Introduction and rationale

The language of population ageing is now embedded in national discourses about the wellbeing of societies and their members. In the Global North, drivers of population ageing such as low birth rates, increased longevity and improved survival of people with disabilities have been celebrated as evidence of effective public health strategies (Crosignani, Reference Crosignani2010; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014; Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Comas-Herrera and Jagger2018). Similarly, in an effort to value all lives, the United Nations has resolved to leave no one behind (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2011).

These celebratory conclusions about the positive outcomes of population ageing stand in stark contrast to those that long ago were branded as ‘apocalyptic demography’ (Robertson, Reference Robertson1997). Considerable alarm about the negative impact of population ageing still resonates in every sector from housing (Lund, Reference Lund2017) to income security (Grech, Reference Grech2018). Among these is widespread concern about a ‘crisis in care’ resulting from increased numbers of older people, with higher levels of disability and reduced funding to support them (Deusdad et al., Reference Deusdad, Pace and Anttonen2016; Jagger, Reference Jagger2017). Evidence is mounting of frail older people with unmet needs for support (Humphries et al., Reference Humphries, Thorlby, Holder, Hall and Charles2016) and who are at risk of social isolation and loneliness (Smith and Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2019).

Contexts of family care

In the midst of this framing of a care crisis, attention has turned again to families as central players in the solution. Tronto (Reference Tronto2017: 30) argues that the resurgence of families as the proper locus of care is an expected response from neoliberal societies that believe, ‘if people are now less well cared for, it must, by definition, be a failure of their own personal or familial responsibility’. In many countries efforts are under way to maximise family care capacity through policy levers and campaigns to prepare people to care (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2016), positioning adults as personally responsible for assuming the carer role and for the financial and social implications that flow from it. Analysts in the United Kingdom (UK) note inherent tensions between expectations to do more to support older relatives and pressures to stay longer in employment (Starr and Szebehely, Reference Starr and Szebehely2017). In their analysis of public policy across countries in Europe and Asia, Kodate and Timonen (Reference Kodate and Timonen2017: 301) see a variety of approaches to increasing, encouraging and necessitating family care inputs. Their common feature is the ‘stealthily growing role of family carers’.

Alongside policy settings that reflect a search for more family care is the demographic context that points to reduced family care capacity. The hallmarks of population ageing – lower birth rates and increased longevity – mean that families have fewer younger members to care for older generations (Redfoot et al., Reference Redfoot, Feinberg and Houser2013). Increased geographic mobility and high labour force engagement raise concerns about care gaps resulting from unavailability of family members who might otherwise be carers (Scharlach et al., Reference Scharlach, Gustavson and Dal Santo2007; Young and Grundy, Reference Young and Grundy2008). Family fluidity resulting from high divorce rates and diverse partnership arrangements results in diffuse care obligations (Fingerman et al., Reference Fingerman, Pillemer, Silverstein and Suitor2012; Connidis and Barnett, Reference Connidis and Barnett2019). One might conclude that while the policy context is one of ‘family care by stealth’, the demographic context is of ‘stealthily disappearing family carers’.

In the face of these macro policy discourses and demographic trends about care gaps, researchers have been creating evidence that families have not disappeared but are making substantial contributions to the lives of those with chronic health problems and disabilities (Hoff, Reference Hoff2015; Ankuda and Levine, Reference Ankuda and Levine2016). Yet also there is growing evidence of negative impact on their social connections, financial wellbeing and health (Bauer and Sousa-Poza, Reference Bauer and Sousa-Poza2016; Keating and Eales, Reference Keating and Eales2017).

It is within this setting of high levels of costs to carers and their substantial contributions that Starr and Szebehely (Reference Starr and Szebehely2017) remind us of the danger of thinking about families as the panacea for care gaps. The question is how to move beyond the apparent impasse of conflicting discourses about families as present or absent, with untapped care capacity or overwhelmed.

The goal of this paper is neither to advance the search for unused family care capacity nor to establish its futility but to create a more nuanced understanding of family care as a basis for challenging stealth discourses. In the study described in this paper, we present data from a national survey of family carers that illustrates diversity in care to a variety of family members across broad sweeps of the lifecourse.

Lifetimes of family care

The call for more research on family care may seem unwarranted given the extensive body of research on family care. We know a great deal about what family carers do (e.g. Cès et al., Reference Cès, De Almeida Mello, Macq, Declercq and Schmitz2017) and who they care for (e.g. Grossman and Webb, Reference Grossman and Webb2016). However, most studies to date are focused on a period of care to a specific care receiver such as a parent or a spouse; or by carers at a particular place in the lifecourse (e.g. young carers, mid-life carers, older carers). These snapshots of care do not account for the likelihood that, over a long sweep of time, a person may have multiple care experiences that build on one another.

Care trajectories and cumulative costs for family carers have been largely ignored, despite a small amount of evidence that family care can involve multiple episodes with diverse patterns and consequences across the lifecourse (Fast et al., Reference Fast, Dosman, Lero and Lucas2013; Lunsky et al., Reference Lunsky, Robinson, Blinkhorn and Ouellette-Kuntz2017). A better understanding of lifetime patterns of care would enhance our knowledge of family care experiences in important ways. Do young carers continue to care throughout their lives? Do those caring for parents subsequently care for spouses, older relatives or friends? Importantly, how might these patterns differ from each other in ways that influence carers’ ability or willingness to assume further care responsibilities? Addressing these questions can, in turn, inform our understanding of cumulative advantage and disadvantage (Carmichael and Ercolani, Reference Carmichael and Ercolani2016) in ways that make clear the deficiencies of relying on evidence about current episodes of care for research, policy or practice purposes.

Such an exploration seems timely given the families by stealth discourses. It seems timely as well given growing evidence that family care has become a normative part of the lifecourse. A national survey in Canada (Sinha, Reference Sinha2013) showed that, in a single year, 28 per cent of Canadians over age 15 had provided care to a family member or friend. But nearly half (46%) said they had provided care at some time in their lives. Estimates are even higher in the UK where 60 per cent are expected to be carers at some point in their lives (Carers UK, Reference Carers2015). In this paper we begin this exploration by reporting on the results of an empirical examination of lifecourses of family care of older Canadians.

Framing the research on lifecourses of family care

The conceptual framing of this research comes from Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019) who proposed a lifecourse domain of family care grounded in lifecourse assumptions that transitions and trajectories create the structure and rhythm of individual lives (Alwin, Reference Alwin2012; Elder and George, Reference Elder, George, Shanahan, Mortimer, Kirkpatrick Johnson and M2016). They conceptualise care as having components of both ‘doing tasks’ and ‘being in relationships’ that evolve over time. Family carers are distinguished by their close kin connections or long-standing friendships with the cared-for person. Family care trajectories, then, are patterns of moving into and out of episodes of care and the evolution of close relationships across time. They are bounded by bookends that mark the beginning and end of lifecourses of family care. Informed by these conceptual building blocks and empirical evidence, Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019) hypothesised three family care trajectories which they labelled generational, career and serial.

In the Methodology section of the paper we operationalise the proposed family care trajectory building blocks and create empirical lifecourse trajectories which we then compare to those that were hypothesised.

Methodology

Data

Statistics Canada's General Social Survey Cycle 26 on Caregiving and Care Receiving provided the opportunity to examine lifecourse patterns of care as it included retrospective data on care provided by family carers across the lifecourse and its consequences. In the survey, care was operationalised as having provided help to a family member or friend of any age with a long-term health condition, physical or mental disability, or with a problem related to ageing. Data collection occurred between March 2012 and January 2013 using random digit dialling and computer-assisted telephone interviewing. The overall response rate for the survey was 65.7 per cent, yielding a full sample of 23,093 respondents representative of the population of all individuals aged 15 and older living in the ten Canadian provinces (excluding residents of the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and institutionalised persons).

Sample

For this study, we selected a sub-sample of respondents aged 65+ who had ever provided care to a family member or friend. Respondents aged 65 and older were expected to have the most complete care histories (though it should be noted that some will engage in additional care episodes in the future). The final sample for this study comprised all respondents age 65 and older who had ever provided family care (N = 3,299). Taken to the population level, they represent 2.1 million Canadians over age 65, or half of all non-institutionalised older adults living in the ten Canadian provinces.

Operationalisation of variables

We follow the identification of Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019) of the key elements of trajectories as bookends that mark the start and end of a lifecourse of care; care episodes that are periods of care to an individual; and the sequencing of these care episodes across time. Based on these key elements, we operationalised four components of care trajectories: age of onset of the first care episode (representing the first bookend); number of episodes of care in the individual's lifecourse (to a maximum of sixFootnote 1); total duration of all episodes of care; and the extent to which episodes overlapped one another. These comprised the independent variables used in the Latent Profile Analysis (LPA).

Age at onset of the care trajectory is the age at which a respondent carer reported entering into their first episode of care. Responses ranged from age 4 to age 92. This variable was treated as continuous in the LPA. (The final bookend of the care trajectory could not be assessed as future engagement in care cannot be predicted.) Number of care episodes is a count of the number of times during their lifecourse that the respondent provided care to a family member or friend, to a maximum of six. Responses ranged from one to six and was treated as a count variable in the LPA. Total duration of care was the sum of the length of all care episodes reported, excluding overlapping years (i.e. times during which the respondent was caring for more than one person at the same time were counted only once). The total duration ranged from one to 64 years and was treated as a count variable in the LPA. Sequencing is represented by a count of total number of years in which respondents reported overlapping episodes of care. Years of overlap ranged from one to 57 and was treated as a count variable in the LPA.

In order to characterise the care trajectories further we also examined factors relevant to family care: carer sex; relationship between the carer and their care receiver; and age at start and end of each care episode. Sex was a dichotomous variable indicating whether the carer was male or female. Relationship to the care receiver for each care episode included the categories of spouse (including co-habiting partners and former spouses), child (including children-in-law), parent (including parents-in-law), sibling (including brothers and sisters-in-law), other kin or non-kin (including friends, neighbours and work colleagues) of the carer. For each care episode age at start and age at end of the episode was a continuous variable determined from respondents’ reports.

Analyses

To address our research questions, LPA and cross-tabulations were conducted. All analyses were weighted using survey weights provided by Statistics Canada to ensure that model parameter estimates represented the target population of persons in Canada over the age of 65 (excluding residents of the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, and institutionalised persons), who had ever provided care to a family member or friend.

Creating the care trajectories

We used LPA to identify care trajectories among our sample of carers aged 65 and older based on the four core variables: age at first transition into care, number of care episodes, duration of care and years of overlap (operationalised above). LPA is one of several person-centred statistical approaches to mixture modelling that categorises individuals into substantively meaningful, homogeneous sub-groups based on patterns of association among independent variables (Nylund et al., Reference Nylund, Asparouhov and Muthén2007; Dyer and Day, Reference Dyer and Day2015). LPA is appropriate when analyses are conducted with either continuous or a mix of continuous and discrete variables (Galovan and Schramm, Reference Galovan and Schramm2017; Galovan et al., Reference Galovan, Drouin and McDaniel2018). LPA is also useful for this study because it allows us to assign respondents to a particular care trajectory type based on the estimated probability of membership in that group. This can then be used in analyses to describe further the characteristics of each care trajectory.

LPA is superior to other mixture modelling techniques in capturing complex patterns among multiple characteristics, relying as it does on more objective and rigorous fit indices and other criteria to uncover distinctive sub-groups of people (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Kellermanns and Zellweger2017). For this study, the LPA was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation and multiple fit indices (Bayesian Information Criterion, sample-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion, Akaike Information Criterion, Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test) and entropy (Nylund et al., Reference Nylund, Asparouhov and Muthén2007).

Describing care trajectories

We cross-tabulated each of the five care trajectory profiles with the four core characteristics entered into the LPA along with additional characteristics important in understanding patterns of care: relationship between carers and care receivers, age of entry into and exit from each episode, and sex of carer.

Findings

In this section of the paper we report findings from the LPA and detailed descriptions of the five trajectory types identified by the LPA.

Creating care trajectory profiles

LPA analyses allowed us to determine whether groups of family carers with similar lifecourse patterns of care, based on four care trajectory components, could be detected and how many distinct patterns of care could be identified.

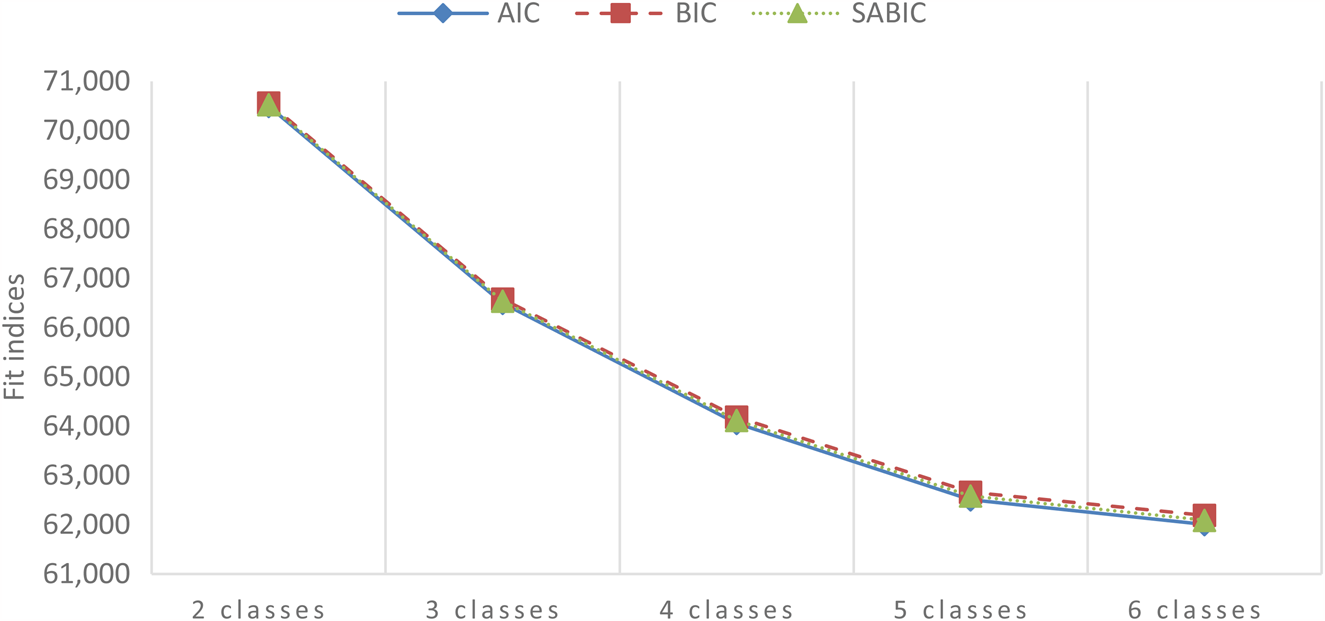

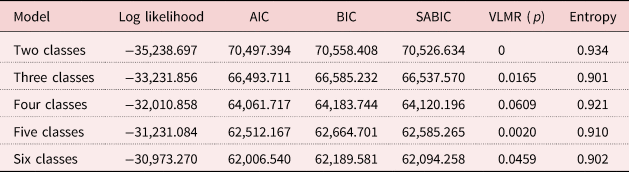

Table 1 shows the fit indices for the latent class models with two to six classes. Model fit indices and substantive interpretation indicated that a five-class solution best fit the data. Overall, these classes were well differentiated as evidenced by entropy values greater than 0.9. Figure 1 illustrates the fit indices for the models graphically. The slope can be seen to drop sharply between the two- and three-class, and the three- and four-class models and flatten between the four- and five-class models. Although the six-class solution does improve model fit, the gain is small and results in a class that applies to only 2.8 per cent of the sample, conditions that Dyer and Day (Reference Dyer and Day2015) advise should be treated with caution. The five-class model also better matches the theoretical assumptions about lifecourse care trajectories, and the theorised trajectory types (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019), while creating a more nuanced understanding of lifecourse diversity.

Figure 1. Results of Latent Profile Analysis.

Notes: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion. BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion. SABIC: sample-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion.

Table 1. Fit indices for latent profile class models

Notes: N = 3,299. AIC: Akaike Information Criterion. BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion. SABIC: sample-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion. VLMR: Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test.

Describing care trajectories

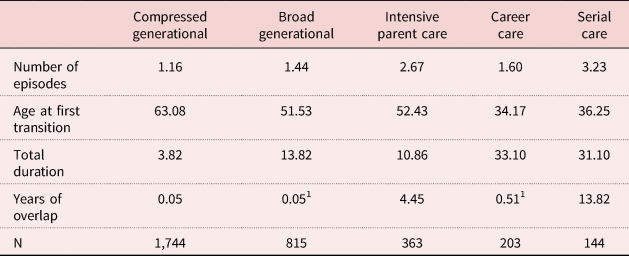

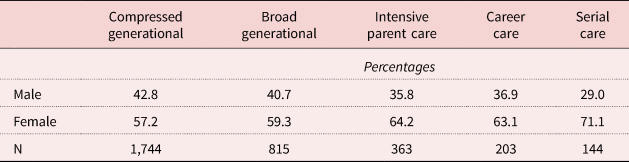

Each of the five care trajectories that emerged from the LPA is distinguished by its unique cluster of characteristics. Based on our examination of all of these characteristics we labelled the five care trajectories: compressed generational, broad generational, intensive parent care, career, and serial. Each is described below based on core care trajectory components (Table 2), sex (Table 3), age of entry into and exit from each care episode (Table 4), and carer–care receiver relationship for each episode (Table 5).

Table 2. Weighted means of core characteristics by care trajectory type

Notes: N = 3,299. 1. Use with caution.

Table 3. Sex distribution by care trajectory type

Note: N = 3,299.

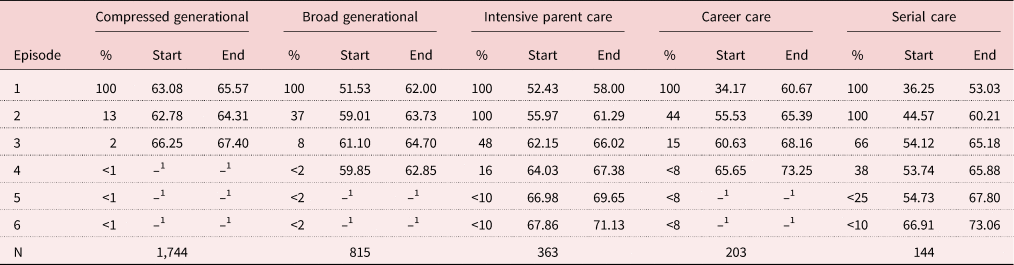

Table 4. Episode characteristics by care trajectory type

Notes: N = 3,299. 1. Too unreliable to be published.

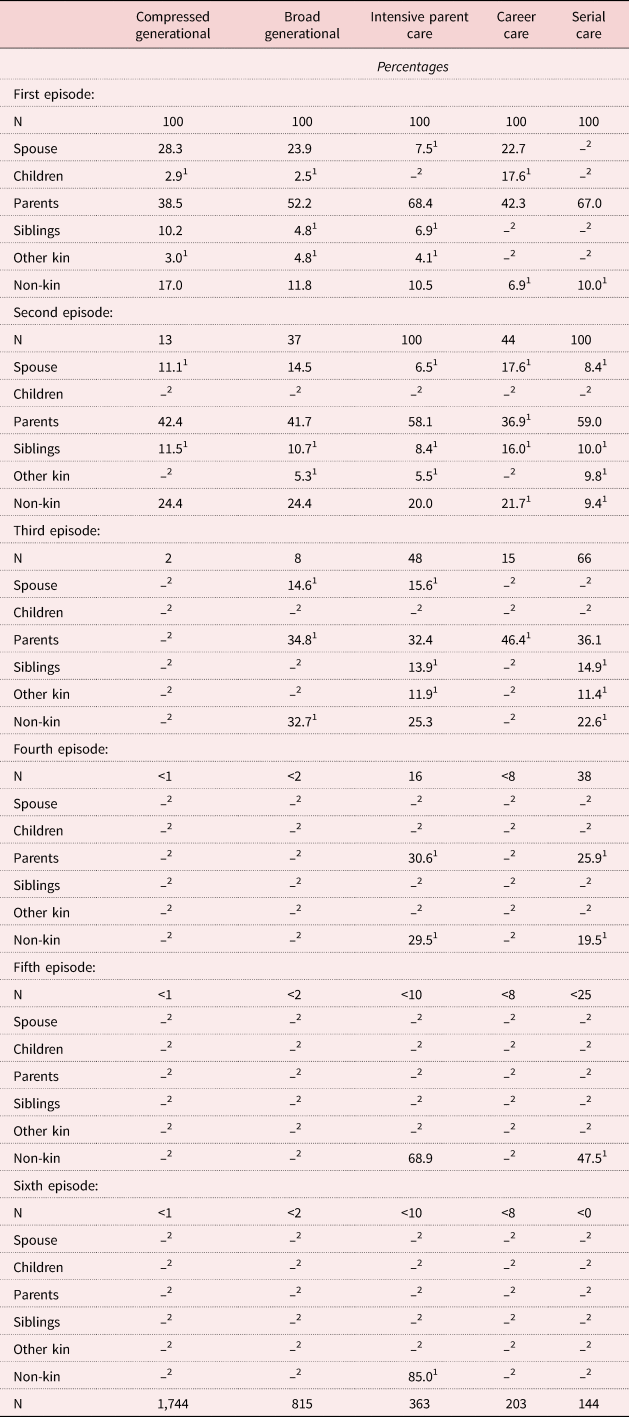

Table 5. Relationship between carer and care receiver for each care episode by care trajectory

Notes: 1. Use with caution. 2. Too unreliable to be published.

Compressed generational trajectory

The compressed generational trajectory is the most common (N = 1,744; 54%). Compared to the other trajectories, it had the oldest average age of onset (63.1 years), the smallest number of episodes (1.16), shortest total duration (3.8 years on average) and almost no overlap among care episodes (0.05 years). Just over half of carers in this trajectory were women (57.2%). There is little evidence of sequencing for this trajectory type as only 13 per cent of carers reported a second care episode. For those who did, subsequent care episodes occurred within a compressed time-frame, following shortly on the first care episode. Most cared for close kin (spouses or parents). Overall, the defining feature of the compressed generational trajectory is a single, short period of care in later life within high-obligation older or same-generation close kinship ties.

Broad generational trajectory

The broad generational trajectory is the second most common (N = 815; 25%). It is characterised by mid-life onset (51.5 years on average) and an average of 1.4 care episodes with a total average duration of 13.8 years. The first care episode was relatively long (10 years on average). More than one-third of carers (37%) reported a second, shorter episode in their late fifties to early sixties, while 8 per cent reported a third. However, there was almost no overlap among episodes (0.05 years on average). Nearly 60 per cent of carers in this trajectory were women (59.3%). Most cared for close kin of same or older generations (parents or spouses), especially in the first episode. Later care episodes increasingly involved non-kin. Defining features of the broad generational trajectory are a first long episode of care in mid-life followed by shorter episodes, increasingly to same-generation close friends, neighbours and other non-kin. The broad generational trajectory highlights the fact that care goes beyond close kin relationships.

Intensive parent care trajectory

The intensive parent care trajectory comprises a smaller proportion of the study sample (N = 363; 11%). It is characterised by mid-life onset (average 52.4 years) and an average of 2.7 care episodes with a total average duration of 10.9 years. There were nearly 5 years of overlap among care episodes (average 4.5 years). More than 60 per cent of carers in this trajectory were women (64.2%). All carers in this trajectory type had two care episodes, almost half (48%) had a third and a smaller proportion had a fourth episode (data are suppressed for some later episodes because of small cell sizes). Sequencing of these care episodes reflected periods of overlap as well as short gaps across a moderately long period. Care to parents dominated these episodes with little generational sequencing. The defining feature of the intensive parent care trajectory is a decade or more in mid-life of providing care to parents (in-law), often caring for more than one parent at the same time.

Career care trajectory

The career care trajectory is relatively uncommon with only 6 per cent (N = 203) of carers fitting this profile. Compared to the other trajectories, it had the youngest average age of onset (34.2 years) and longest total duration (average 33.1 years). It had 1.6 care episodes on average with little overlap among them (0.5 years on average). More than 60 per cent of carers in this trajectory were women (63%). All carers fitting this trajectory type had one very long care episode spanning more than 25 years on average; in their mid-fifties 44 per cent of these carers had a second care episode and 15 per cent had a third. These later episodes were much shorter on average and overlapped for a relatively brief time near the end of the first care episode. Care to high-obligation, close kin dominated the first lengthy care episode. It is the only trajectory in which care to children with long-term health conditions/disability was evident (17.6%). The defining feature of the career care trajectory is a very long first episode of care to a high-obligation, close family member starting at a relatively early age and spanning more than two decades.

Serial care trajectory

The serial care trajectory was the least common trajectory type (N = 144; 4%). It had a relatively early average age of onset (36.2 years), the most episodes (average 3.2), long duration (average 31.1 years) and the greatest amount of overlap among care episodes (13.8 years on average). It had the largest proportion of women carers (71.1%) of all trajectory types. All carers in this trajectory reported two care episodes, two-thirds reported a third episode (66%), with smaller percentages having a fourth, fifth and sixth episode (data are suppressed for some later episodes because of small cell sizes). The first two care episodes spanned more than 15 years each on average. Although most cared for parents in the first episode, care to siblings, more distant kin and non-kin became more prevalent in subsequent episodes. The defining feature of the serial care trajectory is a lifelong pattern of caring for others (close kin, distant kin and non-kin), often at the same time, that begins in the mid-thirties and spans more than three decades.

Summary

Findings show that care for family members and friends is not a one-off experience. Most of the care trajectories involved transitions into and out of multiple care episodes spanning broad sweeps of the lifecourse. Findings also indicate that carers can be grouped in meaningful ways and confirm the utility of the four components of care trajectories comprising the independent variables used in the LPA. They also illustrate variability in the ways in which care plays out across the lifecourse. The implications of these findings are explored in the next section of the paper.

Discussion and implications

Our findings create increased understanding of both patterns of care across the broad sweep of a lifecourse and of diversity in these patterns. The five care trajectories bear similarities to those hypothesised by Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019) but also illustrate some of the complexities of lifecourses of family care not previously theorised. Fundamentally, they illustrate how much more we learn about care by considering lifecourses, not snapshots, of family care.

Three of five trajectories identified in this study resemble generational care trajectories (GCT) as hypothesised by Keating et al. (2019: 152) as ‘episodes of care within high obligation close-kin relationships with generational sequencing to cared-for persons’.

Care to parents was first identified as a normative pattern more than 30 years ago (Brody, Reference Brody1985). The identification of an intensive parent care trajectory both reflects and extends our understanding of this normative pattern. It reflects the hypothesised GCT in its finding of episodes of care within older-generation close-kin relationships. There is little generational sequencing, although sequencing is evident across multiple, overlapping episodes of care to parents. Knowledge of the existence of such an intensive pattern may be useful as we think about pressures on older workers who are managing employment and parent care or those trying to re-enter employment after withdrawing to provide parent care.

The large volume of research on spouse care suggests that it is the most likely same-generation care experience, especially for women. We did not find a distinct trajectory reflecting spousal care. However, we see two patterns illustrating different configurations of older and same-generation care. The compressed generational pattern reflects expected older or same-generation care relationships. Rather than provided in sequence, the compressed generational pattern comprises predominantly single care episodes to either a parent or spouse. However, given that the sample for this study includes carers as young as 65, it seems likely that some will have subsequent care episodes that may approximate the expected generational sequencing.

The broad generational pattern includes more than one episode of care, also to older or same-generation recipients. However, this generational pattern diverges from the hypothesised GCT by virtue of having a wider set of care relationships to same-generation kin and non-kin, especially in second and third care episodes.

The hypothesised career trajectory was defined as ‘a single episode of care of long duration within a high-obligation close-kin relationship’ (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019: 153). Rather than based in normative expectations about care to close kin, it was drawn from evidence of one of the successful drivers of population ageing, that more people both survive and live longer with disabilities. Thus, this trajectory was hypothesised to comprise a continuous and lengthy episode of care, likely to a child needing lifelong support. Our findings did indeed include a career trajectory distinguished by carers starting at an early age and caring for more than three decades. Care to children was reflected among these lengthy care relationships, but so too was parent and spouse care, a reminder that chronic conditions, mental health challenges and traumatic injuries also may require long periods of care.

Career carers are distinguished by starting young and caring long. In contrast, generational patterns span much shorter periods of time at an entirely different stage of the lifecourse. Importantly, career trajectories do not end with this first long episode. At about the same age that generational carers are transitioning into their first episode of care, nearly half of career carers are beginning a second care episode as they enter their third decade of providing care.

Finally, the serial care trajectory was defined as ‘multiple episodes of care to diverse care receivers with no normative or predictable sequencing’ (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019: 154). Our findings also show a serial pattern distinguished by numerous care episodes, extensive overlap and long duration. Yet early episodes are predominantly normative parent care. It is only in the third care episode that we see increased evidence of care for those with whom they have loose ties. There are indications that this pattern continues into fourth and subsequent episodes. However, these data cannot be reported because of small cell size.

Data limitations and opportunities

Secondary analyses inevitably come with limitations. Trajectories were created based on data on episodes of care across the lifecourse collected retrospectively. The limits of recall data are well documented (Kjellsson et al., Reference Kjellsson, Clark and Gerdtham2014). So, for example, memory of early care provision may be incomplete while more onerous or longer-term episodes may be recalled more readily.

In addition, respondents were able to report a maximum of six episodes of care, an operational decision intended to minimise respondent burden and maximise survey response rates. Most (84%) of our sample reported fewer than six episodes, suggesting that truncation may be a minor problem. However, those who did report six episodes may actually have experienced even more than they could report; others may have additional contributions as they move further along their lifecourse.

We also cannot tell when a lifecourse of care is complete. This is less an issue of data adequacy than of lifecourses continuing to unfold. It does mean, however, that we must be vigilant against inadvertently rendering invisible late-life contributions to care by virtue of constraining the number of care episodes and failing to track care provision in very late life and thereby contributing to the discourse of older people being primarily receivers rather than providers of care.

Advancing theory

The framing of family care as a lifecourse domain has been useful in several ways. Perhaps most importantly, it incorporates the assumption that time matters. The five trajectories that emerged from our analyses provide the basis for further understanding how time and events unfold in a variety of ways across lifecourses of care. We sense an intensity in parent care due to the multiple and overlapping care responsibilities across a single decade of life. Career care feels quite different, intense because of the relentlessness of a single long episode of care, sometimes to children with long-term disabilities, with additional short periods of care taken on in mid-life, but collectively spanning more than three decades. These findings beg such questions as, does care to fewer recipients that takes up most of the adult lifecourse result in more or less cumulative disadvantage than more episodes packed into a much shorter time?

The place in the lifecourse where trajectories are focused also may make a difference. Compressed, broad and parent care trajectories all occur at a lifecourse stage when we might reasonably expect to take on care responsibilities, primarily when carers are in their fifties and sixties. Might it be that a decade of parent care is experienced differently and perhaps is more readily integrated because it is expected, than career care which begins at a time when we expect to be focused on raising children and building careers and which has the potential to interfere with carers’ other lifecourse transitions. In turn, how can the normative timing of parent care be reconciled with the employment lifecourse phase when full engagement in paid work is the norm? It is time to pay attention to how care plays out over the lifecourse, its intersections with employment and family lifecourse domains (Fast et al., Reference Fast, Dosman, Lero and Lucas2013), and what diverse care pathways may mean for carers’ quality-of-life relationships.

Time matters in terms of the evolution of relationships as well. In this study we were unable to provide evidence of the unfolding of what Dannefer et al. (Reference Dannefer, Stein, Siders and Patterson2008: 105) have called the ‘complex relational nature of care’. How do carers in an intensive parent care trajectory navigate relationships with their siblings while caring in turn for more than one parent? Do children of career carers spend their childhood in the shadow of a demanding care relationship? Over time, might serial carers actually gain social network members as they develop social connections to the networks of the different people they care for? Do broad generational carers become isolated, especially if the persons they care for have dementia? These questions remain unexamined and yet are vitally important to our understanding of whether carers are embedded in convoys of care or are navigating the care lifecourse alone. The challenge is to set aside notions of families as always available (or unavailable) to support one another and to create evidence of the ways in which family relationships are solidified or torn apart by cumulative care experiences.

Moving forward

Research

A strong case has been made for attending to full lifecourses rather than snapshots of short segments of them, as is typically the case. We have been able to demonstrate that the structure of care does evolve across the lifecourse and that it evolves in different ways for different individuals. This highlights the limitations of a knowledge base founded on single care episodes. While this study is a good start, it signals rich research opportunities going forward.

We have contributed new knowledge about patterns of care across lifecourses, but care trajectories need further explication. We have captured some of the characteristics of care episodes and their sequencing, specifically periods of concurrent care provision to more than one recipient at the same time. But sequencing also implies patterns in the gaps between care episodes, which we did not examine in this study. In what ways do the gaps between episodes (e.g. their length and timing) further illuminate how patterns of care play out over time? Do carers with long gaps between care episodes revert to their previous lifestyles or are their lifecourses permanently set on a new path?

Our finding that care trajectories also are gendered extends evidence about gender diversity in the provision of family care, challenging beliefs that family care is inevitably the purview of women. Substantial differences in proportions of men carers across profiles suggest the need to understand better what might be gendered expectations about involvement over long periods of time, or to particular relatives or at some stages of the lifecycle. Given that these patterns reflect people who are now aged 65 and older, it will be useful to track differences for future cohorts of carers.

Policy discourses and directions

Evidence of diverse lifecourse pathways of family care provides a basis for addressing the discourses of ‘families by stealth’ and ‘stealthily disappearing families’. For more than a decade academics and policy think tanks have been advocating a lifecourse approach to policy making (Policy Research Initiative, 2004; Bovenberg, Reference Bovenberg2008). However, if families by stealth is in fact a policy goal to bolster beleaguered health and social care systems, the lack of uptake of such approaches is not surprising. As McDaniel and Bernard (Reference McDaniel and Bernard2011: S2) point out, a lifecourse approach to policy making ‘can make visible policy options and interventions previously hidden’. Yet, a lifecourse approach to policy development is hardly radical. Social policy is often made to mitigate the impact of risks arising from lifecourse transitions and events on subsequent life chances. For example, policy levers across the employment lifecourse are well developed. There are strategies to enhance labour force engagement of young people, parental leaves to assist new parents and increases in age of pension eligibility to retain older workers.

A policy lens on lifecourses of family care could similarly mitigate risks to carers. The term prudent health and social care (Welsh Government, 2017) is one reflection of a policy aspiration to contain costs while delivering good care. It seems timely then to develop a family care strategy that would support those very people meant to bolster the formal care system. Evidence presented here of variations in lifecourse patterns of care can provide a policy road map to shape these interventions. For example, existing employment policy might well be used as a basis to assist career carers to enter or remain in the labour force early in their care journeys, and equally to protect intensive parent carers from labour force exit with few opportunities to return.

In conclusion, we believe that the evidence presented here of lifecourse trajectories of family care provides a foundation for understanding better patterns of care work across the lifecourse and the gendered nature of care provision. We have much to learn about how these patterns might be associated with risks of poor outcomes for carers, an important next step in determining the sustainability of the family care sector. Further exploration of how care relationships evolve in the context of this care work is essential to deconstructing notions of family care as available but underexploited versus those of families disappearing in the demographic transitions that are the hallmarks of population ageing.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Dr Adam Galovan for his assistance with Latent Profile Analysis.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed substantially to the creation of this paper.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Kule Institute of Advanced Study (UOFAB KIASRCG Keating, Health, Wealth and Happiness: Dynamics of Families and a Good Old Age?, 2016–2019); AGE-WELL NCE, Canada's Technology and Aging Network (NCEAGEWELL AW CRP2015WP2.4, Assistive Technology that Cares for the Caregiver, 2015–2020); the Economic and Social Research Council (award number ES/P009255/1, Sustainable Care: Connecting People and Systems, 2017–2021, Principle Investigator Sue Yeandle, University of Sheffield). Financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.