More than half of the general population experiences a traumatic event in their lifetime, with the most common being accidents and injuries, unexpected death of a loved one, witnessing someone seriously injured or killed and being the victim of a crime. Approximately 6.8% of people will ultimately develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Kessler Reference Kessler, Aguilar-Gaxiola and Alonso2017), which can be a debilitating condition characterised by avoidance, intrusive memories, hyperarousal and negative alterations in mood and cognition. Established treatment options include psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, with newer interventions expanding options for the future.

Diagnosis

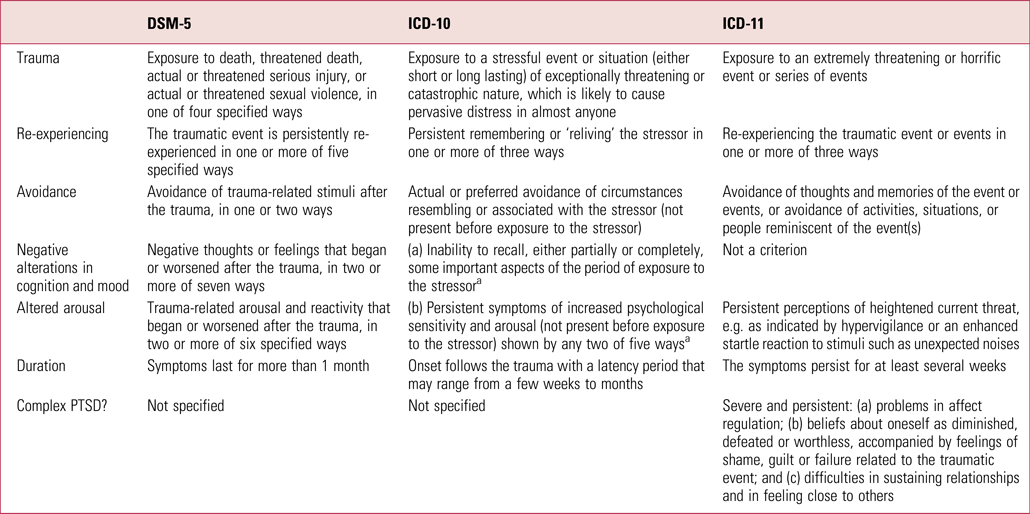

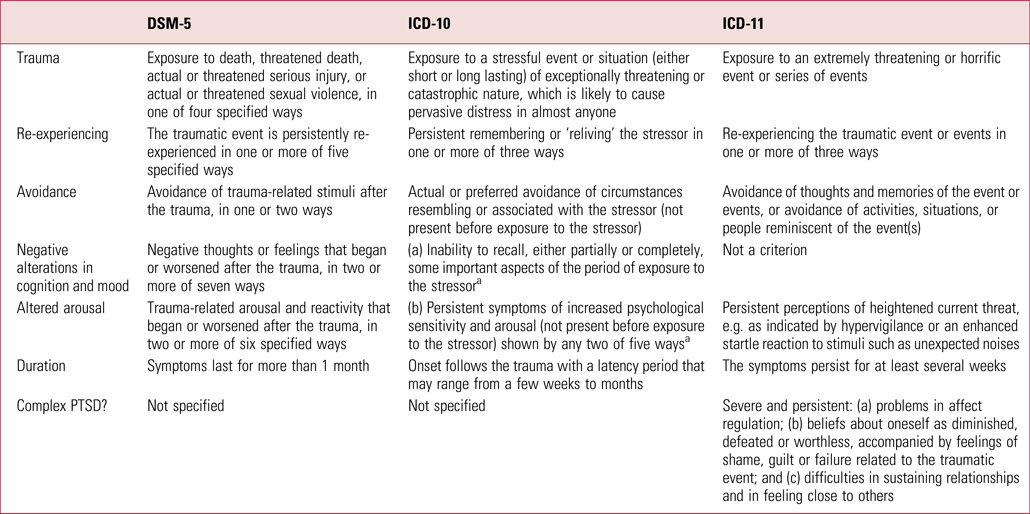

Diagnostic criteria for PTSD vary between DSM-5, ICD-10 and ICD-11, but all three require one or more exposures to extremely threatening or horrific events (Table 1). DSM-5 requires a minimum six symptoms from four clusters (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and altered arousal), whereas ICD-10 requires four symptoms from three clusters. A significant difference between ICD-10 and DSM-5 is the incorporation of ‘negative alterations in cognition and mood’ into the DSM criteria. ICD-11 requires three symptoms, including re-experiencing, avoidance and persistent perception of heightened threat. Multiple studies have shown that, in general, individuals evaluated for PTSD under criteria prior to ICD-11 have fewer overall PTSD diagnoses (Brewin Reference Brewin, Cloitre and Hyland2017).

TABLE 1 Comparison of diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

a ICD-10 requires either (a) or (b).

Sources: DSM-5: https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/. ICD-10: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/bluebook.pdf. ICD-11: https://icd.who.int/en.

Included in ICD-11 is a new diagnosis, complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Complex PTSD is generally applied to individuals with multiple severe prolonged traumas. In addition to the usual PTSD diagnostic criteria, complex PTSD includes the criteria of (a) problems in affect regulation, (b) distorted beliefs of self, including shame, (c) guilt or worthlessness, and (d) difficulty sustaining relationships. Complex PTSD is not fully understood, and more research is needed to identify the extent of comorbidity, develop diagnostic assessment instruments, and articulate the extent to which modified or alternative treatments are needed.

Another emerging concept in diagnosis and treatment of PTSD is moral injury. Refined through the study of deployed military personnel exposed to traumatic events, moral injury is defined as perpetrating, failing to prevent or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs. Moral injury has been associated with more severe PTSD symptoms, higher rates of comorbid depression, diminished functioning, greater likelihood of suicidality and poorer response to psychotherapy (Griffin Reference Griffin, Purcell and Burkman2019). Moral injury in healthcare workers has emerged as a concern during the COVID-19 outbreak owing to the shift to crisis standards of care, with personnel working under extreme stress with limited resources and faced with unprecedented triage decisions. It remains unclear whether the presence of moral injury necessitates alternative treatments.

Broadly, risk for PTSD is the result of a complex interplay between pre-event, event and post-event factors (Brewin Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine2000). Predisposing factors include low socioeconomic status, limited social support, female gender and genetics. Event characteristics that increase risk include intentional acts of violence, physical injury, death of a loved one, moral injury and psychological identification (i.e. thoughts such as ‘That could be me or my loved one’). Diminished social connections, job loss and relationship difficulties have all been associated with elevated risk of developing PTSD and other disorders following exposure to trauma. Although no single factor predicts PTSD, an understanding of the extent of risk for an individual or community affected by trauma assists in estimating risk and effectively targeting interventions.

Treatment

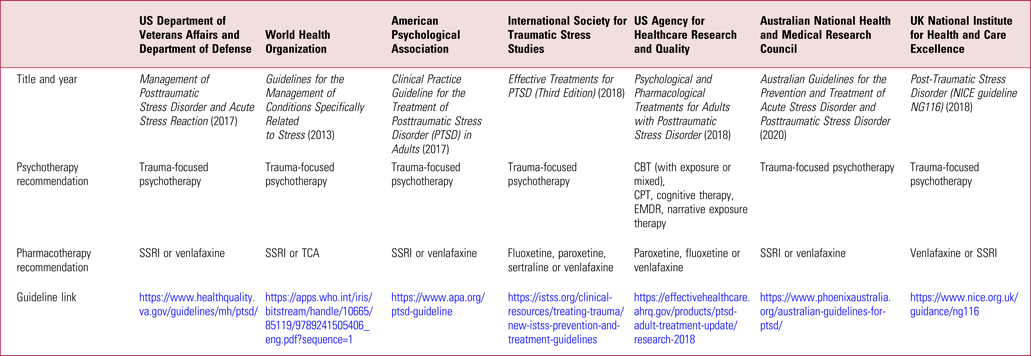

Current evidence-based treatment options for PTSD focus on psychotherapy, with a small selection of pharmacotherapies (Table 2). Patient adherence to medications is a frequent problem, often as a result of side-effects, patient perceptions or limited clinical benefit. Psychotherapies are generally considered more effective but require an extended time commitment and may result in exacerbations of symptoms long before improvement occurs. As a result, maintaining patient engagement in treatment is important for improving prognosis. Newer and more novel treatments are needed to augment the limited options currently available.

TABLE 2 Treatment guideline recommendations for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CPT, cognitive processing therapy; EMDR, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

The majority of treatment guidelines recommend trauma-focused psychotherapy as a first-line treatment for PTSD, with the strongest body of evidence for cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure therapy. Eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing and narrative exposure therapy also have evidence of efficacy. Common components of trauma-focused psychotherapies include imagined re-exposure to the event and exposure to real-life triggering cues typically avoided. The common goals of trauma-focused therapies are to promote re-exposure to avoided memories, process emotional responses and correct cognitive distortions.

Pharmacotherapy is recommended as second-line therapy or as first-line therapy for those unwilling to engage in psychotherapy. Selective serotonin and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs) are recommended, with paroxetine, fluoxetine and venlafaxine having the most robust evidence, although medications may offer only limited benefit to certain populations (Lee Reference Lee, Schnitzlein and Wolf2016). Prazosin is commonly used to treat nightmares, although there is equivocal efficacy evidence. Treatment for sleep disruption should be an important early target of interventions because improved sleep often reduces irritability and improves concentration, allowing patients to more effectively participate in treatment. Atypical antipsychotics should be used with caution, given their lack of evidence and broad side-effect profile. Trazodone is frequently used clinically, with anecdotal success, for PTSD-related sleep problems and has an excellent safety profile but there is virtually no scientific evidence supporting such use. Benzodiazepines are consistently not recommended for the treatment of PTSD, with some evidence suggesting worse outcomes. Medications used to augment SSRIs include valproate, risperidone, topiramate, pregabalin and mirtazapine, all showing limited or no benefit. Recent augmentation trials with glutamatergic agents, such as riluzole and memantine, have demonstrated limited benefit.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) options have increasingly been explored, although their measured impact on PTSD symptoms appears to be limited (Benedek Reference Benedek and Wynn2016). Mindfulness-based interventions and yoga offer some benefit in stress reduction, although generalisability of results is often limited owing to the various types of mindfulness and yoga used in different studies. Acupuncture appears to be helpful in stress reduction and is commonly offered as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD with anecdotal success, but with a limited evidence base. Other modalities are available, and a few are even undergoing formal study, but there is limited evidence supporting CAM options, particularly as first-line treatment. Despite the limited evidence, these modalities are often very safe, well-tolerated and increasingly preferred by patients, so their inclusion in a broader treatment plan can be a sensible clinical choice.

Potential systems being explored for the treatment of PTSD include the endocannabinoid system, glutamatergic pathways, the renin–angiotensin system, kappa opioid receptors and the orexin/hypocretin pathway. In addition to these, research is underway with various psychedelic compounds, such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and psilocybin.

Conclusions

PTSD is a common and debilitating mental disorder. Prevention efforts to reduce exposure to traumatic events and early detection and identification of those at highest risk following exposure to trauma are ideal. Technology is beginning to enhance our understanding of genetic factors and biomarkers to more effectively target interventions. Although psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy options exist, they have limitations in their efficacy and tolerability, creating a strong need for newer and novel therapeutic interventions.

Author contributions

J.C.M. made substantial contributions to the conception and design, drafting and revisions, and final approval of this work and is accountable for all aspects of the work. G.H.W. and J.C.W. made substantial contributions to the concept, design, drafting and revisions of this manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense, the Uniformed Services University, the Department of Health and Human Services or the United States Public Health Service.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.