INTRODUCTION

The protest of the feminist punk-rock group “Pussy Riot” in Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 2012 provoked a strong reaction from the Russian ruling class. In particular, the State Duma reacted very quickly and Russian President Vladimir Putin consequently signed the amendment to the Criminal Code which newly defines insulting the feelings of believers as a criminal offense.Footnote 1 The new law was then used in an increasing number of cases such as the criminal prosecution of Ruslan Sokolovsky, a 23-year-old video blogger from Yekaterinburg, who, in 2016, played the “Pokemon Go” video game inside the city's famous Temple on BloodFootnote 2 and later received a three and half year suspended sentence.Footnote 3

These political and legal reactions as well as the subsequent sentences were wholeheartedly welcomed by the top leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). Patriarch Kirill likened the performance of Pussy Riot to the times of Napoleon's invasion of Russia, insinuating that both were similar attacks on Russia, threatening it with “blasphemy and outrage” (The Globe and Mail 2012). Also, the conviction of Sokolovsky was commended by the Church, which argued that the court's decision was in fact humane (RIA Novosti 2017) and fully consistent with international practice (Life 66 2017).

These two cases, while unrelated in processual terms, are just two examples of a broader trend of increasing political proximity between the ROC and the State. The connection is clearly visible elsewhere too. One can see the Church's priests sprinkling holy water on the S-400 missile system in Crimea (Radio Svoboda, Krim Realii 2018) and the MS-11 “Soyuz” space rocket in the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan (Radio Europa Liberă 2018) or heading the Сhristian procession together with the road inspection police in Krasnodar.Footnote 4

Indeed, the Church has become nigh omnipresent in the Russian society in recent decades. Tens of thousands of churches were built in Russia;Footnote 5 the Moscow Patriarchate-owned TV channel “SPAS” started to broadcast for Russia and the post-Soviet states in 2012; the weekly TV program The Word of the Pastor is broadcasted on the First Federal Channel, which reaches viewers in 190 states. To increase the patriotic spirit of the Russian army, the Main Church of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation was built in the “Patriot” Park in Moscow Oblast in 2020, with its construction being funded by donations of the Russian army; the church is not only the third-largest church in Russia, but also the most recent symbol of the triangular connection between patriotism, the military, and the Church in Russia. While the original aim of the Russian authorities was to strengthen the Church as a legitimizing force for the government, the Church sees itself in more ambitious terms—as an active reformer of the social life of the laity.

This article explores the intense interactions between the ROC and the State, primarily in relation to patriotic education. It starts by showing that discursively, patriotism and patriotic education have become key notions around which the relationship between the Church and the State revolves. To achieve this goal, we provide a systematic analysis of the evolution of the Church's discourses on patriotism and patriotic education. We analyze the speeches of Patriarchs Alexiy and Kirill delivered within 2004–2017 and state programs on patriotic education and explore the relations between patriotism and religion in these documents. Apart from patriotism and patriotic education, we are also interested in exploring the ways in which this patriotic narrative is connected to historical memory. Therefore, the article also sheds light on the way historical memory has been (re)imagined by the Church, allowing the ROC to cast itself as a central actor which at times closely cooperates with the State while keeping its distinct narrative of the Russian history. Finally, the article shows that the Church's interaction with the State and specific reading of Russia's history and its present struggle with the West lead to the militarization of Orthodox patriotism, which allows for even more cross-pollination with the policies of the Kremlin.

THE STATE OF THE ART: THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH and THE STATE

Considering the continuously increasing visibility of the Church in Russian political life, it is not surprising that the body of literature focusing on the relationship between the Church and the State in Russia has been steadily growing. This relationship is complex, however, and the Church's role in it should not be perceived as that of a monolithic actor (cf. Anderson Reference Anderson2007; Mitrokhin and Nuritova Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009; Papkova Reference Papkova2013; Torbakov Reference Torbakov2014). Let us start by noting that the State and the Church cooperate enthusiastically in some areas, but there are also some other important areas where their ways substantially diverge.

The studies of the collaborative aspects of the relationship often focus on the efforts to recreate the Russian empire (Mitrokhin and Nuritova Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009, 318–319) and “to restore Russian greatness and sense of nationhood” (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 195). Both the ROC and the State express a similar skepticism about (the Western type of) democracy (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 190) and demonstrate “a shared discomfort about liberalization and the uncritical acceptance of Western influences on Russian life” (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 188). Furthermore, the Church supports many state-led initiatives, ranging from family-related and social services to anti-corruption measures (Richters Reference Richters2012). Other authors, such as Payne (Reference Payne2010) and Blitt (Reference Blitt2011), explore the foreign policy dimension of the cooperation. Interestingly, this cooperation is not limited only to the post-Soviet states or the historical territories of the Russian empire but is instead delineated in broader cultural terms (Payne Reference Payne2010, 725–727). This kind of cooperation then tries to achieve “spiritual security” for the Russian diaspora abroad (Reference Payne2010, 713), which is perceived as being under attack from the “militant secularism” of Western Europe (Reference Payne2010, 719). Such an instrumentalization of religion is supported by a wide range of political authorities, including high officials, Deputies of the State Duma and even members of the Communist Party (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2009, 169). Blitt goes as far as saying that Russian foreign policy has been largely religionized (Reference Blitt2011, 456).

These and other examples of cooperation are open to several lines of interpretation. Some researchers argue that the relationship between the State and the Church is very asymmetric, with President Putin playing the dominant role and the Church being a mere tool to achieve his political goals (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 198). Others, such as Mitrokhin and Nuritova, however, argue that the Church has not been “an obedient tool of the Russian government” (Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009, 318). For instance, the Church promotes “a ban of abortion” and a “strict moral censorship of television” (Mitrokhin and Nuritova Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009, 319), which go far beyond what the secular legal framework stipulates. Similarly, Katja Richters points to the idiosyncratic way the Church reacted to the modernization program of President Medvedev (Reference Richters2012). The differences also pertain to foreign policy. For instance, the Patriarchate refused to “absorb the Abkhazian Orthodox parishes after the Russo-Georgian War of 2008” (Papkova Reference Papkova2013, 250, cf. also Mitrokhin and Nuritova Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009, 319). The divergence of the Church's position from the State's is also related to the ROC's complexity. While the Church leadership may be supportive of the State's policies, there are various subcultures present in the Church and these sometimes oppose both the Church's top authorities and the Kremlin (Torbakov Reference Torbakov2014, 148).

Another study of the differences between the State and the Church is that of Suslov (Reference Suslov2014), which explores the State-Church cooperation in shaping the geographical imagination through the ideas of Russkii mir. Suslov shows that the Church simultaneously promotes another concept, the idea of “Holy Rus”. In this interpretation, the Church constructs a collective identity based on the Orthodox faith, the Russian language, and historical memory, according to which “Russia retains a central position, whether in Eurasia, in a Slavic union, or in “Orthodox Christian civilization”” (Suslov Reference Suslov2014, 77). In this sense, the Church does support the activities of the State but does so in parallel with the State rather than in conjunction with it.

The specific political role of the Church is perhaps best visible in its attempts to impose a traditionalist normative agenda, which long preceded the conservative turn of the Russian political mainstream. Several scholars have already explored this imposition of a traditionalist normative political agenda, be it in the form of the anti-Western and anti-liberal rhetoric of Orthodox fundamentalists (Verkhovsky Reference Verkhovsky2002, 341–343), the Church-led “re-Christianisation” of secular morality (Agadjanian Reference Agadjanian2017), or a conservative response to Western liberalism (Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl2016). Alexander Agadjanian argues that the attack on secular morality draws upon “a partly imagined ethos of imperial Russia and the late Soviet Union” (Reference Agadjanian2017, 1), which had been rather selectively used by the Church's leaders (2017, 5–6). Similarly, the Church's moral discourse targets an “imagined, typified western liberal ethos” (Reference Agadjanian2017, 16). It is these liberal values of the Western(ized) “aggressive minority” that the “moral majority” has to resist (Agadjanian Reference Agadjanian2017, 12). Kristina Stoeckl also shows that the Church's activity as a norm entrepreneur is not only internally driven, but also comes as a response to the “liberal and egalitarian evolution of the international human rights system” (Reference Stoeckl2016, 134).

In this article, we are specifically interested in the historical memory building by the Church. As far as historical memory is concerned, multiple scholars explore the way through which the Church has turned from a mere tool in the hands of the State, as it was during Stalin's exploitation of the Church in WW II (see, for instance, Kalkandjieva Reference Kalkandjieva2015), into an independent actor; or from a “suppressed institution” into one “suppressing other religious bodies by discouraging religious pluralism and enjoying state-sanctioned privileges in a secular country” (Knox Reference Knox2005, 1). Some shed light on the ways the Church imbues historical sites such as the Gulag with religious symbolism or how the murdered Tsar Nicholas II is used in connecting historical memory with the Church (Bogumił, Moran, and Harrowell Reference Bogumił, Moran and Harrowell2015). To give another example of this trend, an excellent text by Laruelle (Reference Laruelle2019) shows that the commemoration of the February and October 1917 revolutions is interpreted, in contrast with the state-sponsored attempt to reconcile both events, as a “Russian national tragedy” by the Church (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2019, 12). Another specific divergence of the Church from the state authorities concerns the problem of “interpretation of history, specifically of Stalinism” (Papkova Reference Papkova2011, 678).

Another realm of State-Church cooperation which is particularly relevant for this article is related to the Orthodox patriotic education. Much attention has been dedicated to the implementation of the curriculum titled “The Fundamentals of Orthodox Culture” in public schools. Even though before 2008 the whole process was highly contentious and some Russian policy-makers openly disagreed with the Church's attempts to teach Orthodox culture in public schools (Papkova Reference Papkova2009), the Church's triumph following Medvedev's presidency is difficult to deny (Papkova Reference Papkova2011). Joachim Willems, who explored these changes very early on, argued that the introduction of Orthodox culture in public schools was substantiated by the perceived need of morality and moral education and that these were imbued with religious meaning: “As far as education in patriotism is concerned, the argument about fearing God is joined with the argument about heavenly rewards: it is the hope of eternal life that motivates one to risk one's life in war” (Willems Reference Willems2006, 291). Finally, Tobias Köllner explored the cultural and religious impact resulting from the curriculum's implementation in the Vladimir Region, showing that even though the public education is officially secular, the education is hardly neutral and Orthodox clergymen play a strong role in instilling pro-Orthodox attitudes in the pupils (Köllner Reference Köllner2016, 373).

In our article we employ a critical discourse analysis (CDA, cf. Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1993; Wodak Reference Wodak, Seale, Gobo, Gubrium and Silverman2004; Fairclough Reference Fairclough2013; Wodak and Meyer Reference Wodak and Meyer2016a; Reference Wodak, Meyer, Wodak and Meyer2016b), specifically using some of the instruments described by Ruth Wodak as part of her discourse-historical approach (Wodak and Meyer Reference Wodak and Michael2001; Wodak Reference Wodak, Seale, Gobo, Gubrium and Silverman2004). Our approach thus starts from the assumption that discourses are essentially social practices with a substantial impact on both politics and society (Wodak and Meyer Reference Wodak, Meyer, Wodak and Meyer2016b, 6). Discourse analysis helps us to uncover how some political measures are made possible or even desirable and others are framed as unsuitable or even entirely excluded from the realm of the possible. The critical aspect in our approach aims at shedding light on how the dominant political narrative is legitimized and framed as logical and natural while the opposing narratives are further marginalized. In this way, CDA not only shows how political narratives and frames are constructed, but also how these can be used to manipulate the public to achieve certain political ends (Jancsary, Höllerer, and Meyer Reference Jancsary, Höllerer, Meyer, Wodak and Meyer2016, 199).

More specifically, we explore three discursive strategies from the CDA instrumentarium, as introduced by Wodak (Reference Wodak, Seale, Gobo, Gubrium and Silverman2004). These strategies are those of nomination, predication, and argumentation. In the studied case, the strategy of nomination is a way through which the speaker identifies and describes the key actors and concepts (for our results see Tables 1–3) in the promotion of Russian patriotism as well as their positions in regard to patriotic education and Russian history. The strategy of predication assigns values to these actors and their policies, showing which are good/rational/patriotic and which are to be shunned as evil/foolish/unpatriotic (again the results are summarized in the three tables below). Strategies of argumentation tie these discursive elements into one coherent narrative and try to convince the audience that the argument should be accepted, along with the policies the speaker advocates. Finally, CDA also pays attention to intertextuality and the context—hence we also provide an analysis of Church “patriotic” policies which are framed by the analyzed discourses. This is complemented by the identification of the key “topoi”, discursive elements that are central to the arguments made.

Table 1. Discursive strategies: the evolution of the Church cooperation with the State

Table 2. Discursive strategies: Russian Orthodoxy and patriotic education

Table 3. The role of the West in the Church's discourse

Our textual corpus consisted of two types of texts: First, we focused on the state programs of patriotic education and the specific connection between patriotism and religion in these documents. The crucial role of religious actors in supporting the patriotic education of children and youth is stipulated by three out of the five analyzed state programs (2001–2005, 2003, 2006–2010), as well as the draft law of 2017, which also stresses the primary importance of the ROC. Second, we analyzed 233 speeches pronounced by the Patriarchs Alexiy and Kirill within the 2004–2017 period (http://www.patriarchia.ru).Footnote 6 Due to the large amount of data which we had to analyze in the writing of this article, Atlas.ti 8.0 was used as an assisting software.

The analytical part of the article is divided into three sections. In the first, we aim to explore the rhetoric as well as the activities of the Church in the field of patriotic education and the gradual convergence of its position with that of the state authorities. In the second, we explore the role of historical memory and the specific interpretation thereof by the religious leaders, whose narrative is complementary to, yet distinct from the official account given by the Russian President(s). In the third part, we shed light on the Church's contribution to the militarization of Orthodox patriotism and its relevance for the State–Church relationship.

PATRIOTIC EDUCATION: STATE-CHURCH CONVERGENCE AFTER 2005

Beginning in the 1990s, the Moscow Patriarchate has voiced a number of political demands, which spanned from the restitution of its property, through the introduction of Orthodox education in public schools and the establishment of the institute of military priesthood in the armed forces, to a restriction of religious pluralism (Davis Reference Davis2002, 661–664; Papkova Reference Papkova2011, 669). While already during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin the Church was given a number of tax exemptions (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 187), the access of the Church to the public schools and the presence of priests in the army were still denied (Mitrokhin and Nuritova Reference Mitrokhin and Nuritova2009, 310). The political presence of the Church and its proximity to the State, however, continued to increase. In 2009, priests who were ministering to the armed forces were provided salaries (Papkova Reference Papkova2011, 675). In 2010, the Orthodox culture curriculum was adopted in public schools and the law on restitution of ecclesiastical property was approved (Papkova Reference Papkova2013, 245–246; Anderson Reference Anderson2016, 260). Other religions were “hierarchized” in the sense of Agadjanian's concept of “hierarchical pluralism”, with Orthodoxy “as the norm of religious life, corresponding to both the aims of the State and the expectations of the nation” (Anderson Reference Anderson2016, 253).

A close cooperation with the State has not always been seen as an ideal by the Church. In the 1990s and up until 2007, Church leaders frequently insisted on acting independently from the State, and the Church nominational discourses kept the two entities separate (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997; Reference Alexiy2005a). In particular, for Patriarch Alexiy II, the Church's involvement in politics was absolutely unacceptable (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997). By drawing parallels with the Soviet period (but also with previous periods), when the Church was fully controlled by the State, Alexiy II argued that “…if at the given historical time the Church does not exist as an independent institution, then it is going to turn into another governmental department… The Church had already been such a governmental department before 1917” (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006b). To stress this argument, Alexiy II repeatedly claimed that “[t]he Church of Christ is not of this world” and that the Church would not “get involved in the political struggle, in the ruling of the state” (Reference Alexiy2007a).

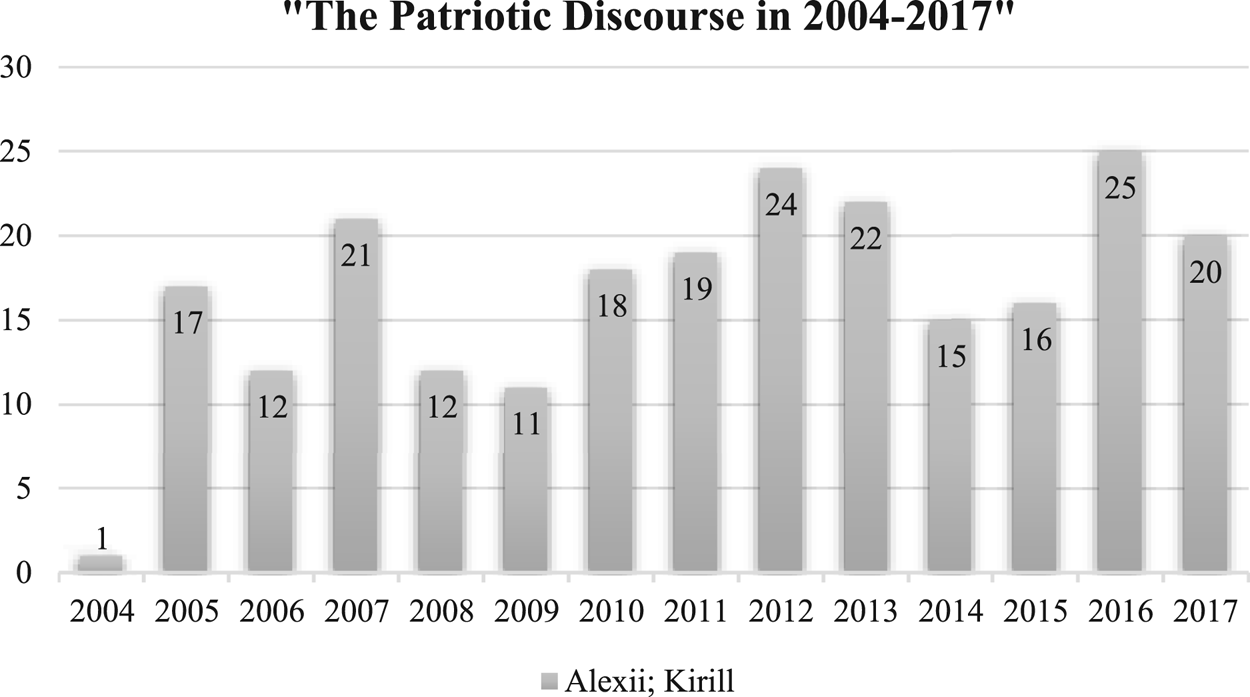

While the Church's rhetoric already started to change around 2008, the watershed was the coming of Alexiy's successor, the Patriarch Kirill, when a quick rapprochement with the State started; this led to the new position of the Church being firmly established around 2010 (Kirill Reference Kirill2008b; Reference Kirill2010g; Reference Kirill2014b; Reference Kirill2015g). The topic around which the convergence with the State revolved was patriotism and the term patriotism started to be used increasingly frequently by both the state officials and church representatives. This was an easy rhetorical move for the Church, as patriotism was already an important topic for the Church before 2008 (see Figure 1). Already in 2005–2007, the Church started to insist on its own specific contribution to patriotic education and the need for a tight cooperation between the two actors in this regard (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2005a; 2005e; Reference Alexiy2006b; Reference Alexiy2007d). During that period, the Church's focus also started to shift towards the teaching of the Orthodox religion in public schools (Alexiy 2005b; Reference Alexiy2006g; Reference Alexiy2007c; Kirill Reference Kirill2009c; Reference Kirill2010a; Reference Kirill2010f).

Figure 1. The patriotic discourse in 2004–2017

Source: Calculated by the authors from the data retrieved from http://www.patriarchia.ru.

The state authorities, on their part, were happy to see the Church's contribution to the State's aims. During Medvedev's presidency, the Church was thus given a broad range of powers to clericalize the Russian society (Papkova Reference Papkova2009; Reference Papkova2013). Again, this was particularly strongly the case in patriotic education (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2009b; Reference Medvedev2009c; Putin Reference Putin2013a; Reference Putin2013b; Reference Putin2016; Reference Putin2017). The importance of the religious actors supporting the patriotic education of children and youth was also stipulated by the state programs on patriotic education of 2001–2005 (Pravitel’stvo Rossiiskoi Federatsii Reference Pravitel’stvo Rossiiskoi Federatsii2001), 2003 (Pravitel'stvennaia Komissiia Reference Pravitel'stvennaia Komissiia2003), and 2006–2010 (Pravitel’stvo Rossiiskoi Federatsii Reference Pravitel’stvo Rossiiskoi Federatsii2005), as well as the draft law of 2017 “On the Patriotic Education in the Russian Federation” (Gosudarstvennaia Duma Reference Gosudarstvennaia Duma2017). According to the State-framed vision, the traditional religions of Russia were expected to contribute to the patriotic education by “forming among the citizens the belief in the need to serve the interests of the Motherland, and in its protection as the highest moral obligation” (Pravitel'stvennaia Komissiia Reference Pravitel'stvennaia Komissiia2003) or “by forming among the citizens the belief in the necessity to serve the interests of the Fatherland and its protection” (Gosudarstvennaia Duma Reference Gosudarstvennaia Duma2017).

The shift towards a closer cooperation with the State was explained in several different ways: at the beginning, Kirill linked the reversal to the understanding of the Church as weak and serving, thus neutralizing the critique that the Church would become too powerful by aligning itself with the State: “The Church is strong by its weakness. It does not have any means to manipulate the public consciousness, to influence the masses politically. The Church awakens the people with its quiet voice” (Kirill Reference Kirill2009d). However, around 2009, Kirill already started to use an entirely different justification: “When the Church leaves the society, when it stops influencing the people's life, a country like Russia fades away as had already happened in the history of Russia” (Kirill Reference Kirill2009a). Simultaneously, politics ceased to be the domain which the Church should not get involved in: “If we continue to argue that politics is a dirty business, that it is not a Christian business, then we would consciously give our lives to those people who are indifferent to Christian values” (Kirill Reference Kirill2008b).

Following this line of argument, Kirill claimed that the Church is the only institution which could deal with the education of youth and give them the comprehensive “philosophical and axiological answers” they need (Kirill Reference Kirill2010i). Out of all the possible areas of cooperation, patriotic education has been repeatedly identified by the Church as the most promising sphere where the Church and the State have to closely cooperate.Footnote 7 The most frequently used predicates in the ecclesial texts on patriotic education are related to schools, youth, children, and family (see, e.g., Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997, Reference Alexiy2006g, Reference Alexiy2007g; Kirill Reference Kirill2012a). Particularly in the Church's main strategic document titled “The Fundaments of the Social Policy” [Основы социальной политики] (2000), the education of children and youth and its patriotic dimension is seen as essential. The Church has conceived its patriotic education of the youth as a comprehensive policy: it has established not only Orthodox kindergartens, Orthodox groups in the state-run kindergartens (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997; Reference Alexiy2004), and Orthodox schools (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2004; Kirill Reference Kirill2015b), but also Sunday schools specializing in military-patriotic education (Kirill Reference Kirill2010i), Orthodox patriotic camps (Kirill Reference Kirill2010f), and patriotic education through the patronage of orphanage houses (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006g) and prisons (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2004; Reference Alexiy2006g; Reference Alexiy2007a; Kirill Reference Kirill2010i; Reference Kirill2015a).

In parallel, the Church also started to encourage the lay believers to partake more actively in the state governance (Kirill Reference Kirill2008b). In a further shift to a more explicit political involvement around 2010, the Church started to directly appeal to the individual patriotic attitudes among the governors, the heads of the banks, and the Commonwealth of Independent States presidents (Kirill Reference Kirill2011a; Reference Kirill2012c; Reference Kirill2013a; Reference Kirill2013c; Reference Kirill2015e). A constant during the whole period was frequent allusions to patriotism in the armed forces (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997; Reference Alexiy2004; Reference Alexiy2006d; Reference Alexiy2007b; Kirill Reference Kirill2012e; Reference Kirill2013b; Reference Kirill2014d; Reference Kirill2015a; Reference Kirill2016a). (See Figure 1, which shows the numbers of references to patriotism in the speeches of both Patriarchs.)

The Church defines patriotism as a dual category which is based on both the love for one's own country and the love for God: “Patriotism is a devotedness to God's intentions regarding your land and your people” (Kirill Reference Kirill2015c). The dual nature of the Church's interpretation of patriotism also pertains to patriotic education. Patriotic education is often carried out alongside “Orthodox education” (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006g; Reference Alexiy2007f), and sometimes they are even combined into “spiritual-patriotic education” [духовно-патриотическое воспитание] (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2004; Reference Alexiy2006e).

This dual understanding of patriotism, which unites the spiritual and the earthly dimension, leads, however, to a strange tension in the way the Church interprets “Christian patriotism”, which becomes both ethnic and transnational. The ROC's document entitled Fundaments of the Social Policy argues that “Christian patriotism manifests itself simultaneously towards the nation as an ethnic community and the community of citizens of the state. The Orthodox Christian aims to love his own fatherland in its spatial dimensions and his brothers in blood living worldwide” (II.3). Hence, on one hand, Orthodox patriotism is imbued with a stress on ethnicity and nationality, which can easily evoke nationalist sentiments. John Anderson also underlines these components of nationalism, pointing to the way Orthodox believers are asked to defend and preserve the country's national culture. He argues that “with Orthodoxy as the national religion, competitors (especially Catholics and “sects”) can be depicted as threats to the religion of the nation, and thus to the nation itself” (Reference Anderson2007, 195).

But Orthodox patriotism cannot be reduced to nationalism and it has a strong civil dimension. For Patriarch Kirill, Christian patriotism transcends territorial borders and unifies people of both one blood and one belief (Kirill Reference Kirill2008b; Reference Kirill2008c; Reference Kirill2009d): “The Russian Orthodox Church is not the Church of the Russian Federation. For today, our non-Russian episcopate is much bigger than Russia's” (Kirill Reference Kirill2009d). Here Verkhovsky is correct in arguing that the Church's nationalism is highly “inclusive” as it unifies the people of the “Orthodox civilization,” which the Church interprets as a cultural category rather than an ethnic concept (Verkhovsky Reference Verkhovsky2011, 27). As a result, Russia and Russians are at its core, but other countries are also constituent parts of the Orthodox civilization, ranging from Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, and Latvia to Kazakhstan (ibid.). This understanding of patriotism as a civilizational defense can then be easily counterpoised against the corrupt West and post-modernist relativism (cf. ibid., 26–28).

For this reason, the Church has also always tried to adapt its patriotic rhetoric to encompass Ukraine and Belarus, as well as other states with significant numbers of followers of the ROC (Kirill Reference Kirill2009d; Reference Kirill2009e). Kirill uses the metaphor of a family in this context, with Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine being three brothers who live next to each other but share the same way of life (Kirill Reference Kirill2009e). The employment of this broader rhetoric was relatively successful during peaceful times when it stressed the countries' commonalities and shared cultural and religious heritage. However, when the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine erupted, the ambivalent nature of the Church's patriotism became untenable. As a consequence, in recent times, the Church has always either sided with the Russian state or, in more sensitive situations, opted for silence.Footnote 8

The two tables which follow summarize the results of our discursive analysis regarding the ROC's cooperation with the State (Table 1) and also regarding the role patriotic education plays in the Church's discourse (Table 2). The third table describes the role of the West in the analyzed speeches and documents, highlighting the specific (and highly negative) role the West has gradually gained in the discourse, thus becoming the Church's most important “other”. Each table presents the results divided into the categories of the three basic rhetorical strategies (nomination, predication, and argumentation), showing also what the key rhetorical elements (‘rhetorical topoi’) were in each of the cases.

What we find particularly interesting is the gradual development of the Church's position regarding the State as well as patriotic education. When comparing the period of 2005–2010 with that of 2011–2017, the difference is striking: the Church initially sees itself as an integral part of the society and as an entity largely independent of politics. Later it is explicitly identified as a political actor with the argument that only the political agency of the Church can prevent a further moral decay of the society. Another, but equally fascinating shift pertains to the discourse on patriotic education. While the Church has always seen itself as central, the rhetoric became much more antagonistic in 2011–2017: in this rhetoric, the Church is now, more than ever, embattled and surrounded by enemies (particularly the secularists in the public schools and liberal media). Hence, the topos of threat becomes dominant in the later phase.

RE-SHAPING HISTORICAL MEMORY: THE CHURCH AS A BEACON IN THE TIME OF TROUBLES

Historical memory and its re-interpretation are not only a key tool in the Church's approach to patriotism but also one of the essential instruments the Church leaders use when presenting the public with the narrative about the Church's importance for the fate of Russia. However, in the Church's discourse, historical memory serves the much more complex function of re-connecting the Church's narrative of Russia's history with its present-day predicaments as well as its policies, both foreign and domestic. In spite of the gradual convergence of the Church and the State, the Church's interpretation has not always been identical with that of the state authorities, sometimes even substantially deviating from the official account as presented by the state authorities. In fact, even inside the Church, there are several subcultures which interpret Russia's history differently (Torbakov Reference Torbakov2014). There is a “Sovietophile” group which considers WW II as a “sacred” event; the Orthodox fundamentalists who oppose the West and vote for the canonization of Ivan the Terrible, Stalin, and Rasputin; and a group holding strong anti-Soviet sentiments, which stays critical of the pro-Soviet positions of some Church authorities (Torbakov Reference Torbakov2014, 163–164).

While the key events of Russian history that are of significance for the present are roughly the same in the Church account as in the official narrative of the leading Russian politicians, there are several historical periods which the Church presents in a specific manner. For instance, in the Patriarchs' speeches, a much stronger stress is put on the periods which are considered tragic for the Church, such as the 1920s and 1930s, as well as the 1950s and 1960s (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006b; Reference Alexiy2006g; Reference Alexiy2007g; Kirill Reference Kirill2017). A similar disagreement pertains to the significance of 1917. In contrast with the state narrative, which regards 1917 as a tragic year in Russian history, the Patriarchs repeatedly also highlight its positive significance since in that year, the Moscow Patriarchate was re-established after almost 200 years of oblivion following the reforms of Peter the Great (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2007c; Reference Alexiy2007g; Kirill Reference Kirill2015b; Reference Kirill2017). Hence, while the 1917 Revolution is typically seen as plunging the state into an even deeper instability, the Church also celebrates the rule of Patriarch Tikhon (Alexiy 2005b).

An analogical difference applies to the 1990s as well. While the decade has been repeatedly interpreted as a negative historical moment by both of the recent presidents of the country, the Church underlines the rebirth of the Patriarchate and the Church's freedom from Communist persecution in that decade (Kirill Reference Kirill2009a; Reference Kirill2009d; Reference Kirill2015g). But exactly this focus on the renewal of the Church has allowed the Patriarchs to connect the Church's interpretation with the presidential interpretation of those years. In this narrative, the 1990s were a new Time of Troubles reminiscent of the period at the beginning of the seventeenth century when the Church was one of the few stable institutions in Russia, unifying the people against foreign invasion (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006b; Kirill Reference Kirill2012b; Reference Kirill2013d; Reference Kirill2015g). Hence, the Church claims that it played a positive role in the 1990s even if the period as a whole was almost as disastrous for Russia as the Napoleonic invasion or the war against Nazi Germany (Kirill Reference Kirill2012b). John Anderson comes to a similar conclusion: “For the church, the chaos of the 1990s represented a moral collapse that it often associates with Western influences and an excessive individualism encouraged by a more open politics.” (Reference Anderson2007, 196).

Interestingly, the new threats to Russia, which started to arrive in the 1990s, are, according to the Church, primarily not of a military nature, but the metaphors and similes used to discuss them are still those related to war—an invasion and a domination of Russia by foreigners or the loss of its sovereignty. The new evils all emanate from the West and they represent “the source of the moral corruption” (Anderson Reference Anderson2007, 189): “wild capitalism” [дикий капитализм] (Kirill Reference Kirill2009b) and consumerism (Alexiy 2005b; Kirill Reference Kirill2009b); the crisis of the traditional family, and the normalization of same sex unions (Alexiy 2005b; Reference Alexiy2006g; Reference Alexiy2007g; Kirill Reference Kirill2008a); the false values of tolerance (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2007g; Kirill Reference Kirill2010i; Reference Kirill2012h); and multiculturalism (Kirill Reference Kirill2010i), all of which still threaten Russia's “spiritual sovereignty” [духовный суверенитет] (Kirill Reference Kirill2015a). To demonstrate how the Western ideology could be hazardous for the state's sovereignty, Kirill draws parallels with the crisis in Ukraine and Ukraine's incapability of resisting the supposedly destructive influence from the West (Kirill Reference Kirill2014c; Reference Kirill2015f).

As a result, Russia is suffering under a continuous assault from the outside, both militarily and culturally (Kirill Reference Kirill2011b). The hazardous “liberal trends emanating from the Protestant societies in the West” make the voices of the Orthodox Churches hardly audible in global ecumenical fora and the Westerners try to impose on the Orthodox Churches alien ecclesiological, moral, and political theories (Kirill Reference Kirill2008a). The Church, in the end, redefined freedom in this manner as well—as the Russian people's desire to be free from foreign influences and their refusal to become slaves of an imported culture (Kirill Reference Kirill2011b). This redefinition then allows the Church leaders to link their argument to the political narrative propounded by the country's ruling elite. The threat from the West has to be countered in a close cooperation of the State and the Church as the struggle is simultaneously military and spiritual.

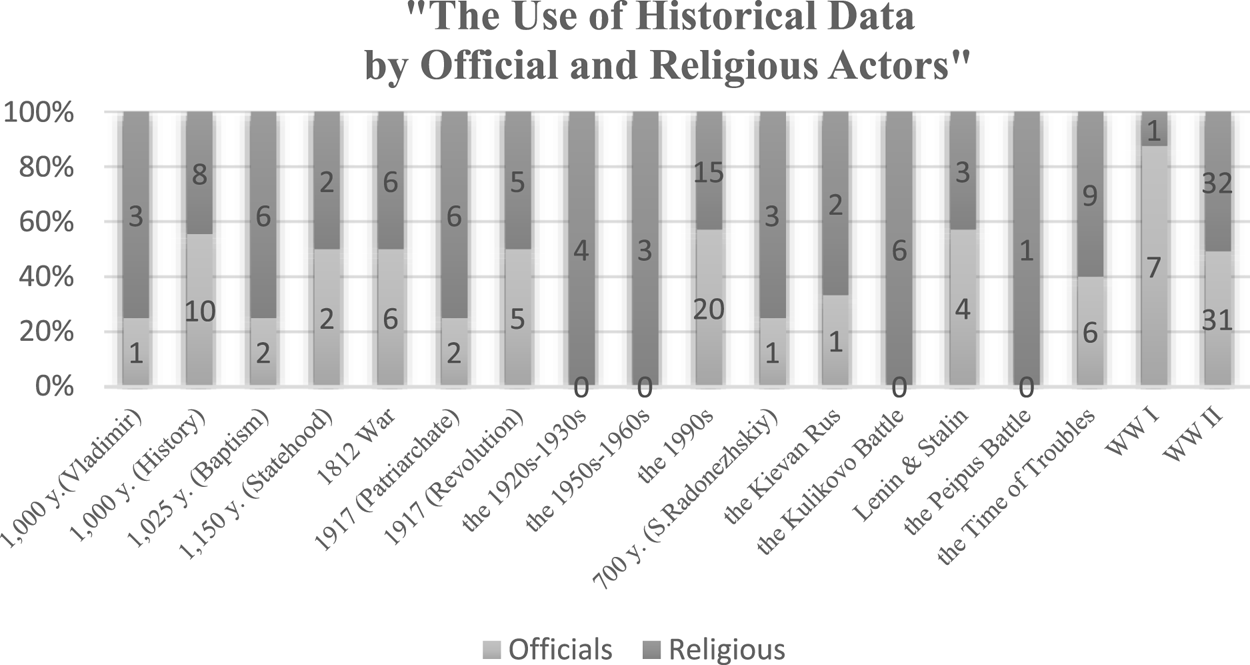

Figure 2 demonstrates that both types of actors (official and religious) draw from similar (but not identical) historical periods for patriotic inspiration. The most frequently mentioned periods are the Second World War, the 1990s, the one thousand years of Russian history and the Time of Troubles, with the Second World War being particularly frequently used as a subject.Footnote 9

Figure 2. The use of historical data by official and religious actors

Source: Calculated by the authors from the data retrieved from http://www.patriarchia.ru and http://www.kremlin.ru.

The memory of World War II is clearly the keystone of any influential historical narrative in today's Russia, and also in the discourse of the Patriarchs, this memory is a “strong bond” which unifies the peoples of the entire former Soviet Union (Kirill Reference Kirill2010c). In the Church's discourse, World War II gains an additional importance as it was the time when the two noblest forms of Orthodox patriotism—the transcendental and the secular—reached their highest point as the people were unified by their “love for the Motherland and the Orthodox faith” (Alexiy 2005d). The Church gives these events yet another twist, however, which differentiates its interpretation from the interpretation of the political authorities: for the leading Russian politicians, it was the entire Soviet people who saved Europe from Nazism (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2009a; Reference Medvedev2010); the Church, on the other hand, often ascribes the victory to the Russian people only (e.g., Kirill Reference Kirill2010d).

THE MILITARIZED ORTHODOX PATRIOTISM

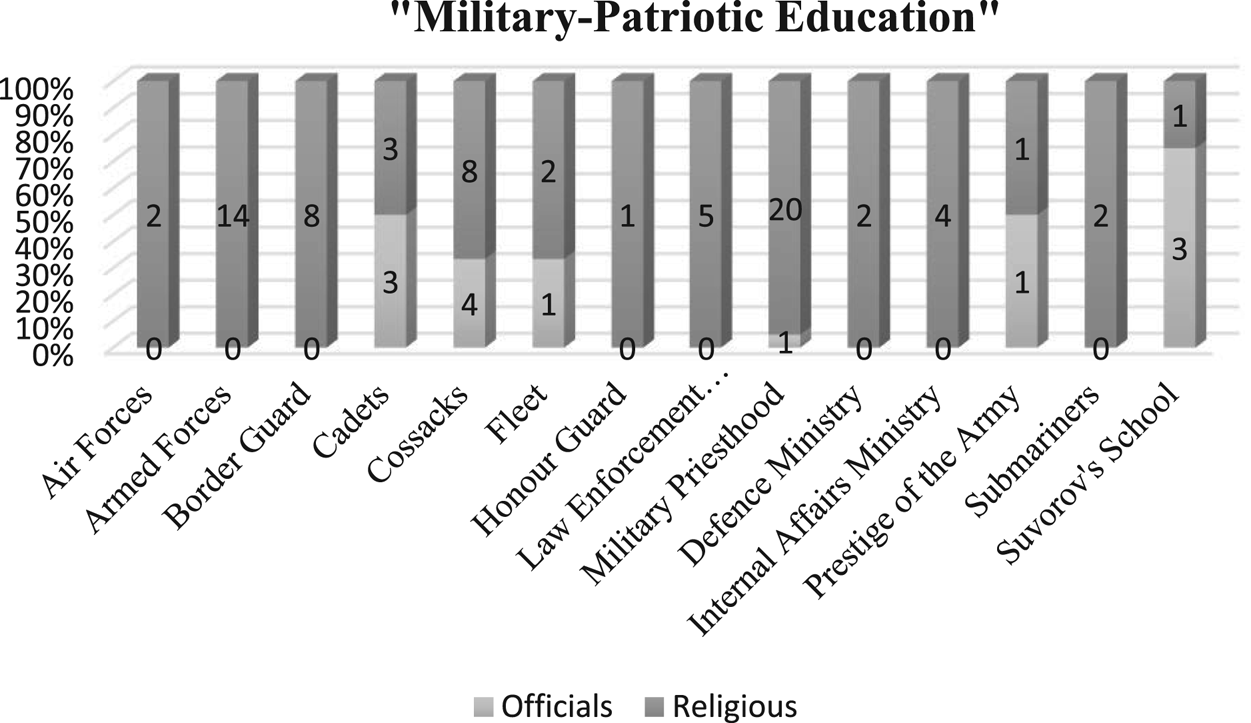

A specific but increasingly important feature of the Church's approach to the process of the collective memory building and patriotic education is its focus on the military. This trait is also shared by the patriotic agenda of the state, as was explored by Marlène Laruelle, who argues that the state patriotic agenda is based on three pillars, which are “the rehabilitation of fatherland symbols and institutionalized historical memory, the instrumentalization of Orthodoxy for symbolic capital, and the development of a militarized patriotism based on Soviet nostalgia” (Reference Laruelle2009, 154). Even though the militarization of Russia's foreign policy has been particularly strong in the last years, the Church already started to focus on the military in the 1990s. Under the slogan “The Army is always spiritual” (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997), the Church started to demand greater access to the military, such as more places for the clergy in the Russian Armed Forces (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006c; Reference Alexiy2006f). Its major political success was the introduction of the institute of the military priesthood in the Armed Forces [военное духовенство] in 2009. Already in 2011, Kirill reported that “…the Church's clergy got 240 places in the Army” (Reference Kirill2011b). Besides the military priesthood, the Church also formalized its cooperation with almost all the militarily oriented ministries: the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Internal Affairs as well as the Federal Border Service (cf. Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997).

As the state-propelled, militarization of the patriotic education has been accelerating, the Church continued to prioritize military patriotism for the laity (Alexiy Reference Alexiy1997; Reference Alexiy2004; Reference Alexiy2005g; Kirill Reference Kirill2015a; Reference Kirill2016a). The argumentation strategy in the justification of this militarization of the believers starts with the claim that the Church has always blessed the Christians who fight in a “just war” (cf. Mikhail Suslov's “sanctified” patriotism [Reference Suslov2014, 73]), which directly translates, according to the Patriarchs, to the obligation of Christians to fight for the Motherland (Alexiy 2005d; 2005f; Kirill Reference Kirill2008b); they add that “the believer sacrifices their life more easily than the non-believer, as he [the believer] knows that human life is not going to end with the end of this life” (Kirill Reference Kirill2011d).

In the second step, the concept of just war is entirely conflated with the defense of the Motherland, and the Motherland is then identified with Russia, but also Russia's military campaigns abroad. For example, the activity of the Russian combatants in Syria was described by Kirill as a “historical mission” (RIA Novosti 2018) and that war as just and defensive (Rossiia 24 2016). Interestingly, the Church leaders allude to the patriotic feelings of Russia's Armed Forces even more frequently than the Russian Presidents (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Military-patriotic education

Source: Calculated by the authors from the data retrieved from http://www.patriarchia.ru and http://www.kremlin.ru.

Alexiy II often underlined the importance of peaceful resolution of conflicts: “The Church never blessed fratricidal conflicts, no matter under which slogans, political, nationalistic or religious, they had been hiding” (Alexiy Reference Alexiy2006b). However, with the coming of Kirill, the attitude changed dramatically, and the pacifist undertones entirely disappeared and were replaced by the focus on the concept of the just war, i.e., fighting for the Motherland. Kirill's arguments are often based on a comparison of Russia with the West. As the West lives in the post-Christian era (Kirill Reference Kirill2016b), people there are obsessed with personal wealth but ignore the moral foundations of the society. Russia, on the other hand, has so far not been poisoned by materialism, but it has to remain vigilant so its people do not start to rot under the burden of their wealth, becoming “walking dead” (Kirill Reference Kirill2011c). In other words, Russia has to be protected from the Western amorality so that it would remain a country of true faith—again, the protection of Russia in this regard is a kind of just war too.

Finally, the Church leaders are particularly fond of the Cossacks, who are seen as embodiments of true Orthodox patriotism (Kirill Reference Kirill2009f; Reference Kirill2010b; Reference Kirill2010h). While the Cossacks are often regarded as the most radical military elements in Russia, as they have fought in Transnistria and the Chechen Wars, but also in the current war in the Donbas, for Kirill, “there is no single Cossack who is not a patriot” (Kirill Reference Kirill2010h).

CONCLUSION

In the last 10 years, the ROC has developed into an exceptionally active political actor, exerting a vast influence over the Russian society. The process, from the Church's refusal to get involved in politics early on under Patriarch Alexiy to the close cooperation between the Russian state and the Church, was not linear, but the result is unequivocal. The Church has become one of the strongest supporters of the Russian state and its policies, depicting the current rulers of Russia as the protectors of the country from enemies both within and without.

At the same time, the Church has developed its own account of Russia's history as well as its own connection to the current events. In this account, Russia is embattled and threatened both militarily and culturally, and it is only natural that the country needs to protect itself. The concept of the just war, propped up by historical parallels with the Time of Troubles, the Napoleonic Wars, and, most importantly, the Second World War, is re-interpreted by the Church as a war to protect the Motherland. Strikingly, the protection is defined rather broadly, as it includes both a cultural defense and military measures, including military activities abroad.

The duality of the military and cultural threats to Russia is mirrored in the Church's intense focus on patriotic education, where the Church again sees itself as the main vehicle for the education of the masses in love for God and love for the country. A by-product of this strategy which has gained a life of its own is the ever-increasing militarization of patriotism, in which the Church is intensely engaged. The frequent praise of the Cossacks, with their history of militarism and their current involvement in a number of conflicts with Russia's neighbors, is a case in point. But the Church's strategy is even more comprehensive, as it also includes many other elements such as changes in the school curricula, the active work of military chaplains as well as the overall glorification of self-sacrifice.

The secularist idea of the strict separation of the Church and the State has never been particularly influential in Russia. However, the present convergence between the Church and the State which has emerged from the current reconstitution of the Russian historical memory posits the two as the key defenders of the Orthodoxy and the Motherland. If the thinkers of post-secularism in the West talk about the gradually increasing visibility of religious agents in the public sphere, in the Russian case, the Church has already become the most vocal voice in the public arena, with a growing influence over Russian legislation, education, and culture as well as the shaping of the Russian historical memory.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The theoretical part and the research design of this article were developed and financed by the research grant “Geopolitics of the Catholic Church” (Czech Grant Agency, SGA0201900001, contract number 19-10969S), corresponding to Petr Kratochvíl's 50% author contribution.