Low-income Americans receive lower levels of political representation than other Americans (Butler Reference Butler2014; Miler Reference Miler2018). By some accounts, they receive no meaningful political representation at all (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012). This may be partly due to their vastly lower levels of political participation and leadership (Carnes Reference Carnes2013, 2018; Franko, Kelly, and Witko Reference Franko, Kelly and Witko2016; Hajnal and Trounstine Reference Hajnal and Trounstine2005; Hill and Leighley Reference Hill and Leighley1992; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). Arguably, no route to participation and influence is more effective than education (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Expanding educational opportunities for low-income people could thus be an effective means of addressing the problem of unequal representation.

However, with rising income inequality, the gap in college completion between rich and poor students has increased by about 50% since the late 1980s (Bailey and Dynarski Reference Bailey, Dynarski, Duncan and Murnane2011; Mettler Reference Mettler2014).Footnote 1 There are growing gaps between children from high- and low-income families in college entry, persistence, and graduation. For the poorest fifth, the cost of public universities has increased from 42% to 114% of family income, while only increasing from 6% to 9% for the top income group (Mettler Reference Mettler2014). In the 1970s, Pell grants covered 80% of the cost of a public university, but now they cover 31%. State governments have decreased their funding for higher education such that spending per full-time public student fell 26% between 1990 and 2010 (Mettler Reference Mettler2014). This has resulted in a significant increase in student debt, with particularly pernicious effects on lower-income students, who are likely to leave college with onerous loans and without a degree that facilitates paying them off (Goldrick-Rab Reference Goldrick-Rab2016; Mettler Reference Mettler2014).

These trends toward inequality in higher education are part of a general trend toward inequality in education overall. Higher-income parents increasingly pass advantages on to their children by investing more time and money in cultivating them and securing better quality schooling for them, while the children of those who start out behind are increasingly likely to remain behind (Lareau Reference Lareau2011; Putnam Reference Putnam2015; Reardon Reference Reardon, Duncan and Murnane2011). Hand in hand with the increasingly unequal investment in children, the academic achievement gap between high- and low-income students has increased: it is about 40% higher for those born in 2001 than those born 25 years earlier (Reardon Reference Reardon, Duncan and Murnane2011). That is due to income rather than race; in fact, the rich-poor gap now exceeds the white-black gap (Reardon Reference Reardon, Duncan and Murnane2011). This early-life gap then continues through to college application and completion. Lower-income high school students are less likely than higher-income students to attend four-year institutions mostly because they do not apply or have poorer academic preparation (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen, Kurzweil, Tobin and Pichler2005). Overall, then, education is reflecting broader trends toward inequality in American society (Haveman and Wilson Reference Havemann, Wilson, Dickert-Collin and Rubenstein2007).

By making college much more accessible to affluent than to lower-income families, income inequality has two consequences. First, it distributes access to a major pathway to political activity unequally. Second, it creates affluent social environments: the median four-year institution draws approximately half of its students from the top 25% of the income distribution.Footnote 2 That is, on many campuses, affluent students are the majority, rendering college an affluent social setting (Armstrong and Hamilton Reference Armstrong and Hamilton2013; Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Reference Stevens, Armstrong and Arum2008; Mendelberg, McCabe, and Thal Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017). These trends are eliciting a growing public debate about economic diversity in higher education (Anderson Reference Anderson2017; Chetty et al. Reference Chetty, Friedman, Saez, Turner and Yagan2017). In an era of low economic diversity in the educational institutions central to democracy, it is important to understand how affluent environments affect the low-income individuals who attend them. A central question for political science is whether these increasingly unequal environments play a role in the SES gap in political engagement, participation, and leadership.

We consider three opposing expectations. First, these campuses may narrow the SES engagement gap by raising the engagement of low-income students. Affluent Americans are much more likely to engage with politics (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012), and high concentrations of affluent individuals may create norms of engagement (Campbell Reference Campbell2006). Low-income students attending affluent campuses may adopt these norms, leading them to become more politically engaged. If predominantly affluent colleges help lower-income students to “catch-up,” then the effect on these students may be larger than on affluent students attending the same school. In that case, affluent colleges might narrow the SES gap in engagement. Because these are impressionable years, the effects likely last over a lifetime, muting inequalities of representation downstream (Sears and Funk Reference Sears and Funk1999).

On the other hand, affluent environments may instead reinforce participatory inequality (Kelly and Enns Reference Kelly and Enns2010; Solt Reference Solt2010). Affluent campuses may create psychological, academic, social, or financial difficulties for low-income students. Some of these difficulties may be worse than in campuses where lower-income students are not a distinct minority and where their needs are better recognized (Armstrong and Hamilton Reference Armstrong and Hamilton2013; Jack Reference Jack2014). These difficulties in turn may interfere with the development of political engagement (Armstrong and Hamilton Reference Armstrong and Hamilton2013). Campuses with many affluent students could thus enhance the income gap in political engagement. This finding would support theories arguing that institutions carry different effects for people with different participatory resources (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012).

Finally, the effect of affluent student bodies may instead be the same for all students. Low-income students may benefit from attending affluent campuses, but no more or less than other students do. Affluent campuses may ameliorate political disadvantage by engaging lower-income students better than non-affluent campuses do, but they may not be able to overcome the legacy of disadvantage enough to narrow the SES gap among their students.

In arbitrating between these competing hypotheses, we aim to contribute to the study of the effects of education on political engagement (Campbell Reference Campbell2009). In recent decades, “every significant indicator of political engagement has fallen by at least half” (Galston Reference Galston2001, 219), with the decline led by the young (Stoker and Bass Reference Stoker, Bass, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011). What higher education can do to elevate those low rates as adolescents enter adulthood is thus a central question that goes to the heart of democratic practice. We enter the debate not by comparing those with and without a college education, but in comparing different types of college settings. The question becomes what sorts of educational experiences reinforce class inequality, among the set of individuals who attend college (Campbell Reference Campbell2009).

Several studies have assessed the effects of college experiences (Astin Reference Astin1993; Dey Reference Dey1996; Hillygus Reference Hillygus2005; Sidanius et al. Reference Sidanius, Levin, Laar and Sears2008). However, these studies have not found a link between college experiences and political action (as we elaborate later). Nor do they focus on how political socialization differs by socio-economic class, or on the concentration of affluence. These questions about education and political participation flow directly from questions about rising income inequality and American democracy, yet they have not received much attention. Why lower-income individuals participate far less than others remains an under-explored question despite its importance to inequality (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012).

We examine these questions with a large two-wave panel of 201,011 students in 571 schools. The panel data cannot fully account for all confounders, nor for the well-known problem of selection bias. However, the data does allow us to improve on current attempts to deal with selection into educational settings, by accounting for the student’s pre-treatment starting point. To that end, we estimate the affluent campus effect separately at different levels of pre-college political engagement (following, for example, Nall Reference Nall2018). This self-selection test is a useful but missing feature in many studies of higher education and of context effects more generally. We also conduct additional tests using other subsets of students. Finally, we also control on a host of competing explanations. An additional strength of the data is that it allows us to examine an extensive array of psychological, academic, social, financial, institutional, and political mechanisms.

We find that low-income students emerge from predominantly affluent campuses moderately more politically engaged relative to their counterparts in non-affluent campuses, even when accounting for their starting points. However, for some outcomes, the effect depends on generous financial aid. In fact, concrete aid emerges as perhaps the most important mechanism, suggesting that this is the experience that matters for low-income students’ political engagement. However, on most forms of participation, low-income students benefit no more than their higher-income peers. These parallel effects mean that the SES gap fails to close. These findings contribute to the emerging literature on how institutions affect the social reproduction of unequal power (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004). Among these institutions are colleges, and their consequences derive partly from their concentration of affluence.

College Effects and Social Norms

Foundational studies of participation conclude that education is the biggest predictor of political participation (Highton and Wolfinger Reference Highton and Wolfinger2001; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). However, recent studies cast doubt on the causal impact of college (Berinsky and Lenz Reference Berinsky and Lenz2011; Kam and Palmer Reference Kam and Palmer2008; Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik-Barry1996; Henderson and Chatfield Reference Henderson and Chatfield2011). Even the specific experiences that education is thought to provide may not have a causal impact on participation. There is also no evidence of a causal effect of civics curricula, service learning, participation in student-led activities, volunteering, or democratic classroom climates on political action (Niemi and Junn Reference Niemi and Junn1998; Pascarella and Terenzini Reference Pascarella and Terenzini2005).

However, higher education may matter indirectly. Sociological studies emphasize the social nature of the college environment, where many “activities are explicitly social, oriented around forging, maintaining, and displaying bonds with peers” (Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Reference Stevens, Armstrong and Arum2008, 132). Because students are highly motivated to gain acceptance from their college community, college peers have well-documented effects on academic achievement, career decisions, alcohol consumption, study habits, joining organizations, and voting (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2008; Sacerdote Reference Sacerdote, Hanushek, Machin and Woessman2011). Beyond the dyadic effect of a roommate, the characteristics of the entire student body may also matter. Such characteristics have a bigger association with political attitudes and behaviors than other institutional features, including selectivity, size, private status, or vocational orientation (Pascarella and Terenzini Reference Pascarella and Terenzini2005). Because students are affected by their peer community, the community’s social characteristics may act as powerful agents of political socialization, often by creating norms (Campbell Reference Campbell2006).

One such social characteristic is the affluence of the student body. This variable creates norms that shape class-relevant attitudes, even after accounting for selection and other competing explanations (Mendelberg, McCabe, and Thal Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017). One question that follows from this finding is how predominantly affluent campuses affect political engagement, especially for those who come from lower-SES backgrounds and correspondingly lower levels of participatory resources. Do affluent social settings elevate lower-income students’ participation? Or do they instead depress participation, functioning as institutions that reproduce class inequality in politics?

Negative Effects of Campus Affluence on Low-Income Students

The negative expectation for campus affluence derives from theories of class that emphasize its cultural aspects (Lamont and Molnar Reference Lamont and Molnar2002). We focus on these theories because they offer clear and strong predictions about class environments. Bourdieu is perhaps the best known of these theorists (1984; Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1990). Class-culture theory has three elements. First, class generates deeply internalized class identities, behavioral scripts, and norms. In that sense, class is not merely a set of concrete resources, but also a type of culture. Second, class is a social rank. Groups with resources are assigned higher symbolic value, and their cultural practices become powerful social norms (Russell and Fiske Reference Russell and Fiske2008). Third, educational institutions aid the social reproduction of class across generations by assigning a higher value within the institution to upper-class norms (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1990; Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Reference Stevens, Armstrong and Arum2008, 133). They do so by admitting many high-income students and making possible the development of upper-class lifestyles within the institution (Armstrong and Hamilton Reference Armstrong and Hamilton2013). The institution thus creates a community where upper-class ways of life are the norm and carry prestige and esteem. Low-income students are valued less, institutionally and socially, and derive fewer gains from attending the institution (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005; Goldrick-Rab Reference Goldrick-Rab2016). These educational institutions cultivate the habits of mind and behaviors that correspond to upper-status roles, but these tend to be absorbed more by high- than low-status students (Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Reference Stevens, Armstrong and Arum2008).

Because participation is more prevalent among higher SES individuals, participation forms part of an upper-class cultural role (Nie et al. Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik-Barry1996). Lower-income students may not reap the same participatory benefits from education, because they are less well positioned within the status hierarchy of affluent campuses, and less able to absorb the participatory norms of the affluent majority (Giles and Dantico Reference Giles and Dantico1982; Huckfeldt Reference Huckfeldt1979). For example, the voting norms of a campus matter only when a student perceives a similarity to other students at the school (Glynn, Huge, and Lunney Reference Glynn, Huge and Lunney2009). Consequently, predominantly affluent colleges may foster political participation by individuals with higher-income backgrounds but inhibit the development of political engagement for those from low-income backgrounds. We call this the cultural mismatch hypothesis.

One mechanism through which cultural mismatch may negatively affect low-income students’ political participation is psychological injury (Sennet and Cobb Reference Sennet and Cobb1972). Lower-status people may perceive themselves as less empowered and less in control of their lives. This diminished sense of personal efficacy may lead to lower political efficacy and participation (Hillygus, Holbein, and Snell Reference Hillygus, Holbein and Snell2015; Kraus, Piff, and Keltner Reference Kraus, Piff and Keltner2011; Kraus, Rheinschmidt, and Piff Reference Kraus, Rheinschmidt, Piff, Fiske and Markus2012; Cohen, Vigoda, and Samorly Reference Cohen, Vigoda and Samorly2001). If students’ lower status is made salient in affluent campuses, as suggested by cultural mismatch theory, these “hidden injuries of class” may intensify (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005, 428; Johnson, Richeson, and Finkel Reference Johnson, Richeson and Finkel2011; Lamont and Molnar Reference Lamont and Molnar2002, 172; Stephens et al. Reference Stephens, Bannon, Markus and Nelson2015), decreasing political participation.

A second mechanism is academic struggle. Working-class people are stereotyped as less intellectually competent, and tend to arrive at college with less preparation, which may generate feelings of inadequacy (Charles et al. Reference Charles, Fischer, Mooney and Massey2009; DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio1982; Stephens et al. Reference Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson and Covarrubias2012). Academic difficulty may contribute to self-doubt especially in largely affluent campuses, where norms of affluence may condition low-income students to feel that they do not belong (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005; Johnson, Richeson, and Finkel Reference Johnson, Richeson and Finkel2011), inhibiting the development of their political engagement.

A third mechanism is social marginalization. As Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum put it, “having the ‘right’ clothes, body, hygiene practices, hair style, accent, cell phone, and musical tastes can matter” to one’s access to social networks on campus (2008, 133). Low-income students may have a mismatch between their experiences and those esteemed in upper-class environments (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005). The community’s affluence may create a lack of social fit, denying low-income students social ties that might facilitate political participation.

Fourth, affluent colleges may demobilize low-income students via stigmatizing institutional practices. For example, many low-income students must work on campus as part of their aid package. In largely affluent campuses, this means serving affluent peers in the cafeteria and other social spaces, which may make their relative status salient. As another example, low-income students tend to feel marginalized by the fact that dorms close during breaks, because they cannot afford to go home (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005). This may matter more in largely affluent campuses, where affluent students are untroubled by dorm closings. Such practices may catalyze cultural mismatch in affluent campuses, inhibiting low-income students’ political engagement.

These mechanisms of cultural mismatch may undermine the positive effect of the political norm of engagement that may exist on affluent campuses, a concept we elaborate in the next section. A cultural mismatch may mean that norms of political engagement have less influence on low-income students. For example, the voting norms of a campus matter only when a student perceives a similarity to other students at the school (Glynn, Huge, and Lunney Reference Glynn, Huge and Lunney2009). It follows that a cultural mismatch may interfere with the uptake of participatory norms. This prediction is reinforced by studies of adult affluent settings that show that these spaces promote the participation of affluent individuals only (Giles and Dantico Reference Giles and Dantico1982; Huckfeldt Reference Huckfeldt1979).

Aside from cultural mismatch, we also recognize—and test—the importance of concrete financial hardship. That is, class may matter not only psychologically and socially, but also materially. Low-income students often experience substantial hardship because aid is inadequate or they must work onerous hours (Goldrick-Rab Reference Goldrick-Rab2016). For example, at one predominantly-affluent school, one-quarter of students on full financial aid lacked money to buy food, and over half provided financial support to their families (Broton, Frank, and Goldrick-Rab Reference Broton, Frank and Goldrick-Rab2014, figure 2 and table 4). Low-income students tend to work a significant number of hours (Armstrong and Hamilton Reference Armstrong and Hamilton2013; Pascarella et al. Reference Pascarella, Pierson, Wolniak and Terenzini2004; Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Reference Stevens, Armstrong and Arum2008, 133). The resource model of political participation would predict that this lack of concrete resources lowers participation (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). If largely affluent schools create more financial difficulty, they may enhance the class gap in political participation.

In sum, campus affluence may negatively affect the participation of low-income students. Low-income students may experience psychological distress; academic struggle; a lack of social fit; or stigmatizing school practices. In addition, predominantly affluent schools may inhibit participation through a resource pathway, if they tend to impose a higher financial or workload burden. Concrete resources may matter, not just symbolic experiences.

Positive Effects of Campus Affluence on Low-Income Students

On the other hand, affluent campuses may not inhibit low-income political participation, and may even boost it, for two reasons.

First, the cultural mismatch hypothesis may simply be incorrect. Many low-income students in affluent schools seem to overcome initial social isolation and develop friendships with affluent students (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005, 432). Social isolation may thus be far lower than the mismatch hypothesis expects. In addition, when low-income individuals succeed despite the obstacles, their internal efficacy increases (Soss Reference Soss1999). Many low-income students overcome their challenges, often with a narrative of resilience that draws on positive aspects of their class identity, and many develop higher self-confidence as their academic performance improves (Aries and Seider Reference Aries and Seider2005, 419; Charles et al. Reference Charles, Fischer, Mooney and Massey2009; Crocker and Major Reference Crocker and Major1989). Resilience in turn is associated with higher political engagement (Hillygus, Holbein, and Snell Reference Hillygus, Holbein and Snell2015). These positive reports seem to be particular to affluent schools.Footnote 3 Predominantly affluent schools may thus make one’s working-class identity more salient in positive ways, resulting in positive effects on political engagement.

Second, if cultural mismatch is not a barrier, low-income students on affluent campuses may absorb the stronger norm of political participation that is likely present on affluent campuses. This constitutes a political mechanism for positive campus-affluence effects. The higher one’s SES, the more politically engaged one is (Hill and Leighley Reference Hill and Leighley1992; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Walsh, Stoker, and Jennings Reference Walsh, Stoker and Jennings2004; Hill and Leighley Reference Hill and Leighley1992). Places with many affluent individuals tend to produce more participatory social norms (Huckfeldt Reference Huckfeldt1979; Giles and Dantico Reference Giles and Dantico1982). These places may offer more opportunities for academic or extra-curricular activities that promote civic engagement or political awareness. Thus, campuses with more affluent peers may produce a norm of political engagement. On average, students accurately perceive campus norms of political participation (Shulman and Levine Reference Shulman and Levine2012; Sax Reference Sax and Ehlrich2000) and such norms are associated with more participation by individual students (Astin Reference Astin1993, 116; Campbell Reference Campbell2006, 158, 2008, 2009; Glynn, Huge, and Lunney Reference Glynn, Huge and Lunney2009). By implication, then, attending an affluent campus may boost participation.

Of course, many campuses are not hotbeds of political activity. However, some campuses do have a more active student body than others. The literature gives us reason to expect that more politically engaged campuses foster political engagement (Astin Reference Astin1993, 116; Campbell Reference Campbell2006, 158, 2008, 2009; Glynn, Huge, and Lunney Reference Glynn, Huge and Lunney2009). Affluent campuses may be more likely to have such norms because they collect students from higher-SES—and thus more politically active—backgrounds.

In sum, low-income students may gain a participation boost from largely affluent schools. Although low-income students may experience some exclusion and difficulty, they may also develop positive identities and learn to participate through exposure to norms of political engagement. This may close the gap with middle- and high-income peers. In that sense, affluent campuses might carry a larger effect (gain) for low-income students than they do for middle- and high- income students.

However, affluent campuses may also provide a participatory boost to middle- and high-income students. In fact, these students may gain more than low-income students do. If participatory norms exist on affluent campuses, affluent students would be exposed to them no less than low-income students, and perhaps more so if they face fewer social and cultural difficulties. As elaborated earlier, some studies find that participatory norms affect students only if they are socially integrated. If class culture theory is correct, middle- and high-income students may more readily absorb the participatory norms present on these campuses.

Next we outline the approach that we use to arbitrate between the positive and negative predictions.

Data and Methods

Our analysis uses panel data collected by the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP), which is part of the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI). CIRP partners with colleges to survey undergraduates about their attitudes and experiences just before they begin college (the Freshman Survey, or TFS) and again at the end of college (College Senior Survey, or CSS); refer to the online appendix, p. 2.

Panel data provide one way of alleviating—though not resolving—the problems posed by self-selection. Low-income students’ pre-college level of political engagement may influence their probability of attending affluent colleges, biasing the effect of campus affluence on senior-year political engagement. The panel data allow us to partially account for this possibility in three ways. First, we use lagged dependent variable models to control on the respondent’s pre-college level of political engagement. That is, we regress the Wave 2 dependent variable on the same variable from Wave 1 (or a proxy for it). Second, as an additional test for selection bias, we subset low-income students by pre-college political engagement. Third, several additional tests of self-selection are also described after the main results. These approaches do not allow the strong causal inference of randomization, but they represent a better-identified design than is currently common in the literature on educational contexts.

The freshman wave spans incoming cohorts from 1989–2009. The senior re-interview wave spans 1994–2013. The response rate is very high, typically above 75%. The effective sample consists of up to 201,011 students: 13,363 low-income, 91,257 middle-income, and 96,391 high-income students. (We explain our income measure in the next section.) The sample includes up to 571 schools that vary considerably in size, private or public status, region, student body demographics, and selectivity. To calculate cohort-level predictors we pool consecutive pairs of cohorts, drawing from a supplementary freshman CIRP sample containing approximately eight million students. We use cohorts with a minimum of 100 individuals.

Our analysis uses multilevel models with random intercepts for schools and cohorts, and graduation-year fixed effects (Gelman and Hill Reference Gelman and Hill2007). The year fixed effects allow us to account for changes over time, including changes in the school’s affluent composition. We use multilevel logistic regression for binary outcomes and multilevel linear regression for continuous outcomes (scaled to range from 0 to 1). In each model, we regress the political engagement outcome from senior year onto campus affluence, which is our predictor of interest, controlling on the respondent’s freshman response (or a proxy for it) and a set of additional control variables.

Throughout, we estimate models separately by student’s household income (low, middle, or high). This allows us to test the hypothesis that affluent campuses may affect students differently by their class background. This approach can reveal whether low-income students respond more, less, or the same as middle- and high-income students do to affluent environments. We then directly test whether the effects differ across these subsets. Question wording, coding, and distributions for all variables are in the online appendix, tables 1 to 4, starting on p. 4.

Independent Variables

We use a categorical rather than continuous measure of income. This allows us to capture non-linearities and to ensure adequate variance at extreme values, which is especially important in interaction models (Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019). Specifically, we measure three categories of student income: Low-income respondents are those whose reported parental income is at or below the twentieth percentile of the national household income distribution during freshman year. High-income respondents are those at or above the ninetieth percentile (following Gilens Reference Gilens2012). The remaining respondents are coded as middle-income. Other work reports robustness checks on this measure, including adjustments for geographic variation (Mendelberg, McCabe, and Thal Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017).

Campus affluence is the proportion of high-income students in the student’s freshman cohort and the preceding freshman cohort, divided into five categories, each holding a quintile of the low-income students in our data. These categories are for cohorts with less than 23% affluent; 23% to 32% affluent; 32% to 42% affluent; 42% to 55% affluent; and more than 55% affluent students. The distribution of low-, middle- and high-income students across levels of campus affluence is displayed in the online appendix, figure 1, p. 3. We use this quintile measure because it reflects the variation in campus affluence better than larger categories, such as a binary coding. It also provides a theoretically relevant highest category of campus affluence with a majority of affluent students. Affluent students would shape the social norms most strongly where they are a clear majority. Our models focus on the effects of attending affluent campuses, comparing cohorts with less than 23% affluent students (the omitted category) to those with more than 55% affluent students.

Dependent Variables

First, we combine six items into a continuous index of passive engagement with politics (α = 0.81): interest in “political affairs,” how frequently the student “discussed politics,” desire to influence the “political structure,” desire to influence “social values,” desire to “participate in a community action program,” and desire to “become a community leader.” Second, we measure two forms of electoral participation with an indicator for voting in national elections and an indicator for working on local, state, or national election campaigns, which we label campaigning in our discussion of the results. Third, non-electoral participation is measured by an indicator of protest involvement, which we label protesting in our discussion of the results. Finally, we examine leadership in the collective life of the college community with indicators for whether a respondent was elected to student government and led a campus organization. When educational experiences have an association with later political activity, it is often through engagement with important issues in the school community (Campbell Reference Campbell2008). Taking an active part in one’s community as a student is thus of relevance to future political action. The six outcome variables allow us to examine varied forms of engagement and participation.

Control Variables

Where possible, we control for the respondent’s dependent variable in freshman year. We are able to do so for passive engagement, campaigning, and protesting. When no freshman year version of the dependent variable is available, we control for a proxy. For voting this proxy is freshman year interest in “political affairs.” For elected to student government and led a campus organization, this proxy is desire to “become a community leader.” (Mean freshman values of these measures are generally below the scale midpoint, so ceiling effects are unlikely; refer to the online appendix, table 1.)

Affluent and non-affluent campuses may differ in a variety of ways. We therefore also control for a wide variety of individual, cohort, and school level variables that may be correlated with campus affluence and with participation, all measured at the start of freshman year. Following Hillygus (Reference Hillygus2005) and other studies of education effects, we include indicators for High Standardized Test ScoreFootnote 4 and intention to be a Social Science Major, Humanities Major, Science Major, or Business Major. We include indicators for demographics: Female, Asian, Latino, Black, Other race, Evangelical, Jewish, Catholic, Other or No Religion, English Second Language, and age (Aged 17 or less, Aged 19, and Aged 20).Footnote 5 Following Mendelberg, McCabe, and Thal (Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017), we control for students’ motivation for attending college (Attend To Make Money). Following the approach recommended by Bartels (Reference Bartels and Franzese2015), we control for aggregated versions of each of these individual-level indicators: Proportion High Standardized Test Score, Proportion Social Science Major, Proportion Humanities Major, Proportion Science Major, Proportion Business Major, Proportion Asian, Proportion Latino, Proportion Other Race, Proportion Jewish, Proportion Catholic, Proportion Evangelical, Proportion Other or No Religion, Proportion English Second Language, Proportion Aged 17 or Less, Proportion Aged 19, Proportion Aged 20, Proportion Attend to Make Money, Mostly Female, Mostly Black (the latter two are at the school level). Following Hurtado et al. (Reference Hurtado, Saenz, Denson, Locks and Oseguera2005), we also control for school-level characteristics: whether the school is a college versus a university (College), school size (Large Student Body), public or private status (Public), and school region (Northeast and South).

Additional Variables

We measure intervening and moderating variables to test the hypothesized mechanisms (psychological injury, academic difficulty, social exclusion, institutional stigmatization, financial hardship, and political engagement norms). We also use additional variables to test for selection effects. These are discussed later, after the main results.

Results

Figure 1 shows the predicted percentage point difference in the senior year outcome between a student who attends a school in the lowest category of campus affluence (Less than 23 percent affluent) and a student who attends a school in the highest category (More than 55 percent affluent), separately for low-, middle-, and high-income students, for each dependent variable. These are based on models that control on the freshman-year outcome and the control variables listed earlier; refer to the online appendix, table 7, starting on p. 44.

Figure 1 Marginal effect of majority-affluent campuses on six types of political engagement, by student’s household income

Low-income students benefit from attending affluent schools on three outcomes, shown in the top panels. In two of these outcomes, low-income students benefit more from attending affluent campuses than middle- or high-income students. First, low-income students experience a large, twenty-point effect on leading student organizations. They are much more likely to be leaders in affluent than non-affluent campuses. While the other income groups also experience a positive effect, it is much smaller. Second, low-income students are more likely to protest in affluent than non-affluent campuses, while middle- and high-income students show no effect. Finally, low-income students are more likely to be passively engaged in politics in affluent schools, which is similar for the other students. Interaction models directly testing for different campus affluence effects on low, middle and high-income students reinforce these findings; refer to the online appendix, p. 40.Footnote 6 In addition, measurement error in the proxy lagged DV is not driving these results, since the effects of campus affluence are similar in models using actual and proxy lagged dependent variables.

Low-income students experience small to moderate, though statistically insignificant, effects on two of the three remaining outcomes in figure 1. These effects are comparable in size for lower- and higher-income students, though they are less precise for low-income students. On voting, middle- and high-income students see statistically significant, moderate increases (six and four points, respectively), and low-income students see a non-significant but similar effect (four points). Similarly, on campaigning, only middle-income students benefit in a statistically discernable way, a small effect similar in size to the non-significant effect for low-income students. Finally, on being elected to student office, no income group sees an effect.

The appendix shows the results of a model without controls. The effects of campus affluence are largely consistent with those presented in figure 1, with a loss of some statistical precision and magnitude in only four of the eighteen models in the online appendix, figure 4, p. 36.

These results provide the first evidence we know of about how affluent communities shape the political participation of low-income young adults. The results support the positive predictions in three ways. First, we can reject the hypothesis that campus affluence has negative repercussions for low-income students on any of the six outcomes. Campus affluence never takes a statistically significant negative sign for these students. Second, campus affluence has positive and statistically precise effects for low-income students on passive engagement, protest, and especially the leadership of campus organizations. Protests are an important mechanism through which low-income Americans achieve policy representation (Gause Reference Gause2016). By increasing their tendency to protest, affluent campuses may be providing low-income students an instrumental means of attaining representation. Similarly, when low-income students gain access to leadership positions, they are building organizational and civic skills that are likely to translate into continued leadership later in life (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Third, these gains would be problematic if they went hand in hand with even greater gains for middle- and high-income students. However, there are only two outcomes—voting and campaigning—where middle- or high-income students gain more than low-income students, and even here the difference is very modest. Affluent campuses do not increase the income gap in participation.Footnote 7

On the other hand, the results do not support the notion that college serves as a pathway to political equality. First, the statistically significant positive effects of campus affluence are restricted to forms of participation that operate outside of the formal representational system; on voting and campaigning, the effects are imprecise for low-income students (though of similar magnitude). This is problematic given that the income gap in electoral power is a key political mechanism for the rise of economic inequality (Franko, Kelly, and Witko Reference Franko, Kelly and Witko2016). Second, on activities in which low-income students do gain, high- and middle-income students often gain as well.

We can compare these effects to the effects of variables from other studies of the impact of college. These include college major (and the proportion of students in those majors), academic achievement, college selectivity, racial diversity, religious composition, age composition, campus norms of materialism, historically black colleges, women’s colleges, private or public schools, colleges or universities, student body size, and region. None of these predictors have consistent effects that are of comparable magnitude to the effects of campus affluence among low income students with the exception of women’s colleges. Attending a women’s college boosts passive engagement, voting, protest, and the likelihood being elected to student government.Footnote 8 With the exception of academic selectivity, no individual-, cohort-, or school-level variables are highly correlated with campus affluence, for students of any class background. Students in affluent and less-affluent schools do not differ substantially in pre-college factors such as gender, race, religion, age, intended major, or political interest; refer to the online appendix, p. 22.

These results speak as much to non-affluent campuses as they do to predominantly affluent campuses. Because the analysis accounts for the pre-college baseline, the predicted senior-year outcome represents the effect of attending the most versus the least-affluent schools net of the starting point. As discussed earlier, we observe positive effects on some outcomes and no negative effects. This suggests that in terms of political participation, low-income students are better off attending affluent than non-affluent schools.

Extensions and Robustness Checks

We extend these results in several ways. First, we conduct additional tests to account for the possibility of self-selection. Second, we examine potential mechanisms by measuring the effect of campus affluence on intervening variables (psychological, academic, social, institutional, financial, and political mechanisms). Third, we test whether these variables moderate the effects of campus affluence.

Selection Effects

Our main models already made one effort to address self-selection by controlling on a large number of selection variables, including the individual’s starting level of political engagement. However, the effects may nevertheless be driven by politically engaged students self-selecting into affluent campuses. To further address this concern, we examine subsets of low-income students for whom this form of self-selection is less likely.

First, we re-estimate the main models on subsets of low-income students who chose to attend their college for reasons unrelated to the number of affluent students on a campus or political engagement (Card Reference Card, Christofides, Grant and Swindinsky1995; Mendelberg, McCabe, and Thal Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017). These are students who (1) chose a college because it was close to home, or (2) were recruited for athletics, or (3) could not afford their first-choice college. These students are relatively constrained in selecting schools, and more likely to base their choices on reasons other than the combined desire to attend campuses populated by affluent students and a propensity to become more politically active. These factors are in fact uncorrelated with campus affluence. While none is a perfect test and we caution against drawing strong causal inferences, collectively they provide some reassurance against selection bias.Footnote 9

Figure 2 displays the marginal effects. These are based on models in the online appendix, table 8, p. 50. We replicate the main results for all six dependent variables among students who wanted to attend college near home, though some effects are less statistically precise, which is to be expected given the smaller number of observations. For students recruited for athletics or who could not afford their first choice, the results largely replicate the main findings where the tests are sufficiently powered. Though some effects fail to reach statistical significance due to smaller sample size, the magnitude generally approximates or exceeds the original estimate across all three subsets.

Figure 2 Marginal effect of majority-affluent campuses on six types of political engagement, for three low-income subsets with limited selection

We also examine the effects among subsets of low-income students defined by their pre-college level of political engagement. One possible explanation for the positive effects we observe for campus affluence is that affluent colleges are more likely than non-affluent colleges to enroll low-income students who are highly engaged with politics. For example, perhaps political engagement makes students more attractive to admissions officers at majority-affluent colleges. To deal with this potentially confounding variable, we subset the analysis based on students’ pre-college level of political engagement. We define these subsets based on the importance assigned to “keeping up to date with political affairs” in the freshman year survey. Based on this question we identify low-income students with a low incoming level of political engagement (those who answered “not important”), a medium incoming level of political engagement (those who answered “somewhat important”), and a high incoming level of political engagement (those who answered “very important” or “essential”); refer to the online appendix, p. 37, for more details. We find similarly sized effects of campus affluence across all three subsets. Campus affluence does not only have positive effects for low-income students who are already engaged with politics prior to college; refer to the online appendix, figure 5, p. 38. Testing the effects of campus affluence, a non-randomized treatment, at various levels of pre-college political engagement, a potential confounder, provides added confidence in the results (Nall Reference Nall2018, 60-62).

Intervening Outcomes

Next, to test the proposed mechanisms, we examine the effect of campus affluence on a set of theoretically relevant intervening outcomes. These intervening variables may help explain the positive effects of campus affluence if they themselves are positive outcomes of campus affluence (for example, the cohort’s political norm). If they are negative outcomes of campus affluence (for example, low self-confidence), they may imply that the positive engagement effects of campus affluence may be muted by negative countervailling mechanisms. We measure these variables at the individual and aggregate levels, as theoretically appropriate.

At the individual level, we include emotional health and motivation to lead (psychological mechanism); academic competence (academic mechanism); social self-confidence and social satisfaction (social mechanism); and the number of hours worked for pay (financial mechanism). These assess mechanisms pertaining to the student’s individual experiences and resources. The models again control for the freshman-year outcome and are otherwise identical to the main models.

At the aggregate level, we include two intervening variables. First, we measure the cohort’s freshman level of passive engagement (the political norm mechanism). Second, we measure the proportion of low-income students’ educational expenses that is paid by the school, the “low-income aid ratio” (the institutional practices mechanism). These average the responses of all students, or all low-income students, respectively, in the student’s freshman cohort. We choose to measure these variables at freshman year as they test hypotheses about characteristics of the campus in place at the beginning of the student’s college experience. This allows us to assess whether students who matriculate to more affluent campuses are also matriculating to campuses with stronger norms of political participation (as the political norm mechanism suggests) or practices that may especially affect low-income students (as the institutional mechanism suggests). As these are cohort-level outcomes, all aggregate measures from the main model are retained as controls, the intercept randomly varies at the school level, and the number of individuals used to estimate each cohort value is used as a weight in the analysis.

All measures are described in the online appendix, p. 28, as are additional measures used for robustness. (The robustness measures are less ideal, since they have more missing observations and lack freshman-year values, but the results are similar).

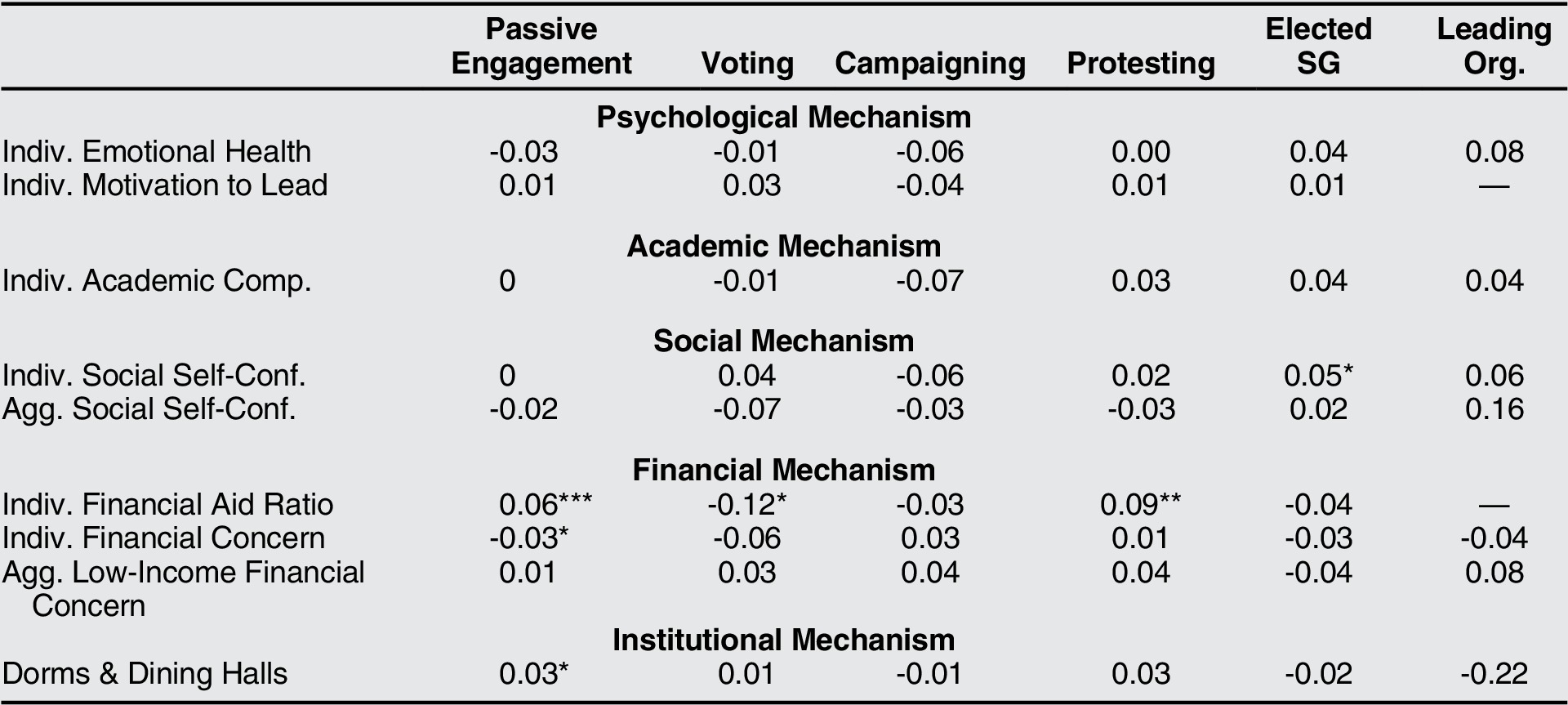

The results are in table 1, which displays the marginal effects (based on the online appendix, tables 12 and 13, pp. 56-57). Consistent with its positive effects on political engagement, campus affluence provides a more positive college experience for all students, including those from low-income backgrounds. We observe positive effects for low-income students on the psychological mechanism (emotional health and motivation to lead), the academic mechanism (academic competence), the social mechanism (social self-confidence, but not social satisfaction), and the political mechanism (the cohort political norm). All of these may contribute to the positive effects of campus affluence on political engagement.

Table 1 Marginal effect of majority-affluent campuses on intervening outcomes, by student’s household income

Notes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. The values are marginal effects, in percentage points, of campus affluence on each intervening outcome. These marginal effects are estimated at the individual level for the Psychological, Academic, Social, and Financial mechanisms, and at the cohort level for the Institutional Practices and Political mechanisms.

To test whether any of these mechanisms might account for campus affluence effects, we conduct mediation analyses. To be sure, it is difficult to estimate mediation effects without bias. We thus treat the mediation analysis as merely suggestive. We focus on the cohort political norm, which was the only cohort measure associated with campus affluence in table 1, and thus has the best potential to explain the positive effects of affluent campuses. When we include the cohort’s freshman level of passive engagement in our main models of low-income students, the positive effects of campus affluence show modest declines of 15% and 27% on passive engagement and campus organization leadership respectively, and the effect of campus affluence on campus organization leadership loses statistical significance; refer to the online appendix, p. 38.Footnote 10 This is consistent with the explanation that norms of political engagement contribute somewhat to the positive effects we find for campus affluence. However, the other campus affluence effects remain mostly unaffected, indicating that campus affluence might also matter independently of the cohort political norm. When we measure the cohort political norm in alternative ways, such as the average level of voter turnout in a students’ cohort, we find similar results, with the norm having few meaningful effects (Appendix p. 38). Thus, while it is clear that more affluent campuses are also more politically active, the effects of campus affluence do not appear to generally rest on the levels of political activity on campus.

This test also helps to further address concerns about selection bias in the estimated effect of campus affluence. While the mediation analysis considers the freshman cohort’s level of engagement as a substantive mechanism, it may alternatively be regarded as a confound, as we noted in the section on selection effects. We do not regard this variable as a potential confound—it is implausible that a cohort’s freshman-year engagement causes that cohort’s freshman-year household affluence. But even if it were a potential confound, the results of the mediation test suggest that it does not function that way in practice, as little of the campus affluence effect can be attributed to it. This mediation analysis thus reinforces the results of the subset analysis in the selection effects section. The campus affluence effect does not seem to be driven by politically active students self-selecting into affluent campuses.

We note that table 1 also reveals some ways in which low-income students fare poorly at affluent colleges. Low-income students do not gain, while more affluent students do gain, on social satisfaction (a social mechanism) and on working fewer hours for pay (a financial mechanism). Still, these do not translate into a net negative participation effect on low-income students, as we did not find such effects in figure 1.

Overall, this analysis reveals a broad range of ways in which low-income students benefit from attending affluent campuses. However, we do not find that any of these benefits can entirely explain the positive effects we find for low-income students’ political participation. Our effects thus appear to come directly from attending an affluent college campus. As we cannot rule out omitted confounders, this conclusion is tentative and requires further study, but it is consistent with our previous results.

Moderation Effects

Finally, we examine variables that may condition the effect of campus affluence on low-income students. Unlike the intervening variables analysis, this moderation analysis only includes variables that meet the exogeneity assumption: they are uncorrelated with campus affluence and are measured in the freshman wave (with an exception explained later). We measure these at the individual and aggregate levels where possible; refer to the online appendix, pp. 33-35.

These variables correspond to the mechanisms discussed in the theory section. For the psychological mechanism, we use the individual’s emotional health and motivation to lead (not the cohort versions, which are correlated with campus affluence). For the academic mechanism, we use the individual’s academic competence (not the cohort version, which is correlated with campus affluence). For the social mechanism, we use social self-confidence at the individual and cohort levels (neither is correlated with campus affluence). All the foregoing variables are freshman-year versions of senior-year measures from the intervening analysis.Footnote 11 For the financial mechanism, we replace the measure of working fewer hours for pay, which is unavailable in the freshman wave, with three measures that are available in the freshman wave: the individual-level financial aid ratio (defined earlier),Footnote 12 and individual- and aggregate-level measures of concern with one’s ability to finance college (measured for low-income students). For the institutional mechanism, we omit the aggregate financial aid ratio used earlier because it is correlated with campus affluence, replacing it with a binary measure of whether dorms and dining halls remain open during breaks. This institutional practice may pose particular hardships for low-income students, who often lack the funds to travel home during breaks. To create this measure, we collected novel data from the schools in our dataset. By searching schools’ websites and contacting schools directly, we are able measure this variable for 248 of our 571 schools (43%). Finally, we omit the cohort’s political norm, which was used in the previous intervening analysis, as it is correlated with campus affluence.

The results are in table 2. Only one variable has statistically significant moderating effects for low-income students on at least two outcomes: The individual’s financial aid ratio. This financial aid variable boosts the positive campus affluence effect on low-income students’ passive engagement and protest. Only those who receive more generous financial aid experience the positive effects of campus affluence; students who receive relatively little aid show a null campus affluence effect; refer to the online appendix, p. 34.Footnote 13 That is, low-income students benefit from attending affluent schools only when they are provided financial assistance. This finding lends support to the resource model of political participation (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012). It also carries policy implications, as aid is a resource that schools partially control and could increase.

Table 2 The difference in the marginal effect of majority-affluent campuses at low and High Levels of Moderating Variables, For Low-Income Students

Notes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. The p-values are for the interaction of the highest affluence and high moderator indicators. Blank cells indicate instances where the sample size was too small to run the moderator analysis.

Conclusion

Family income is a powerful predictor of whether a young person obtains a college degree. This in turn means that most colleges are composed of a plurality or majority of affluent students, even among schools established to provide upward mobility. What are the effects of these affluent places on the SES gap in political engagement? Given that a college degree is associated with high levels of political participation and influence, does it function as a democratic equalizer when it comes to civic and political action?

We find that predominantly affluent campuses are associated with higher levels of participation compared to campuses with few affluent students, on most types of political engagement, even when accounting for students’ political engagement at the beginning of college. The magnitude of the campus affluence effect is comparable to the effects of other predictors of participation, such as turnout interventions (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2008). By aggregating many individuals with a proclivity to engage with politics, affluent campuses may create stronger norms of political engagement (Campbell Reference Campbell2006). These norms may help to account for the positive impact of predominantly affluent schools.

Low-income students see a modest but substantively and statistically meaningful positive effect on leading a student organization, protesting, and passive political engagement, where their gains from attending predominantly affluent campuses are at least as great, if not greater, than those of other income groups. They also see a substantively meaningful though statistically imprecise effect on voting, a gain similar to that of other students. On the two remaining forms of engagement—campaigning and being elected to student government—low-income students do not experience large gains, but neither do other income groups.

These findings fail to support the predictions from the theory of cultural mismatch. We do not find any evidence that affluent campuses stigmatize low-income students psychologically, academically, socially, or through exclusionary institutional practices more than non-affluent campuses. To be sure, affluent campuses do better by affluent than low-income students when it comes to satisfaction with the campus social experience and reducing the hours spent working for pay. But low-income students do not experience a decrease in these, or in any other mechanism, from attending affluent versus non-affluent campuses. Moreover, none of the intervening variables substantially weakens the positive effects of campus affluence on their political engagement. While some studies support the idea that people internalize their lower-class status and feel stigmatized in affluent environments, we do not find evidence for these “hidden injuries of class.” Instead, the results support the hypothesis that low-income students overcome the adversity of class-cultural mismatch and gain psychological and political empowerment. That conclusion is consistent with Soss (Reference Soss1999), who found that class-stigmatizing experiences are associated with low external but high internal political efficacy. More generally, these findings support the increasing scholarly focus on resilience in the face of difficulty (Hillygus, Holbein, and Snell Reference Hillygus, Holbein and Snell2015).

That said, class disadvantage does affect the ability of individuals to benefit from affluent environments, through concrete resources. Financial aid conditions the positive effect of affluent campuses for low-income students on some forms of political engagement. When it comes to protesting and to developing an interest in politics, low-income students benefit from affluent campuses only if they receive aid. Concrete resources matter for the SES gap in participation, not only directly, but by shaping how a person responds to the social environment. The policy implications point toward the need for financial support for low-income students. More generally, the results highlight the importance of concrete resources as interventions in economic inequality.

The longstanding conclusion that education is a major predictor of political behavior has been called into doubt by recent findings that college may not carry a causal effect (Berinsky and Lenz Reference Berinsky and Lenz2011; Kam and Palmer Reference Kam and Palmer2008). While we cannot address the impact of attending versus not attending college, this study can compare the effect of attending one versus another type of college. The findings here, which rely on a panel design, various tests for selection effects, cross-campus measures of particular college experiences, and an unusually large sample suggest that college may matter. However, the effects of college may accrue not by mere attendance as much as through particular types of experiences (Hillygus Reference Hillygus2005). Among those experiences is the neglected variable of campus affluence. We caution that the study is unable to draw strong causal conclusions, though it does offer a step in that direction relative to the existing literature on the impact of college experiences on political behavior.

The results carry implications for college as an engine of political and social mobility. Mettler recently labeled American higher education a “caste system, separate and unequal for students with different family incomes” (2014). Concentrated affluence is one way in which this claim may be true. The few low-income students who manage to attend predominantly affluent schools do gain participatory resources relative to those who attend non-affluent schools, and the vast majority, who do not attend such schools, lose out on that benefit. However, on most forms of political engagement, affluent campuses do not provide a substantially larger boost for low-income students than their higher-income counterparts. In that sense, affluent schools neither expand nor narrow the SES gap in political engagement. If students exit in the same relative position they entered, then the gap between the affected individuals does not close, although the gap in the overall population may close slightly. Given that many campuses are disproportionately affluent, the contemporary system of higher education may not be serving as a powerful force muting inequality in politics.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720000699.