In the long-term history of wetlands, the sixteenth century represents a turning point as at that time very large funds were injected into a new system of drainage.Footnote 1 In the Low Countries and in northern Italy more than anywhere else, the conquest of the wetlands turned into an extensive business.Footnote 2

The change was particularly marked in Holland, where people were obliged to manage the consequences of the intensive mining of peat which had occurred during the Middle Ages.Footnote 3 To drain the lakes created by the resulting subsidence, the Dutch employed new techniques, using windmills to divert water into canals and rivers. The spread of this model, called the boezem system, enabled the extension of agricultural land and the growth and urbanization of the population. It marked the beginning of a new relationship between human societies and marshes, as the drainage work was supported by the central political authorities and financed by capitalist groups.Footnote 4 That development was enhanced in the last twenty years of the sixteenth century when refugees from Flanders and Brabant put their money into drainage projects in the northern Netherlands.Footnote 5

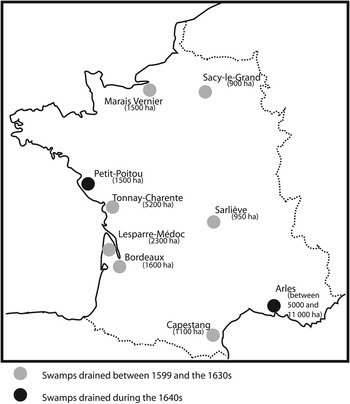

As early as the 1580s, the water-management skills of the Dutch had become a model throughout Europe. The role of Dutchmen in the draining of wetlands could be documented in such very different regions as Britain, Germany, Russia, Italy, and France.Footnote 6 In England, Humphrey Bradley, a Dutch engineer and a native of Bergen op Zoom in Brabant, came to drain the Fens in the 1580s.Footnote 7 Soon after, Bradley was called to France, where he launched a wave of land reclamation. From 1599 to the end of the 1650s, the intervention of foreign engineers and financiers was continuous. At least 12 swamps were drained and no fewer than 150 and perhaps as many as 260 square kilometres of wetlands were converted to arable lands or meadows. That surface area can be compared to the 1,115 square kilometres which the Dutch, who in contrast to the French were short of arable land, drained in the meantime for themselves.Footnote 8

The draining of French wetlands was thus a major event, and can usefully be analysed in its European context. Indeed, the alliance between the French monarchy and foreign merchants and bankers who were interested in international trade was the only means to carry out drainage projects in France, so the draining of French marshes was strongly embedded in the internationalization of the seventeenth-century economy. Although the French had money to invest, Dutch bankers were more readily able to provide funds, resources, and skills. As the main investors were not natives of the regions where the land reclamation had taken place, the drainage operations caused conflicts which reveal the socio-political significance of land reclamation. Moreover, as both the cases of Arles (Provence) and Petit Poitou (Poitou) show, such projects launched by Henri IV had a far-reaching environmental impact.Footnote 9

Land Reclamation In Seventeenth-Century France And The Economic Development Of Amsterdam

In 1583, Henri III granted an entitlement to drain the lake of Pujaut (Gard, Languedoc) in southern France.Footnote 10 In 1599, Henri IV continued the policy and changed the scale of its application by promulgating an edict which promoted land reclamation throughout the kingdom.Footnote 11 He gave Humphrey Bradley the power to drain all of France’s lakes and marshes. That same year, Bradley joined Conrad Gaussen, a Dutch merchant who had settled in Bordeaux, in order to drain the marshes there and those of Lesparre, located in the low estuary of the Gironde (Guyenne).Footnote 12 In 1600, Bradley attempted to extend his activities to the French Atlantic coast and started to drain the Tonnay-Charente marshes (Charente-Maritime). Despite the support of the monarchy and the creation of a very favourable legal framework, Bradley could not cope alone with the opposition he had to face.Footnote 13 He had to contend with former users of swamps, and he barely managed to raise enough money to finance his projects.

In 1605, therefore, he set up an association with the Comans brothers and François de la Planche, or van der Planken.Footnote 14 Even though the first contract does not mention him, Hieronimus van Uffelen was also involved in this company.Footnote 15 The Comans and de la Planche were natives of Brabant, and ultra Catholic. They had been called by Sully, then prime minister and Surintendant des finances, to develop tapestry manufacturing in Paris in the hope that it would limit textile imports from the Low Countries.Footnote 16 Settled in Paris in the early seventeenth century, they quickly extended their activities to include the leather and grain trades.Footnote 17 In the Parisian notaries’ archives, it appears that they were associated with Van Uffelen, who came from Antwerp, in various businesses.Footnote 18

In 1585, his family had moved to Amsterdam, where they traded in copper and lead as well as in drapery. Their Russian trade flourished and two family members established themselves in Venice, where they acted as agents. Van Uffelen also participated in overseas trade by buying shares in the Dutch East India Company.Footnote 19 The family’s integration into Amsterdam’s merchant elite was strengthened when Jacomo van Uffelen married Maria van Erp in 1616. She was the daughter of a famous copper trader, Arent van Erp,Footnote 20 and the sister-in-law of Pieter Cornelisz Hooft, a major trader in herring, oil, and grains. Hooft was one of the first shareholders of the VOC and was many times mayor of Amsterdam.Footnote 21 Thus, from the beginning, the French land reclamations launched by Henri IV had involved members of the commercial elite of Amsterdam who had come originally from the Brabant region.

Those Flemish and Brabant capitalists were backed by the French aristocracy as early as 1605, thus providing a strong political network. Jean de Fourcy was the Surintendant des bâtiments du roi, in charge of the administration of the royal buildings, and a member of the Conseil d’État, an increasingly powerful instrument of central government.Footnote 22 Originally close to Sully, he became a “creature” of Richelieu as early as the 1610s. Antoine Ruzé d’Effiat was Jean de Fourcy’s brother-in-law and became Surintendant des finances in 1625.Footnote 23 Nicolas de Harlay was a former Intendant des bâtiments du roi and a former ambassador of Henri III and Henri IV. Until 1639, the association remained stable, despite the deaths of Jean de Fourcy in 1625 and Antoine Ruzé d’Effiat in 1631. For instance, in 1634, Henry de Fourcy, son of Jean, and Luca van Uffelen, son of Hieronimus, were still involved in a joint business to export grain to Malta.Footnote 24 Furthermore, the owners of French-drained lands used the network of Dutch merchants to sell the produce from their new properties at favourable prices.

For more than thirty years, the draining of the French marshes relied on the association of three different groups: French aristocrats and financiers, foreign capitalists, and the engineer Humphrey Bradley. The scheme worked effectively because of the shared interests of French financiers and capitalists and merchants from the southern Netherlands. In that context, no fewer than eight different sites were drained: Bordeaux and Lesparre in Guyenne, Tonnay-Charente in Saintonge, Sarliève in Auvergne, Capestang in Languedoc, the Marais Vernier in the Seine estuary, and the swamps of Sacy-le-Grand in Picardy.

The organization of the drainage work was continued at the end of the 1630s, even though by then several of the main investors had died. As early as 1640, Johan Hoeufft (1578–1651) and Barthélémy Hervart (1606–1676) began their participation in these projects. Hervart was a German banker from Augsburg,Footnote 25 where his family had been established for a long time, ever since his grandfather had joined Jacob Fugger.Footnote 26 Hervart started his career at the court of Weimar, taking charge of the treasury. During the 1630s, he played the role of go-between with France. Richelieu chose him as middle-man to pay the mercenaries of the Duke of Weimar.Footnote 27 During the 1640s, he served Mazarin with the same loyalty as he had served Richelieu. He was also one of the main partners of Thomas Cantarini, Pierre Serantoni, and Vincent Cenami, who were bankers and associates of Mazarin.Footnote 28 Thanks to his loyalty, Hervart became a key figure in French finances and was made Surintendant des finances in 1655.Footnote 29 He must have met Johan Hoeufft in Weimar, where Hoeufft was also employed by Richelieu to supply the army.

Hoeufft was a merchant from Roermond, or Guelders, in the modern-day Dutch province of Limburg.Footnote 30 After travelling with his family, he moved to France and settled in Rouen (Normandy) in 1600, and received a lettre de naturalité the following year.Footnote 31 Whereas the Comans brothers came to Paris as Catholics, Hoeufft was a Protestant and so was an example of a Protestant migrant from the Low Countries. Hoeufft had experienced a steady rise in international trade ever since his arrival in France. During the first two decades of the century, he developed his business mainly by means of Atlantic trade.Footnote 32 Based in Rouen, he acted as an intermediary between the United Provinces and Spain. After 1609, in a peaceful period, he began to trade directly with Spain. The notaries’ archives of Rouen reveal that Hoeufft was an active shipowner exporting French grains to Italy.Footnote 33 He quickly became used to working with the Dutch East India Company, to which he supplied ships and sold materials to construct them,Footnote 34 and built strong links with Protestant merchants in the Atlantic region.

Until 1630, his main speciality was the trading of metal goods, weapons, and vessels.Footnote 35 Probably, he was close to Van Uffelen, and was thus informed about land reclamation. While continuing his former business, he took great interest in the development of the French financial system. Since 1624 the French monarchy had been fighting the Spanish Crown by financing the troops of Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, among others. Thanks to his family in Amsterdam, Hoeufft was placed in charge of building a link between France and the Weimar court. In compensation for his services, Hoeufft was granted a number of tax farms,Footnote 36 which meant that he could collect different taxes to reimburse his advances to the French monarchy. Hoeufft thus became an agent of Richelieu, who used Hoeufft’s connections in Holland to raise funds on the Dutch money market.Footnote 37 In the next decade, Mazarin employed him in a similar way.Footnote 38 In the first half of the seventeenth century Hoeufft progressively became indispensable to the French monarchy.

In view of the enormous funds involved, it is clear that Hoeufft could not have succeeded alone. He belonged to one of the most powerful bourgeois families of the United Provinces. Hoeufft was a bachelor and had no children, but his nephews followed very successful careers. Two of them require some special attention. Johan Hoeufft junior was canon of the Utrecht diocese, and as a shareholder in the drainage work of Petit Poitou, he took the title of Lord of Fontaine-le-Comte and Choisival.Footnote 39 But that was not his main business, for he was also a director of the Dutch East India Company and closely involved in its overseas trade.Footnote 40 In 1638 he married Isabella Deutz, the daughter of Hans Deutz and Elisabeth Coijmans.Footnote 41 The marriage was the best proof of the perfect integration of the Hoeufft family into the world of international trade. Isabella Deutz was the granddaughter of Balthasar Coijmans, who had built his fortune in international trade and who was, in 1630, the second wealthiest man in Amsterdam.Footnote 42 Furthermore, Isabella’s brother, Johan Deutz (1618–1673), made a brilliant career in Amsterdam, becoming in 1654 the director of trade with the Levant and obtaining in 1659 a monopoly of the mercury trade in northern Europe.Footnote 43

The second nephew of Johan Hoeufft who participated in the construction of his social network was Diderick junior (1610–1688). He spent all his life in Dordrecht and died as Lord of Fontaine-Peureuse, a tribute to his involvement in the draining of the marshes of Sacy-le-Grand, near Compiègne, in Picardy.Footnote 44 Like that of his cousin, the social integration of Diderick can be established from his marriage. In 1641 he married Maria de Witt.Footnote 45 She was Jacob de Witt’s daughter and sister of Johan de Witt, the political leader of the United Provinces from the 1650s until the 1670s.Footnote 46

This then was the history of the drainage entrepreneurs of the Petit Poitou and Arles marshes. Furthermore, Johan Hoeufft participated in an international business network. His family and their business links with the greatest Dutch capitalist families gave him a solid financial base. Several of his relatives and allies were involved in overseas trade, one of the major pillars of Dutch economic growth in the seventeenth century.Footnote 47

The drainage projects undertaken in France between 1599 and the middle of the seventeenth century were based on a collaboration between the French central government and a small group of capitalists and financiers whose main business was based in Amsterdam. Their economic and political powers reinforced each other in a social construction that continued for almost sixty years and resulted in a strong politico-economic network.

Figure 1 Land reclamation in France between 1599 and the 1650s.

The Drainage Works: A Socio-Political Issue

Between 1599 and the 1640s, most of the French drainage projects were undertaken with the help of foreign investors. Thanks to the edicts of 1599 and 1607, they could easily expropriate property from its owners and simply throw out former users of the swamps who did not want to sell their lands or cooperate in the drainage work. Admittedly, they also imported new ways of growing wheat and raising cattle. In that way, the globalization of the economy had consequences on a local scale, even though the drained swamps were very far from the economic core. The cases of Arles and Petit Poitou will clarify the nature of the social disruption caused by the drainage.

The most famous marshes drained in France during the seventeenth century were those of Petit Poitou.Footnote 48 During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Cistercian monks of the area had already conducted an important drainage operation and had constructed the hydraulic infrastructures of the swamps.Footnote 49 Progressively, that equipment fell into disrepair, especially during the Wars of Religion, when Poitou became a region much disputed between Catholics and Protestants.Footnote 50 As a consequence, between the middle of the sixteenth century and the 1640s the swamps were left derelict. The marshes had started to lure investors at the beginning of the 1640s, by which time the drainage programme of Tonnay-Charente, located in Saintonge, a few kilometres to the south of Petit Poitou and near the city of La Rochelle, had begun to prove its profitability (see Figure 2).Footnote 51

Figure 2 The drained swamps of Petit-Poitou. Sources: Cartes IGN au 1/50 000 1327, 1328, 1427 et 1428 and Pierre Siette, Plan et description particulière des marais desseichés du Petit Poitou (1648).

The merit of that work has been attributed to the Dutch for a long time, but the manner of their intervention was unclear. Recently, Yannis Suire tried to show that the draining of Petit Poitou had been the work of local investors only.Footnote 52 It is probable that the local aristocracy did play a key role. In 1641, an entitlement to drain the Petit Poitou swamp was granted to Pierre Siette, an engineer and cartographer to the king, and a representative of the Duke Antoine de Gramont and the Prince de Condé.Footnote 53 Alongside those two investors, it is also useful to mention Julius de Loynes, Richelieu’s personal secretary.Footnote 54 So, to that extent, the reclamation of the Petit Poitou marshland was under aristocratic control, and certainly Richelieu and then Mazarin guided operations.

Nevertheless, the archives, kept in Utrecht, of the Society for the Draining of Petit Poitou show that these local contractors depended on Dutch investors.Footnote 55 Octavio de Strada, who monitored the work for Hoeufft, wrote two notebooks which list the expenditure of Johan Hoeufft in Petit Poitou between 1642 and 1651, the year of his death. During that decade Hoeufft invested 168,135 livres tournois (lt.) in his own name in Petit Poitou. In the meantime, he also lent 622,000 lt. to the main associates in the drainage work, and 200,146 lt. to his own representative in the region, Octavio de Strada.Footnote 56 The Utrecht books show that Johan Hoeufft provided all the money required, enabling the local aristocracy to take control of the region by granting them generous loans and indirectly strengthening support for the monarchy in the region. The land reclamation work therefore affected the agrarian balance and the structure of land ownership.

Almost nothing is known about the exploitation of the Petit Poitou swamps just before their reclamation, and even demographic and economic studies are lacking. Nevertheless, some information can be drawn from de Strada’s notebooks. First, it is important to note that the land reclamation was a very hierarchical enterprise.Footnote 57 De Strada settled two farmers in the polder in order to conduct and survey the work. During the 1640s the work faced no judicial opposition nor were there riots against their installation. On the one hand, such a silence can be explained by political support for the operation, as the main aristocrats of the region were themselves involved in the land reclamation. Furthermore, the monasteries of the area were too weak to take any action.

On the other hand, there were the demographics of the region. Indeed, it is striking that de Strada’s notebooks mention – several times – workers coming from Auvergne or Holland.Footnote 58 That indicates that the drainage entrepreneurs could not find the labour force they needed in Poitou alone and that they had to import them from more remote regions. In other words, the lack of opposition could certainly be explained by the demographic weakness of Poitou and the consequent abandonment of the swamps, which allowed for a reinforcement of the aristocracy’s economic dominance. It is all the more interesting to compare the case of Poitou with the project at Arles in lower Provence, where the demographic trend was the opposite.

In association with Barthélémy Hervart, Johan Hoeufft also superintended important works in the Rhone delta.Footnote 59 Operations began there in 1642, the same year as in Petit Poitou, and the pattern of the enterprise was the same.Footnote 60 Hoeufft did not settle in Provence, so he had to entrust an employee with overseeing the business. He chose Jan van Ens, whose uncle was involved both in land reclamation in Picardy, and in French finances.Footnote 61 Van Ens managed the work from 1642 until his death in 1653. Because of the conflicts he had to face, Octavio de Strada joined him in 1648.Footnote 62

Like the swamps of Petit Poitou, the marshes of Arles had been drained since the Middle Ages,Footnote 63 and their infrastructure too suffered similarly from the social disruption at the end of the sixteenth century, which lasted – in Provence – until 1629.Footnote 64 Despite the similarities, however, the social context in which the work took place was deeply different. First, Hoeufft, Hervart, and their associates did not finance aristocratic support and so intervened in their own names. So, in accordance with the Edict of 1599, after draining the swamp they jointly owned two-thirds of the land as soon as the work was completed, between 1645 and 1646.Footnote 65 As a consequence, they controlled a huge part of the territory of Arles and thus caused a local agrarian revolution by dispossessing members of the local elite.Footnote 66

To carry on this land allocation, all the Arlesian countryside was surveyed in order to ascertain which parcels of land would be given to Van Ens. That work was entrusted to Jean Pellissier, an Arlesian surveyor, and Johan Voortcamp, a Dutch cartographer who had come especially to assist in the drainage work.Footnote 67 Their mission was concluded by the publication of two reports giving the names and titles of all the former landowners of the swamps, including the quantity and quality of the lands they possessed. Thanks to that document, it is still possible to understand how Hoeufft’s investments completely changed the relationship between Arles and its countryside.Footnote 68

First, the two surveyors clearly distinguished two kinds of land. The coustières were the most elevated and the driest lands. Even though they were improved by the work, that part of the country was not involved in the redistribution. The coustières comprised 840 hectares over a total surface of 5,824 hectares. In contrast, the paluds were the lowest and the wettest part of the country. The entire property switch allowed by Van Ens’s work has been calculated for this part of the territory at 4,978 hectares.

The survey reports by Voortcamp and Pellissier allow comparison of the re-apportionment of property before and after the drainage work, and thus enable us to understand the significance of the social consequences of the work. Concerning the situation before the land was drained, two types of information should be taken into account. The surveying of the paluds clearly shows that the area was highly fragmented, since the 4,973 hectares were split into 114 parcels. The division was so thorough that 56 parcels were smaller than 10 hectares. On the other hand, it is relevant to underline that almost half of the paluds were divided into only 9 parcels.

Such an extreme division might explain why the reclamation could have been led only by a foreigner supported by the Crown. Indeed, the ownership of the land surrounding Arles was so split up that it was too difficult to reach any agreeable compromise among the landowners. Furthermore, the survey demonstrates that a large part of the Arlesian population was interested in exploiting the marshes, as 46 per cent of the land and 23 per cent of the parcels belonged to nobles, whereas a large part was in the hands of unidentified individuals – probably commoners of some sort (see Tables 1 and 2). Thus the Arlesian aristocracy was by far the strongest landowner in the marshes.

Table 1 Property distribution before drainage work carried out by Van Ens (1645–1646)

Key: A < 5 hectares; 5 ≤ B < 10 hectares; 10 ≤ C < 20 hectares; 20 ≤ D < 50 hectares; 50 ≤ E < 100 hectares; 100 ≤ F < 300 hectares; 300 ≤ G < 500 hectares; 500 hectares ≤ H.

Source: “Rapports de désemparation des terreins desséchés pour prix du contrat du 16 juillet 1642, des 14 août 1645 et 30 avril 1646”, DAD, pp. 62–88.

Table 2 Property distribution after drainage work carried out by Van Ens (1645–1646)

Key: A = 5 hectares; 5 ≤ B < 10 hectares; 10 ≤ C < 20 hectares; 20 ≤ D < 50 hectares; 50 ≤ E < 100 hectares; 100 ≤ F < 300 hectares; 300 ≤ G < 500 hectares; 500 hectares ≤ H.

Source: Table 1.

In accordance with the Edict of 1599, two-thirds of the total land reclaimed was given to Van Ens; he therefore took possession of 3,316 hectares of land. The reclamation thus caused a huge change in the character of land ownership, involving all groups and classes. Nevertheless, the small landowners may have been the main victims of his work since their parts of the marshes were reduced to tiny parcels.

Van Ens could thus dominate the entire Arlesian countryside. He took his two-thirds share in each parcel, so that his property was divided into 114 different parts. This seemed to be a weakness at first sight, but it actually reinforced his work, none of the landowners being effective enough to propose alternative ways of managing the water. So, four years after his arrival in Provence, Hoeufft and his associates became the most important landowners in the Arlesian area and transformed the traditional partition of landed property.

The new ownership of the territory drastically changed the social balance of the town.Footnote 69 On the one hand, supporters of the growth of royal power in Provence backed the operations, while adherents of the parliament of Provence, an institution that had traditionally rallied opposition to the king, launched a long-lasting struggle against the drainage entrepreneurs.Footnote 70 Attitudes to land reclamation were therefore determined by political divisions.Footnote 71 The main social consequences of the draining operations were connected to the political evolution of Provence.

The opposition to Van Ens’s work strengthened ancient divisions. The struggle between the two parties took two different forms. First Hoeufft’s enterprise was undermined by riots and the destruction of the new infrastructure. Arlesian archives provide proof of outbreaks of violence, which also involved inhabitants of the nearby town of Tarascon (see Figure 3 overleaf). Located a few kilometres to the north of Arles, Tarascon could only release its flood waters onto Arles’s territory. If the water flow were to be stopped, Tarascon’s countryside would be condemned to remain under water. That is the reason why Arles’s neighbours were so angry when, in 1647, a boat was sunk in a freshly dredged canal in order to make it flood into some recently seeded land owned by Van Ens and destroy the future harvest.Footnote 72 His opponents thus forced Van Ens to choose between his lands and those of Tarascon’s inhabitants, and in the end the Tarascon mobilization compelled Van Ens to flood his own lands.

Figure 3 Tarascon’s plain, the north of Arles territory and the Baux Valley. Source: Carte IGN TOP 100 066.

For its part, the chapter of Saint-Trophime, in the episcopal see of Arles, chose a different way to undermine Van Ens. The draining of a large part of the Arles territories had actually involved a population move. The peasants of the Crau, a dry and infertile region located in the south-east of Arles’s territory, came to settle in the new land. This shift had a heavy impact on the chapter’s budget, which suddenly lost the revenues of the tithe usually paid by the peasants. Indeed, the drained lands were exempted from this clerical tax during the first twenty years of their exploitation.Footnote 73 In response to the change involved in land reclamation, the chapter launched legal proceedings to restore its right to the tithe on the new land.Footnote 74 After being heard in an ecclesiastical court, the dispute was finally settled by the Intendant of Provence, the representative of the king in the region, who imposed a compromise between the contractors and the chapter, and obliged Van Ens to pay a part of the tithe.Footnote 75

To overcome those two kinds of opposition, the entrepreneurs had to seek the permanent backing of the central government, and without the intervention of the Queen Regent and her prime minister, Mazarin, they would not have been able to defeat their opponents.Footnote 76 It is thus all the more significant to note that Hoeufft and his associates succeeded. Despite the difficulties, he managed to make a lot of money from his exploitation of the new land. In fact, the major social consequence of the land reclamation concerned the social structure of the city of Arles.

Intrinsically bound to the growth of centralized power, the success of the drainage work went hand in hand with the marginalization of the supporters of the Provencal parliament’s authority. In short, Hoeufft’s investment was used by the monarchy as a means to transform the social structure of Arles. From that point of view, the cases of Petit Poitou and Arles are very different. Indeed, in Poitou the monarchy’s authority faced no opposition. Another difference lay in the impact on the local populations.

From north to south, the economic trend of the seventeenth century in France was very different. Since the work of René Baehrel, it has been firmly established that southern France was marked by both economic and demographic growth, while the situation of northern France was less favourable.Footnote 77 Before its draining in the 1640s, Arles’s swamps were used intensively, as is revealed in the several trials launched against the entrepreneurs. A summons addressed to Van Ens by Antoine Garnon, an Arlesian fisherman, revealed that the Dutch engineer had filled in his canal in order to modify the hydraulic network.Footnote 78 Thus, the land reclamation deprived this fisherman of his main source of revenue.

The initial contract signed in 1642 gave Van Ens ownership of the whole hydraulic structure so that he could take possession of all the fisheries settled in the swamps, including the ownership of the new levées and plantings. Thanks to those rights he was able to exploit the trees and mustard that grew on the dykes. Indeed, mustard plants contributed to consolidate the dykes and offered a convenient income to the landowner. In 1647 Truchenu, an Arlesian noble who had been accustomed to exploit it before Van Ens’s work, launched an action against him because Van Ens had confiscated the mustard harvest.Footnote 79 As the new owner of the whole hydraulic network, Van Ens also collected taxes on the navigation on his canals. The quarries of Fontvieille, which used to sell their stones in Arles, were thus among the firm opponents of the drainage work.Footnote 80 These examples illustrate the fact that the land reclamation had a deep impact in all layers of Arlesian society.

Thus, both Petit Poitou and Arles demonstrate its strong societal impact. In Poitou, as in Provence, the drainage work was used to strengthen the power of the French monarchy and the local implantation of its loyal aristocracy. The Crown employed the funds, the skills, and the commercial networks of the Dutch traders to extend its power throughout the whole kingdom, while its aristocracy used them to exploit their wetlands. At the same time, land reclamation was linked to the dispossession of the local peasantry. And, as we shall see, the policy also had a deep impact on the environment of the wetlands.

Environmental Consequences Of Land Reclamation In Arles And Petit Poitou

To measure the environmental impact of the work undertaken in the seventeenth century, historians need a long-term analysis. The modern draining of Arles and Petit Poitou affected areas equipped and exploited since the Middle Ages and gave them the shape they have today. In both regions, capitalist operations led by Johan Hoeufft caused lasting environmental changes. Nevertheless, those changes progressed differently in Poitou and Provence.

The swamp of Petit Poitou is located in the bay of the Aiguillon and is the result of tidal sediment.Footnote 81 Despite its geological origins it had not been subject to flooding from the sea for a long time, but it was regularly flooded by the waters of the Lay and Vendée, coastal rivers flowing into the Aiguillon bay. The main purpose of the drainage projects was therefore to divert that water into the sea as quickly as possible. The modern entrepreneur was helped by the intensive work completed in the area by Cistercian monks, who had already begun to drain the area during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.Footnote 82

When he arrived in Poitou to manage the land reclamation, de Strada found former canals still visible in the landscape, even though they were filled in with sediment. The task then was to renew the old infrastructure. He dredged the pre-existing canals and built new sluices, using local and foreign labour to do so. Thus, de Strada used workers from Auvergne, where he had settled, and imported Dutch cows and materials, including timber and bricks from Amsterdam and Hamburg.Footnote 83 Within a few years, he had succeeded in converting an unexploited swamp into arable and grazing land from which grain was exported to Amsterdam.Footnote 84

The draining of the Petit Poitou swamp provided Hoeufft and his associates with a good return on their investment, thanks to the sale of grain and interest paid by associates. Nevertheless, the operation was not solely a short-term business. Indeed, at the beginning of the 1670s Johan Hoeufft’s heirs still owned several farms in Petit Poitou. A notebook written between late 1670 and early 1671 shows that more than 20 years after the work had been completed Petit Poitou still provided an annual income of more than 7,264 lt.Footnote 85 Two-thirds of that income was derived from oats and one-third from the sale of horses and cows. In return, the owners had to invest 370 lt. a year for the maintenance of the polder, to clear the canals, and to maintain the buildings of the area.

So, in a normal year, the land of Petit Poitou could offer landowners an income of almost 7,000 lt. Later, during the eighteenth century, Hoeufft’s heirs still possessed their farms in Petit Poitou and chose to sell them at a good profit.Footnote 86 Between 1734 and 1741 the 23 farms owned by Hoeufft’s heirs were sold and the proceeds of 254,000 lt. were divided among the different branches of the family. This amount clearly shows that the lands drained in the middle of the seventeenth century were still valuable in the following century, indicating that they had been steadily maintained and could still provide good revenues. The drainage works undertaken by Hoeufft and his associates are, even today, characteristic features of the area: all the farms built by Hoeufft still exist, and the toponymy has remained the same (see Figure 1).Footnote 87 Moreover, the draining of Petit Poitou prompted a sort of drainage fever, with projects multiplying in nearby regions.Footnote 88 Entrepreneurs increasingly turned their attention to the sea, launching a continuous wave of land reclamation that completely altered the environment of Aiguillon’s cove within 200 years.

Figure 4 Farms of Choisival in the Petit Poitou’s swamps. The two barns on the right were built in the 1640s, though they have been restored. The main part of the farms built by Hoeufft has similar barns. Photograph by the author.

That evolution must be compared with the case of Arles. Settled by the Romans in the first century CE, the city of Arles always had to deal with water problems.Footnote 89 It was actually impossible to develop agriculture without draining the territory and protecting it from the Rhone flood. Medieval Arlesians built contrivances specifically to achieve that aim, but by the beginning of the seventeenth century the mechanisms had become inadequate.Footnote 90 At that time, they had to face the little Ice Age too and the consequences of social disruption caused by the Wars of Religion.Footnote 91

As in Petit Poitou, Hoeufft and his associates dealt with a damaged, but previously developed countryside. Despite the need for new land, Arlesians had neither been able to build a consensus to drain their area, nor to negotiate with other towns of the region to regulate floodwater. Against that background, the mission of Van Ens appears in a different light. He had to change the way the water was managed and renew the old infrastructures. That became feasible as he concentrated all the canals and two-thirds of the land into his own hands.Footnote 92 By becoming the most important landowner in the region, he could easily lead the restoration of the former drainage system, and then complete it by digging new canals. Along with his restoration work, Van Ens also constructed a complex system to separate waters according to their origins.Footnote 93 Thanks to this system, water from the Baux valley was separated from that coming from Tarascon, and its management was simplified.

As in Poitou, Hoeufft’s enterprise led to a crucial environmental change in the Arlesian countryside which still strongly marks the area. Whereas the draining of Petit Poitou was small-scale compared to all the regional wetlands, the work of Van Ens directly involved the whole left bank of the Rhone from the northern limit of Arles’s territory to the Mediterranean Sea (an area of 110 square kilometres). The land reclamation of the 1640s covered all the arable land in the area.

Despite some floods, notably in the 1670s, Van Ens’s constructions seem to have remained effective until the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 94 In 1706, a catastrophic flood severely damaged the area, but in 1707 an agreement between Arles and Tarascon allowed for repairs.Footnote 95 A few years later, in 1718, Maître Pierre Lenice, the director of the polder, a lawyer and member of the Paris parliament, and representative of Hoeufft’s heirs, was forced to pay his share of the maintenance charges. The sum of 75,809 lt. had to be paid to the corps des vidanges,Footnote 96 money which was spent on necessary work to keep the swamps of Arles drained.Footnote 97 In 1734 and 1736, two rulings obliged entrepreneurs to dredge canals and renew bridges built within the land drained.Footnote 98 Again, Hoeufft’s family interests were defended by Maître Pierre Lenice, representative of Hoeufft’s heirs, and also by François Devese, Seigneur de Lalo des Pluches, who, as one of Hoeufft’s heirs, took a personal interest in the land reclamation.Footnote 99

It seems that reclamation in the Arles region suffered at the end of the eighteenth century, although as soon as the French Revolution began several projects sprang up to continue the work of Van Ens. In 1791, 1795, and in 1802, Arlesian citizens gathered to talk about the need to drain the marshes again.Footnote 100 They finally received the support of the French government, which agreed to supervise the work in 1807.Footnote 101 The work was then led by an engineer who continued to work in the vein of Van Ens’s projects.Footnote 102 For example, the engineers of the Ponts et Chaussées used the network and installations that had been renewed two centuries earlier. Their task was eased by the regular upkeep of the Van Ens installations, which remain the basic framework of modern water management in the low Rhone area.

In short, from technical and environmental viewpoints, both the Arles and Petit Poitou land reclamations were very similar. On the one hand, they both enjoyed a medieval inheritance of former drainage works so that the entrepreneurs could build upon former infrastructures, and each used similar means to reach their ends. Furthermore, the environmental impact of both projects was far-reaching. The infrastructure is still quite effective even today.

Conclusion

Focusing on the two cases of Petit Poitou and Arles, I have argued that the whole process of land reclamation undertaken in France between 1599 and the 1650s relied on the involvement of foreign agents, who were employed by the French aristocracy. Most of the foreign agents came from the southern Low Countries and had established their business in Holland. The drainage works of seventeenth-century France benefited from the Dutch Revolt and the beginning of the Eighty Years’ War. The role of the Comans brothers, Van Uffelen, and Hoeufft was decisive in the success of Henri IV’s policy. They were allowed to invest directly in the land drained and to lend money to other investors. In fact they were used as agents of French royal power. For instance, Hoeufft provided Mazarin with people who were able to manage large drainage projects and market the produce of the new land created. In relation to their commercial connections in Amsterdam, Hoeufft, like Van Uffelen before him, relied on a strong business network.

That organization was the reason why the French monarchy gave its crucial backing to land reclamation. Senior French state officials were directly interested in the successful outcome of the drainage work. As a consequence of their interest, they used their official positions to suppress legal disputes that could have endangered it. Conversely, the drainage entrepreneurs helped the Crown, and the prime minister, to affirm their authority in the areas concerned. The draining of the Arlesian marshes thus accompanied the growth of royal power in Provence. The French monarchy used the economic power of Amsterdam to strengthen its own power over its provinces, while Dutch capitalists benefited financially from the adventure.

Such collusion between the economic and political powers upset the social balance built by the communities surrounding the different wetlands. Indeed, the draining of the marshes meant appropriation of land by the investors and thus expulsion of former users. In Arles, some fisheries were destroyed, while Hoeufft and his associates took possession of others. Moreover, land drainage involved different kinds of migration. In Arles, Van Ens had to ease the movements of peasants coming from the Crau, which was a small-scale migration. But in Petit Poitou the drainage work was made possible thanks to workers coming from the Auvergne. To sum up, the draining of the French wetlands weakened the local population by curtailing their rights whereas it reinforced the local bourgeoisie and aristocracy, who accepted the growth of royal power.

In that sense, it is interesting to consider the social conditions of their success. In both cases, Hoeufft built hierarchical companies which dealt with the territory as a whole. Van Ens succeeded because he was the sole owner of the canals and because he possessed two-thirds of the area. De Strada and Hoeufft employed exactly the same method in Petit Poitou. The similarity between the statutes of the Arles swamp and those of Petit Poitou supports these findings.Footnote 103 The social changes were all the more striking as they left deep marks on the environment. The infrastructure they built, or rebuilt, is still in use today. More than technical skills, the Dutch imported a certain way of exploiting the swamps, which remained undisputed until the end of the twentieth century, when the rise of a new “green consciousness” started to question their achievements again.