Introduction

Fines and fees are increasingly recognized as a form of racialized revenue extraction connected to marginalized communities’ alienation from government (McCoy Reference McCoy2015; Sanders and Conarck Reference Sanders and Conarck2017; Shaer Reference Shaer2019). After Michael Brown was killed by the Ferguson Police Department in 2014, a US Department of Justice investigation into the city’s police and courts demonstrated that the municipality was engaged in a practice that advocates now refer to as “policing for profit.” The city’s reliance on fines and fees to fund government functions grew from 13% to 23% of the total budget between fiscal years 2012 and 2015. From 2012 to 2014, the Department of Justice found that 85% of vehicle stops, 90% of citations, and 93% of arrests targeted Black people. In contrast, just two-thirds of Ferguson’s residents are Black (United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division 2015).

It wasn’t just a Ferguson problem, or even a Missouri problem. American cities’ reliance on fines and fees revenue increased significantly following the 2008 recession—as local tax revenues dropped and tax increases became less politically viable, jurisdictions increased the amounts of fines and fees and imposed them more frequently in order to fund government services (Harris, Ash, and Fagan Reference Harris, Ash and Fagan2020; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Huebner, Martin, Pattillo, Pettit, Shannon, Sykes, Uggen and Fernandes2017; Singla, Kirschner, and Stone Reference Singla, Kirschner and Stone2020).

Given that American jurisdictions are increasing their reliance on fines and fees revenue—and that police are the government officials charged with generating revenue—it stands to reason that more low-level police contact has occurred, and often with blatantly extractive intent. Although scholars have examined the collateral consequences of this increased reliance on fines and fees (Pacewicz and Robinson Reference Pacewicz and Robinson2020; Sances and You Reference Sances and You2017), comparatively few have explored the moment during which such revenue-raising actually occurs—namely, in the individual interactions between residents and the police via the issuance of a ticket. This “moment” of low-level contact has also been relatively understudied by scholars investigating the participatory consequences of contact with the criminal legal system. Work exploring how criminalization directly and indirectly influences political participation has exploded in recent years. Scholars have found that criminal legal contact (i.e., arrest, conviction, incarceration) consistently discourages voting (Burch Reference Burch2011; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010; White Reference White2019b). Such work has largely focused on the effects of highly disruptive contact with the criminal legal system such as incarceration and felony convictions (Burch Reference Burch2014; Lee, Porter, and Comfort Reference Lee, Porter and Comfort2014). Although ticketing involves potentially negative interactions with the state, it does not necessarily carry the disruptive consequences of a felony conviction and might thus politicize Americans in unique ways. This paper theorizes how local police practices affect voting behavior among stopped individuals and provides precisely estimated evidence of a causal effect.

Our project represents the first use of individual-level administrative data to identify the causal effect of traffic stops on voter behavior. The use of administrative data marks an important step forward in our understanding of how low-level contact with the criminal legal system structures political participation. Past work looking at the individual-level effects of low-level contact has relied on survey or interview data (e.g., Walker Reference Walker2014; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010). Existing research allows for the testing of specific psychological mechanisms and personal interpretations of criminal legal contact but does not allow us to generalize more broadly. As Weaver and Lerman (Reference Weaver and Lerman2010, 821) note, it may also introduce measurement bias. Our analysis investigates actual voting behavior following actual traffic stops, not reported voting behavior or reported exposure to a traffic stop. The administrative data therefore allow us both to sidestep reporting error and to observe the behavior of a quarter-million individuals stopped over a six-year period—a far larger pool than even the most robust surveys.

We use individual-level traffic stop data from Hillsborough County, Florida, to identify the turnout patterns of voters who were stopped between the 2012 and 2018 elections. By matching individual voters who were stopped to similar voters who were stopped at later points and running a difference-in-differences model, we estimate the causal effect of these stops on turnout. This borrows from the logic of regression discontinuities in time: conditional on observable characteristics and unobservable factors associated with being ticketed, the timing of the stop on either side of election day is essentially as-if random. We find that being stopped reduces the chance that an individual will turn out in the subsequent election but that this effect is smaller for Black voters in the long run.

We demonstrate that traffic stops—the most widespread form of police contact in America—substantially reduce the turnout of non-Black American voters but reduce Black voter turnout to a smaller degree. More specifically, we find temporal variation in the effect of stops on Black voter turnout: Black voters stopped shortly before an election are demobilized to a greater extent than are non-Black voters, but as more time passes between stops and the election of interest, the treatment effect becomes comparatively smaller for Black voters. Our findings complicate existing theories of how criminalization politically socializes Americans, and Black Americans in particular (Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010). Additionally, although many forms of criminalization have been found to contribute to a well-documented subjective experience of alienation or group-level exclusion among Black Americans (Ang et al. Reference Ang, Bencsik, Bruhn and Derenoncourt2021; Bell Reference Bell2017; Desmond, Papachristos, and Kirk Reference Desmond, Papachristos and Kirk2016; Reference Desmond, Papachristos and Kirk2020; Stuart Reference Stuart2016; Zoorob Reference Zoorob2020), our contribution emphasizes the need for further research regarding how different forms of criminalization affect group-level perceptions of government and resultant political behaviors. Our findings are relevant for interdisciplinary scholars of crime, race, politics, municipal finance, and policing.

Theory

How Police Stops Might Influence Turnout

Learning about one’s “place in the system” takes place over long periods. Could isolated police stops that do not require sustained contact with the criminal legal system affect the political behavior of Americans? To ground our expectations, we turn first to recent work exploring the effect of high-level contact with the criminal legal system on political behavior. We then consider what this literature can and cannot say about expected effects of police stops on voting.

A growing body of work has explored the effects of criminal legal contact on political participation. Some scholars find large depressive effects from incarceration (Burch Reference Burch2011), whereas others argue that any negative effects are smaller or mixed (e.g., Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Huber, Meredith, Biggers and Hendry2017; White Reference White2019b). Other work has explored the “spillover” effects of incarceration, finding that the political behavior of family members (Walker Reference Walker2014; White Reference White2019a) and neighbors (Burch Reference Burch2014; Morris Reference Morris2021b) can be influenced by indirect contact with incarceration, and these effects might be quite durable (Morris Reference Morris2021a). The one project that has used administrative data to explore the political implications of low-level police contact is Laniyonu (Reference Laniyonu2019), which finds mixed effects of the Stop-Question-and-Frisk practice on neighborhood-level turnout in New York City, though the strength of the causal design is limited. Thus, the literature generally agrees that contact with the criminal legal system reduces political participation.

The existing literature broadly groups the depressive mechanisms into two categories: “resource” and “political socialization” (see White Reference White2019b, 312). Classic political science literature indicates that citizens with more resources are more likely to participate (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995); these resources are undermined by the time and financial resources individuals and family members devote to dealing with a felony conviction. Although higher-level contacts come with higher costs than an average police stop, the resource story could extend to some of these less-disruptive contacts with the criminal legal system. If a ticket leads to a suspended driver’s license, the initial stop can snowball into a much bigger life event that could jeopardize employment or lead to shorter stints of incarceration. Searches conducted during traffic stops may also lead to arrest if a police officer finds contraband in the vehicle. These cases might have consequences more akin to those associated with a brief period of incarceration that can also threaten employment. Nevertheless, the average traffic stop is certainly less disruptive than the average period of incarceration, likely demanding fewer resources than other forms of contact.

Literature on political socialization argues that citizens’ perceptions of and behavior with respect to government are heavily determined by routine interactions with state apparatuses and government officials. As Soss and Weaver (Reference Soss and Weaver2017) argue, “interviewees have looked, not to City Hall, Congress, or political parties, but rather to their direct experiences with police, jails and prisons, welfare offices, courts, and reentry agencies as they sought to ground their explanations of how government works, what political life is like for them, and how they understand their own political identities” (Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017, 574). To that end, Lerman and Weaver (Reference Lerman and Weaver2014) found that citizens nearly uniformly react negatively to criminal legal contact: trust in government and willingness to vote decrease as individuals progress through increasingly intense levels of contact (questioned by police, arrested, convicted, incarcerated; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010). This withdrawal is not limited to political participation but extends to other forms of civic life as well (e.g., Brayne Reference Brayne2014; Remster and Kramer Reference Remster and Kramer2018; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020). Weaver, Prowse, and Piston (Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020) describe this form of self-preserving withdrawal from public institutions as a “strategic retreat.”

These findings can be situated in a process that sociologist Monica Bell (Reference Bell2017) calls “legal estrangement,” which captures criminalized Americans’ negative perceptions of government as well as the historical conditions that produced them. Research on legal cynicism has found that public perceptions of abusive police practices can reduce willingness to report crimes or cooperate with law enforcement (Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014). The “hidden curriculum” (Justice and Meares Reference Justice and Meares2014; Meares Reference Meares2017) of the criminal legal system thus teaches Americans about their identities as citizens—even parts of their identities that have little to do with policing or incarceration.

This literature has given scholars far greater insight into the participatory consequences of incarceration, but it says little about the effects of lower-level contact with the criminal legal system on political participation. Yet far more Americans have low-level contact with the police than will ever spend a night behind bars: just under 20 million Americans experience a traffic stop each year, whereas approximately 10 million Americans are arrested and jailed each year (Harrell and Davis Reference Harrell and Davis2020; Zeng and Minton Reference Zeng and Minton2021). A police stop might be among a voter’s first interactions with the criminal legal system; thus, stops may be important for political socialization precisely because they are an early stage in the criminalization process.

Recent work shows that when threats are made newly salient, individuals can update their behavior (Hazlett and Mildenberger Reference Hazlett and Mildenberger2020; Lujala, Lein, and Rød Reference Lujala, Lein and Rød2015; Mendoza Aviña and Sevi Reference Mendoza Aviña and Sevi2021; Skogan Reference Skogan2006). Thus, although humans are generally bad at incorporating new information into their worldviews (e.g., Lord, Ross, and Lepper Reference Lord, Ross and Lepper1979), police stops—which are often considered unfair (Snow Reference Snow2019)—might provoke a rethinking of the police and government and a subsequent updating of political behavior. Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Huber, Meredith, Biggers and Hendry2017) note in their study that the participatory consequences of incarceration might be small because incarceration “is an outcome that often follows a long series of interactions with the criminal justice system” (1145). In other words, much of what the criminal legal system “teaches” might have already been learned by the time an individual is sent to prison. Someone who is stopped by the police, however, might have had fewer negative interactions with the state, resulting in comparatively larger turnout effects relative to the size of the disruption.

Additionally, the fact that traffic stops affect a larger and systematically less marginalized group of Americans compared with incarceration could help explain the relationship between stops and voting.Footnote 1 Traffic stops might be the primary way some of these Americans learn about the criminal legal system. If these Americans have not already “learned” about the system from their neighborhoods or family members, the political consequences of such newly gleaned knowledge might be large.

In short, although past work has argued that criminal legal contact influences participation through both “resource” and “socialization” mechanisms, we contend that the latter are particularly important for our study. The relatively small resource disruptions coupled with outsized opportunities for new learning about the state likely means any turnout effects will operate primarily through avenues associated with socialization (that is, legal estrangement and strategic retreat). Unfortunately, our empirical approach cannot formally adjudicate between the relative importance of the mechanisms. Future work should take up this question.

Potential for Racially Disparate Effects

In addition to testing the potentially demobilizing effect of traffic stops on voter turnout, we ask whether this effect is different for Black voters, who are disproportionately subjected to traffic stops (see Table 1) as well as criminal legal contact more broadly.

Table 1. Balance Table

We propose that two causal mechanisms could distinctly shape the treatment effects for Black voters. First, we expect that due to greater baseline criminal legal contact, Black voters could have “less to learn” from stops in our analysis, thus leading to a weaker overall turnout effect. Separate from this “learning” process, it’s possible that a comparatively stronger initial psychological salience of traffic stops could lead to a larger demobilizing effect for Black voters in the short term. Thus, as the short-term demobilizing effect of a stop fades, the treatment effect returns to a baseline of “less learning.”

The average Black American knows far more about the criminal legal system than the average non-Black American due to racial disparities in policing and incarceration (Lee et al. Reference Lee, McCormick, Hicken and Wildeman2015). In the previous section, we argued that police stops might reduce turnout because motorists stopped by the police might gain “new” information about the police and government more generally from this stop. Given that Black Americans have higher baseline exposure to the criminal legal system, the modal police stop could result in less new knowledge and provoke a smaller reduction in political participation.

Still, traffic stops differ in meaningful ways for Black and non-Black Americans. These differences could increase the psychological salience of stops for Black voters, especially in the immediate aftermath of a stop. As Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub (Reference Baumgartner, Epp and Shoub2018) note, Black Americans are more likely than are whites to receive both “light” (i.e., a warning without a ticket) and “severe” (i.e., arrest) outcomes from a traffic stop. Although this may seem paradoxical at first, the authors explain: “while many might rejoice in getting a warning rather than a ticket, the racial differences consistently apparent in the data suggest another interpretation for black drivers: even the officer recognized that there was no infraction” (88). Goncalves and Mello (Reference Goncalves and Mello2021) find that Florida Highway Patrol officers are more likely to give “discounted” tickets to white motorists than to Black or Hispanic motorists, and although Black drivers are also more likely to be searched and arrested, they are less likely to be found with contraband (Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub Reference Baumgartner, Epp and Shoub2018). Similarly, Epp, Maynard-Moody, and Haider-Markel (Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014) argue that traffic stops are particularly instructive for Black Americans, as pretextual traffic stops politically socialize Black voters to the specific context of discriminatory police ticketing.

The Black Lives Matter movement has increased the salience of structural racism in policing across the country, as have the tragic stories of individuals like Philando Castile who was killed during a police stop. Increasing municipal reliance on fines and fees creates more opportunities for police violence, and routine interactions with the police are also more likely to turn deadly for Black Americans than for others (Brett Reference Brett2020; Levenson Reference Levenson2021). Indeed, Alang, McAlpine, and McClain (Reference Alang, McAlpine and McClain2021) find that Black Americans experience “anticipatory stress of police brutality” (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety) to a degree that white Americans do not. Thus, even if an individual police stop for a Black American is relatively unremarkable on its own, the background context that the interaction could have turned deadly is likely to increase the psychological salience of traffic stops for Black drivers. We expect that traffic stops that immediately precede an election should be more demobilizing.

These apparently competing mechanisms can be reconciled by examining temporal variation in the effect of traffic stops on voting. We expect to find that the psychological salience of a police stop will disproportionately reduce the turnout of Black Americans in the short-term. Over the longer-term—when the immediacy of the police stop fades—we expect smaller turnout effects for Black Americans, potentially because they have less to learn from a given stop (pushing the treatment effect toward zero).

Data and Design

We estimate the causal effect of traffic stops on voter turnout using individual-level administrative data from Hillsborough County, Florida (home to Tampa). The empirical estimand is the turnout gap between registered voters in Hillsborough County who have recently been stopped and voters who will be stopped in a future period, conditional on similar turnout in past elections and similar demographic characteristics. We exploit unusually detailed public data, which allows for a precise causal analysis that cannot be conducted in counties that do not provide ticketing records with personally identifiable information or states that do not include self-reported race data in the voter file.

Replication materials are available in the American Political Science Review Dataverse (Ben-Menachem and Morris Reference Ben-Menachem and Morris2022). Out of concerns for privacy and due to the use of a proprietary geocoder, we do not post individually identifiable data.

Hillsborough County

The Hillsborough County Clerk makes information publicly available about every traffic stop in the county going back to 2003. These data include the name and date of birth of the individual stopped, the date of the offense, and other information.Footnote 2

Beyond the uniqueness of this dataset, Hillsborough County is a jurisdiction of substantial theoretical interest. The county is home to Tampa, where the Tampa Police Department has maintained “productivity ratios” for officers since the early 2000s (Zayas Reference Zayas2015a). Each officer’s number of arrests and tickets was divided by their number of work hours, and this ratio was used in performance evaluations. In 2015, written warnings were added to this ratio, and scrutiny from the Tampa Bay Times may have reduced the importance of the ratio in officer evaluations. Regardless, the department’s de facto ticketing quotas were active during our study period, and voters may have been aware of them as well. Earlier that year, the same newspaper reported on the police department’s practice of relentlessly ticketing Black bicyclists (Zayas Reference Zayas2015b). This investigation catalyzed a US Department of Justice investigation and report, requested by Tampa’s mayor and police chief.

Ticketing has also been expressly politicized in Tampa: Jane Castor, who was elected mayor in 2019, was Tampa’s police chief until 2015 and publicly defended her department’s disproportionate ticketing of Black bicyclists before retracting her defense ahead of her mayoral campaign (Carlton Reference Carlton2018). Her opponent, banker and philanthropist David Straz, campaigned against red-light cameras and focused his outreach in Tampa’s Black communities (Frago Reference Frago2019).Footnote 3

Design and Identification Strategy

To identify stopped voters, we match the first and last names and dates of birth from the stop data against the Hillsborough County registered voter file. Meredith and Morse (Reference Meredith and Morse2014) develop a test for assessing the prevalence of false positives in administrative record matching. We present the results of that test in section 1 of the Supplementary Materials (SM). We likely have a false-positive match of around 0.03%, a figure we consider too low to affect our results meaningfully.

Using a single post-treatment snapshot of the voter file can result in conditioning on a post-treatment status (see Nyhan, Skovron, and Titiunik Reference Nyhan, Skovron and Titiunik2017). Instead, we collect snapshots of the voter file following each even-year general election between 2012 and 2018. We thus observe virtually all individuals who were registered to vote at any time during our period of study. Unique voter identification numbers allow us to avoid double-counting voters who are registered in multiple snapshots. We retain each voter’s earliest record and geocode voters to their home census block groups. We remove tickets issued by red-light cameras, which Hillsborough County only begins including in the data toward the end of our study period.

By matching the police stop and voter records, we identify all voters who were stopped between the 2012 and 2020 general elections. Voters stopped between the 2018 and 2020 elections serve only as controls. We collect self-reported information regarding the race of each voter from Florida’s public voter file rather than the police stop data. Voters are considered “treated” in the general election following their stop. Treated voters are then matched to a control voter using a nearest-neighbor approach, with a genetic algorithm used to determine the best weight for each characteristic (Sekhon Reference Sekhon2011).Footnote 4 Control voters are individuals who are stopped within the two years following the post-treatment election of the treated voters. Put differently, if a voter is stopped between 2012 and 2014, their control voter must be an individual stopped between the 2014 and 2016 elections. A voter cannot both be a treated and control voter for the same election; therefore, someone stopped between the 2012 and 2014 elections and again between the 2014 and 2016 elections cannot serve as a control for anyone stopped between 2012 and 2014. We limit the target population to voters who are stopped at some point in order to account for unobserved characteristics that might be associated with both the likelihood of being ticketed and propensity to vote.

We match voters on individual-level characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, party affiliation, age, and number of traffic stops prior to the treatment period) and block group-level characteristics from the 2012 five-year ACS estimates (median income, share of the population with some college, and unemployment rate). We match exactly on the type of ticket (civil/criminal infraction, whether they paid a fine, and whether they were stopped by the Tampa Police Department) to ensure that treated and control voters receive the same treatment. Finally, we match treated and control voters on their turnout in the three pre-treatment elections. Matching is done with replacement, and ties are not broken. This means that some treated voters have multiple controls; the regression weights are calculated to account for this possibility.

We assume that after controlling for observable characteristics, past turnout, and the unobservable characteristics associated with experiencing a traffic stop, the timing of the stop is effectively random. This is conceptually similar to the regression discontinuity in time framework, and we assume that any turnout difference between the treated voters and their controls is the causal effect of a police stop on turnout. Our overall turnout effects are robust to weaker assumptions: as we show, we uncover large, negative turnout effects even when we force voters stopped shortly before the election to match to voters stopped shortly afterwards.

Our analytical design incorporates matching in a traditional difference-in-differences model in order to improve the credibility of our identification assumptions. Leveraging pre-treatment turnout allows us to estimate the difference-in-differences model, and the matching procedure improves the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption by reducing salient observed differences between the treated and control voters. For a more detailed discussion of how matching can improve on traditional difference-in-difference approaches when using panel data, see Imai, Kim, and Wang (Reference Imai, Kim and Wang2021).

We then estimate the following equation:

Individual i’s turnout (v) in year t is a function of the year and whether they were stopped by the police. In the equation, β1 measures the historical difference between treated voters and their controls, β2 measures whether turnout increased for controls in the first election following the treated voter’s stop, and β3 tests whether turnout changed differently for treated voters than their controls in the election following their police stop. So, β3 will capture the causal effect of a police stop on voter turnout; it is the unit-specific quantity measured in our empirical estimand (Lundberg, Johnson, and Stewart Reference Lundberg, Johnson and Stewart2021). The term β4Yeart captures year fixed-effects depending on the timing of the police stop, and the matrix δZi contains the individual- and neighborhood-level characteristics on which the match was performed, included in some of the models. In some models, we also interact the treatment and period variables with a dummy indicating whether the voter is Black to determine race-specific treatment effects.

Results

We begin by plotting the turnout of treated and control voters under different analytical approaches in Figure 1. The first row plots the turnout of all treated and control voters without any matching. In the second row, we plot the turnout of treated voters and matches selected when we exclude pre-treatment turnout from the matching procedure. In the final row, we present the controls selected when pre-treatment turnout is included in the match.Footnote 5 The first election following a treated voter’s stop is denoted as t = 0, and the years in which t is less than zero are the periods prior to the stop.

Figure 1. Turnout, Treated and Control Voters

Note: Treatment occurs in the shaded band. The full regression tables are available in section 3 of the SM.

All three approaches demonstrate the same general treatment effect. In the first two approaches, treated voters consistently have slightly higher turnout rates than do the controls prior to the treatment; the difference between these two groups disappears in the election following the stop of the treated voter (visual indication of a negative treatment effect). Both the “raw” difference-in-differences approach and the approach excluding the pre-treatment outcomes from the match exhibit a potential violation of the parallel trends assumption (particularly for Black voters), so we adopt the final specification as our primary model. However, our negative treatment effects are not simply an artifact of our modeling decisions. The full specification for the first row of Table 1 (with and without matching covariates included) can be found in columns 1 and 2 of Table A7 in the SM, and those corresponding to the approach where prior turnout is not included can be found in columns 3 and 4 of the same table.

In Table 1 we present the results of the matching algorithm using our preferred specification incorporating pre-treatment turnout. As the table demonstrates, the selected control voters are very similar to the treated voters.

It is worth noting that voters who were stopped between 2012 and 2020 were far more likely to be Black and male than the general electorate and live in census block groups with moderately lower incomes.

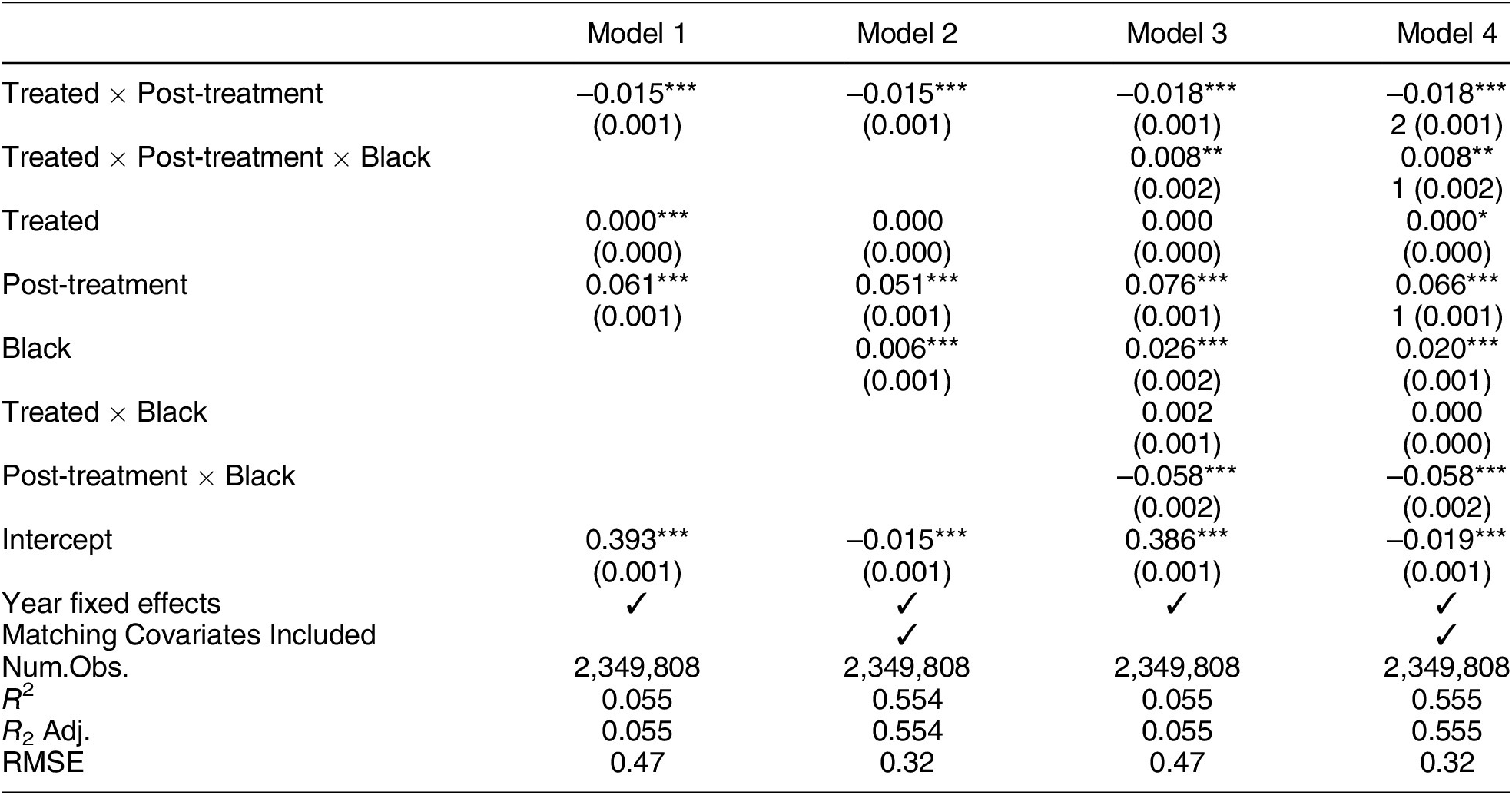

Table 2 formalizes the final row of Figure 1 into an ordinary least squares regression. The full models from Table 2 with coefficients for the matched covariates can be found in Table A6 of the SM, and full specifications for 2014, 2016, and 2018 individually can be found in Tables A3–A5, respectively. Models 1 and 2 show our overall causal effect, and models 3 and 4 allow for the possibility that a stop differentially mobilizes Black voters. In models 1 and 3, we include only the treatment, timing, and race dummies, whereas the full set of covariates used for the matching procedure are included in models 2 and 4. The empirical estimands are Treated

![]() $ \times $

Post Treatment and Treated

$ \times $

Post Treatment and Treated

![]() $ \times $

Post Treatment

$ \times $

Post Treatment

![]() $ \times $

Black. In models 1 and 2, the coefficient on Treated

$ \times $

Black. In models 1 and 2, the coefficient on Treated

![]() $ \times $

Post Treatment measures the overall treatment effect, and in models 3 and 4 it measures the treatment effect for non-Black voters. The coefficient on Treated

$ \times $

Post Treatment measures the overall treatment effect, and in models 3 and 4 it measures the treatment effect for non-Black voters. The coefficient on Treated

![]() $ \times $

Post Treatment

$ \times $

Post Treatment

![]() $ \times $

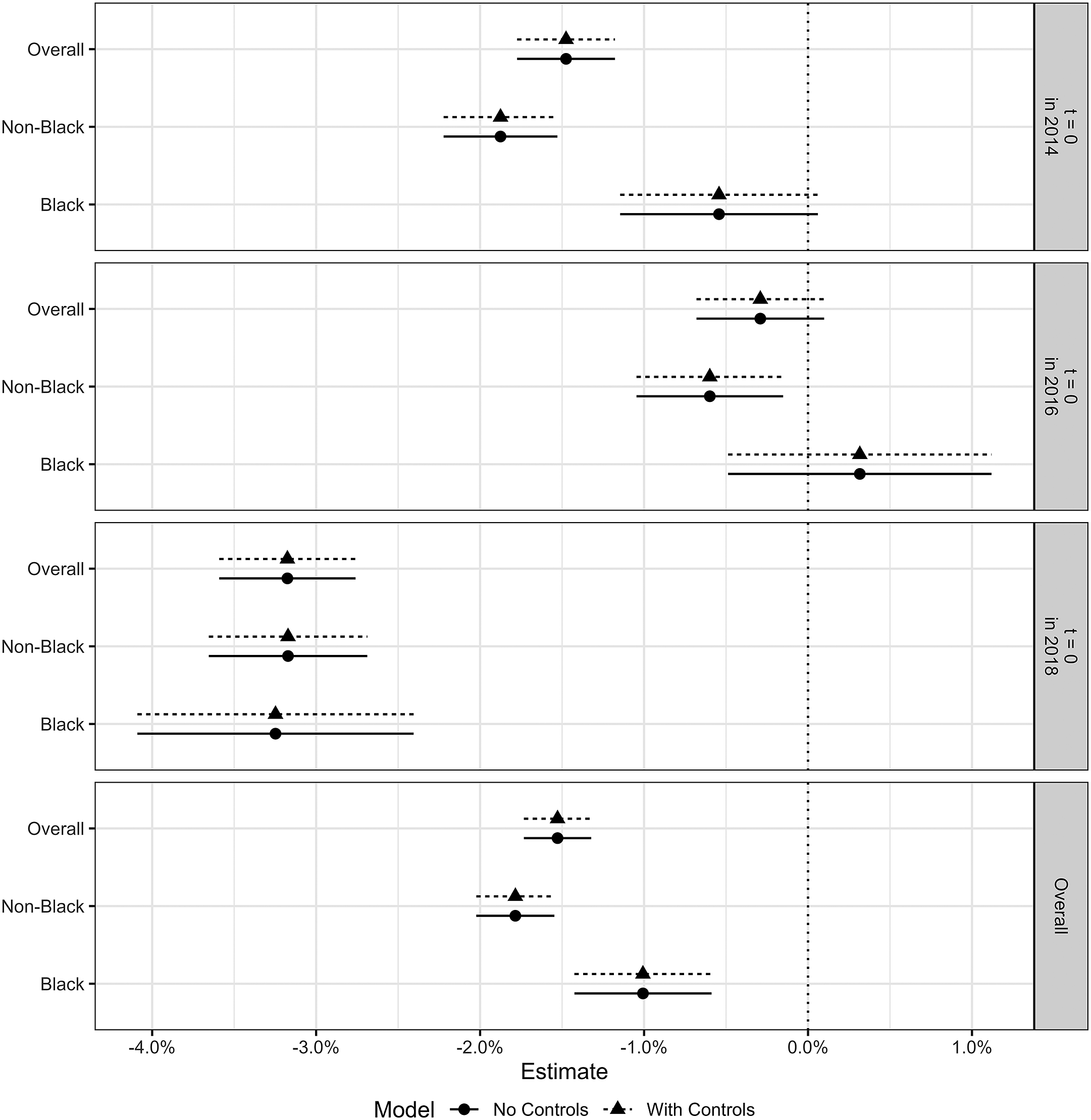

Black measures any effect for Black voters beyond the effect measured for non-Black voters. By multiplying the Black dummy through the treatment and timing dummies, models 3 and 4 become triple-difference (or difference-in-difference-in-differences) models. In Figure 2 we plot the coefficients for each of the individual years as well as the overall treatment effect. These models follow the same logic as Table 2, where we show the point estimates with and without the matched covariates included. The full models shown in Figure 2, with coefficients for the matched covariates, can be found in Tables A3–A6 of the SM.

$ \times $

Black measures any effect for Black voters beyond the effect measured for non-Black voters. By multiplying the Black dummy through the treatment and timing dummies, models 3 and 4 become triple-difference (or difference-in-difference-in-differences) models. In Figure 2 we plot the coefficients for each of the individual years as well as the overall treatment effect. These models follow the same logic as Table 2, where we show the point estimates with and without the matched covariates included. The full models shown in Figure 2, with coefficients for the matched covariates, can be found in Tables A3–A6 of the SM.

Table 2. Overall Treatment Effect

Note: Dependent variable: individual-level turnout; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Coefficient Plot: Effect of Stops on Turnout (with Matching)

As both Figure 2 and Table 2 make clear, traffic stops meaningfully depressed turnout. In models 1 and 2, the estimated overall treatment effect is -1.5 percentage points (pp). In models 3 and 4, we can see that traffic stops were less demobilizing for Black individuals than for others—non-Black turnout was depressed by 1.8 percentage points, whereas the negative effect was just 1.0 for Black individuals. Although the treatment effect is still substantively quite large for Black individuals, Hillsborough County Black voters’ turnout in federal elections was not as negatively affected by police contact as that of non-Black individuals. It is also clear that midterm turnout is more affected by these stops. The negative effect is statistically significant in all years for non-Black residents but much smaller in 2016 (-0.6 pp) than in 2014 (-1.9 pp) or 2018 (-3.2 pp).

Testing the Temporal Durability of the Effect

In the section above, we present the average effect of a police stop on turnout for treated voters. This effect is averaged across all voters stopped in the two years prior to a federal election. Although using such a large pool of treated and control voters allows for better covariate balance within pairs, such wide windows around each election give us no insight into the temporal stability or variability of the treatment effect. Moreover, treated and control pairs might have been stopped at very different points; a voter stopped almost two years before an election can be paired with someone stopped two years after that election, meaning there were four years between the police stops. These voters might differ in important, unobservable ways.

Here, we explore the temporal component of our primary results by rerunning our matching process on a variety of different windows around the elections. In the most conservative approach, we force voters stopped in the month before an election to match with voters stopped in the month after the election; we then gradually expand this window, allowing voters stopped in the two months before the election to match to those stopped in the two months afterwards until we reach the two-year period used in our main model. The left-hand side of Figure 3 plots the treatment effect for Black voters depending on the window used; the right-hand side shows these estimates for non-Black voters. The full regression outputs for these models can be found in Tables A8–A11 in the SM.

Figure 3. Treatment Effect over Time

The treatment effects for Black voters show strong temporal variability. In fact, when looking at voters stopped shortly before an election, police stops are more demobilizing for Black than non-Black voters. This relationship flips by the time the full pool of voters is included. The treatment effect decreases from roughly -3 to -1 pp over the range of windows.

Although the administrative data prevent us from exploring the psychological mechanisms at play, and their temporal durability, this finding is consistent with our theoretical expectations: a police stop might be more psychologically salient—and thus more demobilizing—for Black voters in the short term. Once the immediate salience of the stop fades, it’s possible that baseline knowledge about the criminal legal system mitigates longer-term effects, thus explaining the smaller effects in the models with longer windows. Of course, future work should explore these possibilities directly.

The right-hand side of the plot shows far less temporal variation in the magnitude of the treatment effect for non-Black voters. Although non-Black voters are most demobilized if stopped in the month before the election, the overall trend is fairly stable (if moderately downward sloping).

Discussion

Although existing sociological and political science literature has examined the rise and collateral consequences of criminalization on political socialization, no study has investigated the causal relationship between traffic stops and voter turnout using individual-level administrative data.

Given how widespread police stops are and their relationship to racial injustice, their political implications demand close study. What we find advances our understanding of how lower-level police contact affects political participation. We find that traffic stops reduce turnout among non-Black voters, with a smaller negative effect for Black voters. We also find substantial temporal variation in the treatment effect for Black voters: in the short term, stops appear to be more demobilizing, but as time passes they become comparatively less demobilizing. We conclude that the political consequences of police stops are unique for Black Americans—and that they are, on balance, less demobilizing for Black Americans than for others. This joins other recent research finding that small-scale interventions like Get-Out-the-Vote encouragements have smaller effects on Black Americans (Doleac et al. Reference Doleac, Eckhouse, Foster-Moore, Harris, Walker and White2022), perhaps because their opinions on the criminal legal system are more firmly set. Scholars ought to explore more specifically when and what sorts of interactions produce larger effects for Black Americans and when these effects are smaller.

Our findings have several implications for political science scholarship. Although existing literature suggests that the most disruptive forms of criminal legal contact (i.e., criminal convictions and incarceration) consistently discourage voting (Burch Reference Burch2011; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; White Reference White2019b), research regarding police stops has produced more mixed results (Laniyonu Reference Laniyonu2019). We extend political socialization theory to traffic stops, the most common form of police contact in America, and find that police traffic stops generally reduce turnout. For Black voters, however, our findings suggest that traffic stops are less demobilizing, a contrast with existing scholarship wherein more disruptive forms of criminalization discourage Black voters more than non-Black voters. Our findings constitute new evidence in support of our theory that police stops are distinct from other forms of criminal legal contact and therefore catalyze different political behaviors among Black voters, who are disproportionately affected by both ticketing and criminalization in general.

It is worth considering the implications of a study focused only on the behavior of individuals who were registered to vote at some point during the study period. Registration is itself an act of political participation; therefore, our study population is systematically more engaged in electoral politics than the general population. This supports our argument that traffic stops are an important form of political socialization. More specifically, if voters in the target population already understood the ballot box as a tool they could use to change political outcomes or at least make their voices heard, structurally, it stands to reason that the effect of traffic stops is potent enough to overcome longer-term attitudes and behaviors with respect to government. In other words, even if the observed point estimates are small, the fact that registered voters’ turnout is depressed by traffic stops justifies our contention that traffic stops are politically salient events. This focus on registered voters likely makes our results conservative: we cannot capture the lost participation of individuals who would have registered and voted if they were not stopped by the police.

Focusing on the turnout of registered voters also misses other important political behavior that future work should explore. As Walker (Reference Walker2020b) suggests, stopped Black individuals may be politically mobilized for activities other than voting not observed in this study, such as contacting elected representatives or volunteering for campaigns. The fact that we find that stops produce a negative turnout effect for Black voters does not rule out the possibility that stopped Black motorists could be more likely to engage in nonvoting political activities. Christiani and Shoub (Reference Christiani and Shoub2022) also find that traffic stops and tickets can catalyze nonvoting political participation, but observe stronger positive effects among people who have better perceptions of police (i.e., white people).

Existing political science theory regarding “injustice narratives” could provide an alternate or complementary framework for interpreting our results. Recent work from Hannah Walker (Reference Walker2020a; Reference Walker2020b) argues that police contact could lead to a mobilizing effect if voters understand criminal legal contact in the context of a narrative of racial injustice. Although she finds that this sense of injustice is especially likely to increase political participation in nonvoting ways (such as attending a protest or signing a petition) and particularly salient following proximal rather than personal contact, the injustice narrative mechanism could also affect voter turnout following personal contact. Thus, the temporal variation we found could occur because the experience of personal contact is eventually incorporated into an “injustice narrative” because Black Americans who are socially proximate to the stopped individual end up also being subjected to criminal legal contact between the stop and the election of interest, or both.

The injustice narrative mechanism could provide another justification for the reversal of the initially more demobilizing effect of stops on Black voter turnout—perhaps some subset of stopped Black voters end up affirmatively mobilized several months after the stop, thus explaining the overall comparatively smaller demobilizing effect observed in our results. Unfortunately, the administrative data do not allow for a compelling test of this hypothesis; most information about voters in our analysis is at the census tract level, not individual level, and we lack information about activities such as participation in community organizations that Walker suggests might mediate the relationship between criminal legal contact and political behavior. Ultimately, we are sensitive to the fact that although administrative data provide real-world evidence of actual behavior, such data limit our ability to understand the causal mechanisms at play. This means that although we demonstrate that police stops are demobilizing, future work must further investigate how stops are interpreted by individuals and translated into political behavior.

Future work should explore these and other questions. Particular attention should be paid to variation within the Black community. When is this sort of contact demobilizing? For whom? Can organizers build on this potential for broad-based political action? We were unable to test whether what we observed was simply decreased demobilization or whether some subgroups of the Black population were mobilized but others were demobilized. Scholars should also investigate the interactive effects of criminal legal contact, asking whether police stops result in different political behavior for formerly incarcerated individuals than individuals with no other contact with the system. Finally, this project looks only at voting, so scholars should continue exploring whether low-level contacts also shape other sorts of engagements with the state.

Although we have contributed new evidence suggesting that police stops may not demobilize Black voters to the same extent as they do non-Black voters, we emphasize that this finding does not redeem or justify exploitative ticketing practices. Black Americans already suffer from disproportionate police contact and the racial wealth gap, and revenue-motivated ticketing only increases the burden on Black communities nationwide. Policy makers should work to ensure that Black Americans no longer have to struggle to enjoy the same political power as whites—to that end, the current trend of voting rights restriction policies across the country is especially pernicious. Even if some Black Americans understand the ballot box as one tool they can use to limit the state’s power to exploit and harm them, policy makers should still feel an obligation to support voting rights protections and stop disproportionate ticketing in Black communities.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001265.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YGTFBW. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the text.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors contributed equally. We are grateful for feedback we received after presenting earlier versions of this work at the 2021 American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, the 2021 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, and the Justice Lab at Columbia University. We would like to thank Hannah Walker, Bruce Western, Flavien Ganter, Sam Donahue, Gerard Torrats-Espinosa, Joshua Whitford, Brittany Friedman, Brendan McQuade, Tarik Endale, Van Tran, Brennan Center colleagues, and the reviewers and editor for their thoughtful feedback.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in their research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was deemed exempt from review by the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.