a robust majority believe that it is. Further, Cameroonians who did not believe voting was a duty still understood the concept: only 0.4 percent of all respondents reported that they did not know if voting was a duty or a choice. Similarly, only 2.3 percent of respondents did not know or did not have an opinion about whether it was best to vote or to boycott elections.

Control Variables

Full models include demographic and structural variables to control for the effects of socioeconomic status and other factors on voting. Online appendix E presents the coefficients and standard errors of these control variables from the models in table 4. First is an index of personal wealth borrowed from the Afrobarometer, measured by an additive list of items the respondent reported owning. As a robustness check, online appendix F interacts this measure with the economic reasons for voting. The models also include the respondent’s gender, age, education, and locality (urban or rural). Descriptive statistics of these measures within the entire sample can be found in online appendix B. I also include the respondent’s ethnicity. I received more than 200 different responses to the question, “To which ethnic group do you belong?”, and so I therefore include only the top ten ethnic groups represented in the survey: all groups that had 50 or more respondents, plus a category for “other”. This includes the Beti, Douala, Makas, Bamiléké, Bamoun, Bassa, Bayangi, Kom, Mamfe, and Moghamo. Taken together, the top ten ethnic groups account for 66.5% of the sample.

In order to control for voter intimidation, I include a question that asks the respondent whether or not during the last election “any candidate or party activist threatened you in any way” as well as a measure of how free the respondent feels one is “to choose whom to vote for without feeling pressured.” Within the sample, 92.5% of respondents reported that they felt Cameroonians were somewhat or completely free to vote for whomever they wanted. To control for political information, I include a variable that measures how much news the respondent consumes. In addition, a measure of vote share for the ruling party in the 2011 presidential elections is included at the electoral district level in order to approximate the competitiveness of the district. Studies have found that turnout is higher in more competitive elections (Downs Reference Downs1957; Geys Reference Geys2006; Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968).

Finally, because differences in vote choice might affect why different people would choose to participate in elections, I also include a dummy for the respondent’s partisanship, which includes three options. A ruling-party partisan is a respondent who reports feeling close to the RDPC (26.3% of the sample). An opposition-party partisan is a respondent who reports feeling close to any one of Cameroon’s opposition parties (9.45 of the sample). The omitted category is nonpartisans. To further investigate if vote choice is driving the results of the turnout model, online appendix G reports the results of the main regression results with partisanship interacted with each of the six primary independent variables. All statistical analyses include post-stratification survey weights, as well as region dummies and interviewer dummies. Standard errors are clustered at the enumeration area, which is the lowest level sampling unit.

Results

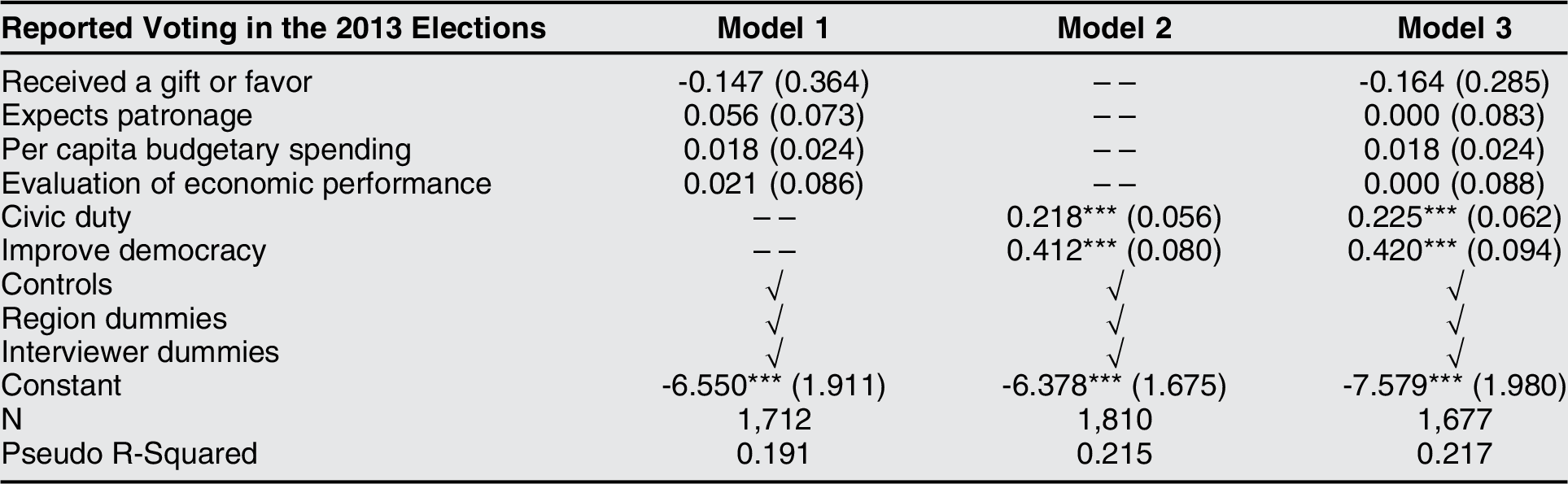

The first set of analyses, presented in table 4, execute various model specifications in order to investigate the relative explanatory power of the three economic versus the three non-economic measures. Model 1 assesses just the economic motivations, including all control variables. Results reveal little evidence for a robust relationship between any of the economic motivations for voting and self-reported voting behavior. All four economic measures are statistically insignificant, and the sign for vote-buying is actually negative. In all, it is difficult to conclude from Model 1 that economic motivations for voting strongly predict voting behavior.

Table 4 Motivations for voting in Cameroon

Notes: Coefficients are reported. Standard errors are given in parentheses. Standard errors clustered at the sampling unit.

*p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***0.01

Model 2 investigates the non-economic reasons for voting, including the same set of control variables. Unlike the economic motivations, the expressive reasons for voting have a positive and statistically robust relationship to reported voting behavior. Finally, Model 3 includes all six measures of voting motivations, along with the set of controls. In general, the findings from Models 1 and 2 are replicated: the two expressive motivations for voting remain positive and statistically significant, while the economic measures remain statistically insignificant. In fact, including the economic measures of voting actually increases the values of the coefficients on the expressive motivations.

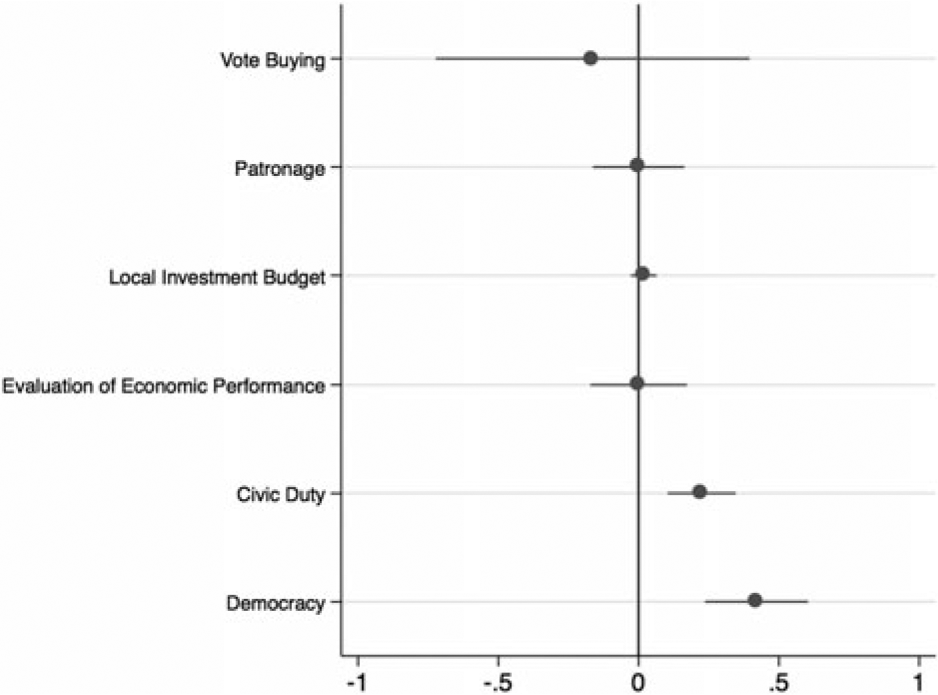

In order to better interpret these results, figure 1 presents the findings for the six variables of interest of Model 3 graphically in a coefficient plot. The plot helps to visualize the relative magnitude of the voting motivations. Notably, the confidence intervals on vote-buying are quite large. In Cameroon, traditional vote-buying—the monitored exchange of money or goods for a vote—is not common because the RDPC does not operate as a political machine; it is likely that the majority of respondents who reported having received something in the previous election were describing having received something at a political rally. Such rallies are extremely common in African elections, and political parties tend to hand out small gifts, such as soap, rice, or t-shirts. However, these gifts are not usually considered reciprocal, as the exchanges are informal and unmonitored. It is not unusual for someone to go to the campaign rallies of different parties, collect small gifts at each, and then refrain from voting altogether. This likely explains the wide confidence intervals on the measure of electoral gifts: while a substantial minority of citizens may have received something during the previous election, the gift does not predict behavior. For belief in electoral patronage, per capita government spending, and the respondent’s evaluation of the national economy, the coefficients are effectively zero.

Figure 1 Coefficient plot of Model 5

Overall, a respondent who said they received a gift or favor in the previous election was not any more or less likely to say they voted than a respondent who said they did not receive a gift or favor. A respondent who believes that if voter turnout is high their district will be rewarded is not more likely to report having voted than a respondent who does not believe in the relationship between voting and government spending. Citizens living in districts with high government spending (the maximum value is 39 CFAs per capita in Ebolowa in the president’s home region) do not report voting at higher levels than citizens in districts with low levels of spending (the minimum value is 4 CFAs per capita in Fundong in the Northwest Region). Finally, a respondent who believes that the present economic condition of Cameroon is very good is no more or less likely to have reported voting than someone who believes the economy is very bad.

In contrast, the expressive reasons for voting do correlate with voting behavior. Citizens who believe voting is a duty are nearly seven percentage points more likely to vote than their peers who view voting as a choice. Even more conspicuously, citizens who strongly believe voting can improve the quality of democracy in Cameroon are 21% more likely to vote than those who believe strongly that it is better to boycott elections that are not free and fair. Particularly in comparison to economic reasons for voting, the data makes clear that expressive motivations are an important part of understanding the voting act in electoral autocracies.

Discussion and Implications

Overall, these findings regarding non-economic motivations for voting add complexity to the traditional assumptions of electoral behavior in autocratic regimes. The data casts doubt on the argument that citizens in autocracies only vote in order to receive a material reward, whether through vote buying or patronage. The logic of electoral patronage certainly exists in Cameroon, but after 25 years of multiparty elections and continued economic stagnation and underdevelopment, many citizens doubt the connection between electoral returns and the provision of public goods. Instead, citizens hold more ideational reasons for voting. For example, many citizens in autocratic countries possess a high level of patriotism (nurtured by the regime itself), and feel pride in fulfilling their civic duty come election day. As one female RDPC supporter told me in Foumban, “I vote the RDPC because it’s the ruling party. I grew up with it. My mother was a member since I was a child.”Footnote 28 Other citizens hope that their participation may have some symbolic effect on the level of democracy. As one teacher noted, “I support the opposition for change. Everyone says we should support the RDPC because things are ok or they will make things better, but I don’t agree.”Footnote 29 Such citizens are aware that their vote will not significantly alter the balance of power in government, but are still committed to voting because they believe that their participation can make a larger systemic difference, even if it is only symbolic.

Given the unique under-development of the electoral autocracies of sub-Saharan Africa, can the theory developed in this article be applied outside of Africa? In part, this is an unanswered question. However, the likely answer is that some percentage of citizens of all electoral autocracies vote for expressive reasons, but the proportion of citizens who do so depends on the credibility of the state’s economic incentives and repressive behavior. Although a weak state is not a scope condition of the theory presented in this article, the importance of non-economic voting is likely inversely related to economic development: As economic rewards for voting become less credible (and violence less common), the proportion of citizens voting for non-economic reasons should increase.

I have demonstrated that in Cameroon, the proportion of citizens who vote for economic reasons appears smaller than the literature would suggest. While the existing literature has argued that in places like Mexico under the PRI and Egypt under the Mubarak regime the vast majority of citizens vote for economic reasons, these studies have not taken into account the possibility of expressive reasons for voting. Even where economic incentives for voting are credible for larger proportions of the population, many citizens presumably vote for expressive reasons.

If citizens of electoral autocracies vote primarily for non-economic reasons, how do the implications of their behavior differ from a world in which citizens primarily have economic motivations for voting? The theory in this article implies three important differences in our broader expectations about autocratic politics. First, from a more micro-level perspective, expressive reasons for voting can shed light on the campaign strategies of parties, candidates, and elites, which provide us with a whole range of possibilities that we are blinded to if we focus solely on strategies of vote-buying, electoral patronage, and economic performance. Second, the significance of voter turnout takes on a different meaning and has different consequences if citizens vote primarily for expressive reasons. Third, and relatedly, many of our theories of autocratic regime stability rely on arguments about economic growth, which are predicated on the argument that citizens only support or tolerate the regime when they receive economic incentives and benefits for doing so. But if most citizens do not receive or expect to receive economic benefits from the state, then economic growth may not always be the cornerstone to explaining regime stability. Future research on political participation in autocratic regimes should take these motivations seriously. By relaxing the assumption that most citizens vote because they expect a material reward or because they approve of the economic performance of the regime, we can explain the longevity of some of the poorest and most under-performing electoral autocracies in the world, such as Cameroon. When states can develop legitimacy outside of clientelistic networks, they are able to endure decades of economic stagnation.

Supplemental Materials

Appendix A: Replicability of Survey Results (Comparison to Afrobarometer)

Appendix B: Survey Sample Details

Appendix C: Social Sensitivity Bias

Appendix D: Voted in the 2011 Presidential Election

Appendix E: Full Regression Results

Appendix F: Socioeconomic Status, Electoral Patronage and Voting

Appendix G: Partisanship and Voting

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719001002