Diet and fitness apps often are touted as a means to improve users’ health. Most of these apps consist of nutrition, food, physical activity, weight and even sometimes body measurement tracking tools and connections to a community of users with similar goals. Although these apps are popularReference Fox and Duggan1,Reference Krebs and Duncan2 and can be helpful to some,Reference Schoeppe, Alley, Van Lippevelde, Bray, Williams and Duncan3 they can have unintended adverse effects on others, such as university and college students.Reference Simpson and Mazzeo4–Reference Eikey and Reddy7 These apps often overwhelmingly focus on weight loss and normalise weight control methods. Using weight loss as a proxy for health is problematic because it may increase the risk of or exacerbate eating disorder behaviours in already susceptible groups, such as women attending university.Reference Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder and Kirz8 Further, these apps tend to overlook the role of mental health in addressing physical health challenges. The emphasis on weight loss within these apps is consistent with and feeds into Western cultures’ obsession with thinness and dieting. Diet and fitness apps also support and encourage dieting behaviours. This is an issue because dieting behaviours and unhealthy weight control methods are also risk factors for eating disorders.Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Guo, Story, Haines and Eisenberg9,Reference Ackard, Croll and Kearney-Cooke10 Additionally, when compared with, for instance, paper tracking, these apps are always on hand and more discreet because of the prevalence of and norms around smartphone use, making it easier to constantly engage with diet and fitness content. They also often provide users with a set plan based on how much weight they want to lose, and leverage features, such as progress visualisations to influence behaviour, colour choices to denote positive and negative behaviours, and reminders and streaks to encourage consistent tracking. Although disordered eating affects all genders, eating disorders and eating disorder-related behaviours are extremely prevalent among women, especially those in college and university settings.Reference Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder and Kirz8,Reference Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner11–Reference Berg, Frazier and Sherr13 In fact, researchers have found that 13.5% of undergraduate women screen positive for eating disorders,Reference Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder and Kirz8 and 40–49% of university women engage in eating disorder behaviours at least once a week.Reference Berg, Frazier and Sherr13

Only somewhat recently have researchers studied diet and fitness apps in the context of eating disorders.Reference Simpson and Mazzeo4–Reference Honary, Bell, Clinch, Wild and McNaney6 For example, Honary et alReference Honary, Bell, Clinch, Wild and McNaney6 found that almost half of the young people who participated in their study had maladaptive eating and exercise behaviours from using diet and fitness apps. In their study of 493 college students, Simpson and MazzeoReference Simpson and Mazzeo4 found that those who reported using diet and fitness apps had higher levels of eating disorder symptoms. Similarly, but focusing on individuals with clinically diagnosed eating disorders, Levinson et alReference Levinson, Fewell and Brosof5 found that in their cohort, 73% of those who used MyFitnessPal perceived it as contributing to their eating disorder, and these perceptions were correlated with eating disorder symptoms. Although these studies are important to recognise the link between eating disorders and diet and fitness apps, they do not shed light on how these apps may unintentionally affect users and their eating disorder symptoms. To address this gap, a qualitative study was conducted to answer the following research question: what are the unintended negative consequences of diet and fitness apps among women attending university who exhibit eating disorder-related behaviours? The term ‘unintended consequences’ refers to unforeseen or unpredicted results.Reference Fayet, Petocz and Samman42 This terminology is common when discussing technological impact, especially related to health information technology. These consequences can be positive, negative or neutral, but often refer to adverse effects.

The research question

This study takes an interpretivist perspective: knowledge is contextual and grounded in participants experiences.Reference Hiller, Wheeler and Murphy15 This paper reports on one portion of a study on the use, impact and perceptions of diet and fitness apps (and if they are used in conjunction with other technologies, such as social media). Eight themes emerged that highlight the unintended negative consequences of diet and fitness apps. Findings from this study can be used by app designers, educators and clinicians to more carefully consider how these apps affect users, especially young women to whom these apps are often marketed.

Eating disorder behaviours

For the purposes of this research, eating disorder behaviours are behaviours associated with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. These include excessive calorie or food restriction; intense fear of gaining weight; obsession with weight and consistent behaviour to prevent weight gain; self-esteem overly related to body image; bingeing; feeling of being out of control during bingeing; purging; dramatic weight loss; preoccupation with weight, food, calories, fat grams and dieting; refusal to eat certain foods; comments about feeling ‘fat’; hunger denial; excessive exercise regimen and development of food rituals.16 Because many women do not see a professional for their symptoms and thus never receive a diagnosis,Reference Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder and Kirz8 eating disorder behaviours in this context may or may not indicate full clinical eating disorders or qualify to be categorised as other eating disorders, such as other specified feeding and eating disorder or unspecified feeding and eating disorder. The women in this study self-identify as having an eating disorder. Therefore, in the remainder of this paper, eating disorder behaviours and eating disorders are used interchangeably to emphasise women's own perspectives and experiences with eating disorders, and the importance of studying eating disorders even in the absence of a clinical diagnosis.

Method

To capture rich information from individuals about how diet and fitness apps may affect eating disorder-related behaviours and perceptions, a primarily qualitative research approach was employed. This methodology allowed for users to share their stories and experiences in their own words and emergent themes unlikely to be discovered when using only quantitative approaches. Three data collection methods were used: surveys (demographic and eating disorder symptoms survey), think-aloud exercises and semi-structured interviews.

Recruitment

In total, 24 participants took part in the study. The focus of this research was university women with eating disorders who use or have used diet and fitness apps in the USA. Participants who were either formally or self-diagnosed were recruited. This was specifically done to include the portion of women who do not seek a professional diagnosis or treatment. Therefore, this study represents users whose needs are largely invisible. This population is important to study because anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorder behaviours tend to affect university women,Reference Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder and Kirz8 and diet and fitness app users tend to be younger.Reference Fox and Duggan1 To recruit users, on-campus groups were asked to share information on a campus listserv and fliers were posted to social media. Additionally, paper fliers were posted on bulletin boards on and off campus, such as at local gas stations. Because eating disorders are stigmatised conditions, many people may be wary of being seen getting contact information from fliers. Posting paper fliers in discreet locations, such as on the backs of doors in public restroom stalls where participants could covertly obtain information for the study, was the most successful approach.

Measures

Demographic and eating disorder symptoms survey

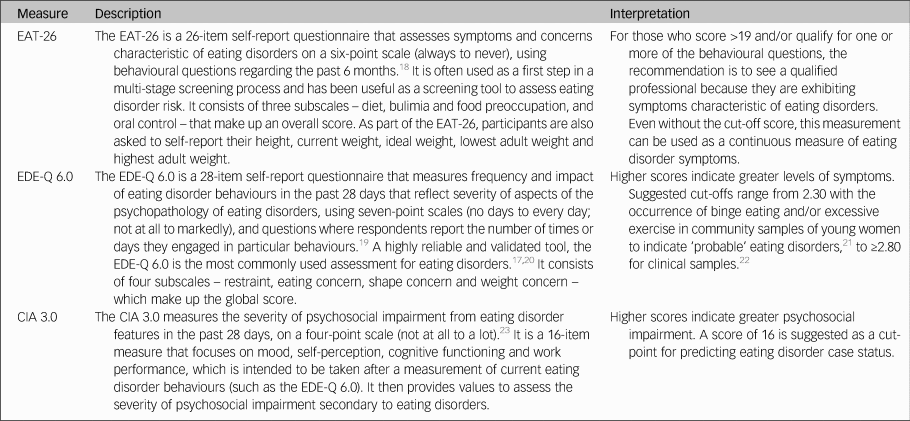

The survey contained questions about age, gender, and race/ethnicity, as well as eating disorders and app use. A combination of three well-known measures for assessing the severity of disordered eating and exercise behaviours and attitudes was used, which is similar to Tan et alReference Tan, Kuek, Goh, Lee and Kwok17 and described in Table 1: the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26),Reference Garner, Olmsted, Bohr and Garfinkel18 the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0)Reference Fairburn and Beglin19 and the Clinical Impairment Assessment Questionnaire (CIA 3.0).Reference Bohn, Fairburn and Fairburn23

Table 1 Description of eating disorder symptoms measures

EAT-26, Eating Attitudes Test; EDE-Q 6.0, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; CIA 3.0, Clinical Impairment Assessment Questionnaire.

Think-aloud exercise

The think-aloud is a method in which participants speak out loud thoughts that come to mind as they go through a task.Reference Charters24 The objective with the think-aloud exercise was to explore participants’ perceptions linked to specific aspects of the app. Participants went through three tasks: setting goals, viewing progress visualisations and using social and community features of the app. As users went through these tasks, they were asked to speak aloud what they were thinking and feeling as they interacted with the app.

Semi-structured interview

The purpose of the interviews was to understand participants’ general experience with and perceptions of diet and fitness apps. Participants answered questions regarding why they used diet and fitness apps, the role the app played in their eating disorder behaviours (both positive and negative), unanticipated effects and their reflection on their use over time. At approximately 14 interviews, repetitive themes in the participant responses were apparent and converged into the same points (i.e. data saturation).

Procedure

Although there were distinct methods of data collection, they occurred during the same session. All sessions began with the demographic and eating disorder symptoms survey. All participants took the demographic survey; five opted not to take the eating disorder symptom survey. Current app users (n = 17) then participated in the think-aloud followed by the interview. Former app users (n = 7), on the other hand, only participated in the interview after taking the survey. In those cases, participants discussed how they used the app and were asked to recall specific features. Participants were compensated $25 each for approximately 1 h of their time. All but one data collection session took place in person (one was conducted via telephone).

Ethics

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees (Institutional Review Board approval number: STUDY00004634) on working with human participants. Institutional review board approval was obtained from Pennsylvania State University, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Materials were reviewed by a mental health professional. Resources were provided to every participant. Participants who currently did not use diet and fitness apps were not asked to interact with apps to avoid potential triggers. A plan was in place to work with participants in seeking support should they need it during or after a session; participants were reminded they could cease the session at any point. Because participants were students at one university, the university's Center for Counseling and Psychological Services was available to participants.

Data analysis

Excel for MacOS and JASP for MacOS (JASP Team, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands; see https://jasp-stats.org/) were used to organise and analyse the quantitative data from the demographic survey and eating disorder symptoms measures. Body mass index (BMI) was derived from height and weight data. For those aged ≥20 years, BMI was computed with the United States National Institute of Health calculator (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm), and for those aged <20 years, BMI was calculated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculator (https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpabmi/calculator.aspx). Think-aloud exercises were video and audio recorded, and interviews were audio recorded. In total, the think-aloud exercises and semi-structured interviews were 21 h and 36 min. The think-aloud exercises and interviews were transcribed for a total of 436 pages, and analysed together. The data were analysed by the author, using Braun and Clark's thematic analysis approach,Reference Braun and Clarke25 which included becoming familiar with the data, systematically identifying codes and themes, and defining and naming the common themes found across the entire data-set. Similar discussions and answers were grouped together, and initial codes related to unintended negative consequences were developed. During data collection, the analysis was iteratively performed to refine the themes as more data was collected. The videos and still images were used to better understand specific app content and features to which participants were referring.

Results

Participant demographics

Participants were aged 18–23 years, with a mean of 20.63 years. The majority of participants identified as White (non-Hispanic) (n = 18), with one from Israel; three identified as Asian, Asian American or Pacific Islander; two identified as multi-racial and one identified as Native American or American Indian. Most participants had not been professionally diagnosed with an eating disorder (n = 17), and most reported being in recovery or recovered (n = 20). Participants estimated they had an eating disorder anywhere from 2 months to 7 years (mean 34.93 months, s.d. 26.78 months), and most (n = 20) felt that their eating disorder began before using diet and fitness apps. The most used app was MyFitnessPal (n = 21); however, many of the other apps used had similar features to MyFitnessPal. Participants reported using diet and fitness apps anywhere from 2 months to 8 years (mean 30.21 months, s.d. 30.05).

Participants reported current (mean 22.90, s.d. 3.58), high (mean 24.71, s.d. 3.84), low (mean 19.54, s.d. 3.40) and ideal BMI (mean 21.13, s.d. 2.26). At the time of data collection, most participants were in the healthy range (n = 16), followed by overweight (n = 2) and obese (n = 1). Highest reported BMI for participants was most often in the healthy range (n = 14), followed by overweight (n = 3) and obese (n = 1). Lowest reported BMI most often fell in the underweight (n = 8) or healthy range (n = 8), followed by overweight (n = 2). Most participants reported an ideal weight in the healthy range (n = 17), followed by underweight (n = 1) and overweight (n = 1). Seventeen out of nineteen participants reported their ideal weight as less than their current weight, and only two reported their ideal weight as higher or the same as their current weight.

Sixteen out of nineteen participants answered one or more of the eating disorder questionnaires in a way that suggested eating disorder symptoms. For the EAT-26, the overall mean score was 21.32 (s.d. 10.63), and 15 out of 19 participants exceeded the cut-off point. For the CIA 3.0, the overall mean of all 19 participants did not reach the cut-off point of 16 (mean 14.84, s.d. 10.39); however, nine participants exceeded this threshold. For the EDE-Q 6.0 global score, the overall mean of 2.70 (s.d. 1.04) was between suggested cut-off points.Reference Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen and Beumont21,Reference Mond, Myers, Crosby, Hay, Rodgers and Morgan22 Scores were also compared with the norms of university women, which was computed by taking the norm mean (1.65) and adding 1 s.d. (1.30), to equal 2.95;Reference Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner26 ten participants exceeded this threshold. Additional information can be found in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1011.

Themes

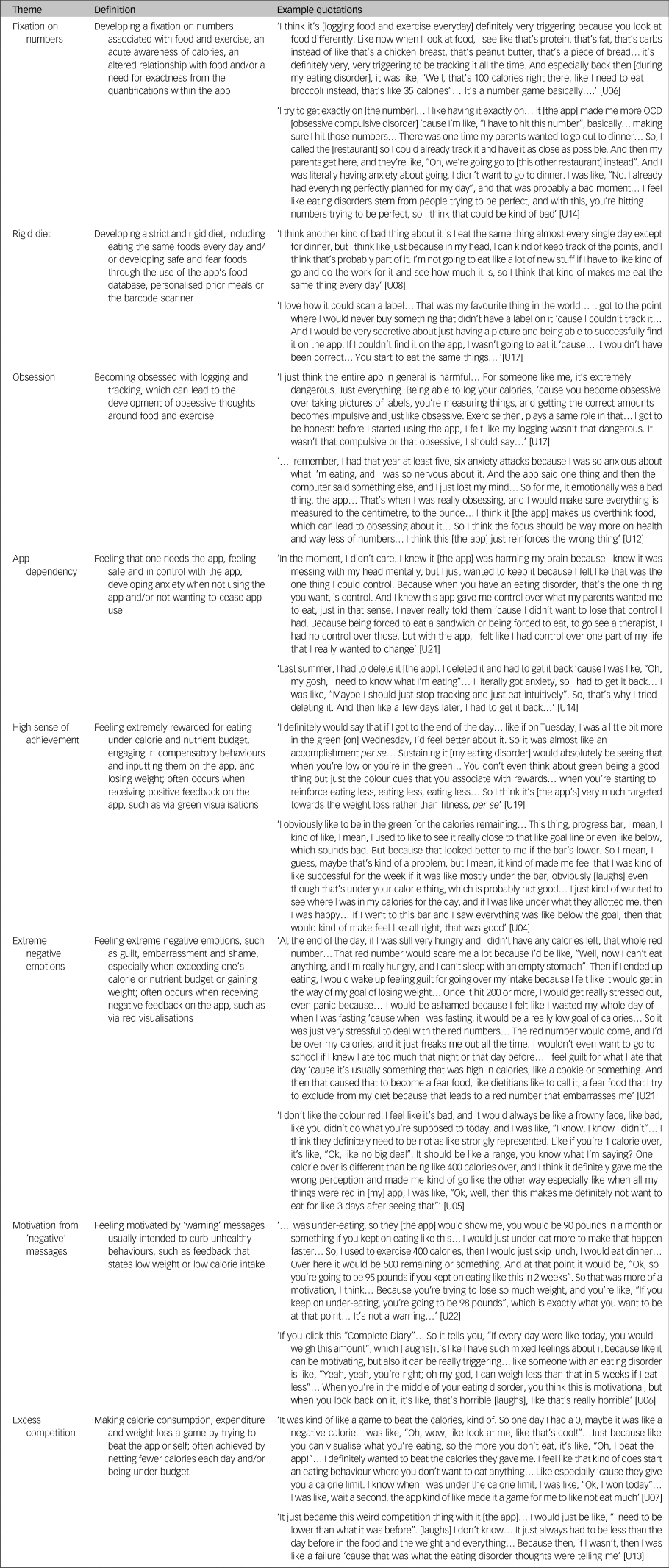

Eight types of unintended negative consequences from using diet and fitness apps emerged, which can be seen in Table 2. These themes focus on the interaction between the user, context and app, and how the design of apps affects attitudes and behaviours. These themes include fixation on numbers, rigid diet, obsession, app dependency, high sense of achievement, extreme negative emotions, motivation from ‘negative’ messages, and excess competition. Although these were common when users’ focus was to lose weight or eat less, these adverse effects were also prevalent when users wanted to gain weight, eat more or focus explicitly on eating disorder recovery. As a result of these unintended negative consequences, some participants reported secondary effects, such as interference with personal relationships, social outings, school and work, as well as increased health issues.

Table 2 Emergent themes, definitions and example quotations

Participants discussed developing a fixation on numbers, fuelled heavily by the app's quantification, which worsened their eating disorder behaviours and changed their relationship with food. Having used the apps so much, many participants reported already knowing the calorie content of every food they ate before logging it. Participants also explained that they tended to eat the same foods each day because they knew the calorie content and could mitigate any unknowns about what they were consuming (even if they abandoned the app). The app also fed into the concept of fear foods and safe foods, where users would only buy and track foods if they were aware of their calorie content (e.g. in their personal app database or foods that had a barcode).

They described becoming obsessed with logging their food intake, and developing obsessive thoughts around food and exercise that sometimes interfered with schoolwork. For example, some participants used the app to log all their meals in advance, which acted to strictly control their consumption. Some also described developing a dependency on these apps. Many participants discussed how they needed the app and became very anxious when they stopped using it; they sometimes redownloaded the app to relieve their anxiety. One participant described how uncomfortable she was when she went to a clinician who wanted her to explore the idea of not using her physical activity tracker (Fitbit).

A number of participants described the role of green progress visualisations, which users see when they have remaining calories on MyFitnessPal and similar apps. Many expressed feeling rewarded when viewing this feedback, as it signalled they were consuming less than their allotted calories. On the other hand, participants felt guilt, embarrassment and shame over exceeding their calorie budget and being shown red visualisations in response. The extent to which they exceeded their budget affected participants differently. Some expressed that they felt badly regardless of how much they went over their budget, whereas others explained how they felt worse the higher their calorie number exceeded their budget. Many participants also described being in an unhealthy competition with themselves and with the app to eat less and less each day, because the app ‘gamified’ eating, exercise and tracking.

Although there are some features in diet and fitness apps that attempt to curb maladaptive eating and exercise behaviours, participants explained that these did not work as intended. For example, MyFitnessPal has a feature called ‘Complete Diary,’ which is a button that allows users to tell the app they are finished logging food, exercise and weight for the day. Once clicked, either a warning message or weight projection appears. Many participants found both types of messages to be motivating to continue to lose weight regardless of the content or context of the message.

Discussion

Unintended negative consequences are prominent regardless of where users are in their journey (e.g. recovery or not). This is a result of the design of diet and fitness apps, the individual and their context. This section first discusses implications for educators and clinicians, and then critically examines the design of diet and fitness apps and offers suggestions for improvement.

Implications for clinicians and educators

Understanding the unintended consequences can be useful for psychiatrists, psychologists and other mental health experts, as well as general practice clinicians, to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders. Especially in college and university settings, healthcare professionals should be aware of and engage in discussions about the use and potential downsides of diet and fitness apps. Educators should also be privy to possible unintended negative effects to prevent triggering or exacerbating maladaptive eating and exercise behaviours. By encouraging or even requiring the use of digital food and physical activity tracking as part of nutrition courses and ‘healthy’ university initiatives (e.g. https://www.usatoday.com/story/college/2016/01/19/oklahoma-college-tracks-students-fitness-with-fitbits/37410983/), educators may unknowingly exacerbate eating disorder-related issues, especially among university women. Therefore, great caution should be exercised when considering promoting diet and fitness apps, especially in these settings. As always, it is important to remember that app users and app use exist in a larger context, where societal norms and external pressures influence the effects of these tools.

Rethinking diet and fitness app design

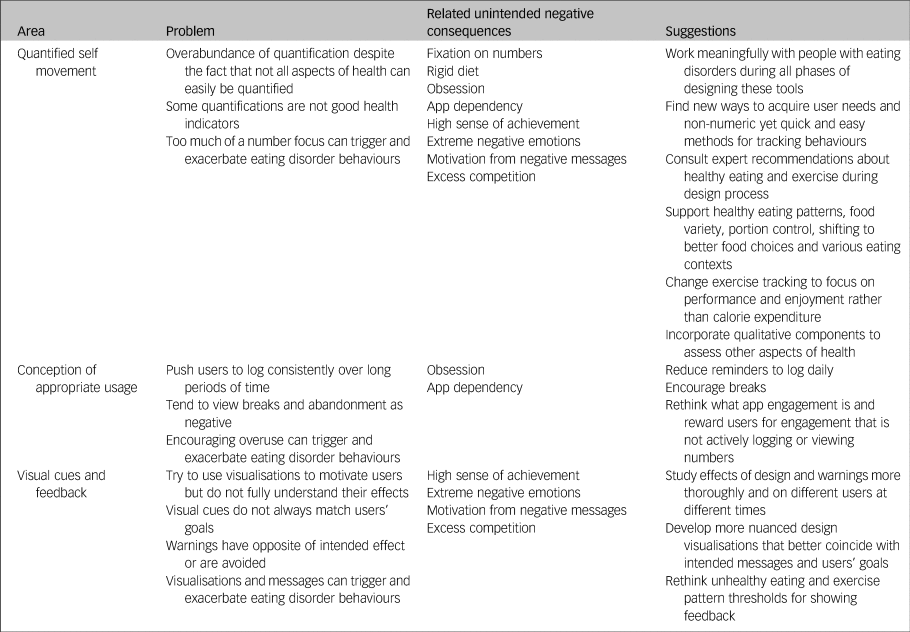

The design of diet and fitness apps may partially contribute to unintended negative consequences, which are related to three major areas: the quantified self movement, our conception of appropriate usage, and visual cues and feedback. Table 3 outlines how these findings relate to app design, to help us understand where we can make improvements to minimise unintended negative consequences and focus more on promoting healthy behaviours. However, it is important to note that although small changes may have some positive impact, this work highlights the need to change how we think about health promotion in digital tools by focusing on the mental health needs of users and the interplay between mental and physical health. A more holistic and personalised approach is consistent with prior literature on supporting the needs of people with eating disorders.Reference Mitrofan, Petkova, Janssens, Kelly, Edwards and Nicholls27

Table 3 Summary of suggestions to address diet and fitness app issues

Quantified self movement: moving beyond numbers

The quantified self is reflected in diet and fitness apps’ heavy focus on numbers. Although self-tracking numeric data has benefits,Reference Choe, Lee, Lee, Pratt and Kientz28–Reference de Vries, Kooiman, van Ittersum, van Brussel and de Groot30 findings cast light on issues with the quantification and tracking of behaviours related to diet and exercise, especially for those with a history of eating disorders, which has been supported by other literature.Reference Honary, Bell, Clinch, Wild and McNaney6,Reference Lupton31 Users with eating disorder behaviours develop a fixation on numbers and a rigid diet partly because of diet and fitness apps’ heavy focus on numbers, as well as features such as barcode scanners, which are aimed at reducing user burden but actually encourage eating pre-packaged and fast foods,Reference Cordeiro, Epstein, Thomaz, Bales, Jagannathan and Abowd32 which often are not the healthiest options. Because food, exercise and weight are quantified and goals are numerically driven, users become overly preoccupied with numbers, and food begins to be viewed as its caloric and macronutrient content.

Although the quantified self movement has its merits, it is clear that using numbers as indicators of health has its limitations and feeds into the need for control, which is a hallmark of eating disorders. To begin to reduce unintended negative consequences, designers, developers and researchers need to focus less attention on quantifying food, weight and exercise. Instead, understanding what a healthy lifestyle is and finding ways to promote that with technology is imperative. For example, rather than focus mostly on calories, apps should be designed to help users develop a positive relationship with food and their body, as well as healthy eating patterns that include fruits, vegetables, protein, dairy, grains and oils; focus on food variety, nutrient density and amount/portion sizes; help limit added sugars and saturated fats, and reduce sodium intake; find ways to help people shift to healthier options and assist healthy eating in various settings (home, work, school, restaurants, etc).

For physical activity, the focus should be less on exercise's relationship to calories and more on how much exercise, what types, ability to perform, enjoyment and its relationship to positive mental health. Studies have shown that exercising for enjoyment rather than appearance is correlated with low self-objectification, low body dissatisfaction and less disordered eating.Reference Prichard and Tiggemann33 By focusing on exercise as something enjoyable and healthy, the focus will be less on exercise as a means to lose weight or look ‘better’, and thus improve overall mental health. Apps should also adapt to users’ personal contexts and needs around physical activity and healthy eating, as well as acknowledge systemic barriers and the role of trauma. Because customisation may be crucial for supporting users’ needs, more sensor-based and passive tracking are being explored.Reference Vu, Lin, Alshurafa and Xu34 However, caution must be exercised, as automated detection often reproduces biases and existing norms, exacerbating inequities, which can worsen mental health.

Other important aspects of health not easily captured in many current diet and fitness apps include positive body image, mental health and bodily functioning. For example, does a user feel good in their clothes? How is their self-esteem, emotion regulation, concentration, etc? Are they depressed, anxious, etc? Are they experiencing any pain or discomfort? Are they less tired throughout the day, and do they have improved sleep? All these things are important aspects of health. Even for users whose weight loss is a healthy goal, these factors may influence their needs and ability to lose weight, which means supporting these needs can positively affect all users.

Conception of appropriate usage: encouraging less logging (in some cases)

The quantified self movement coupled with our conception of appropriate app usage can lead to an obsession (about logging, food, weight and exercise) and the development of an app dependency, which is partly fuelled by how much and how often designers, developers and researchers think people should use these types of digital tools. To promote consistent and long-term use, many apps contain reminders to log and gamified aspects (e.g. streaks). This, coupled with the quantification, leads to users becoming obsessed with logging, which is in line with prior research.Reference Honary, Bell, Clinch, Wild and McNaney6,Reference Cordeiro, Epstein, Thomaz, Bales, Jagannathan and Abowd32 However, contrary to some research,Reference Cordeiro, Epstein, Thomaz, Bales, Jagannathan and Abowd32 users with eating disorder behaviours do not really ‘lose the habit’ of logging, because they feel the need to have control over their food and body. Despite numerous studies aiming to reduce app abandonment,Reference Cordeiro, Epstein, Thomaz, Bales, Jagannathan and Abowd32,Reference Lazar, Koehler, Tanenbaum and Nguyen35,Reference Epstein, Caraway, Johnston, Ping, Fogarty and Munson36 abandonment is not always negative. In fact, for users with eating disorder behaviours, taking a break from apps can be beneficial.Reference Eikey and Reddy7 Taking time off from apps can help users learn to listen to their body's signals of hunger and fullness and decrease their dependency on apps, which is important if we wish to promote health. Therefore, reducing logging reminders and encouraging breaks may be beneficial. Ways to reward users for engaging with apps without viewing quantified behaviours or actively logging (e.g. providing an alternative app view during break periods) could be explored.

Moreover, we need to ask ourselves: what role should these apps play in users’ lives? Are they meant to be used every day throughout a person's life or are there more finite periods? How do we determine a success versus a failure (and should we impose a viewpoint of ‘success’ or allow users to choose)? We have to stop pushing an ideal, universal use and start understanding how people actually use these technologies ‘in the wild’, and how their needs change over time. Then we can design around their natural patterns of use, be more adaptive and flexible, and acknowledge different situations and contexts. Although app vendors want users to use their technology long term, we also must understand that this is not appropriate for all users and may even be harmful for some.

Visual cues and feedback: investigating effects more thoroughly

Findings show that app visualisations and feedback, such as coloured visualisations and messages, can unintentionally contribute to unhealthy behaviours. Instead of promoting healthy behaviour change, red and green visualisations in combination with the focus on numbers often result in users feeling a high sense of achievement when being under their calorie budget and extreme negative emotions when being over their budget, which has been seen in other research.Reference Honary, Bell, Clinch, Wild and McNaney6 These colours were likely chosen because of the connotations they already have in some societal contexts. However, these effects in the context of diet and fitness apps are not well studied. Studying these effects is crucial, given that the effects of colour choice can vary from context to context.Reference Gnambs, Appel and Batinic37–Reference Singh39 Thus, we need to examine the effects of colours on users, and find ways to balance emotion response and behaviour change strategies.

The rewards and punishments users get from diet and fitness apps through these visualisations and the focus on the quantified self often promote excess competition. Although many apps want to encourage competition, users with eating disorder behaviours often develop unhealthy competitive behaviours. Not only do these visualisations instil a sense of reward in punishment in users, but they also tend to be very limited. For instance, at the time of this study, in MyFitnessPal, users see the red number regardless of whether they exceed their daily allotment by 1 or 1000 calories, which does not make sense if the focus of these apps is promoting health. Therefore, we need to develop more nuanced visualisations to motivate users without negatively affecting them.

Users also felt motivation from (what are intended to be) ‘negative’ messages and visual cues. For example, the ‘Complete Diary’ function in MyFitnessPal is meant to motivate users in the appropriate context and provide a warning to deter unhealthy habits. In many instances, users felt both messages motivated them to continue unhealthy behaviours regardless of the content, suggesting that more research is needed to understand how warnings and other feedback messages influence user perceptions and behaviours. One of the issues lies in the threshold that is used to determine with what feedback is presented. Although these algorithms are proprietary to MyFitnessPal, at the time of this study, MyFitnessPal seems to use a baseline of 1000 calories consumed to determine which message the app shows. If users do not hit this threshold, then they are shown the ‘Based on your total calories consumed for today, you are likely not eating enough’ message. If users consume over 1000 calories, then the app presents ‘If every day were like today, you would weigh X pounds in X weeks’ message. This occurs regardless of how many calories users have remaining. Thus, more research is needed to understand the appropriate thresholds to use to provide different feedback based on users’ needs.

Further, precautions such as warnings should not focus on taking away someone's agency or labelling someone or their behaviours as ‘bad.’ There is a tendency to do this with eating disorder-related behaviours, which can increase stigma and reinforce negative emotions. Rather than adding these types of features, users and potential users from a variety of backgrounds should be more meaningfully involved in all aspects of the design process in a way that honours their lived experiences as expertise, and have the power to inform design decisions within these apps.

Limitations

First, the sample comprised a small subset of rather homogenous users. Thus, it is likely that not all consequences and perceptions are represented in this work. Future research should include more users from a variety of races, ethnicities, cultures, genders, ages and types of conditions. Second, BMI has a number of problems and limitations. It was used in this study as way to provide additional information only, not to advocate for its blanket use to denote health or diagnose/treat eating disorders. Third, unfortunately, normative clinical data that have similar contexts and participants are not easily available for all measures. In general, the means reported in clinical samples for the EDE-Q 6.0 and CIA 3.0, (e.g. Dahlgren et alReference Dahlgren, Stedal and Rø40) are higher than the present study; however, it is important to note that participants in this study were often recollecting past experiences with eating disorder behaviours, and many reported being in recovery currently. Thus, it is possible that eating disorder symptom scores at the time of the study were lower than they would have been if the study had occurred during what participants described as the worst points of their eating disorders. The findings suggest that specific design choices are problematic for some users. However, these design features and choices themselves were not tested. Research could benefit from experimental testing of these designs, as well as participatory and community-driven design of diet and fitness apps.

In conclusion, the use of diet and fitness apps by women with eating disorder behaviours is likely more common than many realise, given the rates of dieting and weight loss among healthy weight and underweight women.Reference Yaemsiri, Slining and Agarwal41,Reference Fayet, Petocz and Samman42 This work identifies problematic aspects of design and design suggestions, as well as implications for clinicians and educators. Although this study focuses on users with a history of eating disorders, redesigning apps to focus on health is beneficial to all users. Ultimately, this research emphasises the need for a fundamental shift toward a more holistic, personalised approach to health and how it is represented in digital tools.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1011

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number DGE1255832. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank participants for sharing their experiences and expertise. This research would not be possible without them.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study may be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, E.V.E. Participant privacy and consent is of utmost importance. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declaration of interest

None

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.