From both a clinical and a health-economic perspective it is important to distinguish between patients who will benefit sufficiently from short-term psychotherapy and those for whom long-term psychotherapy is required. Data on dose–effect relationships suggest that most patients experiencing acute distress benefit from short-term psychotherapy. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1 Short-term psychotherapy may be defined as a treatment of up to 25 sessions; Reference Gabbard2 applying this definition to the data reported by Kopta et al, about 70% of the patients with acute distress recovered after short-term therapy. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1 For patients with chronic distress, about 60% recovered after 25 sessions. For patients with characterological distress, i.e. personality disorders, the data of Kopta et al suggest that about 40% recovered after 25 sessions. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1 Perry et al estimated the length of treatment necessary for patients with personality disorder to achieve recovery (defined as no longer meeting the full criteria for a personality disorder): according to these estimates, half of such patients would recover after 1.3 years or 92 sessions, and three-quarters after 2.2 years or about 216 sessions. Reference Perry, Banon and Floriana3 Summing up, the majority of patients with acute distress benefit significantly from short-term psychotherapy, whereas for many patients with chronic distress and for the majority of patients with personality disorders, short-term psychotherapy seems not to be sufficient.

Evidence-based treatments for these groups of patients are particularly important. Personality disorders, for example, are not uncommon in both general and clinical populations. They show a high comorbidity with a wide range of Axis I disorders and are significantly associated with functional impairments. Reference Grant, Hasin, Stinson, Dawson, Chou and Ruan4–Reference Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger and Kessler6 Furthermore, personality disorders were found to have a negative prognostic impact on depressive disorders. Reference Gunderson, Morey, Stout, Skodol, Shea and McGlashan7 For this reason, experts recommend not focusing on the depressive disorder but primarily treating the associated personality disorder. Reference Gunderson, Morey, Stout, Skodol, Shea and McGlashan7,Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky and Collins8 Another population for whom short-term treatment may not be sufficient are those with multiple mental disorders. A high proportion of patients in clinical populations have not just one but several mental disorders, and such patients report significantly greater deficits in social and occupational functioning. Reference Olfson, Fireman, Weissman, Leon, Sheehan and Kathol9,Reference Ormel, VonKorff, Ustun, Pini, Korten and Oldehinkel10

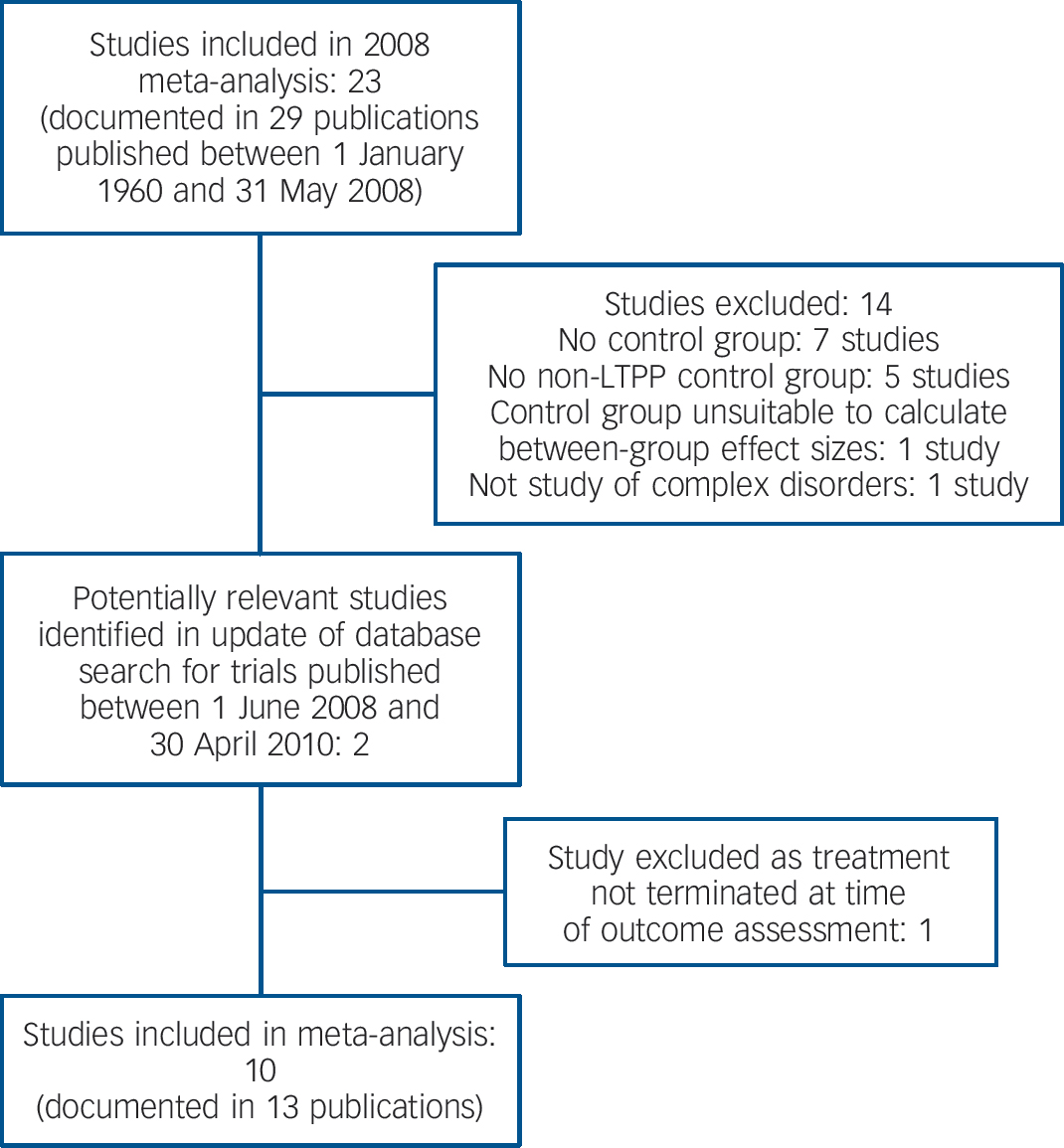

Some data suggest that long-term psychotherapy may be helpful for these groups of patients. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1,Reference Perry, Banon and Floriana3,Reference Bateman and Fonagy11–Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop and Heard14 This is true not only for psychodynamic therapy, but also for psychotherapeutic approaches that are usually short-term, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop and Heard14,Reference Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Spinhoven, van Tilburg, Dirksen and van Asselt15 For long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP), however, strong evidence-based support as yet is lacking. In a recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of LTTP we focused on complex mental disorders which were defined as personality disorders, chronic mental disorders or multiple mental disorders. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 Twenty-three studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Both randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental observational studies were included, allowing us to test for differences between study type. As the number of controlled studies was small, we calculated within-group effect sizes throughout. Large and stable effect sizes were reported for LTPP in patients with these complex disorders. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 For the studies including control groups, we compared the within-group effect sizes between the LTPP conditions and the control conditions: effect sizes for LTPP were significantly larger than those in the control conditions. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 However, comparing within-group effect sizes between treatments uses treatment conditions rather than studies as units of analysis, which may reduce the effect of randomisation. Reference Kriston, Hölzel and Härter17 This may weaken internal validity, but it does not necessarily imply that internal validity is severely impaired. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung18 In order to address this problem we decided to update this meta-analysis, including new studies where available. For the comparison of LTPP and the control conditions between-group effect sizes were assessed, focusing on complex mental disorders as defined above. Our 2008 meta-analysis was criticised by some authors for addressing an ‘unconventionally broad research question’ by including heterogeneous patient populations and comparison conditions. Reference Kriston, Hölzel and Härter17 On the contrary, however, researchers often adopt unnecessarily narrow entry criteria; a broad perspective on meta-analysis covering different patient populations and settings increases the generalisability and usefulness of results. Reference Gotzsche19 If results are not homogeneous, subgroup analysis can be used to examine the reasons. In the 2008 meta-analysis we carried out several subgroup analyses for different diagnostic groups. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 In line with these considerations, our updated meta-analysis focused on complex mental disorders (again defined as personality disorders, chronic mental disorders or multiple mental disorders), addressing the question whether LTPP is superior to shorter or less intensive psychotherapy in treating these disorders.

Method

The procedures followed in our study are consistent with recent guidelines for the reporting of meta-analyses. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman20

Definition of LTPP

Psychodynamic psychotherapy serves as an umbrella concept encompassing treatments that operate on a continuum of supportive–interpretive psychotherapeutic interventions. Reference Gabbard2,Reference Gunderson and Gabbard21–Reference Wallerstein23 Interpretive interventions aim to enhance patients’ insight into repetitive conflicts sustaining their problems; Reference Gabbard2 supportive interventions aim to strengthen abilities that are temporarily inaccessible to patients owing to acute stress (e.g. traumatic events) or have not been sufficiently developed (e.g. impulse control in borderline personality disorder). The establishment of a helping (or therapeutic) alliance is regarded as an important component of supportive interventions. Reference Luborsky22 Transference, defined as the repetition of past experiences in present interpersonal relations, constitutes another important dimension of the therapeutic relationship. In psychodynamic psychotherapy, transference is regarded as a primary source of understanding and therapeutic change. Reference Gabbard2,Reference Luborsky22 The emphasis that psychodynamic psychotherapy puts on the relational aspects of transference is a key technical difference from cognitive–behavioural therapies. Reference Cutler, Goldyne, Markowitz, Devlin and Glick24 The use of more supportive or more interpretive (insight-enhancing) interventions depends on the patient’s needs. The more severely disturbed a patient is or the more acute the problem, the greater is the need for supportive interventions, whereas an emphasis on interpretive approaches is more suitable for less disturbed patients. Reference Luborsky22 Psychodynamic psychotherapy can be carried out either as a short-term (time-limited) or as a long-term open-ended treatment. Open-ended psychotherapy in which treatment duration is not fixed a priori is not identical to unlimited psychotherapy. Reference Luborsky22 Short-term treatments are time-limited, usually lasting between 7 and 24 sessions. Reference Gabbard2 There is no generally accepted standard duration for long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Lamb compiled more than 20 definitions given by experts in the field, Reference Lamb25 ranging from a minimum of 3 months to a maximum of 20 years. In this meta-analysis we included studies that examined psychodynamic psychotherapy lasting for at least 1 year or 50 sessions. This criterion is consistent with the definition given by Crits-Christoph & Barber and other experts in the field. Reference Crits-Christoph, Barber, Ingram and Snyder26

Inclusion criteria and selection of studies

We applied the following inclusion criteria, consistent with recent meta-analyses of psychotherapy: Reference Leichsenring, Rabung and Leibing27

-

(a) studies of psychodynamic therapy meeting the definition given above; Reference Gabbard2,Reference Gunderson and Gabbard21–Reference Wallerstein23

-

(b) psychodynamic therapy lasting for at least 1 year or at least 50 sessions;

-

(c) active treatments applied in the control conditions;

-

(d) prospective studies of LTPP including pre- and post-treatment or follow-up assessments;

-

(e) treatments must have been terminated (no study assessing outcome for ongoing treatments);

-

(f) use of reliable and valid outcome measures;

-

(g) a clearly described sample of patients with ‘complex’ disorders (personality disorders, chronic mental disorders or more than one mental disorder);

-

(h) adult patients (at least 18 years of age);

-

(i) sufficient data to allow determination of between-group effect sizes.

We collected studies of LTPP that were published between January 1960 and April 2010 based on our previous meta-analysis and an updated computerised search of Medline, PsycINFO and Current Contents. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 The following search terms were used: (psychodynamic OR dynamic OR psychoanalytic* OR transference-focused OR self psychology OR psychology of self) AND (therapy OR psychotherapy OR treatment) AND (study OR studies OR trial*) AND (outcome OR result* OR effect* OR change*) AND (psych* OR mental*) AND (rct* OR control* OR compar*). In addition, articles and textbooks were manually searched, and we communicated with authors and experts in the field.

Data extraction

We independently extracted the following information from the articles: author names, publication year, psychiatric disorder treated with LTPP, age and gender of patients, duration of LTPP, number of sessions, type of comparison group, sample size in each group, use of treatment manuals (yes/no), general clinical experience of therapists (years), specific experience with the patient group under study (years), specific training of therapists (yes/no), study design (RCT v. effectiveness), duration of follow-up period and use of psychotropic medication. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Rating was done without masking to treatment condition, since evidence suggests that such masking is unnecessary for meta-analyses. Reference Berlin28 Effect sizes were independently assessed by two raters. Interrater reliability was assessed for the outcome domains in question: overall outcome, target problems, psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning and social functioning. For all areas interrater reliability was high (r≥0.95, P≤0.002). Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16

Assessment of effect sizes and statistical analysis

We assessed effect sizes for target problems, psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning, social functioning and overall outcome. As outcome measures of target problems, we included both patient ratings of target problems and measures referring to the symptoms specific to the patient group under study (e.g. measures of depression in treatment studies of major depressive disorder or a measure of impulsivity for studies examining borderline personality disorder). Reference Battle, Imber, Hoehn-Saric, Nash and Frank29 For psychiatric symptoms we included both broad measures of psychiatric symptoms such as the Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90) and specific measures such as measures of depression or anxiety. Reference Derogatis30 For the assessment of personality functioning, measures of personality characteristics were included (e.g. the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory). Reference Millon31 Social functioning was assessed using the Social Adjustment Scale and similar measures. Reference Weissman and Bothwell32 Whenever a study reported multiple measures for one of the areas of functioning (e.g. target psychiatric symptoms), we assessed the effect size for each measure separately and calculated the mean effect size of these measures within each study. In our previous meta-analysis outcome measures were assigned either to target problems or to psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning or social functioning. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16,Reference Leichsenring, Rabung and Leibing27 In a study of depressive disorders, for example, a reduction in depression could be attributed only to target problems, not to psychiatric symptoms. However, this procedure may artificially narrow the data basis for the estimation of actual therapeutic effects in the respective outcome areas. In order to avoid this problem in this meta-analysis, we first assigned each outcome measure to one (and only one) of the three domains of psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning or social functioning. Overall outcome was assessed by averaging the effect sizes of these three areas. To obtain information about changes in target problems, outcome measures referring to criteria specific to the patient group under study (e.g. measures of depression in depressive disorders), which were in the first step of evaluation assigned to one of the aforementioned three areas, were additionally assigned to the domain of target problems. This means that the results for target problems are not independent of the other three areas, but more realistic estimates of therapeutic effects will be achieved. As a measure of between-group effect size for continuous measures, we calculated Hedges’ d and the associated 95% confidence interval. Reference Hedges and Olkin33 This measure is a variation of Cohen’s d which corrects for bias due to small sample sizes. Reference Hedges and Olkin33 Hedges’ d was calculated by subtracting the mean pre-treatment to post-treatment or follow-up difference of the control condition from the corresponding difference of LTPP, divided by the pooled pre-treatment standard deviation. This quotient was multiplied by a coefficient J correcting for small sample size to obtain Hedges’ d. If a study included more than one LTPP or comparison group, we used the averaged effect sizes of these groups. We aggregated the effect sizes estimates (Hedges’ d) across studies, adopting a random effects model which is more appropriate if the aim is to make inferences beyond the observed sample of studies. Reference Hedges and Vevea34 To obtain a mean effect sizes estimate we used MetaWin version 2.0 for Windows. Reference Rosenberg, Adams and Gurevitch35 If the data necessary to calculate effect sizes were not published in the article, we asked its authors for this information. If necessary, signs were reversed so that a positive effect size always indicated improvement. In order to examine the stability of psychotherapeutic effects, we assessed effect sizes separately for assessments at the termination of therapy and follow-up. If data pertaining to completers and intention-to-treat (ITT) samples were reported, the latter were included. To control for bias related to withdrawal, we additionally carried out ITT analyses. For studies that did not report ITT data we conservatively set the effects for patients who withdrew after randomisation to zero. By this procedure, the effect sizes reported for the completers sample were adjusted for missing ITT data. If a study, for example, reported a pre–post treatment difference of 0.40 for a group of 20 patients who completed the study with 5 patients having withdrawn, we used an adjusted difference of 0.32 (0.40 × 20/25) for the ITT analysis. Tests for heterogeneity were carried out using the Q statistic. Reference Hedges and Olkin33 To assess the degree of heterogeneity, we calculated the I Reference Gabbard2 index. Reference Huedo-Medina, Sanchez-Meca, Botella and Marin-Martinez36 In cases of significant heterogeneity random effect models are more appropriate. Reference Hedges and Vevea34,Reference Quintana and Minami37 To control for publication bias, tests for asymmetry in funnel plots and ‘file drawer’ analyses were performed. Reference Huedo-Medina, Sanchez-Meca, Botella and Marin-Martinez36–Reference Rosenthal39 Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 15.0 and MetaWin version 2.0. Reference Rosenberg, Adams and Gurevitch35,40 Two-tailed tests of significance were carried out for all analyses. The significance level was set to P = 0.05 unless otherwise stated. If more is better, outcome should increase with dosage and duration of treatment. For this analysis we used within-group effect sizes which were calculated for each condition by subtracting the post-treatment mean from the pre-treatment mean and dividing the difference by the pooled pre-treatment standard deviation of the measure. Reference Cohen41,Reference Hedges42 If more than one LTPP condition or more than one control condition was included, we treated them separately in this analysis. Spearman correlations were assessed between within-group effect sizes and both duration of treatment and number of sessions.

Assessment of study quality

According to the inclusion criteria described earlier, we analysed only prospective studies of LTPP in which reliable outcome measures were used, the patient sample was clearly described and data to calculate effect sizes were reported. In addition, the quality of studies was assessed by use of the scale proposed by Jadad et al. Reference Jadad, Moore, Carroll, Jenkinson, Reynolds and Gavaghan43 This scale takes into account whether a study is described as randomised and double-blind, and whether withdrawals and ‘drop-outs’ are itemised. In psychotherapy research, however, studies cannot be double-blind because the participants know or can easily find out which treatment they receive. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 Thus, all studies of psychotherapy would have to be given a score of zero on this item of the Jadad scale. Instead of masking of therapists and patients, the respective requirement in psychotherapy research is that any observer-rated outcome measure is rated by assessors unaware of the treatment condition. Additionally, the patient perspective is of particular importance in psychotherapy. For this reason, outcome is often assessed by self-report instruments. We therefore decided to give a score of one point on this item if outcome was assessed by masked raters or by reliable self-report instruments. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 With this modification, the three items of the Jadad scale were independently rated by us for all studies included; a satisfactory interrater reliability was achieved for the total score of the scale (r = 0.92, P<0.001).

Results

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Reference Bateman and Fonagy11,Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13,Reference Bachar, Latzer, Kreitler and Berry44–Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 For three of these studies we received additional information from the authors. Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13,Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 Levy et al reported additional data on outcome for the study by Clarkin et al. Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13,Reference Levy, Meehan, Kelly, Reynoso, Weber and Clarkin52 In contrast to our 2008 meta-analysis, we now included the supportive treatment of the study by Clarkin et al as a form of LTPP because of its description by Levy et al as a psychodynamic therapy. Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13,Reference Levy, Meehan, Kelly, Reynoso, Weber and Clarkin52 The study by Korner et al used a non-randomised comparison group. Reference Korner, Gerull, Meares and Stevenson50 Meta-analytic results, however, have shown that non-randomised comparison group designs yield comparable – if anything, slightly smaller – effect size estimates to randomised designs. Reference Lipsey and Wilson53 For this reason we included the study by Korner et al. Reference Korner, Gerull, Meares and Stevenson50 In an RCT by Knekt et al comparing LTPP, short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and (short-term) solution-focused therapy in long-standing depressive and anxiety disorders, the authors assessed the effects of the short-term treatment groups at predefined time points that did not exactly represent end of therapy for the short-term treatments. Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49,Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Laaksonen, Raitasalo, Haaramo and Järvikoski54 Mean duration of treatment was 5.7 months and 7.5 months respectively for these treatments. Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49 To include the study by Knekt et al in this meta-analysis, we used the effects of the short-term treatments assessed after 9 months, which is the time point following most closely the end of the short-term treatments. As the effect sizes at 9 months were almost identical to those found at 7 months, no bias was introduced by this procedure. For LTPP we used the outcome assessed after 36 months (end of treatment). In another new RCT, Bateman & Fonagy compared LTPP (mentalisation-based treatment) with a structured clinical management approach in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. Reference Bateman and Fonagy45 In addition, we received further

Fig. 1 Selection of trials for update of authors’ 2008 meta-analysis of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP). Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16

information about another RCT of LTPP which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Reference Huber and Klug48 Huber & Klug provided us with data on the comparison groups of their study that were unavailable at the time of our previous meta-analysis. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16,Reference Huber and Klug48 Thus, we included this study in this meta-analysis as another RCT. As both the analytic psychotherapy and the long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy group of that study fulfilled our criterion for LTPP, we included both treatments in this category. The ten studies included are described in online Table DS1.

Tests for publication bias

To reduce the ‘file drawer’ effect we tried to identify unpublished studies through the internet and by contacting researchers. To test for publication bias we calculated correlations between sample size and between-group effect sizes across studies. A significant correlation may indicate a publication bias in which larger effect sizes in one direction are more likely to be published. Reference Begg, Cooper and Hedges55 Alternatively, the standard error instead of the sample size can be used to test for publication bias. Owing to the small number of studies providing follow-up data, we assessed these correlations only for the post-treatment between-group effect sizes. Since for comparisons with treatment as usual (TAU) smaller sample sizes (and larger between-group effect sizes) can be expected than for a comparison with a specific form of psychotherapy, we calculated partial correlations in order to control for the type of comparison condition (TAU v. specific psychotherapy). According to the results, the mean partial correlation between outcome and sample size was r p = 0.05 (range –0.06 to 0.14, P>0.73); for outcome and standard error, r p was 0.16 (P>0.46). As another test for publication bias we assessed the fail-safe number according to Rosenthal: this is the number of non-significant, unpublished or missing studies that would need to be added to a meta-analysis in order to change the results of the meta-analysis from significant to non-significant. Reference Rosenthal39 An effect size can be regarded as robust if the fail-safe number exceeds 5K + 10, where K is the number of studies. Reference Rosenthal56 For overall outcome the fail-safe number was 66. As this exceeds 60 (5K + 10), the effect can be regarded as robust. Summing up, we did not find any cogent indication of publication bias.

Total number of participants

The ten studies included encompassed 466 patients treated with LTPP and 505 patients receiving comparative treatments.

Therapy duration

For LTPP the mean number of sessions in the ten studies was 120.5 (s.d. = 117.5) and the mean duration of therapy was 78.0 weeks (s.d. = 38.2). For the treatments in the control groups the mean number of sessions was 45.4 (s.d. = 28.1) and the mean duration of therapy was 62.9 weeks (s.d. = 24.0).

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up assessments were carried out in three studies, at intervals of 1–8 years. Reference Huber and Klug48,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51,Reference Bateman and Fonagy57

Mental disorders

The ten controlled studies of complex mental disorders included the treatment of patients with long-standing depressive and anxiety disorders (two studies), Reference Huber and Klug48,Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49 cluster C personality disorders (one study), Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 borderline personality disorder (five studies), Reference Bateman and Fonagy11,Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13,Reference Bateman and Fonagy45,Reference Gregory, Chlebowski, Kang, Remen, Soderberg and Stepkovitch47,Reference Korner, Gerull, Meares and Stevenson50 and eating disorders (two studies). Reference Bachar, Latzer, Kreitler and Berry44,Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46 As the number of studies was too small to conduct separate analyses for specific disorders we combined them into one group called ‘complex mental disorders’.

Comparison groups

The psychotherapeutic treatments applied in the comparison groups included cognitive (behavioural) therapy (CBT/CT; three groups), Reference Bachar, Latzer, Kreitler and Berry44,Reference Huber and Klug48,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 cognitive analytic therapy (one group), Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46 dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT; one group), Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg13 short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (one group), Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49 solution-focused therapy (one group), Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49 family therapy (one group), Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46 structured clinical management (one group), Reference Bateman and Fonagy45 and routine psychiatric treatment as usual (four groups). Reference Bateman and Fonagy11,Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46,Reference Gregory, Chlebowski, Kang, Remen, Soderberg and Stepkovitch47,Reference Korner, Gerull, Meares and Stevenson50 In addition, one study of eating disorders included nutritional counselling as another control condition. Reference Bachar, Latzer, Kreitler and Berry44 The authors described this condition as not including psychotherapy. Including nutritional counselling as one of the control conditions of LTPP might lead to underestimating the effects of the control conditions. For this reason we did not include this therapy in the comparison conditions of this meta-analysis. Because of the small number of studies examining one specific comparison treatment, we did not carry out separate analyses for the different comparison conditions (e.g. LTPP v. CBT) but combined the treatments into one group called ‘less intensive forms of psychotherapy’. According to this procedure the question of whether LTPP yielded a better outcome than less intensive forms of psychotherapy was studied.

Treatment manuals

Treatment manuals or manual-like guidelines for LTPP were applied in all but two studies. Reference Huber and Klug48,Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49

Tests for heterogeneity

We used the Q statistic to test for heterogeneity of between-group effect sizes, Reference Hedges and Olkin33,Reference Rosenberg, Adams and Gurevitch35 and the I Reference Gabbard2 index to assess the degree of

Table 1 Comparison of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy with other forms of psychotherapy: between-group effect sizes

| Hedges' d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome domain | Number of comparisons | d a | 95% CIb | Q | I 2, % |

| Overall effectiveness | 10 | 0.54 (0.52) | 0.26–0.83 | 11.72 | 23 |

| Target problems | 9 | 0.49 (0.48) | 0.27–0.71 | 9.12 | 12 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 9 | 0.44 (0.41) | 0.15–0.73 | 11.52 | 31 |

| Personality functioning | 7 | 0.68 (0.63) | 0.31–1.04 | 5.97 | 0 |

| Social functioning | 8 | 0.62 (0.59) | 0.18–1.06 | 12.44 | 44 |

ITT, intention to treat.

a Adjusted for ITT sample.

b Unadjusted d.

heterogeneity (Table 1). Reference Huedo-Medina, Sanchez-Meca, Botella and Marin-Martinez36 For Q, all tests of significance yielded insignificant results (P≥0.09). The I Reference Gabbard2 index for overall outcome, target problems, symptoms, personality functioning and social functioning indicated low to moderate heterogeneity (Table 1). Reference Huedo-Medina, Sanchez-Meca, Botella and Marin-Martinez36 For follow-up, the number of studies providing data was too limited to calculate reasonable Q and I Reference Gabbard2 statistics.

Correlation of quality ratings with outcome

In order to examine the relationship between study quality and outcome the between-group effect sizes were correlated with the total score of the Jadad scale for overall outcome, target problems, general symptoms, personality functioning and social functioning. Owing to the small number of studies providing follow-up data, correlations were only calculated for post-treatment assessment effect sizes. For this purpose, the average quality score of the two raters was used. All correlations were non-significant (P>0.14, r s –0.13 to 0.53). Although not statistically significant, the Spearman correlation was relatively high for symptoms (r = 0.53). Accordingly, studies of higher quality tended to yield larger between-group effect sizes in favour of LTPP for psychiatric symptoms.

Effects of LTPP v. other methods of psychotherapy

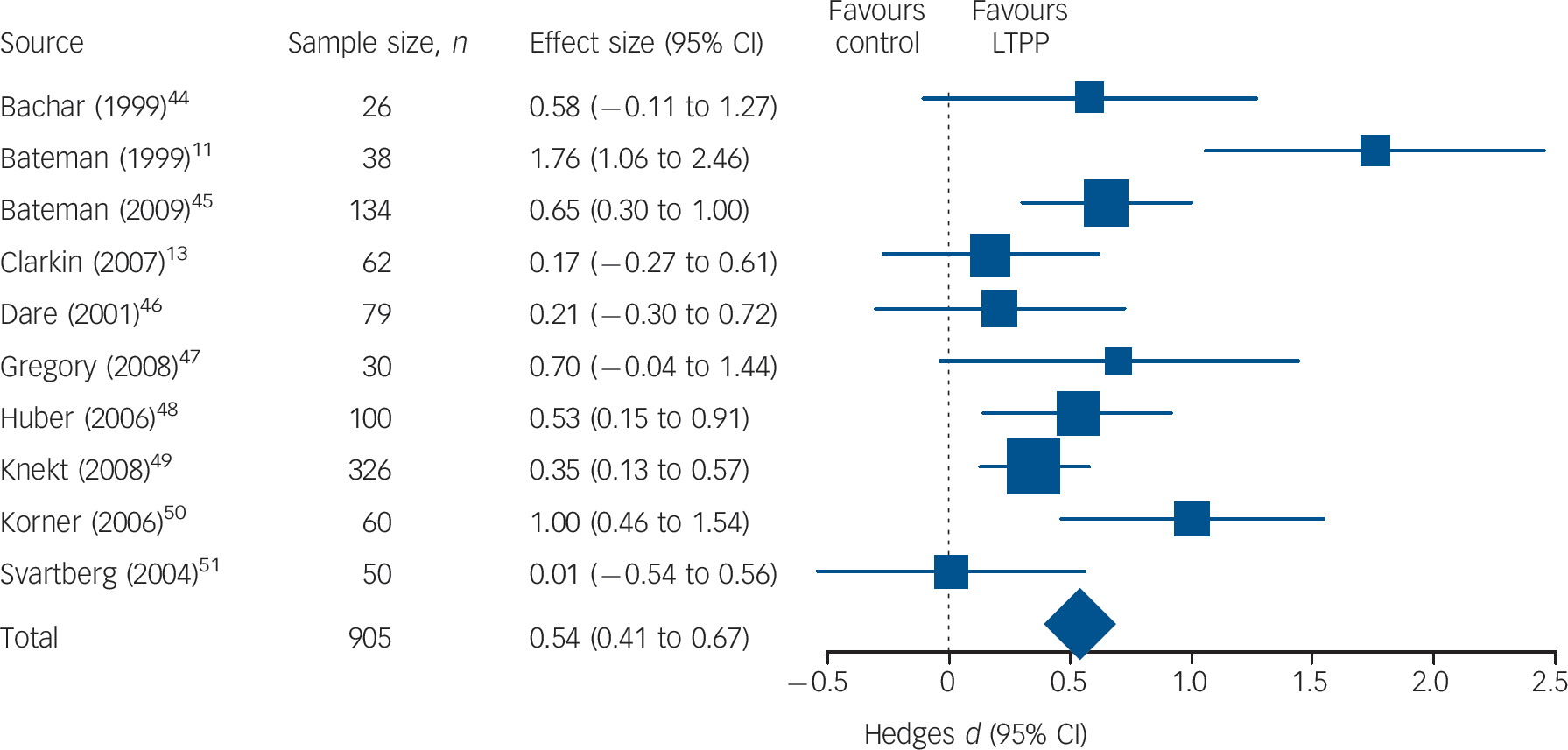

Because of the small number of studies providing data for follow-up assessments, between-group effect sizes were only assessed for the post-therapy data, except for some preliminary analyses. Between-group effect sizes (Hedge’s d) in overall outcome

Fig. 2 Comparative effects of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP) on overall outcome (number of patients in analysis sample may differ from intention-to-treat sample).

are presented for each of the ten studies (Fig. 2). The random effects model was applied in order to aggregate effect sizes across studies: the differences in outcome between LTPP and other forms of psychotherapy in complex mental disorders were 0.54, 0.49, 0.44, 0.68 and 0.62 respectively for overall outcome, target problems, psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning and social functioning (Table 1). The ITT analysis yielded similar results (Table 1). According to Cohen these effect sizes can be regarded as medium to large. Reference Cohen41 All between-group effect sizes differed significantly from zero (P<0.05). Effect sizes can be transformed into percentiles: Reference Cohen41 for example, a between-group effect size of 0.54 as identified in overall outcome indicates that after treatment with LTPP, patients on average were better off than 70% of the patients treated in the comparison groups. Only three studies provided data to assess between-group effect sizes for follow-up assessments. Reference Huber and Klug48,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51,Reference Bateman and Fonagy57 For this reason the results are only preliminary. For these three studies the between-group effect sizes were 0.55, 0.54, 0.48, 0.76 and 0.37 respectively for overall outcome, target problems, psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning and social functioning. According to these data the differences in favour of LTPP at follow-up are comparable with those at the end of treatment.

Correlations of outcome with dosage and duration

Including all treatment conditions (LTPP and non-LTPP), all outcome variables except for target problems showed significant Spearman correlations with the number of sessions (Table 2). Treatment duration was significantly correlated with improvements

Table 2 Spearman correlations of outcome (pre-post treatment effect sizes) with duration of therapy and number of treatment Sessions

| Overall outcome | Target problems | Psychiatric symptoms | Personality functioning | Social functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All treatment conditions | |||||

| Duration | 0.36* | 0.24 | 0.39* | 0.19 | 0.50* |

| Sessions | 0.54** | 0.33 | 0.37* | 0.48* | 0.63** |

| LTPP only | |||||

| Duration | 0.59* | 0.28 | 0.83** | 0.18 | 0.57* |

| Sessions | 0.68* | 0.28 | 0.67* | 0.31 | 0.79** |

| Control conditions only | |||||

| Duration | –0.10 | – 0.23 | –0.19 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Sessions | 0.02 | – 0.05 | –0.19 | _a | 0.20 |

LTPP, long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy.

a Insufficient data to calculate correlations.

* P<0.05

** P<0.01 (one-tailed).

in overall outcome, psychiatric symptoms and social functioning. The other correlations were of small to medium size but insignificant owing to the small number of conditions. Both the direction and significance of correlations of outcome with duration or dosage of therapy are consistent with the results that showed superiority of LTPP over shorter-term treatments.

In some studies treatment lasted for a year or more but comprised fewer than 50 sessions (online Table DS1). In order to control for the effect of dosage of LTPP, we additionally assessed Spearman correlations between pre–post effect sizes and the number of sessions for the LTPP conditions only (Table 2). Again, all correlations were positive. These correlations were large (>0.50) and significant for overall outcome, symptoms and social functioning. For target problems and personality functioning, small to medium correlations were found that were insignificant. Thus, the inclusion of studies in the LTPP group in which the number of sessions was less than 50 can be assumed to have reduced the effects of LTPP. In the control conditions only, no significant correlation was found (Table 2).

As a further check regarding the importance of dosage, we assessed between-group effect sizes without those studies in which fewer than 50 sessions were applied in the LTPP conditions (Dare et al, Bachar et al, Svartberg et al). Reference Bachar, Latzer, Kreitler and Berry44,Reference Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure and Dodge46,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 For all outcome measures the effect sizes increased after exclusion of the these three studies (overall outcome from 0.54 to 0.66; target problems from 0.49 to 0.55; psychiatric symptoms from 0.44 to 0.55; personality functioning from 0.68 to 0.77; social functioning from 0.62 to 0.72).

Discussion

A considerable proportion of patients with chronic mental disorders or personality disorders do not benefit sufficiently from short-term psychotherapy. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1,Reference Perry, Banon and Floriana3 Long-term psychotherapy, however, is associated with higher direct costs than short-term psychotherapy. For this reason it is important to know whether the effects of long-term psychotherapy exceed those of short-term treatments. In this meta-analysis, LTPP was superior to less intensive methods of psychotherapy in complex mental disorders. Furthermore, we found positive correlations between outcome and duration or dosage of therapy. Both of these results are consistent with data on dose–effect relations. Reference Kopta, Howard, Lowry and Beutler1

One limitation of this meta-analysis may be seen in the scarcity of controlled studies. Further studies of LTPP are required to confirm the results and allow for more refined analyses. With a small number of studies it is of particular importance to test for publication bias. For that purpose, we applied several measures. Fail-safe number analysis indicated that for overall outcome, 66 studies would need to be added to this meta-analysis in order to change the results of the meta-analysis from significant to non-significant. Furthermore, we found no significant correlation between outcome and sample size nor with standard error of effect sizes. We also found no significant correlation between outcome and the methodological quality of the studies as assessed using the scale proposed by Jadad et al. Reference Jadad, Moore, Carroll, Jenkinson, Reynolds and Gavaghan43 However, the size of some correlations may indicate a systematic relationship, in that studies of higher quality tended to yield larger between-group effect sizes in favour of LTPP. Another limitation can be seen in the small number of studies that reported follow-up assessments. It is of interest to know whether the between-group effect sizes in favour of LTPP are stable beyond the end of treatment. The results of our previous meta-analysis suggest that the effects of LTPP even increase after the end of treatment. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung16 When follow-up data from the studies included are available, this question can be addressed directly. As another limitation, not all studies reported ITT analyses. In this meta-analysis, however, we could show that adjusting for missing ITT data did not substantially change the results. Nonetheless, future studies should include ITT analyses whenever possible.

Duration of therapy

There is no generally accepted standard duration for LTPP. We included studies that lasted for at least a year or in which at least 50 sessions were applied. In some studies treatment lasted for a year or more but comprised fewer than 50 sessions; for this reason, some of these studies were included in previous meta-analyses as short-term. This was true, for example, for the study by Svartberg et al in which 40 sessions were applied. Reference Leichsenring, Rabung and Leibing27,Reference Svartberg, Stiles and Seltzer51 Apparently, the inclusion of studies depends on the question of research addressed and the specific definition that is used in a meta-analysis. The correlations between dosage and outcome in the LTPP studies reported above suggest that the inclusion of studies in which LTPP lasted for fewer than 50 sessions reduced the treatment effects of LTPP. However, including only studies that fulfilled both the dosage and the duration criteria would have further reduced the already small number of studies. Future meta-analyses of LTPP or of long-term psychotherapy in general should include studies that fulfil both the dosage and the duration criteria. Furthermore, a differentiation between long-term, medium-term and short-term therapy might be useful.

Critical discussion of results

This meta-analysis took several points of critique put forward against our 2008 meta-analysis into account, such as lack of between-group effect sizes or of ITT analyses, possible publication bias or inclusion of inactive control conditions. Reference Kriston, Hölzel and Härter17,Reference Beck and Bhar58 According to the results presented here we did not find cogent indication for any systematic bias. The methodological quality both of our meta-analyses and of the studies included is comparable to that of many studies of CBT. Reference Leichsenring and Rabung59

Some controlled studies did not meet the inclusion criteria because the majority of patients had not completed their treatment when the effect sizes were assessed. This was true, for example, for the studies by Brockmann et al, Doering et al, Giesen-Bloo et al and Puschner et al. Reference Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Spinhoven, van Tilburg, Dirksen and van Asselt15,Reference Brockmann, Schlüter and Eckert60–Reference Doering, Hörz, Rentrop, Fischer-Kern, Schuster and Benecke62 In the study by Giesen-Bloo, for example, 19 of 42 patients treated with LTPP (45%) were still in treatment when outcome was assessed, and only 2 patients had completed LTPP; in the comparison group 27 of 44 patients (61%) were still in treatment, and only 6 patients had completed the treatment. Reference Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Spinhoven, van Tilburg, Dirksen and van Asselt15 Data from ongoing treatments do not provide reliable estimates for treatment outcome at termination or follow-up, for example if patients had received only half of the ‘dose’ of treatment when outcome was assessed. By analogy, if one runner enters a 100 m race and a second enters a 10 000 m race, the time taken after 100 m will not be representative of the short-distance speed of the second runner. The runners will adapt their speed to the short or long distance they are going to face. This is true for patients in psychotherapy as well. Reference Knekt, Lindfors, Harkanen, Valikoski, Virtala and Laaksonen49 Psychotherapy is not a drug that works equally under different conditions, but a psychosocial process.

We compared the effects of LTPP with a group of mixed psychotherapeutic treatments. The control conditions consisted of specific forms of psychotherapy, including established forms such as CBT or DBT, as well as several TAU conditions. Including TAU can be assumed to reduce the mean effect size of the control group; on the other hand, the control conditions included not only short-term psychotherapy but also long-term psychotherapy applied as long as LTPP in the respective studies (e.g. DBT, CBT), in turn increasing the mean effect of the control condition. It is noteworthy that it was on average that duration and the number of treatment sessions applied was higher in the LTPP conditions. Thus, we used the alternative treatments as an unspecific (mixed) control group including both TAU and specific forms of alternative psychotherapy. Consequently, we do not claim that LTPP is superior to any specific form of psychotherapy in complex mental disorders that is carried out equally intensively, rather that it is superior to less intensive forms of psychotherapeutic interventions in general. We expect this to be true for other more intensive approaches of formal psychotherapy as well, for example that higher-dose CBT is superior to lower-dose CBT in borderline personality disorder. For psychodynamic psychotherapy this should also be true. With regard to the hierarchy of evidence, our comparison of LTPP with a mixed control group including TAU and specific psychotherapy is stricter than a comparison with a waiting-list group, placebo therapy or pure TAU, but less strict (and specific) than a comparison with specific or established forms of psychotherapy only. Reference Chambles and Hollon63,Reference Gabbard, Gunderson and Fonagy64

Future research

Without doubt comparisons of LTPP with specific therapies are desirable, both short-term and long-term. At present, however, not enough studies are available. For CBT or DBT more comparative studies exist. Thus, it would be interesting to compare long-term CBT or DBT with short-term CBT or DBT in specific mental disorders. For some mental disorders for which response rates are not satisfactory, such as social anxiety disorder, experts in the field propose increasing treatment duration. Reference Zaider and Heimberg65

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Martin Rock (Yeshiva University, New York, USA) for information concerning the study by Clarkin et al, and Drs D. Huber and G. Klug and Drs A. Bateman and P. Fonagy for giving us access to their data. We also thank John Clarkin, PhD (Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, USA), Ivan Eisler, PhD (Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, UK), Paul Knekt, PhD (National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland) and Martin Svartberg, MD, PhD (Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) for information about their studies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.