Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a highly debilitating psychiatric disorder characterised by persistent thoughts, urges and repetitive behaviours. The lifetime prevalence of OCD is estimated to be between 1 and 3%,Reference Ruscio, Stein, Chiu and Kessler1 and it is thought to be among the most impairing non-fatal illnesses in the world.Reference Ayuso-Mateos2 Current neurobiological models of OCD emphasise the role of cortico–striatal–thalamic circuitry in this disorder.Reference Kariuki-Nyuthe, Gomez-Mancilla and Stein3, Reference Wu, Hanna, Rosenberg and Arnold4 Twin and family studies have established a strong genetic effect in susceptibility to childhood-onset OCD (45–65% heritable) and in adult-onset OCD (27–47% heritable).Reference van Grootheest, Cath, Beekman and Boomsma5–Reference Bolton, Rijsdijk, Eley, O'Connor, Briskman and Perrin8

Twin studies have also indicated specific genetic contributions to brain changes in OCD, although the relevant contributing genes have not been identified.Reference den Braber, van ’t Ent, Boomsma, Cath, Veltman and Thompson9–Reference den Braber, van ’t Ent, Cath, Wagner, Boomsma and de Geus11 Work such as that undertaken by the Enhancing Neuro Imaging through Meta Analysis (ENIGMA) Consortium has, however, provided methods to identify specific genetic contributors to brain alterations. For example, a recent large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) of measures derived from structural brain magnetic resonance imaging scans of 30 717 individuals from 50 cohorts identified genetic variants associated with the putamen and caudate nucleus volumes.Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12

Few studies have integrated neurogenetic and brain imaging methods to study OCD. Prior studies mostly examined candidate genes rather than using a genome-wide approach.Reference Wu, Hanna, Easter, Kennedy, Rosenberg and Arnold13 Here we present the first genome-wide investigation of the overlap between the genetic risk for OCD and genetic influences on the volumes of subcortical brain structures. We combined data from the International OCD Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC) GWASReference Stewart, Yu, Scharf, Neale, Fagerness and Mathews14 and the ENIGMA GWAS of brain structureReference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12 to assess: (a) whether the same single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) influences both OCD and subcortical brain volume phenotypes (pleiotropy), (b) whether the same SNP has the same direction of effect on OCD risk as its effect on subcortical brain volume (concordance), and (c) whether genetic variants associated with specific subcortical brain volumes are significantly associated with OCD risk.

Method

Description of original association studies

We obtained summary statistics from the IOCDF-GC GWAS of OCD,Reference Stewart, Yu, Scharf, Neale, Fagerness and Mathews14 which comprised three case-control populations (totalling 1465 cases of OCD and 5557 controls) combined with 299 complete trios (which includes both parents and their OCD-diagnosed child, henceforth referred to as the proband). After removing the ancestral outliers (101 non-European trios were removed), all remaining participants were of European ancestry. GWAS summary statistics were genome controlled to account for residual inflation factors (see Methods in Stewart et al., 2013Reference Stewart, Yu, Scharf, Neale, Fagerness and Mathews14 for complete details). Additionally, we used GWAS summary statistics from a recent, large-scale meta-analysis by the ENIGMA Consortium of subcortical brain volumes across 50 cohorts worldwide.Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12 These cohorts consist of healthy controls as well as participants diagnosed with neuropsychiatric disorders (including anxiety, Alzheimer's disease, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, epilepsy and schizophrenia). These data further comprised separate GWASs of seven subcortical brain volumes (nucleus accumbens, amygdala, caudate nucleus, hippocampus, globus pallidus, putamen and thalamus) and total intracranial volume (ICV) in 13 171 participants from the GWAS discovery sample. Brain volume data were extracted following a harmonised protocol that uses validated, robust segmentation algorithmsReference Fischl, Salat, Busa, Albert, Dieterich and Haselgrove15 to ensure maximum cross-site comparability. All participants were of European ancestry as verified by multidimensional scaling analysis and GWAS test statistics were genome controlled to adjust for spurious inflation factors. Prior to these analyses we verified that there were no participants diagnosed with OCD included in the brain volume GWASs from the ENIGMA Consortium (see Methods in Hibar et al., 2015Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12 and Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.62). All studies were approved by a local ethics board prior to the recruitment of participants and all participants gave written, informed consent before participating.

Post-processing of genetic data

After applying quality control and filtering rules to the imputed OCD GWAS data, 7 658 445 SNPs remained (see supplementary materials in Stewart et al., 2013Reference Stewart, Yu, Scharf, Neale, Fagerness and Mathews14 for imputation, the statistical inference of SNPs that were not directly genotyped and quality control details). Similarly, 8 398 366 SNPs were consistently available for all eight brain structures after applying quality control and filtering rules to the imputed brain volume GWAS data (see Methods in Hibar et al., 2015Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12 for imputation and quality control details). To statistically compare the OCD and eight brain volume GWASs, we used the 6 946 379 overlapping SNPs that passed quality control and filtering rules in all data sets.

With these data, we performed a clumping procedure in PLINKReference Purcell, Neale, Todd-Brown, Thomas, Ferreira and Bender16 to identify an independent SNP from every linkage disequilibrium (LD) block across the genome. The clumping procedure was performed separately for each of the eight brain volume GWASs using an 800 kb window, with SNPs in LD (r 2 > 0.25), in the European reference samples from the 1000 Genomes Project (Phase 1, version 3) (http://www.internationalgenome.org/). The SNP with the lowest P-value within each LD block was selected as the index SNP representing that LD block, and all other SNPs in the LD block were dropped from the analysis. After applying the clumping procedure, there were eight independent sets of SNPs representing the total variation explained across the genome, conditioned on the significance in each brain volume GWAS. For each of these eight sets of SNPs, we then determined the corresponding OCD GWAS test statistic for each independent index SNP and used these data sets for subsequent analyses.

Tests of pleiotropy and concordance

We used SNP effect concordance analysis (SECA)Reference Nyholt17 to determine the extent of genetic overlap between OCD and each brain volume. Within SECA we performed a global test of pleiotropy using a binomial test at 12 P-value levels: P ≤ (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1). For each paired brain volume and OCD set, we separately ordered SNPs based on their P-value for association with each trait. We iterated through each of the 12 P-value levels and determined the total number of overlapping SNPs between the two traits at each P-value threshold and compared that number to the expected random overlap under the null hypothesis of no pleiotropy, using a binomial test. We stepped through each of the 12 P-value levels to compare all levels in the brain volume GWAS to all levels of the OCD GWAS (144 comparisons in total). We tallied the number of comparisons with evidence of overlap at a nominally significant level of P ≤ 0.05. To evaluate the global level of pleiotropy, we generated 10 000 permuted data sets – containing all the possible combinations for a given brain volume v. OCD comparison – and determined if the number of significance thresholds with genetic overlap was significantly greater than chance.

Similarly, we estimated concordance using SECA. We determined whether or not there was a significant (P ≤ 0.05) positive or negative trend in the effect of the overlapping SNPs at each of the 12 P-value thresholds using a two-sided Fisher's exact test. The direction of effect for each SNP was determined by the sign of the beta (β) of the SNP regression coefficient from each meta-analysis. In the OCD GWAS, a positive β value for a SNP was associated with an increased risk of developing OCD (a negative β value indicates a protective variant). A positive β value for a SNP in a brain volume GWAS indicates that that SNP is associated with an increase in brain volume (a negative β value indicates a SNP is associated with a reduction in brain volume). We estimated the global level of concordance between a given brain volume phenotype and OCD by generating 10 000 permuted data sets, repeating the Fisher's exact test procedure, and determined if the number of significant overlapping thresholds was significantly greater than would be expected by chance (see Nyholt et al., 2014Reference Nyholt17 for details of the SECA analysis).

We tested for pleiotropy and concordance between OCD and all eight brain structures. Given the number of tests performed, we set a Bonferroni-corrected significance level at P* = 0.05/(2 * 8) = 3.13 × 10−3.

Conditional false discovery rate to detect OCD risk variants

We also examined if conditioning the OCD GWAS results on genetic variants that influence brain volume could improve our ability to detect variants associated with OCD.Reference Andreassen, Thompson, Schork, Ripke, Mattingsdal and Kelsoe18 For a given brain-volume phenotype, we selected subsets of SNPs at 14 false discovery rate (FDR) thresholds with q-values ≤ (1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1) and looked up the corresponding P-values for each SNP subset in the OCD GWAS. We then applied the FDR methodReference Benjamini and Hochberg19 to each subset of P-values in the OCD GWAS. Individual SNPs were considered significant if the P-value was lower than the significance threshold allowing for an FDR of 5%, conditioned on any subset of SNPs from the brain volume GWASs. The LD-pruned data are still required for the conditional FDR SNP analysis because regions with varying amounts of SNPs within an LD block can affect the ranking and re-ranking of SNPs under the conditional models. However, the chosen SNP included in the model is likely just a ‘proxy’ for SNPs in the LD block and should not necessarily be considered a causal variant or even the most significant SNP in terms of its overlap between traits.

Estimating genetic correlation using LD score regression

To replicate significant findings from our primary analysis performed with SECA we used an alternative method, LD score regression, which estimates a genetic correlation between two trait pairs based on the GWAS summary statistics of each trait analysed separately.Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Loh, Finucane, Ripke and Yang20 LD score regression estimates a genetic correlation with a fitted linear model of Z-scores obtained from the product of the significance statistics for each SNP in a given set of GWAS results compared to the level of LD at a given SNP. SNPs in high LD are expected to have high Z-scores in polygenic traits with common genetic overlap.Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day and Loh21 The genetic correlation from LD score regression is analogous to the concordance test in SECA, which incorporates the sign of the regression coefficients for each SNP tested to determine the direction (positive or negative) of the relation between traits.

SECA models on a healthy-only subset of the ENIGMA GWAS data

We used the site-level GWAS summary statistics available from the ENIGMA Consortium to exclude any participating sites with any patients with a diagnosis of a neuropsychiatric illness. In this way we were able to obtain a data set of GWAS summary statistics across sites comprising healthy control participants for comparison with the OCD GWAS. In total, the ‘healthy-only’ data set consisted of 9318 participants from 16 sites.

Results

Evidence for pleiotropy between brain volume and OCD risk variants

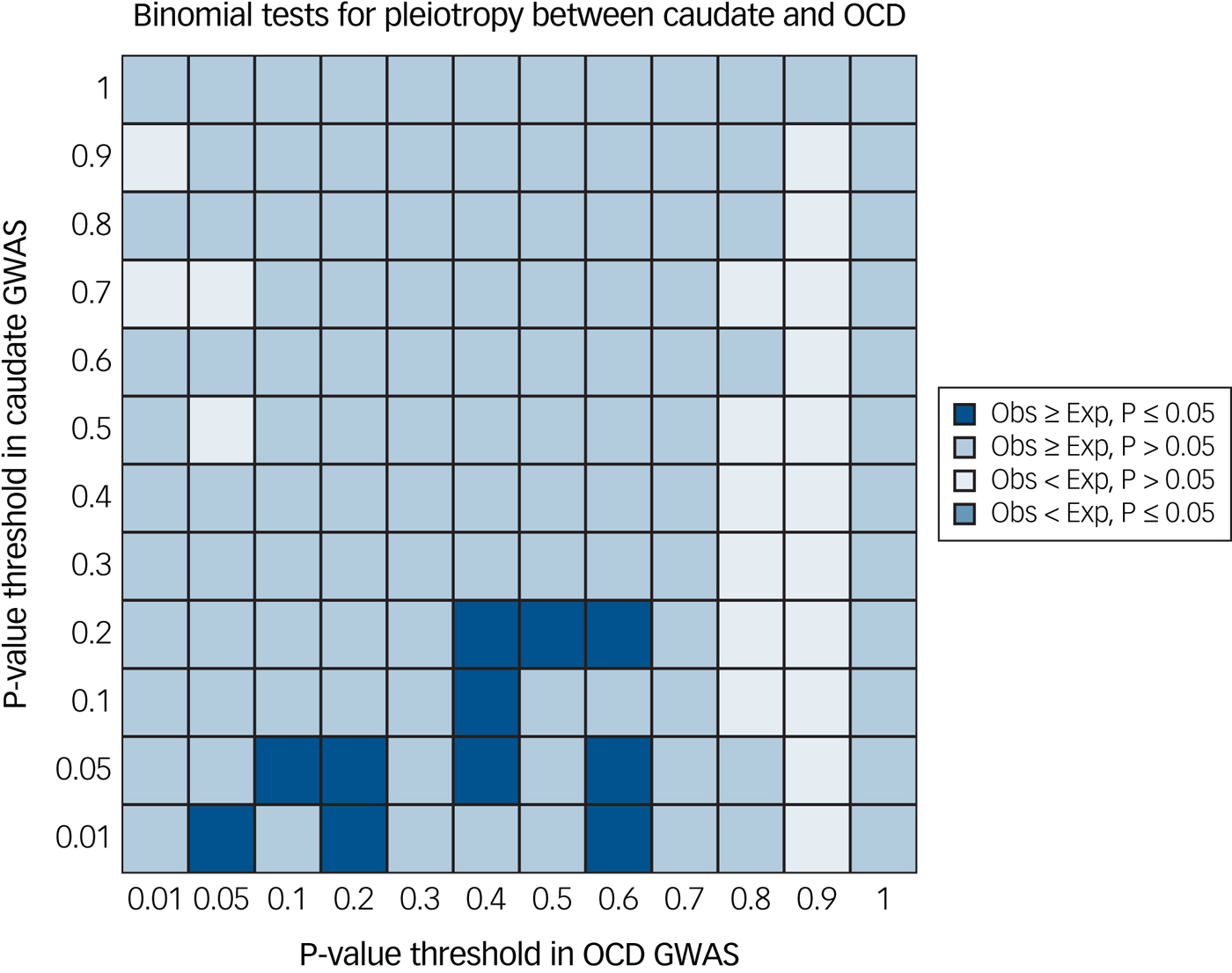

We did not find significant evidence of global pleiotropy (same SNP, regardless of direction of effect) in any of the brain structures investigated after correction for multiple comparisons. Of the eight regions, evidence of pleiotropy was greatest between variants affecting the caudate volume and OCD risk (P = 0.004; Fig. 1), but this was not significant after correction for multiple testing. The statistical evidence of pleiotropy for the six other subcortical structures and total ICV was less strong: putamen (P = 0.013), nucleus accumbens (P = 0.09), hippocampus (P = 0.06), thalamus (P = 0.09), ICV (P = 0.29), amygdala (P = 0.30) and globus pallidus (P > 0.99). Plotted output from the global pleiotropy test for each comparison is available in Supplementary Fig. 1(a–h).

Fig. 1 Global evidence of pleiotropy between caudate nucleus volume and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) genome-wide association study (GWAS). We found trend-level evidence (P = 0.004) of pleiotropy between gene variants affecting both caudate nucleus volume and OCD risk using single nucleotide polymorphism effect concordance analysis.Reference Nyholt17 Exp, expected; Obs, observed.

Concordance between basal ganglia structures and OCD

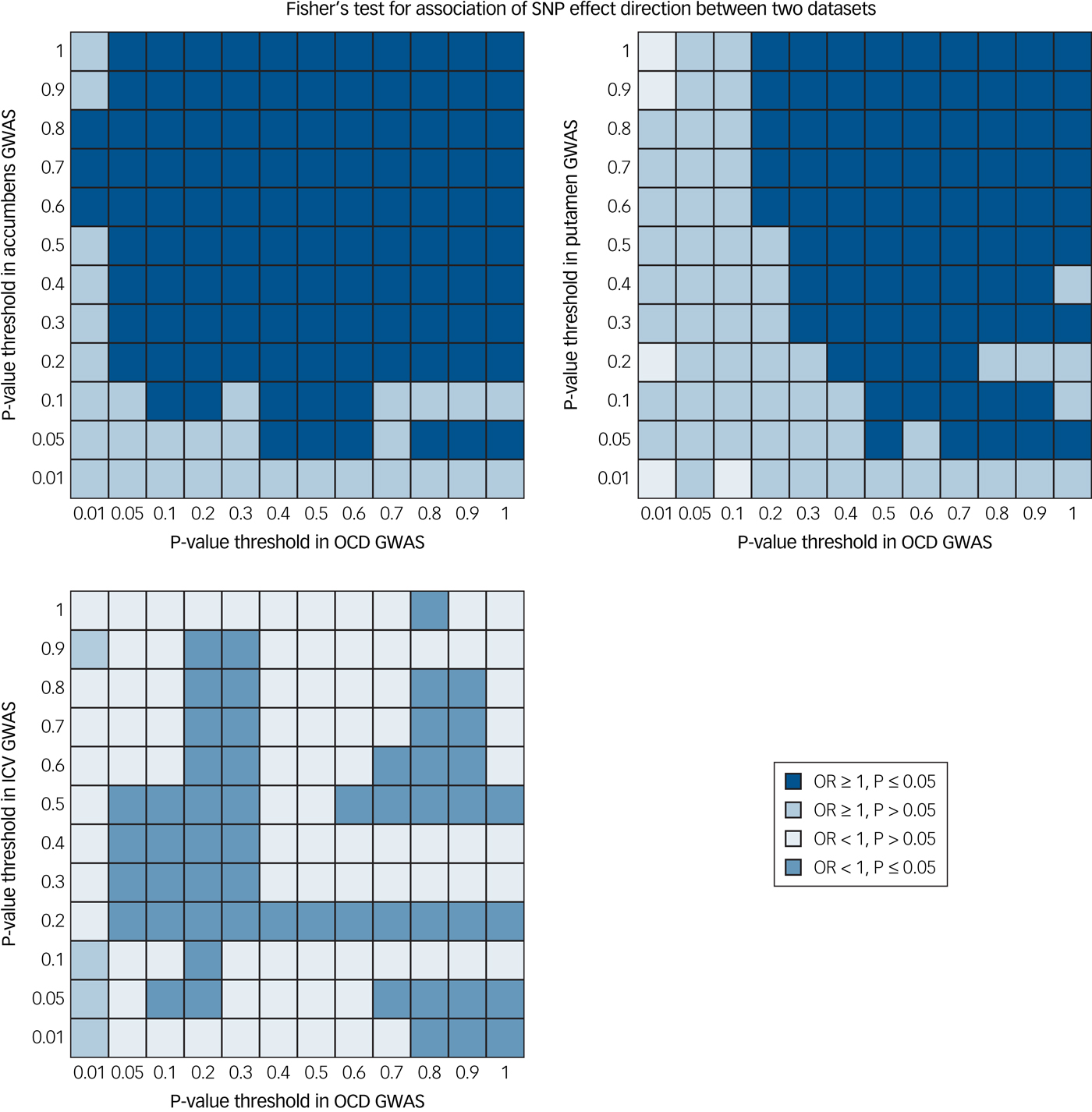

We found significant evidence of positive concordance (same SNP, same direction of effect) between OCD risk variants and variants that increase the volume of both the nucleus accumbens (P = 2.0 × 10−4) and the putamen (P = 8.0 × 10−4) (Fig. 2). Further, we found trending significant evidence of negative concordance between OCD risk variants and variants that decrease ICV (P = 0.01). The remaining five subcortical structures did not show evidence of concordance at the study-wide significance level: globus pallidus (P = 0.05), caudate nucleus (P = 0.08), thalamus (P = 0.22), hippocampus (P > 0.99) and amygdala (P > 0.99). Plotted output from the global concordance test for each comparison is available in Supplementary Fig. 2(a–h).

Fig. 2 Global evidence for concordant effects between brain volume and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) genome-wide association study (GWAS). We found positive concordance between gene variants affecting both accumbens volume and OCD risk (P = 2.0 × 10−4) and putamen volume and OCD risk (P = 8.0 × 10−4). Further, we found trend-level evidence of a negative concordance between gene variants affecting intracranial volume (ICV) and OCD risk (P = 0.01). Concordance tests were performed using single nucleotide polymorphism effect concordance analysis.Reference Nyholt17 OR, odds ratio.

Genetic variants influencing putamen, amygdala and thalamus volume provide improved ability to detect OCD risk variants

We performed a conditional FDR analysis by separately conditioning the OCD GWAS on each of the eight brain volume GWASs. When conditioning the OCD analysis on variants that influence putamen volume, one variant (rs149154047; q = 0.0375) was significantly associated with risk for OCD. Conditioning the OCD GWAS on variants affecting amygdala volume showed that one variant (rs534371; q = 0.0063) was significantly associated with risk of developing OCD. Finally, when conditioning the OCD GWAS on variants affecting thalamus volume, two variants (rs11872098, q = 0.0069 and rs116331752, q = 0.037) were significantly associated with risk of developing OCD. Results are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1 Significant variants associated with obsessive–compulsive disorder risk when conditioning on brain volume genome-wide association studies

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; BP, base pair; EA, effect allele; NEA, non-effect allele; Freq, allele frequency; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

a. The chromosome and base pair are given in h19b37 coordinates.

b. The allele frequency corresponds to the effect allele.

c. Tagging SNP corresponds to the most significant variant in a given linkage disequilibrium block (if different from the SNP chosen based on clumping in the brain volume genome-wide association study).

d. The effect in brain and effect in obsessive–compulsive disorder are both given in terms of the effect allele.

Replication of putamen and OCD genetic overlap using LD score regression

We successfully replicated the significant positive concordance between putamen and OCD GWAS using the LD score regression method (r g = 0.188; P = 0.02). We found only trending significant evidence of positive concordance between nucleus accumbens and OCD GWAS (r g = 0.218; P = 0.09). Marginal and trending significance for other brain regions and OCD risk detected with SECA were not replicated with this method. The full list of results, including pairwise comparisons over all traits, is tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2 Results of the comparison between each brain volume GWAS from ENIGMA with the OCD GWAS from the IOCDF using LD score regressionReference Bulik-Sullivan, Loh, Finucane, Ripke and Yang20

GWAS, genome-wide association study; ENIGMA, Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta Analysis; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; IOCDF, International OCD Foundation; LD, linkage disequilibrium; ICV, intracranial volume.

Relating putamen volume to OCD risk

When analysing a subset of the ENIGMA GWAS brain volume data comprising only healthy controls, we found significant positive genetic concordance between OCD risk and the volume of the putamen (P = 0.03) and the accumbens (P = 0.003).

Discussion

Our study has two key findings: First, there was a significant positive concordance between OCD risk variants and variants that increase the volume of the nucleus accumbens and the putamen, and these trends were replicated in the smaller healthy-only GWAS data set. Further supporting evidence using an alternate method estimated a significant genetic correlation between putamen volume and OCD risk and trend-level evidence of a positive genetic correlation between common genetic variants influencing nucleus accumbens volume and OCD risk. The genetic correlation between putamen volume and OCD risk is relatively high and is among the highest genetic correlations in comparison to a recent survey of traits.Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day and Loh21 Second, one variant influencing putamen volume (rs149154047), one variant influencing amygdala volume (rs544371) and two variants influencing thalamus volume (rs11872098 and rs116331752) were significantly associated with risk for OCD when respectively conditioned on the variants associated with the volume of these regions.

These data are somewhat consistent with current neurocircuitry and neuroimaging models of OCD that implicate fronto–striatal and fronto–limbic circuitries.Reference Shaw, Sharp, Sudre, Wharton, Greenstein and Raznahan22, Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon23 An anatomic likelihood estimation meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies including 343 people with OCD and 318 healthy controls found that grey-matter volume was smaller in fronto–parietal cortical regions, and greater in the putamen and the anterior prefrontal cortex in people with OCD.Reference Blokland, de Zubicaray, McMahon and Wright24 In another meta-analysis, studies including individuals with more severe OCD were significantly more likely to report greater basal ganglia volumes.Reference Radua and Mataix-Cols25 Another meta-analysis showed that people with OCD had reduced bilateral volumes of the left anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex, and larger bilateral thalamic volumes.Reference Rotge, Guehl, Dilharreguy, Tignol, Bioulac and Allard26 The recent multi-centre mega-analysis study from the OCD Brain Imaging Consortium showed, apart from smaller fronto–insular cortices, smaller volumes of the thalamus in people with OCD; differences in putamen volume between people with OCD and controls were most pronounced at an older age, perhaps suggesting altered brain ageing due to chronic compulsivity.Reference de Wit, Alonso, Schweren, Mataix-Cols, Lochner and Menchon23 The nucleus accumbens emerged as relevant to OCD in a number of recent imaging studies, and is a target for deep-brain stimulation for OCD.Reference Denys, Mantione, Figee, van den Munckhof, Koerselman and Westenberg27

The particular genetic variants that are jointly associated with specific subcortical brain structures and with the risk for developing OCD deserve further investigation. The SNP rs11872098, which is associated with thalamus volume, is located within an intron of the discs large-associated protein 1 (DLGAP1) gene (also known as SAPAP1). The IOCDF-GC, a multi-national consortium that performed the first GWAS of OCD, showed that several SNPs within DLGAP1 (rs11081062 was the most significant; P-value = 2.49 × 10−6) had trending significant associations with OCD.Reference Stewart, Yu, Scharf, Neale, Fagerness and Mathews14 DLGAP1, a postsynaptic density protein, interacts with discs large homolog 4 (DLG4) synaptic ion channel proteins to regulate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 605445).Reference Kim, Naisbitt, Hsueh, Rao, Rothschild and Craig28 In OCD, glutamate signalling may be disrupted in the cortico–striatal–thalamo–cortical circuits.Reference Kariuki-Nyuthe, Gomez-Mancilla and Stein3, Reference Wu, Hanna, Rosenberg and Arnold4 Further, the mouse ortholog of the closely related DLGAP3 gene, SAPAP3, causes compulsive-like behaviour when deleted in mice,Reference Wan, Ade, Caffall, Ilcim Ozlu, Eroglu and Feng29 and this behaviour can be optogenetically reversed by stimulating the lateral orbitofrontal cortex and its terminals in the striatum.Reference Burguiere, Monteiro, Feng and Graybiel30

The variant rs149154047, which is jointly associated with putamen volume and OCD risk, is 14 bp 5′ to the transcriptional start site of the R-spondin family, member 4 (RSPO4) gene and is an activator of the Wnt signalling pathway.Reference Blaydon, Ishii, O'Toole, Unsworth, Teh and Ruschendorf31 The Wnt signalling pathway is of particular interest due to its function in neurodevelopment. Dysregulation of this pathway has been postulated in contemporary models to be involved in the pathophysiology of a number of psychiatric disorders.Reference Okerlund and Cheyette32 Mutations in RSPO4 have thus far only been associated with the congenital, nonsyndromic, rare, autosomal recessive disorder, anonychia congenita (OMIM: 206800), which results in the absence of fingernails and/or toenails.Reference Wasif and Ahmad33

The variant rs534371, jointly associated with amygdala volume and OCD risk, is located within an intergenic region 137 kb 5′ to the transcriptional start site of lysozyme-like protein 1 (LYZL1). The LYZL family are thought to encode bacteriolytic lysozymes involved in host defense.Reference Jolles and Jolles34 The second variant that influences thalamus volume, rs116331752, is within an intron of the cytokine-dependent hematopoietic cell linker (CLNK) gene. CLNK is involved in the regulation of immunoreceptor signalling, specifically B cell-mediated antigen receptor signaling.Reference Cao, Davidson, Yu, Latour and Veillette35 Variation in CLNK is likely not related to normal immune function.Reference Utting, Sedgmen, Watts, Shi, Rottapel and Iulianella36 There are cases of OCD with acute onset after infection, referred to as pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (also known as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections).Reference Swedo, Leonard, Garvey, Mittleman, Allen and Perlmutter37 This form of OCD has been hypothesised to be secondary to both the neuroimmune reactions to the infectious trigger (often group A streptococcus) and to an inherent, genetically based, broader immune risk such as an overactive innate immune system.

A connection between CLNK, LYZL1 and RSPO4 with OCD risk and brain structure has not previously been established and these specific gene variants showed no evidence of cis-acting gene expression changes in brain tissue.Reference Ramasamy, Trabzuni, Guelfi, Varghese, Smith and Walker38 Interestingly, these SNPs were found in the amygdala and thalamus, which did not show significant evidence of pleiotropy or concordance in the SECA analyses. As the tests of concordance and pleiotropy are global tests of overlap, it is possible that a few variants can have a strong pleiotropic or concordant effect, but the global tests of significance do not detect it. Conditional FDR SNP analysis can provide additional information by identifying specific SNPs that would have otherwise gone unnoticed in the global tests of enrichment. However, more evidence is needed to verify the role of these variants in OCD risk.

Although we provide evidence for genetic overlap between subcortical brain volumes and OCD risk, our study has limitations. First, in theory the analysis could be biased if overlapping participants were present in both the ENIGMA and IOCDF-GC consortia. We contacted all principal investigators to verify that cohort members did not participate in both analyses. Still, it remains possible, but unlikely, that overlap exists. Second, the ENIGMA GWASs of brain volumes contain cohorts with healthy controls as well as people diagnosed with neuropsychiatric disorders, which may bias the interpretation of our findings and how they relate to OCD. However, a direct comparison of the GWAS summary statistics between the full ENIGMA results (including patients) and a subset of ENIGMA results (excluding patients) showed that they were very highly correlated (Pearson's r > 0.99) for all brain traits.Reference Hibar, Stein, Renteria, Arias-Vasquez, Desriviéres and Jahanshad12 This suggests that the pattern of effects in the brain volume GWAS is not likely driven by disease status. Third, environmental factors and stressors may explain a substantial portion of OCD risk, especially in the case of adult-onset OCD which is less heritable than adolescent-onset OCD. Environmental factors may also obscure genetic relationships and thus affect the ability to discover the pathways that influence both brain volume and risk of OCD. However, this endeavour to find the genetic overlap between brain volume and OCD risk using the largest data sets to date is worthwhile as it offers insights into the biology underlying this disorder. Fourth, we are comparing GWAS results performed on two different versions of the 1000 Genomes reference panel which could lead to spurious results for alleles that were poorly aligned or not present in later versions. However, the versions used are highly similar, with most changes focused on rare structural genomic variants that were not included in this study by design. Fifth, we provide evidence for four variants with joint effects on brain volume and OCD risk. However, these tests were conducted as an exploratory conditional analysis across several different FDR thresholds. These tests must be considered post hoc, but still suggest possible SNPs that may link brain volume changes and OCD risk. The conditional FDR analysis should be interpreted with care, and further investigation into these gene variants is needed to verify their status as putative risk variants. Investigations of DLGAP1 are already underway: a pilot study of 20 medication-naive paediatric patients with OCD investigated common variants in genes in the glutamate signalling pathway (including DLGAP1) and failed to find an association between variants in DLGAP1 and putamen volume.Reference Wu, Hanna, Easter, Kennedy, Rosenberg and Arnold13 Other gene candidates in the glutamatergic system have been studied in more detail,Reference Stewart, Mayerfeld, Arnold, Crane, O'Dushlaine and Fagerness39 including solute carrier family 1 member 1 (SLC1A1) which encodes a glutamate transporter in the postsynaptic density. However, the link between variants in SLC1A1 and OCD have had mixed results.Reference Wu, Hanna, Easter, Kennedy, Rosenberg and Arnold13, Reference Arnold, Macmaster, Hanna, Richter, Sicard and Burroughs40 Clearly, larger studies (including twin and family-based studies) would be better powered to assess the variants detected in our analysis. The newly formed ENIGMA-OCD working group is now examining both genome-wide genotyping and neuroimaging data from healthy controls and patients with OCD to further study these genetic relationships.

In conclusion, this is the first genome-wide study of the joint effect of genetic variation on both subcortical brain structures and risk for OCD, yielding results consistent with existing neurocircuitry models of OCD. Our findings emphasise the role of the glutamatergic system and a number of previously unstudied gene variants in this disorder. Based on our conditional FDR analysis, large imaging genomic studies (in the absence of a psychiatric phenotype) may be useful priors for constraining the genomic search space for finding associations with clinical outcomes.

Funding

ENIGMA was supported in part by a consortium grant (U54 EB020403 to P.M.T.) from the Institutes of the National Institutes of Health contributing to the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Initiative, including the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and National Cancer Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.62.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.