Young men and women differ in their porn use habits.Footnote †Footnote 1 Men start using porn at an earlier age than women (Sinković, Štulhofer, & Božić, Reference Sinković, Štulhofer and Božić2013), watch porn more often than women (Petersen & Hyde, Reference Petersen and Hyde2010), and prefer hardcore over softcore videos (Hald, Reference Hald2006). In this research, we further investigated porn-related gender differences by examining whether young men and women also differ in the relation between porn use and sexual performance.

Sexual performance can be studied based on different conceptualizations and operationalizations depending on the perspective taken. In this research, we distinguished among three sexual performance outcomes: (i) sexual self-competence (the sense of being sexually capable; Snell, Reference Snell, Fisher, Davis, Yarber and Davis1998), (ii) sexual functioning (the degree of desire, arousal, erection/lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction during sexual activities; Kalmbach, Ciesla, Janata, & Kingsberg, Reference Kalmbach, Ciesla, Janata and Kingsberg2015), and (iii) partner sexual satisfaction (the quality of the sexual exchange/experience, and arguably the least biased measure of sexual performance; Štulhofer, Buško, & Brouillard, Reference Štulhofer, Buško and Brouillard2010b).

The research on the relations between the frequency of porn use and these three outcomes has shown mixed results (for narrative and systematic reviews, see Fisher & Kohut, Reference Fisher and Kohut2017; Leonhardt, Spencer, Butler, & Theobald, Reference Leonhardt, Spencer, Butler and Theobald2019; Wright & Tokunaga, Reference Wright and Tokunaga2018). Such relations seem to be particularly equivocal in early adulthood, which is a critical time in the discovery of sexuality (Wallmyr & Welin, Reference Wallmyr and Welin2006). On the one hand, some authors have reported that porn use was associated with sexual performance concerns among young people, presumably because porn use sets unattainable standards of sexual comparison [e.g. not lasting as long as actors (for men) or not experiencing an orgasm as easily as actresses (for women); Goldsmith, Dunkley, Dang, & Gorzalka, Reference Goldsmith, Dunkley, Dang and Gorzalka2017]. It is often thought that frequent porn use distorts beliefs about sexuality (Manning, Reference Manning2006; Ward, Reference Ward2016) and represents a threat to sexual self-competence, particularly for men (Morrison, Ellis, Morrison, Bearden, & Harriman, Reference Morrison, Ellis, Morrison, Bearden and Harriman2007). Accordingly, highly publicized authors have argued that porn was one of the root causes of ‘escalating, morphing sexual tastes, a range of sexual dysfunctions, and loss of attraction to real partners’ (Wilson, Reference Wilson2014; for other popular books, see Dines, Reference Dines2010; Zimbardo & Coulombe, Reference Zimbardo and Coulombe2015).

On the other hand, some authors have warned against harm-focused research approaches that seek to demonstrate the adverse effects of porn use while disregarding its neutral or potentially beneficial effects (Campbell & Kohut, Reference Campbell and Kohut2017). In fact, porn not only raises sexual performance concerns among young people but can also be used to acquire knowledge about certain sexual techniques [e.g. how to perform cunnilingus (for heterosexual men or lesbians) or fellatio (for heterosexual women or gay men); Peter & Valkenburg, Reference Peter and Valkenburg2016]. It was demonstrated that frequent porn use could actually broaden one's sexual horizons (Häggström-Nordin, Tydén, Hanson, & Larsson, Reference Häggström-Nordin, Tydén, Hanson and Larsson2009; Weinberg, Williams, Kleiner, & Irizarry, Reference Weinberg, Williams, Kleiner and Irizarry2010) and foster sexual self-competence (Morrison, Harriman, Morrison, Bearden, & Ellis, Reference Morrison, Harriman, Morrison, Bearden and Ellis2004). Accordingly, some scholars have reported that the alleged negative effects of porn use on sexual quality or functioning lack robustness (Grubbs & Gola, Reference Grubbs and Gola2019; Landripet & Štulhofer, Reference Landripet and Štulhofer2015) and that these effects could sometimes be positive (Bőthe et al., Reference Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Griffiths, Potenza, Orosz and Demetrovics2021). It has even been suggested that porn use could serve as a therapeutic tool to treat hypoactive sexual disorder (Mollaioli, Sansone, Romanelli, & Jannini, Reference Mollaioli, Sansone, Romanelli and Jannini2018) or help couples suffering from sexual dissatisfaction (Watson & Smith, Reference Watson and Smith2012).

Authors have suggested many possible moderators to account for the inconsistency in the relation between porn use and sexual performance-related outcomes (e.g. attitude toward pornography, context of porn use, relationship status; Leonhardt et al., Reference Leonhardt, Spencer, Butler and Theobald2019; Willoughby, Leonhardt, & Augustus, Reference Willoughby, Leonhardt and Augustus2020). In this research, we drew on meta-analysis and/or literature reviews suggesting that one of the key moderators might be gender (Vaillancourt-Morel, Daspe, Charbonneau-Lefebvre, Bosisio, & Bergeron, Reference Vaillancourt-Morel, Daspe, Charbonneau-Lefebvre, Bosisio and Bergeron2019; Wright, Tokunaga, Kraus, & Klann, Reference Wright, Tokunaga, Kraus and Klann2017). Because men and women hold different sexual preferences and gender roles (Petersen & Hyde, Reference Petersen and Hyde2010; Stewart-Williams & Thomas, Reference Stewart-Williams and Thomas2013), they tend to interpret, internalize, and apply different sexual scripts from porn (heuristics that tell them how to behave sexually; Wright, Reference Wright2011), which could alter the relation between porn use and their sexual performance. To give a concrete example, because men have a higher sex drive than women, they may derive particular sexual guidelines from porn such as cutting foreplay, which may in turn lead to sexual callousness and erosion of relationship intimacy (for relevant research, see Bridges & Morokoff, Reference Bridges and Morokoff2011; Štulhofer, Buško, & Landripet, Reference Štulhofer, Buško and Landripet2010a; see also Wright & Vangeel, Reference Wright and Vangeel2019). In the same vein, men using porn may be more prone to developing sexual performance-related concerns from comparison to the actors and/or feel disappointed in their partner's inability (or lack of desire) to perform the sexual acts portrayed in porn (for relevant research, see Leonhardt & Willoughby, Reference Leonhardt and Willoughby2019; Sun, Bridges, Johnson, & Ezzell, Reference Sun, Bridges, Johnson and Ezzell2016; Wright, Paul, Herbenick, & Tokunaga, Reference Wright, Paul, Herbenick and Tokunaga2021).

Research questions and overview of the study

In this research, we aimed to test whether young men and women differ in terms of the relations between porn use and three sexual performance outcomes: What are the relations of porn use with men's and women's sexual self-competence (RQ1), sexual functioning (RQ2), and partner-reported sexual satisfaction (RQ3)?

Existing studies have tested similar moderation effects but have been limited in the sense that most of them had small sample sizes, relied on a cross-sectional design, and/or focused on one single subcomponent of sexual performance (e.g. Bridges & Morokoff, Reference Bridges and Morokoff2011; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Ellis, Morrison, Bearden and Harriman2007; Poulsen, Busby, & Galovan, Reference Poulsen, Busby and Galovan2013). To overcome this type of limitation, we recruited a sample of more than 100 000 participants, used a three-wave longitudinal design, and measured a comprehensive set of sexual performance outcomes. To build such a large sample, we collaborated with Mathieu Sommet, one of the most popular French YouTubers at the time of the research (with 1.6+ million subscribers). Mathieu posted an online video that invited his audience to complete our questionnaire, and voluntary participants were sent a similar follow-up questionnaire approximately one and then two years later. Although our sample was not nationally representative, Mathieu's audience had two key advantages as a target population: (i) youthfulness (his viewers were at a pivotal moment in their sexual development) and (ii) hyper-connectedness (his viewers had easy access to online porn). Note that Mathieu's then-channel ‘Salut Les Geeks’ (SLG) was a rather mainstream comedy channel (revolving around reviewing viral videos) that had nothing to do with sexual health. The deidentified data set, full materials (annotated questionnaires and codebooks), and Stata scripts to reproduce the findings are available on https://osf.io/nfbcp/.

The SLG study

Method

Ethics information

This study received approval from the Ethics Board of the University of Geneva.

Procedure and participants

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and sexual characteristics for wave 1 (online Supplementary Table S1 presents similar information for waves 1–3).

Table 1. Description of the sociodemographic and sexual characteristics of the wave 1 sample

a Only nonvirgins were considered; bonly participating partners were considered.

Data collection

Wave 1

In June 2015, the French YouTuber Mathieu Sommet posted an online video that invited his followers to complete a questionnaire entitled ‘Sexual profile of adults’.Footnote 2 A total of 171 462 participants (18+ year-olds) started the questionnaire, and 101 572 finished it. At the end of the questionnaire, the participants who were in relationships were asked to provide their own and their partner's birth dates (to identify and pair participating partners without using their names) and to forward the questionnaire to their partners.

Wave 2

Approximately one year later, the 47 575 participants who agreed to leave their email addresses at the end of the wave 1 questionnaire were sent a very similar follow-up questionnaire (response rate: 50.64%). Another year later, participants were again invited to complete the same follow-up questionnaire (response rate: 70.65%)

Samples/subsamples

For this research, we used the following (sub)samples:

(i) The wave 1 sample comprised 105 453 participants (61.45% men; 38.55% women) who provided complete data on our main predictor (the frequency of porn use) and first outcome of interest (sexual self-competence) for the first wave of data collection.

(ii) The waves 1–3 sample comprised 21 898 participants (52.11% men; 47.89% women) who provided complete data on the same variables for at least two of the three waves of data collection. We excluded participants (2.80%) who reported inconsistent responses to the gender question (e.g. ‘woman’ in wave 1 and ‘man’ in wave 2).

(iii) The wave 1 couple subsample comprised 8608 participating heterosexual partners whose sexual satisfaction information could be linked to one another. Nonheterosexual couples were excluded a priori because RQ3 applied to the effect of heteronormative porn on heterosexual romantic relationships.Footnote 3 However, when these participants were included, the conclusions from the main analysis remained the same.

(iv) The waves 1–3 couple subsample comprised 1002 participating heterosexual partners whose sexual satisfaction information could be linked to one another for at least two of the three waves of data collection. We used the same exclusion criteria used in the wave 1 couple subsample.

Variables

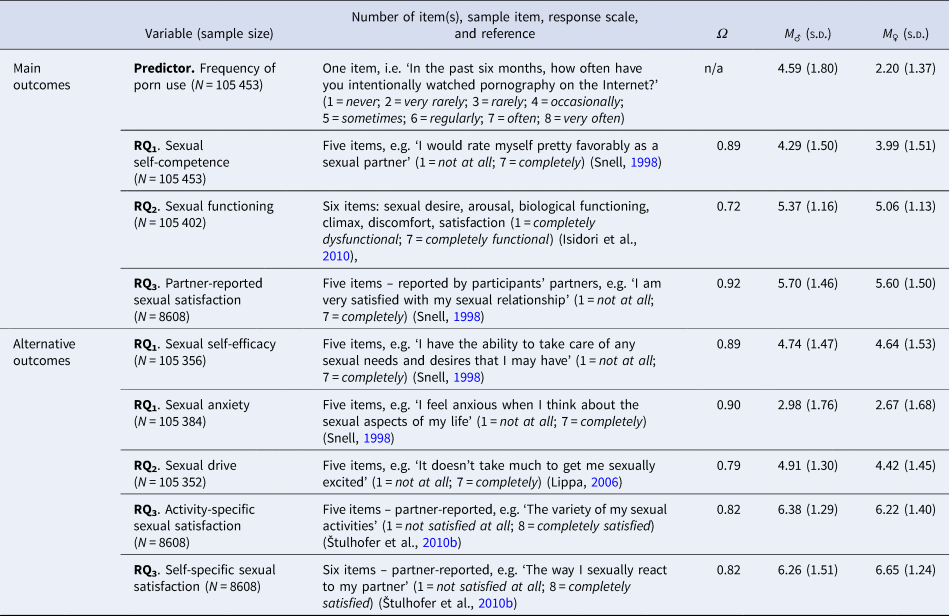

Table 2 presents the sample size, reliability, and descriptive statistics by gender for each variable. The items of each multi-item measure were averaged. Unless otherwise noted, all of the response scales ranged from 1 = not at all to 7 = completely.

Table 2. Description of the focal predictor, main outcomes, and alternative outcomes (robustness checks), along with sample size, reliability estimate (McDonalds' Ω), and descriptive statistics by gender

RQ1–3. Frequency of porn use. We used the following item: ‘In the past six months, how often have you intentionally watched pornography on the Internet?’ (1 = never; 8 = very often). The item was not displayed for the participants who reported having never intentionally watched porn [7.83% of the sample; for these participants, the variable was recoded as ‘1’ (never)]. We followed the current recommendations (Kohut et al., Reference Kohut, Balzarini, Fisher, Grubbs, Campbell and Prause2020; Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck, & Wells, Reference Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck and Wells2012) and provided a definition of porn before presenting the item [‘any sexually explicit material (image/video) […] displaying a man/men's and/or a woman/women's genitalia with the aim of sexual arousal’].Footnote 4

RQ1. Sexual self-competence. We used the sexual self-competence measure from the Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (MSSCQ; Snell, Reference Snell, Fisher, Davis, Yarber and Davis1998; five items, e.g. ‘I am a pretty good sexual partner’).

RQ2. Sexual functioning. We adapted the items of the Sexual Function Index (Isidori et al., Reference Isidori, Pozza, Esposito, Ciotola, Giugliano, Morano and Jannini2010), a six-item clinical tool that assesses sexual desire, sexual arousal, biological functioning (erection/lubrication), sexual climax, sexual satisfaction, and vaginal discomfort (for women) during sexual activities (for the exact wording of the items for men and women, see online Supplementary Table S3).

RQ3. Partner-reported sexual satisfaction. We used the sexual satisfaction measure from the MSSCQ (five items, e.g. ‘I am very satisfied with my sexual relationship’). For each wave, this variable was attached to the participating partner to create the partner-reported sexual satisfaction measure.

Results

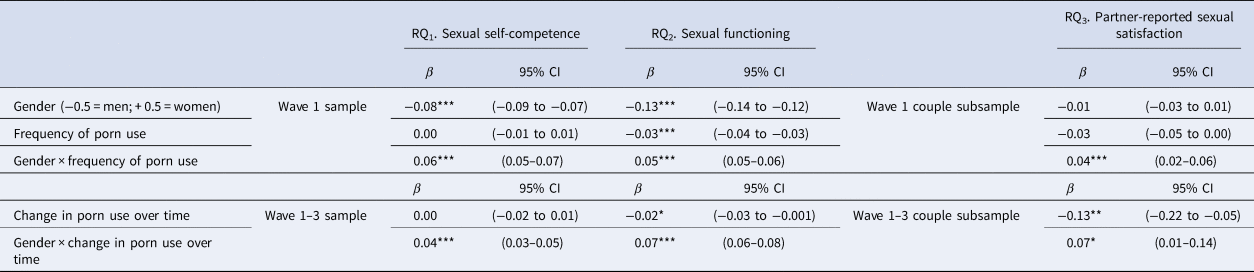

The full results can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Standardized coefficients and 95% CIs of the cluster-adjusted regression models testing the effects of frequency of porn use as a function of gender (wave 1) and the fixed-effects panel regression models testing the effects of change in the frequency of porn use over time as a function of gender (waves 1–3) on sexual self-competence (RQ1), sexual functioning (RQ2), and partner-reported sexual satisfaction (RQ3)

Notes: All variables were standardized; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Overview of the two-step analytical strategy

Step #1. Cross-sectional analysis (between-participants estimates)

As a first step, we used the wave 1 data and built a regression model with standard errors (s.e.) adjusted for dyadic clustering (to address the issue of the interdependence of the residuals within couples). For each research question, we regressed our focal outcome Yi on gender, the frequency of porn use, and their interaction (Eq. 1):

where i = 1, 2, …, N (participants) and ei is the error term.

Step #2. Longitudinal analysis (within-participants estimates)

The cross-sectional nature of the above analysis limited our ability to approach causality. In particular, the between-participants effect of porn use could be contaminated by unobserved heterogeneity, such as time-constant sexual preferences. Thus, as a second step, we used the waves 1–3 data and built a fixed-effects panel regression model that tested the effect of the change in the frequency of porn use over time as a function of gender. Fixed-effects panel regression is very popular in sociology or econometrics, but it has only recently received attention within psychology (McNeish & Kelley, Reference McNeish and Kelley2019). This type of regression allows one to discard all observed and unobserved time-constant individual characteristics (eliminating all potential between-participant confounders) and obtain unbiased estimates of the pooled within-participant effects over time (Allison, Reference Allison2009). Fixed-effects panel regression has been described as ‘one of the most powerful tools for studying causal processes using nonexperimental data’ (Osgood, Reference Osgood, Piquero and Weisburd2010, p. 380) since causality is often inferred from the within-participant effects (however, for a discussion of its limitations, see Hill, Davis, Roos, & French, Reference Hill, Davis, Roos and French2020). In our case, for each research question, we regressed the focal outcome Yit on the frequency of porn use and its interaction with gender (Eq. 2).Footnote 5

where t = 1, 2, 3 [waves], αi is participant fixed effects, and uit is the error term.

RQ1: Porn use and men's and women's sexual self-competence

To test RQ1, we used sexual self-competence as the focal outcome.

Cross-sectional analysis

Our wave 1 sample-based cluster-adjusted regression model revealed that the relation between the frequency of porn use and sexual self-competence differed between men and women: For men, the higher the frequency of porn use, the lower the sexual self-competence, β = −0.06 (−0.07 to −0.05), p < 0.001 (numbers in round brackets represent 95% CIs); for women, the higher the frequency of porn use, the higher the sexual self-competence, β = 0.09 (0.07–0.11), p < 0.001. Following the current recommendations (Wright, Reference Wright2021a), we repeated this and the subsequent cross-sectional analyses while controlling for the most commonly used sociodemographic and sexual characteristics (age, education, nationality, sexual orientation, number of lifetime sexual partners, relationship status, length of the relationship, frequency of masturbation, frequency of sexual intercourse, knowledge about sexuality, and social desirability), and the conclusions remained the same (online Supplementary Table S5).

Longitudinal analysis

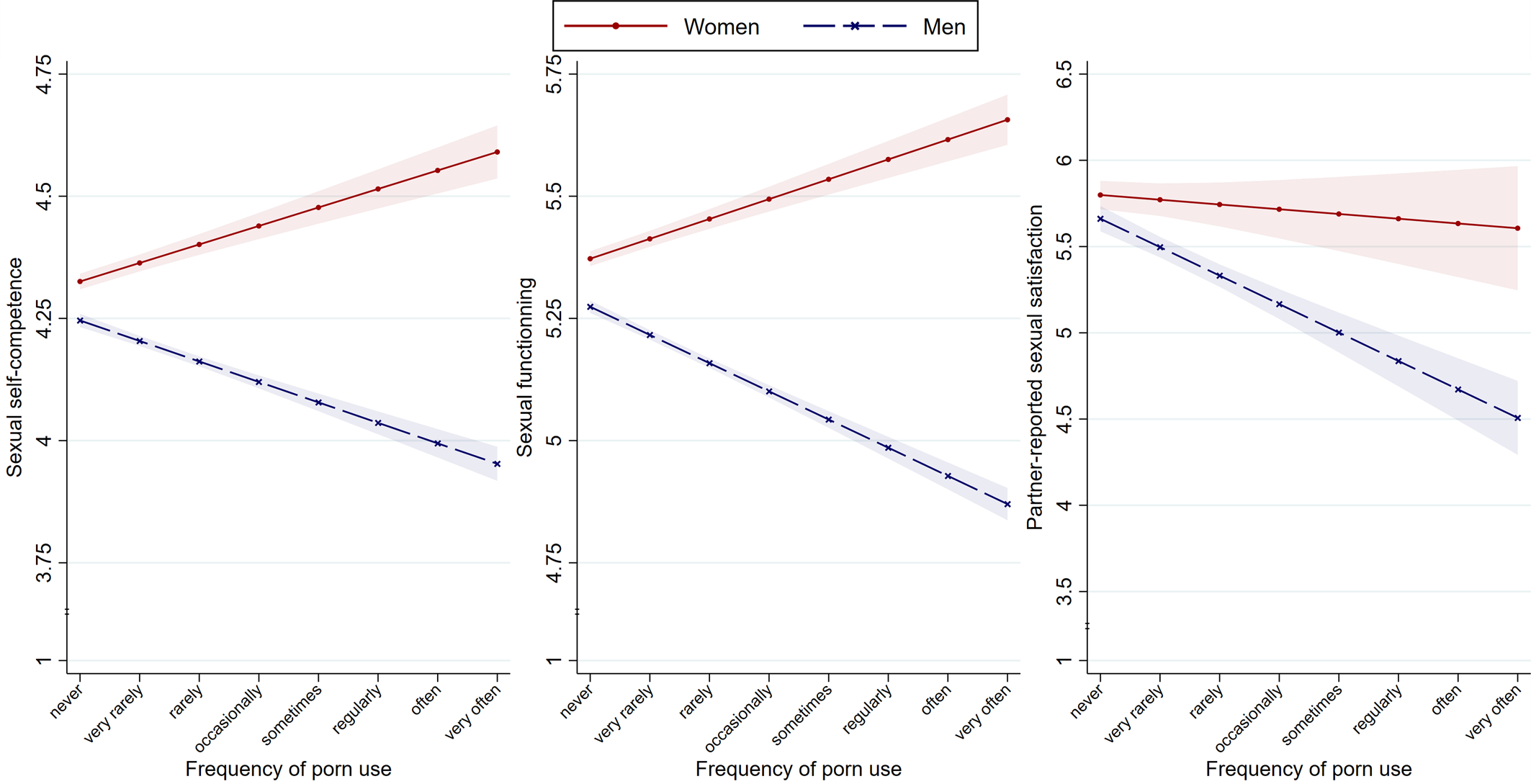

Our waves 1–3 sample-based fixed-effects panel regression model revealed that the effect of the change in the frequency of porn use on sexual self-competence differed between men and women: For men, an increase in the frequency of porn use over time was associated with a reduction in sexual self-competence, β = −0.08 (−0.11 to −0.06), p < 0.001; for women, an increase in the frequency of porn use over time was associated with an increase in sexual self-competence, β = 0.08 (0.05–0.11), p < 0.001 (Fig. 1, left panel). We repeated this and the subsequent longitudinal analyses while controlling for (time-varying) sociodemographic and sexual characteristics (relationship status, frequency of masturbation, frequency of sexual intercourse, and knowledge about sexuality) and period effects (wave dummies), and the conclusions remained the same (online Supplementary Table S6). Finally, given that the curvilinear effects of porn use on sexual outcomes had been documented (e.g. Wright, Steffen, & Sun, Reference Wright, Steffen and Sun2019), we repeated all main analyses while including the quadratic effect of frequency of porn use; the results – which are inconclusive – are presented in online Supplementary Table S7.

Fig. 1. RQ1–3. Longitudinal effects of the frequency of porn use on sexual self-competence (RQ1, left panel), sexual functioning (RQ2, middle panel), and partner-reported sexual satisfaction in heterosexual couples (RQ3, right panel) among men and women. Notes: Shaded areas represent the s.e. of the means.

Robustness checks.

We performed two series of robustness checks.

Alternative outcomes

First, we repeated the main analyses using two alternative outcomes that were closely related to sexual self-competence, specifically, sexual self-efficacy and sexual anxiety [the full description of the measures is presented in the online Supplementary Materials, along with a PCA showing that the items loaded on different components (online Supplementary Table S2)]. The interactions were the same as in the main analysis. Both the frequency of porn use (wave 1) and the change in porn use over time (waves 1–3) had negative effects on men's sexual self-efficacy (whereas the effects were positive for women) and negative effects on men's sexual anxiety (whereas the effects were weaker or null for women; online Supplementary Table S8).

Alternative estimator

Second, we repeated the main longitudinal analysis using an alternative analytical approach: first-difference regression (Allison, Reference Allison2009). Such an approach allows for the estimation of the change between two consecutive waves (rather than the overall within-participant change). The conclusions remained the same, increasing the plausibility (but not the certainty) that the findings are causal (online Supplementary Table S9). In this and the subsequent analyses, the conclusions of the two series of robustness checks remained similar when including our sets of control variables.

RQ2: Porn use and men's and women's sexual self-functioning

To test RQ2, we used sexual functioning as the focal outcome.

Cross-sectional analysis

Our wave 1 sample-based cluster-adjusted regression model revealed that the relation between the frequency of porn use and sexual functioning differed between men and women: For men, the higher the frequency of porn use, the lower the sexual functioning, β = −0.09 (−0.09 to −0.08), p < 0.001; for women, the higher the frequency of porn use, the higher the sexual functioning, β = 0.05 (0.03–0.06), p < 0.001.

Longitudinal analysis

Our waves 1–3 sample-based fixed-effects panel regression model revealed that the effect of the change in the frequency of porn use on sexual functioning differed between men and women: For men, an increase in the frequency of porn use over time was associated with a reduction in sexual functioning, β = −0.10 (−0.13 to −0.08), p < 0.001; for women, the frequency of porn use over time was associated with an increase in sexual functioning, β = 0.07 (0.05–0.10), p < 0.001 (Fig. 1, middle panel).

Robustness checks

As in RQ1, we performed two series of robustness checks.

Alternative outcome

First, we repeated the main analyses using an alternative outcome that was closely related to sexual functioning, specifically, sexual drive (the full description of the measure is presented in online Supplementary Materials). The interaction was the same as in the main analysis. Both the frequency of porn use (wave 1) and the change in porn use over time (waves 1–3) had stronger positive effects on women's sexual drive than on men's sexual drive (online Supplementary Table S8).

Alternative estimator

Second, we repeated the main longitudinal analysis using our alternative estimator (first-difference regression). Again, the conclusions remained the same, increasing the plausibility (but not the certainty) that the findings are causal (online Supplementary Table S9).

RQ3: Porn use and men's and women's partner-reported sexual satisfaction

To test RQ3, we used partner-reported sexual satisfaction as the focal outcome.

Cross-sectional analysis

Our wave 1 couple subsample-based cluster-adjusted regression model revealed that the relation between the frequency of porn use and partner-reported sexual satisfaction differed between men and women: For men, the higher the frequency of porn use, the lower their partner-reported sexual satisfaction, β = −0.08 (−0.10 to −0.04), p < 0.001; for women, the effect was not different from zero, β = 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.07), p = 0.272.

Longitudinal analysis

Our waves 1–3 couple subsample-based fixed-effects panel regression model revealed that the effect of the change in the frequency of porn use on partner-reported sexual satisfaction differed between men and women: For men, an increase in the frequency of porn use over time was associated with a reduction in their partner-reported sexual satisfaction, β = −0.23 (−0.32 to −0.13), p < 0.001; for women, the effect was not different from zero, β = −0.04 (−0.17 to 0.10), p = 0.587 (Fig. 1, right panel).

Robustness checks

As in RQs1–2, we performed two series of robustness checks.

Alternative outcomes

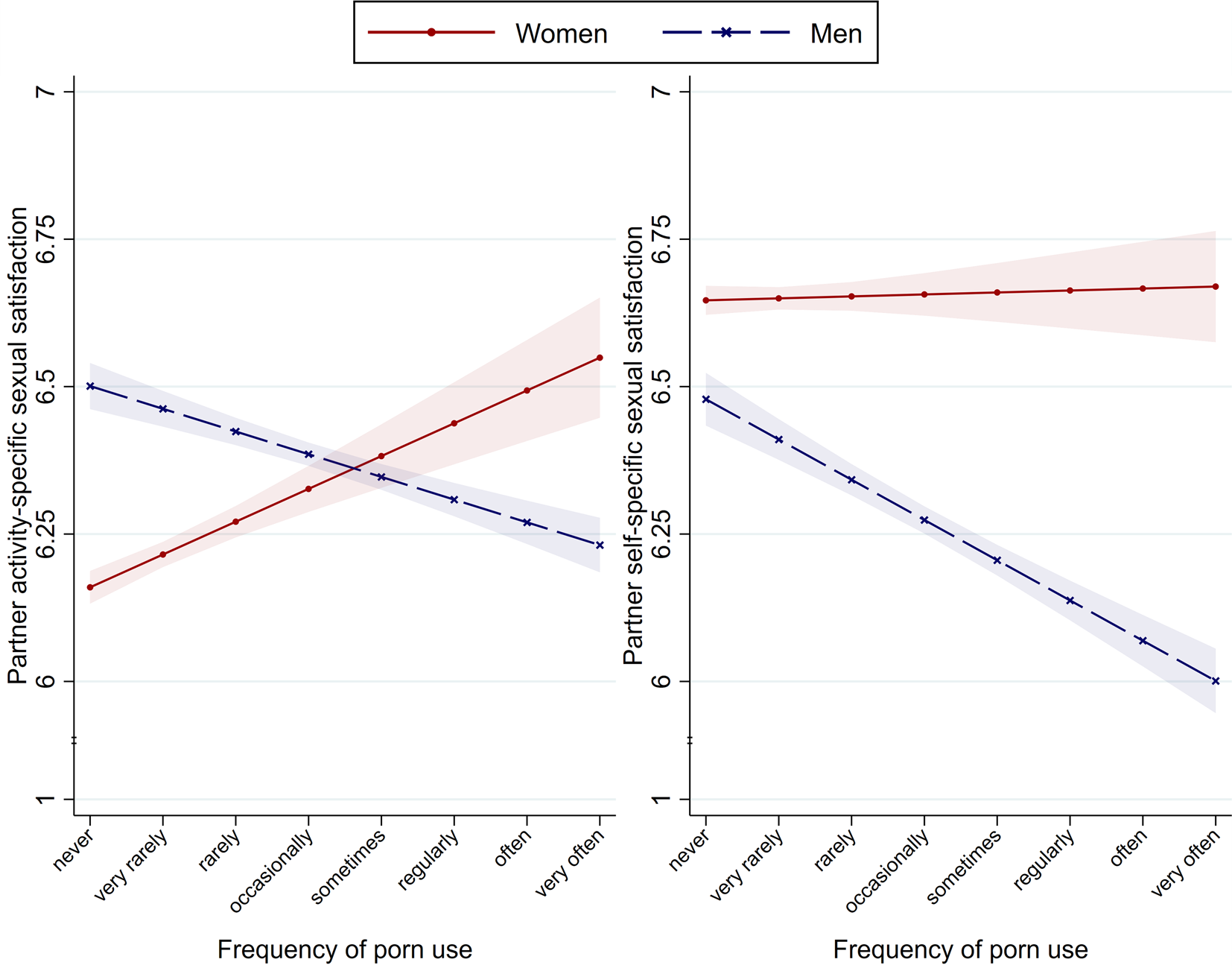

First, we repeated the main analyses using two alternative outcomes that indicate two subdimensions of partner-reported sexual satisfaction, specifically, partner activity-specific sexual satisfaction (the quality of the sexual exchange) and partner self-specific (the quality of the personal sexual experience) sexual satisfaction [the full description of the measure is presented in the online Supplementary Materials, along with a PCA showing that the subdimension items loaded on different components (online Supplementary Table S4)]. In the wave 1 couple subsample, the frequency of porn use had a negative effect on men's partners' activity- and self-specific sexual satisfaction, whereas it had (i) a positive effect on women's partners' activity-specific sexual satisfaction and (ii) a null effect on women's partners' self-specific sexual satisfaction (Fig. 2). However, in the waves 1–3 couple subsample, we did not observe any significant interactions (online Supplementary Table S8).

Fig. 2. RQ3. Relation between the frequency of porn use and partner activity-specific (left panel) and self-specific (right panel) sexual satisfaction in heterosexual couples. Notes: Shaded areas represent the s.e. of the means.

Alternative estimator

Second, returning to our main outcome, we repeated the main longitudinal analyses using our alternative analytical approach (first-difference regression). Again, the conclusions remained the same, increasing the plausibility (but not the certainty) that the findings are causal (online Supplementary Table S9).

Supplementary exploratory analysis

We conducted exploratory analysis testing the idea that porn use could predict couple break ups; the results, which suggest that for women (but not for men), an increase in the frequency of porn use over time is associated with a decrease in the odds of a couple's break up, are presented in online Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

The present research used a large-scale three-wave longitudinal sample to produce two robust sets of findings. For men, porn use is associated with lower sexual performance (lower sexual self-competence, sexual functioning, and partner-reported sexual satisfaction), whereas for women, porn use is associated with higher sexual performance (higher sexual self-competence, sexual functioning, and sexual partner-reported satisfaction – for some aspects).

Interpretation of the findings

These two sets of findings could be interpreted in light of the extant literature. On the one hand, existing research reveals that porn can be a source of sexual inspiration that reinforces sexual permissiveness norms and widens the range of sexual practices and behaviors (Häggström-Nordin et al., Reference Häggström-Nordin, Tydén, Hanson and Larsson2009; Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Williams, Kleiner and Irizarry2010; Wright, Bae, & Funk, Reference Wright, Bae and Funk2013). On the other hand, the existing research reveals that porn can also be a source of threatening upward sexual comparisons, particularly for men (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Paul, Herbenick and Tokunaga2021). For instance, the frequency of porn use predicts penis size dissatisfaction among men (whereas it does not predict genitalia/breast dissatisfaction among women; Cranney, Reference Cranney2015; but see Wright et al., Reference Wright, Tokunaga, Kraus and Klann2017), and it predicts performance-related cognitive distraction during sexual activity among men (but not among women; Goldsmith et al., Reference Goldsmith, Dunkley, Dang and Gorzalka2017). In the same vein, men watch more hardcore/paraphilic porn and less softcore/mainstream porn than women (Hald, Reference Hald2006; Hald & Štulhofer, Reference Hald and Štulhofer2016), which may be associated with different sexual comparison processes and sexual outcomes (Leonhardt & Willoughby, Reference Leonhardt and Willoughby2019). These gender differences are consistent with our results. Among young men, the potentially inspiring nature of porn might be outweighed by its threatening nature: Porn use seemingly contributes to men's doubts about their sexual competence, the deterioration of their sexual functioning, and – in heterosexual couples – their partner-reported satisfaction. In contrast, among young women, the potentially inspiring nature of porn might outweigh its threatening nature: Porn use seemingly contributes to women's feelings of sexual competence, improvement in their sexual functioning, and – in heterosexual couples – some aspects of their partner-reported satisfaction.

Implications

Our results are congruent with ideas sometimes expressed in the literature: (i) reducing porn use could help men to overcome sexual dysfunctions (Kirby, Reference Kirby2021) and (ii) increasing porn use could help women to improve their sexual lives (Mollaioli et al., Reference Mollaioli, Sansone, Romanelli and Jannini2018). However, proponents of these positions should bear in mind that, despite the robustness of our findings, the sex-specific effects of the frequency of porn use often had a low magnitude (0.05 ⩽ βs ⩽ 0.20), although they cannot be considered trivial (the strength of longitudinal associations is mechanically smaller than the strength of cross-sectional associations, and effects as small as β = 0.05 could still have important practical significance; Adachi & Willoughby, Reference Adachi and Willoughby2015). Accordingly, and contrary to what is often suggested in popular books on the psychology of pornography (e.g. Zimbardo & Coulombe, Reference Zimbardo and Coulombe2015), men who face sexual problems and choose to terminate porn use may experience only marginal improvements in their sexual lives (assuming that we can draw causal inferences from our findings); similarly, women who face sexual problems might be well advised not to consider porn use to be a sexual panacea.

Limitations and conclusions

Three important limitations should be acknowledged.

First, >98% of our sample included residents from five French-speaking Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries (FR/BE/CH/LU/CA). Given that the effects of porn use are likely to vary from one cultural context to another (e.g. from nonreligious to religious contexts; Grubbs, Perry, Wilt, & Reid, Reference Grubbs, Perry, Wilt and Reid2019), replications with data from non-WEIRD countries are warranted.

Second, our method of data collection did not enable us to achieve national representativeness. Despite (i) our findings being robust to the inclusion of age, education, nationality, and sexual orientation controls; (ii) most demographics seeming not to be misrepresented (except gender in the wave 1 sample); and (iii) nonrepresentativeness being less of a concern when using within estimators (because individuals act as their own ‘controls’), replications with more representative data are also warranted.

Third, observational data cannot be used to draw causal inferences. However, we believe that causality should be assessed in terms of a ‘continuum of plausibility’ (Dunning, Reference Dunning2008) along which longitudinal evidence is located above cross-sectional evidence (but below experimental evidence; see also Grosz, Rohrer, & Thoemmes, Reference Grosz, Rohrer and Thoemmes2020). In our case, given the consistencies between the results from the fixed-effects (focusing on within-participants change) and first-difference (focused on wave-to-wave change) regressions, we believe that causality is at least plausible. That being said, two alternative explanations – which we regard as less parsimonious in the case of a reversed interaction (for a related discussion, see Wright, Reference Wright2021b) – cannot be formally excluded: (i) the presence of unobserved time-varying confounders (e.g. variations in well-being; see Kohut & Štulhofer, Reference Kohut and Štulhofer2018) and (ii) reciprocal effects (e.g. for men, a decrease in sexual self-competence can cause an increase in porn use, and for women, the reverse could be true).

Despite these limitations, our findings reveal the irony that porn – a male-dominated industry that targets a male-dominated audience – is associated with the erosion of the quality of men's sex lives and the improvement of women's sex lives.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100516X

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by the Swiss Centre of Expertise in Life Course Research. We wish to thank Mathieu Sommet and his audience for having made this study possible, as well as Aleksandar Štulhofer, Annahita Ehsan, Joel Anderson, Frédérique Autin, Anatolia Batruch, Daniel Oesch, Vincent Pillaud, and Michaël Spanu for their helpful comments on our wave 1 questionnaire and/or an earlier version of this manuscript.

Financial support

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open practices statement

The deidentified three-wave data set, full materials (i.e. annotated questionnaires and codebooks), and Stata scripts to reproduce the findings can be found at https://osf.io/nfbcp/.